Abstract

Background

European regional variation in cancer survival was reported in the EUROCARE-4 study for patients diagnosed in 1995–1999. Relative survival (RS) estimates are here updated for patients diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus, stomach, and small intestine from 2000 to 2007. Trends in RS from 1999–2001 to 2005–2007 are presented to monitor and discuss improvements in patient survival in Europe.

Materials and Methods

EUROCARE-5 data from 29 countries (87 cancer registries) were used to investigate 1-and 5-year RS. Using registry-specific life-tables stratified by age, gender, and calendar year, age-standardised ‘complete analysis’ RS estimates by country and region were calculated for Northern, Southern, Eastern and Central Europe, and for Ireland and United Kingdom (UK). Survival trends of patients in periods 1999–2001, 2002–2004, and 2005–2007 were investigated using the ‘period’ RS approach. We computed the 5-year RS conditional on surviving the first year (5-year conditional survival), as the ratio of age-standardised 5-year RS to 1-year RS.

Results

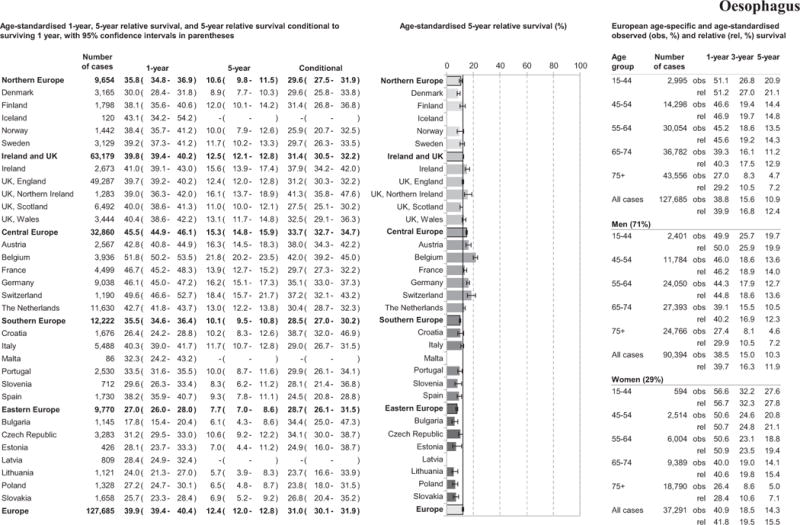

Oesophageal cancer 1- and 5-year RS (40% and 12%, respectively) remained poor in Europe. Patient survival was worst in Eastern (8%), Northern (11%), and Southern Europe (10%). Europe-wide, there was a 3% improvement in oesophageal cancer 5-year survival by 2005–2007, with Ireland and the UK (3%), and Central Europe (4%) showing large improvements.

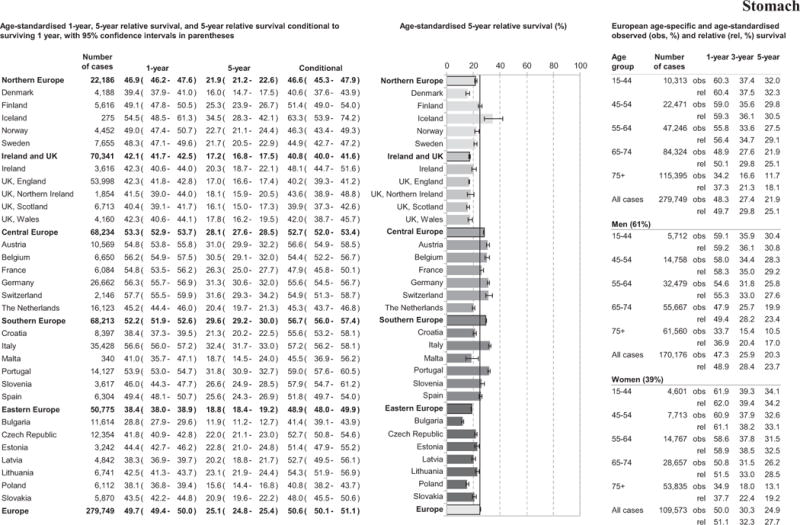

Europe-wide, stomach cancer 5-year RS was 25%. Ireland and UK (17%) and Eastern Europe (19%) had the poorest 5-year patient survival. Southern Europe had the best 5-year survival (30%), though only showing an improvement of 2% by 2005–2007.

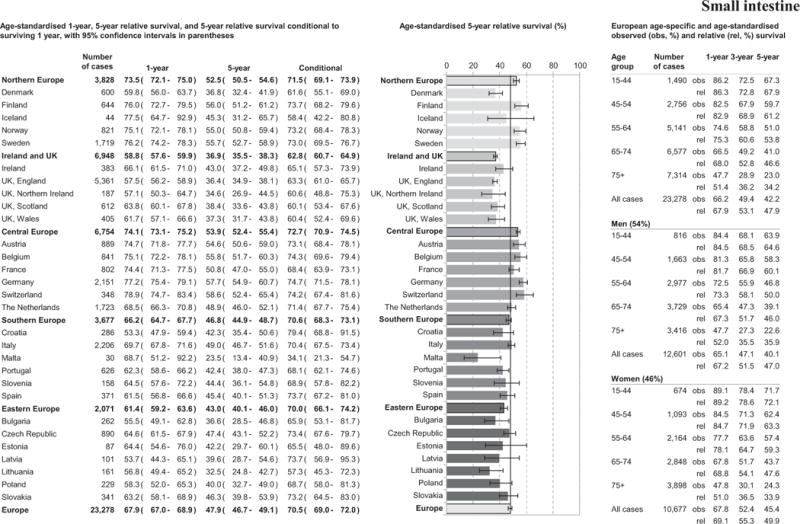

Small intestine cancer 5-year RS for Europe was 48%, with Central Europe having the best (54%), and Ireland and UK the poorest (37%). Five-year patient survival improvement for Europe was 8% by 2005–2007, with Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe showing the greatest increases (≥9%).

Conclusions

Survival for these cancer sites, particularly oesophageal cancer, remains poor in Europe with wide variation. Further investigation into the wide variation, including analysis by histology and anatomical sub-site, will yield insight to better monitor and explain the improvements in survival observed over time.

Keywords: oesophageal, stomach, small intestine, survival, Europe

Introduction

This article focuses on European relative survival (RS) estimates and trends for oesophageal, stomach and small intestine cancer patients, diagnosed up to 2007, with follow-up to December 31st 2008, as part of EUROCARE-5. Regional variation in RS estimates throughout Europe has been consistently reported for cancer patients, including upper gastrointestinal tract cancers, diagnosed in 1990–1994 [1], 1995–1999 [2] and 1999–2007 [3].

Oesophageal cancer ranks as the eighth most common cancer worldwide with approximately 5 cases per 100,000 diagnosed in Europe annually [4]. Two main histological subtypes, adenocarcinoma (OAC) and squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), display regional variation in incidence across Europe [5]. Stomach cancer is the third most common cause of cancer death globally [6]. Wide variation in stomach cancer incidence across Europe has been reported with recent declines in most European countries as a result of lifestyle changes, Helicobacter pylori detection and cancer treatment. Incidence of non-cardia tumors is high in Southern Europe [7] which, correspondingly, has the best 5-year patient survival [3]. While the small intestine comprises 90% of the length of the bowel, small intestine cancers are rare with an age-standardised incidence rate of 2 per 100,000 person-years in the USA [8] with lower incidence rates reported within Europe [9]. Small intestine cancers exhibit a diverse histology with adenocarcinomas, carcinoid (now classified as neuroendocrine), lymphomas and sarcomas most common [10]. Incidence of small intestine cancers, particularly neuroendocrine malignancies, have increased in the USA [11,12] and Sweden [13], likely as a result of improved detection and classification. Neuroendocrine small intestine cancers are the most common histological subtype and confer superior prognosis compared to other small intestine entities [12]. Incidence of epithelial small intestine cancers is reportedly highest in Northern and lowest in Eastern Europe [14]; possibly due to geographic differences in diagnostic testing and variable capture by cancer registries.

Methods

Methods used for the analysis of EUROCARE-5 data are described in a dedicated paper in this EJC issue [15]. Briefly, survival data were obtained from 29 countries, 21 with 100% national coverage, from 87 cancer registries. Countries were grouped into Northern, Central, Southern and Eastern Europe and Ireland and UK.

All patients diagnosed with a primary and malignant oesophageal, stomach or small intestine cancer, as identified by topography codes C15, C16 (cardia C16.0 and non-cardia C16.1–C16.6) and C17, respectively, of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3), diagnosed from 2000–2007 were included. Patients with morphology codes 9590-9989 (ICD-O-3), or who were diagnosed by death certificate only (DCO), autopsy only, or censored with null survival time, were excluded. Patients were not excluded if they had a previous primary tumour. All the registries with less than 13% of DCO (for all cancers combined) were included in the analysis.

One-year RS, 5-year RS and 5-year RS conditional on surviving the first year after diagnosis (5-year conditional) were estimated using the ‘complete’ cohort approach for patients diagnosed 2000–2007 (with follow-up to 2008) stratified by gender and age-group (i.e. 15–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75 years or older) as previously described [15]. Age standardised survival [16] and European average estimates [15] are also provided. Survival trends were estimated for countries with cases diagnosed between 1999 and 2007 (n=24 countries) with follow-up to 2008, using the ‘period’ approach [17] to reliably predict 5-year survival in the years, 1999–2001, 2002–2004, and 2005–2007.

Results

Oesophageal, stomach and small intestine cancers were more common in men than women, Table 1. Some countries in Eastern Europe had a high percentage of DCO cases. Elsewhere in Europe the highest DCO rates were reported in Germany. Mean age at diagnosis for oesophageal, stomach and small intestine cancers ranged from 60.7–71.6, 66.8–73.1 and 60.5–68.9 years, respectively, Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of cases, percentage Death Certificate Only (DCO) cases and mean age at diagnosis (years) for oesophageal, stomach and small intestine cancers by country/region before exclusion of autopsy and DCO cases.

| Oesophagus | Stomach | Small Intestine | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | Men | Women | % DCOa | Mean age | All cases | Men | Women | % DCOa | Mean age | All cases | Men | Women | % DCOa | Mean age | |

| Northern EU | |||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 3,177 | 2,242 | 935 | 0 | 68.2 | 4,200 | 2,700 | 1,500 | 0 | 68.7 | 602 | 303 | 299 | 0 | 66.7 |

| Finland | 1,859 | 1,218 | 641 | 1.1 | 69.2 | 5,812 | 3,213 | 2,599 | 0.7 | 70.1 | 691 | 367 | 324 | 1.4 | 65.3 |

| Iceland | 121 | 87 | 34 | 0 | 71.6 | 281 | 171 | 110 | 0 | 72.5 | 47 | 27 | 20 | 0 | 66.2 |

| Norway | 1,466 | 1,041 | 425 | 0.8 | 70.1 | 4,521 | 2,717 | 1,804 | 0.6 | 72.5 | 836 | 441 | 395 | 0.2 | 66.9 |

| Sweden | 3,203 | 2,300 | 903 | 0 | 70.1 | 7,863 | 4,740 | 3,123 | 0 | 72.1 | 1,819 | 1,012 | 807 | 0 | 68.9 |

| Ireland and UK | |||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 2,706 | 1,707 | 999 | 0.8 | 69.7 | 3,701 | 2,297 | 1,404 | 1.6 | 69.8 | 392 | 228 | 164 | 1.5 | 65.3 |

| UK-England | 50,610 | 32,299 | 18,311 | 2.6 | 71.5 | 55,973 | 36,023 | 19,950 | 3.5 | 72.9 | 5,501 | 2,985 | 2,516 | 2.5 | 68.1 |

| UK-Northern | |||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 1,294 | 817 | 477 | 0.7 | 69.9 | 1,882 | 1,129 | 753 | 1.3 | 71.5 | 189 | 109 | 80 | 1.1 | 65.7 |

| UK-Scotland | 6,531 | 4,072 | 2,459 | 0.4 | 70.7 | 6,771 | 4,096 | 2,675 | 0.5 | 72.0 | 615 | 313 | 302 | 0.2 | 67.5 |

| UK-Wales | 3,530 | 2,196 | 1,334 | 2.4 | 71.2 | 4,324 | 2,706 | 1,618 | 3.8 | 73.1 | 413 | 210 | 203 | 1.9 | 68.2 |

| Central EU | |||||||||||||||

| Austria | 2,569 | 2,066 | 503 | 0 | 64.7 | 10,572 | 5,817 | 4,755 | 0 | 71.1 | 889 | 463 | 426 | 0 | 66.2 |

| Belgiumb | 3,984 | 3,054 | 930 | 0 | 66.3 | 6,737 | 4,146 | 2,591 | 0 | 71.6 | 856 | 457 | 399 | 0 | 66.6 |

| Franceb | 4,531 | 3,817 | 714 | 0 | 65.9 | 6,194 | 3,961 | 2,233 | 0 | 71.3 | 822 | 462 | 360 | 0 | 66.8 |

| Germanyb | 10,152 | 8,021 | 2,131 | 10.6 | 65.3 | 31,664 | 17,865 | 13,799 | 15.6 | 70.9 | 2,357 | 1,254 | 1,103 | 8.2 | 66.4 |

| Switzerlandb | 1,222 | 936 | 286 | 1.0 | 68.0 | 2,223 | 1,317 | 906 | 1.7 | 70.3 | 381 | 213 | 168 | 0 | 68.1 |

| The Netherlands | 11,654 | 8,355 | 3,299 | 0 | 67.6 | 16,208 | 10,268 | 5,940 | 0 | 69.9 | 1,769 | 920 | 849 | 0 | 66.0 |

| Southern EU | |||||||||||||||

| Croatia | 1,815 | 1,492 | 323 | 7.6 | 64.9 | 9,146 | 5,553 | 3,593 | 8.2 | 68.6 | 306 | 173 | 133 | 6.5 | 66.1 |

| Italyb | 5,600 | 4,178 | 1,422 | 1.5 | 68.9 | 36,113 | 20,960 | 15,153 | 1.6 | 72.6 | 2,248 | 1,259 | 989 | 1.2 | 68.6 |

| Malta | 94 | 69 | 25 | 8.5 | 68.2 | 359 | 216 | 143 | 5.0 | 70.0 | 31 | 13 | 18 | 3.2 | 60.5 |

| Portugalb | 2,619 | 2,201 | 418 | 0.1 | 63.7 | 14,723 | 8,931 | 5,792 | 0.1 | 67.2 | 641 | 366 | 275 | 0 | 66.3 |

| Slovenia | 739 | 607 | 132 | 2.3 | 64.9 | 3,772 | 2,314 | 1,458 | 2.4 | 68.9 | 162 | 95 | 67 | 0 | 65.1 |

| Spainb | 1,782 | 1,541 | 241 | 2.6 | 65.1 | 6,598 | 4,193 | 2,405 | 3.6 | 70.4 | 378 | 225 | 153 | 1.3 | 67.2 |

| Eastern EU | |||||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | 1,478 | 1,152 | 326 | 22.5 | 64.6 | 14,616 | 9,005 | 5,611 | 20.5 | 68.2 | 345 | 197 | 148 | 24.1 | 63.5 |

| Czech Republic | 3,680 | 3,090 | 590 | 5.1 | 63.6 | 13,760 | 7,996 | 5,764 | 4.6 | 69.3 | 1,019 | 559 | 460 | 3.9 | 65.4 |

| Estonia | 434 | 355 | 79 | 0 | 64.9 | 3,277 | 1,776 | 1,501 | 0.2 | 66.8 | 90 | 36 | 54 | 0 | 64.2 |

| Latvia | 881 | 739 | 142 | 6.5 | 63.8 | 5,324 | 2,948 | 2,376 | 6.6 | 67.0 | 114 | 52 | 62 | 11.4 | 65.8 |

| Lithuania | 1,180 | 1,022 | 158 | 4.8 | 63.1 | 7,047 | 4,095 | 2,952 | 4.2 | 67.2 | 176 | 83 | 93 | 8.5 | 65.8 |

| Polandb | 1,353 | 1,070 | 283 | 1.7 | 63.5 | 6,253 | 3,938 | 2,315 | 1.6 | 67.0 | 230 | 122 | 108 | 0 | 64.3 |

| Slovakia | 1,937 | 1,732 | 205 | 12.5 | 60.7 | 6,826 | 4,111 | 2,715 | 12.3 | 6\8.1 | 397 | 212 | 185 | 10.8 | 64.3 |

Also includes ‘autopsy-only’ basis of diagnosis.

Pooled rates as these countries did not have national coverage.

Oesophageal cancer

European average 1-year age-standardised RS was 39.9%, with 12.4% of patients surviving 5-years, Figure 1. Patients in the Central Europe region, particularly Belgium, had the best survival in Europe while survival was poorest in Eastern Europe. Lithuania and Bulgaria had the lowest 5-year RS estimates. Conditional 5-year survival displayed less heterogeneity across Europe, Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Age-specific and age-standardised relative survival for adult oesophageal cancers diagnosed in 2000–2007, by European region, country, gender, and overall.

Survival, at all follow-up time points investigated, decreased with increasing age, Figure 1. One-, 3- and 5-year age-standardised RS was higher in women than men across all follow-up time points, Figure 1.

Overall oesophageal cancer 5-year age-standardised patient survival improved from 9.9% to 12.6% between 1999–2001 and 2005–2007. Graphs of 5-year RS by region and Europe overall are presented in Supplement 1. The largest regional improvements in 5-year RS were observed in Ireland and UK and Central Europe with limited improvements observed in Eastern or Southern Europe, (Table 2 and Supplement 1). Similar improvements in patient survival were noted between 1999–2001 and 2002–2004, and between 2002–2004 and 2005–2007 for most regions.

Table 2.

Five-year relative survival (RS) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of oesophageal cancer in three periods (1999–2001, 2002–2004, 2005–2007) by country, European region and European average, with p-values of differencesa between periods.

| Number of cases analysed across all time periods | 1999–2001 | 2002–2004 | 2005–2007 | 2005–2007 vs 1999–2001 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | Abs diff | p-value | |||

| Europe | 111006 | 9.9 | (9.3–10.5) | 11.7 | (11.0–12.3) | 12.6 | (12.0–13.2) | 2.7 | <0.001 | |

| Northern EU | 10471 | 9.1 | (8.0–10.4) | 11.3 | (10.1–12.8) | 10.8 | (9.7–12.1) | 1.7 | 0.023 | |

| Denmark | 3401 | 4.6 | (3.3–6.4) | 9.0 | (7.0–11.5) | 9.7 | (7.9–11.8) | 5.1 | <0.001 | |

| Finland | 1959 | 9.6 | (7.2–12.7) | 12.9 | (9.9–16.7) | 12.1 | (9.5–15.2) | 2.5 | 0.108 | |

| Icelandb | 129 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Norway | 1572 | 8.4 | (5.7–12.4) | 12.5 | (9.5–16.5) | 10.9 | (8.0–14.8) | 2.5 | 0.150 | |

| Sweden | 3411 | 13.3 | (11.0–16.0) | 12.3 | (10.0–15.2) | 10.6 | (8.8–12.8) | 2.7 | 0.052 | |

| Ireland and UK | 67862 | 10.3 | (9.8–10.8) | 11.9 | (11.4–12.4) | 13.5 | (13.0–14.1) | 3.2 | <0.001 | |

| Ireland | 2816 | 11.9 | (9.6–14.7) | 15.3 | (12.7–18.3) | 16.7 | (14.2–19.6) | 4.8 | 0.005 | |

| England | 52786 | 9.9 | (9.4–10.6) | 11.5 | (10.9–12.1) | 13.7 | (13.1–14.3) | 3.7 | <0.001 | |

| Northern Irelandb | 1389 | 9.6 | (7.1–13.0) | 14.6 | (11.3–18.7) | – | – | – | – | |

| Scotland | 7142 | 10.0 | (8.6–11.6) | 11.7 | (10.1–13.5) | 11.1 | (9.7–12.7) | 1.1 | 0.157 | |

| Wales | 3727 | 14.1 | (11.7–17.1) | 13.8 | (11.6–16.4) | 12.6 | (10.5–15.0) | 1.6 | 0.188 | |

| Central EU | 18139 | 10.8 | (9.9–11.8) | 13.9 | (12.8–15.0) | 15.2 | (14.2–16.2) | 4.3 | <0.001 | |

| Austria | 2711 | 11.7 | (9.4–14.6) | 17.9 | (15.1–21.2) | 17.1 | (14.6–20.0) | 5.4 | 0.002 | |

| France | 3365 | 13.0 | (11.2–15.0) | 11.2 | (9.6–13.0) | – | – | – | – | |

| Germanyb | 1804 | 16.1 | (12.8–20.4) | 13.7 | (10.6–17.7) | – | – | – | – | |

| Switzerland | 1075 | 15.3 | (11.4–20.5) | 18.3 | (14.3–23.4) | 18.9 | (14.6–24.4) | 3.6 | 0.145 | |

| The Netherlands | 11744 | 9.6 | (8.6–10.8) | 13.1 | (11.9–14.5) | 14.4 | (13.3–15.7) | 4.8 | <0.001 | |

| Southern EU | 4474 | 9.7 | (8.2–11.6) | 10.6 | (9.0–12.5) | 10.9 | (9.2–12.7) | 1.1 | 0.186 | |

| Italy | 3278 | 10.7 | (8.8–13.2) | 12.4 | (10.3–14.8) | 11.0 | (9.1–13.3) | 0.3 | 0.432 | |

| Maltab | 67 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Sloveniab | 805 | 7.1 | (4.2–12.1) | – | – | 8.6 | (5.5–13.6) | 1.5 | 0.289 | |

| Spain | 1792 | 7.9 | (6.1–10.2) | 7.9 | (6.1–10.2) | – | – | – | – | |

| Eastern EU | 10063 | 7.3 | (6.1–8.6) | 7.4 | (6.3–8.6) | 8.1 | (7.0–9.3) | 0.8 | 0.175 | |

| Bulgariab | 1172 | – | – | – | – | 6.7 | (4.2–10.7) | – | – | |

| Czech Republic | 3496 | 7.3 | (5.4–9.8) | 9.2 | (7.0–12.2) | 11.4 | (9.5–13.7) | 4.2 | 0.003 | |

| Estoniab | 485 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lithuaniab | 1348 | 8.4 | (5.6–12.5) | 4.7 | (2.9–7.5) | – | – | – | – | |

| Polandb | 1474 | 8.1 | (5.3–12.4) | 7.7 | (5.3–11.3) | 6.2 | (4.0–9.7) | 1.9 | 0.205 | |

| Slovakiab | 111006 | 6.4 | (3.9–10.3) | 10.1 | (6.4–15.6) | – | – | – | – | |

Abs = absolute, Diff = Difference.

Survival differences between periods have been assessed by the Z-test.

Standardized Survival rates could not be calculated where one or more age specific rates are absent due to small number of cases.

Note: % difference is the relative difference.

Note: Empty fields of RS in France and Spain in 2007 are due to a limitation of analysis to periods 1999–2001 and 2002–2004 only.

Stomach Cancer

One-year age-standardised RS for stomach cancer patients reached almost 50% with substantial regional variation, see Figure 2. While the Eastern Europe region had the poorest 1-year RS (38.4%), the 5-year RS was lowest in Ireland and UK (17.2%) region, with similar survival across all UK countries. Southern Europe had the best 5-year patient survival (29.6%) in Europe. While Eastern Europe had low 1- and 5-year RS, 5-year conditional survival was better than in Northern Europe, and Ireland and UK. Wide variation among countries was identified in 5-year RS estimates from 11.9% in Bulgaria to 34.5% in Iceland. Survival, at all follow-up time points investigated, decreased with increasing age, and women appeared to fare better than men.

Figure 2.

Age-specific and age-standardised relative survival for adult stomach cancers diagnosed in 2000–2007, by European region, country, gender, and overall.

Overall 5-year patient survival increased absolutely by less than 2% points across Europe between 1999–2001 and 2005–2007 (Table 3 and Supplement 2). The most marked improvement in patient survival was in Slovenia from 1999–2001 (RS 20.8%) to 2002–2004 (RS 27.1%), Table 3. Although no change was observed in 5-year RS in Northern Europe, improved patient survival was evident in Denmark and Sweden with a decrease in 5-year RS observed in Finland. The Netherlands had low RS compared to the rest of Central Europe across all periods.

Table 3.

Five-year relative survival (RS) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of stomach cancer in three periods (1999–2001, 2002–2004, 2005–2007) by country, European region and European average, with p-values of differencesa between periods.

| Number of cases analysed across all time periods | 1999–2001 | 2002–2004 | 2005–2007 | 2005–2007 vs 1999–2001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | Abs diff | p-value | ||

| Europe | 232452 | 23.3 | (22.9–23.8) | 23.8 | (23.4–24.3) | 25.1 | (24.6–25.6) | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Northern EU | 26201 | 22.4 | (21.4–23.5) | 21.7 | (20.7–22.7) | 22.7 | (21.6–23.8) | 0.3 | 0.360 |

| Denmark | 4691 | 14.0 | (12.2–16.2) | 14.7 | (12.7–16.9) | 18.3 | (16.3–20.6) | 4.3 | 0.002 |

| Finland | 6667 | 28.5 | (26.5–30.8) | 25.0 | (23.0–27.1) | 25.2 | (23.1–27.5) | −3.3 | 0.016 |

| Iceland b | 341 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Norway | 5341 | 23.5 | (21.2–26.1) | 21.8 | (19.6–24.3) | 23.5 | (21.1–26.2) | 0.0 | 0.499 |

| Sweden | 9152 | 21.4 | (19.8–23.2) | 22.6 | (20.8–24.5) | 22.5 | (20.7–24.4) | 1.0 | 0.214 |

| Ireland and UK | 83908 | 16.1 | (15.6–16.7) | 16.5 | (16.0–17.1) | 18.2 | (17.6–18.8) | 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Ireland | 4056 | 19.4 | (17.1–22.0) | 19.4 | (17.0–22.0) | 21.9 | (19.4–24.6) | 2.5 | 0.086 |

| England | 64533 | 16.1 | (15.5–16.7) | 16.3 | (15.7–16.9) | 18.0 | (17.3–18.7) | 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Northern Ireland | 2189 | 17.7 | (14.7–21.4) | 18.8 | (15.8–22.4) | 18.4 | (15.0–22.5) | 0.6 | 0.400 |

| Scotland | 7992 | 14.7 | (13.1–16.5) | 16.8 | (15.1–18.7) | 16.3 | (14.5–18.3) | 1.6 | 0.104 |

| Wales | 5144 | 16.1 | (13.9–18.6) | 16.5 | (14.3–18.9) | 20.0 | (17.5–22.9) | 4.0 | 0.015 |

| Central EU | 39365 | 24.0 | (23.2–24.9) | 24.7 | (23.9–25.6) | 26.2 | (25.3–27.1) | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Austria | 12740 | 30.7 | (29.1–32.3) | 29.8 | (28.2–31.5) | 33.6 | (31.8–35.4) | 2.9 | 0.009 |

| France b | 4997 | 25.4 | (23.4–27.5) | 28.1 | (26.1–30.3) | – | – | – | – |

| Germany | 4486 | 27.2 | (24.7–30.0) | 27.0 | (24.5–29.7) | 27.5 | (24.9–30.3) | 0.3 | 0.439 |

| Switzerland | 2019 | 25.0 | (21.6–29.0) | 29.3 | (25.5–33.7) | 31.4 | (27.4–36.0) | 6.4 | 0.014 |

| The Netherlands | 18808 | 18.9 | (17.8–20.1) | 20.6 | (19.4–21.8) | 21.1 | (19.9–22.3) | 2.2 | 0.005 |

| Southern EU | 29234 | 30.5 | (29.4–31.6) | 30.4 | (29.4–31.5) | 32.1 | (31.0–33.3) | 1.6 | 0.021 |

| Italy pool | 23784 | 32.7 | (31.5–34.0) | 31.6 | (30.4–32.9) | 33.8 | (32.5–35.1) | 1.1 | 0.126 |

| Malta b | 398 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Slovenia | 4116 | 20.8 | (18.5–23.5) | 27.1 | (24.4–30.1) | 27.9 | (25.3–30.7) | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Spain | 6569 | 25.1 | (23.5–26.8) | 25.9 | (24.2–27.7) | – | – | – | |

| Eastern EU | 53747 | 17.6 | (16.9–18.2) | 19.0 | (18.3–19.6) | 18.8 | (18. 2–19.5) | 1.3 | 0.004 |

| Bulgaria | 12555 | 10.9 | (9.8–12.1) | 12.5 | (11.3–13.8) | 12.8 | (11.7–14.0) | 2.0 | 0.010 |

| Czech Republic | 14449 | 18.1 | (16.9–19.4) | 21.3 | (19.9–22.7) | 22.6 | (21.2–24.0) | 4.4 | <0.001 |

| Estonia | 3852 | 21.8 | (19.3–24.7) | 24.8 | (22.0–27.8) | 22.2 | (19.6–25.1) | 0.3 | 0.432 |

| Lithuania | 8614 | 22.0 | (20.4–23.8) | 23.4 | (21.7–25.2) | 23.7 | (21.7–25.8) | 1.7 | 0.112 |

| Poland | 7164 | 15.2 | (13.5–17.0) | 16.7 | (15.0–28.5) | 15.6 | (14.0–17.4) | 0.4 | 0.367 |

| Slovakia | 7186 | 21.2 | (19.3–23.2) | 20.3 | (18.6–22.3) | 21.1 | (19.2–23.1) | −0.1 | 0.471 |

Abs = absolute, Diff = Difference.

Survival differences between periods have been assessed by the Z-test.

Standardized Survival rates could not be calculated where one or more age specific rates are absent due to small number of cases.

Note: % difference is the relative difference.

Note: Empty fields of RS in Spain in 2007 are due to a limitation of analysis to periods 1999–2001 and 2002–2004 only.

Southern and Central Europe had better patient survival for cardia and non-cardia cancers than other regions, Table 4. Survival for non-cardia cancer patients was significantly higher than for cardia cancer patients, Table 4. In Eastern Europe, as in Southern and Central Europe, patients with non-cardia cancer predominated, Table 4.

Table 4.

Age-standardised 1-year, 5-year relative survival, and 5-year relative survival conditional on surviving 1 year, with 95% confidence intervals, for cardia and non-cardia stomach cancers.

| Cardia | Non-cardia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| No. of cases | 1-year | 5-year | Conditional | No. of cases | 1-year | 5-year | Conditional | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | |||

| Europe | 48611 | 46.0 | 45.5–46.4 | 16.0 | 15.5–16.4 | 34.0 | 33.2–34.9 | 96020 | 54.6 | 54.3–54.9 | 30.5 | 30.1–30.9 | 66.3 | 65.9–66.8 |

| Northern EU | 5299 | 43.3 | 41.9–44.7 | 14.1 | 12.9–15.3 | 32.5 | 30.0–35.1 | 6027 | 55.2 | 53.8–56.5 | 28.6 | 27.1–30.2 | 51.9 | 49.4–54.5 |

| Denmark | 1687 | 41.0 | 38.6–43.4 | 12.8 | 10.8–15.0 | 31.2 | 26.8–36.2 | 1149 | 48.0 | 44.9–51.0 | 25.9 | 22.8–29.2 | 53.9 | 48.4–60.1 |

| Finland | 936 | 45.9 | 42.5–49.2 | 16.0 | 13.2–19.1 | 34.9 | 29.5–41.4 | 272 | 57.8 | 51.3–63.7 | – | – | – | – |

| Iceland | 41 | 31.0 | 18.0–44.8 | 10.3 | 3.4–19.1 | 33.2 | 15.2–72.5 | 70 | 74.7 | 62.7–83.0 | – | – | – | – |

| Norway | 967 | 43.9 | 40.6–47.1 | 15.4 | 12.7–18.5 | 35.2 | 29.6–42.0 | 1831 | 58.0 | 55.4–60.5 | 30.0 | 27.2–32.9 | 51.8 | 47.7–56.2 |

| Sweden | 1668 | 44.2 | 41.7–46.6 | 13.6 | 11.6–15.7 | 30.7 | 26.6–35.5 | 2705 | 55.9 | 53.7–58.0 | 28.0 | 25.6–30.4 | 50.1 | 46.3–54.1 |

| Ireland and UK | 19244 | 46.6 | 45.8–47.3 | 14.4 | 13.8–15.1 | 31.0 | 29.7–32.4 | 17457 | 48.4 | 47.5–49.3 | 23.2 | 22.3–24.0 | 47.9 | 46.3–49.5 |

| Ireland | 986 | 42.2 | 39.0–45.3 | 17.0 | 14.1–20.0 | 40.2 | 34.3–47.1 | 1705 | 46.2 | 43.8–48.7 | 24.4 | 21.9–27.0 | 52.8 | 48.3–57.7 |

| England | 14510 | 47.4 | 46.5–48.2 | 14.8 | 14.1–15.5 | 31.2 | 29.8–32.70 | 11932 | 49.2 | 48.1–50.3 | 23.1 | 22.0–24.2 | 46.9 | 45.1–48.9 |

| Northern Ireland | 462 | 46.4 | 41.6–51.1 | 16.2 | 12.3–20.7 | 35.0 | 27.5–44.5 | 534 | 42.2 | 37.4–47.0 | 21.2 | 16.9–25.8 | 50.1 | 41.9–59.9 |

| Scotland | 1983 | 42.9 | 40.5–45.3 | 11.3 | 9.6–13.2 | 26.4 | 22.7–30.7 | 1787 | 47.6 | 44.9–50.2 | 23.4 | 20.8–26.1 | 49.2 | 44.6–54.4 |

| Wales | 1303 | 46.7 | 43.8–49.6 | 13.2 | 10.9–15.8 | 28.4 | 23.8–33.8 | 1499 | 47.3 | 44.2–50.4 | 22.3 | 19.4–25.4 | 47.2 | 41.9–53.1 |

| Central EU | 13230 | 49.2 | 48.4–50.1 | 18.2 | 17.4–19.0 | 37.0 | 35.4–38.5 | 26709 | 60.9 | 60.3–61.5 | 36.0 | 35.2–36.7 | 59.1 | 58.0–60.1 |

| Austria | 1297 | 50.5 | 47.7–53.3 | 22.6 | 19.8–25.5 | 44.7 | 39.9–50.1 | 1895 | 65.9 | 63.5–68.1 | 40.2 | 37.3–43.1 | 61.0 | 57.3–65.0 |

| Belgium | 1264 | 55.9 | 53.1–58.7 | 20.5 | 17.7–23.5 | 36.7 | 32.1–41.9 | 1504 | 63.0 | 60.3–65.7 | 35.6 | 32.3–38.8 | 56.4 | 52.0–61.2 |

| France | 1384 | 50.6 | 47.9–53.3 | 14.7 | 12.6–17.0 | 29.0 | 25.3–33.4 | 2949 | 58.6 | 56.6–60.6 | 32.8 | 30.6–35.0 | 56.0 | 52.9–59.2 |

| Germany | 4506 | 52.7 | 51.2–54.2 | 22.3 | 20.7–23.9 | 42.3 | 39.7–45.1 | 11906 | 64.4 | 63.5–65.3 | 40.1 | 39.0–41.3 | 62.3 | 60.8–63.9 |

| Switzerland | 494 | 52.0 | 47.4–56.5 | – | – | – | – | 1145 | 64.1 | 61.1–67.0 | 40.8 | 37.2–44.3 | 63.6 | 59.1–68.4 |

| The Netherlands | 4285 | 42.4 | 40.9–43.9 | 13.1 | 11.9–14.5 | 31.0 | 28.3–34.0 | 7310 | 53.7 | 52.5–54.9 | 28.9 | 27.5–30.2 | 53.8 | 51.6–56.0 |

| Croatia | 476 | 42.43 | 37.7–47.1 | 27.0 | 21.9–32.4 | 63.7 | 54.2–74.9 | 446 | 56.6 | 51.6–61.4 | 37.4 | 31.4–43.5 | 66.1 | 57.6–75.8 |

| Southern EU | 5793 | 48.6 | 47.2–49.9 | 20.2 | 18.9–21.5 | 41.5 | 39.2–44.0 | 24960 | 60.1 | 59.4–60.7 | 36.2 | 35.5–36.9 | 60.2 | 59.2–61.3 |

| Italy | 3193 | 52.2 | 50.3–54.0 | 20.9 | 19.1–22.7 | 40.0 | 37.0–43.3 | 15728 | 61.3 | 60.5–62.1 | 37.1 | 36.2–38.1 | 60.6 | 59.2–61.9 |

| Malta | 65 | 35.9 | 25.5–46.4 | – | – | – | – | 107 | 49.2 | 38.8–58.7 | 25.4 | 16.9–34.8 | 51.7 | 38.6–69.3 |

| Portugal | 890 | 45.5 | 42.0–48.9 | 20.6 | 17.6–23.9 | 45.4 | 39.7–51.9 | 4188 | 59.4 | 57.8–60.9 | 36.1 | 34.4–37.9 | 60.8 | 58.4–63.4 |

| Slovenia | 473 | 46.2 | 41.4–50.8 | 18.3 | 14.1–22.9 | 39.6 | 31.8–49.3 | 1424 | 61.2 | 58.6–63.8 | 41.0 | 37.8–44.2 | 67.0 | 62.8–71.5 |

| Spain | 696 | 44.7 | 40.8–48.5 | 16.9 | 13.9–20.2 | 37.9 | 32.0–44.8 | 3067 | 55.4 | 53.5–57.2 | 30.8 | 28.9–32.7 | 55.6 | 52.7–58.5 |

| Eastern EU | 5045 | 36.4 | 35.1–37.8 | 13.1 | 12.0–14.4 | 36.1 | 33.2–39.2 | 20867 | 45.6 | 44.9–46.3 | 23.7 | 23.0–24.4 | 52.0 | 50.6–53.4 |

| Bulgaria | 1273 | 25.3 | 22.9–27.8 | 7.6 | 5.8–9.9 | 30.2 | 23.5–38.7 | 6460 | 33.8 | 32.6–35.0 | 14.2 | 13.1–15.4 | 42.0 | 39.1–45.2 |

| Czech Republic | 1596 | 41.4 | 38.9–43.9 | 15.6 | 13.4–18.0 | 37.7 | 32.9–43.2 | 5927 | 49.5 | 48.2–50.9 | 27.5 | 26.0–29.0 | 55.5 | 53.0–58.1 |

| Estonia | 262 | 41.2 | 35.0–47.3 | 18.4 | 12.9–24.7 | 44.7 | 33.6–59.3 | 1760 | 50.9 | 48.4–53.2 | 29.1 | 26.3–31.8 | 57.2 | 52.7–62.0 |

| Latvia | 266 | 32.8 | 27.0–38.7 | 15.9 | 10.8–21.9 | 48.4 | 35.8–65.5 | 1012 | 44.1 | 40.9–47.3 | 22.8 | 19.4–26.3 | 51.7 | 45.2–59.0 |

| Lithuania | 312 | 42.2 | 36.3–47.9 | 15.4 | 11.2–20.3 | 36.6 | 28.0–47.6 | 2218 | 54.6 | 52.4–56.7 | 31.3 | 28.8–33.7 | 57.3 | 53.5–61.3 |

| Poland | 627 | 41.6 | 37.7–45.5 | 12.8 | 9.6–16.5 | 30.8 | 23.9–39.6 | 398 | 47.9 | 42.8–52.9 | 17.4 | 12.6–22.9 | 36.4 | 27.5–48.1 |

| Slovakia | 709 | 38.9 | 35.1–42.7 | 13.6 | 10.5–17.0 | 34.8 | 28.0–43.3 | 3092 | 53.9 | 52.0–55.7 | 28.7 | 26.7–30.7 | 53.2 | 50.1–56.5 |

Small Intestine Cancer

Small intestine cancer 1- and 5-year RS was 67.9% and 47.9%, respectively, see Figure 3. Ireland and UK was the region with the worst 1-year patient survival at 58.8%. Croatia was the country with the poorest 1-year RS (53.3%). The Central Europe region had the best 5-year RS for small intestine cancer (53.9%) with the poorest in the Ireland and UK region (36.9%). Wide country variation was identified in 5-year RS from 23.5% in Malta to 58.6% in Switzerland. Five-year conditional survival in patients in Ireland and UK remained significantly below the European average, Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Age-specific and age-standardised relative survival for adult small intestine cancers diagnosed in 2000–2007, by European region, country, gender, and overall.

European patient survival declined with increasing age. Overall 1-, 3- and 5-year age-standardised RS were slightly higher in women compared to men; particularly evident in younger patients, Figure 3.

Overall 5-year RS increased from 40.5% to 48.7% from 1999–2001 until 2005–2007 (Table 5 and supplement 3). The largest improvements (>10% points) in patient survival were observed in Italy, Austria, Czech Republic and Finland. All regions, except Ireland and UK, showed a significant increase in survival from 1999–2001 to 2005–2007.

Table 5.

Five-year relative survival (RS) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) of small intestine cancer in three periods (1999–2001, 2002–2004, 2005–2007) by country, European region and European average, with p-values of differences* between periods.

| Number of cases analysed across all time periods | 1999–2001 | 2002–2004 | 2005–2007 | 2005–2007 vs 1999–2001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | % RS | 95% CI | Abs diff | p-value | ||

| Europe | 18116 | 40.5 | (38.5–42.7) | 45.8 | (43.9–47.9) | 48.7 | (46.9–50.5) | 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Northern EU | 4021 | 49.9 | (46.7–53.3) | 50.7 | (47.7–53.9) | 55.8 | (53.0–58.8) | 6.0 | 0.004 |

| Denmark | 626 | 37.4 | (30.3–46.1) | 37.7 | (30.4–46.6) | 39.6 | (33.2–47.1) | 2.2 | 0.341 |

| Finland | 678 | 51.7 | (43.7–61.2) | 55.4 | (48.8–62.9) | 62.1 | (54.9–70.3) | 10.4 | 0.040 |

| Iceland b | 49 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Norway | 834 | 52.6 | (45.7–60.6) | 51.6 | (45.4–58.6) | 56.6 | (50.5–63.3) | 3.9 | 0.216 |

| Sweden | 1835 | 52.0 | (47.5–57.0) | 53.3 | (48.9–58.1) | 59.5 | (55.3–64.0) | 7.5 | 0.011 |

| Ireland and UK | 7178 | 35.3 | (33.1–37.6) | 36.1 | (34.1–38.3) | 37.7 | (35.7–39.8) | 2.4 | 0.058 |

| Ireland | 376 | 35.5 | (26.2–48.1) | 44.7 | (36.3–55.2) | 42.8 | (34.7–52.9) | 7.3 | 0.154 |

| England | 5539 | 34.4 | (31.9–37.0) | 35.1 | (32.8–37.5) | 37.7 | (35.5–40.2) | 3.4 | 0.027 |

| Northern Ireland | 230 | 37.4 | (27.9–50.2) | 33.9 | (23.0–50.0) | 43.5 | (30.6–61.9) | 6.1 | 0.263 |

| Scotland | 639 | 39.6 | (32.7–48.0) | 37.5 | (30.1–46.7) | 38.4 | (31.9–46.1) | −1.3 | 0.405 |

| Wales | 401 | 38.9 | (28.6–52.7) | 38.2 | (29.6–49.3) | 33.3 | (25.9–42.8) | −5.6 | 0.227 |

| Central EU | 3399 | 44.1 | (40.7–47.8) | 47.8 | (44.5–51.2) | 53.0 | (50.0–56.3) | 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Austria | 899 | 43.6 | (37.3–50.9) | 52.3 | (46.0–59.4) | 55.7 | (50.1–61.9) | 12.1 | 0.004 |

| France | 572 | 45.3 | (39.3–52.3) | 48.3 | (42.2–56.2) | – | – | – | – |

| Germany | 323 | 42.0 | (31.6–56.0) | 45.6 | (34.9–59.6) | 50.1 | (41.2–61.0) | 8.1 | 0.154 |

| Switzerland | 294 | 54.7 | (45.0–66.5) | 59.9 | (50.4–71.0) | 55.4 | (45.4–67.5) | 0.7 | 0.467 |

| The Netherlands | 1737 | 44.5 | (39.6–50.0) | 43.3 | (39.0–48.2) | 51.5 | (47.2–56.3) | 7.1 | 0.022 |

| Southern EU | 1570 | 39.5 | (34.7–44.9) | 49.0 | (44.3–54.2) | 49.7 | (45.5–54.3) | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| Italy | 1338 | 38.7 | (33.5–44.6) | 48.7 | (43.7–54.4) | 51.1 | (46.4–56.3) | 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Malta b | 34 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Slovenia b | 153 | – | – | 48.5 | (33.8–69.6) | – | – | – | – |

| Spain | 347 | 46.3 | (38.4–56.0) | 42.4 | (35.9–50.1) | – | – | – | – |

| Eastern EU | 1951 | 34.5 | (29.4–40.4) | 43.4 | (38.9–48.4) | 43.5 | (39.6–47.8) | 9.1 | 0.005 |

| Bulgaria | 248 | 41.9 | (26.0–67.6) | 35.8 | (25.1–51.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Czech Republic | 849 | 35.8 | (28.3–45.4) | 46.1 | (39.4–54.0) | 46.9 | (41.0–53.6) | 11.0 | 0.020 |

| Estonia b | 95 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lithuania b | 186 | – | – | – | – | 32.9 | (22.0–49.4) | – | – |

| Poland b | 225 | – | – | – | – | 44.7 | (33.7–59.1) | – | – |

| Slovakia | 368 | 51.4 | (39.4–67.1) | 42.0 | (32.2–54.7) | 46.2 | (37.6–56.8) | −5.2 | 0.269 |

Abs = absolute, Diff = Difference.

Survival differences between periods have been assessed by the Z-test.

Standardized Survival rates could not be calculated where one or more age specific rates are absent due to small number of cases.

Note: % difference is the relative difference.

Note: Empty fields of RS in France and Spain in 2007 are due to a limitation of analysis to periods 1999–2001 and 2002–2004 only.

Discussion

European wide variation in patient survival was observed for all three cancer sites investigated between regions. Country-specific patient survival also displayed wide variation with several countries showing inconsistent estimates to their region, including Denmark, the Netherlands, Bulgaria and Croatia. Survival of patients improved modestly from 1999–2001 until 2005–2007 for all cancer sites. Oesophageal and stomach cancer 5-year RS for Europe remained very poor. Small intestine cancer had the best overall 5-year RS in Europe and displayed the largest improvement in patient survival.

Oesophageal cancer

European 1- and 5-year RS for oesophageal cancer patients remained poor (35.8% and 10.6%, respectively). With the exception of Central Europe, which maintained the highest patient survival compared with other European regions as reported in EUROCARE-4 [18], RS in other European regions remained below that reported in the USA [19]. Eastern Europe, where OSCC predominates, continued to have the worst RS. Geographical differences in the proportion of oesophageal cancer patients with histology ‘not otherwise specified’ between regions may account for some of these disparities (data not shown). Additionally, differences in diagnostic accuracy may also account for regional variation with potential misclassification of gastro-oesophageal tumours [20,21]. Cancer stage is a major predictor of cancer patient survival and differences in stage distribution between countries and regions, as a result of early detection and/or diagnostic practices, could also account for some of the observed disparity seen in Eastern Europe [22,23].

Five-year RS for oesophageal cancer patients, for Europe as a whole, increased marginally from 9.8% in 1999–2001 to 12.6% in 2005–2007. Central Europe and Ireland and UK demonstrated the most marked improvement. This may be explained by improvements in surgical techniques, adjuvant therapy, earlier diagnosis and/or centralisation of treatment. The trends in Europe in mortality [24] and incidence [25] in oesophageal cancer vary markedly across the countries in the study, but generally there is tight correlation between them, suggesting that improvements in survival are not due to over-diagnosis arising from increased surveillance. Variation in incidence trends may be caused by regional changes in the risk-factor prevalence [26]. Obesity may be increasing the incidence of OAC particularly in northern and western Europe, while reduction in tobacco and alcohol consumption is reducing the incidence of OSCC [26]. The generally better prognosis of patients diagnosed with EAC is not consistent across Europe [18].

Centralisation of treatment has produced a marked improvement in oesophageal cancer patient survival with many European countries introducing such strategies in recent years. Ireland and UK demonstrated comparatively better patient survival improvements for oesophageal cancer than most Northern European countries in both time frames investigated and in line with the centralisation of cancer services for oesophagogastric cancer surgery implemented in the UK in 2001. While hospitals performing more than 40 oesophagectomies annually had lower 30-day postoperative mortality, this may not fully explain regional differences in oesophageal or gastric cancer patient survival [27]. Other factors, as highlighted by the International Benchmarking Partnership, may be important such as late diagnosis, differences in public awareness of cancer symptoms, cancer stage, morphology and topography, presence of co-morbidities, lifestyle factors such as cigarette smoking, and access to optimum care [28]. Body mass index has also been shown to be a prognostic marker for OSCC [29]. The fact that 5-year conditional patient survival is rather similar across Europe indicates relevant differences in short term mortality and points towards early diagnosis and access to care as important areas to consider with regards to improvement of oesophageal cancer patient treatment and standardisation of care.

Stomach cancer

One- and 5-year RS for stomach cancer patients remained low particularly in comparison to 5-year survival of around 69% achieved in Asia [30]. Compared to Europe, stomach cancer incidence in Asia is high, with a predominance of non-cardia tumours which have better patient survival [31]. Screening programs and more aggressive treatment undoubtedly contribute to the superior survival of patients seen in Asia but similar strategies are unlikely to be cost-effective in comparatively low incidence countries within Europe. Histological and staging variability across Europe may account for some of the differences in stomach cancer patient survival observed between countries. Patient survival improved overall in Europe from 1999–2001 to 2005–2007 particularly in Denmark and the Czech Republic. Both mortality [20] and incidence [32] rates for stomach cancer continue to fall for most countries during the period of this study, suggesting no appreciable surveillance-driven over-diagnosis that could compromise estimated survival improvement. A recent report using data from the World Health Organisation reported lower stomach cancer mortality from 2000 onwards in the UK, the USA, Japan and several European countries [33]. Centralisation of treatment for gastric cancer was implemented in several European countries, including the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands, in recent years despite reports of no survival benefit [27,34] for patients. While 5-year RS was worst in Ireland and UK, improvements in the most recent time period were observed particularly in Wales and England. While delayed diagnosis, first line treatment, or post-operative mortality could explain the patient survival disadvantage in Ireland and UK, other factors appear to be important given the poor 5-year conditional patient survival. Lifestyle differences such as smoking behaviour, co-morbidities, cancer stage and/or subtype could explain the variability observed across countries.

The decreasing 5-year RS in Finland and Norway could be related to the marked decrease in incidence, mainly affecting distal stomach cancer [35], in these countries. Patients with distal stomach cancer have better prognosis, as presented in this report, and this cancer is more responsive to preventative measures than cancers arising in the cardia or proximal stomach. As an effect of this selective incidence decrease, patient with proximal cancers, who carry a worse prognosis, may have become relatively more frequent over time.

Small intestine cancer

European 1- and 5-year RS for patients with epithelial small bowel carcinomas diagnosed from 1978–2002 were comparatively lower than those reported here for all small intestine cancers, excluding lymphomas [14]. Incidence of epithelial small intestine cancers are similar in Ireland and UK and Northern and Southern Europe [14] despite variation in RS. Differences in cancer stage at diagnosis and subtype throughout Europe could explain the reported variations in patient survival. The EUROCARE-5 data encompasses all small intestine cancer histologies with the exception of lymphomas. Small intestine sarcomas reportedly have worse prognosis than neuroendocrine cancers which have a more favourable outcome [8,36]. Small intestine cancers are notoriously difficult to diagnose due to their vague symptoms. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of small intestine cancer patients are associated with poorer prognosis [37]. One-year RS was lower in Ireland and UK as previously reported [14], and also in Denmark and several Eastern European countries, suggesting that delayed diagnosis, at patient, primary care or referral stages, might be an important factor. This would not however explain the poorer 5-year conditional survival estimates in Ireland and UK, Denmark and Malta for those patients who survived the first year post diagnosis.

Improved survival is reported across all European regions particularly in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe for small intestine cancer patients. Increasing trends in small intestine cancer incidence has been reported [11,12,13,38,39] but mortality rates have remained stable or slightly increasing [38,39]. Given the low incidence and mortality rates, and the heterogeneity of tumour types, it is difficult to say whether effective therapy has increased patient survival [40]. Recent improvements in treatment of small intestine sarcomas, with the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors since 2001 [41] may have influenced patient survival. Due to the low incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumours [42], a rare sarcoma sub-type, the effect on patient survival in large datasets like EUROCARE is difficult to measure without ad hoc analyses.

Detailed discussion of the strengths and limitations of the EUROCARE-5 data are available in the article by Rossi et al. in this issue [15]. Increasing survival trends after 5 years of follow-up were found in patients with poor prognosis cancer and aged 75 year and older for Austria, Croatia, Germany, Poland and Slovakia, and may be related to difficulties in the ascertainment of life status [43] or to DCO proportions [15]. Survival estimates from these countries should be interpreted with caution. However, comparing individual countries may provide more meaningful assessment of reasons for disparities in patient survival; this is limited, however, for cancers with low incidence estimates such as small intestine and oesophageal cancer as the standard errors become large. In addition, the % DCO statistic for each country and cancer are available in Table 1, and should inform comparisons being made between individual countries’ patient survival estimates [44].

Conclusions

This article presents overall patient survival for three anatomical sub-sites: oesophagus, stomach and small intestine. They provide some indication of areas that need further investigation to determine the drivers of the variation in survival of cancer patients across Europe. More in-depth investigation by anatomic sub-site and histology could explain the variability observed and are planned using additional data from EUROCARE-5. The historic nature of these large collaborative studies means that recent developments in early detection, routes to treatment, changes to service provision and new treatment modalities for patients will have had insufficient time to have a visible effect. Continued monitoring of cancer survival across Europe will allow further evaluation of survival differences to further promote the widespread application of effective diagnosis and treatment modalities [45]. In summary, although improvements in survival have been reported for cancers of the oesophagus, stomach and small intestine, survival remains poor with wide variation across Europe.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Oesophageal cancer survival remains poor in Europe with wide variability.

Improvements in earlier diagnosis and access to care for oesophageal cancer needed.

Improvement in stomach cancer survival overall in Europe despite variability.

Non-cardia stomach cancers have better survival than cardia cancers.

Significant improvements in small intestine cancer survival observed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chiara Margutti, Simone Bonfarnuzzo and Camilla Amati for secretarial assistance.

Role of funding source

The study was funded by the Compagnia di San Paolo, the Fondazione Cariplo Italy, the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata 2009, RF-2009-1529710) and the European Commission (European Action Against Cancer, EPAAC, Joint Action No20102202). The Northern Ireland Cancer Registry is supported by the Public Health Agency for N. Ireland. Dr Michael Cook is funded by US Federal Funds. The Compagnia di San Paolo, the Fondazione Cariplo Italy, the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata 2009, RF-2009-1529710) and the European Commission (European Action Against Cancer, EPAAC, Joint Action No20102202).

The funding sources had no role in study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sant M, Aareleid T, Berrino F, Bielska Lasota M, Carli PM, Faivre J, et al. EUROCARE-3: survival of cancer patients diagnosed 1990–94–results and commentary. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(Suppl 5):v61–118. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berrino F, De Angelis R, Sant M, Rosso S, Bielska-Lasota M, Lasota MB, et al. Survival for eight major cancers and all cancers combined for European adults diagnosed in 1995–99: results of the EUROCARE-4 study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:773–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE–5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosetti C, Levi F, Ferlay J, Garavello W, Lucchini F, Bertuccio P, et al. Trends in oesophageal cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1118–29. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut. 2015;64:381–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram II, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2014;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdecchia A, Corazziari I, Gatta G, Lisi D, Faivre J, Forman D. Explaining gastric cancer survival differences among European countries. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:737–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qubaiah O, Devesa SS, Platz CE, Huycke MM, Dores GM. Small intestinal cancer: a population-based study of incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1992 to 2006. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1908–18. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haselkorn T, Whittemore AS, Lilienfeld DE. Incidence of small bowel cancer in the United States and worldwide: geographic, temporal, and racial differences. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:781–7. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-3635-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schottenfeld D, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Vigneau FD. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of neoplasia in the small intestine. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsikitis VL, Wertheim BC, Guerrero MA. Trends of incidence and survival of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in the United States: a seer analysis. J Cancer. 2012;3:292–302. doi: 10.7150/jca.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Wayne JD, Ko CY, Bennett CL, Talamonti MS. Small bowel cancer in the United States: changes in epidemiology, treatment, and survival over the last 20 years. Ann Surg. 2009;249:63–71. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Fröbom R, Lagergren J. Incidence patterns of small bowel cancer in a population-based study in Sweden: increase in duodenal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:e158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faivre J, Trama A, De Angelis R, Elferink M, Siesling S, Audisio R, et al. Incidence, prevalence and survival of patients with rare epithelial digestive cancers diagnosed in Europe in 1995–2002. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossi S, Baili P, Caldora M, Carrani E, Minicozzi P, Pierannunzio D, et al. The EUROCARE-5 database, qality checks and methods of statistical analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corazziari I, Quinn M, Capocaccia R. Standard cancer patient population for age standardising survival ratios. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2307–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenner H, Gefeller O. An alternative approach to monitoring cancer patient survival. Cancer. 1996;78:2004–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin AT, Francisci S, Foschi R, Donnelly DW, Lemmens V, Brenner H, et al. Oesophageal cancer survival in Europe: a EUROCARE-4 study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, H M-J. SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988–2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. NIH Pub N National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buas MF, Vaughan TL. Epidemiology and risk factors for gastroesophageal junction tumors: understanding the rising incidence of this disease. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2013;23:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsman WA, Tytgat GNJ, ten Kate FJW, van Lanschot JJB. Differences and similarities of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:160–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters S, Maringe C, Butler J, Brierley JD, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Comparability of stage data in cancer registries in six countries: lessons from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:676–85. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maringe C, Walters S, Butler J, Coleman MP, Hacker N, Hanna L, et al. Stage at diagnosis and ovarian cancer survival: evidence from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, Levi F, Chatenoud L, Negri E, et al. Cancer mortality in Europe, 2005–2009, and an overview of trends since 1980. Ann Oncol. 2013 Oct;24(10):2657–71. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lortet-Tieulent J, Renteria E, Sharp L, Weiderpass E, Comber H, Baas P, et al. Convergence of decreasing male and increasing female incidence rates in major tobacco-related cancers in Europe in 1988–2010. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Jun;51(9):1144–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro C, Bosetti C, Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, Negri E, et al. Patterns and trends in esophageal cancer mortality and incidence in Europe 1980–2011 and predictions to 2015. Ann Oncol. 2014 Jan;25(1):283–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dikken JL, van Sandick JW, Allum WH, Johansson J, Jensen LS, Putter H, et al. Differences in outcomes of oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery across Europe. Br J Surg. 2013;100:83–94. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forbes LJL, Simon AE, Warburton F, Boniface D, Brain KE, Dessaix A, et al. Differences in cancer awareness and beliefs between Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): do they contribute to differences in cancer survival? Br J Cancer. 2013;108:292–300. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe M, Ishimoto T, Baba Y, Nagai Y, Yoshida N, Yamanaka T, et al. Prognostic impact of body mass index in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3984–91. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0163-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yako-Suketomo H, Katanoda K. Comparison of time trends in stomach cancer mortality (1990–2006) in the world, from the WHO mortality database. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:622–3. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnold M, Karim-Kos HE, Coebergh JW, Byrnes G, Antilla A, Ferlay J, et al. Recent trends in incidence of five common cancers in 26 european countries since 1988: Analysis of the european cancer observatory. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Jun;51(9):1164–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuda A, Matsuda T. Time trends in stomach cancer mortality (1950–2008) in Japan, the USA and Europe based on the WHO mortality database. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:932–3. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van de Poll-Franse LV, Lemmens VEPP, Roukema JA, Coebergh JWW, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP. Impact of concentration of oesophageal and gastric cardia cancer surgery on long-term population-based survival. Br J Surg. 2011;98:956–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmassmann A, Oldendorf M-G, Gebbers J-O. Changing incidence of gastric and oesophageal cancer subtypes in central Switzerland between 1982 and 2007. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:603–9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9379-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeeneldin AA, Saber MM, Seif El-Din IA, Frag SA. Small intestinal cancers among adults in an Egyptian district: a clinicopathological study using a population-based cancer registry. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2013;25:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauer RL, Palmer ML, Bauer AM, Nava HR, Douglass HO. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: 21-year review of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:183–8.1. doi: 10.1007/BF02303522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shack LG, Wood HE, Kang JY, Brewster DH, Quinn MJ, Maxwell JD, et al. Small intestinal cancer in England & Wales and Scotland: Time trends in incidence, mortality and survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 May 1;23(9):1297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klint A, Engholm G, Storm HH, Tryggvadottir L, Gislum M, Hakulinen T, et al. Trends in survival of patients diagnosed with cancer of the digestive organs in the nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol. 2010 Jun;49(5):578–607. doi: 10.3109/02841861003739330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karim-Kos HE, Kiemeney LA, Louwman MW, Coebergh JW, de Vries E. Progress against cancer in the netherlands since the late 1980s An epidemiological evaluation. Int J Cancer. 2012 Jun 15;130(12):2981–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demetri GD. Identification and treatment of chemoresistant inoperable or metastatic GIST: experience with the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate (STI571) Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(Suppl 5):S52–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)80603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman MT, Matsuno RK, Shvetsov YB. Racial and ethnic variation in the incidence of small-bowel cancer subtypes in the United States, 1995–2008. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:441–8. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31826b9d0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen MR, Storm HH, Eurocourse Work Package 2 Group Cancer registration, public health and the reform of the European data protection framework: Abandoning or improving european public health research? Eur J Cancer. 2015 Jun;51(9):1028–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson D, Sankila R, Hakulinen T, Moller H. Interpreting international comparisons of cancer survival: The effects of incomplete registration and the presence of death certificate only cases on survival estimates. Eur J Cancer. 2007 Mar;43(5):909–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baili P, Di Salvo F, Marcos-Gragera R, Siesling S, Mallone S, et al. Survival for all cancer patients diagnosed between 1999 and 2007 in Europe: results of EUROCARE-5, a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.