To the editor

Drug-eluting stents (DES) have advanced percutaneous treatment of coronary artery disease by reducing restenosis. However, DES have not eliminated restenosis, can serve as a nidus for thrombosis, and are associated with microvascular and endothelial dysfunction.1,2 We hypothesized that the polymer surface of DES may be damaged during delivery balloon expansion and that microparticles may detach, which could contribute to these limitations.

Methods

We used optical microscopy to systematically image the polymer surface of the 4 US Food and Drug Administration-approved DES following expansion using the accompanying delivery balloon. The manufactures are (in alphabetical order): Abbott Laboratories (“Xience V”); Boston Scientific (“Taxus Liberté”); Cordis (“Cypher”); and Medtronic (“Endeavor”). They are de-identified as DES “A”, “B”, “C” and “D”. A total of 5 stents were tested from each manufacturer in a vacuum filtration system containing a filtered test medium. Each stent came directly from its original package, pre-mounted on its delivery balloon by the manufacture, and not directly handled in anyway. Although each stent was expanded unconstrained, the tests were otherwise conducted under a range of conditions that mimic regulatory submission requirements and the variability seen in clinical practice and to ensure that conclusions on the effect of manufacturer held averaging over a full range of deployment conditions. The 5 conditions – applied to 1 DES from each manufacturer – were: delivery balloon maximum pressure 9.0 atm, 14.0 atm, or 22.0 atm in de-ionized water at 25°C; and 14.0 atm in de-ionized water or plasma at 37°C. For control, a bare metal stent was expanded using the same technique to a maximum inflation pressure of 14.0 atm in de-ionized water at room temperature.

Prior to expansion, the abluminal surface of each stent was imaged. Following expansion, all abluminal and adluminal surfaces were imaged. Additionally, all water and plasma solutions were filtered, and the filter and balloon surfaces imaged to identify any microparticles.

Dispersive Raman spectroscopy was used for definitive identification of microparticles. Kruskil-Wallis tests were performed to assess if the proportion of the total surface area that was damaged differed by manufacturer. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 and statistical significance was defined by P-value<0.05 using 2-sided tests.

Results

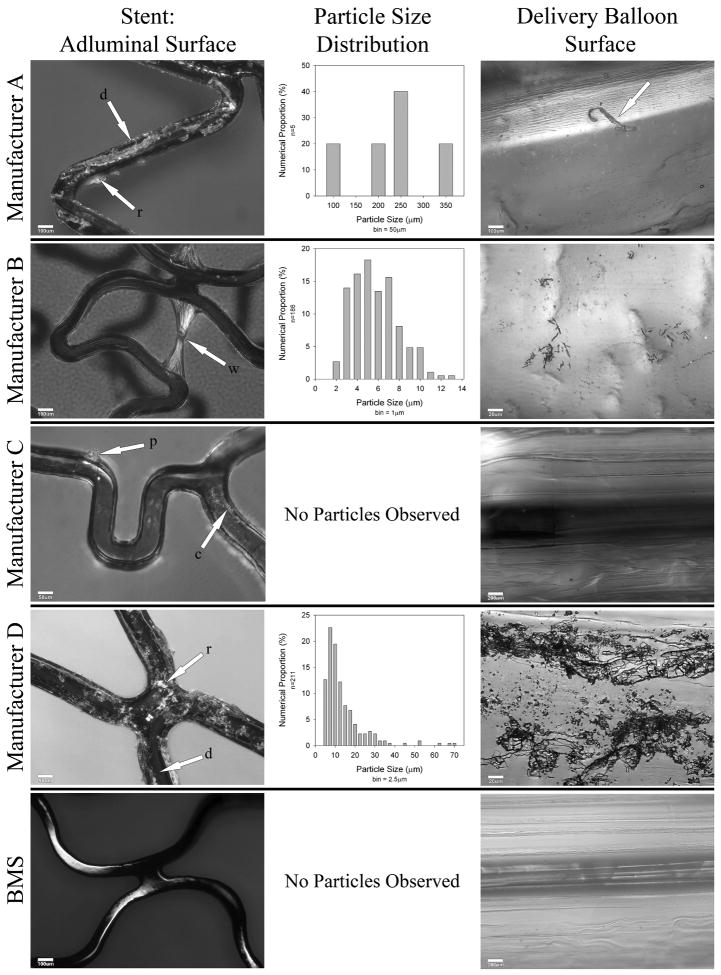

Prior to balloon expansion, the abluminal polymer surface of DES D showed cracks; abluminal surfaces of all other DES appeared homogeneous. Following balloon expansion, the abluminal and adluminal polymer surfaces of all DES were damaged, affecting 4.6% to 100% of the surface area imaged (Figure; Table). No significant differences were observed between various expansion conditions for each particular DES; therefore results were pooled across conditions. Surface damage ranged from deformation (ridging, cracking, peeling and webbing) to complete delamination with visually-confirmed separation of polymer. The dimensions of damage and of detached microparticles ranged from 2 to 350μm. Microparticles from all but DES B were confirmed to be polymer. The extent of damage differed by manufacturer (P<0.001 for adluminal and P=0.002 for abluminal damage).

Figure.

Representative damage to the polymers on the adluminal surface of each DES following balloon expansion, particle size distribution graphs of microparticles shed, and microparticles adherent to delivery balloon. Each stent shown was 3.0 mm in diameter and 16-18 mm in length. The adluminal and abluminal polymer surface of DES were systematically imaged following balloon expansion using optical microscopy (Olympus BX 60; Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). Magnification was 50 to 500×. Each polymer surface was imaged at 16 locations (8 adluminal, 8 abluminal), spanning the length of the DES. The locations were predefined in a spiral configuration. For quantitative measurements, the magnification was 100×. The proportion of the surface area affected by each form of damage relative to the total surface area imaged was determined using quantitative image analysis. For webbing, the area of the 2 bases forming each individual web was used for the calculation.

Manufacture A: The arrows on the polymer surface show areas of delamination (d) and ridging (r). The arrow on the balloon surface points out an adherent large polymer fragment.

Manufacture B: The arrows show webbing (w) of the polymer surface and microparticles adherent to the delivery balloon.

Manufacture C: The arrows point out peeling (p) and cracking (c). No polymer fragments were identified on the filter or balloon surface.

Manufacture D: extensive delamination and ridging can be seen universally.

Additionally, there was significant cracking (not shown), and intermediate-sized polymer fragments adherent to the delivery balloon.

The BMS demonstrates minor surface indentations but no other damage or particle fragments.

DES – drug eluting stent; BMS – bare metal stent.

Definitions of types of damage to polymer: delamination – complete separation of polymer from stent surface; ridging – dislocation without detachment and accumulation of polymer to form an elevated mass on the stent surface; webbing - distortion of the polymer such that material is stretched across and partially obstructs an open cell in between stent struts; peeling - partial – but incomplete - delamination of the polymer which protrudes into the vessel lumen; cracking – fine transection through entire polymer thickness.

Table.

Proportion of polymer surface damaged, microparticles shed and microparticles adherent to delivery balloon.*

| Stent | Proportion Damaged: Adluminal Surface (%) | Proportion Damaged: Abluminal Surface (%) | Microparticles Shed, Trapped by Filter | Microparticles Adherent to Delivery Balloon | Obstruction of Open Cells (webbing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 41.7 (40.4-43.3) (ridging, cracking, peeling, delamination) | 11.8 (9.2-14.5) (cracking, ridging,) | Yes (large size; smallest number) | Yes (small-to-large size; smallest number) | No |

| B | 14.7 (11.7-17.5) (webbing, ridging) | 12.3 (10.1-14.6) (webbing, ridging) | Yes (small size; intermediate number) | Yes (small size; intermediate number) | Yes |

| C | 4.6 (2.3-7.0) (ridging, cracking, peeling) | 7.1 (5.2-9.0) (ridging, cracking) | None observed | None observed | No |

| D | 100 (100-100) (cracking, delamination, ridging, peeling) | 100 (100-100) (cracking, ridging, peeling) | Yes (small-to-moderate size; largest number) | Yes (small-to-large size; largest number) | No |

| BMS | 0 | 0 | None observed | None observed | No |

Across all 5 conditions for each DES (no significant difference existed between different conditions for each particular DES). Principal type of damage is listed in order of frequency. Microparticle description is listed as relative size and number.

Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval).

DES – drug eluting stent; BMS – bare metal stent.

Size definitions: Small – <10μm; Moderate – 10-100μm; Large - >100μm (particles bordering on macroscopic).

Number definitions: Relative to other DES for which microparticles shed or adherent to balloon.

Comment

In this preliminary study, balloon expansion damaged the polymer surface of DES and microparticles detached. The median proportion of total surface damage was associated with polymer type and involved both adluminal and abluminal surfaces.

Polymer damage during balloon expansion of DES has been reported by 2 research groups3,4 but is disputed by others.5 Additionally, case reports of embolization of polymer fragments from other intravascular devices have been described and correlated with subsequent adverse clinical events.6 However, there have been no published reports pertaining to DES.

Polymer damage and detached microparticles could theoretically contribute to DES-associated complications, including thrombosis, restenosis, and microvascular and endothelial dysfunction. Confirmation of our results would be useful and further studies should determine physiological and clinical consequences of polymer damage and microparticle detachment. Additionally, the role of other components of DES—namely, drug and stent superstructure—require investigation. Data from this study may be used to calculate sample size for future biomaterial and engineering studies focusing on polymers and microparticles.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of Florida Gatorade Fund (<$10,000). Drs. Pepine and Batich received support from a National Institute of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR029890) to the University of Florida. The funding sources had no involvement in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and no involvement in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors wish to acknowledge James E. Tcheng, MD, and Harry R. Phillips, III, MD (Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina) for their critical review of the data and contribution to development of this research letter. Neither received compensation for their effort.

Footnotes

Dr. Denardo had full access to all data presented in this research letter and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

No author has any conflict of interest in association with this research, and each has completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Malenka DJ, Kaplan AV, Lucas FL, Sharp SM, Skinner JS. Outcomes following coronary stenting in the era of bare-metal vs the era of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2008;299:2868–2876. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Heuvel M, Sorop O, van Beusekom HM, van der Giessen WJ. Endothelial dysfunction after drug eluting stent implantation. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2009;57:629–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otsuka Y, Chronos NA, Apkarian RP, Robinson KA. Scanning electron microscopic analysis of defects in polymer coatings of three commercially available stents: comparison of BiodivYsio, Taxus and Cypher stents. J Invasive Cardiol. 2007;19:71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basalus MW, Ankone MJ, van Houwelingen GK, de Man FH, von Birgelen C. Coating irregularities of durable polymer-based drug-eluting stents as assessed by scanning electron microscopy. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:157–65. doi: 10.4244/eijv5i1a24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boden M, Richard R, Schwarz MC, Kangas S, Huibregtse B, Barry JJ. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the safety and stability of the TAXUS Paclitaxel-Eluting Coronary Stent. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20:1553–62. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta RI, Mehta RI, Solis OE, et al. Hydrophilic polymer emboli: an under-recognized iatrogenic cause of ischemia and infarct. Mod Pathol. 2010;7:921–30. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]