Abstract

Background

Two doses of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine are 97% effective against measles, but waning antibody immunity and two-dose vaccine failures occur. We administered a third MMR dose (MMR3) to young adults and assessed immunogenicity over 1 year.

Methods

Measles virus (MeV) neutralizing antibody concentrations, cell-mediated immunity (CMI), and IgG antibody avidity were assessed at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year after MMR3.

Results

Of 662 subjects at baseline, 1 (0.2%) was seronegative (<8 mIU/mL) and 23 (3.5%) had low (8-120 mIU/mL) MeV neutralizing antibodies. At 1-month post-MMR3, 1 (0.2%) subject was seronegative and 6 (0.9%) had low neutralizing antibodies with only 21/662 (3.2%) showing a ≥4-fold rise in neutralizing antibodies. At 1-year post-MMR3, none were negative and 10 (1.6%) of 617 subjects had low neutralizing antibodies. CMI results showed low-levels of spot-forming cells after stimulation, suggesting T-cell memory, but the response was minimal post-MMR3. MeV IgG avidity results did not correlate with neutralization results.

Conclusions

Most subjects were seropositive pre-MMR3 and very few had a secondary immune response post-MMR3. Similarly, CMI and avidity results showed minimal qualitative improvements in immune response post-MMR3. We did not find compelling data to support a routine third dose of MMR vaccine.

Keywords: measles, third dose measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, measles vaccine immunogenicity, vaccine preventable disease, immunization, cell-mediated immunity, measles virus antibody avidity

Background

Measles is a contagious, viral rash illness; complications including pneumonia and encephalitis can result in death[1]. High two-dose measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination coverage and improved measles control in the World Health Organization (WHO) Region of the Americas resulted in the declaration of measles elimination in the U.S. in 2000[2].

Two doses of MMR vaccine are generally sufficient to provide long-lasting protection against measles[3]. Nonetheless, measles virus (MeV) is one of three components in the MMR vaccine, and third doses have been administered during mumps outbreaks among highly vaccinated populations[4, 5] and in non-outbreak settings among healthcare personnel, military recruits, international travelers, and college students who may have been two-dose vaccinated but lacked documentation[6-8].

The immunogenicity of the MeV component of a third MMR dose has not been studied. We assessed the magnitude and duration of an aggregate MeV neutralizing antibody response, cell-mediated immune response, and IgG antibody avidity before and after a third MMR dose (MMR3) in a healthy, young adult population.

Methods

Setting

The study population comprised patients of the Marshfield Clinic, a private, multispecialty group practice with regional centers throughout central and northern Wisconsin. The Clinic maintains an electronic vaccination registry (www.recin.org) for immunizations administered by Marshfield Clinic providers, local public health agencies, and immunization providers. No measles cases were reported in the area during the study period.

Subjects

Two cohorts comprising 685 subjects were enrolled during 2009-2010. Cohort 1 (N=113 subjects) participated in a 10-year longitudinal study at the Marshfield Clinic examining immunogenicity and adverse events following the second MMR vaccine dose, hereafter called the longitudinal study[9, 10]. To achieve adequate sample size, Marshfield's vaccination registry was used to recruit subjects from Cohort 2 who had two documented MMR doses but did not participate in the longitudinal study (N=572 subjects). Invitation letters were mailed to both cohorts and follow-up phone calls were made. Additionally, Cohort 1 subjects who participated in the measles cell-mediated immunity (CMI) sub-study during the longitudinal study were asked to participate in the current CMI sub-study.

Although only 16 (14.2%) Cohort 1 subjects had low or negative MeV antibody concentrations during the longitudinal study, 93/113 Cohort 1 subjects with ≥1 low or negative antibody concentration to measles, mumps, or rubella during the longitudinal study (defined previously[10-12]) and all Cohort 2 subjects were offered a third dose of MMR vaccine (M-M-R II; Merck & Co.). Serum was collected from all subjects immediately before (baseline), and one month and one year after MMR3.

Study design

At each visit, subjects were questioned about measles disease, exposures, vaccinations, and other health events. MMR vaccine was administered during the initial visit. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Institutional Review Boards of the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved the study. Sample size determination and exclusion criteria were previously described[13].

Cell-mediated immunity sub-study

The 60 participants of the longitudinal measles CMI sub-study or subjects with a low or negative MeV antibody concentration on ≥1 serum specimen draw during the longitudinal study were asked to participate in the current CMI sub-study. However, only 34 (56.7%) subjects meeting these criteria were re-enrolled. A convenience sample from Cohort 2 was used to reach the recruitment goal of 60 subjects.

Laboratory Methods

Laboratory testing was performed at the end of the study. Other than each subject's unique identifier code and serum collection dates, laboratories were blinded to study information.

Plaque reduction neutralization

Plaque reduction neutralization (PRN) testing was performed using low-passage Edmonston MeV on Vero cell monolayers, as previously described[14]. Endpoints were determined for all serum samples tested and ND50 titers calculated using the Kärber method. Serial four-fold dilutions of serum were tested in duplicate starting at 1:8 and ending at 1:8192 against virus diluted to give 25-35 plaques/well and run in parallel with the Second WHO International Standard Reference Serum (66/202). After incubating the virus-serum mixtures at 37° C with 5% CO2, the mixtures were transferred onto corresponding 24-well tissue culture plates containing confluent Vero monolayers; after incubating for 1 hour at 37° C, the inoculum was removed and cells overlaid with medium containing carboxymethylcellulose and returned to the incubator for 5 days prior to staining with neutral red and plaque counting. Serum samples from individual subjects were tested in the same assay run. Titers were standardized against the WHO reference serum with a titer of 1:8 corresponding to 8 mIU/mL in this assay.

Cell-mediated immunity

Cryo-preserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were thawed and cultured overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C with Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) media supplemented with 4% human serum type AB (Lonza), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% 200 mM L-glutamine. Following the overnight culture, IFN-γ production by T-cells was assessed using enzyme-linked immunospot assays of PBMCs (5×105 cells/well), as previously described[15]. PBMCs were stimulated either with a mixture of MeV hemagglutinin, fusion, and nucleoprotein proteins as 20 amino acid peptides (11 amino acids overlapping) at 1μg/mL or with a lysate from MeV-infected Vero cells (Advanced Biotechnologies) at 10μg/mL for 40 hours. RPMI media and Con A (5μg/mL) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. After stimulation, the plates were incubated with biotin-conjugated antibodies to human IFN-γ, then developed and read, as previously described[15]. Low and positive T-cell responses were categorized as <20 and ≥20 spot-forming cells (s.f.c.)/million PBMCs, respectively.

Avidity

MeV IgG antibody avidity was evaluated to determine whether there was a correlation between neutralizing antibody concentrations and strength of antibody binding. Avidity testing occurred after neutralization results were available using the method described previously[16]. Serum samples from all 662 subjects were split into quartiles based on baseline PRN antibody concentration. Subjects with negative neutralizing antibody concentrations were negative for MeV IgG by the Captia Measles IgG enzyme immunoassay assay (Trinity Biotech, Jamestown, NY), thus avidity could not be measured. All subjects with low MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations at baseline, 1-month, or 1-year post-MMR3 were tested for MeV antibody avidity. A random number generator selected specimens from at least 10 subjects from each of the remaining 3 quartiles for avidity testing of 59 subjects. The specimen was classified as negative if at 1:21 dilution it had undetectable IgG by the Captia assay, low avidity if the end titer avidity index percentages (etAI%) were ≤30%, intermediate between 30%-70% (intermediate results were retested), or high avidity if the etAI% was ≥70%.

Data analysis

Based on previous studies[17, 18], serum samples were categorized as: (1) negative (<8 mIU/mL), susceptible to infection and disease; (2) low (8-120 mIU/mL), potentially susceptible to infection and disease; (3) medium (121-900 mIU/mL), potentially susceptible to infection but not disease; and (4) high (>900 mIU/mL), not susceptible to infection or disease. Serum samples were also dichotomized as potentially susceptible (<121 mIU/mL) and not susceptible (≥121 mIU/mL).

We combined Cohorts 1 and 2 during analysis because there were no statistically significant differences between the cohorts by sex, race/ethnicity, or age. However, Cohort 1 had significantly lower geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) of MeV neutralizing antibody at baseline (p=0.0289), so we stratified the chi-squared risk factor analysis at 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3 by baseline MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations.

Mantel-Haenszel chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were run to assess categorical variables. Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests were used for continuous variables. Potential risk factors for negative or low MeV neutralizing antibody levels included: sex, age at first MMR dose, time since second MMR dose (we used <15 years versus ≥15 years prior based on average age of subjects at enrollment minus the age when the second dose was recommended), and (for post-MMR3 serum samples) the binary variable of whether the subject had low or negative MeV neutralizing antibody levels at baseline. In multivariate logistic regression, a backwards selection approach that used p-values <0.4 for inclusion and <0.05 for retention identified factors independently associated with negative or low MeV neutralizing antibody levels at baseline, 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3.

For the CMI analysis, the mean number of spot-forming cells resulting from PBMC stimulation with MeV peptide and MeV lysate was determined at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year post-MMR3. The MeV-specific T-cell response was calculated by subtracting the mean spontaneous response (no stimulation) from the mean peptide or lysate response. MeV T-cell responses were correlated with MeV neutralizing antibody levels at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year post-MMR3. For the avidity analysis, end titer avidity index percentages were correlated with MeV neutralizing antibody levels at all 3 time points.

GMCs of MeV neutralizing antibody were calculated from base 2 log-transformed data. Statistical significance was assigned for P-values <0.05. Data were analyzed with SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC). Reverse cumulative distribution curves were created in Excel to compare the shift in curves from baseline, 1-month, and 1-year post-MMR3.

Results

Enrollment

We contacted 194/200 persons from the longitudinal study; 113 (58.2%) were enrolled, 45 (23.2%) refused, and 36 (18.5%) were ineligible (15 had previously received MMR3 and 21 had other reasons). To achieve adequate sample size, we contacted 1379 (76.8%) of an additional 1795 persons. Of those, 572 (41.4%) were enrolled, 664 (48.2%) refused, and 143 (10.4%) were ineligible (4 had previously received MMR3 and 139 had other reasons)(Supplementary Figure 1).

Baseline serum samples were obtained from 685 enrolled subjects. We excluded 20 (2.9%) Cohort 1 subjects who had medium or high antibody concentrations for all 3 antigens throughout the longitudinal study and were, therefore, not given MMR3. An additional 3 (0.4%) were excluded because they only had baseline samples. There were 662 (96.6%) subjects who received MMR3 and completed the 1-month draw; 617 (92.6%) completed the 1-year draw. Subjects were aged 18-28 years, (mean: 20.8 years, standard deviation: +/-2.1); 294 (44.4%) were male and 649 (98.0%) were self-declared non-Hispanic, white. The mean interval between the second and third MMR doses was 15.8 years (range: 6.7–20.4 years).

MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations pre- and post-MMR3

Of 662 subjects at baseline, 1 (0.2%) was seronegative, 23 (3.5%) had low MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations, 337 (50.9%) had medium concentrations, and 301 (45.5%) had high concentrations (Figure 1). The seronegative subject was a female aged 20 years who received her last MMR dose 18 years prior. At 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3, she had medium MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations. Of 23 subjects with low baseline antibody concentrations, 1 was negative, 5 were low, 14 were medium, and 3 were high 1-month post-MMR3. One year post-MMR3, 19 of 23 had sera drawn; 5 had low, 14 had medium, and 0 had high MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels at baseline, 1 month, and 1 year following a third dose of MMR vaccine.

Overall, at 1-month post-MMR3, 1/662 (0.2%) subjects had no detectable MeV neutralizing antibodies, 6 (0.9%) had low, 256 (38.7%) had medium, and 399 (60.3%) had high neutralizing antibody concentrations. One year post-MMR3, all 617 subjects who returned were positive for MeV neutralizing antibodies: 10 (1.6%) had low, 299 (48.5%) had medium, and 308 (49.9%) had high neutralizing antibody concentrations.

When assessed as a continuous variable, subjects with low or negative baseline MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations were more likely to have low or negative antibody concentrations 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3. Whereas subjects with high baseline concentrations were more likely to have high neutralizing antibody concentrations at 1 month (R2=0.54, P<0.0001) and 1 year (R2=0.68, P<0.0001)(Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A. Comparison of individual measles antibody concentration levels at baseline and 1 month following a third dose of MMR vaccine. R2=0.54, p<0.0001. B. Comparison of individual measles antibody concentration levels at baseline and 1 year following a third dose of MMR vaccine. R2=0.68, p<0.0001. For both figures, data points are represented by circles and they show the comparison result for each subject. The dark solid line represents the best-fit of the comparison. The light shading around the line represents the 95% confidence limits. The dotted lines represent 95% prediction limits.

GMCs were significantly different between baseline and 1-month post-MMR3 (727 vs. 1060 mIU/mL, P<0.0001), and between baseline and 1-year post-MMR3 (727 vs. 843 mIU/mL, P<0.05). However, the reverse cumulative distribution curves show the shift in MeV antibody concentrations from baseline to 1-month to 1-year post-MMR3 was minimal (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reverse cumulative distribution curve by percent of subjects who had measles virus neutralizing antibody concentrations at baseline, 1 month, and 1 year following a third dose of MMR vaccine.

Four-fold rises

Twenty-one (3.2%) of 662 subjects had ≥4-fold rises from baseline to 1-month post-MMR3, of whom at baseline 1 was seronegative, 8 had low antibody concentrations, and 12 had medium PRN concentrations. Eight (1.3%) of 617 subjects had ≥4-fold rises from baseline to 1-year post-vaccination, of whom at baseline 1 was seronegative, 4 had low concentrations, and 3 had medium PRN concentrations.

Risk factors for negative or low MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations pre- and post-MMR3

The unadjusted odds ratios showed that those who had their first MMR dose at age 12-<15 months ([Odds Ratio] OR:3.47, [Confidence Interval] CI:1.24–9.72, p=0.01) had a higher odds of having lower or negative baseline antibody concentrations compared with those who had their first dose at age ≥15 months, and those who had their second MMR dose <15 years prior had a lower odds of having low or negative baseline MeV neutralizing antibody levels versus those who had their second dose ≥15 years prior (OR:0.22, CI:0.05–0.93, p=0.03)(Table 1).

Table 1. Risk factors for negative or low measles neutralizing antibody concentrations at baseline, 1 month, and 1 year after receiving a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine.

| Baseline N= 662 |

1 Month Post-MMR3 N= 662 |

1 Year Post-MMR3 N= 617 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI)1 |

p-value2 | Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate p-value |

Adjusted OR3 (95% CI) |

p- value |

Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate p-value |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p- value |

Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

Multivariate p-value |

|

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 0.56 (0.24-1.28) | 0.16 | 0.53 (0.23- 1.23) | 0.14 | 0.22 (0.03-1.45) | 0.08 | 0.16 (0.02- 1.48) | 0.11 | 0.34 (0.06-1.80) | 0.04* | 0.19 (0.04-0.99) | 0.049* |

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Age at 1st MMR dose | ||||||||||||

| 12- <15 months | 3.47 (1.24- 9.72) | 0.01* | 3.94 (1.37- 11.30) | 0.01* | 0.83 (0.09-7.57) | 0.15 | — | — | 1.37 (0.19-9.74) | 0.90 | — | — |

| ≥15 months | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Time since 2nd MMR dose | ||||||||||||

| <15 years | 0.22 (0.05- 0.93) | 0.03* | 0.18 (0.04-0.80) | 0.02* | 1.75 (0.20-15.29) | 0.79 | — | — | 2.38 (0.49-11.61) | 0.26 | 2.64 (0.50-14.04) | 0.25 |

| ≥15 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Baseline antibody concentrations | ||||||||||||

| <121mIU/mL | N.A.4 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 195.8 (21.8- >999.9) | <0.0001* | N.A. | N.A. | 54.95 (10.90- 277.14) | <0.0001* |

| ≥121 mIU/mL | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | Reference | N.A. | N.A. | Reference | ||

OR= Odds Ratio, CI= Confidence Interval

Statistical Significance at p<0.05 is represented by an asterisk.

Adjusted by controlling for baseline measles antibody concentrations.

N. A. means not applicable. (By default, baseline measles neutralizing antibody concentrations could not be a risk factor at baseline. We were also unable to assess baseline neutralizing antibody concentrations at 1 month or 1 year post-MMR3 during univariate analysis because this was the variable we adjusted for to account for the statistical differences between Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. This adjustment allowed us to combine the cohorts during the analysis to increase our power. However, it is of note that the unadjusted OR's for baseline neutralizing antibody concentrations were highly significant at 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3.)

Of 50 (7.6%) subjects who received their first dose at age 12-<15 months, 5 (10.0%) had negative or low baseline MeV antibody concentrations, versus 19/612 (3.1%) subjects who were vaccinated with their first dose at age ≥15 months. Of 190 (28.7%) subjects who received their second dose <15 years prior, 2 (1.1%) had negative or low baseline MeV antibody concentrations, versus 22/472 (4.7%) subjects who received their second dose ≥15 years prior. In multivariate analysis, having the first MMR dose at 12-<15 months of age remained a significant risk factor at baseline (OR:3.94,CI:1.37–11.30, p=0.01), and those who had their second MMR dose <15 years prior continued to have a lower odds of having low or negative MeV antibody concentrations (OR:0.18,CI:0.04–0.80, p=0.02).

At 1-month post-MMR3, there were no significant risk factors for having low or negative MeV antibody concentrations when adjusting the chi-squared analysis by controlling for baseline GMCs. In multivariate analysis, a significant risk factor for negative or low MeV antibody concentrations 1-month post-MMR3 was whether a subject had low or negative baseline MeV antibody concentrations (OR:195.8,CI:21.8–>999.9, p<0.0001).

At 1-year post-MMR3, females had a lower odds of having low or negative MeV antibodies (OR:0.34, CI:0.06–1.80, p=0.04) versus males when adjusting the chi-squared analysis by controlling for baseline GMCs. In multivariate analysis at 1-year post-MMR3, being female remained protective (OR:0.19, CI:0.04–0.99, p=0.049) and low or negative baseline MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations were a risk factor (OR:54.95, CI:10.90–277.14, p<0.0001).

Cell-mediated immunity

Of 60 CMI sub-study subjects, 7 were excluded (6 did not receive MMR3 and 1 had insufficient blood drawn); 1 (1.9%) of 53 subjects missed the 1-month draw and 6 (11.3%) missed the 1-year draw. MeV lysate stimulation results were missing for an additional 2 subjects at baseline and 1 subject at 1 month. Positive controls were positive for all CMI subjects, indicating viable cells capable of spot-formation. The unstimulated T-cell mean spot-forming cells (s.f.c.)/million PBMCs was 0.1±0.1 at baseline, 0.1±0.1 at 1-month, and 0.2±0.2 at 1-year post-MMR3.

Of 53 CMI sub-study subjects, none had negative baseline MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations and 5 (9.4%) had low baseline concentrations, of whom, 1 had a positive baseline CMI response (≥20 s.f.c./million PBMCs) to peptide stimulation and none had a positive baseline response to lysate stimulation. Only 13/48 (27.1%) subjects with medium or high baseline MeV neutralizing antibodies had a positive baseline CMI result by peptide stimulation and 7/46 (15.2%) subjects had a positive baseline CMI result by lysate stimulation.

The spot-forming cells/million PBMCs were generally higher with peptide stimulation compared to lysate stimulation. At baseline, the MeV peptide mean spot-forming cells was 19.6±9.3 s.f.c./million PBMCs compared to 11.9±7.2 s.f.c./million PBMCs by lysate stimulation. At 1-month post-MMR3, the MeV peptide mean spot-forming cells was 18.5±7.6 s.f.c./million PBMCs, with 13/52 (25.0%) specimens positive by peptide stimulation, compared with 7.3±2.9 s.f.c./million PBMCs, with 5/51 (9.8%) specimens positive by lysate stimulation. At 1-year post-MMR3, the mean spot-forming cells was 29.7±15.9 s.f.c./million PBMCs, with 14/47 (29.8%) positive by peptide stimulation, compared with 10.3±6.4 s.f.c./million PBMCs, with 7/47 (14.9%) specimens positive by lysate stimulation.

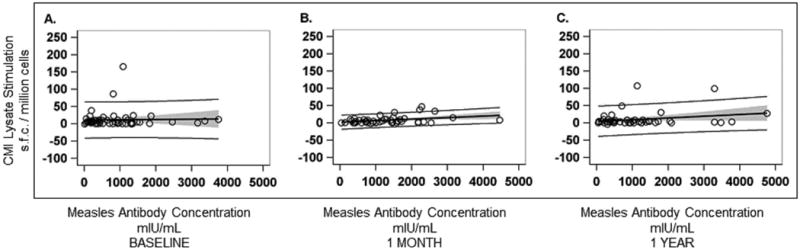

Baseline MeV antibody concentrations did not correlate with baseline MeV T-cell responses to peptide stimulation (R2=0.002, p=0.73) or lysate stimulation (R2=0.0008, p=0.85)(Figure 4). MeV antibody concentrations at 1-month post-MMR3 correlated with MeV T-cell responses at 1 month by peptide stimulation (R2=0.30, p<0.0001), but the correlation did not remain after removing the 2 outliers (R2=0.05, p=0.13). There was no correlation between MeV antibody concentrations and lysate stimulation at 1 month (R2=0.001, p=0.80), but after removing the outlier, there was a correlation (R2=0.14, p=0.007). At 1-year post-MMR3, there was a significant correlation between MeV antibody concentrations and MeV T-cell responses by peptide stimulation (R2=0.17, p=0.004), but no correlation by lysate stimulation (R2=0.06, p=0.09).

Figure 4.

Figure 4a: A. Comparison of baseline measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and baseline measles virus T-cell response to measles virus peptide stimulation (spot-forming cells [s.f.c.]/ million cells), n= 53. R2= 0.002, p=0.73. B. Comparison of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and measles virus T-cell response to measles virus peptide stimulation (s.f.c./ million cells) 1 month after receiving a third dose of MMR vaccine, n=50. R2=0.05, p=0.13 (Note that 2 outliers were removed from the figure). When the 2 outliers were included, the results were: n=52. R2= 0.30, p<0.0001, and the x-axis on the graph extended beyond 40,000 mIU/mL. C. Comparison of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and measles virus T-cell response to measles virus peptide stimulation (s.f.c./ million cells) 1 year after receiving a third dose of MMR vaccine, n=47. R2= 0.17, p=0.004. For all figures, data points are represented by circles and they show the comparison result for each subject. The dark solid line represents the best-fit of the comparison. The light shading around the line represents the 95% confidence limits. The dotted lines represent 95% prediction limits.

Figure 4b: A. Comparison of baseline measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and baseline measles virus T-cell response to measles virus lysate stimulation (s.f.c./ million cells), n=51. R2= 0.0008, p=0.85. B. Comparison of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and measles virus T-cell response to measles virus lysate stimulation (s.f.c./ million cells) 1 month after receiving a third dose of MMR vaccine, n=49. R2= 0.14, p=0.007 (Note that 1 outlier was removed from the figure; the other outlier was already missing because of insufficient blood drawn to analyze the measles virus lysate response). When the outlier was included, the results were: n=50. R2=0.001, p=0.80, and the x-axis on the graph extended beyond 40,000 mIU/mL. C. Comparison of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and measles virus T-cell response to measles virus lysate stimulation (s.f.c./ million cells) 1 year after receiving a third dose of MMR vaccine, n=47. R2=0.06, p=0.09. For all figures, data points are represented by circles and they show the comparison result for each subject. The dark solid line represents the best-fit of the comparison. The light shading around the line represents the 95% confidence limits. The dotted lines represent 95% prediction limits.

Avidity

Overall, 38/59 (64.4%) subjects evaluated had MeV antibodies with high avidity at baseline (Table 2), including 7/24 (29.2%) subjects with low MeV antibody concentrations at baseline. The avidity results did not correlate with MeV antibody concentrations at baseline (R2=0.07, p=0.07), 1-month (R2=0.01, p=0.50) or 1-year (R2=0.02, p=0.31) post-MMR3 (Figure 5).

Table 2. Measles virus neutralizing antibody geometric mean concentrations by plaque reduction neutralization in correlation with measles virus antibody avidity levels by end titer avidity index percentages at baseline, 1 month, and 1 year after receiving a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine.

| BASELINE | 1 MONTH POST-MMR3 | 1 YEAR POST-MMR31 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Measles Neutralizing Antibody Concentrations |

Avidity Index | Measles Neutralizing Antibody Concentrations |

Avidity Index | Measles Neutralizing Antibody Concentrations |

Avidity Index | |||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Quartile2 | n | GMC (mIU/mL)3 | Mean4 | Neg5 (%) | Low (%) | Int (%) | High (%) | GMC (mIU/mL) | Mean | Neg (%) | Low (%) | Int (%) | High (%) | GMC (mIU/mL) | Mean | Neg (%) | Low (%) | Int (%) | High (%) | Miss (%) |

| 1 | 27 | 69 | 71 | 8 (29.6) | 0 | 10 (37.0) | 9 (33.3) | 249 | 75 | 2 (7.4) | 0 | 5 (18.5) | 20 (74.1) | 143 | 73 | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 6 (22.2) | 16 (59.3) | 4 (14.8) |

| 2 | 11 | 556 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (100) | 606 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (100) | 466 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) |

| 3 | 11 | 990 | 79 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | 1222 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (100) | 750 | 79 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | 0 |

| 4 | 10 | 2130 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 2435 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 2225 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 3 (30) | 7 (70) | 0 |

| Total | 59 | 299 | 75 | 8 | 0 | 13 | 38 | 582 | 77 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 50 | 415 | 77 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 43 | 5 |

Five subjects were missing data at one year.

Quartiles were established based on baseline plaque reduction neutralization measles antibody concentration. Subjects with the lowest baseline measles neutralizing antibody concentrations were placed in Quartile 1 and subjects with the highest baseline measles neutralizing antibody concentrations were placed in Quartile 4. The number of subjects selected from Quartile 1 is more than from the other 3 quartiles, because we tested the avidity on every subject who had a negative or low measles neutralizing antibody concentration during at least 1 time point. Of note, 24 of 27 subjects in Quartile 1 had a negative or low baseline measles antibody concentration; the remaining 3 subjects in Quartile 1 had a medium neutralizing antibody concentration at baseline (but were still in the lowest quartile).

Abbreviations used: GMC means Geometric Mean Concentration, Neg means negative, Int means intermediate, Miss means missing

The mean avidity index excludes the negative specimens by Captia Measles IgG enzyme immunoassay since avidity could not be run on those specimens.

Negative means that at 1:21 dilution, the specimen had undetectable IgG by the Captia Measles IgG enzyme immunoassay.

Figure 5.

A. Comparison of baseline measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and baseline measles virus antibody avidity levels (end titer avidity index percentage [etAI%]), n= 51. R2=0.07, p=0.07. B. Comparison of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and measles virus antibody avidity levels (etAI%) 1 month after receiving a third dose of MMR vaccine, n=51. R2=0.01, p=0.50. C. Comparison of measles virus neutralizing antibody concentration levels (mIU/mL) and measles virus antibody avidity levels (etAI%) 1 year after receiving a third dose of MMR vaccine, n=47. R2=0.02, p=0.31. For all figures, data points are represented by circles and they show the comparison result for each subject. The dark solid line represents the best-fit of the comparison. The light shading around the line represents the 95% confidence limits. The dotted lines represent 95% prediction limits.

Discussion

A modest but significant boost in MeV geometric mean neutralizing antibody concentrations occurred 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3 compared with baseline. However, almost all subjects were MeV seropositive prior to receiving MMR3, and subjects' antibody levels returned to near-baseline 1-year post-vaccination. Nonetheless, for the 24 (3.6%) subjects with low or negative baseline MeV antibody concentrations, 18 (75%) moved into medium or high categories at 1 month, of whom, 12 (67%) remained medium or high at 1 year. Among the subsets tested for CMI and avidity, we did not find compelling qualitative data to support a routine third dose of MMR vaccine.

The second MMR vaccine dose was recommended to provide measles immunity to individuals who failed to respond to the first dose[19]; two doses are 97% effective at preventing measles[20, 21]. Although 95% of vaccinated persons have detectable MeV antibodies 10-15 years after the second MMR dose[10, 22], waning immunity occurs after two doses[10][23], and two-dose failures have been documented[24].

Having a low or negative baseline MeV antibody concentration was the biggest risk factor for low or negative antibody concentrations 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3, suggesting that inherent biology may be partially responsible for a person's measles antibody levels[10, 25]. Although our results concurred with other reports that timing of administration of the first and second MMR doses significantly affected MeV antibody levels later in life[26, 27], our findings represented only a small proportion of the study population (only 50 [7.6%] subjects received their first dose at age 12-<15 months).

Most subjects did not have a positive CMI result at baseline, despite the majority of subjects having medium or high baseline MeV antibody concentrations. Nonetheless, low-levels of spot-forming cells generally occurred for most specimens after stimulation, suggesting T-cell memory. However, this was not greatly boosted by MMR3. After removing outliers, we found mixed results at 1-month post-MMR3 with no correlation between MeV antibody response and MeV T-cell response by peptide stimulation, but a significant correlation by lysate stimulation. Although we did find a significant correlation between CMI response by peptide stimulation and MeV antibody concentration at 1-year post-MMR3, <1/3 of subjects had positive cell-mediated responses by peptide stimulation and even fewer had positive responses by lysate stimulation at 1 year. These findings could have been because transient increases in circulating MeV-specific T-cells were missed due to specimen collection timing (antigen-stimulated T-cell responses typically peak 2 weeks post-vaccination[28], whereas samples were taken 1-month and 1-year post-MMR3). Other studies assessing antibody and T-cell responses after a second MMR dose showed no correlation[29, 30]. Another possibility is that numbers of T-cells producing IFN-γ in response to MeV did not increase post-MMR3 due to lack of infection by vaccine virus in the presence of neutralizing antibodies.

The MeV IgG avidity results did not correlate with neutralization results. Most subjects reached an IgG avidity plateau. Typically, IgG avidity maturation for measles shifts from low to high 4 months following immunization or infection[16] which might negate additional increases in antibody avidity with subsequent doses of measles-containing vaccine. Nonetheless, only 29% of subjects with low baseline MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations had high avidity results at baseline. It could be interpreted that subjects with poor antibody response and intermediate avidity results were potentially susceptible prior to revaccination. However, the avidity results are an average of the measles IgG and should be interpreted cautiously, since whole MeV is used as the target antigen in the avidity assay, whereas the neutralization assay measures antibodies that bind MeV surface glycoproteins[31].

Our study had additional limitations. Subjects were not representative of the U.S. population. Selection bias may have occurred in Cohort 1, because MMR3 was only offered to those who had a low or negative measles, mumps, or rubella antibody concentration during the longitudinal study.

Overall, MeV neutralizing antibody concentrations initially increased after MMR3 but declined to near-baseline levels one year later. Although our findings showed that MMR3 increased antibody levels for the small percentage of subjects with low MeV neutralizing antibody concentration levels who were on the cusp of protection, the CMI and avidity results in the subset tested showed that MMR3 did not result in substantial improvements in the quality of the immune response. While a third MMR dose may successfully immunize the rare individual who failed to respond after two doses, MMR3 is unlikely to solve the problem of waning immunity in the U.S. A better strategy for maintaining U.S. measles elimination would be to improve vaccination coverage in pockets of unvaccinated individuals and maintain high two-dose coverage nationally with the current two-dose MMR recommendation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Flow chart for enrollment, analysis, and vaccination of subjects with a third dose of MMR vaccine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Charles LeBaron, MD, for his instrumental role in helping develop the protocol and launch the study, Susan Cleveland and Terry Maricle for their assistance with the contract, Jennifer Meece, PhD, Tamara Kronenwetter Koepel, BS, and Donna David, BS, for their laboratory contributions, Sarah Kopitzke, MS, and Carla Rottscheit, BS, for designing the database, and Rebecca Dahl, MPH, for her assistance with the figures.

Funding: No external funding sources were used to gather the data, analyze the data, or summarize the findings. Funding for this study was provided to the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Laura A. Coleman worked for Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation at the time of the study, but she currently works for Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH. All other coauthors do not report any conflict of interest.

Meetings: The MeV neutralizing antibody results were presented at the Infectious Disease Week Conference, October 8-12, 2014, Philadelphia, PA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Food and Drug Administration.

References

- 1.Strebel PM, Papania MJ, Parker Fiebelkorn A, Halsey NA. Measles Vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit P, editors. Vaccines. 6. Elsevier Saunders; 2013. pp. 352–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz SL, Hinman AR. Summary and conclusions: measles elimination meeting, 16-17 March 2000. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(Suppl 1):S43–7. doi: 10.1086/377696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz LE, Preblud SR, Fine PE, Orenstein WA. Duration of live measles vaccine-induced immunity. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9(2):101–10. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogbuanu IU, Kutty PK, Hudson JM, et al. Impact of a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine on a mumps outbreak. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1567–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson GE, Aguon A, Valencia E, et al. Epidemiology of a Mumps Outbreak in a Highly Vaccinated Island Population and Use of a Third Dose of Measles-Mumps-Rubella Vaccine for Outbreak Control- Guam 2009-2010. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318279f593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Advisory Committee on Immunization P, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Immunization of health-care personnel: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR-7):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Military Vaccine Agency. [August 29];Mumps Infection and Mumps Vaccine: Information Paper. Available at: http://www.vaccines.mil/documents/1485MIP-Mumps.pdf.

- 8.McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS. Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-04):1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBaron CW, Bi D, Sullivan BJ, Beck C, Gargiullo P. Evaluation of potentially common adverse events associated with the first and second doses of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1422–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeBaron CW, Beeler J, Sullivan BJ, et al. Persistence of measles antibodies after 2 doses of measles vaccine in a postelimination environment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):294–301. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeBaron CW, Forghani B, Beck C, et al. Persistence of mumps antibodies after 2 doses of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(4):552–60. doi: 10.1086/596207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeBaron CW, Forghani B, Matter L, et al. Persistence of Rubella Antibodies after 2 Doses of Measles-Mumps-Rubella Vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1086/605410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiebelkorn AP, Coleman LA, Belongia EA, et al. Mumps antibody response in young adults after a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albrecht P, Herrmann K, Burns GR. Role of virus strain in conventional and enhanced measles plaque neutralization test. J Virol Methods. 1981;3(5):251–60. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(81)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin WH, Vilalta A, Adams RJ, Rolland A, Sullivan SM, Griffin DE. Vaxfectin adjuvant improves antibody responses of juvenile rhesus macaques to a DNA vaccine encoding the measles virus hemagglutinin and fusion proteins. J Virol. 2013;87(12):6560–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercader S, Garcia P, Bellini WJ. Measles Virus IgG Avidity Assay for Use in Classification of Measles Vaccine Failure in Measles Elimination Settings. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2012;19(11):1810–7. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00406-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen RT, Markowitz LE, Albrecht P, et al. Measles antibody: reevaluation of protective titers. J Infect Dis. 1990;162(5):1036–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samb B, Aaby P, Whittle HC, et al. Serologic Status and Measles Attack Rates among Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Children in Rural Senegal. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 1995;14(3):203–9. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson JC, Hadler SC, Dykewicz CA, Reef S, Phillips L. Measles, mumps, and rubella--vaccine use and strategies for elimination of measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome and control of mumps: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-8):1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeung LF, Lurie P, Dayan G, et al. A limited measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated US boarding school. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1287–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitek CR, Aduddell M, Brinton MJ, Hoffman RE, Redd SC. Increased protections during a measles outbreak of children previously vaccinated with a second dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(7):620–3. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidkin I, Jokinen S, Broman M, Leinikki P, Peltola H. Persistence of measles, mumps, and rubella antibodies in an MMR-vaccinated cohort: a 20-year follow-up. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(7):950–6. doi: 10.1086/528993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidkin I, Valle M. Vaccine-induced measles virus antibodies after two doses of combined measles, mumps and rubella vaccine: a 12-year follow-up in two cohorts. Vaccine. 1998;16(20):2052–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen JB, Rota JS, Hickman CJ, et al. Outbreak of measles among persons with prior evidence of immunity, New York City, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(9):1205–10. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Schaid D, Moore SB, Jacobsen SJ. The association between HLA class I alleles and measles vaccine-induced antibody response: evidence of a significant association. Vaccine. 1998;16(19):1869–71. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Serres G, Boulianne N, Defay F, et al. Higher Risk of Measles when The First Dose of a Two-Dose Schedule is given at 12-14 Versus 15 Months of Age. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cid/cis439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickman CJ, Hyde TB, Sowers SB, et al. Laboratory characterization of measles virus infection in previously vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl 1):S549–58. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin WH, Griffin DE, Rota PA, et al. Successful respiratory immunization with dry powder live-attenuated measles virus vaccine in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):2987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017334108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong-Chew RM, Beeler JA, Audet S, Santos JI. Cellular and humoral immune responses to measles in immune adults re-immunized with measles vaccine. J Med Virol. 2003;70(2):276–80. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haralambieva IH, Ovsyannikova IG, O'Byrne M, Pankratz VS, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. A large observational study to concurrently assess persistence of measles specific B-cell and T-cell immunity in individuals following two doses of MMR vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29(27):4485–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen BJ, Parry RP, Doblas D, et al. Measles immunity testing: comparison of two measles IgG ELISAs with plaque reduction neutralisation assay. J Virol Methods. 2006;131(2):209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Flow chart for enrollment, analysis, and vaccination of subjects with a third dose of MMR vaccine.