Abstract

Objective

In the absence of an effective HIV vaccine, safer sexual practices are necessary to avert new infections. Therefore, we examined the efficacy of behavioral interventions to increase condom use and reduce sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV.

Design

Studies that examined a behavioral intervention focusing on reducing sexual risk, used a randomized controlled trial or a quasi-experimental design with a comparison condition, and provided needed information to calculate effect sizes for condom use and any type of STI, including HIV.

Methods

Studies were retrieved from electronic databases (e.g., PubMed, PsycINFO) and reference sections of relevant papers. Forty-two studies with 67 separate interventions (N = 40,665; M age = 26 years; 68% women; 59% Black) were included. Independent raters coded participant characteristics, design and methodological features, and intervention content. Weighted mean effect sizes, using both fixed-effects and random-effects models, were calculated. Potential moderators of intervention efficacy were assessed.

Results

Compared with controls, intervention participants increased their condom use [d+ = 0.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.04, 0.29; k = 67], had fewer incident STIs (d+ = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.04, 0.29; k = 62), including HIV (d+ = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.79; k = 13). Sample (e.g., ethnicity) and intervention features (e.g., skills training) moderated the efficacy of the intervention.

Conclusions

Behavioral interventions reduce sexual risk behavior and avert STIs and HIV. Translation and widespread dissemination of effective behavioral interventions are needed.

Keywords: behavior, condom, HIV/STI, meta-analysis, prevention, sex

INTRODUCTION

HIV remains a public health concern, with an estimated 2.6 million new infections occurring annually.1 Despite treatment advances, HIV presents significant health and social challenges.2 HIV is also costly, with medical care in the United States from the time of infection until the time of death estimated at $385,200.3 Global costs associated with antiretroviral therapy are estimated to be US $896 annually per person.4 In addition, new infections cost the US $29.7 billion annually in productivity losses.5 If incidence trends continue, the added annual cost of HIV care in the US will be between $128 and $237 billion dollars.6 To reduce the burden of HIV, prevention efforts need to be expanded.7 Identifying and evaluating successful behavioral interventions is critical to ensure that effective interventions are implemented with appropriate samples and in appropriate settings to achieve reductions in HIV transmission. To achieve this goal, meta-analytic techniques can help to quantitatively synthesize the behavioral intervention literature.

Meta-analyses of behavioral interventions have documented improvements in behavioral outcomes (e.g., condom use) among a number of groups (e.g., adolescents).8 Relatively fewer metaanalyses have examined biological outcomes, likely due to an insufficient number of studies measuring sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and/or HIV available to date. As a result, many of those metaanalyses have been underpowered.9–14 A recent meta-analysis found behavioral interventions improved both behavioral and biological out comes among clients at STI clinics in the United States.15 Although there was sufficient power to test incident STI (excluding HIV), this study was limited in that HIV incidence could be evaluated in only 5 of the 48 studies reviewed.15 Overall, it is unclear whether incident STIs, including HIV, are reduced after behavioral risk reduction interventions. Because condom use and incident STIs are independent outcomes,16 examining both behavioral and biological end points within a wider range of studies can increase our understanding of the efficacy of behavioral interventions.

The current study extends previous metaanalyses by focusing on the effects of behavioral interventions to improve both behavioral and biological outcomes. Specifically, meta analytic techniques were used to evaluate the efficacy of behavioral interventions to reduce incident STIs, including HIV, and to promote condom use. We hypothesize that those participants receiving a behavioral intervention targeting HIV prevention would increase their condom use and would be less likely to acquire STIs, including HIV, relative to controls.

We also examine the extent to which the efficacy of behavioral interventions was a function of participant or intervention characteristics. Moderators included the following: (A) gender, age, race, and sexual orientation; (B) baseline STI or HIV; (C) intervention content (motivation and/or skills training, addressing sociocultural barriers, providing condoms, and tailored or targeted content); (D) matching facilitators to participants (on gender or race), and (E) intervention length. We hypothesize that interventions will be more efficacious when they (A) sampled greater proportions of those who are most affected by HIV (women, young adults, Blacks, Latinos, MSM, and heterosexuals);1,17 (B) sampled patients diagnosed with an STI or HIV at baseline, as infected participants may be more motivated to decrease their risk behavior;18 (C) targeted motivation and provided skills training, consistent with motivational and skill-based theories of HIV prevention;19,20 (D) tailored content to the individual, targeted content toward a specific group (e.g., women), or matched facilitators to the gender or race of the participants, as tailoring and/or targeting the intervention content may enhance message relevancy;21 and (E) were longer, providing participants with additional opportunities to practice skills.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Study Selection

Studies were located using 3 strategies. First, electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, and other EBSCOhost databases) were searched using a Boolean search strategy for abbreviated (truncated words followed by an asterisk) and full keywords related to interventions that reported at least 1 laboratory tested incident STI: [(HIV OR STD OR STI OR (human AND immun* AND virus) OR (acquir* AND immun* AND syndrome) AND (sexual* AND transmit* AND disease) OR (sexual* AND transmit* AND infect*) OR Chancroid OR (Chlamydia AND Infect*) OR Conjunctivitis OR (Lympho granuloma and Venereum) OR Trachoma OR Gonorrhea OR (Granuloma AND Inguinale) OR Syphilis OR (Condylomata AND Acuminata) OR (Herpes AND Genitalis) OR (AIDS AND opportunistic AND infect*)] AND [(intervent* OR prevent*) AND (condom OR swab* OR sero*conver* OR (biological AND outcome)]. Second, we searched data bases and document archives of HIV-related interventions held by the National Institute of Mental Health–funded Syntheses of HIV/AIDS Risk Reduction Project (a database of HIV-related interventions, 1981 to present) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention Research Synthesis Project database. Finally, reference sections of obtained articles were examined.22 Studies fulfilling the selection criteria and available by July 2010 were included.

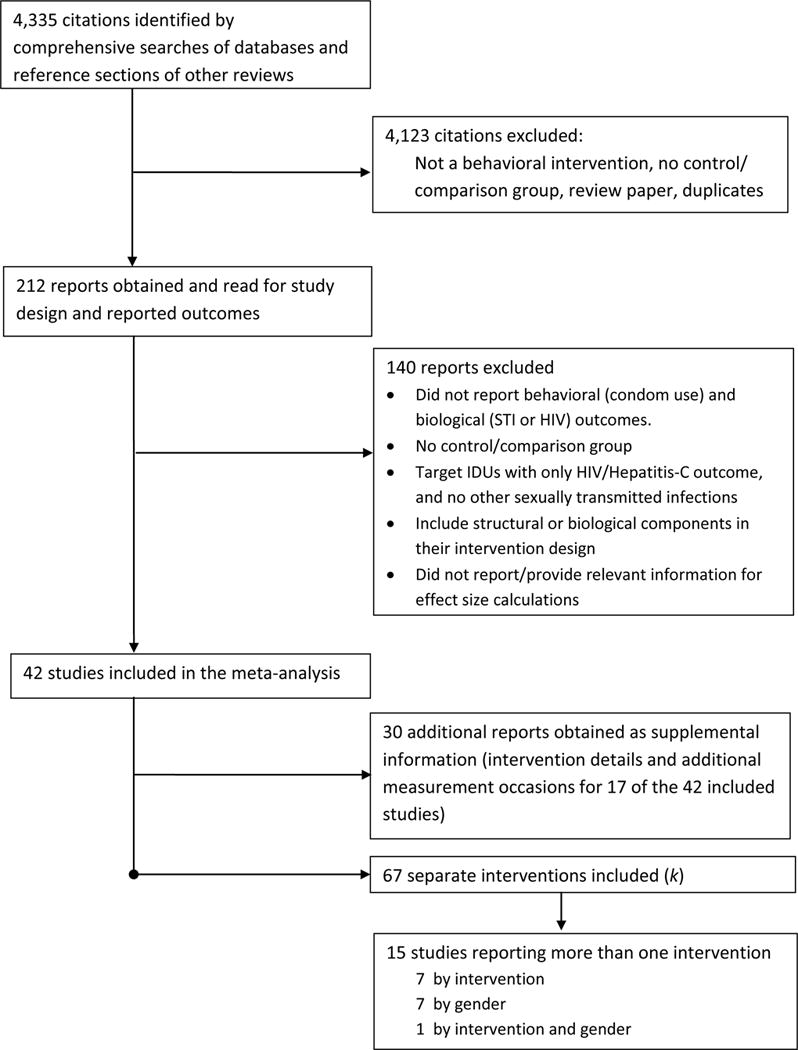

The selection process for study inclusion in the meta-analysis appears in Figure 1. Studies were included if they examined an HIV risk-reduction strategy, used a randomized controlled trial or a quasi-experimental design, assessed condom use and laboratory confirmed incident STIs, including HIV, and provided sufficient information to calculate effect sizes (ES). Studies were excluded if the intervention(s) did not focus on reducing the risk of HIV, had no comparison condition, or evaluated a structural-level (e.g., mass media) intervention. Of the initially relevant reports, 1 had insufficient information for the calculation of ES; the study authors did not respond to our request and the report was excluded. When multiple papers evaluated intervention efficacy with the same sample, we calculated ES for all the outcomes. Forty-two independent studies, including 67 separate interventions (k), met the selection criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.23–82

Figure 1.

Inclusion of HIV Prevention Studies with Behavioral and Biological Outcomes

Coding and Reliability

Three trained independent raters coded study information, sample characteristics (e.g., ethnicity, gender), design characteristics (e.g., recruitment method, number of follow ups), and content of control and intervention condition(s) (e.g., number of sessions). Study quality was assessed using 16 items (e.g., random assignment) from validated measures;83,84 scores ranged from 0 to 22. Interrater reliability for categorical variables was calculated as Cohen kappa (k).85 Mean k was 0.73 (median = 0.74), and the mean agreement was 83%, signifying high reliability. For continuous variables, we calculated an intra-class correlation; the mean effective reliability = 0.91, also high. Disagreements between coders were resolved through discussion.

Study Outcomes and Calculation of Effect Sizes

ES estimates for condom use and STIs, including HIV, were calculated. Trials varied in their measures of “condom use” (e.g., count vs. percent of condom-protected sexual events); thus, outcomes included protected or unprotected vaginal, anal, or unspecified intercourse across an array of contexts. Because the majority of the studies reported continuous measures, ES were defined as the mean difference between the treatment and control groups divided by the pooled standard deviation (d).86 In the absence of means and standard deviations, other statistical information (e.g., F values) was used.87,88 If a study reported dichotomous outcomes (e.g., frequencies), we calculated an odds ratio and transformed it to d using the Cox transformation.89 If no statistical information was available and the study reported a nonsignificant or significant between-group difference, we estimated that ES to be zero or calculated an ES based on the minimum statistically significant P value (i.e., P = 0.05), respectively.88 In calculating d, we (A) adjusted for baseline differences between condition(s) when preintervention measures were available;90 and (B) corrected for sample size bias.91 Positive ES indicated that treated participants increased condom use and reduced the incidence of STIs compared with controls.

Multiple ES were calculated from individual studies when they had more than 1 outcome, multiple intervention conditions, or when outcomes were separated by sample characteristics (e.g., gender). When a study contained multiple measures of the same outcome, the ES were averaged. ES calculated for each intervention and by sample characteristics were analyzed as separate studies.88 From the 42 studies that met the selection criteria, 67 interventions were analyzed. Of these 67, all measured self-reported condom use, 57 reported incident STIs, 8 reported incident HIV, and 5 reported both incident STIs and HIV, separately. If the study reported more than 1 follow-up, the last follow-up was used.

Statistical Analyses

Fixed-effect and random-effect analyses were con ducted in Stata 1192 using published macros.88 The homogeneity statistic, Q, determined whether each set of ESs shared a common ES; a significant Q indicates a lack of homogeneity and an inference of heterogeneity. To assess the extent to which studies’ outcomes were consistent, the I2 index and its corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated;93,94 I2 varies between 0 (homogeneous) and 100% (heterogeneous).95 If the confidence interval around I2 includes zero, the set of ES is considered homogeneous. Asymmetries in distributions of ES, which can suggest reporting bias, were examined with Begg technique,96 trim and fill,97 and Egger technique.98

To explain variability in ES, the relation between sample, methodological, or intervention characteristics and the magnitude of the effects were examined using a modified weighted least squares regression analyses with weights equivalent to the inverse of the variance for each ES.88,99 For the mixed-effect regression models, the inverse variance for each ES included both study-level sampling error and additional between-study population variance, following the restricted maximum likelihood solution; these models are more conservative than purely fixed-effects models.88 A priori determined moderators included sample characteristics (e.g., proportion women, age group), intervention content (e.g., motivation or behavioral skills), matching the facilitators with participants and intervention dose. Significant moderators were simultaneously entered into multiple regression models to evaluate whether they explained unique variance. Continuous variables (e.g., proportion Black, proportion Hispanic/ Latino) were mean centered to reduce multicolinearity. To retain all studies in multiple moderator models, missing values of significant moderators were imputed from the mean of other studies that reported the information.

RESULTS

Study, Sample, and Intervention Details

Descriptive features of the studies are provided in Table S1 (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/QAI/A223). Methodological quality of the studies ranged from 5 to 20 (median = 15). Publication year and methodological quality score were correlated (r = 0.52, P < 0.001); published ≥ 2003 received higher quality scores (median = 17) than earlier studies (median = 14).

Studies were conducted in North America (62%), Asia (17%), Africa (14%), Europe (5%), and South America (2%). Of the 40,665 participants sampled, 68% were women, 69% were Black, and their mean age was 26 years (SD = 7.62; range, 15%–44; 41% age 24 or younger). Several studies targeted women (50%) and Blacks and/or Hispanics (19%). Of the studies reporting alcohol (10 of 42) and/or drug use (14 of 42), 34% and 36% of participants reported current use of alcohol or illegal drugs, respectively. Twenty studies reported participants’ HIV status; most participants (80%) were HIV negative and 3 studies sampled only those with HIV.23–25 Of the 33 studies reporting STI status at baseline, many participants (42%) had a biologically confirmed STI (excluding HIV); 6 studies restricted their samples only to those with a current STI.26,27,100–103

Participants were typically assessed at a single follow up (M = 1.04; range = 1 to 2). The assessment typically occurred 13 weeks postintervention (M = 23.53; range = 0 – 208 weeks). When more than 1 follow-up was reported, we used the last assessment because biological outcomes tended to be reported at longer assessments. The last assessment typically occurred 52 weeks postintervention (M = 45.04; SD = 29.98). Most participants (79%) were offered incentives (e.g., money) for participating in the research and/or completing the assessment(s).

Most studies (83%) randomly assigned individuals or groups to conditions. The control condition was most often HIV education (48%), but 38% used an active comparison condition (e.g., brief form of intervention), and 14% used an assessment-only control. Interventions involved face-to-face delivery to a group (45%), an individual (45%), or a combination (10%). Group interventions met for a median of 4 sessions of 120 minutes each with a median of 2 facilitators and 10 participants per session; individual interventions met for a median of 1 session of 39 minutes each with 1 facilitator. Most interventions provided education (90%). Most interventions (84%) addressed proximal (e.g., risk awareness, decisional balance exercises, and attitudes toward risk reduction) motivation, whereas 46% addressed distal (e.g., life goals, personal values) motivational components.19 Many provided skills training (i.e., with rehearsal and feedback) relating to intrapersonal (e.g., self-management; 58%), interpersonal (e.g., partner negotiation; 55%), and/or condom-specific (e.g., placing condoms on model; 43%) aspects of risk reduction. Condoms were provided in 39% of the interventions. Most interventions (94%) included counseling and testing. Boosters were provided in 46% of the interventions. In 66% of the interventions, formative research was used to target intervention content to the sample. Facilitators were often paraprofessionals (85%); some interventions reported matching the facilitators to the ethnicity (28%) or gender (45%) of the sample.

Overall Efficacy of the Interventions

Table 1 provides the weighted mean ES for the 42 studies (k = 67) at the final postintervention assessment. Over all, analyses indicate that behavioral interventions improved condom use and reduced incident STIs and HIV compared with controls. By the final assessment, intervention participants significantly increased their condom use (d+ = 0.17) and reduced their incidence of STIs (d+ = 0.16), including HIV (d+ = 0.46), compared with controls. The pattern of results was consistent using fixed-effect or random-effect assumptions. There were no asymmetries that might be interpreted as publication bias: Trim and fill results for each outcome suggested that no study was missing; Begg test96 results were nonsignificant (zcondom use = 1.15, P = 0.25; zSTI = 0.53, P = 0.60; zHIV = 0.37, P = 0.71) as were Egger’s test38 results (biascondom use = 0.31, t = 0.65, P = 0.52; biasSTI = 0.94, t = 1.14, P = 0.26; biasHIV = 0.091, t = 0.030, P = 0.98).

Table 1.

Weighted mean effect sizes and homogeneity statistics for outcomes at the final post-intervention assessment.

| Outcome | k |

d+ (95% CI)

|

Homogeneity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | Random effects | Q | P | I2 index (95% CI) | ||

| Condom use | 67 | 0.12 (0.10, 0.14) | 0.17 (0.04, 0.29) | 1169.77 | <.001 | 94% (93, 95) |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 62 | 0.17 (0.14, 0.19) | 0.16 (0.04, 0.29) | 632.95 | <.001 | 90% (88, 92) |

| HIV | 13 | 0.19 (0.15, 0.23) | 0.46 (0.13, 0.79) | 1025.31 | <.001 | 99% (99, 99) |

Note. k, number of interventions. d+, weighted mean effect size. CI, confidence interval.

The hypothesis of homogeneity was rejected for each outcome; examination of I2 confirmed high levels of heterogeneity. Moderator tests examined whether a priori determined sample or intervention characteristics related to the variability in ES (reported below; Table 2 for specific moderators). Analyses with and without moderator imputation revealed the same patterns; therefore, only the analyses with imputation appear.

Table 2.

Moderators of condom use, incident STIs, and HIV at the final assessment interval*

| Moderators | Condom Use | Incident STIs | Incident HIV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | P | k | β | P | k | β | P | k | |

| Sample Characteristics | |||||||||

| Women (%) | 0.23 | .09 | 67 | 0.17 | .27 | 62 | 0.11 | .57 | 13 |

| Age group (≤24 years) | −0.23 | .09 | 67 | −0.07 | .65 | 62 | −0.04 | .81 | 13 |

| Blacks (%) | 0.07 | .61 | 61 | 0.15 | .34 | 56 | −0.61 | .00 | 12 |

| Latino (%) | −0.04 | .77 | 44 | −0.11 | .59 | 39 | 0.98 | .00 | 10 |

| MSM (%) | −0.05 | .74 | 40 | −0.28 | .22 | 37 | −0.24 | .38 | 5 |

| Heterosexual (%) | 0.11 | .51 | 38 | 0.35 | .16 | 35 | 0.24 | .38 | 5 |

| STI or HIV diagnosed at baseline | 0.09 | .50 | 67 | 0.32 | .04 | 62 | – | – | 13 |

| Intervention Characteristics | |||||||||

| Motivation, proximal | −0.24 | .08 | 67 | 0.06 | .72 | 62 | 0.23 | .22 | 13 |

| Motivation, distal | 0.13 | .35 | 67 | 0.21 | .18 | 62 | 0.43 | .02 | 13 |

| Condom skills, active | 0.02 | .90 | 67 | −0.16 | .31 | 62 | 0.51 | .01 | 13 |

| Interpersonal skills, active | 0.03 | .80 | 67 | −0.13 | .39 | 62 | 0.43 | .02 | 13 |

| Self-management skills, active | −0.28 | .04 | 67 | −0.35 | .03 | 62 | −0.15 | .43 | 13 |

| Socio-cultural barriers addressed | 0.32 | .02 | 67 | 0.01 | .93 | 62 | 0.11 | .55 | 13 |

| Provided condoms | −0.06 | .68 | 67 | −0.34 | .03 | 62 | −0.43 | .02 | 13 |

| Tailored | −0.22 | .11 | 67 | −0.05 | .73 | 62 | 0.09 | .65 | 13 |

| Targeted, women | 0.22 | .10 | 67 | 0.26 | .09 | 62 | 0.45 | .02 | 13 |

| Targeted, Blacks or Hispanic/Latino | 0.32 | .02 | 67 | 0.23 | .13 | 62 | – | – | 13 |

| Matched facilitator by gender | 0.12 | .37 | 67 | 0.15 | .34 | 62 | 0.20 | .29 | 13 |

| Matched facilitator by race | 0.26 | .06 | 67 | 0.15 | .35 | 62 | – | – | 13 |

| Total dose | 0.01 | .96 | 63 | 0.04 | .79 | 58 | −0.25 | .19 | 12 |

Models used the inverse of the variance for each effect size as weights; reported coefficients (β) are standardized. k = number of studies. Bold typeface values are significant at P ≤.05 level. Potential moderators with missing values indicate all observations contained identical values.

Moderators of Intervention Impact on Condom Use

Bivariate regression analyses under mixed-effect assumptions examined potential moderators of condom use. As shown in Table 2, interventions increased participant’s condom use when the content of the intervention excluded self-management skills-training (β = −0.28, P = .04), addressed sociocultural barriers (β = 0.31, P = .03), and the intervention targeted Blacks and/or Hispanics (β = 0.32, P = .02). When significant bivariate moderators were simultaneously entered into a regression model, addressing sociocultural barriers was the only variable that remained a significant moderator of condom use (β = 0.31, P =.03).

Moderators of Intervention Impact on Sexually Transmitted Infections

As Table 2 shows, intervention participants succeeded in reducing incident STIs when sample participants diagnosed with an STI, including HIV, at baseline (β = 0.32, P = .04), the intervention excluded self-management skills training (β = −0.35, P = .03), and when condoms were not provided (β = −0.34, P = .03). When entered simultaneously, only STI/HIV diagnosed at baseline (β = 0.31, P = .04) and self-management skills training (β = −0.32, P = .04) remained significant moderators of incident STIs and accounted for 32% of the variance.

Moderators of the Intervention Impact on Incident HIV

Moderator tests for the intervention impact on incident HIV appear in Table 2. HIV incidence was reduced when studies sampled fewer Blacks or more Hispanic/Latinos, intervention content included a distal motivational component, condom skills training, active interpersonal skills training, did not provide condoms, and was targeted to women. When entered simultaneously in a regression model, only proportion of Hispanic/Latino participants remained significant; thus, interventions were successful in reducing the incidence of HIV when sampling more Hispanic/Latino participants (β = 0.88, P < .01).

DISCUSSION

Results from the current meta-analysis of 42 studies evaluating 67 interventions and measuring both behavioral and biological outcomes demonstrated that behavioral interventions increase condom use and lower the incidence of STIs, including HIV, for durations up to 4 years. Although research indicates that between-group ES are generally smaller, especially when comparing an intervention to an active control,104 weighted mean ES in the current meta-analysis were of small to medium magnitude (0.16 to 0.46). To our knowledge, this meta-analytic review is the first to examine the incidence of HIV in a wide range of populations at risk for HIV. Contrary to recent reports,105 these findings show that behavioral interventions reduce behavioral risk and incident infections in a wide range of samples.

Several sample and intervention characteristics moderated intervention efficacy. First, interventions were more successful at improving condom use when sociocultural barriers of safer sex were addressed. Because several social, cultural, and economic factors influence condom use,106 and because poverty, gender inequality, and stigma influence individual’s risk for HIV, this result is not surprising.107 Other life challenges often overshadow HIV as a concern, with survival needs forcing people into riskier practices and relationships. Results from this meta-analysis suggest that addressing sociocultural barriers within interventions seems to make them more efficacious at reducing sexual risk.

Second, contrary to expectations, providing participants with active self-management training was less successful in improving condom use and incident STIs at the final assessment. In our prior meta-analytic review,108 interventions were successful at improving condom use at “short term” (less than 3 months postintervention), but not at “long-term” (.52 weeks), when self-management skills training was provided. In the current meta-analysis, the last assessment typically occurred at 52 weeks postintervention. One possible explanation for our findings is that self-management skills learned during the intervention were not sustained 1 year later. Active self-management training may dissipate over time; to improve sustainability, participants may benefit from boosters targeting self-management skills.

Third, consistent with expectations, interventions were diagnosed with an STI or HIV at study entry. Prior research examining the effects of STI diagnosis “alone” has found little change in sexual risk behavior compared with individuals not diagnosed with an STI.109,110 Consistent with this research, a diagnosis of an STI or HIV was not a significant moderator of condom use in our meta-analysis. In contrast, an STI or HIV diagnosis at baseline was the sole moderator of incident STIs in our multiple moderator analyses. Being diagnosed and receiving treatment for an STI before a behavioral HIV intervention may increase receptivity to the intervention thus behavioral changes (e.g., partner reduction, monogamy) and reducing STI incidence. Moreover, research indicates that the association between STIs and condom use varies by type of infection, and increasing condom use may not avert all STIs equally.16 Future research might examine the contexts in which STI diagnosis moderates both behavioral and biological outcomes.

Finally, interventions were more successful at reducing the incidence of HIV when sampling more Latinos. Globally, Latinos are disproportionately affected by HIV.7 Interventions targeting Latinos are urgently needed to avert HIV infections among this group. Our meta-analysis shows that interventions reduced incidence of HIV in samples with greater proportions of Latino participants. In an earlier review, Noguchi et al. found that sampling greater proportions of Latinos was related to acceptance and retention of HIV prevention programs.111 Acceptance and retention of an intervention has the potential to increase participants’ exposure to targeted content. Thus, one potential explanation for these findings is that exposure to targeted intervention content increases the relevancy of the message, thereby facilitating behavioral change and ultimately reducing the incidence of HIV.21 Consistent with prior meta-analytic reviews, the current findings suggest that interventionists developing behavioral interventions to reduce HIV should conduct formative research to identify the specific needs of Latinos.9,112

Because the ultimate goal of most behavioral interventions is to reduce the transmission of HIV, measuring HIV incidence is a desirable but rarely feasible outcome.113 Given the low incidence of HIV in many populations, testing for HIV is often impractical as large sample sizes would be required to detect a statistically significant effect of the behavioral intervention.16 Therefore, most behavioral intervention trials use self-reported behaviors and STIs as proxy measures of the impact of an intervention on the incidence of HIV within a given subpopulation. Although prior research indicates that improvements in self-reported behaviors and incident STIs after exposure to a behavioral intervention, these findings should not imply that the same intervention was also successful in reducing HIV incidence.16 In the current meta-analysis, we show that behavioral interventions are successful both at use and at reducing incident STIs and HIV. Although it may seem that changes in behavioral outcomes resulted in changes in biological outcomes, exploratory analyses do not support that assertion. In fact, there was no association between condom use, incident STIs, and HIV (Ps ≥ .10). Weighted regression analyses predicting incident HIV from condom use and incident STIs indicated that more successful at lowering incident STIs with patients behavioral (β = −0.11, P = .56, k = 13) and biological (β = −0.03, P = .89, k = 8) outcomes are not associated with changes in HIV incidence. Moreover, simply providing condoms to individuals was insufficient in reducing the incidence of STIs, as shown in our moderator analyses. These findings warrant further investigation as the current meta-analysis was limited in the number of studies available to test the behavioral– biological association. The association between behavioral and biological outcomes is complex. Transmission of STIs depends upon several factors including partner type, characteristics, and perceptions of partner safety.113 Thus, examining both behavioral and biological outcomes, and factors associated with sexual risk behaviors, should be important in determining the efficacy of behavioral interventions.

LIMITATIONS

Limitations of the underlying literature should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, self-reports are vulnerable to cognitive and social biases.114,115 Nonetheless, most researchers employed methods designed to optimize data quality.16 Second, follow-ups typically rely on a single assessment, which may not be representative of long-term ongoing risk. Still, the data do provide support for long-term efficacy of behavioral interventions given that the studies’ last assessment occurred ≥1 year post-intervention. Third, variations in how condom use was measured (e.g., frequency, proportions) and STIs (e.g., use of composite measures) required that we employ heterogeneous markers of risk reduction that are rarely partner specific. Fourth, the diversity of samples may have obscured nuanced patterns in the study outcomes. Fifth, most studies were conducted in the U.S.; it was not feasible to examine how well findings generalize across other important geographical regions of the world. Finally, only a few studies (6 studies, see Table S1, Supple mental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/QAI/A223) used a waitlist/no treatment/assessment-only control group, which precluded an evaluation of the impact of behavioral interventions relative to type of control group (e.g., no treatment vs. active comparisons).

CONCLUSIONS

Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV among studies measuring both behavioral and biological outcomes are successful at improving condom use and reducing incident STIs, including HIV, with effects that persist for durations as long as 4 years. Because the association between behavioral and biological outcomes is complex,113 measuring both behavioral and biological outcomes can help to determine the efficacy of behavioral interventions. Implementation of efficacious behavioral interventions within a wide range of population groups should be a high priority.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the study authors who provided additional intervention details or data for this investigation and the other SHARP (Synthesis of HIV/AIDS Research Project) team members who contributed to the development of this paper.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by NIH grants R01MH58563 and K18AI094581 to Blair T. Johnson.

Footnotes

Please note: Effective August 1, 2011, Drs. Scott-Sheldon and Carey will be at the Center for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, Coro Building, Suite 314, One Hoppin Street, Providence, RI 02903.

Author Contributions:

Authors contributed to the manuscript in the following manner:

Study concept and design: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, Warren, Johnson, Carey

Acquisition of data: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, Warren

Analysis and interpretation of data: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, Warren, Johnson, Carey

Drafting of the manuscript: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, Warren

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, Warren, Johnson, Carey

Statistical analysis: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina

Obtaining funding: Johnson, Carey

Administrative, technical, or material support: Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, Warren

Study supervision: Johnson, Carey

Access to Data: Drs. Scott-Sheldon and Huedo-Medina had full access to all the data and share responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of interest: The authors indicate no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2010 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm Accessed July 15, 2011.

- 2.Antoni MH. Stress, coping, and health in HIV/AIDS. In: Folkman S, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 428–451. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schackman BR, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, et al. The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States. Med Care. 2006;44:990–997. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228021.89490.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzies NA, Berruti AA, Berzon R, et al. The cost of providing comprehensive HIV treatment in PEPFAR supported programs. AIDS. 2011;25:1753–1760. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283463eec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchinson AB, Farnham PG, Dean HD, et al. The economic burden of HIV in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: evidence of continuing racial and ethnic differences. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:451–457. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243090.32866.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall HI, Green TA, Wolitski RJ, et al. Estimated future HIV prevalence, incidence, and potential infections averted in the United States: a multiple scenario analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:271–276. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e8f90c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF. Progress Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noar SM. Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behavior: review and synthesis of meta-analytic evidence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:335–353. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, et al. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American females in the United States: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann MS, Johnson WD, Semaan S, et al. Review and meta-analysis of HIV prevention intervention research for heterosexual adult populations in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(suppl 1):S106–S117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward DJ, Rowe B, Pattison H, et al. Reducing the risk of sexually transmitted infections in genitourinary medicine clinic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioural interventions. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:386–393. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crepaz N, Horn AK, Rama SM, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually trans mitted disease in black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: a meta-analytic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:319–332. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000240342.12960.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20:143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott-Sheldon LA, Fielder RL, Carey MP. Sexual risk reduction interventions for patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States: a meta-analytic review, 1986 to early 2009. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:191–204. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishbein M, Pequegnat W. Evaluating AIDS prevention interventions using behavioral and biological outcome measures. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:101–110. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/index.htm Accessed February 2011.

- 18.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, et al. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 19851997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carey MP, Lewis BP. Motivational strategies can augment HIV-risk reduction programs. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:269–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1025429216459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Shuper PA. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of HIV prevention behavior. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 21–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(suppl 3):S227–S232. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal R. The “filedrawer” problem and tolerance for null results. Psyc Bull. 1979;86:638–641. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saleh-Onoya D, Reddy PS, Ruiter RAC, et al. Condom use promotion among isiXhosa speaking women living with HIV in the Western Cape Province, South Africa: a pilot study. AIDS Care. 2009;21:817–825. doi: 10.1080/09540120802537823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, et al. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: The WiLLOW Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(suppl 2):S58–S67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolitski RJ, Parsons JT, Gomez CA, et al. Prevention with gay and bisexual men living with HIV: rationale and methods of the Seropositive Urban Men’s Intervention Trial (SUMIT) AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 1):S1–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167347.77632.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crosby R, DiClemente RJ, Charnigo R, et al. A brief, clinic-based, safer sex intervention for heterosexual African American men newly diagnosed with an STD: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 1):S96–S103. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shain RN, Piper JM, Newton ER, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:93–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Archibald CP, Chan RK, Wong ML, et al. Evaluation of a safe-sex intervention programme among sex workers in Singapore. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:268–272. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan RK, Goh A, Goh CL, et al. “Project Protect”–an STD/AIDS prevention intervention programme for sex workers and establishments in Singapore. Paper presented at: International Conference AIDS; June 6 11, 1993; Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhave G, Lindan C, Hudes E, et al. Impact of an intervention on HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and condom use among sex workers in Bombay, India. AIDS. 1995;9:S21–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyer C, Barrett D, Peterman T, et al. Sexually transmitted disease (STD) and HIV risk in heterosexual adults attending a public STD clinic: evaluation of a randomized controlled behavioral risk-reduction intervention trial. AIDS. 1997;11:359–367. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Shaffer RA, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive behavioral, group, randomized controlled intervention trial to prevent sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies in young women. Prev Med. 2005;40:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benner TA. FOCUS: preventing sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies among young women. In: Card JJ, Benner TA, editors. Model Programs for Adolescent Sexual Health: Evidence-Based HIV, STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Interventions. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Pollack LM, et al. Sociodemographic markers and behavioral correlates of sexually transmitted infections in a nonclinical sample of adolescent and young adult women. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:307–315. doi: 10.1086/506328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang LY, Shafer MA, Pollack LM, et al. Sexual behaviors after universal screening of sexually transmitted infections in healthy young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:105–113. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000247643.17067.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brems C, Dewane SL, Johnson ME, et al. Brief motivational interventions for HIV/STI risk reduction among individuals receiving alcohol detoxification. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:397–414. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carey MP, Senn TE, Vanable PA, et al. Brief and intensive behavioral interventions to promote sexual risk reduction among STD clinic patients: results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:504–517. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9587-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chacko MR, Wiemann CM, Kozinetz CA, et al. Efficacy of a motivational behavioral intervention to promote chlamydia and gonorrhea screening in young women: a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention program among female adolescents experiencing gender based violence. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1085–1090. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wingood G, Sales J, Braxton N, et al. The handbook of prevention and intervention programs for adolescent girls. In: Lecroy C, Mann J, editors. Behavioural Case Formulation and Intervention: A Functional Analytical Approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- 42.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES, et al. Efficacy of sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk-reduction intervention for African-American adolescent females seeking sexual health services: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1112–1121. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Downs JS, Murray PJ, Bruine de Bruin W, et al. Interactive video behavioral intervention to reduce adolescent females’ STD risk: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ford K, Wirawan DN, Reed BD, et al. The Bali STD/AIDS Study: evaluation of an intervention for sex workers. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:50–58. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ford K, Reed BD, Wirawan DN, et al. The Bali STD/AIDS study: human papillomavirus infection among female sex workers. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:681–687. doi: 10.1258/095646203322387947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimley DM, Hook EW., III A 15minute interactive, computerized condom use intervention with biological endpoints. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:73–78. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818eea81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadden BR. An HIV/AIDS prevention intervention with female and male STD patients in a peri urban settlement in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: University of Natal; 1997. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hobfoll SE, Jackson AP, Lavin J, et al. Effects and generalizability of communally oriented HIVAIDS prevention versus general health pro motion groups for single, inner city women in urban clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:950–960. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imrie J, Stephenson JM, Cowan FM, et al. A cognitive behavioural intervention to reduce sexually transmitted infections among gay men: randomised trial. BMJ. 2001;322:1451–1456. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.James NJ, Gillies PA, Bignell CJ. Evaluation of a randomized controlled trial of HIV and sexually transmitted disease prevention in a genitourinary medicine clinic setting. AIDS. 1998;12:1235–1242. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199810000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, III, O’Leary A. Effects on sexual risk behavior and STD rate of brief HIV/STD prevention interventions for African American women in primary care settings. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1034–1040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Leary A, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB. Mediation analysis of an effective sexual risk reduction intervention for women: the importance of self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2 suppl):S180–S184. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, et al. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 159:440–449. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. 005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:A506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, et al. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychol. 2005;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficency virus and sexually transmitted diseases. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gottlieb SL, Douglas JM, Jr, Foster M, et al. Incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in 5 sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics and the effect of HIV/STD risk-reduction counseling. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1059–1067. doi: 10.1086/423323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Metcalf CA, Malotte CK, Douglas JM, Jr, et al. Efficacy of a booster counseling session 6 months after HIV testing and counseling: a randomized, controlled trial (RESPECT2) Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151420.92624.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warner L, Newman DR, Kamb ML, et al. Problems with condom use among patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics: prevalence, predictors, and relation to incident gonorrhea and chlamydia. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:341–349. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kershaw TS, Magriples U, Westdahl C, et al. Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2079–2086. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T. Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2004;364:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li X, Wang B, Fang X, et al. Short-term effect of a cultural adaptation of voluntary counseling and testing among female sex workers in China: a quasi-experimental trial. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:406–419. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mhalu F, Hirji K, Ijumba P, et al. A cross-sectional study of a program for HIV infection control among public house workers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:290–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.NIMH. The NIMH multisite HIV prevention trial: reducing HIV sexual risk behavior. Science. 1998;280:1889–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orr DP, Langefeld CD, Katz BP, et al. Behavioral intervention to increase condom use among high-risk female adolescents. J Pediatr. 1996;128:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patterson TL, Mausbach B, Lozada R, et al. Efficacy of a brief behavioral intervention to promote condom use among female sex workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:2051–2057. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patterson TL, Orozovich P, Semple SJ, et al. A sexual risk reduction intervention for female sex workers in Mexico: design and baseline characteristics. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2006;5:115–137. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Fraga M, et al. An HIVprevention intervention for sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico: A pilot study. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2005;27:82–100. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peipert JF, Redding CA, Blume JD, et al. Tailored intervention to increase dual contraceptive method use: a randomized trial to reduce un intended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:630 E631–E638. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rekart ML, Wong T, Wong E, et al. The impact of syphilis mass treatment one year later: self-reported behaviour change among participants. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:571–578. doi: 10.1258/0956462054679179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roye C, Silverman PP, Krauss B. A brief, low-cost, theory-based intervention to promote dual method use by black and Latina female adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:608–621. doi: 10.1177/1090198105284840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Champion JD, Shain RN, Korte JE, et al. Behavioral interventions and abuse: secondary analysis of reinfection in minority women. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:748–753. doi: 10.1258/095646207782212180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sherman SG, Sutcliffe C, Srirojn B, et al. Evaluation of a peer network intervention trial among young methamphetamine users in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The Voluntary HIV1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group. Efficacy of voluntary HIV1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson TE, Hogben M, Malka ES, et al. A randomized controlled trial for reducing risks for sexually transmitted infections through enhanced patient-based partner notification. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 1):S104–S110. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolitski RJ, Gomez CA, Parsons JT. Effects of a peer-led behavioral intervention to reduce HIV transmission and promote sero-status disclosure among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 1):S99–S109. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167356.94664.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wong ML, Chan R, Lee J, et al. Controlled evaluation of a behavioral intervention programme on condom use and gonorrhoea incidence among sex workers in Singapore. Health Educ Res. 1996;11:423–432. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bishop GD, Wong ML. Designing sustainable health promotion: STD and HIV prevention in Singapore. In: MacLachlan M, editor. Cultivating Health: Cultural Perspectives on Promoting Health. New York, NY: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wong ML, Chan KW, Koh D. A sustainable behavioral intervention to increase condom use and reduce gonorrhea among sex workers in Singapore: 2year follow-up. Prev Med. 1998;27:891–900. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong ML, Chan R, Koh D. Long-term effects of condom promotion programmes for vaginal and oral sex on sexually transmitted infections among sex workers in Singapore. AIDS. 2004;18:1195–1199. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wong ML, Chan R, Koh D, et al. Theory and action for effective condom promotion: illustrations from a behavior intervention project for sex workers in Singapore. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1994;15:405–421. doi: 10.2190/C8A0-VNCH-MNEB-H6AV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wynendaele B, Bobma W, Manga W, et al. Impact of counselling on safer sex and STD occurrence among STD patients in Malawi. Int J STD AIDS. 1995;6:105–109. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miller WR, Brown JM, Simpson TL, et al. What works? A methodological analysis of the alcohol treatment outcome literature. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternatives. 2nd. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. pp. 12–44. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd. New York, NY: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson BT, Eagly AH. Quantitative synthesis of social psychological research. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 496–528. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Chacon-Moscoso S. Effect size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2003;8:448–467. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1988;41:257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6:107–128. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stata Statistical Software: Release 11 [computer program] College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychological Methods. 2006;11:193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in metaanalyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hedges LV. Fixed effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hadden BR. An HIV/AIDS prevention intervention with female and male STD patients in a peri-urban settlement in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Orr DP, Langefeld CD, Katz BP, et al. Behavioral intervention to increase condom use among high-risk female adolescents. J Pediatr. 1996;128:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wilton L, Herbst JH, Coury-Doniger P, et al. Efficacy of an HIV/STI prevention intervention for black men who have sex with men: findings from the Many Men, Many Voices (3MV) project. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:532–544. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wynendaele B, Bomba W, M’Manga W, et al. Impact of counselling on safer sex and STD occurrence among STD patients in Malawi. Int J STD AIDS. 1995;6:105–109. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Grissom RJ. The magical number .7 +/ .2: meta-meta-analysis of the probability of superior outcome in comparisons involving therapy, placebo, and control. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:973–982. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Padian NS, McCoy SI, Balkus JE, et al. Weighing the gold in the gold standard: challenges in HIV prevention research. AIDS. 2010;24:621–635. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337798a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sarkar NN. Barriers to condom use. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13:114–122. doi: 10.1080/13625180802011302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Johnson BT, Redding CA, DiClemente RJ, et al. A network-individual resource model for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(suppl 2):204–221. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, et al. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR, Lewis JB, et al. Sexual risk following a sexually transmitted disease diagnosis: the more things change the more they stay the same. J Behav Med. 2004;27:445–461. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000047609.75395.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wilson TE, Jaccard J, Levinson RA, et al. Testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: implications for risk behavior in women. Health Psychol. 1996;15:252–260. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Noguchi K, Albarracin D, Durantini MR, et al. Who participates in which health promotion programs? A meta-analysis of motivations underlying enrollment and retention in HIV-prevention interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:955–975. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, et al. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995–2008: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pequegnat W, Fishbein M, Celentano D, et al. NIMH/APPC workgroup on behavioral and biological outcomes in HIV/STD prevention studies: a position statement. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:127–132. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Weinhardt LS, Forsyth AD, Carey MP, et al. Reliability and validity of self-report measures of HIV-related sexual behavior: progress since 1990 and recommendations for research and practice. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27:155–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1018682530519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.