Abstract

Objective

To address clinical uncertainties about the effectiveness and safety of long-term antibiotic therapy for preventing recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults.

Design

Systematic review andmeta-analysis of randomised trials.

Method

We searched Medline, Embase, The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature(CINAHL), and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials from inception to August 2016. Eligible studies compared long-term antibiotic therapy with non-antibiotic therapy or placebo in men or women aged over 65, or in postmenopausal women, with recurrent UTIs.

Results

We did not identify any studies that included older men. Three randomised controlled trials compared long-term antibiotics with vaginal oestrogens (n=150), oral lactobacilli (n=238) and D-mannose powder (n=94) in postmenopausal women. Long-term antibiotics reduced the risk of UTI recurrence by 24% (three trials, n=482; pooled risk ratio (RR) 0.76; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.95, number needed to treat=8.5). There was no statistically significant increase in risk of adverse events (mild adverse events: pooled RR 1.52; 95% CI 0.76 to 3.03; serious adverse events: pooled RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.66). One trial showed 90% of urinary and faecal Escherichia coli isolates were resistant to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole after 1 month of prophylaxis.

Conclusions

Findings from three small trials with relatively short follow-up periods suggest long-term antibiotic therapy reduces the risk of recurrence in postmenopausal women with recurrent UTI. We did not identify any evidence to inform several clinically important scenarios including, benefits and harms in older men or frail care home residents, optimal duration of prophylaxis, recurrence rates once prophylaxis stops and effects on urinary antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: Urinary tract infections, Antibiotic prophylaxis, Antibiotic resistance

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Recurrent urinary tract infection is one of the most common reasons for long-term antibiotic use in the frail elderly. We systematically reviewed trial evidence to address clinical uncertainties around this practice.

We did not identify any trials in older men nor any trials in frail care home residents.

We identified only three small European trials, with follow-up ranging from 6 to 15 months, in older women.

Only one trial measured the impact of long-term antibiotics on antibiotic resistance.

Trial evidence suggests long-term antibiotics reduce the risk of UTI recurrence in older women. Many clinical uncertainties remain unaddressed.

Introduction

Older men and women are commonly prescribed long-term antibiotics to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI).1 2 Antibiotic use is a key driver of antibiotic resistance.3 Therefore, antibiotic use must be justified by robust evidence, where the estimated benefit outweighs estimated harm.

UTIs, and consequently recurrent UTIs, are overdiagnosed in older people.4 5 Therefore, antibiotic prophylaxis may actually be prescribed for symptoms that represent bladder dysfunction or localised vaginal symptoms rather than true UTI, and thus will not confer the intended benefit. Multimorbidity, frailty and polypharmacy are more common in older people and are contributory factors for potential harms such as those related to drug interactions. For example, older adults coprescribed renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and trimethoprim-containing antibiotics were shown to be at increased risk of hyperkalaemia-related hospitalisation6 and sudden death.7

Previous meta-analyses showed antibiotic prophylaxis conferred a relative risk reduction of 79% in the proportion of women experiencing a microbiologically confirmed UTI, compared with placebo.8 However, these analyses included data from mostly small trials of younger women without comorbidities. There is uncertainty around the generalisability of these findings to older adults.

There are several important clinical uncertainties relating to long-term antibiotic use in older adults with recurrent UTI, including effect on frequency of infective episodes, optimal duration of prophylaxis, adverse effects, risk of relapse following cessation of prophylaxis and effect on urinary antibiotic resistance. We therefore systematically reviewed randomised controlled trials comparing long-term antibiotic prophylaxis with placebo or non-antibiotic therapy for preventing further episodes of UTI in older people. Our main objective was to quantify the benefits and harms of long-term antibiotics for older adults, to better inform patients and clinicians during clinical decision making.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review following guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for conduct and PRISMA guidelines (see online supplementary file PRISMA checklist) for reporting.9 The review protocol was prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015016628; registration number: PROSPERO 2015:CRD42015016628).

bmjopen-2016-015233supp002.doc (66.5KB, doc)

Data sources

We systematically searched Medline, Embase, CINAHL and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to March 2016 for English language randomised controlled trials. Our search strategy consisted of keywords and medical subject headings terms for urinary tract infection and randomised trials (see online supplementary appendix 1).

bmjopen-2016-015233supp001.pdf (48.1KB, pdf)

One author (HA) conducted the first screening of potentially relevant records based on titles and abstracts, and two authors (HA and FD) independently performed the final selection of included trials based on full-text evaluation. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were screened for further potentially relevant studies. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Study selection

We included only randomised controlled trials published in full (ie, not abstracts) in English, comparing the effect of long-term antibiotics versus placebo or non-antibiotic interventions on the rate of UTI in older adults with recurrent UTI. We defined ‘long-term antibiotics’ as daily antibiotic dosing for at least 6 months, ‘older adults’ as women who were postmenopausal or over the age of 65 and men aged over 65 and ‘recurrent UTI’ as self-reported or clinically recorded history of two or more UTIs in 6 months or three or more in 12 months.

We included studies recruiting adults of all ages and screened relevant results to assess whether reported data allowed estimates of effect size in our specified population of older adults. For data not presented in this format, we contacted authors if the study was published in the last 10 years and if the mean or median age in any arm was greater than 50 years.

We excluded studies evaluating the effect of prophylactic antibiotics in specific situations, for example, post catheterisation, postsurgery, in patients with spinal injuries or in those with structural renal tract abnormalities.

Outcome measures

Our primary outcome was the number of UTI recurrences per patient-year during the prophylaxis period, defined microbiologically (>100 000 colony-forming units of bacteria/mL of urine) and/or clinically (for example, dysuria, polyuria, loin pain, fever) or other measure of change in the frequency of UTI events during prophylaxis. We also aimed to assess the proportion of patients with severe (requiring withdrawal of treatment) and mild (not requiring withdrawal of treatment) adverse effects. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence after the prophylaxis period, time to first recurrence, proportion of patients with antibiotic resistant micro-organisms in future urine samples and quality of life.

Data extraction and quality assessment

One reviewer (HA) extracted study characteristics (setting, participants, intervention, control, funding source) and outcome data from included trials. We contacted two authors for subgroup data on postmenopausal women. One author replied and provided relevant outcome data. Two reviewers (HA and SP) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool.10 Disagreements were resolved through discussion. We used RevMan V.5.3 to meta-analyse the data and generate forest plots.

Data synthesis and analysis

Outcomes measured in only one trial were reported narratively. Outcomes measured in more than one trial were synthesised quantitatively. We estimated between trial heterogeneity using the I2 statistic11 and used random effects meta-analyses to estimate pooled risk ratios and 95% CIs.12 We undertook sensitivity analyses to examine treatment effects according to study quality and assessed the impact of including data from a potentially eligible trial where the study author did not reply to our request for data on older participants.

Results

From 6645 records, we identified 53 studies for full-text review (see online supplementary appendix 2). Four studies were eligible for inclusion.13–16 Two studies recruited only postmenopausal women.15 16 Two studies recruited women of all ages but the median age was >50 years.13 14 For these studies, we contacted authors requesting data for postmenopausal women, or if menopausal status not ascertained, for women aged over 65. We received data from one author and hence included three trials consisting of 534 postmenopausal women in our review (table 1).14–16 We did not identify any studies that included older men.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Setting | Population | Intervention | Control | Confirmation of UTI | Outcomes |

| Raz 200315 | Outpatient infection disease clinics in Northern Israel | Community dwelling postmenopausal women with recurrent UTI* | Nitrofurantoin 100 mg capsule at night for 9 months, with placebo vaginal pessary to mimic control group | Vaginal pessary containing 0.5 mg estriol daily for 2 weeks, then once a fortnight for 9 months, with oral placebo capsules at night to mimic the intervention group | >103 colony-forming units/mL bacteria in midstream urine | 1. Number of women experiencing a recurrence during the prophylaxis period 2. Mean number of UTIs per woman during the prophylaxis period 3. Effects of oestrogens and antibiotics on vaginal mucosa, flora and pH 4. Mild and serious adverse events |

| Beerepoot 201216 | Community setting in Amsterdam | Community dwelling postmenopausal women with a self-reported history of at least three UTIs in the preceding year | Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole 480 mg tablet at night for 12 months, with placebo capsule twice daily | One capsule containing at least 109 colony-forming units of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 twice daily for 12 months, with placebo capsule at night | Symptoms ±>103 colony-forming units/mL bacteria in midstream urine | 1. Number of women experiencing a recurrence during, and 3 months after the prophylaxis period 2. Mean number of UTIs per woman during the prophylaxis period 3. Median time to first recurrence during and after the prophylaxis period 4. Effects of lactobacilli and antibiotics on vaginal flora 5. Effects of lactobacilli and antibiotics on urinary and faecal antibiotic resistance 6. Mild and serious adverse events |

| Kranjčec 201414 | Outpatients and primary care in Zabok, Croatia | Community dwelling women with self-reported recurrent UTI* | Nitrofurantoin 50 mg at night for 6 months | 2 g D-mannose powder diluted in 200 mL water at night for 6 months OR No treatment |

Symptoms and >103 colony-forming units/mL bacteria in midstream urine |

1. Number of women experiencing a recurrence during the prophylaxis period 2. Median time to first recurrence during the prophylaxis period 3. Adverse events |

*Recurrent UTI is defined as two confirmed episodes of uncomplicated UTI in 6 months or three in 12 months.

UTI, urinary tract infection.

Trial characteristics

Trials were conducted in community and outpatient settings in Israel, the Netherlands and Croatia. Only one trial included individuals with diabetes16 and only one trial included individuals with renal impairment.14 Intervention arms consisted of 6 to 12 months of antibiotic therapy. Control arms consisted of non-antibiotic prophylaxis with vaginal oestrogen pessaries,15 oral lactobacilli capsules16 and D-mannose powder.14 One trial reported the number of UTI recurrences per patient year during the prophylaxis period.16 All trials reported the number of women experiencing a UTI during the prophylaxis period and frequency of adverse events. Only one trial assessed recurrence of UTI after the prophylaxis perio.16 One trial assessed effect on urinary and faecal bacterial resistance.16

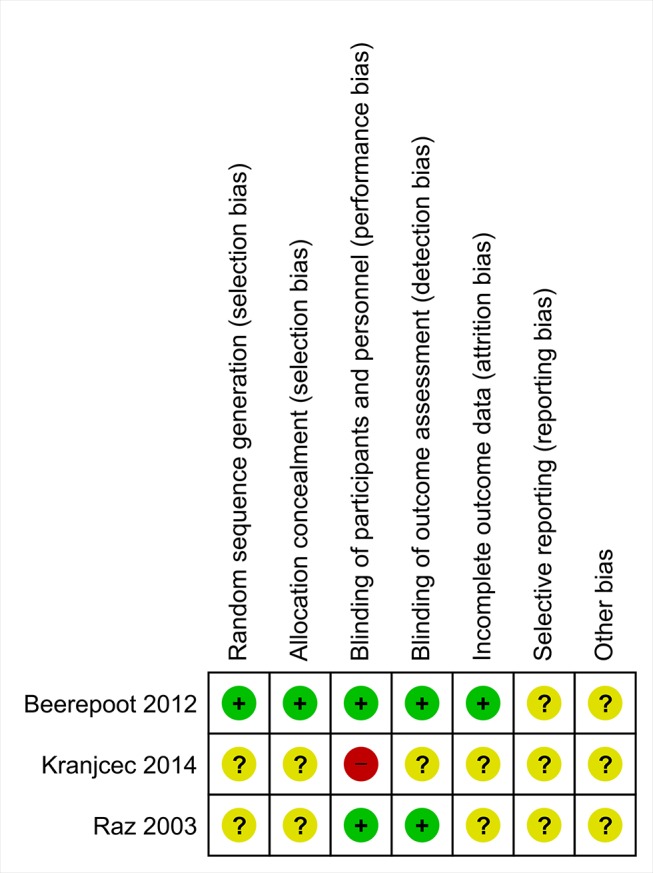

Risk of bias

Figure 1 summarises the risk of bias assessment. Allocation and randomisation details were poorly reported in two trials.14 15 One trial was assessed as high risk for performance and detection bias; trial arms consisted of an oral antibiotic capsule or D-mannose powder diluted in 200 mL water or no treatment with no use of placebo and did not report on blinding of outcome assessors.14 Only one trial reported a sample size calculation.14 Overall, one trial was judged to be low risk of bias16 and two trials unclear risk due to limited reporting of methods.14 15

Figure 1.

Summary of risk of bias assessment.

Effect of long-term antibiotics on recurrent UTI

Compared with a capsule of lactobacilli, prophylaxis with 480 mg of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole for 12 months led to fewer microbiologically confirmed UTI episodes per patient-year (mean number of episodes per year=1.2 vs 1.8, mean difference 0.6, 95% CI 0.0 to 1.4, p=0.02). Prophylaxis with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole also led to less women experiencing a microbiologically confirmed UTI during prophylaxis (49.4% vs 62.9%; RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.0) and an increase in time to first UTI (6 months versus 3 months; log-rank p=0.02). There was no difference between arms in the mean number of microbiologically confirmed UTI episodes 3 months after cessation of prophylaxis (mean number of episodes=0.1 vs 0.2, mean difference 0.0, 95% CI −0.1 to 0.3, p=0.64).16

Compared with vaginal oestrogen pessaries, prophylaxis with 100 mg of nitrofurantoin for 9 months led to fewer women experiencing a UTI during prophylaxis (42.3% vs 64.6%; RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.8 to 0.90) and a lower mean number of UTIs per woman (0.6 episodes per woman vs 1.6 episodes per woman).15

Compared with D-mannose powder prophylaxis with 50 mg of nitrofurantoin for 6 months led to more postmenopausal women experiencing a UTI during prophylaxis (24% vs 19%, RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.69).14

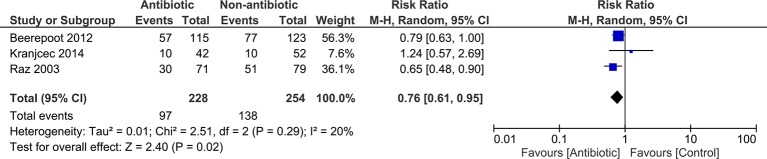

Random effects meta-analysis (figure 2) shows long-term antibiotic therapy reduces the risk of a woman experiencing a UTI during the prophylaxis period (pooled RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.95) with about eight post-menopausal women needing treatment with long-term antibiotics to prevent one woman experiencing a UTI during the prophylaxis period (number needed to treat (NNT)=8.5).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing results of meta-analysis for proportion of women experiencing a UTI during the prophylaxis period. UTI, urinary tract infection.

Adverse events

Commonly reported side effects across the three trials included skin rash, gastrointestinal disturbance and vaginal symptoms. There were no statistically significant difference between risk of adverse events between trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and lactobacilli,16 or between nitrofurantoin and vaginal oestrogens.15 Risk of side effects with D-mannose powder was significantly lower than with nitrofurantoin (RR 0.28; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.57).14 Overall, absolute numbers of serious adverse events or events resulting in treatment withdrawal were small.

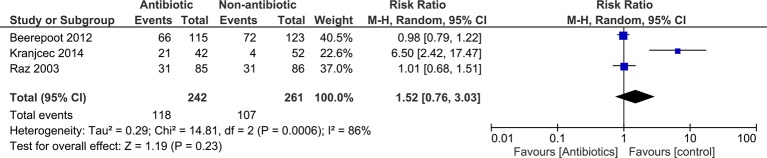

We had data on mild adverse events (not resulting in treatment withdrawal) for all three trials. There was marked heterogeneity between trials for adverse events (I2=86%).

Meta-analyses showed no statistically significant difference between antibiotics and control for overall risk of mild adverse events (pooled RR 1.52; 95% CI 0.76 to 3.03) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing results of meta-analysis for proportion of women experiencing mild side effect (treatment not withdrawn) during the prophylaxis period.

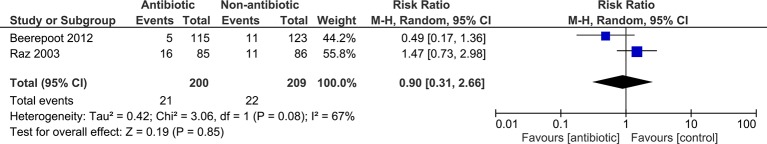

We extracted data for serious adverse events (resulting in treatment withdrawal) for two trials. Meta-analyses showed no statistically significant difference between antibiotics and control for overall risk of serious adverse events (pooled RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.31 to 2.66; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing results of meta-analysis for proportion of women experiencing a serious side effect (resulting in treatment withdrawal) during the prophylaxis period.

Effect of long-term antibiotic therapy on bacterial resistance

Compared with lactobacilli, women receiving 12 months prophylaxis with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole showed dramatic increases in the proportion of antibiotic resistant bacteria isolated from urine and faeces. For example, 20%–40% of urinary and faecal E coli isolates were resistant to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim and amoxicillin at baseline, increasing to 80%–95% after 1 month of treatment. Over the 15 month follow-up period, resistance levels decreased following cessation of prophylaxis but remained above baseline levels.16

Sensitivity analyses

We assessed the impact of removing the study at high risk of bias on effect size and direction.14 Removal made little difference to the meta-analysis for proportion of women experiencing a UTI during the prophylaxis period (pooled RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.89). Removal did impact on the meta-analysis for proportion of women experiencing mild side effects during the prophylaxis period but overall difference between antibiotics and placebo did not reach statistical significance (pooled RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.20).

We also pooled aggregate data from another potentially relevant study where authors did not respond to our request for data regarding postmenopausal women/women over 65.13 This study compared 500 mg of cranberry extract to 100 mg trimethoprim taken at night for 6 months. However, adding aggregate data for the whole study population (women aged 45 and above) to our meta-analysis for the proportion of women experiencing a UTI during the prophylaxis period made little difference to risk estimates (pooled RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.90).

Discussion

Summary

This systematic review assessed evidence from three European randomised trials reported between 2003 and 2014. Trials only included women. Compared with controls, long-term prophylaxis with antibiotics reduced the risk of postmenopausal women experiencing a recurrent UTI during the prophylaxis period, without a statistically significant increase in risk of adverse events. Data from one trial16 suggested this benefit was limited to duration of prophylaxis and was not apparent 3 months after cessation of prophylactic treatment. Data from one trial16 showed long-term antibiotic prophylaxis dramatically increased urinary and faecal antibiotic resistance. However, trials were small with relatively short follow-up and had limitations in design and reporting, with one trial judged high risk for bias.

Strengths and limitations

We conducted this review following prospective registration of a review protocol and in line with guidance from the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Our search strategies was comprehensive and supplemented with reviews of reference lists of relevant trials,13–16 systematic reviews8 17 18 and clinical guidelines.19–21 We contacted authors where additional data were required for study inclusion. Due to resource constraints, we limited searches to English language and may have missed potentially relevant studies.

Comparison with existing literature

Meta-analysis of 10 randomised trials of women aged 18 and older found long-term antibiotics reduced the risk of UTI recurrence during the prophylaxis period by almost 80% (RR 0.21; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.34; NNT=1.85).8 Our analyses showed a smaller effect size and greater NNT for postmenopausal women, possibly due to more complex pathophysiology of recurrent UTI in this population. We did not identify a statistically significant increase in risk of adverse events associated with use of antibiotics. Adverse events are often poorly reported in trials,22 and we found heterogeneity for adverse events between trials. In addition, the studies included in this review compared long-term antibiotic therapy with various non-antibiotic treatments and not placebo, and this may have influenced effect sizes for adverse events towards the null. We found small absolute numbers of serious adverse events and cannot exclude the possibility of important effects being missed in these relatively small studies.

During two point prevalence surveys, almost half of all adults residing in a sample of care homes were prescribed antibiotics for prevention of recurrent UTI.1 2 Based on three small trials, with relatively short follow-up periods and design limitations, our meta-analyses suggest that this widely practised use of prophylaxis reduces risk of recurrence in women. However, it is still unclear if these benefits extend to older men or frailer care home populations. These are important gaps in current evidence, especially given large-scale observational data showing 10% of older men who experience an acute UTI go on to have at least one recurrence.23

Only one study followed up participants after cessation of prophylaxis and found that beneficial effects had ceased after 3 months.16 Previous studies of younger women have reported similar findings suggesting that prophylaxis only confers protection from recurrence during the active prophylaxis phase.8

We found little data on the impact of long-term antibiotic therapy on antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic use is associated with increased risk of resistance.3 Given the potential harms from acquiring an antibiotic resistant infection, the risk inferred by long-term antibiotic use is an important factor to consider with patients when making decisions about antibiotic prophylaxis.

Implications for research and practice

Based on the data we analysed, a pragmatic approach is required when considering prescribing long-term antibiotics in older patients with recurrent UTI. Although long-term antibiotics may reduce the risk of UTI recurrence in women, this benefit diminishes on cessation of treatment. Little is known about optimal prophylaxis period, long-term effects on health, risk of antibiotic resistant infections, effect in older men, effect in frail care home residents or impact on important patient-centred outcomes. These unknowns must be balanced against benefits and patient preferences.

Future research efforts on recurrent UTI should focus on improving the design and reporting of trials and developing a core set of outcomes to allow better synthesis of trial data. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be compared with non-antibiotic prophylaxis with some evidence of efficacy (such as vaginal oestrogens) rather than those with little or poor evidence of efficacy. Researchers should address unanswered questions regarding long-term effects, duration of use, adverse effects and antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

There is ongoing uncertainty around the benefits and harms of long-term antibiotics in older men and frail care home residents with recurrent UTI. Prescribing long-term antibiotics to older women with recurrent UTI needs careful discussion between patient and clinician of reduced risk of relapse, potential increases in urinary and faecal antibiotic resistance and rapidly diminished benefit once prophylaxis stops.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bojana Kranjčec, Dino Papeš and Silvio Altarac for providing requested data.

Footnotes

Contributors: HA, CB, NF, DF and SP conceived and designed the study. HA and FD did the searches. HA, FD and SP assessed studies for inclusion and risk of bias and extracted relevant data. HA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to further drafts and final manuscript.

Funding: This report is an independent research arising from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship awarded to Haroon Ahmed, and supported by Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS Wales, HCRW or the Welsh Government. The funders had no role in the design or preparation of this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.McClean P, Tunney M, Gilpin D, et al. . Antimicrobial prescribing in residential homes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:1781–90. 10.1093/jac/dks085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClean P, Tunney M, Gilpin D, et al. . Antimicrobial prescribing in nursing homes in Northern Ireland: results of two point-prevalence surveys. Drugs Aging 2011;28:819–29. 10.2165/11595050-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. . Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:c2096 10.1136/bmj.c2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodford HJ, George J. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:107–14. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMurdo ME, Gillespie ND. Urinary tract infection in old age: over-diagnosed and over-treated. Age Ageing 2000;29:297–8. 10.1093/ageing/29.4.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoniou T, Gomes T, Juurlink DN, et al. . Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced hyperkalemia in patients receiving inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1045–9. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fralick M, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, et al. . Co-trimoxazole and sudden death in patients receiving inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system: population based study. BMJ 2014;349:g6196 10.1136/bmj.g6196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert X, Huertas I, Pereiró II, et al. . Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;3:Cd001209 10.1002/14651858.CD001209.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al. . A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMurdo ME, Argo I, Phillips G, et al. . Cranberry or trimethoprim for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections? A randomized controlled trial in older women. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:389–95. 10.1093/jac/dkn489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kranjčec B, Papeš D, Altarac S. D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a randomized clinical trial. World J Urol 2014;32:79–84. 10.1007/s00345-013-1091-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raz R, Colodner R, Rohana Y, et al. . Effectiveness of estriol-containing vaginal pessaries and nitrofurantoin macrocrystal therapy in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:1362–8. 10.1086/374341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beerepoot MA, ter Riet G, Nys S, et al. . Lactobacilli vs antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections: a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:704–12. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beerepoot MA, Geerlings SE, van Haarst EP, et al. . Nonantibiotic prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Urol 2013;190:1981–9. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, et al. . Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(2):Cd005131 10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SIGN. Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2015. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign88.pdf.

- 20.Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. . International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the infectious diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:e103–20. 10.1093/cid/ciq257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dason S, Dason JT, Kapoor A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5:316–22. 10.5489/cuaj.687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodkinson A, Kirkham JJ, Tudur-Smith C, et al. . Reporting of harms data in RCTs: a systematic review of empirical assessments against the CONSORT harms extension. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003436 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drekonja DM, Rector TS, Cutting A, et al. . Urinary tract infection in male veterans: treatment patterns and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:62–8. 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015233supp002.doc (66.5KB, doc)

bmjopen-2016-015233supp001.pdf (48.1KB, pdf)