Abstract

Objective

To identify components of a proposed blood-borne virus (BBV) population screening programme and its associated consent procedure that both the public and health practitioners (HPs) would find acceptable. The proposed BBV screening system would aim to reduce late diagnosis of BBVs and be used in patients undergoing routine blood tests, aided by risk stratification software to target individuals at higher risk of infection.

Design

A Delphi technique was used to build consensus among two separate groups, public participants and HPs in England.

Methods

A survey incorporating vignettes was developed, with input from an external panel of experts. Over three rounds, 46 public participants and 37 HPs completed the survey, rating statements on a four-point Likert scale. The survey covered issues around stigma and sensitivity, the use of risk stratification algorithms and ‘limited’ patient consent (ie, preinformed of the option to ‘opt-out’). Consensus was defined as >70% of participants agreeing or disagreeing with each statement.

Results

Consensus was achieved among both groups in terms of acceptability of the screening programme. There was also consensus on using patient data to risk-stratify screening algorithms and the need to obtain some form of consent around the time of drawing blood.

Conclusions

This study found that the special protected status of HIV in England is no longer deemed necessary today and hinders appropriate care. We propose that a novel ‘limited consent procedure’ could be implemented in future screening programmes.

Keywords: HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, screening, testing, consensus building, consent

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A broad range of healthcare workers and members of the public were sampled in this nationally representative study.

Use of a Delphi consensus building technique allowed an iterative approach to achieve consensus in an area of public health with considerable potential for ethical debate.

The study’s methodology may be of interest to other countries considering such a screening programme.

The application of this study’s results is limited to the UK, which has a different medicolegal framework in relation to consent, testing and screening compared with other countries.

While we attempted to send invitations to a broad range of specialists and professionals for the HP survey, the study topic might still have attracted more of those with strong views.

Introduction

Globally, around 47% of people living with HIV (PLWH) in 2014 were not aware that they were infected.1 The Joint United Nation Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAID) ‘90–90–90’ target,1 with the ambition that 90% of PLWH will know their HIV status by 2020, is unlikely to be achieved, especially in some countries with relatively low economic development. The situation for the other two main blood-borne viruses (BBVs), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), is worse in terms of levels of undiagnosed infections.2–7 Failure of timely diagnoses of HIV or other BBVs leads to continued transmission of infections as well as worse clinical outcomes. Late diagnosis of HIV is associated with a 10-fold higher risk of death in the year after diagnosis than early diagnosis.8 Late diagnosis of HBV or HCV is also associated with higher mortality due to liver cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer. Most HCV infections can now be cured, and both HBV and HIV infections controlled with antiviral therapy, if detected sufficiently early with a good prognosis for most patients.

In many highly economically developed countries, reliable tests to diagnose BBVs have been widely available since the 1980s and early 1990s. In the case of HIV, testing has been viewed differently to tests for other infections or serious medical conditions; often it requires specific consent from individuals for the test, a process termed ‘HIV exceptionalism’.9 This stemmed historically from when HIV was an untreatable disease10 and carried much social stigma, as HIV was widely associated with men who have sex with men (MSM) or intravenous drug users.11 Despite improvements in health outcomes, knowledge that HIV can infect any demographic group and attitudes towards MSM, such stigma still remains, both among health practitioners (HPs) and the public. As a result, attempts to screen for HIV infections more widely, which rely on HPs to identify patients potentially at risk, have been hindered. Moreover, the necessity of obtaining specific consent for HIV testing has remained an additional barrier to wider or universal screening. Despite this barrier, HIV testing has become more normalised over the last decade with the introduction of ‘opt-out’ HIV testing,9 12 self-testing kits and the recommendations for universal testing in some clinical settings, particularly in pregnant women and patients attending sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics.10 Testing coverage in other clinical settings has been less good.

Studies in the UK have shown that there has been missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis; high proportions of patients with advanced HIV infection attended primary care or other healthcare facilities with indicator conditions in the 1–2 years prior to diagnosis, but were not tested.13–16 Recognised barriers to more widespread HIV testing by healthcare workers include failure to identify risk factors, lack of training or knowledge and concerns that a patient may be offended if a test is recommended.11 17 Efforts to increase HIV testing in clinical settings, such as emergency departments, have been partially effective, however, required significant additional resources and are difficult to maintain.13–15 Even when programmes have been implemented to establish routine HIV or BBV testing in emergency rooms, most programmes have not managed to increase the proportion of patients tested to above 50%.13–16

New approaches to increase HIV and BBV testing and to reduce rates of undiagnosed infections and late diagnosis are needed. Moreover, approaches to testing which do not require specific consent for HIV tests are likely to simplify screening and increase testing rates. In many highly economically developed countries, for example, the UK, around half of the population have a blood test of some form every year, providing a potential opportunity for BBV testing via a population screening strategy.18 Such a process might be used for universal screening, or to target only patients identified as being at higher risk of BBV infection, through risk stratification, in order to make testing cost-effective. Risk stratification would most effectively be performed by algorithms in computer physician order entry (CPOE) systems which might also interact with electronic patients records (EPR) or other computer health systems. Such software algorithms might identify those at higher risk on the basis of patient demographic characteristics, specific data or diagnostic codes in EPRs, previous abnormal test results (eg, lymphopenia or raised aminotransferase levels (ALT) or from specific tests being ordered on CPOEs (eg, syphilis serology). However, gaining specific consent for BBV screening from individuals at the point of drawing blood in such a system would be challenging. Even when using the ‘opt-out’ approach, many physicians would find the requirement to obtain specific consent from all patients who might be selected for screening onerous, given the time needed to counsel some patients. One alternative would be to gain limited consent, whereby patients are notified in advance via written communication that their blood samples may be tested for BBVs, and also given the opportunity to ‘opt-out’ of the screening programme. In this case, patients would not be asked to consent specifically for HIV/BBV testing by the healthcare practitioner directly. Such a method of gaining limited consent might be viewed as both practical and reasonable, particularly given that the benefit of identifying people with undiagnosed BBV infections applies to their individual health and to society via reducing BBV transmission. However, it has yet to be determined whether this approach of limited consent would be considered acceptable. The aim of this study was to identify components of a BBV population screening programme and associated consent procedure that both the public and HPs would find acceptable.

Methods

Study design

The study was designed using a Delphi method, a consensus-building technique that has been used widely in various areas of medical practice to achieve consensus among HPs and patients, on acceptable and effective medical practice and health service provisions.19 20 An online survey was created using Bristol Online Survey (www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk) entailing four sections with vignettes and subsequent statements encompassing our research questions. Free text comment boxes at the end of each section allowed participants to provide additional comments and feedback.

Patient involvement

The only patient involvement in this study is on the advisory panel who aided in the process of survey development.

Participants and recruitment

Members of the public were randomly selected through a commercial survey database covering potential participants across the whole of the UK and invited by email to fill in the questionnaire. After invitations were sent out, all responses were accepted sequentially until either the target number of respondents had completed the survey or the 4-week time limit for the survey had been reached. After this, no further participants were allowed to begin the survey. HPs were purposefully selected through relevant English National Health Service (NHS) organisations. HPs were deliberately selected from a wide range of relevant medical specialists, general practitioners and specialist nurses. Potential participants (1000 public and 400 HPs) were emailed with a description of the study and a link to the online survey and asked if they would be willing to take part. Public participants were offered a financial incentive of a £5 Amazon gift voucher after each round to improve recruitment. In Delphi exercises, 50 respondents are generally considered to be sufficient to be representative of public opinion and 30 respondents sufficient to be representative of expert opinion to enable consensus to be achieved.20–25 A dropout rate of 20% was expected over the three rounds, as this is found to be normal in other studies.25 26 Therefore, we sought to recruit 75 members of the public and 50 HPs to be able to achieve the target sample size at the end of three rounds.

Survey development

The survey was developed by the research team with input from an external advisory panel comprising national experts in bioethics, medicine and Delphi methodology. Based on our review of the literature, we developed three general topic areas relevant to the proposed screening programme: stigma and sensitivity, the use of computer selection (risk stratification) algorithms/programs for BBV screening and patient consent. To illustrate issues in each area, we wrote a number of clinical vignettes, an approach to Delphi used previously to explore ethical dilemmas.23 The vignettes comprised short hypothetical scenarios encompassing the general topic areas that may be experienced by the public and HPs (see online supplementary file) followed by a series of statements. Two statements were constructed for each question in order to balance negative and positive responses. Participants were asked to rate each statement using a 4-point Likert scale with a response of ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree.’ Statements were assessed by the advisory panel for readability and relevance.

bmjopen-2016-015373supp001.pdf (206.1KB, pdf)

Data collection

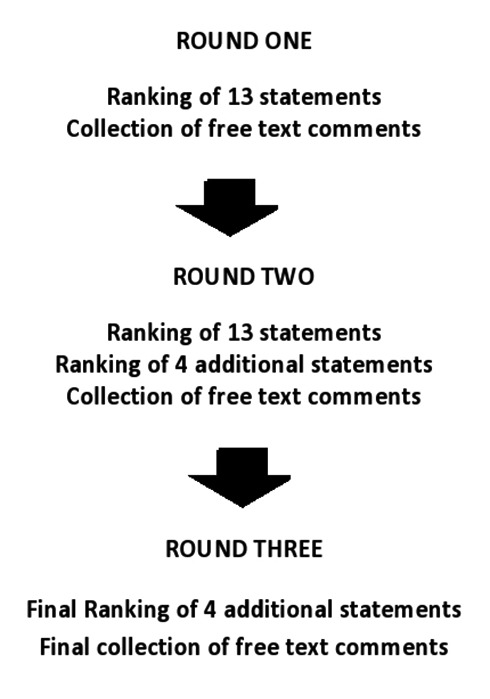

Data were collected over three rounds; the process is summarised in figure 1. Round 1 responses were analysed, and areas requiring further investigation in round 2 were identified. Feedback from rounds 1 and 2 was provided to the participants, with pie charts indicating group consensus and disagreement as well as the respondents’ original answers. Respondents were then asked to reconsider the original answer in light of the group’s responses.

Figure 1.

The three Delphi rounds.

Free text comment boxes were provided at the end of each section for participants to provide any further comments, and we gathered data on participants’ age, gender and ethnicity. To help participants understand the proposed BBV screening programme, we embedded a link in the online survey to an informational YouTube video developed by DC.27

Data analysis

Following completion of the third and final round, responses were analysed to establish areas of consensus and areas where consensus had not been achieved. In the final analysis, percentages were narrowed down to agree (strongly agree and agree) and disagree (strongly disagree and disagree); percentages of agree/disagree were calculated for each statement using SPSS V.10. Consensus was defined as >70% of participants agreeing/strongly agreeing or disagreeing/strongly disagreeing with each statement; this percentage is recommended to achieve general consensus.25 28 29 A modified continuous comparative method of thematic analysis was used to analyse the free text comments in order to identify themes, allowing the determination of whether a comment made by one participant was a commonly shared or individual opinion.30

Results

In round 1, a total of 119 participants (68 public and 51 HP participants) were recruited; in round 2, 51 public and 40 HPs completed the survey; in round 3, 46 public and 37 HPs completed the survey. Within the final sample of HP respondents 55% were hospital doctors, 23% general practitioners and 12% specialist nurses; table 1 shows the demographic data collected for the public and HP participants. Table 2 summarises consensus achieved in all three rounds, and table 3 summarises common themes collected from all the participants free text comments.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic data

| Sociodemographic questions | Public (n=46) |

HP (n=37) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Age range (years) | 20–73 | 29–61 |

| Mean age (years) | 33 | 44 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 21 (46%) | 22 (59%) |

| Female | 25 (54%) | 15 (41%) |

| Ethnicity (self-defined) | ||

| White British | 33 (72%) | 31 (84%) |

| Asian | 7 (15%) | 3 (8.5%) |

| Indian | 3 (7%) | 1 (2.5%) |

| Chinese | 1 (2%) | 1 (2.5%) |

| American | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| African | 0 | 1 (2.5%) |

HP, health practitioner.

Table 2.

Frequency of responses to the survey

| Statement | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |||||||||

| Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | |||||||

| Public | HPs | Public | HPs | Public | HPs | Public | HPs | Public | HPs | Public | HPs | |

| Stigma and sensitivity | ||||||||||||

| 1. HIV tests should no longer have a special status and should be handled like any other routine blood tests | 85% | 75% | 15% | 25% | 80% | 84% | 20% | 16% | 80% | 88% | 20% | 12% |

| 2. Because having HIV may make people feel they have a stigma; HIV tests should only be carried out in cases where the doctor will not offend the patient | 57% | 6% | 43% | 94% | 60% | 0% | 40% | 100% | 60% | 2% | 40% | 98% |

| 3. It is acceptable for a HP not to recommend that a patient has a HIV test if the HP feels too uncomfortable | 40% | 2% | 60% | 98% | 41% | 0% | 59% | 100% | 41% | 0% | 59% | 100% |

| The use of computer selection programmes for screening | ||||||||||||

| 4. The BBV screening programme is acceptable because detecting infections more often will benefit individual patients and the wider community | 75% | 67% | 25% | 33% | 78% | 69% | 22% | 31% | 78% | 75% | 22% | 25% |

| 5. The BBV screening programme is not acceptable because it tests people for BBVs without their consent | 51% | 53% | 49% | 47% | 57% | 63% | 43% | 37% | 57% | 70% | 43% | 30% |

| 6. The computer programme should not be able to use information on the patient (eg, age, post code or results of a previous test) to select blood samples for BBV testing | 60% | 45% | 40% | 55% | 49% | 26% | 51% | 74% | 49% | 22% | 51% | 78% |

| 7. A screening programme for BBV infections would help remove the burden of having to identify and counsel patients for HIV and BBV testing | 76% | 49% | 34% | 51% | 75% | 37% | 25% | 63% | 75% | 32% | 25% | 68% |

| 14. Assuming patients’ data were fully secure, a screening programme for BBV infections should be able to use patient information to select those most at risk of infections for screening | – | – | – | – | 74% | 84% | 26% | 16% | 72% | 98% | 28% | 2% |

| 15. A screening programme for BBV infections should not be allowed to use patient information to select those at most risk of infections even assuming the data were fully secure | – | – | – | – | 63% | 16% | 37% | 84% | 63% | 6% | 37% | 94% |

| Patient consent | ||||||||||||

| 8. Posters and leaflets informing patients that they may be screened for BBV infections is an acceptable way to get consent | 70% | 53% | 30% | 47% | 57% | 42% | 43% | 58% | 57% | 35% | 43% | 65% |

| 9. Using posters and leaflets is not enough. The HP should still speak to patients and tell them that their blood may be tested for BBV infections and get their fully informed consent | 83% | 74% | 17% | 26% | 80% | 84% | 20% | 16% | 80% | 85% | 20% | 15% |

| 10. Any loss in patient choice is outweighed by the benefit of having infections diagnosed earlier | 75% | 51% | 25% | 49% | 71% | 26% | 29% | 74% | 71% | 32% | 29% | 68% |

| 11. There is not adequate information for a patient to decline BBV testing for this screening programme | 68% | 39% | 32% | 61% | 67% | 47% | 33% | 53% | 67% | 42% | 33% | 58% |

| 12. Offering a mix of types of consent to patients getting routine blood tests is more acceptable than offering limited consent only | 85% | 90% | 15% | 10% | 75% | 84% | 25% | 16% | 75% | 90% | 25% | 10% |

| 13. Even though it may cost more money overall, offering a mix of types of consent to patients getting routine blood tests is the most acceptable way of getting consent | 78% | 86% | 22% | 14% | 75% | 84% | 25% | 16% | 75% | 90% | 25% | 10% |

| 16. This system of informing patients of the screening programme and permitting opt-out is sufficient for ensuring limited consent and patient awareness | – | – | – | – | 69% | 68% | 31% | 32% | 59% | 62% | 41% | 38% |

| 17. This system is not sufficient for ensuring patients are aware their blood may be tested. All patients undergoing blood tests should also be asked to agree to taking part in the screening programme by a doctor or nurse practitioner | – | – | – | – | 73% | 53% | 27% | 47% | 63% | 73% | 37% | 27% |

Percentage figures in bold indicate where consensus was achieved.

BBV, blood-borne virus; HP, health practitioner.

Table 3.

Common themes from participants’ free text comments.

| Stigma and sensitivity | |

| Public | ‘It should be carried out like any normal blood test…then the doctor couldn’t be offending anyone or be embarrassed’ ‘The stigma surrounding HIV would be reduced if HIV blood tests become more routine’ |

| HP | ‘I feel there is a need for the position of testing to be brought in line with all other tests’ ‘HIV testing would become more routine if it were offered more often’ |

| The use of computer selection programs for screening | |

| Public | ‘I don’t feel comfortable with patients being selected based on age and post code…it’s acceptable for tests to be run based on prior results’ ‘I believe that implementing it would be a tremendous service if applied ethically and sensitively’ ‘If data is secured and patients aware then it should be allowed’ |

| HP | ‘We need universal not targeted screening’ ‘If we are saying that anyone can get these infections, then surely we should check everyone’ ‘Testing on the basis of age etc. will miss a large proportion of the population’ |

| Patient consent | |

| Public | ‘While the BBV programme is in the public interest, it is vital that efforts are made to inform patients of what is happening’ ‘As long as the patients are fully informed there is no problem’ ‘A mixture of consent and acting in the best interests of the patient would be one of the best methods to ensure wide acceptability of the programme’ |

| HP | ‘People are careened for many illnesses without fully informed consent, BBV should be no different’ ‘Akin to random testing for diabetes, you may inform the patient that the test is happening but would not necessarily discuss all the subsequent effects and treatments’ ‘I am sure that as patients become more aware of this happening to their bloods, they will be more accepting of it and ultimately see it as ‘routine’’ |

Stigma and sensitivity

There was clear consensus for this section. The public and HPs agreed that HIV should no longer have a special status and should be handled like any other routine blood tests. In response to Question 3, HPs unanimously disagreed that feelings of discomfort or offending patients was an acceptable reason not to offer HIV tests.

The use of computer selection programs for screening

The public and HPs both agreed that a BBV screening programme would detect infections more often and would be beneficial to individual patients and society more widely. However, HPs contradicted themselves by also agreeing that the BBV screening programme was not acceptable as it ‘tested patients without their consent’. Despite this, HPs felt that computer programmes should be able to use patients’ information for risk stratification. Similarly, the public agreed that the screening programme would help to remove the burden of identifying and counselling patients. Free text comments from round 1 generally supported the concept of using patient data for risk stratification, so long as there were safeguards to ensure data were secure. In round 2, a follow-up question (statements 14 and 15) confirmed that use of patient data for these purposes would be acceptable assuming data were secure.

Patient consent

Consensus was achieved in both groups on the point that it was not enough to inform patients that they may be tested for BBVs via a poster or leaflets alone. Both the public and the HPs agreed that getting fully informed consent for BBV testing was ideal. However, the public also agreed that any loss in patient choice (ie, autonomy) would be outweighed by having infections diagnosed earlier. For the option to offer a mix of consent options, rather than limited consent alone, the answers were irreconcilable, with the majority of both groups agreeing with the two opposing statements. However, this likely instead reflects views that reducing healthcare costs should not be prioritised over obtaining sufficient consent. Free text comments in this section mostly supported the proposed consent process, but emphasised the need for all patients to be informed that their blood samples might be tested. Two new statements (16 and 17) were added in round 2 to try and establish consensus regarding the proposed method of consent. There was consensus among HPs that patients should still be informed that their blood might be tested for BBVs at the point of drawing blood.

Discussion

This study was developed to examine attitudes of the public and HPs towards two mechanisms of improving detection of HIV and BBV infections, the use of risk stratification algorithms to detect patients at higher risk of infection and limited consent. We used an iterative Delphi technique with the addition of new statements in subsequent rounds to clarify issues raised after responses to prior statements. We found there was general agreement among both participant groups around ending any persisting exceptionalism in relation to HIV testing. There was also consensus that a BBV screening programme would be beneficial and it was reasonable to use patients’ medical data to target those at higher risk of infection, assuming data were protected.

In respect to our investigation of a modified consent process, there was some ambiguity within both groups. Therefore, consensus on this point was not easily discernible, indicating this form of consent posed some ethical dilemma. However, through iteration of rounds and use of free text boxes, a new and acceptable form of a consent process emerged from this Delphi study. We call this process ‘limited consent’ which involves providing advanced notification to all patients that their blood may be tested, with a reminder from a HP when blood is drawn, along with the option of opting out. This Delphi study achieved a national English sample from a range of HPs involved in BBV testing and the general public. Its finding of acceptability of a novel consent procedure and implications for the development of a new BBV screening programme, however, may be applicable only to the English social context.

Given the apparent sensitivity that still exists around offering HIV testing, it is interesting that both public participants and a varied range of medical and nursing HPs were comfortable with the concept of reducing the exceptionalism that has traditionally been associated with HIV testing and with the concept of prior consent. In devising the statements in the survey, we deliberately wanted to test how far each group might consider balancing the primacy of patients’ autonomy, in terms of deciding whether to be tested for BBVs, over the competing ethical principal of utilitarianism. The utilitarian argument in favour of universal or targeted screening for BBVs is that society as a whole benefits if more people are diagnosed with BBV infections since transmission is reduced, fewer individuals are infected and healthcare costs are reduced.

Unlike some other screening programmes, the benefits of the proposed BBV screening programme would extend more widely than to just those individuals found to be infected with BBVs. Another significant difference is that given the frequency with which patients in general have blood tests and potential uncertainty of which patients would be tested using risk stratification algorithms, obtaining specific and direct consent for testing each time a patient has blood drawn is impractical. Hence, obtaining prior consent from the target adult population with the clear option of opting out of testing may prove both practical and acceptable based on our study.

There is a precedent for this form of consent in the UK Clinical Practice Research Database,31 where all adults in the areas contributing medical data to this system are informed by letter that their fully anonymised data may be used for research studies or service planning unless they decide to ‘opt-out’ of the system. One recent study screening for BBVs in emergency departments has also successfully employed a pragmatic and limited consent process.16 The use of risk stratification software to identify patients at higher risk of BBV infections has recently been employed in the UK-based HepCATT trial, as part of targeted case finding for hepatitis C infection in primary care.32 We believe that combining such risk stratification software to target screening with a practical and acceptable consent process has considerable potential to reduce the number of individuals with undiagnosed BBVs in countries with suitable health infrastructure. Further research into its design and implementation would be needed.

A recent UK study found that adding HBV/HCV tests to routine HIV tests in emergency departments resulted in significant numbers of new diagnoses of viral hepatitis as well as HIV, with the cost per new diagnosis well below the threshold for cost-effectiveness.13 This adds weight to the concept of screening specific or general populations for all three BBVs, rather than just HIV. Changing to the new consent process led to testing rates increasing from below 5% of all patients to consistently over 60% with mean numbers of positive results increasing from less than one per week to four per week.16

The process of obtaining consent in the present study may be viewed as a paradigm for future screening programmes or studies exploring alternative approaches to increase BBV testing. Our study adds to the evidence suggesting that both the public and HPs may be willing to accept prior consent, where HPs do not need to obtain specific consent for HIV or BBV testing, given the benefits of earlier diagnosis of BBV infections both to individuals and society in general. Nonetheless, there are potential challenges in implementing such a system of prior consent for BBV testing in terms of public policy or law. In the UK, consent for medical tests and treatment or use of medical data for specific purposes is required by common law,33 although in practice the precise nature of most blood tests ordered by clinicians are not discussed in detail with patients. As such, it may be feasible to test such a screening programme without serious legal barriers. In other countries where laws on consent and privacy relating to medical tests and use of data are different, adoption of such a programme may prove more problematic.

Conclusion

This study has a number of strengths and limitations. The study used a Delphi consensus technique allowing an iterative approach to achieve consensus in an area of public health with considerable potential for ethical debate. We successfully recruited a broad range of healthcare workers and members of the public with a sample size appropriate to the methodology, thus producing a nationally representative sample. However, the application of the study’s findings are restricted to the UK, given that other countries have different medicolegal systems in relation to consent and use of data, although our methodology may be of interest to other countries considering a screening programme. Another limitation is that the selection process for HP participants might have led to self-selection bias. While we attempted to send invitations to a broad range of specialists and professionals for the HP survey, the topic might still have attracted more of those with strong views. However, this is a selection bias that applies to any kind of questionnaire study and is not specific only to our study.

HIV-related issues, such as treatment and social stigma, have developed over the past couple of decades, and associated BBV screening programmes should reflect these advances. This study found that the special status of HIV testing in the UK may no longer be necessary today and is hindering appropriate screening and proposes a novel consent procedure that could be implemented in future screening programmes in the UK. Our findings could be used to inform the development of public policy that would facilitate such a BBV screening programme, as well as the development of professional education in terms of reducing the social stigma associated with HIV and strengthening communication between clinicians and their patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the doctors, nurses and public participants who responded to our survey, Charlotte Jacobs our study coordinator and Robbie Horton who developed the YouTube video. We are indebted to the following expert advisors who assisted with the survey development and interpretation of responses: Dr Alasdair MacSween, Teesside University; Dr Elaine Kirk, GP at NHS England; Professor Rebecca Bennett, Manchester University, Professor Jackie Leach Scully, Newcastle University; Neil Campling and Alex Murray.

Footnotes

Contributors: DC, EJH and DRC were all responsible for the conception and design of this study, interpretation of the data, drafting, revising and approval of the final document.

DC was responsible for recruitment of the participants, collection and analysis of the data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Durham University School of Medicine, Pharmacy and Health’s Sub-Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Joint United Nation Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90-90-90 UNAIDS – an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS. 2014. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf accessed 09 Sep 2016.

- 2.Moorman AC, Xing J, Ko S, et al. . Late diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection in the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS): missed opportunities for intervention. Hepatology 2015;61:1479–84. 10.1002/hep.27365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederau C. Chronic hepatitis B in 2014: great therapeutic progress, large diagnostic deficit. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:11595–617. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornberg M, Razavi HA, Alberti A, et al. . A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Europe, Canada and Israel. Liver Int 2011;31(Suppl 2):30–60. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency. Hepatitis C in the United Kingdom: 2013 report. London: Health Protection Services, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health England. Hepatitis C in the UK: 2013 report. Public Health England: London: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/364074/Hepatitis_C_in_the_UK_2013.pdf(accessed 09 Sep 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Leary MC, Sarwar M, Hutchinson SJ, et al. . The prevalence of hepatitis C virus among people of south asian origin in Glasgow - results from a community based survey and laboratory surveillance. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013;11:301–9. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson S, Valappil M, Moses SE, et al. . Targeted case finding for hepatitis B using dry blood spot testing in the British-Chinese and south asian populations of the North-East of England. J Viral Hepat 2013;20:638–44. 10.1111/jvh.12084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein N. Ethics in consent for HIV testing. Virtual Mentor 2009;11:959–61. 10.1001/virtualmentor.2009.11.12.jdsc1-0912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayer R, Fairchild AL. Changing the paradigm for HIV testing – the end of exceptionalism. N Engl J Med 2006;355:647–9. 10.1056/NEJMp068153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.General Medical Council (GMC). Confidentiality: protecting and providing information (2000). 2016. GMC-UK-org http://www.gmc-uk.org/confidentiality_sep_2000.pdf_25416426.pdf (accessed 09 Sep 2016).

- 12.General Medical Council (GMC). Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. GMC-UK. org; 2008. http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/Consent_-_English_1015.pdf (accessed 09 Sep 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orkin C, Flanagan S, Wallis E, et al. . Incorporating HIV/hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus combined testing into routine blood tests in nine UK Emergency Departments: the "Going Viral" campaign. HIV Med 2016;17:222–30. 10.1111/hiv.12364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmahdi R, Gerver SM, Gomez Guillen G, et al. . Low levels of HIV test coverage in clinical settings in the U.K: a systematic review of adherence to 2008 guidelines. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:119–24. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartney T, Kennedy I, Crook P, et al. . Expanded HIV testing in high-prevalence areas in England: results of a 2012 audit of sexual health commissioners. HIV Med 2014;15:251–4. 10.1111/hiv.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paparello J, Hunter L, Betournay R, et al. . Reducing the barriers to HIV testing – a simplified consent pathway increases the uptake of HIV testing in a high prevalence population. HIV Medicine 2016;17(Suppl 1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.British HIV Association (BHIVA), British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH), British Infection Society (BIS). UK National Guideline for HIV testing 2008. BHIVA.org 2008. http://www.bhiva.org/documents/Guidelines/Testing/GlinesHIVTest08.pdf (accessed 09 Sep 2016)

- 18.http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Blood-tests/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed 09 Sep 2016)

- 19.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.http://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/64839/FullReport-hta2030.pdf (accessed 09 Sep 2016)

- 21.Cook S, Aikens JE, Berry CA, et al. . Development of the diabetes problem-solving measure for adolescents. Diabetes Educ 2001;27:865–74. 10.1177/014572170102700612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose CM, Kagan AR. The final report of the expert panel for the radiation oncology bone metastasis work group of the American College of Radiology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;40:1117–24. 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00952-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wainwright P, Gallagher A, Tompsett H, et al. . The use of vignettes within a Delphi exercise: a useful approach in empirical ethics? J Med Ethics 2010;36:656–60. 10.1136/jme.2010.036616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wigton RS, Darr CA, Corbett KK, et al. . How do community practitioners decide whether to prescribe antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections? J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1615–20. 10.1007/s11606-008-0707-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson EJ, Rubin GP. Development of a community-based model for respiratory care services. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:193 10.1186/1472-6963-12-193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:37 10.1186/1471-2288-5-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlSsgKsoAKM (accessed 09 Sep 2016)

- 28.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. . Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. . Standardised method for reporting exercise programmes: protocol for a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006682 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) opt-out system for members of the public. https://www.cprd.com/membersofpublic/ (accessed 09 Sep 2016).

- 32.Roberts K, Macleod J, Metcalfe C, et al. . Hepatitis C – assessment to treatment trial (HepCATT) in primary care: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:366 10.1186/s13063-016-1501-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.http://www.qmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_common_law.asp (accessed 17 Mar 2017)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015373supp001.pdf (206.1KB, pdf)