Abstract

Objective

The aim of this research is to implement and reliably evaluate primary human papillomavirus (HPV) screening in an established and routinely running organised, large-scale population-based screening programme.

Participants

Resident women in the Stockholm/Gotland region of Sweden, aged 56–60 years were randomised to either (1) screening with cervical cytology, with HPV test in triage of low-grade cytological abnormalities (old policy) or (2) screening with HPV testing, with cytology in triage of HPV positives (new policy).

Outcome

The primary evaluation was the detection rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+).

Results

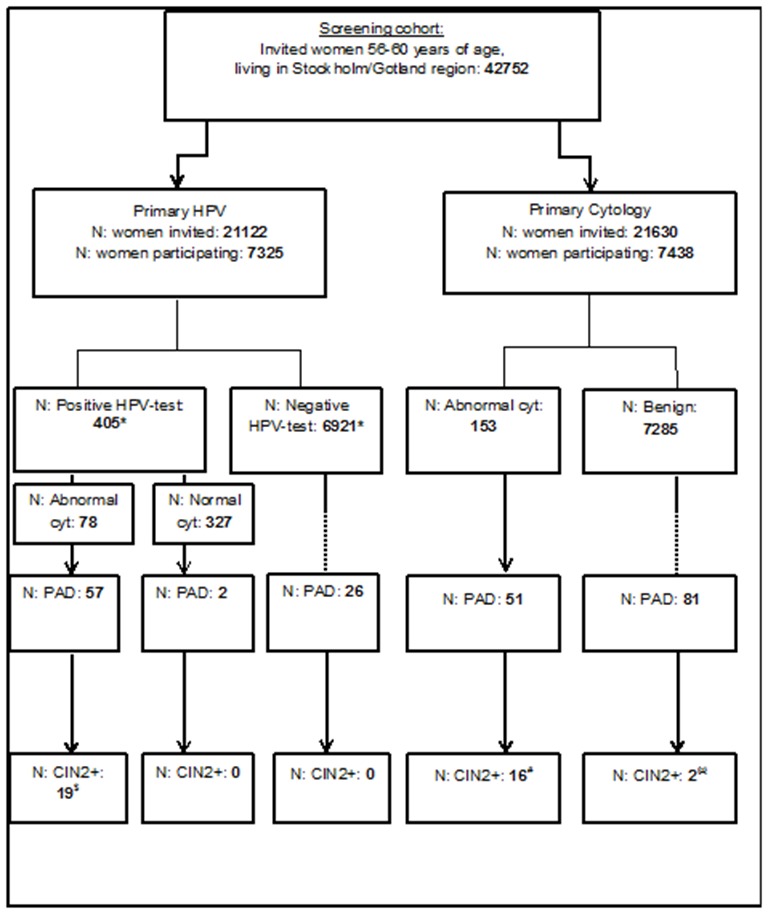

During January 2012–May 2014, the organised screening programme sent 42 752 blinded invitations with a prebooked appointment time to the women in the target age group. 7325 women attended in the HPV policy arm and 7438 women attended in the cytology arm. In the new policy, the population HPV prevalence was 5.5%, using an accredited HPV test (Cobas 4800). HPV16 prevalence was 1.0% (73/7325) and HPV18 prevalence was 0.3% (22/7325). In the HPV policy arm, 78/405 (19%) HPV-positive women were also cytology positive. There were 19 cases of CIN2+ in histopathology, all among women who were both HPV positive and cytology positive. The positive predictive value for CIN2+ in this group was 33.3% (19/57). In the cytology policy, 153 women were cytology positive and there were 18 cases of CIN2+ in histopathology. Both the total number of cervical biopsies and the number of cervical biopsies with benign histopathology were much lower in thepositive predictive value policy (49 benign, 87 total vs 105 benign, 132 total).

Conclusion

Primary HPV screening had a similar detection rate for CIN2+ as cytology-based screening, already before follow-up of HPV-positive, cytology-negative women with new HPV test and referral of women with persistence.

Trial registration number

Keywords: HPV primary screening, cervical cancer, organised screening programme

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was performed within an organised cervical cancer screening programme.

The randomised policy was evaluated with comprehensive registry linkages, providing population-based and complete data.

The study contributes to the limited information available on experiences of real-life implementation of HPV screening.

Limitations include a relatively short follow-up time, resulting in that most women with HPV persistence are not yet referred for clinical follow-up.

How women perceive the information about HPV was not investigated and needs to be further evaluated.

Introduction

Cervical screening using cytology has resulted in a marked reduction in cervical cancer incidence and mortality. Infection with oncogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV) is a necessary risk factor for the development of cervical cancer and primary HPV DNA screening has a higher sensitivity for detection of the precursor lesions of cervical cancer than cytology.1–4

However, HPV DNA testing will also detect recent infections that are likely to clear spontaneously. Major trials of HPV-based screening have used triaging of HPV-positive women with cytology, follow-up of HPV-positive/Cytology-negative women with a new HPV test and referral of women who are HPV+/HPV+ (persistently positive for HPV).5 International guidelines recommend against referring HPV-positive women without triaging using cytology.6

Today, a large part of cervical cancers develop in women aged 60 and over, where no screening is offered. A negative HPV test before exiting the programme is expected to give a longer lasting protection for cervical cancer than a negative cytology test. As HPV prevalences are age dependent, with lower prevalence among the oldest, it is likely that the age group 56–60 could be a suitable age group for piloting of implementation of primary HPV screening as health gains are expected, but the numbers of HPV-positive women for work-up would be comparatively small.

Already in 2008, European guidelines recommended that HPV testing can be adopted as a primary screening tool, provided that it is implemented in a carefully controlled manner that can be evaluated.6 The Randomized Healthcare Policy7 (RHP) was specifically mentioned as a recommended study design for a carefully controlled implementation that can be reliably evaluated.6

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether implementation of primary HPV screening in the organised screening programme for cervical cancer has at least the same cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) detection rate (safety) as cytology-based screening when implemented in real life.

Materials and methods

The cervical cancer screening programme in the Stockholm-Gotland region of Sweden invites women to screening at 3-year intervals between ages 23 and 50 and 5-year intervals between ages 51 and 60 (age is defined by birth year). The population coverage of being tested is high: 74.4% of resident women in the target ages are tested according to recommendations. Women who do not attend the appointment in the invitation letter are invited again next year, resulting in that never-attending women will during their ages 23–64 have been invited >40 times. Thus, less than half of all invitations are ‘primary’ invitations to regularly attending women and more than half of all invitations are reminder invitations to previously non-attending women. Population test coverage should thus not be confused with invitation attendance rate, which (because of the high proportion of reminder invitations to non-attenders) is about 35%.

There are no particular rules with regard to the last screening test—the rules for follow-up of that test are just the same as for all other tests. There is globally a discussion on the usefulness of more stringent rules for the last, exit test, but this has not yet been implemented in our population.

During January 2012 to May 2014, the resident women aged 56 to 60 who were invited to their last screening were randomised to two different screening policies: (1) primary cytology with HPV test as triage for women with low-grade cytology (atypical squamous cell of uncertain significance (ASCUS) and CIN1/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)) (old policy) or primary HPV test with triaging by cytology of HPV-positive women (new policy) (figure 1, study population). Information about the randomised implementation of HPV testing in the organised screening programme was sent out to all eligible resident women as part of the invitation to participate in the screening programme. Before the new policy was piloted, the protocol had been discussed in both the regional committee of specialist physicians in gynaecology and in a national hearing and found to be in accordance with the current scientific evidence. The RHP protocol was approved by the regional ethics committee (REC) in Stockholm (Decision number 2011/1298-31/3). The act of participating at the screening visit the woman had been invited to was, by the REC, regarded as consent for participation in the programme. The RHP is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (registration number NCT01511328). The current report describes the pilot phase of the RHP, which was designed to have a statistical power of 80% at a statistical significance level of 5%, assuming a constant rate for actual CIN2+ incidence in each group and a similar sensitivity in each group (80% actual sensitivity) and a target to show non-inferiority with a lower threshold of 80%.

Figure 1.

Study chart. *One woman had two samples taken, one negative and one positive for HPV. †Constitutes 11 women with CIN3, 6 with CIN2, 1 woman with CIN2/3 (exact grading not given) and 1 woman with invasive cervical cancer. ‡Constitutes eight women with CIN3 and eight women with CIN2. §Two women with invasive cervical cancer. CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade; HPV, human papillomavirus; PAD, cervical histopathology.

During the study period, 42 752 invitations were sent out to eligible resident women in the age group 56–60 years of age from the organised cancer screening programme. Randomisation to the two different screening policies used the last control digit in the personal identification number (PIN) of the women. 7438 women attended primary cytology screening, whereas 7325 women attended primary HPV screening. The same invitation letter, informing about the randomised policy, was sent to all women.

Samples were collected by trained midwives at the same, about 60, maternity care units as already being contracted as screening stations by the organised programme. All samples were taken using the same liquid-based cytology system (ThinPrep, Hologic, Boxborough, Massachusetts USA), where the cervical brush of the system was put in a standard test tube filled with PreservCyt media. The samples were collected identically, regardless of which primary screening test that would be used.

HPV testing was performed using the Cobas 4800 HPV Test (Roche Molecular Systems, South Branchburg, New Jersey, USA). The HPV types tested for were: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68. The Cobas system reports the tests as HPV16 positive, HPV18 positive and other high-risk HPV positive. All HPV-positive samples (regardless of HPV type) were subjected to reflex cytology. Samples with invalid results were retested once, if still invalid a new sample was taken. The same notification letters about cytology results as already used by the programme were used in this RHP. The notification letter to HPV-positive/Cyt-negative women reported that there was virus in the sample, but that the cytology was normal. It was further stated that this is regarded as a normal finding as long as the cytology is normal, but that an invitation to a repeat HPV and cytology test would follow after a year (or after 3 years, see below). In May 2013, new evidence from a joint European randomised trial indicated that Cyt-negative women were adequately protected against cervical cancer for 3 years5 and the interval for retesting of HPV-positive/Cyt-negative women was extended to 3 years. The European trial did not specify duration of adequate protection for cytology-negative women by age group5 and sampling from the transformation zone may be more difficult among older women. However, the duration of protection of cytology negativity is well known to be at least as long in older age groups, as for example reflected in the fact that many countries have longer screening intervals for older women (Sweden for example: www.socialstyrelsen.se), and Sweden therefore considered it to be conservative (safe) to use a 3-year interval in all age groups.

In the cytology arm, the samples were prepared for the cytological examination according to current programme standards. Clinical follow-up was exactly the same for both arms, both regarding cytology (including the combination of low-grade cytology/HPV positivity) and histopathology. The guidelines for clinical management were the same as routinely used in Sweden. Briefly, there is judgement of the transformation zone for visibility, maturation and epithelial changes. Application of 5% acetic acid assists in identifying undifferentiated epithelia or inflammation as well as true CIN. The dimension and borderline of an abnormal area is assessed by application of 5% potassium iodine to the ectocervix. All acetowhite areas, including metaplasia (undifferentiated epithelium), inflammation and neoplasia are biopsied. In case of incomplete colposcopy, several alternatives may be chosen, including repeat cytology, endocervical cytology or diagnostic conisation.8 As the cervical cancer-preventive effect of the Swedish cervical screening programme is among the best in the world,6 particularly for women who have actually participated, there is evidence to indicate that the clinical management is adequate.

HPV policy

Women who were high-risk HPV positive and had abnormal cytology were followed up according to the already established guidelines for follow-up of cytology (same as in the cytology arm). Those that were highrisk-HPV positive with normal cytology were followed up with another HPV test at an extra visit 12 months later or, from May 2013, 3 years later. If HPV persistent (positive for the same HPV types. Women positive for ‘Other HPV’ in the Cobas 4800 test had a second HPV test with complete HPV typing (Luminex) to determine if there was indeed type-specific persistence) they were referred to colposcopy. For the whole Stockholm-Gotland region, management of women with HPV persistence was centralised to a single experienced gynaecologist.

Cytology policy

Women with CIN2+ in primary cytology were always referred to colposcopy. Those with low-grade cytological abnormalities (ASCUS or LSIL (CIN1)) were triaged with HPV testing. If HPV positive, they were referred to colposcopy. If HPV negative, they were invited 1 year later for a new smear.

We used the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry to retrieve the information on all cytology and histology results of the participating women. The registry contains information on all cervical smears and all cervical biopsies taken in all counties in Sweden, resulting in that also smears and biopsies from women who relocated are detected. The structure, operation and completeness of the registry has been described.9 Please observe that, since the registry contains all data, a subsequent test could be taken for other reasons than the result of a previous test.

Results

There were 42 752 screening invitations with appointments sent out to all resident women in the target area who did not yet have a smear taken according to recommendations (table 1). As reminder invitations continue to be sent every year to non-attending women, the majority of invitations are reminder invitations sent to previously non-attending women. Thus, although the programme has high population test coverage (74.4%) the proportion of invited women who attend each invitation is about 35% (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women in the intervention and control arm

| Primary HPV policy | Primary cytology policy | |

| Invited women | 21 122 | 21 630 |

| Attending women | 7325 (34.7%) | 7438 (34.4%) |

| Referral rate to histopathology | 59 (0.8%) | 51 (0.7%) |

| Women with CIN2+ in histopathology | 19 | 18 |

| Low-grade lesions (CIN1) in histopathology | 17 | 9 |

| Benign histopathologies (any histopathological diagnosis of lower severity than CIN1). | 49 | 105 |

CIN1/CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1/grade 2 or worse; HPV, human papillomavirus.

The HPV prevalence in the population was 5.5% (405 women/7325 attending women)(table 2). The HPV16 prevalence was 1% and HPV18 prevalence was 0.3%. All 405 HPV-positive samples had a reflex cytology triage. Seventy-eight out of 405 HPV-positive women (19.3%) had an abnormal cytology (table 2).

Table 2.

Women attending primary HPV screening

| Primary HPV | |

| Screened women | 7325 |

| HPV positive | 405 (5.5%) |

| HPV positive with abnormal cytology | 78 |

| Histopathologies (HPV positive/all) | 59/85 |

| CIN2+ histopathologies (HPV positive/all) | 19/19 |

| CIN1 histopathology (HPV positive/all) | 16/17 |

| Benign histopathologies (HPV positive/all) | 24/49 |

CIN1/CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1/grade 2 or worse; HPV, human papillomavirus.

In the cytology policy, 153/7438 attending women had an abnormal cytology (table 3). Out of these, 134 had ASCUS/LSIL and were tested for HPV. Forty-three women tested positive for HPV (seven were positive for HPV16 and four for HPV18). Among all the women in the cytology arm, 132 women had a cervical biopsy with histology. In 18/132 biopsies, there was a CIN2+ lesion (figure 1 and table 3). The detection rate of CIN2+ was similar in the two arms (OR 1.07), but the 95% CI was wide (0.56 to 2.04) and completion of the final phase of the study will be needed to ascertain non-inferiority.

Table 3.

Women attending primary cytology screening

| Primary cytology | |

| Screened women | 7438 |

| Women with abnormal cytology | 153 |

| HPV test of women with abnormal cytology | 134 |

| HPV positive women with abnormal cytology | 43 |

| Histopathologies (abnormal cytology/all) | 51/132 |

| CIN2+ in histopathology (abnormal cytology/all) | 16/18 |

| CIN1 histopathology (abnormal cytology/all) | 8/9 |

| Benign histopathologies (abnormal cytology/all) | 27/105 |

CIN1/CIN2+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1/grade 2 or worse; HPV, human papillomavirus.

There was a large number of cervical histopathologies taken from women who had had a normal cytology (about 1% of the women), almost always with benign histopathological diagnoses (figure 1). This is a real-life study with comprehensive follow-up of all cervical events occurring for all women in the RHP. The medical records of these women were reviewed. For two women, no explanation could be found why a cervical histopathology had been taken. For the other women, there had been an abnormal cytology registered at another bodily site (vulva, vagina or endometrium).

The current study concerned cervical screening and cytologies and histopathologies taken outside of the cervix were thus not part of the study. But the study protocol included assessment of all cervical cytologies and histopathologies among randomised women, regardless of the reason for taking the tests. As real-life cervical screening can result in that some smears from non-cervical sites are also taken, cervical biopsies can result from abnormalities in non-cervical smears. This activity appeared to be less common in the HPV policy, resulting in lower numbers of cervical biopsies in the HPV policy.

Discussion

The current study has implemented and evaluated primary HPV-based screening with triaging using cytology within a real-life organised cervical screening programme. Primary HPV-based screening with triaging using cytology is since 2015 the main recommended screening algorithm, from both the WHO, the EU6 and the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (www.socialstyrelsen.se). In the age group where the new policy was first implemented (ages 56–60), we did not notice any adverse events that might have been expected (for example reduced adherence to follow-up induced by anxiety, etc), and we conclude that the new policy was acceptable to the population.

The exact population-based HPV prevalences in this age group (with the HPV test used) was not known before, but the 5.5% prevalence was approximately as expected. For example, in a large Danish cohort study, across all age groups, 898 of 4413 (20.3%) women with normal cytology were HPV DNA positive by Cobas 4800. This proportion decreased from 33.9% in women aged 23–29 years to 18.6% at age 30–39 years and 6.0% at age 50–65 years.10 The HPV test is performed using laboratory automation and the amount of personnel time required and costs was substantially reduced.

The number of primary referrals for gynaecological follow-up was substantially reduced (to about half), but the yield of histopathology-verified CIN2+ was about the same, indicating an improved specificity of the screening programme. HPV screening is expected to result in an increased sensitivity for CIN2+, but only after cytology-negative women with HPV persistence have also been referred. As HPV-positive/Cyt-negative women are only retested for HPV after 3 years, the results of these referrals will not appear until about 2 years from now. HPV persistence after 3 years is reported to be about 30% and we can thus expect that about 100 women of the 305 HPV-positive/Cyt-negative women will ultimately be referred. The total amount of referrals induced by HPV screening is thus expected to eventually be somewhat larger than, but comparable to, the amount of referrals induced by cytology-based screening. In this context, it should be noted that when a new screening test is first introduced, there is a temporary increase in screen-detected lesions that were prevalent when the screening was started. Subsequent rounds of screening will, to a larger extent, detect lesions that occurred since the last screening round (incident lesions). The proportion of the lesions detected by HPV-based screening, but not by cytology, that are prevalent or incident is not well known, although estimates have been provided by some clinical trials that have run for several screening rounds.

The present study investigated the effects of a real-life use of HPV-based screening. One of the effects that is seen by a real-life study (but not by a randomised clinical trial, that is typically double blinded) is the effect that knowledge of the test results may have. It is for example likely that cytotechnicians reading slides known to be HPV positive may have an increased attention, reducing the likelihood for false negative results (so-called reader error). The fact that more abnormal cytologies (confer tables 1 and 2) were detected in the HPV screening arm may be a reflection of this. Conversely, it may seem surprising that the same yield of CIN2+ is obtained in both arms, even though both arms used cytology results for referral and the cytology arm performed 95% less cytologies—at least some CIN2+ lesions would have been expected to be detected by reading HPV-negative smears. Possibly, the effects of non-detection of HPV-negative CIN2+ and reduced reader error because of more focused cytology readings may have been of about the same magnitude resulting in similar yields.

The substantial amount of cervical histopathologies taken among women with normal cervical cytology was largely attributable to prior cytologies with abnormal results, taken from non-cervical sites. Screening for diseases of the vulva, vagina or endometrium is not an aim of the cervical screening programme. As for example endometrial cancer is known to be HPV negative, endometrial cancers will no longer be detected by the cervical screening programme when it is based on HPV detection. Reduction of cervical biopsies taken after smears from non-cervical sites thus appears to be a likely benefit of the switch to HPV-based screening. Evaluation of whether cervical screening has indeed had any health benefit with regard to endometrial cancer appears to be a research priority.

Strengths of the study

This study was performed within an organised cervical cancer screening programme with high-population coverage, and the results are therefore generalisable to a real-life population-based cervical screening programme, including exactly the same strategy for reaching non-attending women (repeat reminder invitations). The attending women will therefore constitute the same mix of women attending ‘primary’ invitations and women attending reminder invitations as seen in the real-life screening programme.

The randomised policy was evaluated with comprehensive registry linkages, providing population-based and complete data. Because Sweden has a population-based system for registration of smears and biopsies, all results are included even if women chose to attend healthcare to which they were not referred to (eg, private healthcare). This reduces the risk for selection biases incurred by losses to follow-up.

Limitations of the study

Limitations include a relatively short follow-up time, resulting in that most women with HPV persistence are not yet referred. Although longer follow-up to include the results of referrals of women with HPV persistence (but normal cytology) is expected to increase sensitivity of HPV screening, studies nested in a real-life screening programme (where continued invitations and testing is taking place) will face increasing difficulties in ascertaining exactly which smear induced which biopsy. From a programme perspective, providing the overall results from the first 2 years of organised HPV screening is therefore considered more useful than providing the ultimate sensitivity estimates. Furthermore, these estimates are well known from many previous studies in the research setting.2 5 11–15

Another limitation is that we did not follow-up how women perceived the information about HPV. This needs to be further evaluated, but a conclusion of the current study is that population-based HPV screened appeared to be generally acceptable to the population.

Comparison with others

The study contributes to the limited information available on experiences of real-life implementation of HPV screening. Although a very large number of studies have evaluated HPV screening in the research setting, also in longitudinally followed randomised controlled trials with invasive cancer as endpoint,5 15 there are only few studies reporting on HPV screening in a real-life programme. An RHP in Finland had a rather similar study design16 except that a broad implementation in all relevant ages was introduced at the outset. We chose a more cautious implementation with a relatively small RHP restricted only to a small age group. A study on the introduction of HPV screening in central Italy reported a doubled increase in detection rates and a fourfold increase in referral rates, but with a protocol where HPV-positive, cytology-negative women were retested after 1 year.17 The authors suggest that more conservative protocols are needed. Indeed, Dijkstra et al reported that HPV-positive, cytology-negative women can safely be referred to late retesting 5 years later.18

Our study implies that HPV screening will have similar safety as cytology-based screening in the first years after introduction, even before referring HPV-positive cytology-negative women. The issue of how to manage this group of women may depend on available resources, but it seems clear that aggressive management is not required from a safety perspective.

The difference between a real-life study and a research study is clearly exemplified by the noteworthy number of screened women who are referred for clinical follow-up, but never have a biopsy taken (confer figure 1). In the research setting, there is typically near-complete adherence to guidelines. In the real-life setting, there are often deviations from guidelines. For example, the most recent assessment found that there are annually about 160 women in Sweden with a high-grade abnormality in cytology, but no subsequent biopsy9 which confers a very high risk for cervical cancer development.

Caution should be exerted in interpreting our experience that the total cost of screening was reduced with HPV screening. Costs of testing are highly dependent on purchasing, efficiency of laboratory organisation and testing volumes used, which may be different in other settings.

In conclusion, the current randomised healthcare policy finds that HPV-based screening is readily possible to implement, using the existing resources for the organised programme and for the clinical follow-up. Primary HPV screening had, even before follow-up of HPV-positive, cytology-negative women with new HPV test and referral of women with persistence, a similar detection rate for CIN2+ as cytology-based screening. The 2015 Swedish cervical screening guidelines (www.socialstyrelsen.se) recommend HPV-based screening for women 30–64 years of age and the results of the current study support an extension of HPV screening using the protocol of this study to the entire target group 30–64 years of age.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HL aquired HPV testing data, coordinated the project and the writing of the paper. CE assisted in planning of the project and its quality assurance. KME assisted with registry linkages and interpretation of data. ACT coordinated the sample taking stations and assisted in planning of the project. MH performed registry linkages. KE performed the clinical follow-up of HPV-positive women, assisted with planning of the project. ST was the coordinator of the screening programme, participated in project planning, was responsible for implementation and provided supervision. JD designed the study and provided supervision. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript by providing important intellectual input.

Funding: This study was supported by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: The act of participating at the screening visit the woman had been invited to was, by the REC, regarded as consent for participation in the programme.

Ethics approval: Regional ethics committee (REC) in Stockholm.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Individual-level data will be shared on request, to be sent to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, et al. Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine 2012;30(Suppl 5):F88–F99. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1589–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa073204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Results at recruitment from a randomized controlled trial comparing human papillomavirus testing alone with conventional cytology as the primary cervical cancer screening test. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:492–501. 10.1093/jnci/djn065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elfström KM, Smelov V, Johansson AL, et al. Long term duration of protective effect for HPV negative women: follow-up of primary HPV screening randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014;348:g130 10.1136/bmj.g130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014;383:524–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, et al. , IARC. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical Cancer screening. 2nd ed Belgium: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hakama M, Malila N, Dillner J. Randomised health services studies. Int J Cancer 2012;131:2898–902. 10.1002/ijc.27561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, et al. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elfström KM, Sparén P, Olausson P, et al. Registry-based assessment of the status of cervical screening in Sweden. J Med Screen 2016;23:217–26. 10.1177/0969141316632023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Preisler S, Rebolj M, Untermann A, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in 5,072 consecutive cervical SurePath samples evaluated with the Roche cobas HPV real-time PCR assay. PLoS One 2013;8:e59765 10.1371/journal.pone.0059765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anttila A, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, Leinonen M, et al. Rate of cervical cancer, severe intraepithelial neoplasia, and adenocarcinoma in situ in primary HPV DNA screening with cytology triage: randomised study within organised screening programme. BMJ 2010;340:c1804 10.1136/bmj.c1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kitchener HC, Gilham C, Sargent A, et al. A comparison of HPV DNA testing and liquid based cytology over three rounds of primary cervical screening: extended follow up in the ARTISTIC trial. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:864–71. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:78–88. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70296-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:249–57. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1385–94. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lönnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ 2012;345:e7789 10.1136/bmj.e7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Passamonti B, Gustinucci D, Giorgi Rossi P, et al. Cervical human papilloma virus (HPV) DNA primary screening test: results of a population-based screening programme in central Italy. J Med Screen 2016. 10.1177/0969141316663580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dijkstra MG, van Zummeren M, Rozendaal L, et al. Safety of extending screening intervals beyond five years in cervical screening programmes with testing for high risk human papillomavirus: 14 year follow-up of population based randomised cohort in the Netherlands. BMJ 2016;355:i4924 10.1136/bmj.i4924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.