Abstract

Objective

To validate the Italian algorithm of attribution of neuropsychiatric (NP) events to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in an external international cohort of patients with SLE.

Methods

A retrospective cohort diagnostic accuracy design was followed. SLE patients attending three tertiary care lupus clinics, with one or more NP events, were included. The attribution algorithm, applied to the NP manifestations, considers four weighted items for each NP event: (1) time of onset of the event; (2) type of NP event (major vs minor), (3) concurrent non-SLE factors; (4) favouring factors. To maintain blinding, two independent teams of assessors from each centre evaluated all NP events: the first provided an attribution diagnosis on the basis of their own clinical judgement, assumed as the ‘gold standard’; the second applied the algorithm, which provides a probability score ranging from 0 to 10. The performance of the algorithm was evaluated by calculating the area under curve (AUC) of thereceiver operating characteristic curve.

Results

The study included 243 patients with SLE with at least one NP manifestation, for a total of 336 events. 285 (84.8%) NP events involved the central nervous system and 51 (15.2%) the peripheral nervous system. The attribution score for the first NP event showed good accuracy with an AUC of 0.893 (95% CI 0.849 to 0.937) using dichotomous outcomes for NPSLE (related vs uncertain/unrelated). The best single cut-off point to optimise classification of a first NPSLE-related event was≥7 (sensitivity 87.9%, specificity 82.6%). Satisfactory accuracy was observed also for subsequent NP events.

Conclusions

Validation exercise on an independent international cohort showed that the Italian attribution algorithm is a valid and reliable tool for the identification of NP events attributed to SLE.

Keywords: neuropsychiatric disorders, attribution algorithm, systemic lupus erythematosus, focal manifestation, diffuse manifestation, peripheral nervous system, central nervous system

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study follows a retrospective cohort design that could have influenced the proper attribution of neuropsychiatric (NP) events; nevertheless, the collection of data from selected centres with medical expertise in NP systemic lupus erythematosus may have favoured a homogeneous diagnostic approach.

The sample size is large and comprised of sufficient numbers of NP events observed in multiethnic patients.

Some rare NP events are poorly represented in our cohort making our results not fully generalisable to all NP events included in the American College of Rheumatology glossary.

INTRODUCTION

Neuropsychiatric (NP) involvement is one of the most complex manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), characterised by a wide heterogeneity of clinical events affecting the central (CNS), peripheral (PNS) and autonomic nervous systems.1 The phenomenology of NP involvement may include a variety of characteristics, such as NP events being focal or diffuse, acute or chronic, active or not active, single or multiple and synchronous or metachronous.2 3

In 1999, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) produced a standard nomenclature and set of case definitions for 19 NP syndromes (12 CNS and 7 PNS manifestations) known to occur in SLE. The ACR classification is considered a milestone in the field of NPSLE, providing definitions for each clinical NP syndrome; exclusion criteria, aimed to rule out NP events not directly related to SLE; associations, to consider potential concomitant or pre-existing confounding factors and a diagnostic work-up to assess each NP event.1 In this respect, the ACR classification provided a useful tool for patient selection in clinical studies, offering standardised definitions that are primarily intended to create well-defined and homogeneous cohorts of patients with NP involvement. However, up to date, the usefulness of ACR case definitions in clinical practice has proven to be of limited value; in fact, even if NP events (especially less specific ones, such as headaches, mood disorders, mild cognitive deficits or peripheral neuropathies not confirmed by electrophysiology4) have passed the ACR filter, it has been difficult to differentiate patients with NPSLE from those with NP manifestations not related to SLE5 and the final attribution still relies on the clinical judgement of experienced clinicians. Therefore, the optimal process to determine the attribution of NP events to SLE or other causes remains an unmet need.

In an attempt to address this issue, Monov and Monova proposed a model distinguishing major from minor or ‘common’ NP events.6 The latter were derived from a population-based study where the above-mentioned less specific NP events have been considered as never being confidently attributed to SLE, since they are also frequently observed in the general population.4 5 In this model, it was proposed that a diagnosis of NPSLE can be reached, provided the exclusion of other causes, in the presence of at least one of the major NP events or, alternatively, in the presence of minor NP events combined with additional diagnostic data (ie, neuroimaging, electrophysiology and laboratory abnormalities).6 Another attribution model, derived from the large SLE disease inception cohort recruited by the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC), has been proposed by Hanly et al.7 8 This model—with two different levels of stringency (models A and B)—is based on three simple rules that take into account: (1) the temporal relationship between the NP event and the diagnosis of SLE (model A: 6 months before to 15 months following SLE diagnosis, for a total period of 21 months; model B: within 10 years prior to SLE diagnosis and still present during the enrolment window), (2) the type of NP event (major or minor) and (3) a comprehensive list of exclusions/associations derived from the ACR case definitions for 19 NP syndromes.

In a recent study of a large cohort of Italian patients with SLE, we proposed and preliminarily validated a new algorithm, based on a probability score, to determine the attribution of NP events to SLE or to other causes.9 The objective of the present study was to validate the Italian attribution algorithm in an international cohort of patients with SLE and at least one NP event, as per the 1999 ACR case definitions.

METHODS

Study design

This study follows a retrospective cohort diagnostic accuracy design. Reporting complies with the ‘Standards for Reporting Diagnostic accuracy studies’ 2015 recommendations (see supplementary STARD checklist).10

Participants

The study included a validating set of selected patients with SLE attending three tertiary care clinics dedicated to the management of patients with SLE from 1982 to 2015 (Department of Rheumatology, Clinical Immunology and Allergy, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece; Medicine, State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil; Dalhousie University and Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada). Patients from each centre were selected if they satisfied the 1997 revised ACR classification criteria for SLE11 and had one or more NP events, as defined in the ACR case definitions of 19 NP syndromes. The local ethics committees approved the study.

Attribution algorithm and case definition

A similar methodology to the one used in our original study was adopted.9 A dedicated electronic record was created, including demographic data and the core set of items for classification. Briefly, the algorithm included four items: (1) the timing of onset of the NP event (ie, before, >6 months; concurrent, within 6 months or after SLE diagnosis); (2) the type of NP event (major vs minor or common, according to Ainiala et al 5); (3) the presence of confounding non-SLE factors (ie, ‘associations’ suggested in the glossary for the 1999 ACR case definitions); (4) the presence of ‘favouring factors’ (ie, supporting attribution). The first two items applied to all NP events; for items (3) and (4), lists of variables specific for each NP event (derived from the glossary for the ACR case definitions for 19 NP syndromes and supplemented by systematic literature review and expert opinion) were generated (see online supplementary materials S1 and S2) for the complete lists and supplementary material S3, table S1 for the weight assigned to each item by the expert panel).

To maintain blinding, all first NP events were evaluated by two independent teams of assessors from each centre, each of whom was assigned different tasks: the first provided an attribution diagnosis (related/uncertain/unrelated to SLE) on the basis of their own clinical judgement, using all of the information available in the patient record; the second applied the attribution algorithm described above, using the same available information.

We chose to analyse primarily the first NP events, for two main reasons: (a) to make results comparable to our original study and (b) in order to validate rules for attribution of the first NP event before applying them also to subsequent NP events, since the attribution of subsequent events could be influenced by the classification of the first event. To verify this point, we evaluated separately subsequent NP events.

Based on previously defined weights for each item,9 which sum up to a global score ranging from 0 to 10 points, two different attribution models were generated: an initial ‘a priori’ model, based on the weights assigned by a Delphi round expert consensus, and an updated version, based on both ‘a priori’ and ‘data-driven’ coefficients9 (see below for more details).

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the cohort are reported using descriptive statistics. Missing data were not imputed, and complete case analysis was performed. The international dataset has been evaluated separately and then compared and combined to the two previously published training and validating Italian cohorts (see online supplementary material S4 for members of the Italian Study Group on Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus of the Italian Society of Rheumatology), in order to perform a pooled analysis.9

bmjopen-2016-015546supp004.pdf (176.3KB, pdf)

The first analysis aimed to test discrimination of the previously reported algorithms (‘a priori’ and ‘updated’) on the international cohort. Discrimination was assessed with calculation of the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, using SLE-related NP events (ie, definite NPSLE) as positive outcomes and uncertain/unrelated as negative outcomes. The results from the international validating cohort were then compared with those of the training and validating Italian cohorts.

The second set of stratified analyses replicated the first, based on the type of NP event: major/minor, focal/diffuse, ischaemic/non-ischaemic and central/peripheral.

Further analyses replicated the process of adaptation of the a priori coefficient obtained by multivariate ordinal logistic models using importance weights to a priori and data-driven coefficients (3:1). These analyses were done in the new validating dataset and in the pooled data from all three cohorts. A final validated algorithm was defined based on robustness, discrimination and feasibility considerations.

Finally, based on the ROC tables using binary outcomes, the best threshold cut-off point for attribution, able to discriminate SLE-related (primary NPSLE) versus uncertain/not related NP events, was assessed in the international validating cohort and in the pooled dataset, based on the maximum proportion of correctly classified NPSLE cases. Other clinically relevant cut-off points with misclassification rates <10% were also defined. Results are presented as sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for each cut-off point. All analyses were performed using Stata V.11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

International validation

The study included 243 patients with SLE (178 from Heraklion, Greece; 53 from Campinas, Brazil and 12 from Nova Scotia, Canada) and at least one NP event for a total of 336 events. One hundred and ninety-seven patients (81.1%) were of European ancestry, 24 (9.9%) of African ancestry and 22 (9%) Hispanic; they were mainly women (219 women, 90.1%; 24 men, 9.9%), with a mean (SD) age at first NP event of 39.0 (13.9) years. Two hundred and eighty-five (84.8%) NP events involved the CNS and 51 (15.2%) events involved the PNS (table 1). Mood disorder was the most frequent manifestation (n=55, 16.4%), followed by headache (n=50, 14.9%) and cerebrovascular disease (n=38, 11.3%).

Table 1.

Distribution of neuropsychiatric events in the international cohort

| First, n (%) | Following, n (%) | All, n (%) | |

| PNS and CNS involvement | 243 (100) | 93 (100) | 336 (100) |

| CNS involvement | 202 (82.3) | 83 (89.2) | 285 (84.8) |

| Mood disorder | 43 (17.7) | 12 (12.9) | 55 (16.4) |

| Headache | 35 (14.4) | 15 (16.1) | 50 (14.9) |

| CVD | 33 (13.6) | 5 (5.4) | 38 (11.3) |

| Seizures | 22 (9.1) | 12 (12.9) | 34 (10.1) |

| Anxiety | 16 (6.6) | 2 (2.1) | 18 (5.4) |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 13 (5.3) | 20 (21.5) | 33 (9.8) |

| Psychosis | 11 (4.5) | 6 (6.5) | 17 (5.1) |

| MS-like syndrome | 9 (3.7) | 1 (1.08) | 10 (3) |

| Myelopathy | 8 (3.3) | 4 (4.3) | 12 (3.6) |

| Movement disorder | 5 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (1.8) |

| Acute confusional state | 5 (2.1) | 3 (3.2) | 8 (2.4) |

| Aseptic meningitis | 2 (0.8) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (1.2) |

| PNS involvement | 41 (17.7) | 10 (10.8) | 51 (15.2) |

| Cranial neuropathy | 15 (6.2) | 3 (3.2) | 18 (5.4) |

| Polyneuropathy | 10 (4.1) | 4 (4.3) | 14 (4.2) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 9 (3.7) | – | 9 (2.7) |

| Mononeuropathy | 4 (1.6) | 2 (2.1) | 6 (1.8) |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 3 (1.2) | – | 3 (0.9) |

| Autonomic neuropathy | – | – | – |

| Plexopathy | – | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Major/minor | 148/95 (60.9/39.1) | 64/29 (68.8/31.2) | 212/124 (63.1/36.9) |

| Focal/diffuse | 109/134 (44.9/55.1) | 61/32 (65.6/34.4) | 170/166 (50.6/49.4) |

| Central/peripheral | 202/41 (83.1/16.9) | 83/10 (89.2/10.8) | 287/49 (85.4/14.6) |

CNS, central nervous system; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; PNS, peripheral nervous system.

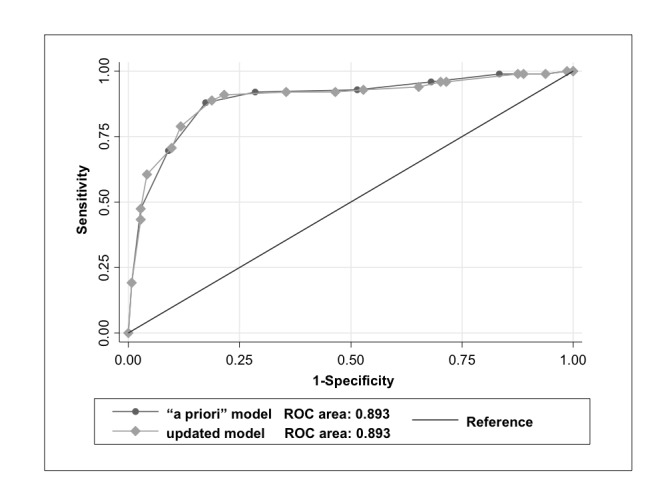

Applying the data driven and a priori coefficients (supplementary material S3, table S1), the ROC curve analysis related to the first NP event observed in the international cohort showed an AUC of 0.893 (95% CI 0.849 to 0.937) for the ‘a priori’ model and 0.892 (95% CI 0.847 to 0.937) for the ‘data driven’ model, using dichotomous outcomes (related vs uncertain/unrelated, figure 1), a performance comparable to the one previously observed in the training and validating cohorts (table 2).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using dichotomous outcomes (related vs uncertain/not related), for attribution of the first neuropsychiatric event observed in the international cohort.

Table 2.

Comparison of the accuracy of the ‘a priori’ and of the ‘updated’ algorithms for attribution of the first neuropsychiatric events in the three cohorts

| Cohort | No of pts | A priori (original) algorithm | Updated algorithm | |||

| AUC | (95% CI) | AUC | (95% CI) | p Value* | ||

| Cohort 1: Training 9 | 225 | 0.845 | 0.797 to 0.892 | 0.857 | 0.811 to 0.904 | 0.03 |

| Cohort 2: Italian validating9 | 209 | 0.818 | 0.759 to 0.876 | 0.818 | 0.759 to 0.876 | 1.0 |

| Cohort 3: International9 | 243 | 0.893 | 0.849 to 0.936 | 0.892 | 0.847 to 0.937 | 0.9 |

| p Value† | 0.10 | 0.13 | ||||

AUC, area under curve.

*Intracohorts comparison.

†Intercohorts comparison.

bmjopen-2016-015546supp003.pdf (236.4KB, pdf)

The analysis of the ‘data-driven’ coefficients, derived from the multivariate ordinal logistic model, and the ‘a priori’ coefficients on the pooled data led to a final updated model where the weight assigned to each item was highly consistent with the assigned ‘a priori’ coefficient (see online supplementary material S3, table S1).

The ROC curve analysis stratified for the timing of onset of the first NP events, before, concomitant or after the diagnosis of SLE, showed an AUC of 0.68 (95% CI 0.12 to 1.00), 0.78 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.92) and 0.85 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.92), respectively. A similar analysis applied to subsequent NP events showed again a good performance with an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.88) (see details in online supplementary material S3, table S2).

Taking into account a global score ranging from 0 to 10, the best single cut-off score for correct classification of a first NPSLE-related event in the international cohort was 7 (table 3) with a sensitivity of 87.9%, specificity of 82.64%, a PPV of 77.68% and a NPV of 90.84%. The best discriminating cut-off point was also assessed in the pooled cohorts, where the final score ≥7 was confirmed as the single best attribution threshold for a correct classification of the first SLE-related NP event (sensitivity 71.2%, specificity 84.5%, PPV 82.9%, NPV 73.6%); again, in the pooled cohort, a score ≥8 was the cut-off point associated with a misclassification probability <10% (sensitivity 47.5%, specificity 97.2%, PPV 92.1%, NPV 72.9%), while a score ≤2 had a NPV of 90% for a SLE-related event (see online supplementary material S3, table S3). Including subsequent NP events, the same cut-off points have been deemed applicable as best discrimination threshold.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for each defined cut-point derived from the application of the attribution algorithm (using ‘a priori’ coefficients) to the first NP event observed in the international cohort

| Cut-point | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Correctly classified (%) | LR+ | LR− | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

| (≥0) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 40.7 | 1 | 40.7 | ||

| (≥1) | 100.0 | 1.4 | 41.6 | 1.0141 | 0 | 41.1 | 100.0 |

| (≥2) | 99.0 | 6.2 | 44.0 | 1.0559 | 0.1616 | 42.1 | 90.0 |

| (≥3) | 99.0 | 16.7 | 50.2 | 1.1879 | 0.0606 | 45.0 | 96.0 |

| (≥4) | 96.0 | 31.9 | 58.0 | 1.41 | 0.1265 | 49.2 | 92.0 |

| (≥5) | 92.9 | 48.6 | 66.7 | 1.8084 | 0.1455 | 55.4 | 90.9 |

| (≥6) | 91.9 | 71.5 | 79.8 | 3.2284 | 0.113 | 68.9 | 92.8 |

| (≥7) | 87.9 | 82.6 | 84.8 | 5.0618 | 0.1467 | 77.7 | 90.8 |

| (≥8) | 69.7 | 91.0 | 82.3 | 7.7203 | 0.3331 | 84.1 | 81.4 |

| (≥9) | 47.5 | 97.2 | 76.9 | 17.0909 | 0.5403 | 92.1 | 72.9 |

| (≥10) | 19.2 | 99.3 | 66.7 | 27.6364 | 0.8137 | 95.0 | 64.1 |

| (>10) | 0.0 | 100.0 | 59.3 | 1 | 59.3 |

LR, likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; NP, neuropsychiatric; PPV, positive predictive value.

Comparison of the performance of the algorithm in the three patient cohorts

The overall performance of the attribution algorithm applied to the three different cohorts showed some differences, being the results obtained in the international cohort even better, to the one of the original study (table 2). To investigate the reasons for such a different performance, we further analysed the composition of the cohorts regarding the typology of the included NP events, since their heterogeneity could have impacted on the results.

As shown in table 4, the three cohorts have a different prevalence of individual NP events (table 4): the international cohort had a higher prevalence of major, focal and peripheral NP events than the two previous cohorts.

Table 4.

Prevalence rate of different NP events and performance of the algorithm in the international cohorts and comparison with the training and validating cohort

| Type of event | Training cohort (1) | Validating cohort (2) | International cohort (3) | p Values* | |||

| N (%) | AUC (95% CI) | N (%) | AUC (95% CI) | N (%) | AUC (95% CI) | ||

| Minor | 136 (60.4) | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.84) | 104 (50.2) | 0.73 (0.62 to 0.83) | 95 (60.9) | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.90) | 0.88 |

| Major | 89 (39.6) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | 105 (49.8) | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.91) | 148 (39.1) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.94) | 0.09 |

| p Values† | 0.0006 | 0.12 | 0.06 | ||||

| Focal | 76 (33.8) | 0.90 (0.83 to 0.97) | 83 (39.7) | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.92) | 109 (44.9) | 0.89 (0.84 to 0.96) | 0.31 |

| Diffuse | 149 (66.2) | 0.81 (0.76 to 0.88) | 122 (60.3) | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.87) | 134 (55.1) | 0.83 (0.74 to 0.92) | 0.78 |

| p Values† | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.11 | ||||

| Ischaemic | 38 (16.7) | 0.87 (0.75 to 0.98) | 28 (13.4) | 0.82 (0.62 to 1.00) | 33 (13.6) | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.00) | 0.92 |

| Non-ischaemic/ inflammatory | 187 (83.3) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.89) | 181 (86.6) | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.88) | 210 (86.4) | 0.89 (0.84 to 0.94) | 0.14 |

| p Values† | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.59 | ||||

| Central | 200 (88.9) | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.90) | 192 (91.9) | 0.81 (0.75 to 0.87) | 202 (83.1) | 0.89 (0.84 to 0.94) | 0.16 |

| Peripheral | 25 (11.1) | Not applicable | 17 (8.1) | 0.89 (0.74 to 1.00) | 41 (16.9) | 0.88 (0.76 to 0.98) | 0.83 |

| p Values† | - | 0.27 | 0.87 | ||||

*p Values intercohorts comparison between the AUC calculated for the different type of the event.

†p Values intracohort comparison between the AUC calculated for the different type of the event.

AUC, area under curve; NP, neuropsychiatric.

Stratified analyses based on the type of NP event: major/minor, focal/diffuse, ischaemic/non-ischaemic and central/peripheral

The performance of the algorithm was evaluated separately by testing the events clustered by type of event. Comparing the accuracy of ROC curve in minor/major, focal/diffuse, ischaemic/non-ischaemic and peripheral/central NP events, there were no statistically significant differences in performance among the three cohorts, although, as expected, the accuracy of the model was better for major and focal events and similar for ischaemic, non-ischaemic, central and peripheral manifestations (table 4).

DISCUSSION

Recently, on behalf of the Study Group for NPSLE of the Italian Society of Rheumatology, an attribution model based on a simple numerical algorithm (ranging from 0 to 10) and derived from a robust statistical evaluation and large dataset was proposed. The original algorithm was tested on a single-centre training cohort of patients with SLE and then validated on an independent Italian cohort demonstrating good performance in terms of sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV when compared with expert clinical judgement (the current ‘gold’ reference standard). To further validate this algorithm, taking also into account differences in ethnicity, we have tested its performance in a third independent international cohort including patients with one or more NP events, as per the 1999 ACR case definitions.

The first analysis (based on ‘a priori’ defined and ‘updated’ coefficients), aimed to test the discrimination power of the aforementioned algorithm on the external international cohort, demonstrated an overall performance of the algorithm highly comparable to our original study (figure 1), confirming its high reliability. Further analyses replicated the process of adaptation of the a priori coefficients using data-driven results of a) the new validating international cohort and b) the overall pooled dataset (all three cohorts) to validate the original model composed by predefined and weighted coefficients.9

Based on the ROC tables and using binary outcomes, the best cut-off for discrimination (ie, attribution threshold) was assessed in the international validating set and in the pooled dataset. A total score ≥7 (range from 0 to 10) identified the maximum proportion of correctly classified NPSLE cases (both first and subsequent NP events). Compared with the lower cut-off point we found in our original paper (≥6),9 this result is worthy of comment. First, there were differences in the composition of the international and the original cohorts, with particular regard to the distribution of major NP events. Given the structure of the algorithm, higher scores are assigned to these types of NP events.12 In this way, 7 is the maximum score that can be reached by applying the model for a minor event. This implies a higher ‘attribution threshold’ for minor NP events and, consequently, only a limited percentage of these events will be attributed to SLE using the algorithm in its current version. Accordingly, a greater prevalence of minor or diffuse events would influence the final performance of the attribution algorithm, which is derived from the cohort wherein it is applied. However, although the different composition of the individual cohorts (see table 4) may have influenced the definition of the ‘attribution threshold’, merging data of all three cohorts has balanced the proportion of major and minor events, thus making the newly identified cut-point more reliable for attribution. Interestingly, in a recent study by Fanouriakis et al,12 a similar result has been reached. In that study, different models of attribution, including our own, have been tested against ‘clinical judgement’ in an independent and ‘real life’ cohort of patients with SLE with NP involvement; applying our algorithm, the best performing cut-off point to ensure the discrimination between primary NPSLE from NP events not related to SLE was ≥7, that is, the same as the one we found in the present validation study.

In our opinion, the ‘small window’ of attribution for minor events is not a drawback; rather, it is in keeping with the evolution of the concept of NPSLE itself. In fact, inclusion of these minor events has substantially influenced the prevalence of NPSLE, especially in the past,13–16 while in more recent years, prospective studies derived from the SLICC inception cohort have challenged this concept of NPSLE, demonstrating that such events correlate poorly with conventional measures of SLE disease activity, autoantibodies and lupus specific therapies. For this reason, these NP events require a more careful and rigorous clinical evaluation in order to determine the correct attribution.17–19 For example, in the SLICC cohort, out of a total of 1732 patients, 17.8% had headache within the enrolment window, migraine in 60.7%, tension in 38.6%, intractable non-specific in 7.1%, cluster in 2.6% and intracranial hypertension in 1.0%.18 Although the prevalence of headache rose to 58% by 10 years, only 26 patients (1.5% of the cohort) experienced ‘lupus headache’ over the entire study, reported as a variable in the SLEDAI-2K20 at annual assessments.19 Hanly et al also reported that mood disorders occurred in 12.7% of 1827 patients in the SLICC cohort, and a little more than a third of the total (98 events, 38.3%) were attributed to SLE.18

As a result of these and other studies, the frequency of NPSLE has been re-evaluated.6 8 9 However, one must not forget that mood disorders, headache and mild cognitive deficits, all frequently observed in patients with SLE, depend heavily on clinical assessment of mainly subjective symptoms; not surprisingly, it is in these cases that we observed the worst performance of the model, when compared with the current ‘gold standard’, that is, the judgement of experienced physicians. Nevertheless, given the intrinsic uncertainty of the diagnosis for some NP manifestations, especially the common minor NP events, to reach a confident diagnosis of primary NPSLE is sometimes only presumptive, despite the efforts to improve the tools available to the clinician. For this reason, the categorisation of NPSLE events based on a quantitative score could ensure a more standardised and consistent approach to the attribution of NP events in future studies of NPSLE.21 Moreover, the model has characteristics of flexibility and versatility that could be adapted to the setting in which a clinician operates. It is possible to modulate the single cut-off in relation to clinical contingency, choosing from time to time sensitivity over specificity or vice versa, remembering that even more stringent cut-points (ie, ≤2 and ≥8 meaning that the NP event has a high chance to be unrelated or related to SLE, respectively) are also associated with a—relatively low—probability of misclassification (10%). It may be that more stringent cut-points could be tested as a ‘therapeutic threshold’ (ie, to treat or not to treat). On this topic, a prospective study is already underway.

There are several study limitations that should be mentioned. First, the use of a retrospective design is a weakness that could have influenced the proper attribution of some NP events, thus at risk of bias, due to incomplete data collection, especially for NP events observed before the publication of the ACR nomenclature. However, a supplementary analysis restricted to the subset of events observed after 1999 gave similar results to those obtained using all first NP events (data not shown). A second limitation is the low number of some rare NP events, making our results not fully generalisable to all NP events included in the ACR glossary. Finally, this model currently has to be considered as confidently tested and validated for the evaluation and attribution of the first NP event since the attribution of subsequent events could be influenced by history or recurrence of NP manifestations in the same patient, recognised as a risk factor for primary NPSLE involvement.17 18 22–26 However, when the algorithm was applied to subsequent NP events, it demonstrated a similar and satisfactory performance as for the first one, especially for antecedent events unrelated to SLE.

In summary, in this study, we confirmed that the Italian attribution algorithm is a valid and robust tool for the correct identification of cases with NPSLE, with a validated score for attribution of NP events ≥7 (in a scale ranging from 0 to 10). The ‘a priori score’ originally defined by the expert panel to weigh the single items included in the attribution model was shown to be consistent and accurate and confirmed by the data-driven analysis of both an external international cohort and of the pooled cohorts. In a medical setting as complex as NPSLE, we do not believe that our model should substitute the clinical judgement provided by experienced and multidisciplinary teams, but rather, it could assist them in the attribution process. The categorisation of patients with NPSLE based on a quantitative, reliable and validated probability score might provide a more standardised approach to the attribution of NP events, also to be used in future studies on NPSLE.

bmjopen-2016-015546supp001.pdf (96.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015546supp002.docx (16KB, docx)

bmjopen-2016-015546supp005.docx (32.3KB, docx)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AB, MG: substantial contributions to the conception of the work and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work related to accuracy and integrity; final approval of the version to be published;

AF, SA, LC and EM: substantial contributions to the acquisition of the data for the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work related to accuracy and integrity; final approval of the version to be published;

CS: substantial contributions to the analysis of the data for the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work related to accuracy and integrity; final approval of the version to be published;

GB, JH: substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data for the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work related to accuracy and integrity; final approval of the version to be published

Funding: SA has received grant from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico (CNPq304255/2015-7).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1. The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertsias GK, Boumpas DT. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of neuropsychiatric SLE manifestations. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010;6:358–67. 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Govoni M, Bortoluzzi A, Padovan M, et al. The diagnosis and clinical management of the neuropsychiatric manifestations of lupus. J Autoimmun 2016;74:41–72. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ainiala H, Loukkola J, Peltola J, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric syndromes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology 2001;57:496–500. 10.1212/WNL.57.3.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ainiala H, Hietaharju A, Loukkola J, et al. Validity of the new American College of Rheumatology criteria for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes: a population-based evaluation. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:419–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Monov S, Monova D. Classification criteria for neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: do they need a discussion? Hippokratia 2008;12:103–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanly JG. The neuropsychiatric SLE SLICC inception cohort study. Lupus 2008;17:1059–63. 10.1177/0961203308097568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Su L, et al. Prospective analysis of neuropsychiatric events in an international disease inception cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:529–35. 10.1136/ard.2008.106351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bortoluzzi A, Scirè CA, Bombardieri S, et al. Development and validation of a new algorithm for attribution of neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2015;54:891–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bossuyt PM, Cohen JF, Gatsonis CA, et al. STARD 2015: updated reporting guidelines for all diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:85 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.02.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725 10.1002/art.1780400928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fanouriakis A, Pamfil C, Rednic S, et al. Is it primary neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus? Performance of existing attribution models using physician judgment as the gold standard. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brey RL, Holliday SL, Saklad AR, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus: prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology 2002;58:1214–20. 10.1212/WNL.58.8.1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanna G, Bertolaccini ML, Cuadrado MJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence and association with antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol 2003;30:985–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mok CC, Lau CS, Wong RW. Neuropsychiatric manifestations and their clinical associations in southern Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2001;28:766–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petri M, Naqibuddin M, Carson KA, et al. Cognitive function in a systemic lupus erythematosus inception cohort. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1776–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hanly JG, Su L, Urowitz MB, et al. Mood Disorders in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Results From an International Inception Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1837–47. 10.1002/art.39111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, O’Keeffe AG, et al. Headache in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a prospective, international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2887–97. 10.1002/art.38106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lockshin MD. Editorial: Splitting Headache (Off). Arthritis & Rheumatism 2013;65:2759–61. 10.1002/art.38108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol 2002;29:288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanly JG. Attribution in the assessment of nervous system disease in SLE. Rheumatology 2015;54:755–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:195–205. 10.1136/ard.2007.070367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Su L, et al. Seizure disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus results from an international, prospective, inception cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1502–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Padovan M, Castellino G, Bortoluzzi A, et al. Factors and comorbidities associated with central nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective cross-sectional case-control study from a single center. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:129–35. 10.1007/s00296-010-1565-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LT. Epileptic seizures in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology 2004;63:1808–12. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000144178.32208.4F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mikdashi J, Krumholz A, Handwerger B. Factors at diagnosis predict subsequent occurrence of seizures in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology 2005;64:2102–7. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165959.98370.D5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015546supp004.pdf (176.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015546supp003.pdf (236.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015546supp001.pdf (96.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015546supp002.docx (16KB, docx)

bmjopen-2016-015546supp005.docx (32.3KB, docx)