Abstract

Introduction

Studies of the health effects of moist oral tobacco, snus, have produced inconsistent results. The main objective of this study is to examine the health effects of snus use on asthma, respiratory symptoms and sleep-related problems, a field that has not been investigated before.

Methods and material

This cross-sectional study was based on a postal questionnaire completed by 26 697 (59.3%) participants aged 16 to 75 years and living in Sweden. The questionnaire included questions on tobacco use, asthma, respiratory symptoms and sleeping problems. The association of snus use with asthma, respiratory symptoms and sleep-related symptoms was mainly tested in never-smokers (n=16 082).

Results

The current use of snus in never-smokers was associated with an increased risk of asthma (OR 1.51 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.77)), asthmatic symptoms, chronic bronchitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. This association was not present among ex-snus users. Snoring was independently related to both the former and current use of snus ((OR 1.37 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.68)) and (OR 1.59 (95% CI 1.34 to 1.89), respectively)). A higher risk of difficulty inducing sleep was seen among snus users.

Conclusion

Snus use was associated with a higher prevalence of asthma, respiratory symptoms and snoring. Healthcare professionals should be aware of these possible adverse effects of snus use.

Keywords: snus, tobacco, asthma, chronic bronchitis, snoring, sleep disturbances

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the first studies to investigate the association between the use of snus and respiratory and sleep-related symptoms.

The population is large which enables us to investigate subgroups such as never-smokers.

Data are self-reported and some subjects may therefore be misclassified.

The study is cross-sectional which makes it difficult to distinguish between causes and outcomes.

Introduction

Snus is a smokeless, moist tobacco product consisting mainly of tobacco, salt, water, humectants and flavouring.1 The tobacco in snus contains a number of harmful substances, including nicotine and tobacco-specific nitrosamines.2 In Sweden, where it is a very popular tobacco alternative, with 18% men and 4% women being current users, snus is regulated under food legislation.3 4 The highest proportion of snus users is found among men aged 40 years.5 In the mid-1990s, the prevalence of snus use among Swedish men surpassed the prevalence of smoking. The proportion of female snus users is rising, but it has still not reached the prevalence for women smokers.5 Compared with smoking, it has been suggested that the addiction to snus use is stronger, due to a lower cessation rate6 and reports of greater experience of nicotine dependence,7 however, other data suggest that snus cessation may be less difficult than cigarette cessation.8 Some authors have suggested that snus is as a good alternative for smoking cessation due to the beneficial health effects compared with cigarettes.9

Studies aiming to identify the risk of health effects as a result of snus use have not reported consistent results. A significant increase in pancreatic cancer has been observed,10 11 but reports regarding the association between snus use and oral and pharyngeal cancer are inconclusive.10–12 Snus use appears to increase the risk of short-term case fatality after suffering from acute myocardial infarction13 and stroke.14 An increased risk of heart failure among snus users has been reported, with a particularly high risk of non-ischaemic heart failure among elderly men.15

There is only sparse evidence regarding the potential effect of snus on respiratory health and sleep. An association between snus and asthma has been reported in one study16 and an elevated risk of insufficient sleep was found among smokeless tobacco users in another.17 The main objective of this paper was to investigate the health effects of snus use on asthma, respiratory symptoms and sleep-related problems in a large general population sample.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study is based on observations from a postal questionnaire sent to 45 000 randomly selected subjects as part of the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) survey in 2008.18 In Sweden, 26 697 (59.3%) participants responded. The subjects were aged 16 to 75 years and lived in four Swedish cities (Uppsala, Stockholm, Umeå and Gothenburg).16

Ethical approval was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden.

GA2LEN questionnaire

The questionnaire included questions on respiratory symptoms, asthma and smoking. The questions also covered gender, age, weight and height. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the values of weight and height. In Sweden, the questionnaire also included questions on the use of snus and sleep-related symptoms. Listed below are definitions relevant to this paper.

Snus users were defined as those giving a positive answer to both the questions ‘Have you ever used snus every day for at least 6 months?’ and ‘Do you currently use snus?’.

Smokers were defined as those giving a positive answer to the questions ‘Have you ever smoked at least one cigarette a day for at least 1 year?’ and ‘Have you smoked at all during the last month?’. Based on the answers to questions on snus use and smoking, the participants were divided into four groups: tobacco free, snus users, smokers and dual users.

Based on answers to the questions on snus use and smoking, the subjects were further divided into never-snus, ex-snus and current snus users, as well as into never-smokers, ex-smokers and current smokers.

Asthma was defined as a positive answer to either of the questions ‘Have you had an asthma attack during the last 12 months?’ or ‘Are you currently taking any asthma medication including inhalers, sprays or tablets?’. Childhood asthma was defined as reporting having had an attack of asthma before the age of 13 years.

Questions regarding asthmatic symptoms during the last 12 months included: (1) wheezing in the chest; (2) wheezing together with breathlessness; (3) wheezing without having a cold; (4) waking up with tightness in the chest; (5) waking up with shortness of breath and (6) waking up with a coughing attack.

Chronic bronchitis was defined as a positive answer to the question: ‘Are you used to having a cough almost every day with sputum production that lasts for at least 3 months every year during the winter?’.

Allergic rhinitis was defined as a positive answer to the question ‘Have you had hay fever or a runny nose because of other allergies during the last 12 months?’.

Chronic rhinosinusitis was defined as suggested by the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EP3OS) criteria 2007.19 It was considered to be present if participants stated that the following symptoms had been present for >12 weeks during the last 12 months: (1) nasal blockage, as well as one of the subsequent symptoms: (2) facial pain or pressure, (3) discoloured nasal discharge or (4) reduction or loss of smell. The disease was also considered to be present if both symptoms (2) and (3) were reported.

Sleep-related problems examined in this study were (1) snoring that is loud and interrupting, (2) difficulty inducing sleep (DIS), as in having a hard time falling asleep at night, (3) difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS), as in repeatedly waking up during the night, (4) being sleepy during the day (EDS) and (5) early morning awakening (EMA), as in waking up too early and having a hard time falling asleep again.20 Each group included subjects who claimed they had the problem at least three to five times a week. The use of hypnotics was defined as a positive answer to the question ‘Do you take medication for sleeping problems?’.

Educational level was divided into three categories. (1) College was defined as having attended college/university for >2½ years. (2) High school was defined as having attended high school or vocational school for >2 years. (3) Elementary school was defined as any education below the level of high school.

Activity level was divided into three categories depending on hours spent on intensive exercising per week. (1) Physically inactive was defined as zero hours a week. (2) Moderately physically active was defined as 0.5 to 3 hours a week. (3) Vigorously physically active was defined as 4 to 7 hours a week.

Data analysis

For statistical analyses, Stata V.12 was used. When comparing the characteristics of the study population, univariate analyses using the χ2 test were used. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to study independent associations between various symptoms and different groups of tobacco use after adjusting for potential confounders: gender, age, BMI, centre, educational level and physical activity. Subanalyses were performed in never-smokers and in never-smokers with reported asthma. Analyses of possible heterogeneity between the centres were performed using random effects meta-analysis. A p value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

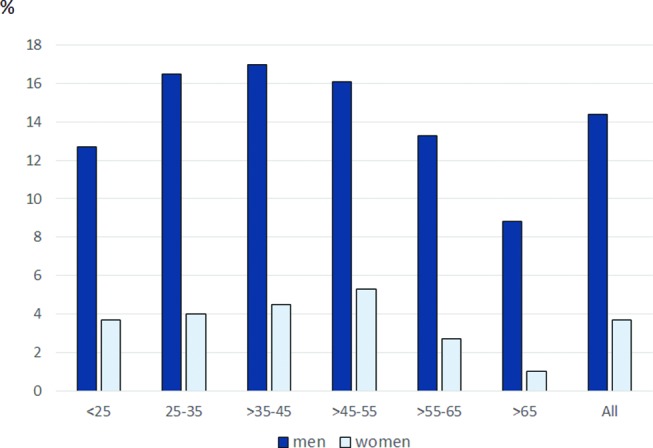

The frequency of snus use among men was highest in the 25–35 age group. The number of snus-using women was highest in the 45–55 age group, with a steep decrease thereafter. In overall terms, 18.0% of men and 4.7% of women in the study population used snus (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of men and women using snus among age groups.

In the whole population, snus use and dual use were highest in the 25–35 age group, whereas smoking was most prevalent at 55–65 years of age. The group of snus users had a higher BMI than the other groups. They were also more likely to be ex-smokers than persons in the tobacco-free group. Educational level and physical activity level were higher among snus users compared with smokers and dual users but lower compared with those who were tobacco free (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (%)

| Tobacco users | |||||

| Tobacco free (n=20 699) | Snus (n=2265) | Smokers (n=3136) | Smokers and snus (n=597) | p Value | |

| Women | 57.7 | 23.5 | 62.9 | 25.0 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| 16–25 | 15.4 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 15.2 | |

| 25–35 | 21.4 | 23.2 | 17.4 | 26.7 | |

| 35–45 | 17.6 | 21.5 | 16.7 | 16.8 | |

| 45–55 | 15.4 | 19.7 | 20.0 | 21.5 | |

| 55–65 | 17.7 | 16.5 | 23.2 | 14.9 | |

| >65 | 12.4 | 7.2 | 10.1 | 6.7 | |

| Body mass index | <0.001 | ||||

| <20 | 8.6 | 4.7 | 9.9 | 5.8 | |

| 20–25 | 51.9 | 46.6 | 48.9 | 48.1 | |

| 25–30 | 30.1 | 36.2 | 30.9 | 35.3 | |

| >30 | 9.5 | 12.4 | 10.3 | 10.9 | |

| Ex-smokers | 26.8 | 48.1 | —- |

—— |

<0.001 |

| Educational level | <0.001 | ||||

| Elementary school | 15.0 | 12.5 | 23.6 | 18.6 | |

| High school | 31.6 | 42.9 | 40.7 | 45.8 | |

| College | 53.5 | 44.7 | 35.7 | 35.6 | |

| Activity level | <0.001 | ||||

| Physically inactive | 18.1 | 19.3 | 32.8 | 27.8 | |

| Moderately physically active | 62.8 | 62.0 | 55.1 | 58.7 | |

| Vigorously physically active | 19.0 | 18.7 | 12.1 | 13.5 | |

Tobacco use and symptoms

In table 2, we examined the association between tobacco use and symptoms after adjusting for likely confounders. Having asthma was independently related to using snus but not to smoking or the dual use of snus and cigarettes. Although the strongest associations with respiratory symptoms were found among smokers and dual users, snus users were more likely to suffer from wheezing and night-time chest tightness, as well as chronic bronchitis, allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis, compared with the tobacco-free group. Snoring, DIS, EDS and the use of hypnotics were associated with all three groups of tobacco use. Snus users had a decreased risk of DMS (table 2). The corresponding unadjusted associations were fairly similar to the adjusted estimates (see online supplementary Table S1).

Table 2.

The independent association between tobacco use and respiratory health and sleep-related symptoms (adjusted OR (95% CI))

| Tobacco users | |||

| Snus users (n=2265) | Smokers (n=3136) | Smokers and snus users (n=597) | |

| Asthma | 1.51 (1.28 to 1.77) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.13) | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.33) |

| Asthmatic symptoms | |||

| Wheezing | 1.50 (1.33 to 1.69) | 2.89 (2.64 to 3.17) | 2.09 (1.71 to 2.55) |

| Wheezing and breathlessness | 1.42 (1.23 to 1.65) | 2.11 (1.89 to 2.37) | 1.46 (1.12 to 1.90) |

| Wheezing without having a cold | 1.50 (1.30 to 1.73) | 2.67 (2.40 to 2.98) | 2.17 (1.73 to 2.73) |

| Night-time chest tightness | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.40) | 1.57 (1.40 to 1.75) | 1.43 (1.12 to 1.82) |

| Night-time attacks of breathlessness | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.24) | 1.44 (1.24 to 1.67) | 1.58 (1.16 to 2.13) |

| Night-time coughing | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 1.79 (1.64 to 1.94) | 1.79 (1.49 to 2.15) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 1.19 (1.03 to 1.37) | 2.39 (2.16 to 2.65) | 1.85 (1.48 to 2.31) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.17 (1.05 to 1.30) | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.11) | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.13) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 1.28 (1.09 to 1.50) | 1.78 (1.57 to 2.02) | 1.78 (1.38 to 2.29) |

| Sleeping problems | |||

| Snoring | 1.41 (1.25 to 1.58) | 1.78 (1.60 to 1.97) | 2.16 (1.77 to 2.63) |

| DIS | 1.76 (1.56 to 1.99) | 1.98 (1.79 to 2.19) | 2.95 (2.43 to 3.58) |

| DMS | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83) | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.06) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.12) |

| EDS | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.31) | 1.29 (1.19 to 1.41) | 1.38 (1.16 to 1.65) |

| EMA | 0.87 (0.76 to 1.00) | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.27) | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.17) |

| Use of hypnotics | 1.33 (1.07 to 1.65) | 2.08 (1.81 to 2.39) | 2.77 (2.05 to 3.74) |

Associations with a p value of <0.05 are marked as bold.

Adjusted for gender, age, BMI, centre, educational level and physical activity.

BMI, body mass index; DIS, difficulty initiating sleep; DMS, difficulty maintaining sleep; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; EMA, early morning awakening at least three to five nights/week.

bmjopen-2016-015486supp001.pdf (91.3KB, pdf)

Snus use in never-smokers

In never-smokers, there was an association between snus use and asthma, all the asthmatic symptoms, chronic bronchitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Sleeping problems with an increased risk among snus users were snoring and DIS. Also, among never-smokers, snus users had a decreased risk of DMS (table 3). The associations with asthma and nocturnal breathlessness became statistically non-significant when excluding subjects who have had attacks of asthma before the age of 13 years (n=1466) (adjusted OR (95% CI) 1.24 (0.89 to 1.71) and 1.32 (0.97 to 1.77), respectively). All the other association above remained statistically significant.

Table 3.

Association between snus and respiratory health and sleep-related symptoms in never-smokers (%) and adjusted OR

| Never smoked | ||||

| Tobacco free (n=14 914) |

Snus users (n=1168) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Asthma | 6.9 | 10.1 | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.20 to 1.85) |

| Asthmatic symptoms | ||||

| Wheezing | 12.9 | 18.8 | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.32 to 1.84) |

| Wheezing and breathlessness | 8.2 | 10.9 | 0.002 | 1.38 (1.12 to 1.69) |

| Wheezing without having a cold | 8.0 | 11.8 | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.21 to 1.80) |

| Night-time chest tightness | 9.4 | 12.0 | 0.004 | 1.41 (1.16 to 1.71) |

| Night-time attacks of breathlessness | 4.8 | 6.1 | 0.045 | 1.39 (1.07 to 1.82) |

| Night-time coughing | 23.1 | 23.1 | 0.987 | 1.27 (1.09 to 1.47) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 9.0 | 12.5 | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.21 to 1.78) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 24.7 | 28.0 | 0.012 | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.31) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 7.1 | 9.3 | 0.005 | 1.37 (1.11 to 1.70) |

| Sleeping problems | ||||

| Snoring | 11.7 | 19.0 | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.29 to 1.82) |

| DIS | 11.1 | 16.5 | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.44 to 2.03) |

| DMS | 25.3 | 15.8 | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.59 to 0.84) |

| EDS | 28.7 | 29.8 | 0.433 | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) |

| EMA | 12.7 | 9.0 | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.04) |

| Use of hypnotics | 4.0 | 3.1 | 0.143 | 1.24 (0.85 to 1.80) |

Associations with a p value of <0.05 are marked as bold.

Adjusted for gender, age, BMI, centre, educational level and physical activity.

BMI, body mass index; DIS, difficulty inducing sleep; DMS, difficulty maintaining sleep; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; EMA, early morning awakening at least three to five nights/week.

No significant heterogeneity between the centres was found between snus use and the health outcomes except for bronchitis where the association was particularly strong in Stockholm (adjusted OR (95% CI) 2.35 (1.52 to 3.62)), whereas no significant association was found in Uppsala (OR 0.97 (0.60 to 1.57), pheterogeneity=0.04). The pooled estimates of the meta-analyses were very similar to those found in table 3 (data not shown). When snus users among asthma patients who had never smoked were examined, the only symptom with a significantly elevated risk was snoring (OR 2.68 (1.58 to 4.55)).

History of snus use in never-smokers

Current snus use was an independent risk factor for having asthma, asthmatic symptoms, chronic bronchitis and chronic rhinosinusitis, while being an ex-snus user was not (table 4). Snoring was independently related to both the former and the current use of snus. A higher risk of DIS was seen among current snus users. Current snus users had a decreased risk of DMS, whereas ex-snus use was an independent risk factor for the problem. Being an ex-snus user was also an independent risk factor for EMA (table 4).

Table 4.

Association between a history of snus use and respiratory health and sleep-related symptoms among never-smokers (adjusted OR (95% CI)

| Ex-snus users (n=832) | Snus users (n=1169) | |

| Asthma | 1.06 (0.79 to 1.40) | 1.50 (1.21 to 1.86) |

| Asthmatic symptoms | ||

| Wheezing | 1.10 (0.89 to 1.36) | 1.56 (1.32 to 1.84) |

| Wheezing and breathlessness | 1.00 (0.76 to 1.31) | 1.37 (1.12 to 1.69) |

| Wheezing without having a cold | 1.24 (0.97 to 1.59) | 1.51 (1.23 to 1.84) |

| Night-time chest tightness | 1.01 (0.78 to 1.30) | 1.41 (1.16 to 1.71) |

| Night-time attacks of breathlessness | 1.27 (0.92 to 1.76) | 1.42 (1.09 to 1.86) |

| Night-time coughing | 1.14 (0.96 to 1.37) | 1.29 (1.11 to 1.50) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.19) | 1.45 (1.20 to 1.76) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.95 (0.80 to 1.12) | 1.13 (0.98 to 1.30) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 0.95 (0.71 to 1.28) | 1.36 (1.10 to 1.70) |

| Sleeping problems | ||

| Snoring | 1.37 (1.12 to 1.68) | 1.59 (1.34 to 1.89) |

| DIS | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.05) | 1.68 (1.41 to 2.00) |

| DMS | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.42) | 0.72 (0.60 to 0.85) |

| EDS | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.18) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) |

| EMA | 1.28 (1.03 to 1.59) | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.06) |

| Use of hypnotics | 1.32 (0.87 to 2.01) | 1.26 (0.87 to 1.84) |

Adjusted for gender, age, BMI, centre, educational level and physical activity.

BMI, body mass index; DIS, difficulty initiating sleep; DMS, difficulty maintaining sleep; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; EMA, early morning awakening at least three to five nights/week.

Discussion

Our results reveal a previously unknown association between snus use and negative health effects on the respiratory tract. An increased risk of asthma, asthmatic and other respiratory symptoms was observed among snus users. An association between snus use and sleep-related problems was mixed with an increased risk of snoring and DIS but a decreased risk of DMS.

In the present study, 18% of men and 4.7% of women were using snus either exclusively or in combination with smoking. This is similar to the prevalence of snus use reported in a Swedish official statistics.4 According to our findings, snus use is proportionally higher in younger age groups and among men than women, indicating an earlier initiation.

When compared with the tobacco-free group, a significant risk of asthma was observed among snus users but not among smokers and dual users. There is a possibility of reverse causation. Smoking is known to cause negative effects on asthma,21 the switch from smoking to snus use among asthmatic patients could possibly explain some of the associations between snus use and asthma. However, the fact that snus users who had never smoked also had an elevated risk of asthma and asthmatic symptoms excludes this possibility. This difference between snus users and smokers also raised concerns about whether asthmatic patients could be more prone to initiating snus use than cigarette smoking. Because the association with asthma and asthmatic symptoms was only present among current snus users but not ex-users of snus, this seems an unlikely explanation. We also found an association between snus use and respiratory symptoms when excluding participants who had childhood asthma. These findings suggest that snus causes an alteration in the lower respiratory tract, resulting in an increased likelihood of suffering from asthma and asthmatic symptoms. As asthmatic patients are a growing challenge among health professionals today,22 these results deserve attention and further investigation. Similarly, to asthma and asthmatic symptoms, the risk of chronic bronchitis and chronic rhinosinusitis was only elevated among current snus users but not ex-snus users.

Current snus use was associated with snoring and, as the association remained present among ex-snus users, this suggests a partly irreversible effect from snus use on factors leading to snoring. Snoring is caused by high-frequency oscillation of the soft palate, pharyngeal wall, epiglottis and tongue during sleep, due to the limited flow of air through the upper airways.23 The causes of limited airflow among patients who snore are diverse.24 25 There are data indicating that, once snoring occurs, it causes progressive irreversible local neurogenic lesions, caused by the trauma of snoring.26 In former studies, hypnotics27 and alcohol consumption28 have been associated with snoring. Adjustment for the use of hypnotics did not have any impact on the risk (results not shown), excluding it as an interfering factor in this study. However, we were not able to adjust for alcohol consumption, as the GA2LEN questionnaire did not include any questions about alcohol. It could thus serve as a confounder in our results. Obesity, gender, age and cigarette smoking are also possible confounders,27 all of which were adjusted for in our analyses.

In the group of snus users who had never smoked, being an asthma patient elevated the risk of snoring from 1.53 to 2.68. This implies that being an asthmatic patient increases the sensitivity to possible effects of snus use contributing to snoring. Deterioration in health-related quality of life in asthmatic patients suffering from snoring has been reported.29 The possible prevention of snoring by reducing snus initiation among those suffering from asthma should therefore be prioritised.

The risk of DMS was found to be decreased among current snus users but increased among ex-snus users. Ex-snus users also ran an increased risk of EMA. These results suggest that snus use improves sleep and that a cessation leads to exacerbation. In spite of this, current snus users had an increased risk of DIS, but ex-snus users did not, which indicates mixed effects on the quality of sleep.

The biological explanation for the association between snus use and health outcomes in the present study is unknown. Gastro-oesophageal reflux is associated with smoking,30 respiratory symptoms and snoring,31 but the association between reflux and snus use is less clear.32 Snus use was in one study found to be associated with an increased transfer factor for nitric oxide and a decrease in alveolar nitric oxide concentration indicating that snus may have an effect also on the lower airways.33

The main strength of this study is the use of a large database from a random general population sample. The response rate was lowest in Gothenburg (54.9%) and highest in Uppsala (59.1%).20 This response rate is somewhat lower than that previous epidemiological studies of the Swedish population have achieved,34 35 which is a limitation. In addition, the fact that this is a cross-sectional study makes it difficult to distinguish between causes and outcomes. A longitudinal study would be beneficial in order to indicate whether causation is present between snus use and these symptoms or only a connection. The fact that participants reported their history of snus use was, however, a great advantage, which helped us to draw conclusions about associations. It would have been beneficial to include questions on the amount of snus used. We also lack data on alcohol consumption, which is a limitation as there are studies showing an association between use of snus and a higher use of alcohol.36 It is also possible that some of the associations between snus use and snoring are related to higher alcohol use in participants using snus.37 Another limitation is the fact that the answers to the questionnaire are self-reported which might lead to underestimation or overestimation in some categories, especially those demanding more than a yes or no answer.16 It is, however, unlikely that the degree of underestimation or overestimation would differ between groups of tobacco use. We did not adjust for passive smoking, but we know from previous studies that the prevalence of passive smoking is very low in Sweden (<10%)38 so we do not think that this has influenced our results.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this field of effects has not been examined before. Further investigations will be needed to draw conclusions on possible reasons for limited airflow in the upper airways, an inflamed/mucus-secreting respiratory tract and a mixed impact on the quality of sleep among snus users. Moreover, these results should be supported by further studies. Our results are important when considering tobacco control policies and can provide input to the discussion of whether snus is a good alternative for smoking cessation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AG and CJ: analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RM, LE, BF, KF, EL and CJ: supervised the study and contributed to the design of present data analyses. All coauthors: revised critically the manuscript.

Funding: The GA2LEN survey was supported financially by the EU Sixth Framework Programme for Research, contract no FOOD-CT-2004–5 06 378. The study was also supported financially by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, the Swedish Asthma and Allergy Foundation and the Swedish Association against Heart and Lung Diseases, the Centre for Allergy Research at the Karolinska Institutet, the Karolinska Institutet and AstraZeneca Translational Science Centre Collaboration Research Program, and the Science for Life Laboratory Stockholm and AstraZeneca Collaboration Research Program. The Gothenburg part of the study was mainly funded by the VBG Group Centre for Asthma and Allergy Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset is still subject to further analyses, but will continue to be held and managed by the Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. Relevant anonymised data are available on reasonable request from the authors.

References

- 1.Digard H, Errington G, Richter A, et al. Patterns and behaviors of snus consumption in Sweden. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:1175–81. 10.1093/ntr/ntp118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Smokeless tobacco and some tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 2007;89:1–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Digard H, Gale N, Errington G, et al. Multi-analyte approach for determining the extraction of tobacco constituents from pouched snus by consumers during use. Chem Cent J 2013;7:55 10.1186/1752-153X-7-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobaksvanor — Folkhälsomyndigheten 2016. [Available from: http://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/amnesomraden/statistik-och-undersokningar/enkater-och-undersokningar/nationella-folkhalsoenkaten/levnadsvanor/tobaksvanor/

- 5.Norberg M, Lundqvist G, Nilsson M, et al. Changing patterns of tobacco use in a middle-aged population – the role of snus, gender, age, and education. Glob Health Action 2011;4:5613 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundqvist G, Sandström H, Ohman A, et al. Patterns of tobacco use: a 10-year follow-up study of smoking and snus habits in a middle-aged swedish population. Scand J Public Health 2009;37:161–7. 10.1177/1403494808096169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Post A, Gilljam H, Rosendahl I, et al. Symptoms of nicotine dependence in a cohort of swedish youths: a comparison between smokers, smokeless tobacco users and dual tobacco users. Addiction 2010;105:740–6. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagerström K, Eissenberg T. Dependence on tobacco and nicotine products: a case for product-specific assessment. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:1382–90. 10.1093/ntr/nts007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartner CE, Hall WD, Vos T, et al. Assessment of swedish snus for tobacco harm reduction: an epidemiological modelling study. Lancet 2007;369:2010–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60677-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo J, Ye W, Zendehdel K, et al. Oral use of swedish moist snuff (snus) and risk for cancer of the mouth, lung, and pancreas in male construction workers: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2007;369:2015–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60678-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boffetta P, Aagnes B, Weiderpass E, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of cancer of the pancreas and other organs. Int J Cancer 2005;114:992–5. 10.1002/ijc.20811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roosaar A, Johansson AL, Sandborgh-Englund G, et al. Cancer and mortality among users and nonusers of snus. Int J Cancer 2008;123:168–73. 10.1002/ijc.23469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansson J, Galanti MR, Hergens MP, et al. Use of snus and acute myocardial infarction: pooled analysis of eight prospective observational studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:771–9. 10.1007/s10654-012-9704-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansson J, Galanti MR, Hergens MP, et al. Snus (Swedish smokeless tobacco) use and risk of stroke: pooled analyses of incidence and survival. J Intern Med 2014;276:87–95. 10.1111/joim.12219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arefalk G, Hergens MP, Ingelsson E, et al. Smokeless tobacco (snus) and risk of heart failure: results from two swedish cohorts. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;19:1120–7. 10.1177/1741826711420003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerning C, Martinander E, Bjerg A, et al. Asthma and physical activity--a population based study results from the swedish GA(2)LEN survey. Respir Med 2013;107:1651–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabanayagam C, Shankar A. The association between active smoking, smokeless tobacco, second-hand smoke exposure and insufficient sleep. Sleep Med 2011;12:7–11. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis D, Newson R, Lotvall J, et al. Asthma in adults and its association with chronic rhinosinusitis: the GA2LEN survey in Europe. Allergy 2012;67:91–8. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomassen P, Newson RB, Hoffmans R, et al. Reliability of EP3OS symptom criteria and nasal endoscopy in the assessment of chronic rhinosinusitis--a GA² LEN study. Allergy 2011;66:556–61. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundbom F, Lindberg E, Bjerg A, et al. Asthma symptoms and nasal congestion as independent risk factors for insomnia in a general population: results from the GA(2)LEN survey. Allergy 2013;68:213–9. 10.1111/all.12079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietinalho A, Pelkonen A, Rytilä P. Linkage between smoking and asthma. Allergy 2009;64:1722–7. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundbäck B, Backman H, Lötvall J, et al. Is asthma prevalence still increasing? Expert Rev Respir Med 2016;10:39–51. 10.1586/17476348.2016.1114417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liistro G, Stănescu DC, Veriter C, et al. Pattern of snoring in obstructive sleep apnea patients and in heavy snorers. Sleep 1991;14:517–25. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saha S, Taheri M, Mossuavi Z, et al. Effects of changing in the neck circumference during sleep on snoring sound characteristics. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2015;2015:2235–8. 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7318836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bury SB, Singh A. The role of nasal treatments in snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;23:1–46. 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friberg D, Ansved T, Borg K, et al. Histological indications of a progressive snorers disease in an upper airway muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:586–93. 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.96-06049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloom JW, Kaltenborn WT, Quan SF. Risk factors in a general population for snoring. importance of cigarette smoking and obesity. Chest 1988;93:678–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riemann R, Volk R, Müller A, et al. The influence of nocturnal alcohol ingestion on snoring. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010;267:1147–56. 10.1007/s00405-009-1163-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekici A, Ekici M, Kurtipek E, et al. Association of asthma-related symptoms with snoring and apnea and effect on health-related quality of life. Chest 2005;128:3358–63. 10.1378/chest.128.5.3358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohata Y, Fujiwara Y, Watanabe T, et al. Long-Term benefits of smoking cessation on gastroesophageal reflux disease and Health-Related quality of life. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147860 10.1371/journal.pone.0147860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emilsson ÖI, Bengtsson A, Franklin KA, et al. Nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux, asthma and symptoms of OSA: a longitudinal, general population study. Eur Respir J 2013;41:1347–54. 10.1183/09031936.00052512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lie TM, Bomme M, Hveem K, et al. Snus and risk of gastroesophageal reflux. A population-based case-control study: the HUNT study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017;52:193–8. 10.1080/00365521.2016.1245775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malinovschi A, Janson C, Holmkvist T, et al. Effect of smoking on exhaled nitric oxide and flow-independent nitric oxide exchange parameters. Eur Respir J 2006;28:339–45. 10.1183/09031936.06.00113705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janson C, De Backer W, Gislason T, et al. Increased prevalence of sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness in subjects with bronchial asthma: a population study of young adults in three european countries. Eur Respir J 1996;9:2132–8. 10.1183/09031936.96.09102132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundberg R, Torén K, Franklin KA, et al. Asthma in men and women: treatment adherence, anxiety, and quality of sleep. Respir Med 2010;104:337–44. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norberg M, Malmberg G, Ng N, et al. Use of moist smokeless tobacco (snus) and the risk of development of alcohol dependence: a cohort study in a middle-aged population in Sweden. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;149:151–7. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang R, Ho SY, Lo WS, Sy H, Ws L, et al. Alcohol consumption and sleep problems in Hong Kong adolescents. Sleep Med 2013;14:877–82. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janson C, Künzli N, de Marco R, et al. Changes in active and passive smoking in the european community respiratory health survey. Eur Respir J 2006;27:517–24. 10.1183/09031936.06.00106605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015486supp001.pdf (91.3KB, pdf)