Abstract

Aims

Heart failure (HF) patients with a mid-range LVEF (HFmrEF) are not well characterized. Accordingly, we examined the epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical outcomes of HF patients with an LV EF of 40–50%.

Methods and Results

We identified patients with an LVEF between 40–50% at enrollment into a HF registry, and determined whether LVEF was improved, worsened, or the same compared to a prior LVEF. Three subgroups of HFmrEF patients were identified: HFmrEF improved (prior LVEF < 40%); HFmrEF deteriorated (prior LVEF > 50%); HFmrEF unchanged (prior LVEF 40–50%). The majority of patients (73%) were HFmrEF improved, 17% were HFmrEF deteriorated and 10% were HFmrEF unhanged. The demographics of the HFmrEF cohort were heterogeneous, with more CAD in the HFmrEF improved group and a more hypertension and diastolic dysfunction in the HFmrEF deteriorated group. HFmrEF improved patients had significantly (p < 0.001) better clinical outcomes relative to matched patients with HFrEF, and significantly (P < 0.01) improved clinical outcomes relative to HFmrEF deteriorated patients, whereas clinical outcomes of the HFmrEF deteriorated subgroup of patients were not significantly different from matched HFpEF patients.

Conclusions

Patients with a mid-range EF are heterogeneous. Obtaining historical information with regard to prior LVEF allows one to identify a distinct pathophysiological substrate and clinical course for HFmrEF patients. Viewed together, these results suggest that in the modern era of HF therapeutics, the use of LVEF to categorize the pathophysiology of HF may be misleading, and argue for establishing a new taxonomy for classifying HF patients.

INTRODUCTION

The clinical syndrome of heart failure (HF) is associated with a wide spectrum of abnormalities of left ventricular (LV) structure and function, ranging from a normal LV chamber size with a preserved ejection fraction (EF), to severe LV chamber dilatation with a markedly reduced EF. LV EF is considered important with respect to classifying HF patients because of differing patient demographics, prognosis, as well as the response to HF therapies.1 Current American HF guidelines divide the HF population into two separate groups of patients based on their LV EF: those with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, EF<40%) and those with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, EF>50%).2 However, it has also become clear that the clinical syndrome of HF may develop in patients with LV EFs that range between 40–50%.3 Although it was originally suggested that the patients with a mid-range LV EF between 40–50% represented HFpEF patients with isolated diastolic dysfunction whose LV EF declined secondary to the development of systolic dysfunction,4, 5 the recognition that LV EF improves in HFrEF patients who are treated with evidence based medical and device therapies6 suggests that the patients with a mid-range LV EF are likely to be heterogeneous and may not have a single pathophysiological substrate. The 2016 European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Guidelines recognize this as a distinct group of heart failure and illustrates the need to better understand their underlying characteristics, pathophysiology, and treatment.

Given that the prevalence of patients with a mid-range LV EF (40–50%) is increasing in contemporary heart failure clinics, and given that there are no current management guidelines for this group of patients, we sought to determine the epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical outcomes of patients with a mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) by performing a case control study of patients who were enrolled in the Washington University Heart Failure Registry.7 Here we show that the epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical outcomes of a contemporary group of patients with an LV EF between 40–50% are remarkably heterogeneous with respect to pathophysiology and clinical outcomes.

METHODS

Patient Demographics

We identified patients with a documented LV EF between 40–50% at the time of enrollment in the Washington University Heart Failure Registry. The Washington University Heart Failure Registry was designed as a prospective registry of inpatients and outpatients with clinical evidence of HF irrespective of LV EF. All patients were enrolled in the registry from March 2010 – August 2013 without any selection bias. Detailed patient information was prospectively collected and patient vital status followed for two years after enrollment, as previously described.7 For the purpose of the present analysis, the patients with an LV EF from 40–50% are referred to as HF with a mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF). In order to determine whether the LV EF at the time of enrollment was improved, worsened, or the same as a prior assessments of LV EF, we performed a retrospective chart review of the HFmrEF patients. The prior ejection fractions were selected from the first documented echocardiogram for the diagnosis of heart failure. The HFmrEF patients whose prior ejection was < 40% prior to enrollment in the registry are referred to as “HFmrEF improved” and the HFmrEF patients whose EF was > 50% prior to enrollment are referred to as “HFmrEF deteriorated.” The HFmrEF patients whose ejection fraction was between 40–50% prior to enrollment and are referred to as “HFmrEF unchanged.”

Patients without a known prior EF were excluded from the analysis (n=4). When available, prior outpatient echocardiographic assessment of LV function was preferentially used, rather than echocardiographic data acquired as an inpatient, in order to avoid any potential bias related to transient depression in LV function (e.g. during an acute episode of acute decompensated heart failure). Approval was obtained from the Washington University Institutional Review Board and the study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written, informed consent prior to participation.

Clinical Outcomes

The clinical outcomes that were assessed included death, cardiac transplantation, HF hospitalization, cardiac hospitalization, death/transplant/HF hospitalization, death/transplant/cardiac hospitalization, and death/transplant/any hospitalization. Clinical outcomes after enrollment were collected by telephone interviews at home or in-person interviews at clinic visits. These were supplemented with reviews of the medical record at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. HF hospitalization was defined as an admission for acute decompensated heart failure in the discharge summary. Cardiac hospitalization included heart failure exacerbations, in addition to other cardiac related diagnosis such as acute coronary syndrome and arrhythmias. For patients who were unreachable by telephone and did not have any documentation of contact in their medical record, vital status was determined by the social security death index.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between HFmrEF improved, HFmrEF unchanged, and HFmrEF deteriorated were conducted using ANOVA and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical data, respectively. For ordinal and non-normal variables, the data were summarized by the median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile) and compared via the Kruskal-Wallis test. Clinical outcomes were evaluated through time-to-event analyses. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were created by for each group and compared using the log-rank test. The start time was the date of entry into the HF registry. Patients were followed until first event occurrence or last follow-up. After an overall significant finding, pairwise comparisons of the KM curves were made with an adjustment for multiple testing based on the Tukey-Kramer method.

In order to evaluate clinical outcomes, HFmrEF improved and HFmrEF deteriorated patients were age (± 5 years) and gender matched to HFrEF (EF < 40%) and HFpEF (EF > 50%) patients contemporaneously enrolled in the registry. A Cox proportional hazards model was built to determine the risk of each outcome for each group. A shared frailty model approach was used to account for the matching. The matched datasets were combined so that the association between HF groups and outcome could be compared between matched samples, HFrEF matched sample vs. HFpEF matched sample. A Cox model that included indicator variables for each HFmrEF group and matched samples (HFrEF/HFpEF) as well as the interaction between the two was created. For each outcome variable, the hazard ratio of HFmrEF patients was determined within each matched sample, and then compared via the interaction for each outcome. All data analysis was conducted in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

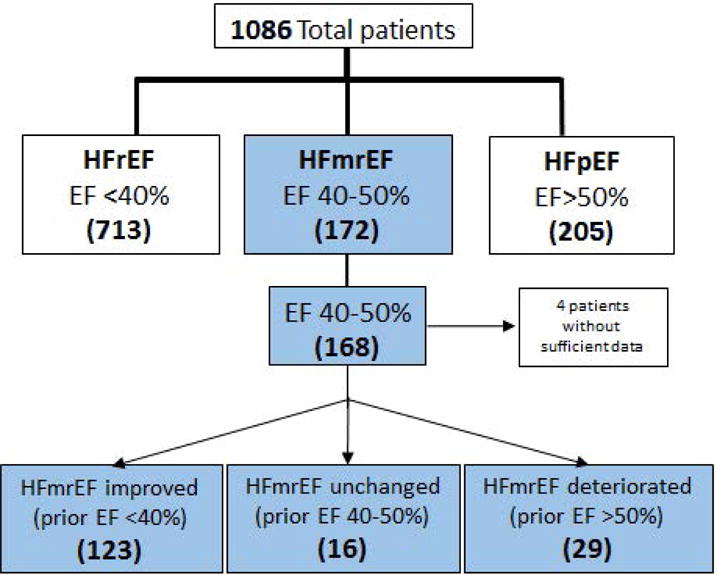

Of the 1091 patients enrolled in the Wash U heart failure registry, 172 had an LV EF between 40% and 50% at the time of enrollment (Figure 1). Review of the electronic medical records (EMR) revealed that four of the HFmrEF patients did not have known prior LV EF, and were therefore excluded from further analysis. Of the remaining 168 HFmrEF patients 123 (73%) had a previous LV EF < 40% (prior EF 2.9 ± 2.4 years prior to enrollment), 29 (17%) had a previous LV EF >50% (prior EF 3.3 ± 2.6 years prior to enrollment), and 16 (10%) had a previous LV EF between 40–50% (prior EF 3.8 ± 3.2 years prior to enrollment).

Figure 1.

Patient Selection. Consort diagram of the patients enrolled in the Washington University Heart Failure Registry. Patients with an LV ejection fraction from 40–50% (HFmrEF) subdivided into 3 different subgroups (see text for details). The numbers of patients are given in parenthesis.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of HFmrEF patients

The demographics of the entire cohort of HFmrEF patients at the time of entry into the registry, as well as the 3 subgroups of HFmrEF patients are outlined in Table 1. As shown, the age for the entire cohort of HFmrEF patients was 55.6 ± 13.1 years, with 54% male patients, 76% Caucasian and 24% African Americans. The major co-morbidities for the HFmrEF group included hypertension (51%), hyperlipidemia (35%), diabetes (26%), coronary artery disease (25%), obstructive sleep apnea (21%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (9%). The distribution of NYHA functional class for the HFmrEF cohort was: 18% class I, 61% class II, 18% class IIIand 4% class IV. The baseline demographics for the HFmrEF improved, HFmrEF unchanged, and the HFmrEF deteriorated were relatively well matched, with the exception that there was a significantly greater prevalence of a history hypertension in the HFmrEF deteriorated group (p=0.043). However, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures were not different among the HFmrEF subgroups at the time of enrollment.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Variable | Overall (N=168) |

HFmrEF improved (N=123) |

HFmrEF unchanged (N=16) |

HFmrEF deteriorated (N=29) |

P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 56 | ± 13.09 | 55 | ± 13.46 | 57 | ± 15.76 | 56 | ± 9.87 | 0.86 |

| Caucasian | 127 | (76%) | 90 | (73%) | 13 | (81%) | 24 | (83%) | 0.55 |

| African American | 41 | (24%) | 33 | (27%) | 3 | (19%) | 5 | (17%) | 0.55 |

| Male | 91 | (54%) | 70 | (57%) | 6 | (38%) | 15 | (52%) | 0.35 |

| Diabetes | 44 | (26%) | 31 | (25%) | 3 | (19%) | 10 | (34%) | 0.50 |

| Hypertension | 85 | (51%) | 60 | (49%) | 5 | (31%) | 20 | (69%) | 0.043 |

| CAD | 42 | (25%) | 32 | (26%) | 5 | (31%) | 5 | (17%) | 0.58 |

| COPD | 15 | (9%) | 13 | (11%) | 2 | (13%) | 0 | (0%) | 0.13 |

| PVD | 6 | (4%) | 4 | (3%) | 1 | (6%) | 1 | (3%) | 0.63 |

| CVA/TIA | 13 | (8%) | 7 | (6%) | 1 | (6%) | 5 | (17%) | 0.11 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 59 | (35%) | 40 | (33%) | 6 | (38%) | 13 | (45%) | 0.47 |

| OSA | 36 | (21%) | 26 | (21%) | 3 | (19%) | 7 | (24%) | 0.95 |

| Afib/Aflutter | 44 | (26%) | 28 | (23%) | 5 | (31%) | 11 | (38%) | 0.20 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 74 | ± 12.88 | 74 | ± 12.73 | 71 | ± 14.63 | 74 | ± 12.80 | 0.72 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 119 | ± 18.65 | 119 | ± 18.46 | 121 | ± 19.95 | 121 | ± 19.25 | 0.83 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 73 | ± 10.12 | 74 | ± 9.94 | 72 | ± 10.47 | 73 | ± 10.88 | 0.65 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure | 89 | ± 12.08 | 89 | ± 12.09 | 88 | ± 12.33 | 89 | ± 12.31 | 0.98 |

| Creatinine, Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.0 | (0.9,1.3) | 1.0 | (0.9,1.3) | 1.1 | (0.9,1.5) | 1.2 | (0.8,1.5) | 0.47 |

| Sodium | 140 | ± 2.97 | 140 | ± 2.88 | 140 | ± 1.50 | 139 | ± 3.88 | 0.69 |

| Glomerular Filtration Rate | 76 | ± 29.46 | 78 | ± 28.96 | 67 | ± 27.48 | 71 | ± 32.12 | 0.25 |

| Heart Failure Stage | 0.45 | ||||||||

| Stage B | 3 | (2%) | 2 | (2%) | 1 | (11%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Stage C | 126 | (96%) | 97 | (96%) | 8 | (89%) | 21 | (100%) | |

| Stage D | 2 | (2%) | 2 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| NYHA Class | 0.20 | ||||||||

| I | 30 | (18%) | 23 | (19%) | 4 | (25%) | 3 | (10%) | |

| II | 102 | (61%) | 78 | (63%) | 6 | (38%) | 18 | (62%) | |

| III | 30 | (18%) | 19 | (15%) | 5 | (31%) | 6 | (21%) | |

| IV | 6 | (4%) | 3 | (2%) | 1 | (6%) | 2 | (7%) | |

(Key: CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; PVD, Peripheral Vascular Disease; CVA/TIA, Cerebrovascular Accident/Transient Ischemic Attack’ OSA, Obstructive Sleep Apnea)

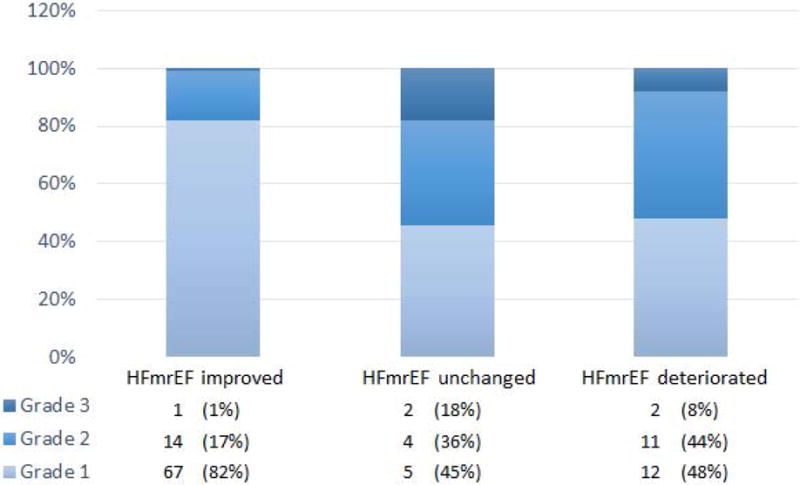

The etiology of HF for the entire cohort of HFmrEF patients, as well as the 3 subgroups of HFmrEF patients are summarized in Table 2. As shown, the vast majority of the patients in the HFmrEF group were comprised of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (65%), followed by patients ischemic heart disease (20%). Table 3 summarizes the echocardiographic data for the HFmrEF group of patients, as well as the 3 subgroups of HFmrEF patients. The mean EF at enrollment for the entire HFmrEF group was 45 ± 3.6%. There was no difference in mean LV EF in the 3 different subgroups of patients. Of note, the prior LV EF for the HFmrEF improved group was 25 ± 7.7%, which represented a ~ 20% improvement in the LV EF. The prior EF for the HFmrEF deteriorated group was 57 ± 4.9 % which represented ~ 12 % decline in LV EF. The mean LV end-diastolic dimension (LV EDD) for the HFmrEF cohort was 5.4 ± 0.7 cm, whereas the mean LV end-systolic dimension (LV ESD) for the 4.1 ± 0.8 cm. There were no differences in the LV EDD among the 3 different subgroups of HFmrEF patients; however, the LV ESD in the HFmrEF patients with a deteriorated EF was significantly less (p=0.022) than for HFmrEF recovered. The prevalence of diastolic dysfunction by Doppler echocardiography was 76% for the entire HFmrEF cohort. Interestingly, when we examined the degree of diastolic dysfunction in the HFmrEF improved group vs. the HFmrEF deteriorated group, there was a significantly greater degree of diastolic dysfunction in the HFmrEF deteriorated group when compared to the HFmrEF improved group, implying that the underlying pathophysiology of the HFmrEF group is heterogeneous (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Etiology of Heart Failure

| Variable | Overall (N=168) |

HFmrEF improved (N=123) |

HFmrEF unchanged (N=16) |

HFmrEF deteriorated (N=29) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic | 109 | (65%) | 86 | (70%) | 6 | (38%) | 17 | (59%) |

| Ischemic | 33 | (20%) | 24 | (20%) | 4 | (25%) | 5 | (17%) |

| Peripartum | 6 | (4%) | 4 | (3%) | 1 | (6%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Chemotherapy | 3 | (2%) | 3 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Hypertrophic | 3 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 3 | (10%) |

| Familial | 2 | (2%) | 2 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Valvular | 2 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 2 | (7%) |

| Amyloid | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Congenital Heart Disease | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (6%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Becker | 1 | (1%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Mixed | 1 | (1%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Myocarditis | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (6%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Noncompaction | 1 | (1%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Valvular Cardiomyopathy | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (6%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Other | 3 | (2%) | 1 | (1%) | 2 | (13%) | 0 | (0%) |

Table 3.

2-D Echocardiographic and Doppler Data

| Variable | Overall (N=168) |

HFmrEF improved (N=123) |

HFmrEF unchanged (N=16) |

HFmrEF deteriorated (N=29) |

P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment EF (%) | 45 | ± 3.6 | 45 | ± 3.5 | 47 | ± 3.5 | 46 | ± 3.6 | 0.06 |

| Prior EF (%) | 32 | ± 14.4 | 25 | ± 7.7 | 44 | ± 3.3 | 57 | ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Timing of LVEF prior to enrollment (years) | 3.1 | ± 2.5 | 2.9 | ± 2.4 | 3.8 | ± 3.2 | 3.3 | ± 2.6 | 0.347 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 5.4 | ± 0.74 | 5.5 | ± 0.72 | 5.4 | ± 0.48 | 5.2 | ± 0.94 | 0.30 |

| LVESD (cm) | 4.1 | ± 0.76 | 4.3 | ± 0.73 | 3.8 | ± 0.53 | 3.9 | ± 0.87 | 0.022 |

| Diastolic Dysfunction | 118 | (72%) | 82 | (68%) | 11 | (79%) | 25 | (86%) | 0.13 |

Key: (LVEDD, Left Ventricular End Diastolic Dimension; LVESD, Left Ventricular End Systolic Dimension)

Figure 2.

Degree of Diastolic Dysfunction for HFmrEF patients based on origin ejection fraction. Among patients with diastolic dysfunction, the percentage of HFmrEF improved, HFmrEF unchanged, and HFmrEF deteriorated patients with Grade I, II, and III diastolic dysfunction 18 is illustrated. Overall, there was a statistically significant increase in the degree of diastolic dysfunction in patients with more preserved ejection fractions at origin compared to those with reduced ejection fraction at origin (p<0.001 based on Fisher’s Exact Test).

Table 4 summarizes the medications for the entire HFmrEF patient cohort, as well as the 3 HFmrEF subgroups. Overall the use of evidence based medical therapies was very high for the entire cohort, with 88% of the patients on beta-blockers, 86% of the patients on ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and 42% of the patients on an aldosterone receptor blocker. The majority of the patients were on loop diuretics (69%). There was no difference in the medication use between the three HFmrEF groups; however, there was a trend towards greater digoxin use in HFmrEF improved patients and a trend towards more calcium channel blocker use in HFmrEF deteriorated patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Medications

| Variable | Overall (N=103) |

HFmrEF improved (N=78) |

HFmrEF unchanged (N=7) |

HFmrEF deteriorated (N=18) |

P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Blocker | 91 | (88%) | 68 | (87%) | 7 | (100%) | 16 | (89%) | 0.87 |

| ACE-I/ARB | 88 | (86%) | 67 | (87%) | 6 | (86%) | 15 | (83%) | 0.88 |

| Aldosterone Receptor Blocker | 43 | (42%) | 34 | (44%) | 3 | (43%) | 6 | (33%) | 0.78 |

| Hydralazine | 8 | (8%) | 7 | (9%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (6%) | 1.00 |

| Isosorbide | 5 | (5%) | 3 | (4%) | 1 | (14%) | 1 | (6%) | 0.22 |

| Loop Diuretic | 71 | (69%) | 52 | (67%) | 5 | (71%) | 14 | (78%) | 0.70 |

| Statin | 43 | (42%) | 33 | (42%) | 3 | (43%) | 7 | (39%) | 1.00 |

| Aspirin | 58 | (56%) | 45 | (58%) | 5 | (71%) | 8 | (44%) | 0.46 |

| Thypyrinidiene | 10 | (10%) | 6 | (8%) | 2 | (29%) | 2 | (11%) | 0.16 |

| Digoxin | 31 | (30%) | 24 | (31%) | 4 | (57%) | 3 | (17%) | 0.16 |

| Thiazide | 5 | (5%) | 4 | (5%) | 1 | (14%) | 0 | (0%) | 0.33 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 3 | (3%) | 1 | (1%) | 1 | (14%) | 1 | (6%) | 0.08 |

| Anticoagulant | 22 | (21%) | 14 | (18%) | 1 | (14%) | 7 | (39%) | 0.12 |

| Antiarrhythmic | 12 | (12%) | 8 | (10%) | 1 | (14%) | 3 | (17%) | 0.45 |

Clinical Outcomes

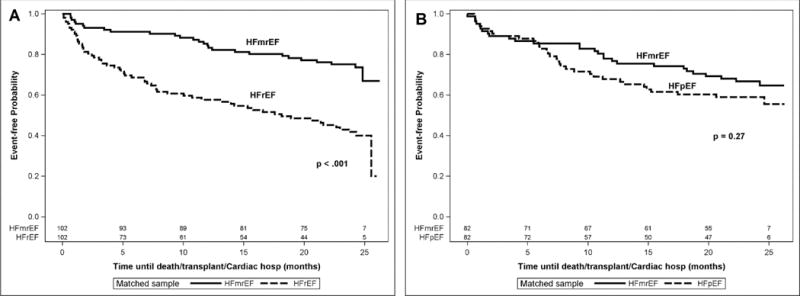

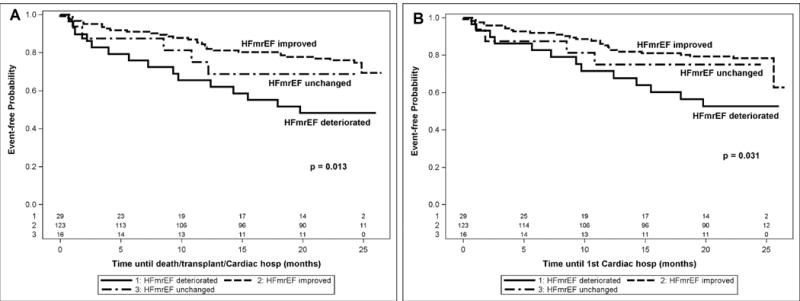

Figure 3 summarizes the clinical outcomes of the entire HFmrEF cohort compared to age and gender matched HFrEF patients (n=102) and age and gender matched with HFpEF patients (n=82). The salient finding shown in Figure 3A, is that the composite of time to death, cardiac transplantation and cardiac hospitalization was significantly better (p < 0.001) for the HFmrEF patients when compared to the HFrEF patients, consistent with prior reports.8–10 In contrast, Figure 3B shows that the composite of time to death, cardiac transplantation and cardiac hospitalization was not significantly different (p = 0.27) in the HFmrEF patients when compared to HFpEF patients. We next compared the clinical outcomes for the 3 different subgroups of HFmrEF patients. Figure 4A shows that the HFmrEF improved subgroup had significantly (p = 0.011) improved freedom from death/transplant/cardiac hospitalization in comparison to the HFmrEF deteriorated population. This difference was led by time to first cardiac hospitalization (p = 0.029) as illustrated in Figure 4B. Further, there was no significant difference (p = 0.40) between groups for the time to first heart failure hospitalization (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Clinical Outcomes for HFmrEF, HFrEF, and HFpEF patients. Kaplan-Meier curves of the time to death/transplant/cardiac hospitalization for HFmrEF, HFrEF, HFpEF patients enrolled in the Washington University HF registry. A, Risk of death/transplant/cardiac hospitalization in HFmrEF patients (n= 102) compared with age and gender matched HFrEF patients (n=102). B, Risk of death/transplant/cardiac hospitalization in HFmrEF patients (n= 82) compared with age and gender matched HFpEF patients (n=82).

Figure 4.

Outcomes for HFmrEF patients based on prior LV ejection fraction. A, Kaplan-Meier curves of the time to death/transplant/cardiac hospitalization for HFmrEF improved, HFmrEF unchanged, and HFmrEF deteriorated patients with significant difference for HFmrEF improved compared to HFmrEF deteriorated only (p = 0.011 based on log-rank test of pairwise comparisons with multiple testing adjustment). B, Kaplan-Meier curves of the time to first cardiac hospitalization for HFmrEF improved, HFmrEF unchanged, and HFmrEF deteriorated patients with significant difference for HFmrEF improved compared to HFmrEF deteriorated only (p = 0.029 based on log-rank test of pairwise comparisons with multiple testing adjustment).

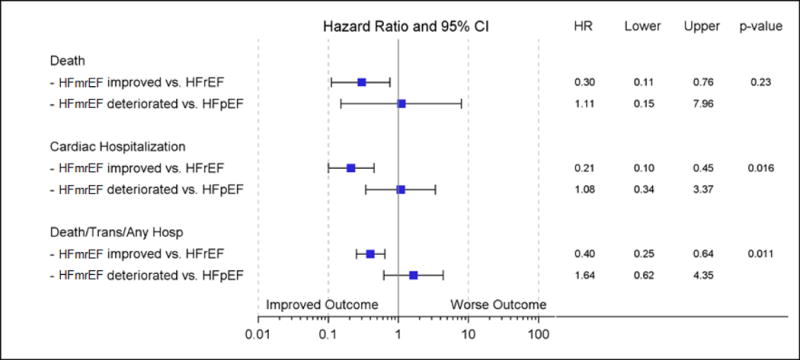

Figure 5 shows a Forest plot that compares multiple clinical outcomes for the HFmrEF improved patients compared to age and gender matched HFrEF patients (n=71) and HFmrEF deteriorated patients compared to age and gender matched patients with HFpEF (n=16). This analysis shows that there was a significant (p = 0.01) 70% improved freedom from death in HFmrEF improved patients when compared to HFrEF patients, whereas there was a non-significant (p=0.95) 11% increase in mortality risk for the HFmrEF deteriorated patients when compared with HFpEF patients. Similarly, both risk of cardiac hospitalization and the composite of death, cardiac transplantation and all cause hospitalization were significantly improved in the HFmrEF improved group (79% [p<0.001] and 60% [p<0.001], respectively) when compared with HFrEF patients, whereas risk of cardiac hospitalization and the composite of death, cardiac transplantation and all cause hospitalization were not significantly different in the (8% [p=0.90] and 64% [p=0.32] increased risk, respectively) HFmrEF deteriorated patients were compared to HFpEF patients. Additionally, the risk of cardiac hospitalization in HFmrEF improved vs. HFrEF was found to be different than that found in HFmrEF deteriorated vs. HFpEF (HR = 0.21 in HFmrEF improved vs. HFrEF compared to HR = 1.08 in HFmrEF deteriorated vs. HFpEF, p =0.016). Similarly, the risk of the composite death/transplant/any hospitalization in HFmrEF improved vs. HFrEF was found to be different than that found in HFmrEF deteriorated vs. HFpEF (HR = 0.40 in HFmrEF improved vs. HFrEF compared to HR = 1.64 in HFmrEF deteriorated vs. HFpEF, p =0.011). There was no significant difference between the comparison groups for all cause death.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of clinical outcomes for HFmrEF patients compared to patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF. The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals comparing clinical outcomes of death, time to first cardiac hospitalization and the composite of time to death/cardiac transplantation/all cause hospitalization for: HFmrEF improved patients (n=71) compared to age and gender matched HFrEF patients (n=71); and HFmrEF deteriorated (n=16) patients compared to age and gender matched HFpEF patients (n=16). All p-values represent the significance of the hazard ratios for HFmrEF improved patients compared with matched HFrEF patients or for HFmrEF deteriorated patients compared with matched HFpEF patients.

DISCUSSION

Although HF patients with a mid-range LV EF (HFmrEF) are encountered with increasing frequency in clinical practice, they represent a conundrum with respect to clinical management, insofar as they have not been studied in clinical trials.3 The ESC HF Guidelines, however, do recognize this as a distinct group of patients defined by their mid-range ejection fraction and having positive natriuretic peptide levels with relevant structural heart disease or diastolic dysfunction. The results of this study, in which we examined the epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical outcomes of a contemporary group of HF patients with an LV EF of 40–50%, suggest that the HFmrEF patients are a heterogeneous group of patients comprised of at least 3 different subsets. As shown in Figure 1, HFmrEF patients represented ~ 16% of all patients enrolled in the Washington University Heart Failure registry. We further sub-classified the HFmrEF patients into three different subgroups based on their prior LV EF, namely patients with a previous LV EF < 40% (HFmrEF improved), patients with a prior LV EF > 50% (HFmrEF deteriorated), and patients with a previous LV EF between 40–50% (HFmrEF unchanged). Consistent with a prior report,2 the majority of the patients in this study were classified as HFmrEF improved (73%), whereas 17% of the patients were classified as HFmrEF deteriorated, and only 10% were categorized as HFmrEF unhanged (Figure 1). Table 1 shows that the demographics of the HFmrEF population reflected whether the patient’s LV EF improved or deteriorated when compared to their prior assessment of LV function. The demographics of the HFmrEF improved subgroup revealed a greater prevalence of male patients and a greater prevalence of patients with CAD, consistent with the known demographics of HFrEF patients. In contrast, the HFmrEF deteriorated subgroup was comprised of more females with HTN and atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, consistent with the known demographics of patients with HFpEF. Another, important observation in the present study is that the HFmrEF deteriorated patients had significantly more advanced diastolic dysfunction by Doppler echocardiography when compared to the HFmrEF improved subgroup of patients (Figure 2), which may reflect the greater prevalence of a history of hypertension in the HFmrEF deteriorated patients.

A second important observation of this study is that the clinical outcomes of patients with HFmrEF were directly related to whether the prior ejection fraction was depressed (< 40%) or preserved (> 50%). That is, the cohort of HFmrEF improved patients had significantly better clinical outcomes relative to age and gender matched patients with HFrEF (Figure 5), as well as improved clinical outcomes relative to HFmrEF deteriorated patients (Figure 4). In contrast, the clinical outcomes of the HFmrEF deteriorated subgroup of patients was not significantly different from age and gender matched HFpEF patients (Figure 5). Importantly, the HFmrEF improved and HFmrEF deteriorated patients were receiving similar evidence based medical therapies, suggesting that the differences in clinical outcomes in the subgroups were not necessarily the result of the use of more evidence based medical therapies in the HFmrEF improved patients. Viewed together, the results of this study suggest that in contemporaneous population of HF patients, patients with a mid-range LV between 40–50 % are remarkably heterogeneous with respect to demographics, pathophysiology, and heart failure clinical events.

Heart Failure with a Mid-range Ejection Fraction

The current management of patients with heart failure is guided by categorizing patients based on their ejection fraction at the time of presentation: namely, HFrEF, defined in the literatures as an EF ≤ 35% or ≤ 40, or HFpEF, defined in the literature as an EFs ≥ 40%, 45%, 50%, 55%.1 More recently a third group of heart failure patients with LV EFs that range from 40–50% has been recognized as an unique “intermediate group,” whose pathophysiology is unclear.1 Although the nomenclature for this intermediate group has not been formalized, the term heart failure with a mid-range, borderline or between ejection fraction has been used previously,8–11 and herein the acronym HFmrEF has been employed in order to remain consistent with the current nomenclature of HFrEF and HFpEF. Surprisingly, very little is known with regard to the population HFmrEF patients. The extant literature suggests that the HFmrEF population is comprised of patients whose demographics lie somewhere in between those of HFpEF and HFrEF patients, but in aggregate are more similar to those of HFpEF patients, and are comprised of more female patients with a history of hypertension and a history of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter.8, 9, 12 However, HFmrEF patients have an increased burden of CAD burden when compared to HFpEF patients. Furthermore, the literature suggests that HFmrEF patients receive similar medications to those used by HFrEF and HFpEF patients, with HFrEF patients using more digoxin, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and HFpEF patients using more calcium channel blockers than HFmrEF patients. Beta-blocker use is similar in all of the groups that were studied.8, 9, 12 Of note, prior studies suggest that the clinical outcomes for HFmrEF patients are distinct from those of HFrEF and HFpEF. A 5 year follow-up of HFmrEF patients showed that all-cause mortality was increased when compared to patients HFpEF, but was significantly less than patients with HFrEF,10, 13 whereas HFmrEF mortality at 1 year post hospital discharge was similar to that of HFpEF.8, 9, 12 All cause re-hospitalization and heart failure re-hospitalization were less in HFmrEF and HFpEF patients when compared to HFrEF.8, 13 In the present study, we observed similar trends in clinical outcomes in the HFmrEF patients when compared to age and gender matched HFpEF and HFrEF patients (Figure 3 and supplemental tables 1 and 2).

The present study both confirms and extends the extant literature with respect to HFmrEF in several important respects. First, the results of this study show that > 90% of the HFmrEF patients either had a prior LV EF < 40% that improved on evidence based medical therapy, or had prior LV EF > 50% that deteriorated for unknown reasons. Thus, the overwhelming majority of patients categorized as “HFmrEF” do not represent a distinct and/or unique group of HF patients, but rather represent a heterogeneous group of HFrEF and HFpEF patients, in whom a change in LV EF resulted in their being categorized as being a unique intermediate subset of HF patients. Viewed within this context, the striking improved clinical outcomes in the HFmrEF patients when compared to age and gender matched HFpEF patients in this (Figure 3A) and prior studies, 10, 13 likely represents the well-recognized difference in clinical outcome between responders (i.e. patients whose LV EF improved) and non-responders to medical therapy. In this regard, it is equally interesting to note that patients with HFmrEF continue to have significant number of heart failure events, including death, and that the magnitude of these events was not significantly different from patients with HFpEF patients. The observation that HFmrEF patients with an improved LV EF continue to have recurrent HF events is consistent with prior reports which have shown that recovery of LV function is not necessarily associated with freedom from future heart failure events.14–16 A second unique observation in the present study was that the HFmrEF deteriorated patients had significantly more advanced diastolic dysfunction that the HFmrEF improved subgroup of patients, suggesting that despite having a similar LV EF the underlying pathophysiological substrate of HFmrEF is not uniform and depends on the underlying etiology for the HF.

This study has a number of limitations that warrant discussion. First, clinical registries suffer from a number of limitations including referral biases, as well as inherent limitations on the types of data that are collected. In this regard, since we did not record longitudinal studies of LV function, we performed a retrospective review of echocardiograms that were performed prior to enrollment of the patient into the registry, and we only included those patients whose ejection fraction could be confirmed. Second, there is no consensus on the appropriate definition for the cut-off value for EF for patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF, and different studies have used different cut-offs.8, 9, 12, 13 Here we used a range of EFs between 40–50% to define the HFmrEF population, which is similar to the range of values defined as intermediary by the American Heart Association.1 Lastly, the numbers of patients in the HFmrEF deteriorated and HFmrEF unchanged group were relatively small, which may have precluded the ability to discern statistically significant differences in these subgroups.

Conclusions

Patients with HF with a mid-range/mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) represent a growing proportion of patients who are encountered in clinical practice. Here we show that obtaining information with regard to the historical course of the patient’s prior LV EF allows one to identify a distinct pathophysiological substrate and clinical course for this heterogeneous group of patients. Given what is currently known with regard to the clinical course of HFrEF patients who respond to medical therapy, the observation that the HFmrEF improved patients had better clinical outcomes when compared to age and gender matched patients with HFrEF is probably not that surprising. However, an important finding in this study is that the HFmrEF improved patients have clinical event rates of death, cardiac transplantation and cardiac hospitalization that are similar to those observed in HFpEF patients. Thus, the HFmrEF improved patients still have clinical heart failure despite a significant recovery of LV function. While this study does not address the issue of whether the HFmrEF improved patients should be maintained on evidence based medical therapies for heart failure after their EF is > 40%, the observation that HFmrEF patients still have significant heart failure events would argue against stopping their medications. Although the HFmrEF deteriorated patients represented a relatively smaller proportion of patients in this study, our results suggest that these patients have a pathophysiological substrate that overlaps patients with HFpEF, and therefore suggests that this subgroup of HFmrEF patients may not respond to medical therapies that are currently used for patients with HFrEF. Further studies will be necessary to address this question. Apart from the clinical significance of the above findings, the results of this study suggest that we may have reached an inflection point in the modern era of HF therapeutics with respect to relying only on LV EF to categorize the pathophysiology of HF, and that we need to establish a new taxonomy for classifying HF patients that leverages the advances in biomedical science and incorporates the underlying molecular and environmental causes of HF in concert with the conventional assessment of LV structure and function.17

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Mentors in Medicine program at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the funds from the NIH RC2-HL102222.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punnoose LR, Givertz MM, Lewis EF, Pratibhu P, Stevenson LW, Desai AS. Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction: a distinct clinical entity. J Card Fail. 2011;17:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam CS, Solomon SD. The middle child in heart failure: heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (40–50%) Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1049–55. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu CM, Chau E, Sanderson JE, Fan K, Tang MO, Fung WH, Lin H, Kong SL, Lam YM, Hill MR, Lau CP. Tissue Doppler echocardiographic evidence of reverse remodeling and improved synchronicity by simultaneously delaying regional contraction after biventricular pacing therapy in heart failure. Circulation. 2002;105:438–445. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yip G, Wang M, Zhang Y, Fung JW, Ho PY, Sanderson JE. Left ventricular long axis function in diastolic heart failure is reduced in both diastole and systole: time for a redefinition? Heart. 2002;87:121–5. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellawell JL, Margulies KB. Myocardial Reverse Remodeling. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;20:172–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joseph SM, Novak E, Arnold SV, Jones PG, Khattak H, Platts AE, Davila-Roman V, Mann DL, Spertus JA. Comparable Performance of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Heart Failure Patients with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1139–1146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Butler J, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J. 2014;168:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coles AH, Fisher K, Darling C, Yarzebski J, McManus DD, Gore JM, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Long-term survival for patients with acute decompensated heart failure according to ejection fraction findings. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbs FD, Roalfe AK, Davis RC, Davies MK, Hare R. Prognosis of all-cause heart failure and borderline left ventricular systolic dysfunction: 5 year mortality follow-up of the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening Study (ECHOES) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1128–1134. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, Authors/Task Force M, Document R 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coles AH, Tisminetzky M, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM, Darling CE, Goldberg RJ. Magnitude of and Prognostic Factors Associated With 1-Year Mortality After Hospital Discharge for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Based on Ejection Fraction Findings. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002303. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadruz W, Jr, West E, Santos M, Skali H, Groarke JD, Forman DE, Shah AM. Heart Failure and Midrange Ejection Fraction: Implications of Recovered Ejection Fraction for Exercise Tolerance and Outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002826. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basuray A, French B, Ky B, Vorovich E, Olt C, Sweitzer NK, Cappola TP, Fang JC. Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction: clinical description, biomarkers, and outcomes. Circulation. 2014;129:2380–2387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann DL, Barger PM, Burkhoff D. Myocardial recovery: myth, magic or molecular target? J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2465–2472. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlo M, Stolfo D, Anzini M, Negri F, Pinamonti B, Barbati G, Ramani F, Lenarda AD, Sinagra G. Persistent recovery of normal left ventricular function and dimension in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy during long-term follow-up: does real healing exist? J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001504. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann DL. Is It Time for a New Taxonomy for Heart Failure? J Card Fail. 2016;22:710–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.07.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, 3rd, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, Marino P, Oh JK, Popescu BA, Waggoner AD. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:277–314. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.