Abstract

Background

Advance care planning (ACP) promotes care consistent with patient wishes. Medical education should teach how to initiate value-based ACP conversations.

Objective

To develop and evaluate an ACP educational session to teach medical students a value-based ACP process and to encourage students to take personal ACP action steps.

Design

Groups of third-year medical students participated in a 75-minute session using personal reflection and discussion framed by The Conversation Starter Kit. The Conversation Project is a free resource designed to help individuals and families express their wishes for end-of-life care.

Setting and Participants

One hundred twenty-seven US third-year medical students participated in the session.

Measurements

Student evaluations immediately after the session and 1 month later via electronic survey.

Results

More than 90% of students positively evaluated the educational value of the session, including rating highly the opportunities to reflect on their own ACP and to use The Conversation Starter Kit. Many students (65%) reported prior ACP conversations. After the session, 73% reported plans to discuss ACP, 91% had thought about preferences for future medical care, and 39% had chosen a medical decision maker. Only a minority had completed an advance directive (14%) or talked with their health-care provider (1%). One month later, there was no evidence that the session increased students’ actions regarding these same ACP action steps.

Conclusion

A value-based ACP educational session using The Conversation Starter Kit successfully engaged medical students in learning about ACP conversations, both professionally and personally. This session may help students initiate conversations for themselves and their patients.

Keywords: advance care planning, medical student, medical education, palliative care, patient–provider communication, person-centered learning

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) conversations are beneficial for promoting future care that is consistent with the patient’s life goals and personal values, especially in end-of-life illnesses.1 Advance care planning can help decrease anxiety and emotional distress for patients and their families.2 However, completing advance directives alone does not ensure positive patient outcomes.3,4 Effective ACP includes multiple value-based conversations with loved ones and health-care professionals.5,6 Because many patients are reluctant to initiate these conversations, physicians and other health-care providers need to be skilled in initiating and conducting ACP counseling con-verations.7 However, many physicians feel inadequately prepared to initiate ACP conversations and employ ineffective tactics for starting these conversations.8,9

To effectively prepare physicians to initiate ACP discussions with patients, undergraduate medical education should provide didactics to teach students about value-based ACP conversations.10,11 Successful curricula should emphasize methods of initiating ACP conversations, understanding personal values and preferences of future medical care, and encouraging thorough and ongoing communication between patients and their loved ones.12 One ACP curriculum requires medical students to complete advance directives with another person such as a family member or a patient.13 The curriculum suggests that students learn more effectively through the process of completing an advance directive with another individual compared to learning about advance directives in a lecture setting. Another model found that second-year medical students who used a computer-based decision aid to help patients with ACP found that the use of the decision aid improved students’ knowledge, skills, and satisfaction related to ACP.14 A third strategy has focused on having students complete their own advance directives as a means of learning about the ACP process and associated documentation.15 A potential limitation to these approaches is the focus on completing written advance directives rather than training in how to motivate and engage individuals in ACP conversations focused on discussing values with loved ones and health-care providers.

To address the need to train medical students in how to initiate and counsel patients in value-based ACP conversations rather than the mechanics alone, we developed an ACP educational session for third-year medical students focused on discussing ACP. This session teaches the characteristics of ACP conversations and value-based decision-making using The Conversation Project as an educational resource.16 The content of the Conversation Starter Kit, a free downloadable handout, emphasizes a value-based ACP process (eg, “What matters to me is still being able to …”) rather than procedure-based discussions (eg, “Do you want cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]?”). Using an experiential learning approach, including personal reflection and small group discussions, students consider and discuss their own ACP preferences as a way of experiencing a value-based ACP conversation. By encouraging students to engage in their own ACP process during the session, we propose that students will learn more effectively through the opportunity for direct application as part of the teaching process.17 In addition, the process of considering and completing their own ACP may assist students in preparing to begin these discussions with patients. This study evaluates the effectiveness of a new ACP approach to educate students about a value-based ACP process, increase students’ individual ACP conversations and actions, and evaluate use of the Conversation Starter Kit.

Methods

Curriculum Overview

As part of the third-year medical curriculum, students attended a 4-hour session on palliative care and end-of-life issues. The session included 3 separate topic areas, including (1) managing nonpain symptoms in advanced illnesses, (2) approaching ACP, and (3) discussing resuscitation preferences. Six sessions were offered and conducted over the study year, with approximately 25 students attending per session. This study focuses on a 75-minute value-based ACP educational session. The curriculum learning objectives included—(1) discussing a value-based decision-making approach to ACP, in contrast to procedure-based approaches, (2) engaging in personal ACP using The Conversation Starter Kit, and (3) exploring benefits and drawbacks of different types of care planning and ACP documentation tools (ie, living will, durable power of attorney for health care, CPR directive, physician orders for life-sustaining treatments). The session used a structured large group discussion on value-based approaches to ACP conversations. Unique to this curriculum, students were asked to work in small groups, using The Conversation Starter Kit, to consider their own, and reflect with others, on individualized value-based decision-making processes and ACP preferences.

Learners

All 150 third-year medical students at the University of Colorado, School of Medicine, participated in this novel curriculum on ACP. Following each session, students completed an evaluation of the session and were asked to consent for use of their evaluation responses in this study. After 1 month, students received an additional survey via e-mail and were again asked to consent to use their answers as part of the study. Individuals who did not provide consent were excluded. This study was approved by the Colorado multiple institutional review board. One hundred twenty-seven students in the 2014 to 2015 third-year medical student class participated and gave consent for their answers to the initial evaluation to be used. At the 1 month follow-up, 81 (64%) students completed the survey and gave consent.

Educational Tool and Approach

The ACP session includes tools from The Conversation Project, www.theconversationproject.org. Specifically, the Conversation Starter Kit is a downloadable handout with questions that encourage reflection about values and preferences in the setting of serious illness or near the end of life. For example, the Starter Kit prompts the reader to consider how much they value quantity versus quality of life and how involved they want their loved ones to be in decision-making.12 The Conversation Project is an organization focused on encouraging families to have conversations about ACP before a medical crisis. The Conversation Project focuses on identifying and incorporating personal values and priorities into ACP conversations with loved ones and health-care providers. The process of identifying values makes it easier to identify care preferences and to communicate these preferences to others.

In this 75-minute session, 1 member of the faculty team (H.D.L., J.A., or J.M.Y.) facilitated the session and engaged students in a group discussion about ACP. The discussion focused students on value-based ACP in contrast to procedure-based ACP. Students were provided with The Conversation Starter Kit handout and viewed a brief online video that introduces The Conversation Project and demonstrates a family having “the conversation.” Students first worked through The Conversation Starter Kit in small groups of 3 to 5 students and discussed questions about their own values related to serious illness. They identified things that they would personally value near the end of life, including the way they would like to receive care as patients. Then, as part of a larger group discussion, students were encouraged to consider their own ACP by sharing personal or family experiences with the group. In addition to the group interaction, students learned about key concepts and legal documents related to ACP (ie, durable power of attorney for health care, living will, out-of-hospital orders), discussing when and how they are used. The session not only presents information but also allows students to reflect upon the information and apply it to themselves. In addition to discussing their ACP experiences, students were given resources to document their ACP preferences if they chose (ie, durable power of attorney for health-care forms and medical living wills).

Evaluation

Following each ACP educational session, students completed an in-person evaluation (Online Supplement 1). The evaluation focused on the usefulness of the session as a means of improving general knowledge of ACP. Midway through the year, students were also asked to evaluate the usefulness of the session in preparing them to address ACP with patients specifically (n = 64, the final 3 cohorts in the academic year). In addition to evaluating the educational value of the session, students were asked about their individual readiness to have conversations about ACP. Students were also asked about concrete ACP actions they had done prior to the session. For example, they were asked about the amount of thought they put into ACP, if they had prior conversations about ACP, if they had prior ACP conversations with their health-care provider, if they had chosen a medical decision maker, and if they had signed official papers with their wishes. One month after the session, students received a 5-question follow-up electronic survey that assessed personal concrete ACP actions (Online Supplement 1).

Results

A total of 127 of the 150 third-year students (85% response rate) completed the immediate postsession evaluations and gave consent for inclusion in this educational project. Eighty-one students completed the 1-month follow-up surveys and consented to the analysis (64% response rate). Each question in the postsession survey and the 1-month follow-up had a 95% or higher completion rate. The types of questions fit broadly into 2 categories—(1) evaluation of the ACP educational curriculum and (2) assessment of students’ personal experiences with ACP conversations.

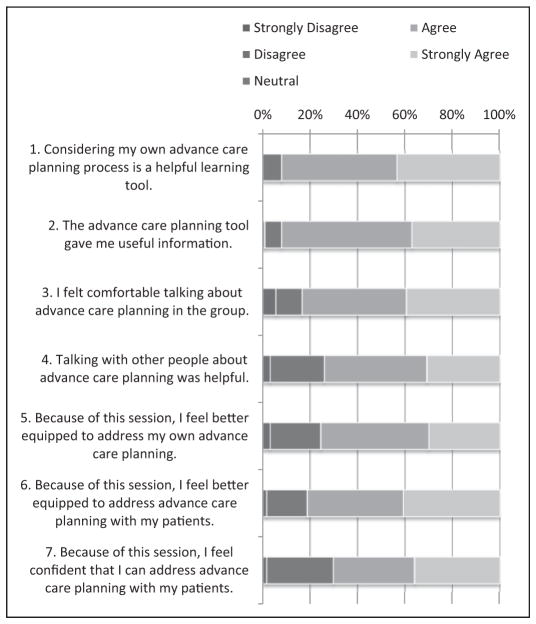

Students’ Perspectives on ACP Educational Session

Overall, students rated the ACP educational session as highly useful for learning about ACP and in preparing them for addressing ACP with patients (Figure 1). In particular, 92% of learners strongly agreed or agreed that considering their personal ACP was a helpful learning tool, and 92% felt that they received useful information from The Conversation Starter Kit. Although a small minority of learners (6%) felt uncomfortable talking in the group discussion, 74% found sharing in a group useful. Seventy-six percent agreed that the session left them better equipped for addressing their own ACP process, and a similar proportion of learners felt better equipped to address ACP with patients (82%, n = 64). A slightly smaller proportion of learners felt confident in their ability to address ACP with patients following the session (70%, n = 64).

Figure 1.

Student perspectives on a value-based advance care planning (ACP) educational session. Students (n = 127) evaluated the value of session related to their own perspectives on ACP. A subset of students (n = 64) evaluated the value of the session for addressing ACP with patients (questions 6–7).

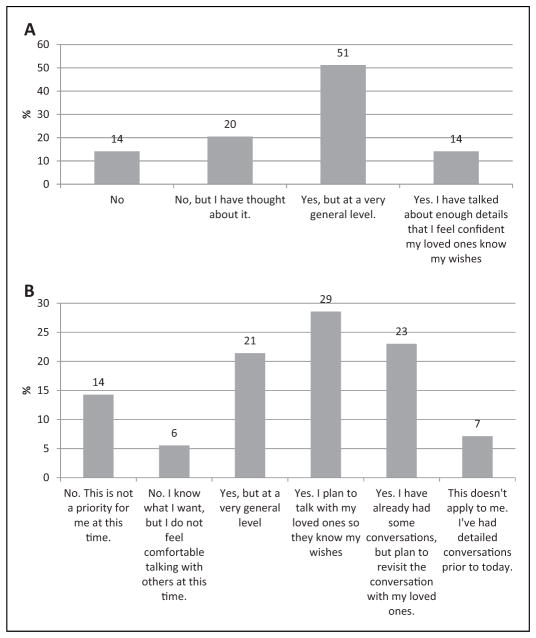

Students’ Personal Experience With ACP Conversations

We assessed the general readiness of students to discuss their own values and preferences by asking about prior ACP conversations, their plans to have a conversation soon, and their readiness for such conversations. Two-thirds (65%) of students reported having personally had a prior conversation related to their own ACP. Of note, only 14% reported that they had detailed conversations where they were confident that their loved ones would know their wishes and 51% reported only having had very general conversations (Figure 2A). When asked about intentions to have an ACP conversation, 73% of students reported planning to have a conversation soon, though in varying levels of detail (Figure 2B). About 20% of students reported having no plans to have an ACP conversation (14% reported it was not a priority for them and 6% reported knowing what they want but feeling uncomfortable having a conversation). In general, students reported feeling prepared for a conversation about ACP (64%), although 7% of students reported feeling unprepared and 20% reported being unsure of their own readiness for ACP conversations.

Figure 2.

Students’ experiences with prior advance care planning (ACP) conversations and plans for future conversations. A, Students (n = 127) reported whether they had prior ACP conversations by answering, “Have you had this kind of conversation with someone close to you about the type of medical care you might want if you were sick or near the end of your life?” B, After the session, students (n = 127) reported whether they planned to have an ACP conversation by answering, “Do you plan to have this conversation soon?”

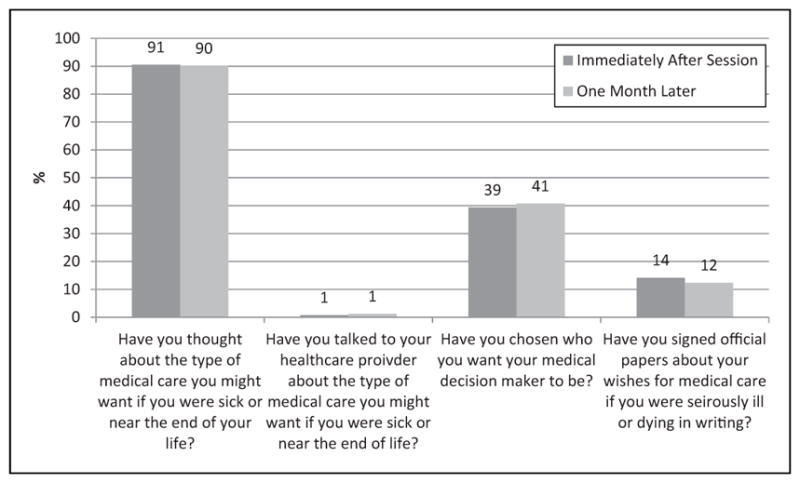

Students’ Actions After the ACP Curriculum

Students reported their experiences with personal concrete ACP actions immediately after the educational session and 1 month later (Figure 3). The majority of students (91% from initial evaluation and 90% from the follow-up survey) reported that they had thought about their own medical care preferences if they were sick or near the end of life. With the exception of 2 students, none of the students had spoken to their health-care provider about future medical care preferences. A minority of students reported having chosen a medical decision maker (39% after initial evaluation and 41% after follow-up survey). Only a small portion of students reported signing official papers about their medical care wishes (14% after initial evaluation and 12% after follow-up). There were no differences in the proportion of students who had taken concrete ACP action steps immediately after the session and 1 month later.

Figure 3.

Student report of personal ACP actions. Proportion of students who reported 4 concrete ACP actions, immediately after the educational session (n = 127, dark gray bars) and 1 month later (n = 81, light gray bars).

Discussion

This novel value-based ACP educational session teaches third-year medical students about ACP through an interactive discussion and asking students to consider their own care preferences. The Conversation Starter Kit and experiential learning approach were well received by students and felt to be an effective way to learn about ACP conversations. Students reflected on their own ACP experiences and preferences during the sessions, and the vast majority reported having thought about their own values related to ACP. Following the session, many students felt prepared to help patients with ACP conversations in the clinical setting, in addition to several who reported plans to discuss their own thoughts related to future preferences with those close to them.

Since 1 of the barriers to good ACP communication between physicians and patients is a mutual reluctance to bring up these conversations, increasing student comfort, or at least willingness to initiate their own ACP discussions, may be a way to improve future communication with their patients. As a means of educating students about ACP, this novel ACP educational session was successful. This curriculum combines experiential learning related to a personal ACP process, education on formal ACP documentation, and practical discussion related to ACP conversations in personal and professional (ie, clinical) contexts. Notably, 65% of the medical students reported having prior conversations with others about their own ACP preferences. This is likely higher than a general population of young adults and may be influenced by social desirability or other response biases. Estimated rates of ACP among healthy young adults are not readily available. Population-based surveys that include adults of all ages, such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, could routinely assess questions related to ACP; Colorado has included ACP-related questions as a state-based module (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, unpublished data). Systematic assessment of ACP conversations for adults of all ages may promote understanding of potential age or generational patterns that affect ACP conversations.

One potential outcome of the educational session was that it might encourage learners to take concrete actions in their own ACP process. Although the session did not have a measureable effect on students’ actions, this finding is not entirely unexpected and may be related to age and overall health status of young adults. Focus groups of undergraduate students aged 18 to 30 years found lack of information to be a major barrier to ACP discussions, with age being a moderating factor.18 That study found that the possibility of incapacitation in the near future was difficult to consider, and therefore a barrier to advance directive completion.

This educational session did not assess students’ potential barriers to taking concrete ACP actions. Practically speaking, this curriculum is conducted on a half-day period during one of the students’ busiest clinical rotations (acute hospital adult care) and the follow-up period was only 1 month. Only 2 students reported having an ACP conversation with their health-care provider. Several students who did not report such a conversation commented that they had no primary care physician at the time of the evaluation, suggesting that 1 barrier to concrete student ACP actions may be the general good health of the population and the resulting limited or inconsistent use of health-care services. Future research, including longitudinal assessments, would help determine whether medical students who have engaged in personal ACP conversations can successfully overcome clinical practice barriers (eg, lack of time, lack of systematic workflows to support ACP)8,19 to engage in value-based ACP counseling with their patients.

This study has several limitations. One key limitation is respondent bias since only 127 of the 150 third-year medical students agreed to participate in the study. This is more prominent for responses to the 1-month follow-up survey, which had a relatively low response rate (64%). Thus, formal statistical analyses were not conducted. To promote survey completion, the students were not asked to provide any identifying information. As a result, the immediate postsession evaluation and 1-month follow-up surveys cannot be linked to conduct a formal pre-to-post comparison. As this educational scholarship project was integrated with the implementation of this new ACP session, no incentives to promote survey completion were offered. The short 1-month follow-up period may also not have provided adequate time to allow students to take ACP action. The second significant limitation is that this study focused solely on students’ response to the ACP session. Self-reported changes are unverifiable and there is no further study yet on the effects of the session on student–patient interactions in a clinical setting or clinical patient outcomes after a value-based ACP session. Another limitation is that the evaluation was expanded midway through the year to ask students whether the session impacted their attitudes regarding initiating ACP conversations with patients. Results from early cohorts are not available. Finally, the study was only conducted at 1 medical school and targeted only 1 health-care discipline. As this educational session can be readily facilitated with free online resources, future projects should focus on adapting a value-based ACP educational session to trainees from other health-care disciplines including nurses, physician assistants, social workers, and chaplains.

In conclusion, this interactive ACP educational session was an effective means of educating students about value-based ACP conversations. It helped students understand how their own values inform their preferences for future medical care and helped them feel better equipped to address ACP with patients. Since many patients expect their health-care providers to initiate discussions related to ACP, this session may help these future physicians to initiate ACP conversations with their patients and provide effective ACP counseling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank 2014 to 2015 University of Colorado School of Medicine third-year medical students for participating in this educational session and completing evaluations for the session and for the purposes of this study. The authors would also like to thank Chris King, MD, for permitting the students’ participation in the study and Ashley Daugherty for helping to coordinate the ACP sessions.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

The online supplement is available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1049909117696245

References

- 1.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teno J, Lynn J, Wenger N, et al. Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: effectiveness with the patient self-determination act and the SUPPORT intervention. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(4):500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lum HD, Sudore RL, Bekelman DB. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(2):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almack K, Cox K, Moghaddam N, Pollock K, Seymour J. After you: conversations between patients and healthcare professionals in planning for end of life care. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahluwalia SC, Bekelman DB, Huynh AK, Prendergast TJ, Shreve S, Lorenz KA. Barriers and strategies to an iterative model of advance care planning communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(8):817–823. doi: 10.1177/1049909114541513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parry R, Land V, Seymour J. How to communicate with patients about future illness progression and end of life: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(4):331–341. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buss MK, Marx ES, Sulmasy DP. The preparedness of students to discuss end-of-life issues with patients. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):418–422. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ury WA, Berkman CS, Weber CM, Pignotti MG, Leipzig RM. Assessing medical students’ training in end-of-life communication: a survey of interns at one urban teaching hospital. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):530–537. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaefer KG, Chittenden EH, Sullivan AM, et al. Raising the bar for the care of seriously ill patients: results of a national survey to define essential palliative care competencies for medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1024–1031. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levi BH, Wilkes M, Der-Martirosian C, Latow P, Robinson M, Green MJ. An interactive exercise in advance care planning for medical students. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(12):1523–1527. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green MJ, Levi BH. Teaching advance care planning to medical students with a computer-based decision aid. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(1):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller PS, Litin SC, Hook CC, Creagan ET, Cha SS, Beckman TJ. A novel advance directives course provides a transformative learning experience for medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22(2):137–141. doi: 10.1080/10401331003656678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Conversation Project. [Accessed February 21, 2017];2016 http://theconversationproject.org/starter-kit/intro/

- 17.Ratanawongsa N, Teherani A, Hauer KE. Third-year medical students’ experiences with dying patients during the internal medicine clerkship: a qualitative study of the informal curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):641–647. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavalieratos D, Ernecoff NC, Keim-Malpass J, Degenholtz HB. Knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of healthy young adults regarding advance care planning: a focus group study of university students in Pittsburgh, USA. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:197. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1575-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.