Abstract

We investigated whether maternal metabolic environment affects mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) from umbilical cord’s Wharton’s Jelly (WJ) on a molecular level, and potentially render them unsuitable for clinical use in multiple recipients. In this pilot study on umbilical cords post partum from healthy non-obese (BMI = 19–25; n = 7) and obese (BMI ≥ 30; n = 7) donors undergoing elective Cesarean section, we found that WJ MSC from obese donors showed slower population doubling and a stronger immunosuppressive activity. Genome-wide DNA methylation of triple positive (CD73+CD90+CD105+) WJ MSCs found 67 genes with at least one CpG site where the methylation difference was ≥0.2 in four or more obese donors. Only one gene, PNPLA7, demonstrated significant difference on methylome, transcriptome and protein level. Although the number of analysed donors is limited, our data suggest that the altered metabolic environment related to excessive body weight might bear consequences on the WJ MSCs.

Introduction

WJ-derived MSCs offer several advantages over those sourced from adult tissues. The material is easily obtained, the cells are more naive and primitive, they have a higher proliferation rate and expansion capability, whilst still maintaining strong immunomodulatory properties1–4. However, evidence suggest that WJ MSCs characteristics may be correlated with biological features of the neonates. MSCs from newborns that are small for gestational age have altered regulation of cell proliferation and oxidative stress5. Therefore, altered in utero metabolic environment might skew fetal MSC towards enhanced adipogenesis and fibrogenesis during intra-utero development and that may result in increased intramuscular fat and connective tissue6. In support of this hypothesis, sera of overweight people, reflecting their metabolic environment, promote in vitro adipocyte differentiation of bone marrow (BM) MSCs and amniotic (A) MSCs from obese women have a higher adipogenic potential7,8. Furthermore, the osteogenic response of undifferentiated BM MSCs to mechanical strain is inversely related to body mass index of the donor9, while the adipose-derived (AD) MSCs isolated from adipose tissue of obese patients have impaired proliferation, clonogenic ability and immune-phenotypes as well as a lower capacity for spontaneous or therapeutic repair than AD MSCs from non-obese, metabolically normal individuals10,11.

Animal studies have supported the observations in humans. A comparative study of AD MSCs isolated from Zucker diabetic fatty rats and their non-diabetic normal weight controls concluded that the impact of type 2 diabetes might compromise the efficiency of stem cell therapy12. BM MSCs isolated from the WNIN/GR-Obese rat model system designed to study obesity with Type 2 diabetes demonstrated a state of “disease memory”, with increased adipogenesis and non-responsiveness to high glucose13. A high-fat diet has been shown to increase interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production by increasing nuclear factor (NF)-κB and attenuating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- (PPAR)-γ expression in BM MSCs of young Wistar rats14. Furthermore, diet-induced obesity altered the differentiation potential of the MSCs isolated from mouse bone marrow, adipose tissue and infrapatellar fat pad15.

The molecular mechanisms through which the altered intrauterine metabolic environment of a pregnant woman with excessive body weight might predispose offspring to long-term adiposity are unknown. Several recent studies suggested that epigenetic modifications could play a crucial role16–20. To evaluate whether the altered metabolic environment related to excessive body weight might bear consequences for the use of umbilical cord WJ MSCs in cellular therapy, we compared their growth, differentiation propensity into adipo-, chondro- and osteogenic lineages, immunomodulatory effect, genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptome analyses in early passages of WJ MSCs isolated from healthy non-obese and obese donors (Figure S1).

Results

Growth and phenotypic profile of WJ MSCs from obese and non-obese donors show significant differences in population doubling (PD) time and CD56 expression

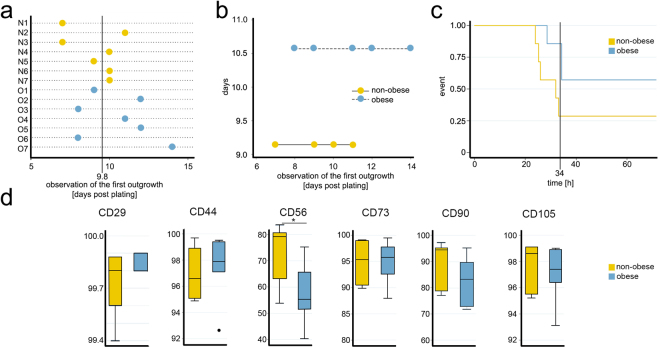

Initial outgrowth of WJ-MSCs from explants of the control group was evident on Day 7–11, whereas from the obese group on Day 8–14 (Fig. 1A). The mean (±standard deviation, SD) time to the first observation of outgrowth was 9.1 (±1.5) days in the non-obese donors and 10.5 (±2.2) days in the obese donors. However, the difference between the obese and non-obese groups in terms of the initial outgrowth of the cells was not significant by Mann-Whitney test (p = 0.220). Analysis based on the Poisson model showed that the timing of initial outgrowth in the non-obese group was earlier than in the obese group but was not significantly different (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Significant differences between WJ MSCs isolated form non-obese and obese donors. (a) The WJ MSCs from the control groups showed an initial outgrowth on day 7 for donors N1 and N3 and on day 10 for donors N4, N6, and N7. Initial outgrowth for donors N5 and N2 was observed on days 9 and 11, respectively. In the cultures of explants from the obese group an initial outgrowth was evident on day 8 from donors O3 and O6 and on day 12 from donors O2 and O5. Donors O1 and O4 showed initial outgrowth on days 9 and 11, respectively. The explant culture from donor O7 was the slowest to establish and expand, showing the initial outgrowth on day 14. (b) Poisson model showed that the rate of initial outgrowth in the non-obese group (9.1 ± 1.5 days) was earlier than in the obese group (10.5 ± 2.2) but still not significant. The 95% confidence interval of the incidence rate ratio was 1.15 (0.827 to 1.61; p = 0.395). (c) The Kaplan-Meier curve using overall median of 34 h indicates that time to doubling of the WJ MSC from non-obese donors is superior. Stratified log-rank test for equality of functions has shown that the difference in the median time to doubling within the first 34 h is statistically significant (p = 0.048). (d) Expression profile of MSC surface markers. Mann-Whitney did not show significant difference between subpopulations of the two groups positive for CD29 (p = 0.268), CD44 (p = 0.482), CD73 (p = 0.949), CD90 (p = 0.249), and CD105 (p = 0.608), whereas CD56+ subpopulation was significantly smaller (p = 0.025) in the obese group (*p ≤ 0.05).

The median (range) PD time of the WJ-MSCs between PD1 and PD2 was 32 (24.0 to 71.6) h in the non-obese group and 48 (28.5 to 96.0) h in the obese group. The overall median time to doubling was 34.2 (24.0 to 96.0) h. These results suggest that the population doubling time of cells from the obese group was somewhat longer than that of cells from the non-obese group; however, the difference was not significant per Mann-Whitney test (p = 0.084). The Kaplan-Meier log-rank test used to compare the cell doubling time in both groups in the first 34 h (overall median PD time) suggested that the difference in the time taken to double within the first 34 h between the groups was significant (p = 0.048); the PD time of the cells from the obese group was significantly longer than that of the cells from the non-obese group (Fig. 1C).

Although the majority of the cells in both groups were positive for all standard MSC markers (CD29, CD56, CD44, CD73, CD90 and CD105), Mann-Whitney testing of the expression profiles demonstrated significant difference between non-obese and obese donors in expression level of CD56, which showed significantly lower expression levels in cells from obese than non-obese donors (p = 0.025) (Fig. 1D). Both groups were negative for CD271 and MSCA-1 and for the haematopoietic cell surface markers CD45 and CD34 (data not shown). To avoid adding bias and to match the samples as closely as possible, all subsequent analyses were performed on the sorted triple positive (CD73+CD90+CD105+) WJ MSCs.

WJ MSCs from obese and non-obese donors have a similar differentiation propensity

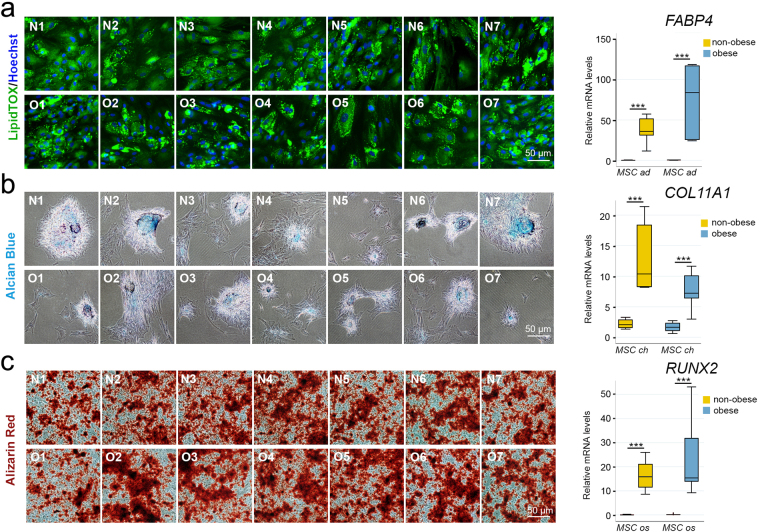

Next, we assessed adipo-, chondro- and osteogenic differentiation potential of triple positive (CD73+CD90+CD105+) WJ MSCs from the two groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Propensity towards adipogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation is similar between WJ MSCs from obese and non-obese donors. (a) Proadipogenic differentiation. Intracellular lipid droplets visualized with a fluorescent LipidTOX™ Green in WJ MSC from non-obese (N1–7) and obese donors (O1–7) following proadipogenic differentiation (left). Per Wilcoxon signed rank test, the expression level of adipogenic marker FABP4, as assessed by qPCR, was significantly higher in differentiated cells than in undifferentiated cells (***p ≤ 0.001) indicating adipogenesis (right). However, Mann-Whitney test did not find significant the overall differences between the obese and non-obese groups (p = 0.110). Analysis based on the Bootstrap model showed that the incidence rate ratio at the 95% confidence interval was −48.1 (−82.9 to 11.7). ad, cells undergoing proadipogenic differentiation; MSC, undifferentiated cells. (b) Prochondrogenic differentiation. Extracellular matrix rich in chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycans assessed with Alcian blue, pH 1.0 staining of WJ MSC from non-obese (N1–7) and obese (O1–7) donors following prochondrogenic differentiation (left). Per Wilcoxon signed rank test, the expression of chondrogenic marker COLL11A1, as assessed by qPCR, showed significant increase in WJ MSC from both non-obese and obese donors upon differentiation (***p ≤ 0.001), indicating chondrogenesis (right). However, Mann-Whitney test did not find significant differences between obese and non-obese groups (p = 0.063). Analysis based on the Bootstrap model showed that 95% confidence interval of the incidence rate ratio was 3.13 (−1.36 to 11.7). ch, cells undergoing prochondrogenic differentiation; MSC, undifferentiated cells. (c) Proosteogenic differentiation. Extracellular calcium deposits stained with Alizarin Red in WJ MSC from non-obese (N1–7) and obese (O1–7) donors following proosteogenic differentiation (left). Expression of osteogenic marker RUNX2 assessed by qPCR showed significant increase in WJ MSC from both non-obese and obese donors upon differentiation (***p ≤ 0.001) indicating osteogenesis (right). However, Mann-Whitney test did not find differences between the groups significant (p = 0.482). Analysis based on the Bootstrap model showed that the 95% confidence interval of the incidence rate ratio was 0.54 (−15.4 to 10.4). MSC, undifferentiated cells; os, cells undergoing proosteogenic differentiation.

Lipid droplets were positively stained with LipidTOX dye in all samples after two weeks of exposure to proadipogenic medium (Figs 2A and S2). Per Wilcoxon signed rank test, mRNA expression level (mean ± SD) of the adipogenic marker fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) was significantly higher in differentiated cells (56.5 ± 34.7) than in undifferentiated cells 0.23 ± 0.12 (***p = 0.001), confirming adipogenesis. Mann-Whitney test did not find significant the overall differences between the obese and non-obese groups (p = 0.110).

Similarly, following two weeks of exposure to chondrogenic medium, cells from all donors were stained positively with Alcian blue and chondrogenic marker collagen type XI alpha 1 chain (COL11A1) expression (Fig. 2B). Per Wilcoxon signed rank test, the mRNA expression level of COL11A1 (mean ± SD) was significantly higher in differentiated (10.3 ± 4.94) than in undifferentiated cells 1.92 ± 0.74 (***p = 0.001), indicating the chondrogenesis. Mann-Whitney test did not find significant differences between obese and non-obese groups (p = 0.063).

Finally, we assessed osteogenic potential with Alizarin red staining and measuring mRNA levels of runt related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), osteogenic-specific marker (Fig. 2C). The significant differences between the differentiated 19.7 ± 11.6 and undifferentiated cells 0.10 ± 0.09 (***, p = 0.001) per Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated osteogenesis. Mann-Whitney test did not find differences between the groups significant (p = 0.482).

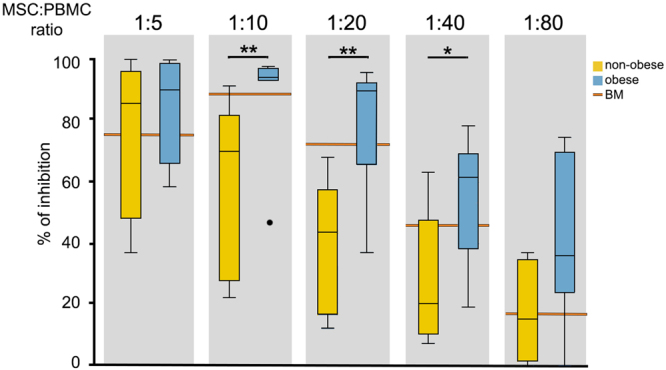

WJ MSCs from obese donors exhibit a stronger immunomodulatory potential than those from non-obese donors

Since MSC have the ability of exerting potent immunosuppressive and immunoregulatory effects21–23, we investigated whether the altered metabolic environment of the obese pregnancies affects WJ MSC immunomodulatory properties. Triple positive (CD73+CD90+CD105+) WJ MSCs from both non-obese (n = 7) and obese (n = 7) donors were compared for their ability to inhibit phytohemagglutinin A (PHA)-induced proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). The data were analysed using Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test. Confidence interval for median difference was calculated using Bootstrap method. A significant difference was observed when the cells were cultured in 1:10, 1:20 and 1:40 ratio, but not 1:5 or 1:80 suggesting that WJ MSC from obese donors were more immunosuppressive than those from normal controls and paralleled the immunomodulatory capabilities of BM MSCs (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

WJ MSCs from obese donor show significantly higher immunomodulatory potential than the cells from non-obese donors. WJ MSC from obese donors (n = 7) inhibited phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human PBMC proliferation in dose-dependent manner in a similar fashion as the BM MSC. The data were analysed using Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test. Confidence interval for median difference was calculated using Bootstrap method. Immunomodulatory potential of the cells from non-obese donors (n = 7) was significantly lower at 1:10 (**p ≤ 0.01), 1:20 (**p ≤ 0.01) and 1:40 (*p ≤ 0.05) MSC:PBMC ratios.

Effect of maternal obesity on the DNA methylation profile of WJ MSCs

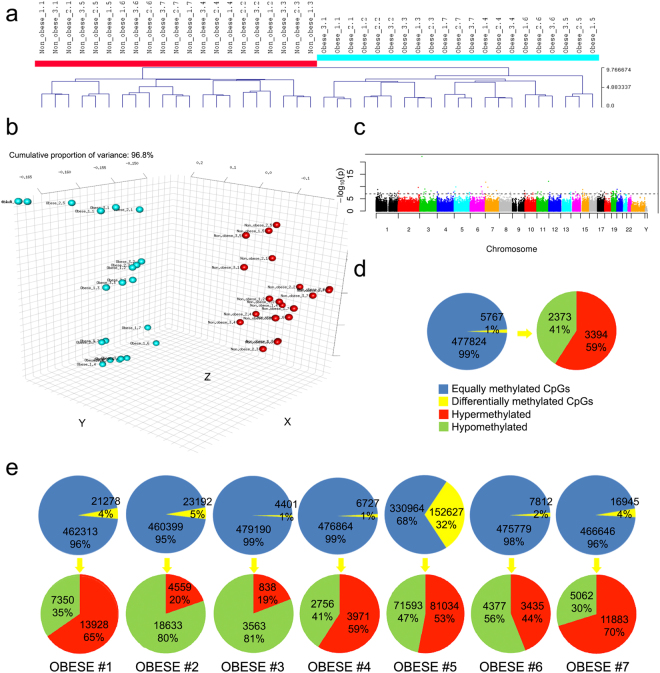

To investigate whether differences in cell proliferation, subpopulation profile and immunomodulatory potential reflect differences in epigenetic regulation of gene expression due to altered metabolic environment, we analysed whole epigenome DNA methylation using Illumina’s 450k array.

On average, the arrays passed the quality control thresholds (Figure S3). Given that there are three technical replicate arrays per sample, it would have been feasible to exclude the arrays with poorer performance without a reduction in the number of represented donors. However, given the hierarchical clustering result (triplicates of technical replicates always immediately clustered together), the inclusion of the arrays with poorer performance does not seem to have had much of an effect on the analysis. Hierarchical clustering of the arrays resulted in clearly distinct clusters of WJ MSCs isolated from samples of non-obese versus obese donors (Fig. 4A,B), while the technical triplicates for each sample were immediately clustered together. A Manhattan plot displaying the significance of the associations by chromosomes indicated that the altered methylation state was distributed across all chromosomes (Fig. 4C). Chromosome 1 harboured most of the differentially methylated CpGs, and Chromosome Y the fewest. The majority of the differentially methylated CpGs were either located in gene bodies (38% of hypermethylated and 31% of hypomethylated) or were intergenic (29% of hypermethylated and 34% of hypomethylated) (Figure S4). Based on the CpG content of the local genomic neighbourhood, the differentially methylated CpGs were isolated CpGs in regions defined as “open sea regions” (43% of hypermethylated and 47% of hypomethylated).

Figure 4.

DNA methylation portrait. (a) Hierarchical clustering analysis based on epigenome-wide DNA methylation shows that the WJ MSC isolated from non-obese (n = 7) and obese donors (n = 7) cluster separately. WJ SMC from each donor were analysed in triplicates. (b) Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated that the WJ MSC from non-obese and obese donors formed separate clusters. (c) Manhattan plot indicates that altered methylation state was spread across all chromosomes. (d) Graphic showing percentage of differentially methylated CpG sites between averages of non-obese (n = 7) and obese (n = 7) samples. (e) Comparative analyses of WJ MSC from each obese donor vs. an average from all non-obese donors. Statistically significant alteration of methylation state was seen in 1–5% of all CpG sites in 6 out of 7 donors, whereas 32% of CpG sites were different in the samples from obese donor #5.

Comparison of the average of all non-obese with the average of all obese samples showed that about 1% of the assayed CpG sites (5767) were significantly differentially methylated (≥20% difference in methylation). Of these sites, 41% (2373) were hypomethylated and 59% (3394) were hypermethylated (Fig. 4D). We then compared DNA methylation between each individual obese donor and the group of non-obese donors (Fig. 4E). The differences in terms of the fraction of differentially methylated CpGs ranged from 1% (donors #3 and #4) to 32% (donor #5). Among CpG sites with significantly different methylation, hypomethylation was predominant in three donors (donor #2: 80%, donor #3: 81% and donor #6: 56%), while hypermethylation was more frequent in four donors (donor #1: 65%, donor #4: 59%, donor #5: 53% and donor #7: 70%). The statistical power for detecting a 20% methylation difference in our data set of 21 versus 21 samples (7 non-obese versus 7 obese donors, each in triplicate; Fig. 4A–C) was around 99%. The same was true of the 3 versus 21 samples comparison (one obese versus 7 non-obese donors, each in triplicate; Fig. 4D). Although the number of samples analysed is limited, our data suggest that maternal obesity might have a lasting effect on the DNA methylation profile of WJ MSCs isolated from umbilical cord explants and cultured in vitro for at least one passage.

Next, we looked for CpG sites where DNA methylation might be influenced by the altered metabolic environment of obese donors. The criterion was that the particular CpG site had to be significantly differentially methylated in four or more donors. We observed such CpG sites in 67 genes (Figure S4). Six out of seven obese donors shared 3 genes (NTM, SIM2 and STT3A), five out of seven shared 22 genes and four out of seven shared 42 genes. However, among all these genes, only three had more than one differentially methylated CpG: MAD1L1 (2), TRIM10 (4) and ZNF714 (5). The CpGs in MAD1L1 and TRIM10 were significantly differentially methylated in four donors, and ZNF714 in five donors.

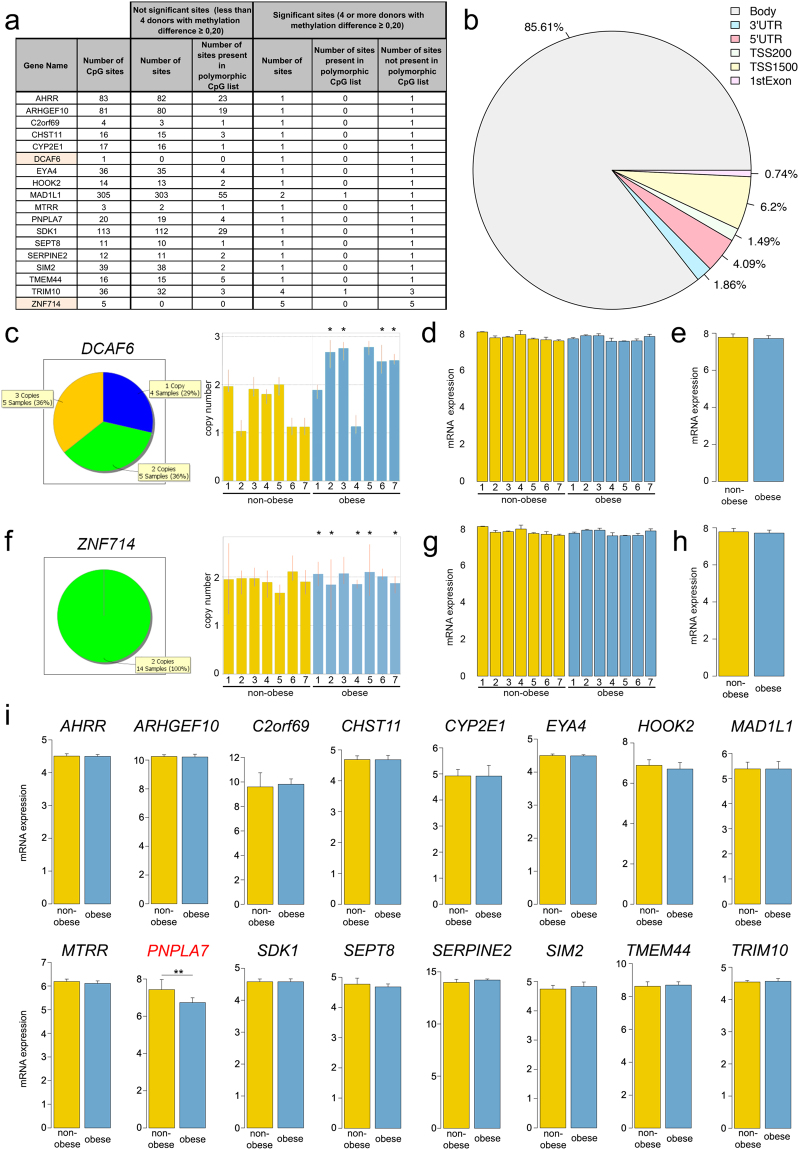

The genes were further filtered based on a list of polymorphic CpG sites24 and segmental duplications25. In 18 out of the 67 genes with differentially methylated CpGs, the CpG sites were in non-polymorphic regions (Fig. 5A). However, two genes (DCAF6 and ZNF714) resided in segmentally duplicated regions. Most of the differentially methylated CpGs were located in the gene body (85.61%), whereas promoter areas (TSS1500, TSS200 and 5′UTR) and the first exon accounted together for 12.53% of sites (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Genes with significantly different DNA methylation in one or more CpG sites in non-polymorphic regions. (a) List of 18 genes that have one of more CpG sites in non-polymorphic regions with difference in methylation ≥20%. DCAF6 and ZNF714, highlighted orange, have variable copy number in genome. (b) Proportion of the locations of CpG sites in the 18 genes. TSS, transcription start site; TSS1500, the sequence region from −200 to −1,500 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site; TSS200, the region from −200 nucleotides upstream to the TSS itself; UTR, untranslated region. (c) TaqMan Copy Number Assays for DCAF6 showed that among 14 donors, four have one copy of the gene (N2, N6, N7 and O4), five have two copies (N1, N3, N4, N5, and O1) and also five have three copies (O2, O3, O5, O6, and O7). All four WJ MSC samples that showed significantly different DCAF6 DNA methylation (*) originated from the donors that have three copies of the gene (O2, O3, O6, and O7). Each sample bar represents the mean calculated copy number and error bars show the standard deviation for three replicates. (d and e) Expression gene array did not detect significant difference DCAF6 mRNA expression in any of the samples indicating that duplicated DCAF6 genes might not be functional. (f) TaqMan Copy Number Assays for ZNF714 showed that all non-obese and obese donors have two copies of the ZNF714 gene. *Five donors that had significantly different DNA methylation of all CpG sites in ZNF714 (O1, O2, O4, O5, and O7). Each sample bar represents the mean calculated copy number and error bars show the standard deviation for three replicates. (g and h) Expression gene array did not detect significant difference ZNF714 mRNA expression in any of the samples indicating that the extra copy of ZNF714 gene might be either functional or not in all donors uniformly. (i) The mRNA expression levels of 16 genes showed no differences in the obese and non-obese groups. The Y axis represents the log2 of the normalized intensity values. The single exception was the PNPLA7 gene, which showed higher expression in the non-obese group than in the obese group (**p ≤ 0.01), the adjusted p-values from Linear Models for Microarray and RNA-Seq Data (limma) statistical test57,58.

Copy number assays analysis of ligand-dependent coactivator of nuclear receptors DDB1 and CUL4 Associated Factor 6 (DCAF6) revealed that donors have variable copy number of the gene: four donors had 1 copy, five donors 2 and five donors 3 copies (Fig. 5C). All donors that displayed significant difference in DCAF6 methylation had three copies of the gene (asterisks), which can explain a difference detected in the methylation array. Indeed, DCAF6 mRNA expression levels did not show any significant difference among individual donors (Fig. 5D) or two groups (Fig. 5E). Similar analysis found that all 14 donors have two copies of the zinc finger protein 714 (ZNF714) gene, including those five that have all five CpG sites differently methylated (asterisks) (Fig. 5F). We could not detect a difference in mRNA levels among individual donors (Fig. 5G) or two groups (Fig. 5H), which suggest that in our case the methylation of these sites per se did not affect gene expression.

To see whether differences in methylation of the CpG sites led to different levels of gene expression, we used a whole transcriptome array. We found 244 regulated genes with fold-change ≥ 1.5 and uncorrected p-value ≤ 0.05 (Figure S5). Six out of seven samples from obese donors clustered together, whereas one (donor O3) clustered with non-obese (Figure S5). According to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (www.genome.jp/kegg/), putative pathways involved are metabolism by cytochrome P450 (6.7% genes), extracellular matrix-receptor interaction (6.0%) and hematopoietic cell lineage (4.7%), whereas REACTOME database (www.reactome.org) suggested involvement of mitotic cell cycle (3.9%) and metabolism of proteins (1.8%) pathways (Figure S6). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (www.geneontology.org) found that among the ten the most significant biological processes involved, nine are linked to cell cycle, which might explain our finding that the cells from non-obese donors proliferate somewhat faster (Figs 1C and S6). Among the six the most significant cellular components involved, five are directly or indirectly linked to extracellular matrix signalling, which matches KEGG database (Figure S6).

Among the remaining 16 genes with significantly different methylation of CpG sites between two groups, only one, Patatin-like Phospholipase Domain containing Protein A 7(PNPLA7), had significantly different mRNA expression levels between non-obese and obese groups (Fig. 5I).

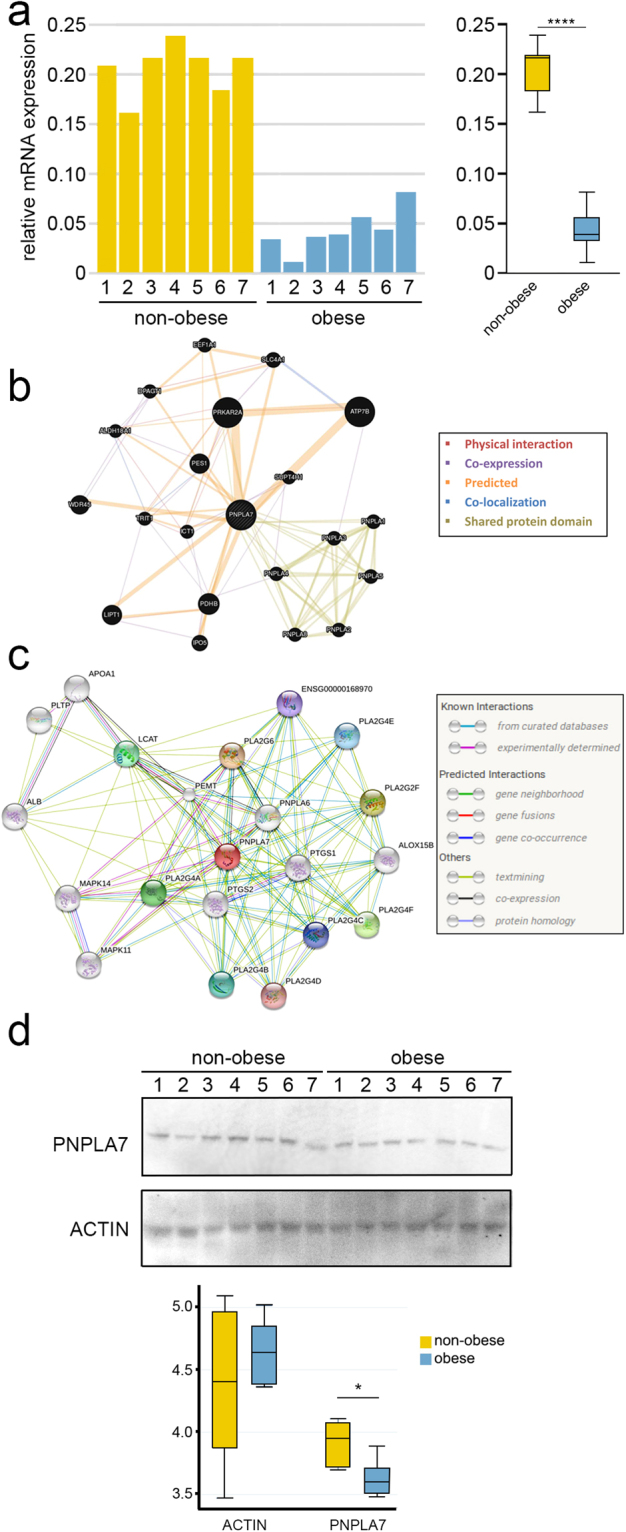

PNPLA7 is downregulated in the samples from obese donors

We confirmed the transcriptome array data with PNPLA7-specific qPCR (Fig. 6A). Mann-Whitney test confirmed that there is indeed a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.001). The mean (±SD) of the gene expression level was 20.6 (±2.55) in the non-obese group and 4.3 (±2.16) in the obese group. Analysis based on the Bootstrap model showed that the 95% confidence interval of the incidence rate ratio was 0.18 (0.15 to 0.21).

Figure 6.

PNPLA7 expression is lower in the WJ MSC from obese donors. (a) The transcriptome array data were validated using PNPLA7-specific qPCR. Mann-Whitney test showed that there is indeed a significant difference between the two groups (****p ≤ 0.0001). The mean ± SD of the gene expression level was 20.6 ± 2.55 in the non-obese group and 4.3 ± 2.16 in the obese group. Analysis based on the Bootstrap model showed that the 95% confidence interval of the incidence rate ratio was 0.18 (0.15 to 0.21). (b) The GeneMANIA Cytoscape plugin PNPLA7 gene function prediction using association approach. (c) Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) predicted protein–protein interactions for PNPLA7. (d) Mann-Whitney test of the Western blot data indicates that the difference between the two groups is also maintained at the protein level (*p ≤ 0.01).

To detect possible known signalling cascades and interaction between PNPLA7 and other genes, we searched the interaction networks using GeneMANIA (Fig. 6B) and String V10.0 (Fig. 6C). According to GeneMANIA, PNPLA7 has predicted interaction with 14 genes including PRKAR2A and ATP7B, whereas PNPLA7 has experimentally determined interactions with MAPK11, MAPK14 and PEMT according to String. However, we did not find any significant difference in gene expression levels in any of the genes highlighted by either of the two programmes.

PNPLA7 is integral component of lysosomal, mitochondrial, nuclear and endoplasmatic reticulum membrane and it is involved in metabolic and developmental processes. Western blot analysis indicated that the difference between the obese and non-obese groups is maintained on the protein level (Figs 6D and S7). The mean (±SD) value of PNPLA7 was lower 0.36 ± 0.01 in the obese group than in the non-obese group 0.39 ± 0.01. Per Mann-Whitney test, the data show that significant difference at the protein level was present between the obese and non-obese groups (p = 0.006). Actin, used as an essay control, showed no significant difference between the obese and non-obese group.

Discussion

Epigenetic alterations that modulate gene expression as consequence of stressful conditions during prenatal development have been convincingly demonstrated in numerous animal and human studies (reviewed in refs17,26–29). The altered metabolic environment in utero due to maternal obesity could be considered stressful to the developing foetus, and indeed, maternal obesity is associated with differential expression of multiple genes30. Although the number of samples we analysed was limited and, power was therefore insufficient to detect small but significant differences, we were still able to detect significant differences between non-obese and obese pregnancies in cell proliferation, immunomodulatory properties, DNA methylation and gene expression of WJ MSCs. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the effects produced by the altered in utero environment were lost during in vitro expansion.

A study demonstrated that specific changes in global methylation in the placenta tissue, but not in the umbilical cord blood, were significantly associated with maternal gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), preeclampsia and obesity during pregnancy31. These findings suggest that the association between maternal obesity and changes in DNA methylation may be tissue-specific. No other study has investigated an association between maternal obesity and DNA methylation in WJ MSCs. The majority studies in this area have used either cord blood or placental samples, often looking for alteration in the methylation of specific genes.

Analysing offspring cord blood, Liu et al.32 have shown that maternal preconception BMI might lead to alterations in offspring DNA methylation in genes relevant to the development of a range of complex chronic diseases. Another study33 found that in cord blood, aryl-hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AHRR) DNA methylation was 2.1% higher in offspring of obese versus normal weight mothers. In our cohort four out of seven obese donors had more than >20% higher methylation of one CpG site in AHRR, though there was no difference in AHRR mRNA levels (Fig. 5i).

Similarly, studies have indicated that obesity during pregnancy affects the DNA methylation of the leptin (LEP) promoter region in placental tissue34, whereas in a mouse model was shown that maternal obesity and diabetes cause widespread epigenetic changes and alter hepatic gene expression in male offspring35. Another study, however, found that maternal GDM is associated with genome-wide DNA methylation changes in both the placenta and the cord blood of the exposed offspring36, contradicting the notion of a tissue-specific association37. The differences between the studies could arise from the use of different methods to assess DNA methylation. For example, methylated DNA immunoprecipitation provides coverage of the whole genome but is limited in resolution, while reduced representation bisulfite sequencing and Nimblegen MethSeq provide single CpG resolution but limited to CpG islands and promoters38.

It should be noted that the differential methylation analysis could be confounded by ethnicity. However, in our case, obese donors that showed a significant difference in PNPLA7 methylation were mixed: two of them were Caucasians (O2, O3), one African Black (O4) and one Caribbean Black (O7), suggesting that the observed difference was not linked to ethnicity.

An interesting finding of our study was that the WJ MSCs from obese donors have a significantly higher immunosuppressive potential than their counterparts from non-obese donors. Obesity is, in general, accompanied by metaflammation, i.e., low-grade and chronic inflammation orchestrated by metabolic cells in response to excess nutrients and energy39,40. It is widely accepted that the MSCs’ immunosuppressive capability is not constitutive but results from the exposure to an inflammatory microenvironment41. The inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that likely are elevated in response to the altered metabolic status of obese donors, for example, TNF-α, may stimulate the WJ MSCs from obese pregnancies to secret higher than normal levels of various immunomodulatory factors and therefore, have a stronger inhibitory effect on the proliferation of PHA-stimulated PBMCs.

A couple of studies investigating correlation between adipogenic potential of WJ MSC and measures of infant body composition at birth found that MSC from infants born to obese mothers exhibit greater potential for adipogenesis31,42. This was linked to altered GSK-3β/β-catenin signalling in MSCs of infants exposed to maternal obesity. We, however, did not find a significant difference in differentiation potential. Several factors can contribute to such discrepancy in results: i) To investigate differentiation, we used triple positive CD73+CD90+CD105+ WJ MSCs, whereas they used mixed population, ii) Adipogenesis has been induced in a different way; in our experiment, the cells were exposed to pro-adipogenic medium continuously for 14 days, whereas in the other study the cells were cultured for 21 days with the three cycles of adipogenic induction medium and the maintenance medium in between31.

Our study singled out PNPLA7, an insulin- and glucose-regulated lysophospholipase that plays a putative role in reducing cellular lysophosphatidic acid (LPA; 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate) under fasting, when lipid stores are mobilised for energy production43–45. LPA is upregulated with adipocyte differentiation and obesity46 and, therefore, it does not come as a surprise that PNPLA7 would be then less expressed in samples from obese pregnancies. In addition, it has also been reported that DNA methylation regulates PNPLA7 expression - it is down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines and tissue samples, via the mechanism of transcriptional silencing by promoter hypermethylation47.

PNPLA7 is ubiquitously expressed transmembrane protein associated with lysosomes, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum as well as microtubule organizing center48. However, our knowledge about PNPLA7 is still quite limited. Resolving specific role of PNPLA7 expression and activity in metabolic pathways associated with obesity will require significant additional work, the most importantly gain- and loss-of-function studies in vitro and in vivo. Against the background of the published data, our pilot study suggested that if significant differences in the PNPLA7 DNA methylation or expression could be correlated with onset of obesity in childhood, PNPLA7 expression might be used as a potential biomarker. Whereas a correlation between body weight and PNPLA7 expression is general or restricted only to WJ MSC remains to be seen.

Although the number of analysed donors is limited, our data suggest that the effects of maternal obesity on WJ MSCs isolated from umbilical cord explants related to use of these cells for allogeneic therapy are relatively restricted and a concern that the abnormal metabolic environment related to excessive body weight might bear consequences for the use of umbilical cord MSCs in cellular therapy may not be warranted.

Experimental section

Human samples

Collection of the samples was described previously49. Briefly, following informed consent, for this study we recruited seven healthy obese pregnant women with BMI ≥ 30 and seven healthy non-obese with BMI between 21 and 25 at the gestational age of 37 weeks (Figure S1). All non-obese women were Caucasians aged between 35 and 43, whereas among the obese group, three were Caucasians (aged 34, 35 and 39) and four were Black, two African (aged 34 and 38) and two Caribbean (aged 28 and 35). All deliveries were elective Caesarean sections without complications and babies were healthy with no apparent abnormalities.

After inspection, the UC was cut, washed and transported to the laboratory in PBS, supplemented with antibiotics and antimycotics (Life Technologies). The UK National Health Service Research Ethics Committee approved the protocol (12/NE/0371). Clinical grade BM MSCs used as a control in some of the experiments were distributed for compassionate use under the hospital exemption scheme (EC No 1394/2007). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the experiments conformed to the principles set out in the WMA Declaration of Helsinki and the NIH Belmont Report. No financial inducements are offered for donation.

Derivation of MSCs from UC explants and cell culture

The derivation of MSCs from UC explants and standard cell culture were described in detail previously1,49. Briefly, the 5–10 mm2 explants were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone) at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 5% O2. The first harvest from explants is termed passage (P) 0 and following dissociation with TrypLE™ Select (Life Technologies), the cells, 7000/cm2, were re-plated under the same conditions. For DNA methylation analyses, we used the cells from P1 exclusively, and for all other experiments, we used the cells from both P1 and P2.

Flow cytometry analyses

Flow cytometry analyses were performed as described1. Acute myeloid leukemia cell line Katsumi was used as a CD34+CD45+ control. Antibodies were purchased either form Miltenyi or BD Biosciences.

Differentiation assays

We assessed the differentiation potential of WJ MSCs in three independent experiments. Upon plating into 4-well dishes, the cells were cultured first under standard conditions for 2 days. Medium was then replaced with supplemented complete STEMPRO® adipogenesis, chondrogenesis or osteogenesis differentiating medium (Gibco®, Life Technologies), and replaced on a regular basis for up to three weeks. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 30 min.

After 21-day incubation under differentiation conditions, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution for 30 minutes at room temperature (Sigma-Aldrich). Following fixation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated for 30 minutes in a 1:100 dilution of LipidTOXTM Green Neutral Lipid Stain (Invitrogen), which detects cellular lipids. The cells were washed again twice with PBS and mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium supplemented with 1.5 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Labs). The cells were visualized using an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE 50i). For qualitative analysis three areas were randomly chosen for each line. The signals in the images were quantified using ImageJ64 software by calculating the percentage of cellular lipids per cell to obtain the total surface area of LipidTOX-positive droplets per number of nuclei in one field.

Ca2+-containing cells in osteogenic cultures were stained with Alizarin red, whereas the presence of cartilage-related glycosaminoglycans in chondrogenic cultures was detected with Alcian blue staining as described1.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with the Roche LightCycler 480 RT PCR Instrument using SYBR Green Mastermix (Roche). Data were collected and analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle method with TATA-box binding protein (TBP) and glucuronidase β (GUSB) as reference genes. Mean ± SD was calculated and statistical analysis was performed using the Prism curve-fitting program (GraphPad Prism, version 6.01). Primers pairs for target genes used were: FABP4, forward 5′-AGCACCATAACCTTAGATGGG-3 and reverse 5′-CGTGGAAGTGACGCCTTTCA-3′; COL11A1 forward 5′-CCAGCGTCTGTTGGTTCAGT-3 and reverse 5′-CAGCTTCCCCTTTCTCTCCT-3′; RUNX2 forward 5′-TTACTTACACCCCGCCAGTC-3′ and reverse 5′-TATGGAGTGCTGCTGGTCTG-3′; PNPLA7 forward 5′-CACTCTTGGGGACTGTGGTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CGGCCGTAAAACATCACTTT-3′; TBP forward 5′-CAGCGTGACTGTGAGTTGCT-3′ and reverse 5′-TGGTTCATGGGGAAAAACAT-3′; GUSB forward 5′-AAACGATTGCAGGGTTTCAC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTCTCGTCGGTGACTGTTCA-3′.

Immunosuppressive assay

The cells were cultured in StemGro, a xeno-free, chemically defined medium (Corning, USA), until they reached 80–90% confluence. The cells were harvested with TrypLE and counted by haemocytometer and evaluated for their viability with Trypan Blue. For the proliferation assay, we used 1 × 106 cells/ml of RPMI medium supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, 10,000 U/ml penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies). Human PBMCs were isolated from leukocyte cones purchased from the National Blood Service, UK. Leukocyte cones were diluted 1:1 with PBS and layered on Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) for density gradient separation. The proliferation assay was carried out in a 96-well plate (Costar) in a total volume of 200 µl per well. MSCs were plated overnight at serial dilutions. PBMCs, 5 × 105/well, stained in 1 µM violet dye from CellTrace cell proliferation kit (Life Technologies) and stimulated with 5 µg/ml of PHA (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to MSCs to obtain co-cultures with increasing MSC/PBMC ratios from 1:5 to 1:80. BM MSCs were run in parallel as a reference. Cultures of stimulated PBMCs without MSCs were used as a positive control, while non-stimulated PBMCs were used as a negative control. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 72 h. The cells were then collected, washed once with PBS, and PBMC proliferation was assessed based on the position and shape of the peak of the cells labelled with the violet dye. Non-stimulated PBMCs were used as guidance for gating in terms of proliferation. In stained cells, the position of the peak increased with increasing dilution. The relative proliferation at each MSC/PBMC ratio was then calculated as a percentage of the proliferation of the positive control by the following formula: A/B × 100, where A is the proliferation at one specific MSC/PBMS ratio and B is the proliferation of the positive control. The percentage of inhibition was then calculated by subtracting the percentage of proliferation from 100 (maximum of inhibition).

DNA methylation

For a comparative analysis of DNA methylation, we directly sorted CD73+CD90+CD105+ WJ MSCs from the first passage into lysis buffer. Genomic DNA was extracted from triple positive MSCs (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+) using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). The DNA was quantified using Qubit™ (Thermo Fisher). Five hundred ng of genomic DNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion using the EZ Zymo DNA Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations for the 450k array. Methylation levels at >480,000 CpG sites throughout the genome were measured using the Infinium Human DNA Methylation 450k BeadChip microarray(Illumina) in triplicate, each array representing an independent bisulfite conversion of a donor sample; performed at the Genomics Facility of the Biomedical Research Centre at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

GenoSplice Technology performed quality control, processing, and further analyses of the data. The data were normalised to adjust for assay type II bias using the Beta-MIxture Quantile dilation (BMIQ) method50 from the Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) R package51. The 450 K array contains 65 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes that do not interrogate methylation, and these were filtered out. In addition, probes having a detection p-value above 0.01 were filtered out, and 1921 probes were thus removed from analysis. The remaining 483591 probes were analysed. The CpGassoc R package52 and Methlab software53 were used for differential methylation analysis together with the HumanMethylation450 v1.2 Manifest File containing CpG annotations. T-statistics were calculated using logit transformed beta values, which can help stabilise the variance54. The logit transform, log(beta/(1-beta)) is equivalent to the log ratio of methylated to unmethylated signal. Multiple testing was performed using the q-value false discovery rate (FDR) method55. The genes with at least one CpG site showing a methylation difference ≥0.20 in 4 or more obese donors were further filtered based on the list of polymorphic CpG sites24 and segmental duplications25.

The methylation data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE74167.

TaqMan® Copy Number Assays

TaqMan Copy Number Assays probes and primers specifically designed to target DCAF6 within intron 17 (essay ID: Hs03384064_cn; Nucleotide sequence variation: nsv946487) and ZNF714 within intron 2 (essay ID: Hs07155647_cn; Nucleotide sequence variation: nsv960811) were used to analyse a panel of genomic DNA samples isolated from WJ MSC of non-obese and obese donors. All probes and primers including TaqMan Copy Reference Assay RNase P (two primers and a probe) and TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific.

Whole Genome Gene-Expression array

The HumanHT-12 Expression BeadChip whole-genome, gene-expression direct hybridization assay system (Illumina) was used at the Genomics Facility of the Biomedical Research Centre at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. as described56. GenoSplice Technology performed quality control, processing, and further analyses of the data. The expression data are now publicly available on GEO under the GSE107214 accession number.

Western blotting

Frozen cell pellets lysed in RIPA buffer (Pierce), 1 × 106 cells/400 µl, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail cOmplete (Roche) were homogenized by passing 10x through 29 G needle and sonicated 2 × 10 sec with sonic dismembranator. Fifteen µl of lysate were mixed with 5 µl of LDS Sample Buffer (Novex® NuPAGE®, Life Technologies), boiled for 5 min, chilled on ice, spun briefly in a table top centrifuge and loaded 15 µl/well of 15-well 4–12% SDS polyacrylamide gel (Novex, NuPAGE, Life Technologies). The proteins were separated in MOPS SDS Running Buffer and transfered from the gel to the 0.2 µm pore size Nitrocellulose membrane (Novex, Life Technologies). The membrane was washed in TBST buffer for 10 min and blocked for 20 min in 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. A2153)/TBST. The membrane was then incubated with rabbit anti-PNPLA7 antibody (Sigma, Cat. No. HPA009130) at dilution 1:1000 (20 ng/ml)/TBST on a rocking platform at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was washed 3 × 10 min in TBST and then incubated with HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) cross absorbed secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) at dilution 1:2500 (20 ng/ml) on a rocking platform at room temperature for 30 min. The membrane was washed 3 × 10 min in TBST. The protein was detected with an enhanced chemiluminsicent Pierce® ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific). The images were detected, recorded and analysed using Intelligent Dark Box LAS-3000 (FUJIFILM)

The membrane was washed in TBST for 10 min, stripped in Restore™ Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific) on a rocking platform at room temperature for 15 min and washed again for 10 min in TBST. Membrane was then incubated with a loading control HRP-conjugated mouse anti-actin antibody BA3R (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h, washed 3 × 10 min in TBST and exposed to Pierce® ECL Western Blotting Substrate. The images were detected, recorded and analysed using Intelligent Dark Box LAS-3000.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Saudi Arabian Government studentship to H. Badraiq and BD Biosciences Research Program Summer 2014 Stem Cell Award to D. Ilic. We thank the National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Centres at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS foundation Trust for use of their facilities, R. Nuamah and A. Saxena, Genomic Core Facility, S. Heck, P.J. Chana and A. Rose, Flow Cytometry Facility, Guy’s Hospital, for technical help. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health. We also thank Dr K Rantell from the Institute for Neurology at the University College London for help with statistics and C. Ogilvie from the Genetics Centre at Guy’s Hospital for a critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank to doctors, midwives, nurses and research assistants of the Division of Women’s Health at St. Thomas Hospital, especially to A. Briley, A. Shennan, F. Adegoke and L. Poston who were instrumental in collection of samples. We are especially indebted to patients who donated the cords.

Author Contributions

H.B. performed most of the experiments. A.C. and M.S. designed, performed and interpreted qPCR experiments. A.G., C.M. and C.H. assisted with experiments and interpretation of data. R.Sc. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing. R.Si. and F.D. contributed to the concept and design of the experiments. D.I. conceived and supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-18034-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Devito L, et al. Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stromal/stem cells derived under chemically defined animal product-free low oxygen conditions are rich in MSCA-1(+) subpopulation. Regen. Med. 2014;9:723–732. doi: 10.2217/rme.14.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Omar R, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: the new gold standard for mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies? Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2014;20:523–544. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong CY, et al. Human Wharton’s jelly stem cells have unique transcriptome profiles compared to human embryonic stem cells and other mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troyer DL, Weiss ML. Wharton’s jelly-derived cells are a primitive stromal cell population. Stem Cells. 2008;26:591–599. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sukarieh R, et al. Molecular pathways reflecting poor intrauterine growth are found in Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29:2287–2301. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du M, Yan X, Tong JF, Zhao J, Zhu MJ. Maternal obesity, inflammation, and fetal skeletal muscle development. Biol. Reprod. 2010;82:4–12. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Bernardo G, et al. Sera of overweight people promote in vitro adipocyte differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014;5:4. doi: 10.1186/scrt393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iaffaldano L, et al. High aminopeptidase N/CD13 levels characterize human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells and drive their increased adipogenic potential in obese women. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:2287–2297. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedl G, Windhager R, Schmidt H, Aigner R. The osteogenic response of undifferentiated human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) to mechanical strain is inversely related to body mass index of the donor. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:491–498. doi: 10.3109/17453670903171883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Girolamo L, et al. Stemness and osteogenic and adipogenic potential are differently impaired in subcutaneous and visceral adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) isolated from obese donors. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013;26(Suppl 1):11–21. doi: 10.1177/03946320130260S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oñate B, et al. The subcutaneous adipose tissue reservoir of functionally active stem cells is reduced in obese patients. FASEB J. 2012;26:4327–4336. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer-Lorente R, Bejar MT, Tous M, Vilahur G, Badimon L. Systems biology approach to identify alterations in the stem cell reservoir of subcutaneous adipose tissue in a rat model of diabetes: effects on differentiation potential and function. Diabetologia. 2014;57:246–256. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madhira SL, et al. Promise(s) of mesenchymal stem cells as an in vitro model system to depict pre-diabetic/diabetic milieu in WNIN/GR-Ob mutant rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortez M, Carmo LS, Rogero MM, Borelli P, Fock RA. A high-fat diet increases IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α production by increasing NF-κB and attenuating PPAR-γ expression in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Inflammation. 2013;36:379–386. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9557-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu CL, Diekman BO, Jain D, Guilak F. Diet-induced obesity alters the differentiation potential of stem cells isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue and infrapatellar fat pad: the effects of free fatty acids. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2013;37:1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp GC, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, offspring DNA methylation and later offspring adiposity: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:1288–1304. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Dijk SJ, Molloy PL, Varinli H, Morrison JL, Muhlhausler BS, Members of EpiSCOPE Epigenetics and human obesity. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2015;39:85–97. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawlor DA, Relton C, Sattar N, Nelson SM. Maternal adiposity - a determinant of perinatal and offspring outcomes? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012;8:679–688. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC. Epigenetic changes in early life and future risk of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond.) 2011;35:72–83. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathers JC. Early nutrition: impact on epigenetics. Forum Nutr. 2007;60:42–48. doi: 10.1159/000107066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marigo I, Dazzi F. The immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Semin. Immunopathol. 2011;33:593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma S, et al. Immunobiology of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:216–225. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Chen X, Cao W, Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/ni.3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YA, et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation 450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8:203–209. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barua S, Junaid MA. Lifestyle, pregnancy and epigenetic effects. Epigenomics. 2015;7:85–102. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaiserman AM. Epigenetic programming by early-life stress: Evidence from human populations. Epigenetic programming by early-life stress: Evidence from human populations. Dev. Dyn. 2015;244:254–265. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki A, de Vega WC, McGowan PO. Biological embedding in mental health: an epigenomic perspective. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013;91:14–21. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2012-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curley JP, Jensen CL, Mashoodh R, Champagne FA. Social influences on neurobiology and behavior: epigenetic effects during development. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:352–371. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carty D, et al. Differential gene expression in obese pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014;4:232–233. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyle KE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from infants born to obese mothers exhibit greater potential for adipogenesis: The Healthy Start BabyBUMP Project. Diabetes. 2016;65:647–659. doi: 10.2337/db15-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, et al. Maternal preconception body mass index and offspring cord blood DNA methylation: exploration of early life origins of disease. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2014;55:223–230. doi: 10.1002/em.21827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burris HH, et al. Offspring DNA methylation of the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor repressor gene is associated with maternal BMI, gestational age, and birth weight. Epigenetics. 2015;10:913–921. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1078963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lesseur C, et al. Maternal obesity and gestational diabetes are associated with placental leptin DNA methylation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;211:654.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li CC, et al. Maternal obesity and diabetes induces latent metabolic defects and widespread epigenetic changes in isogenic mice. Epigenetics. 2013;8:602–611. doi: 10.4161/epi.24656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finer S, et al. Maternal gestational diabetes is associated with genome-wide DNA methylation variation in placenta and cord blood of exposed offspring. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:3021–3029. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nomura Y, et al. Global methylation in the placenta and umbilical cord blood from pregnancies with maternal gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and obesity. Reprod. Sci. 2014;21:131–137. doi: 10.1177/1933719113492206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker DL, et al. DNA methylation profiling: comparison of genome-wide sequencing methods and the Infinium Human Methylation 450 Bead Chip. Epigenomics. 2015;20:1–16. doi: 10.2217/EPI.15.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011;29:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger G, Dixon J. Inflammatory effects of nutritional stimuli: further support for the need for a big picture approach to tackling obesity and chronic disease. Obes. Rev. 2010;11:137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shapiro AL, et al. Nicotinamide Promotes Adipogenesis in Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Is Associated with Neonatal Adiposity: The Healthy Start BabyBUMP Project. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kienesberger PC, Oberer M, Lass A, Zechner R. Mammalian patatin domain containing proteins: a family with diverse lipolytic activities involved in multiple biological functions. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S63–S68. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800082-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kienesberger PC, et al. Identification of an insulin-regulated lysophospholipase with homology to neuropathy target esterase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5908–5917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=PNPLA7 [Accessed Nov 17, 2016].

- 46.Ferry G, et al. Autotaxin is released from adipocytes, catalyzes lysophosphatidic acid synthesis, and activates preadipocyte proliferation. Up-regulated expression with adipocyte differentiation and obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18162–18169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301158200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, et al. Hypermethylation reduces the expression of PNPLA7 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2016;12:670–674. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000130653-PNPLA7/tissue [Accessed Dec 26, 2016].

- 49.Badraiq H, Devito L, Ilic D. Isolation and expansion of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells from umbilical cord under chemically defined conditions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1283:65–71. doi: 10.1007/7651_2014_116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teschendorff AE, et al. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris TJ, et al. Bioinformatics. 2014. ChAMP: 450k Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline; pp. 428–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barfield RT, Kilaru V, Smith AK, Conneely KN. CpGassoc: an R function for analysis of DNA methylation microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1280–1281. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kilaru V, Barfield RT, Schroeder J, Smith AK, Conneely KN. MethLAB: A GUI package for the analysis of array-based DNA methylation data. Epigenetics. 2012;7:225–229. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.3.19284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Du P, et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:587. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. R. Statist. Soc. B. 2002;64:479–498. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petrova A, et al. 3D In vitro model of a functional epidermal permeability barrier from human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:675–689. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phipson B, Lee S, Majewski IJ, Alexander WS, Smyth GK. Robust hyperparameter estimation protects against hypervariable genes and improves power to detect differential expression. Annu. Appl. Stats. 2016;10:946–963. doi: 10.1214/16-AOAS920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.