Abstract

Conditioning-like infarct limitation by enhanced level of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been demonstrated in many animal models of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (MIRI) in vivo. We sought to evaluate the effect of H2S on myocardial infarction across in vivo pre-clinical studies of MIRI using a comprehensive systematic review followed by meta-analysis. Embase, Pubmed and Web of Science were searched for pre-clinical investigation of the effect of H2S on MIRI in vivo. Retained records (6031) were subjected to our pre-defined inclusion criteria then were objectively critiqued. Thirty-two reports were considered eligible to be included in this study and were grouped, based on the time of H2S application, into preconditioning and postconditioning groups. Data were pooled using random effect meta-analysis. We also investigated the possible impact of different experimental variables and the risk of bias on the observed effect size. Preconditioning with H2S (n = 23) caused a significant infarct limitation of − 20.25% (95% CI − 25.02, − 15.47). Similarly, postconditioning with H2S (n = 40) also limited infarct size by − 21.61% (95% CI − 24.17, − 19.05). This cardioprotection was also robust and consistent following sensitivity analyses where none of the pre-defined experimental variables had a significant effect on the observed infarct limitation. H2S shows a significant infarct limitation across in vivo pre-clinical studies of MIRI which include data from 825 animals. This infarct-sparing effect is robust and consistent when H2S is applied before ischemia or at reperfusion, independently on animal size or sulfide source. Validating this infarct limitation using large animals from standard medical therapy background and with co-morbidities should be the way forward.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00395-017-0664-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Preconditioning, Postconditioning, Hydrogen sulfide, Ischemia/reperfusion, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Re-establishing coronary blood flow by either mechanical (primary percutaneous coronary intervention) and/or pharmacological (thrombolytic agents) treatment is essential to limit myocardial damage following acute myocardial ischemia. In industrialised countries, there has been a significant improvement in surgical practice and standard care with an estimate of only one out of four patients with acute ischemic heart attack admitted to early reperfusion intervention dying [41]. Despite this improvement in the survival rate following heart attack, there has also been a considerable increase in long-term co-morbidity and mortality in those patients, which is often a function of the primary infarction. This emphasises the urgent need for treatments which have a therapeutic value for patients with ischemic heart disease. Although an enormous number of mechanical and pharmacological interventions have reported promising infarct-limiting effects experimentally, none has successfully been clinically translated since the first experimental evidence of infarct limitation by ischemic conditioning was reported by Murry et al. [43]. The reasons behind this failure have been discussed in a number of recent reviews and position papers [18, 20, 23] which emphasised three main issues regarding pre-clinical studies. First, there is a “disconnection” between the preclinical and the clinical studies. The complexity of the clinical situation for ischemic heart disease patients needs to be reflected in pre-clinical investigations. This includes common co-morbidities and co-medications which most patients have and are known to modify the response to many cardioprotective manoeuvres experimentally [22, 25]. Second, poor reporting of pre-clinical study methodology and protocols could potentially lead to unnecessary clinical trials [2, 22]. Third, there has been a growing emphasis on interrogating the literature and the careful examination for the pre-clinical evidence using comprehensive, unbiased approaches before conducting any clinical trial [7, 21, 22].

In 1989, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) was first detected in rat brain [61], after long being recognised as a toxic gas. It is now recognised as one of the gasotransmitters family along with nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO). There is an increasing body of evidence demonstrating an essential role of H2S in health and disease [60]. Experimentally, enhanced levels of H2S have been shown to elicit infarct-limiting effect against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (MIRI) in mouse [31], rat [33], rabbit [38] and pig [45]. Promisingly, SG1002, a novel H2S prodrug, has recently successfully completed a phase I clinical trial showing a promising margin of safety in failing heart patients [48]. The cardioprotective mechanism(s) by which H2S induces its cardioprotection are not fully understood. However, there is general consensus that it is mainly through either activating the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway, promoting endogenous antioxidant capacity or preserving mitochondrial integrity [5, 14]. Different approaches have been used to enhance H2S level in vivo with either conventional inorganic sulfide salts, organic H2S donors or phosphodiesterase inhibitors, which we are going to collectively term “H2S boosters” in this analysis. These approaches have been shown to limit various markers of MIRI ex vivo and in vivo.

We conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of H2S on acute myocardial infarction across the in vivo MIRI preclinical studies. In addition, we also performed an additional analysis to provide further insights into the external validity and how the observed infarct limitation by H2S could be influenced by different experimental models or pharmacological approaches. Furthermore, we investigated internal validity of our finding and how reporting quality of included studies and publication bias could have an impact on the results and the general conclusion of our study.

Methodology

Systematic review and data collection

The systematic review was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline [40]. JSB and QGK performed the literature search of the electronic databases Embase, Medline and Web of Science using selected keywords and MeSH terms where appropriately specific to each database (see the supplementary material).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The search included the literature that investigated the effect of H2S on infarct size in in vivo models of MIRI, published between January 01, 2005 and December 16, 2016 considering that the first in vivo report was published in 2006 by Sivarajah et al. [55]. The search only included studies which are available in English. Publications were independently retrieved from the electronic literature and checked for duplication (Fig. 1). The search results were then subjected to the inclusion criteria (Table 1a). Inclusion criteria were developed in accordance with PICOS approach [44]. Reports were included if they characterised the effect of a H2S booster (pre- and/or post-ischemia) versus vehicle or no treatment on the infarct size following MIRI in vivo. Studies were excluded at this stage if there was no documented reperfusion phase or if the coronary artery occlusion was permanent. Reports were also excluded where H2S treatment was continued throughout ischemia/reperfusion protocol, throughout reperfusion phase, or given more than 10 min after the commencement of reperfusion. In vitro or ex vivo studies were also excluded. Disagreements between the primary reviewers were resolved by secondary reviewer (GFB). Studies employing genetically modified animals or animals with co-morbidity, such as diabetes, heart failure, or high blood pressure, were excluded. Experimental studies where an H2S booster was concomitantly administered with other pharmacological treatment, whether it is known for its cardioprotective properties or not, were also not included.

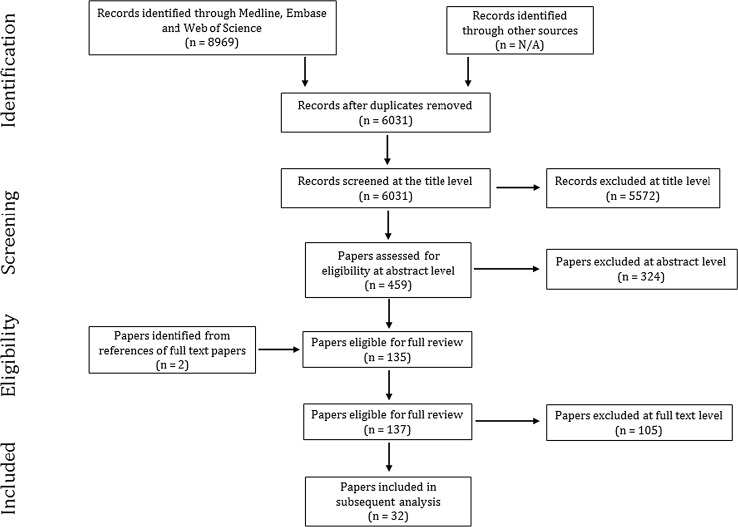

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of systematic review and data selection at different stages

Table 1.

Lists of (a) inclusion criteria and (b) critical appraisal tool

| (a) Inclusion criteria 1. In vivo investigation 2. Documented duration of ischemia and reperfusion 3. Documented time and dose of the exogenous H2S booster(s) 4. Infarct size determined by a recognised method |

| (b) Critical appraisal checklist 1. Characteristics of the animal model (age/weight/sex) 2. Whether the animals were randomly assigned for the control or the treatment group 3. Details about the H2S enhancer used including its name, source, dose, route of administration and the time of intervention 4. Whether the experimental protocol is clearly reported including the duration of ischemia and reperfusion and the end point of interest 5. Infarct size determination is clearly detailed 6. Evaluation of the study design including group size and the statistical power 7. Whether a blind-approach of analysis was adopted by the experimentalist at any stage to carry out the measurements and/or to analyse the data 8. Whether the data were statistically analysed using an appropriate test 9. Whether data interpretation was precise and supports the study conclusion 10. Whether study limitations and/or conflicts of interest were clearly documented |

Critical appraisal

The quality and rigour of studies were examined using the critical appraisal tool (Table 1b) which allowed unbiased, comprehensive evaluation of the studies at full-text level. Corresponding authors were contacted by email to enquire about missing information. Thirty-five papers were considered to meet the inclusion criteria and passed critical appraisal to be included in this study (Fig. 1).

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Our primary outcome was the weighted (unstandardised) mean difference (WMD) in infarct size (IS %) between the experimental group (H2S-treated group) and the control group. We identified 65 independent comparisons in the 35 included articles (Table 2). The number of animals in the control group was corrected based on the number of comparisons for each series of experiments (n/number of comparisons) [59]. We also identified two experimental variables, namely the animal model size and source of H2S, as a secondary outcome which might influence the effect size and heterogeneity.

Table 2.

Summary of the main characteristics of included pre-clinical studies

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bibli et al. [3] a | Mouse | M | 13–15 weeks | NaHS | Post | (100 µg/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Ketamine + xylazine + atropine | SEM | 6 | 52.7 | 4.7 | 6 | 20.1 | 4.3 |

| 2 | Bibli et al. [3] b | Mouse | M and F | 12–15 weeks | NaHS | Post | (100 µg/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Ketamine + xylazine + atropine | SEM | 8 | 42.2 | 2.6 | 8 | 15.5 | 1.1 |

| 3 | Calvert et al. [9] a | Mouse | M | 8–10 weeks | Na2S | Pre | (100 µg/kg) as a bolus 24 h before ischemia | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 9 | 48 | 3 | 10 | 26 | 3 |

| 4 | Calvert et al. [9] b | Mouse | M | 8–10 weeks | Na2S | Pre | (100 µg/kg) as a bolus 24 h before ischemia | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 25 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 9 | 25 | 2 | 7 | 18.2 | 3.3 |

| 5 | Chatzianastasiou et al. [10] a | Mouse | M | 8–12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (1 µmol/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Ketamine + xylazine | SEM | 8 | 37.8 | 3.3 | 8 | 17.8 | 1.8 |

| 6 | Chatzianastasiou et al. [10] b | Mouse | M | 8–12 weeks | GYY4137 | Post | (26.6 µmol/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Ketamine + xylazine | SEM | 8 | 37.8 | 3.3 | 8 | 19.5 | 1.4 |

| 7 | Chatzianastasiou et al. [10] c | Mouse | M | 8–12 weeks | Thiovalin | Post | (4 µmol/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Ketamine + xylazine | SEM | 8 | 37.8 | 3.3 | 8 | 14.4 | 1.2 |

| 8 | Chatzianastasiou et al. [10] d | Mouse | M | 8–12 weeks | AP39 | Post | (250 nmol/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30n | LAD | 2 | NR | Ketamine + xylazine | SEM | 8 | 37.8 | 3.3 | 8 | 16.5 | 2.3 |

| 9 | Chen et al. [11] a | Rat | M | 250–300 g | hs-MB | Post | 6X109/(kg.h) with ultrasonication 5 min before reperfusion until 25 min of reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | STD | 18 | 41.3 | 8.6 | 18 | 25.3 | 6.4 |

| 10 | Chen et al. [11] b | Rat | M | 250–300 g | Na2S | Post | (100 µg/kg) as a bolus at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | STD | 18 | 41.3 | 8.6 | 18 | 26.8 | 3.9 |

| 11 | Das et al. [12] | Mouse | M | 30–34 g | Ad.PKGIα | Pre | (1.5*109 pfu) 96 h before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Pentobarbital sodium | SEM | 6 | 37.5 | 2.2 | 6 | 14.1 | 1.4 |

| 12 | Donnarumma et al. [13] | Mouse | M | 10–14 weeks | Zofenopril | Pre | (10 mg/kg) 8 h before ischemia | PO | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 12 | 47.6 | 4.5 | 9 | 33.6 | 3.7 |

| 13 | Durrant et al. [15] | Mouse | M | 32.2 ± 0.4 g | Na2S | Pre | (100 g/kg) before ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 4 | 45 | 1 | 4 | 12.5 | 0.8 |

| 14 | Elrod et al. [17] a | Mouse | M | 8 weeks | Na2S | Post | (50 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Pentobarbital + ketamine | SEM | 13 | 47.9 | 2.9 | 8 | 13.4 | 1.4 |

| 15 | Elrod et al. [17] b | Mouse | M | 8 weeks | Na2S | Post | (50 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 72 | R | Pentobarbital + ketamine | SEM | 8 | 58.3 | 4.2 | 8 | 29.5 | 4.5 |

| 16 | Jin et al. [29] | Rat | M | 250–300 g | SO2 (NaHSO3 + Na2SO3 | Pre | (1 µmol/kg) given 10 min before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 2 | NR | Urethane | SEM | 16 | 43.0 | 7.0 | 16 | 27.5 | 7.0 |

| 17 | Kang et al. [31] a | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | JK-1 | Post | (50 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 12 | 48 | 1.8 | 12 | 27.5 | 5.5 |

| 18 | Kang et al. [31] b | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | JK-1 | Post | (100 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 12 | 48 | 1.8 | 12 | 17.2 | 2.6 |

| 19 | Kang et al. [31] c | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | JK-2 | Post | (50 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 12 | 45.5 | 3 | 12 | 20.5 | 3.5 |

| 20 | Kang et al. [31] d | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | JK-2 | Post | (100 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 12 | 45.5 | 3 | 12 | 19 | 3.5 |

| 21 | Kang et al. [31] e | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | GYY4137 | Post | (50 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 11 | 49.5 | 4.0 | 10 | 34.0 | 4.0 |

| 22 | Kang et al. [31] f | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | DDT-2 | Post | (1 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 10 | 44.0 | 3.0 | 10 | 40.0 | 4.0 |

| 23 | Kang et al. [30] | Rat | M | 250–300 g | NaHS | Pre | (30 µmol/kg) 30 min before ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Chloral hydrate | SEM | 5 | 35.0 | 5.5 | 5 | 22.5 | 6.0 |

| 24 | Karwi et al. [33] a | Rat | M | 300–350 g | GYY4137 | Post | (266 µmol/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiobutabarbital | SEM | 10 | 52.5 | 4.7 | 8 | 27.9 | 3.8 |

| 25 | Karwi et al. [33] b | Rat | M | 300–350 g | GYY4137 | Post | (266 µmol/kg) as a bolus 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiobutabarbital | SEM | 7 | 56.8 | 3.5 | 7 | 27.6 | 2.0 |

| 26 | Karwi et al. [32] a | Rat | M | 300–350 g | AP39 | Post | (0.1 µmol/kg) 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiobutabarbital | SEM | 10 | 52.8 | 3.9 | 8 | 43.3 | 2.5 |

| 27 | Karwi et al. [32] b | Rat | M | 300–350 g | AP39 | Post | (1 µmol/kg) 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiobutabarbital | SEM | 10 | 52.8 | 3.9 | 8 | 32.1 | 3.3 |

| 28 | Karwi et al. [32] c | Rat | M | 300–350 g | AP39 | Post | (1 µmol/kg) 10 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiobutabarbital | SEM | 11 | 53 | 2.1 | 8 | 30.1 | 2.7 |

| 29 | Li et al. [36] a | Rat | M | 200–250 g | NaHS | Pre | (1.4 µmol/kg) 10 min before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Isoflurane | SEM | 8 | 34.8 | 2.0 | 8 | 27.5 | 2.5 |

| 30 | Li et al. [36] b | Rat | M | 200–250 g | NaHS | Pre | (2.8 µmol/kg) 10 min before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Isoflurane | SEM | 8 | 34.8 | 2.0 | 8 | 22.5 | 0.5 |

| 31 | Li et al. [36] c | Rat | M | 200–250 g | NaHS | Pre | (14 µmol/kg) 10 min before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | isoflurane | SEM | 8 | 34.8 | 2.0 | 8 | 20.0 | 2.0 |

| 32 | Lougiakis et al. [38] | Rabbit | M | 2.8–3.1 kg | 4-OH-TBZ | Post | (1.79 µmol/kg) as a bolus at 20 min of reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 4 | NR | Sodium thiopentone | SEM | 6 | 47.9 | 0.7 | 6 | 24.9 | 0.7 |

| 33 | Osipov et al. [45] | Pig | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (0.2 mg/kg) as a bolus at reperfusion | i.v. | 60 | LAD | 2 | NR | Telazol | SEM | 6 | 42.3 | 5.3 | 6 | 16 | 6.5 |

| 34 | Predmore et al. [49] a | Mouse | M | 8–10 weeks | DATS | Post | (200 µg/kg) as a bolus at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 11 | 53.8 | 3 | 14 | 24.5 | 2.5 |

| 35 | Predmore et al. [49] b | Mouse | M | 8–10 weeks | DATS | Post | (200 µg/kg) 22.5 min before reperfusion | i.p. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 11 | 53.8 | 3 | 6 | 18.8 | 2.0 |

| 36 | Salloum et al. [51] a | Mouse | M | 32.2 ± 0.4 g | Tadalafil | Pre | (1 mg/kg) 1 h before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 40.6 | 2.5 | 6 | 13.2 | 1.7 |

| 37 | Salloum et al. [51] b | Mouse | M and F | 32.2 ± 0.4 g | Tadalafil | Pre | (1 mg/kg) 1 h before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 45 | 2.5 | 6 | 18.1 | 2.1 |

| 38 | Salloum et al. [52] a | Rabbit | M | 2.6–3.2 kg | Cinaciguat | Pre | (1 µg/kg) as a bolus prior to ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 3 | NR | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 37.8 | 0.7 | 6 | 14.1 | 0.9 |

| 39 | Salloum et al. [52] b | Rabbit | M | 2.6–3.2 kg | Cinaciguat | Post | (10 µg/kg) as a bolus 5 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 3 | NR | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 37.0 | 0.5 | 6 | 22 | 2.9 |

| 40 | Salloum et al. [52] c | Mouse | M | 32.2 ± 0.4 g | Cinaciguat | Pre | (10 µg/kg) 30 min before ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 45.5 | 5 | 6 | 10.2 | 3.9 |

| 41 | Salloum et al. [52] d | Mouse | M | 32.2 ± 0.4 g | Cinaciguat | Post | (10 µg/kg) as a bolus 5 min before reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 43.0 | 1.5 | 6 | 16.5 | 3.7 |

| 42 | Salloum et al. [53] | Mouse | M | 28–33 g | Beetroot juice | Pre | (10 g/L) in drinking water for 7 days before ischemia | p.o. | 30 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 46.5 | 3.5 | 6 | 15.8 | 3.2 |

| 43 | Sivarajah et al. []55 | Rat | M | 220–300 g | NaHS | Pre | (3 mg/kg) as a bolus 15 min before ischemia | i.p. | 25 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiopentone | SEM | 10 | 59 | 3.8 | 7 | 44 | 1.9 |

| 44 | Sivarajah et al. [54] | Rat | M | 250–320 g | NaHS | Pre | (3 mg/kg) as a bolus 15 min before ischemia | i.v. | 25 | LAD | 2 | NR | Thiopentone | SEM | 12 | 58.0 | 3.0 | 8 | 45.0 | 3.0 |

| 45 | Snijder et al. [56] | Mouse | M | 6–8 weeks | H2S gas | Pre | (100 ppm) started 30nminutes before ischemia until 5 min of reperfusion | nasal | 30 | LAD | 24 | R | Isoflurane | SEM | 20 | 72.5 | 1.3 | 21 | 27.8 | 0.8 |

| 46 | Testai et al. [57] | Rat | M | 260–350 g | 4CPI | Pre | (0.24 mg/kg) 2 h before ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 39.0 | 2.0 | 6 | 25.0 | 3.0 |

| 47 | Toldo et al. [58] | Mouse | M | 32.4 ± 0.9 g | Na2S | Pre | (100 µg/kg) 1 h before ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 44.4 | 1.6 | 6 | 16.3 | 1.5 |

| 48 | Xie et al. [63] | Rat | M | 270–320 g | ADT | Post | (50 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 4 | NR | Thiobutabarbital | SEM | 10 | 56.4 | 5.5 | 10 | 36.0 | 3.0 |

| 49 | Yao et al. [65] | Rat | M | 8 weeks | NaHS | Pre | (30 µmol/kg) 10 min prior to ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Pentobarbital | SEM | 20 | 32.7 | 12 | 24 | 16.5 | 5.8 |

| 50 | Yao et al. [66] | Rat | M | 250–300 g | NaHS | Pre | (14 µmol/kg/day) for 7 days prior to ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LCA | 2 | NR | Chloral hydrate | STD | 6 | 41.6 | 6.1 | 6 | 30.5 | 4.5 |

| 51 | Zhao et al. [68] a | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | 8a | Post | (1 mg/kg) as a bolus at 22.5 of ischemia | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 14 | 46 | 5.0 | 14 | 28.5 | 6.0 |

| 52 | Zhao et al. [68] b | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | 8I | Post | (500 µg/kg) as a bolus at 22.5 of ischemia | i.v. | 45 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 14 | 51 | 6.0 | 14 | 31.5 | 4.5 |

| 53 | Zhao et al. [69] a | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | NSHD-1 | Post | (50 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital + ketamine | SEM | 12 | 51.0 | 3.0 | 6 | 55.0 | 6.0 |

| 54 | Zhao et al. [69] b | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | NSHD-1 | Post | (100 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital + ketamine | SEM | 12 | 51.0 | 3.0 | 12 | 32.5 | 5.0 |

| 55 | Zhao et al. [69] c | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | NSHD-2 | Post | (50 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital + ketamine | SEM | 12 | 46.5 | 6.0 | 12 | 25.5 | 4.5 |

| 56 | Zhao et al. [69] d | Mouse | M | 10–12 weeks | NSHD-2 | Post | (100 µg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 45 | LAD | 24 | R | Pentobarbital + ketamine | SEM | 12 | 46.5 | 6.0 | 17 | 24 | 5.0 |

| 57 | Zhu et al. [70] | Rat | M | 200–250 g | NaHS | Post | (14 µmol/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Urethane | STD | 12 | 37.4 | 3.3 | 12 | 19.0 | 2.0 |

| 58 | Zhuo et al. [71] | Rat | M | 250–300 g | NaHS | Pre | (14 µmol/kg/day) for 6 day prior to ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LAD | 48 | R | Chloral hydrate | STD | 8 | 32.7 | 3.7 | 8 | 22.2 | 5.9 |

Different letters refer to different studies and experimental groups within each included study (i.e. reference) and have been given according to how these studies or experimental group appear in the included each study following ascending order from A to Z

M male, F female, pre preconditioning, post postconditioning, LAD left anterior descending, LCA left coronary artery, SEM standard error of the mean, STD standard deviation of the mean

The main characteristics included: (1) study reference; (2) species; (3) gender; (4) age or weight; (5) H2S booster; (6) time of intervention; (7); conditioning protocol (pre- or postconditioning dose); (8) route of administration; (9) duration of index ischemia duration (min); (10) coronary artery occluded; (11) reperfusion duration (h); (12) recovery (R) or non-recovery (NR); (13) induction anaesthetic; (14) measure of variance; (15) control group sample size; (16) control group mean infarct size; (17) control group variance; (18) conditioning group sample size; (19) conditioning group mean infarct size; (20) conditioning group variance

Comparisons were divided into two main groups: preconditioning group (pre-H2S), where H2S booster was given any time before the onset of ischemia, and postconditioning group (post-H2S), where H2S booster was administrated during regional ischemia or at the commencement of reperfusion. The rationale for grouping the comparisons according to the time of intervention was due to the fact that these two windows of intervention arguably have different clinical applications. For instance, pre-H2S could be applied when the onset of ischemia is predictable (planned surgery), while post-H2S could be used as adjunctive therapy with reperfusion in STEMI patients.

Meta-analysis

For each independent comparison, the raw effect size (as a primary outcome) was calculated by subtracting the mean infarct size of the experimental group from the infarct size of the control group along with its correspondent 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We pooled raw effect sizes in each main group using random effect meta-analysis which takes into consideration between-comparison- and within-comparison variations and weights each comparison accordingly. Heterogeneity across different experimental protocols and models, within each main group, was quantified using I 2 statistics [27, 59]. All analyses were carried out using Review Manager (RevMan 5.3.5 Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

We also carried out subgroup analyses using univariate meta-regression based on pre-defined experimental factors (as a secondary outcome) which might potentially have an impact on the observed effect size of H2S and heterogeneity. The percentage of between-comparison variability explained by the variable of interest was evaluated by I 2 and adjusted R 2 statistics. The level of significance was adjusted to account for multiple comparisons using the Holm–Bonferroni method [26]. Furthermore, we also tested the robustness of our findings by conducting an additional stratified meta-analysis using standardised mean difference (SMD). SMD represented the mean difference in infarct size between control and H2S-treated groups divided by the pooled standard deviation of the mean.

Risk of bias

We also characterised the quality of study reporting for included studies using a predefined 20-point scoring scale based on the ARRIVE guidelines [34]. This was carried out by JSB and GFB independently and aimed to evaluate the rigour and transparency of included reports. Publication bias, in terms of effect size and degree of precision, was also evaluated independently by QGK and GFB by visual inspection of funnel plot of mean difference (MD) vs standard error of the mean (SD) for all included studies.

Results

Study selection process

Our initial search of the databases identified 8969 records (Fig. 1); 2938 duplicates were removed at this stage. 6031 reports were screened independently by QGK and JSB at the title level to check for relevancy to our study scope. 459 reports were considered relevant and screened at the abstract level to investigate if they met the inclusion criteria. As a result, 135 papers passed to the full-text review along with two studies which were identified through “snow-balling” at this stage. These articles were independently critiqued by JSB and QGK using our pre-defined, comprehensive critical appraisal tool. Finally, 32 papers were included in our analysis (Table 2), from which we included 58 controlled comparisons. We then divided the comparisons based on the time of intervention into pre-H2S (23 comparisons) and post-H2S (35 comparisons) groups.

Meta-analysis

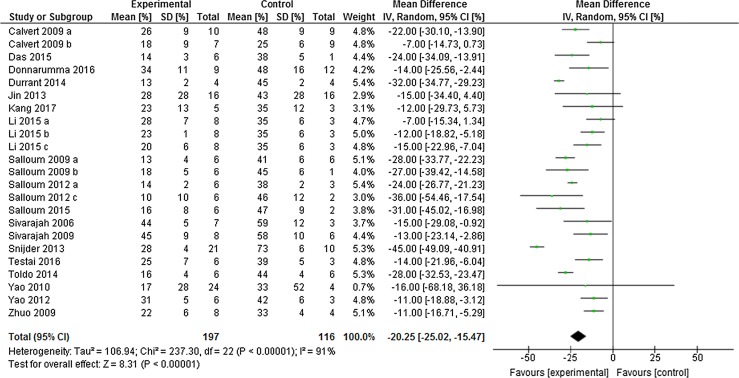

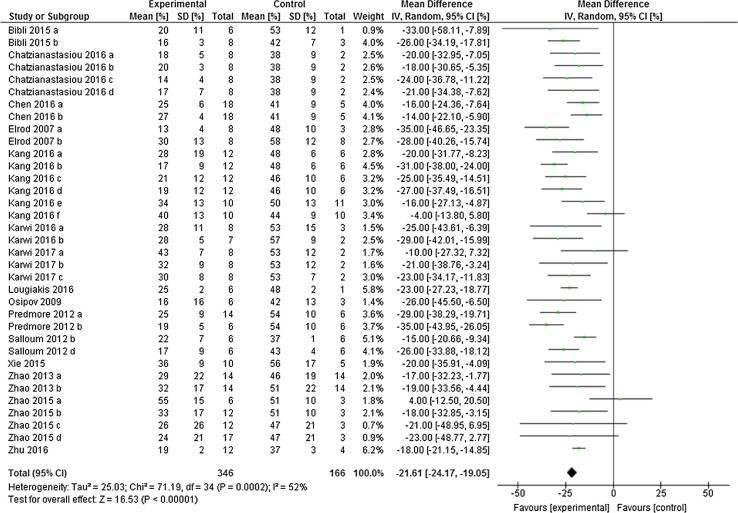

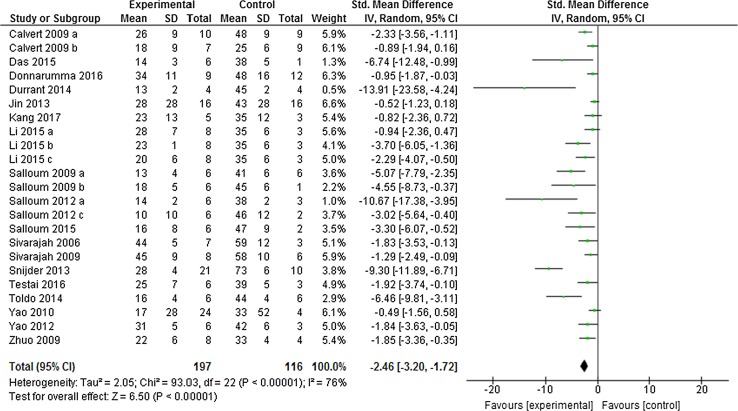

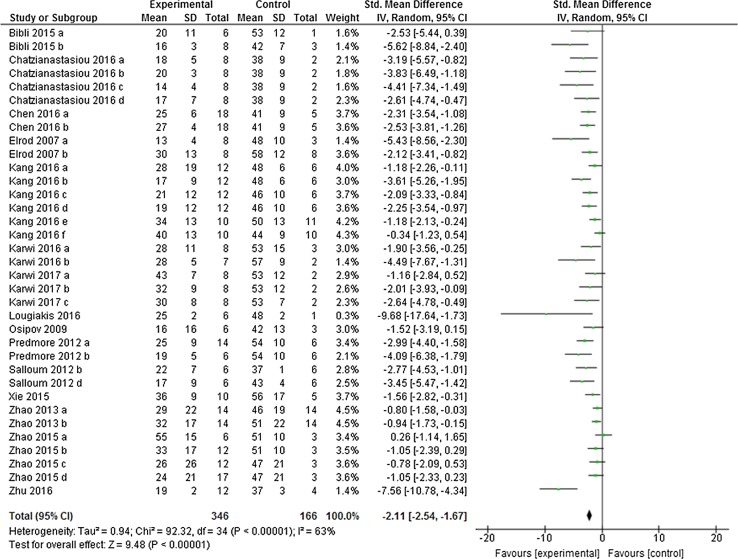

Preconditioning the heart using H2S boosters in vivo caused a significant limitation in infarct size of − 20.25% (95% CI − 25.02, − 15.47; Fig. 2) compared to control (p < 0.001, n = 23 comparisons). This meta-analysis included data from 116 control animals and 197 animals that received H2S boosters before ischemia. This overall effect size was accompanied by a high degree of heterogeneity measured using I 2 (91%, p < 0.001). In the post-H2S group, H2S also caused a significant infarct limitation of − 21.61% (95% CI − 24.17, − 19.05; Fig. 3), a result which was derived from 166 control animals and 346 H2S-treated animals (p < 0.001; n = 35 comparisons). Likewise, we also observed a high degree of heterogeneity in the post-H2S group (I 2 = 52%, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Preconditioning the heart with H2S in vivo. Forest plots of meta-analysis of preconditioning the heart with H2S boosters on myocardial infarction, pooled using random-effect meta-analysis. Controlled comparisons included data from 116 control animals and 197 treated animals

Fig. 3.

Postconditioning the heart with H2S in vivo. Forest plots of meta-analysis of postconditioning the heart with H2S boosters on myocardial infarction, pooled using random-effect meta-analysis. Controlled comparisons included data from 346 control animals and 166 treated animals

Sensitivity analysis

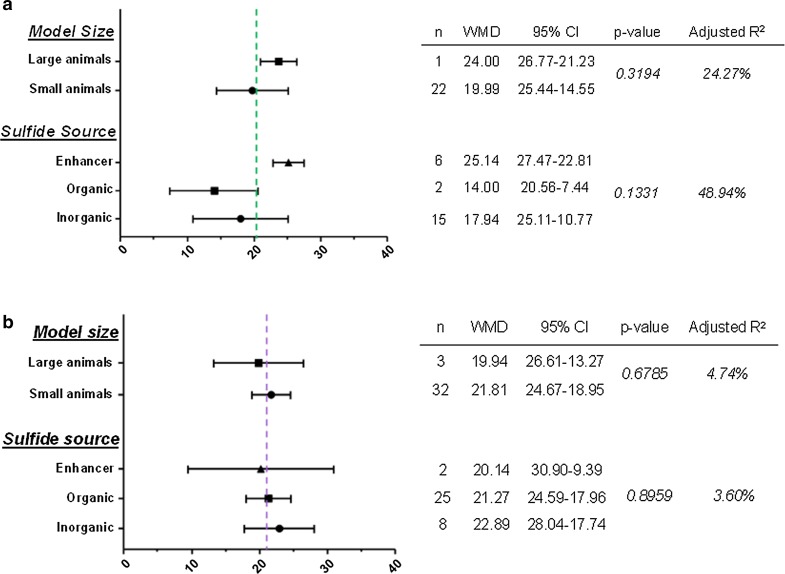

We also investigated the effect of two crucial experimental variants which might influence the observed effect size, namely the experimental animal size and the source of H2S. First, we divided each main group (i.e., pre-H2S and post-H2S) based on the size of the experimental model into small (mouse and rat) and large models (rabbit and pig). There was no significant difference in the overall effect size between the groups (pre-H2S: p = 0.3194, adjusted R 2 = 24.27% (Fig. 4a); post-H2S: p = 0.6785, adjusted R 2 = 4.74% (Fig. 4b). We also investigated whether any particular class of H2S boosters have an impact on the efficacy of observed infarct limitation. Therefore, we divided each main group based on the class of H2S booster into inorganic, organic and enhancer groups. Again, there was no significant difference in the overall effect size between these groups (pre-H2S: p = 0.1331, adjusted R 2 = 48.94% (Fig. 4a); post-H2S: p = 0.8959, adjusted R 2 = 3.60% (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Impact of experimental variables on the overall effect size of a preconditioning and b postconditioning with H2S. Subgroup stratification was used to obtain the weighted mean difference (WMD) along with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) followed by meta-regression to obtain the p value and avoid false-positive results. Studies that employed mice and rats were grouped as a “small animals” group, while those that used rabbit and pig were grouped as a “large animals” group. Studies were also grouped based on the source of H2S to “inorganic” which included sulfide salts and gas, “organic” and “enhancers” which included phosphodiesterase inhibitors. The dotted line indicates the weighted mean difference (WMD). None of the experimental variables had a significant effect on the observed effect size

We examined the robustness of our findings by re-running our meta-analysis using SMD instead of WMD. Interestingly, the results were similar in both cases and H2S, again, showed infarct limitation. H2S-induced preconditioning limited infarct size by − 2.46% (95% CI − 3.20, − 1.72, p < 0.001, Fig. 5) compared to control group with a similar degree of heterogeneity (I 2 = 76%). Likewise, postconditioning the heart with H2S boosters reduced myocardial infarction by − 2.11% (95% CI − 2.54, − 1.67, p < 0.001, Fig. 6) compared to the control heart with a similar degree of heterogeneity (I 2 = 63%).

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity test for the overall infarct limitation by pre-H2S in vivo. The overall effect size was calculated using standardised mean difference (SMD), pooled using random-effect meta-analysis. Controlled comparisons included data from 116 control animals and 197 treated animals

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity test for the overall infarct limitation by post-H2S in vivo. The overall effect size was calculated using standardised mean difference (SMD), pooled using random-effect meta-analysis. Controlled comparisons included data from 346 control animals and 166 treated animals

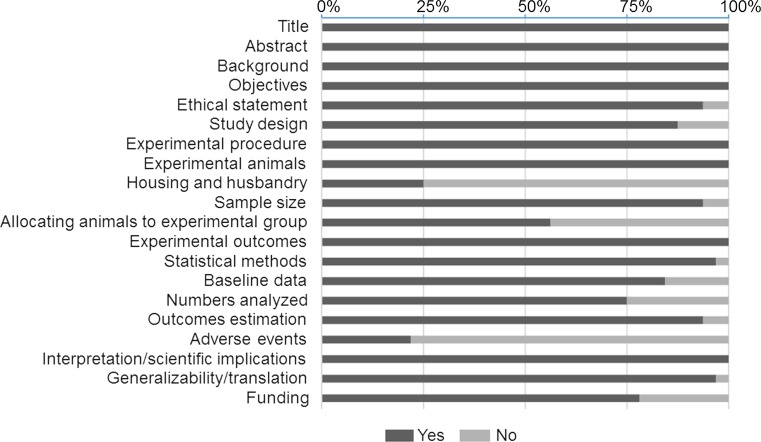

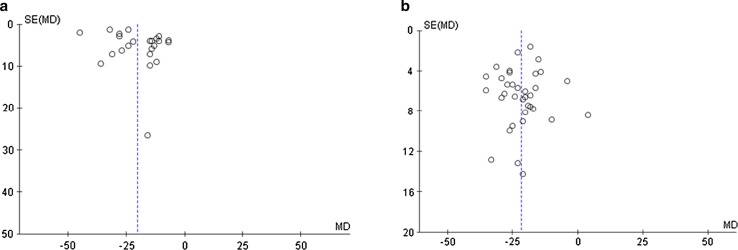

Risk of bias

We used a 20-point scoring scale to evaluate the quality of study reporting for included papers derived from ARRIVE guideline (Fig. 7). Included papers scored a median of 17 out of 20 with an interquartile range of 3. We also assessed the publication bias for the included papers by plotting the effect size (WMD) of each controlled comparison against its SD for pre-H2S and post-H2S groups using funnel plot (Fig. 8). Visual inspection of funnel plots showed that there might be underrepresentation of studies with negative or small effects. Furthermore, we also noticed that there were a few studies with moderate variance among included studies.

Fig. 7.

Study reporting quality assessment. The research quality of included studies were evaluated independently by two reviewers according to the quality of study reporting using our pre-defined 20-item quality scoring system. Data were reported as a percentage for each quality item

Fig. 8.

Evaluation of publication bias. A funnel plot showing the precision of the effect estimate in a preconditioning group and b postconditioning group. The dotted line indicates the weighted mean difference (MD). SE standard error

Discussion

The major findings of our systematic review and meta-analysis are that H2S has a consistent and robust infarct-limiting effect against MIRI in pre-clinical studies. This robust effect was comparable when H2S boosters were given before the onset of ischemia (preconditioning) or at the time of reperfusion (postconditioning) based on in vivo data from almost 900 animals. This cardioprotection also was independent from the animal size or the class of H2S booster.

The mechanism of H2S-induced conditioning-like phenomena is not fully understood yet, despite several signalling molecules and pathways have been suggested to play a role. However, we here discussed potential conditioning mechanism(s) of H2S based on the in vivo evidence included in this study. We took into consideration the causal and temporal consequences of conditioning events and used a structuring scheme previously proposed by Heusch [24]. This scheme is based on the general consensus that conditioning maneuver triggers a “stimulus” which in turn activates a “mediator” to transfer the cardioprotective signal to its “target”. In fact, H2S itself has been demonstrated to be a crucial “chemical stimulus” of ischemic pre- [67] and postconditioning [28] to elicit their infarct-limiting effect. Augmented level of H2S activates similar signalling molecules and pathways to act as mediators to transmit its cardioprotective signal to its target(s). These signalling pathways mainly involve activating the RISK pathway components in the first minutes of reperfusion [3, 9, 10, 13, 33, 38, 45, 49, 65]. Notably, the activity of some micro-RNAs, namely micro-RNA-21 [58] and mirco-RNA-1 [30], were also reported to serve as mediators of H2S-induced cardioprotection. The key target of H2S’s protection is the mitochondria, where the majority of salvage signalling pathways converges. Enhanced H2S level protects against myocardial infarction via preserving mitochondrial function [17], maintaining membrane integrity [17, 65], limiting mitochondrial ROS generation [32] and inhibiting the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP) [10, 32, 65]. Moreover, mitochondrial KATP channel is another target of H2S protection [54, 55, 57]. However, the question yet to be answered is how H2S triggers these signalling pathways to exert its infarct-limiting effect? It is highly unlikely that H2S activates the RISK pathway through a ligand/receptor-based mechanism as H2S is a gaseous molecule and not a ligand. The most plausible mechanism could be through inducing post-translation modifications (PTMs). Similar to nitrosylation, sulfhydration (or persulfidation) is a PTM induced by H2S which could modify the structure and eventually the function of several proteins and channels. Recently, it has been demonstrated that H2S activates PI3K/Akt signalling pathways through sulfhydrating phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) abrogating its inhibitory effect [62]. Furthermore, sulfhydration is demonstrated to modify the activity of mitochondrial KATP channel, another target of H2S [54, 55, 57], and ATP synthase (F1F0 ATP synthase/complex V) [39], the current proposed main component of PTP, which either is known to protect the mitochondria and eventually limit infarct size. Taken together, the role of sulfhydration in conditioning with H2S needs further investigation.

There are a number of important aspects which we observed in our review. Despite highly consistent overall effect size, we noticed a high degree of heterogeneity between the included studies. We conducted subgroup analyses to investigate whether some of the experimental variables which we predefined could influence the observed effect size and/or heterogeneity using meta-regression. Others have previously shown, applying the same approach, that experimental model size could have a significant impact on effect size and heterogeneity observed with meta-analysis. For example, Lim et al. [37] reported that cyclosporine-induced infarct limitation in rodent models was absent in a large model (swine) of MIRI in vivo. Noteworthily, this could potentially explain the neutral clinical data of cyclosporine treatment in STEMI patients [25]. However, Bromage et al. [6] recently showed that the infarct limitation by remote ischemic conditioning manoeuvre was consistent across in vivo studies, independently of the model size. Similarly, we previously demonstrated that enhanced level of nitric oxide (NO) in vivo, using different NO treatments, exerted infarct limitation independently of the model size across (22) pre-clinical studies [4]. Our subgroup analyses showed that model size (rodent vs. non-rodent model) did not have a significant effect on either effect size or heterogeneity of H2S treatments in both pre-H2S and post-H2S groups.

We also assessed whether using different H2S boosters as a pharmacological approach to enhance H2S level could behave differently in terms of infarct limitation and heterogeneity. There have been number of approaches employed to enhance H2S level in vivo to investigate its effect on myocardial infarction. Inorganic sulfide salts, namely NaHS and Na2S, were the first class of H2S boosters initially utilised to investigate the significance of enhancement H2S on myocardial infarction. However, they are impure salts that cause a sharp and short-lasting increase in H2S level in vivo which make them unreliable H2S boosters. Furthermore, off-target or even toxic effects are highly likely with the burst of H2S achieved using sulfide salts due to the fact that H2S has a narrow therapeutic window. More stable and controllable organic H2S donors have been designed to overcome this limitation and have demonstrated infarct-limiting effect in vivo [10, 33, 57, 68]. Utilising triphenylphosphonium scaffold approach to target the mitochondria, we and others have recently reported infarct limitation in vivo using AP39, a mitochondrial-targeting H2S donor [10, 32], which have a significant implication considering the central role of mitochondria in MIRI. In a similar context, we have recently reported that the limit of infarct reduction by different NO donors at reperfusion was consistently comparable [4]. Although there was a pattern of increased efficacy of postconditioning with H2S enhancers, there was significant difference in the efficacy of any of the H2S booster groups in terms of infarct limitation at the two times of intervention. To note, the number of studies that employed large animal models was less than those that used small animals. Furthermore, we also noticed that the cardioprotective dose of some H2S boosters could vary between different animal models. For instance, cardioprotective dose of GYY4137, a slow-releasing H2S donor, was (26.6 µmol/kg) in the mouse model [10], while it was 10 times more in rat [33]. There is no obvious reason why the cardioprotection dose of these boosters might vary. However, it has been shown that there is a certain degree of dependency of H2S on NO signalling to induce its cardioprotection. Arguably, this dependency on NO seems to be high in mouse [3] and partially fading as the animal size increase, such as in rat [33] until it becomes insignificant in large animals, such as rabbit [3]. Whether this hypothesis explains the variation in the cardioprotective dose of some H2S boosters requires further investigation.

We were also interested in assessing the impact of other experimental variables which are also important on the external validity of our findings. As our main aim in this review was to characterise the effect of H2S on infarct size across the preclinical studies, we, accordingly, excluded all studies which utilised animals with co-morbidities, co-medications and risk factors such as diabetes, heart failure, hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. Therefore, insufficient number of studies in this review rendered these analyses not applicable. Nevertheless, in vivo preclinical studies utilised animals with co-morbidities which were identified in our literature search are summarised in (Table 3). This table is very helpful and has a considerable value for the field of cardioprotection with H2S as a starting point for future investigations characterising the impact of co-morbidities on H2S protection. Co-morbidities and risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease are important determinants of the efficacy of any cardioprotective therapy and this has recently been discussed in some position papers by others [8, 20, 21, 23]. There is a significant contrast in the biological milieu between the experimental animals and the patients. The majority of the cardioprotective interventions that have been tested in a “reductionist model” employing young and healthy animals, arguably to effectively control the experimental conditions [50]. However, the vast majority of patients recruited in the randomised clinical trials have co-morbidities and/or risk factors including diabetes, aging, hyperlipidemia and hypertension. These co-morbidities and risk factors are shown to modify the efficacy of several cardioprotective interventions [20, 22]. In addition, the potential impact of background medications on the examined efficacy of cardioprotective therapies is often neglected in the pre-clinical studies, despite the fact that most of the recruited patients are on standard medications. Similarly, current standard care could substantially alter the potency of cardioprotective therapies via either blocking the signalling pathway or elevating the threshold which is needed to produce the cardioprotection [22, 47]. Therefore, clinical translation could be considerably enhanced through conducting future preclinical studies on animals with co-morbidities and from a background of standard medications.

Table 3.

Summary of pre-clinical studies investigated infarct-limiting effect of H2S using animals with co-morbidities

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gao et al. [19] | Streptozocin-induced diabetic rat | M | 250–30 g | NaHS | Pre | (14 µmol/kg) daily for 7 days before ischemia | i.p. | 30 | LAD | 2 | NR | Chloral hydrate | STD | 6 | 44.0 | 7.2 | 6 | 31.2 | 4.7 |

| 2 | Lambert et al. [35] a | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (0.05 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 4 | NR | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 7 | 74.2 | 3.1 | 8 | 62.0 | 3.0 |

| 3 | Lambert et al. [35] b | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (0.1 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 4 | NR | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 7 | 74.2 | 3.1 | 7 | 56.3 | 3.4 |

| 4 | Lambert et al. [35] c | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (0.5 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 4 | NR | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 7 | 74.2 | 3.1 | 5 | 60.1 | 5.0 |

| 5 | Lambert et al. [35] d | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (1 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 4 | NR | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 7 | 74.2 | 3.1 | 5 | 68.2 | 3.2 |

| 6 | Lambert et al. [35] e | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (0.1 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 24 | R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 10 | 68.4 | 1.8 | 10 | 53.9 | 2.0 |

| 7 | Lambert et al. [35] f | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Post | (0.1 mg/kg) at reperfusion | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 4 | N R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 6 | 67.4 | 4.6 | 6 | 55.0 | 2.4 |

| 8 | Peake et al. [46] a | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Pre | (0.1 mg/kg) the day before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 2 | N R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 8 | 73.5 | 1.8 | 8 | 60.0 | 1.5 |

| 9 | Peake et al. [46] b | Diabetic (db/db) mouse | M | 12 weeks | Na2S | Pre | (0.1 mg/kg) daily for 7 days before ischemia | i.v. | 30 | LCA | 2 | N R | Ketamine + pentobarbital | SEM | 8 | 73.5 | 1.8 | 10 | 46.5 | 2.4 |

Different letters refer to different studies and experimental groups within each included study (i.e. reference) and have been given according to how these studies or experimental group appear in the included each study following ascending order from A to Z

M male, F female, pre preconditioning, post postconditioning, LAD left anterior descending, LCA left coronary artery, SEM standard error of the mean, STD standard deviation of the mean

The main characteristics included: (1) study reference; (2) species; (3) gender; (4) age or weight; (5) H2S booster; (6) time of intervention; (7); conditioning protocol (pre- or postconditioning dose); (8) route of administration; (9) duration of index ischemia duration (min); (10) coronary artery occluded; (11) reperfusion duration (h); (12) recovery (R) or non-recovery (NR); (13) induction anaesthetic; (14) measure of variance; (15) control group sample size; (16) control group mean infarct size; (17) control group variance; (18) conditioning group sample size; (19) conditioning group mean infarct size; (20) conditioning group variance

Another important experimental variable is gender, taking into consideration the cardioprotection of oestrogen which is mainly mediated by triggering the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway [42], a common signalling pathway with H2S [33]. However, only 9% of included studies employed mixed gender. Another dimension to the reductionist model often employed in the pre-clinical studies is the use of a single therapy which is too simplistic and underestimates the clinical complexity. In the view of the current failure in clinical translation, the use of two or more drugs in what is often called “combination therapy” has been suggested as an alternative approach [22]. Especially, some combination treatments have shown promising benefits in vivo [64] and in human [16]. With the current advanced feasibility in designing H2S boosters which target different cellular compartments, it is tempting to suggest that combination therapy of different H2S boosters could potentially enhance the efficacy of H2S-induced cardioprotection. Especially, different H2S boosters signal through different protective mechanisms and could potentially have additive infarct-limiting effect to each other which maximise the beneficial effect [1, 32]. Despite this very tempting idea along with very encouraging experimental data, this concept has not been investigated yet and needs to be conducted in well-designed studies. We have listed H2S boosters which we think have potential clinical translatability along with proposed mechanism(s) of cardioprotection (Table 4). This table would have a great value for the field of cardioprotection and very helpful to test the concept of combination therapy in future investigations.

Table 4.

List of H2S boosters with potential clinical translatability and proposed mechanism of infarct limitation

| H2S booster | Efficacy to limit infarct size (%) | Proposed mechanism(s) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GYY4137 | 31–51 | Activates PI3K/Akt/eNOS/GSK-3β signalling pathway | [10, 30, 32] |

| 2 | Thiovalin | 62 | Triggers eNOS/NO signalling pathway | [10] |

| 3 | AP39 | 43–56 | Signals independently of cytosolic signalling pathways Limits mitochondrial ROS generation Inhibits Ca2+-induced PTP opening in a cyclophilin-D-independent manner |

[10, 31] |

| 4 | hs-MB | 39 | Unknown | [11] |

| 5 | Ad.PKGIα | 62 | Activates PKG | [12] |

| 6 | Zofenopril | 29 | Activates eNOS and increases plasma NO level Upregulates the expression of antioxidant enzymes (thioredoxin-1, glutathione peroxidase-1 and sodium dismutase-1) |

[13] |

| 7 | JK-1 | 43–64 | Unknown | [30] |

| 8 | JK-2 | 55 | Unknown | [30] |

| 9 | 4-OH-TBZ | 48 | Unknown | [36] |

| 10 | DATS | 65 | Activates eNOS/NO signalling pathway | [46] |

| 11 | Tadalafil | 68 | Activates PKG | [48] |

| 12 | Cinaciguat | 62–77 | Increases PKG activity and CSE expression | [49] |

| 13 | Beetroot juice | 66 | Unknown | [50] |

| 14 | 4CPI | 36 | Activates mitochondrial KATP channel | [54] |

| 15 | ADT | 36 | Activates AMPK and autophagic flux | [60] |

| 16 | 8a | 38 | Unknown | [65] |

| 17 | 8I | 38 | Unknown | [65] |

| 18 | NSHD-1 | 36 | Unknown | [66] |

| 19 | NSHD-2 | 45 | Unknown | [66] |

We also evaluated the internal validity of included studies including the quality of study reporting and publication bias and how these factors could have an impact on the observed results. The lack of full and comprehensive description of the methodological approach and study design could result in an overestimated effect size. By subjecting the included reports to our reporting quality assessment, included studies generally scored highly which is strengthening the validity of our study and it is due to our stringent inclusion criteria. Nevertheless, there was particularly poor reporting in a number of aspects including reporting any adverse effects (28%), a main determinant in any drug development. Reporting of sample size calculation was also poor (43%) which raises some important question regarding whether the study was sufficiently powered before commencing the experiments or allowed to continue until certain number of animals per group was achieved. Insufficient adherence to good quality research indicators could inevitably lead to false-positive results and overestimation of the effect size. As a consequence, this might subsequently lead to further testing of a particular treatment in clinical trial, as a logical consequence, which would be unethical and unnecessary. Furthermore, low standard study reporting makes it difficult to ascertain whether the study was conducted according to high-quality research standards which eventually assuring that the data are valid. Noteworthily, failing to report a good quality research could possibility account for the observed heterogeneity in this meta-analysis. Nevertheless, the effect size by H2S was consistent and robust despite the observed high heterogeneity which is reassuring.

We also investigated the publication bias within the included studies using funnel plot. The visual examination and the distribution of the effect size along with the precision of the measurement suggested that there might be an underrepresentation of studies with neutral or negative effect as well as studies with moderate precision in our analysis. However, it needs to be stressed here that studies with neutral or negative data are often not given priority, if at all, to be submitted for publication by the majority of the research groups especially that it is highly likely that they will be rejected at the peer review stage.

Limitation

This review has included all studies which met our stringent inclusion criteria. However, we acknowledge that we were limited by not including papers which are not published in English language for a time and financial limitations. We also had to exclude studies with missing data or those which failed our critical appraisal to enhance the validity of this meta-analysis. Furthermore, we could not identify any particular variable behind the high degree of heterogeneity using our pre-defined experimental variables. In addition, we also acknowledge that the ARRIVE guideline was launched in June 2010 in the UK, while significant number of studies included in our analysis were either published before this date or conducted outside the UK.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis shows a robust and highly reproducible infarct-limiting effect of H2S against MIRI in pre-clinical studies. This robust effect was similar when H2S was administrated before the onset of regional ischemia or at reperfusion despite the observed high heterogeneity which is reassuring. The current feasibility of designing stable and controllable H2S boosters and selectively targeting specific cellular compartments offer a unique opportunity to use a combination therapy of different H2S boosters, which signal through different cardioprotective mechanisms, as an adjunct to standard reperfusion protocol. The focus of future investigations should be on characterising the observed infarct-sparing effect of H2S in large animal with co-morbidities, such as diabetes and age, and from background of the current standard polypharmacy in a well-designed preclinical studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

QGK acknowledges the generous support of University of Diyala and the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

Author contributions

QGK, JSB and GFB conceived and designed the study. QGK and JSB were the primary reviewers, while GFB was the secondary reviewer during literature search and data collection. QGK prepared the manuscript which was finalised and approved for submission by all authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00395-017-0664-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Andreadou I, Iliodromitis EK, Rassaf T, Schulz R, Papapetropoulos A, Ferdinandy P. The role of gasotransmitters NO, H2S and CO in myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection by preconditioning, postconditioning and remote conditioning. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:1587–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell RM, Botker HE, Carr RD, Davidson SM, Downey JM, Dutka DP, Heusch G, Ibanez B, Macallister R, Stoppe C, Ovize M, Redington A, Walker JM, Yellon DM. 9th hatter biannual meeting: position document on ischaemia/reperfusion injury, conditioning and the ten commandments of cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:41. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0558-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibli SI, Andreadou I, Chatzianastasiou A, Tzimas C, Sanoudou D, Kranias E, Brouckaert P, Coletta C, Szabo C, Kremastinos DT, Iliodromitis EK, Papapetropoulos A. Cardioprotection by H2S engages a cGMP-dependent protein kinase G/phospholamban pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;106:432–442. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bice JS, Jones BR, Chamberlain GR, Baxter GF. Nitric oxide treatments as adjuncts to reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review of experimental and clinical studies. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:23. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0540-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos EM, van Goor H, Joles JA, Whiteman M, Leuvenink HG. Hydrogen sulfide: physiological properties and therapeutic potential in ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:1479–1493. doi: 10.1111/bph.12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromage DI, Pickard JM, Rossello X, Ziff OJ, Burke N, Yellon DM, Davidson SM. Remote ischaemic conditioning reduces infarct size in animal in vivo models of ischaemia–reperfusion injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:288–297. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulluck H, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Reducing myocardial infarct size: challenges and future opportunities. Heart. 2016;102:341–348. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrera-Fuentes HA, Alba-Alba C, Aragones J, Bernhagen J, Boisvert WA, Botker HE, Cesarman-Maus G, Fleming I, Garcia-Dorado D, Lecour S, Liehn E, Marber MS, Marina N, Mayr M, Perez-Mendez O, Miura T, Ruiz-Meana M, Salinas-Estefanon EM, Ong SB, Schnittler HJ, Sanchez-Vega JT, Sumoza-Toledo A, Vogel CW, Yarullina D, Yellon DM, Preissner KT, Hausenloy DJ. Meeting report from the 2nd international symposium on new frontiers in cardiovascular research. protecting the cardiovascular system from ischemia: between bench and bedside. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:7. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0527-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Pattillo CB, Kevil CG, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:365–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatzianastasiou A, Bibli SI, Andreadou I, Efentakis P, Kaludercic N, Wood ME, Whiteman M, Di Lisa F, Daiber A, Manolopoulos VG, Szabo C, Papapetropoulos A. Cardioprotection by H2S donors: nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;106:432–442. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.235119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen GB, Yang L, Zhong LT, Kutty S, Wang YG, Cui K, Xiu JC, Cao SP, Huang QB, Liao WJ, Liao YL, Wu JF, Zhang WZ, Bin JP. Delivery of hydrogen sulfide by ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction attenuates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30643-30456. doi: 10.1038/srep30643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das A, Samidurai A, Hoke NN, Kukreja RC, Salloum FN. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the cardioprotective effects of gene therapy with PKG-I alpha. Basic Res Cardiol. 2015;110:42–54. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0500-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnarumma E, Ali MJ, Rushing AM, Scarborough AL, Bradley JM, Organ CL, Islam KN, Polhemus DJ, Evangelista S, Cirino G, Jenkins JS, Patel RAG, Lefer DJ, Goodchild TT. Zofenopril protects against myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury by increasing nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide bioavailability. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003531–e003549. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnarumma E, Trivedi RK, Lefer DJ. Protective actions of H2S in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Compr Physiol. 2017;7:583–602. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durrant D, Mauro AG, Raleigh JV, Das A, He J, Nguyen K, Toldo S, Abbate A, Salloum FN. MAVS mediates protection against myocardial ischemic injury with hydrogen sulfide. Circ Res. 2014;115:E87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eitel I, Stiermaier T, Rommel KP, Fuernau G, Sandri M, Mangner N, Linke A, Erbs S, Lurz P, Boudriot E, Mende M, Desch S, Schuler G, Thiele H. Cardioprotection by combined intrahospital remote ischaemic preconditioning and postconditioning in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the randomized LIPSIA CONDITIONING trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3049–3057. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, Jiao X, Scalia R, Kiss L, Szabo C, Kimura H, Chow CW, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferdinandy P, Hausenloy DJ, Heusch G, Baxter GF, Schulz R. Interaction of risk factors, comorbidities, and comedications with ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection by preconditioning, postconditioning, and remote conditioning. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66:1142–1174. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Y, Yao XY, Zhang YN, Li WM, Kang K, Sun L, Sun XY. The protective role of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion-induced injury in diabetic rats. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausenloy DJ, Barrabes JA, Botker HE, Davidson SM, Di Lisa F, Downey J, Engstrom T, Ferdinandy P, Carbrera-Fuentes HA, Heusch G, Ibanez B, Iliodromitis EK, Inserte J, Jennings R, Kalia N, Kharbanda R, Lecour S, Marber M, Miura T, Ovize M, Perez-Pinzon MA, Piper HM, Przyklenk K, Schmidt MR, Redington A, Ruiz-Meana M, Vilahur G, Vinten-Johansen J, Yellon DM, Garcia-Dorado D. Ischaemic conditioning and targeting reperfusion injury: a 30 year voyage of discovery. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:70–94. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0588-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hausenloy DJ, Botker HE, Engstrom T, Erlinge D, Heusch G, Ibanez B, Kloner RA, Ovize M, Yellon DM, Garcia-Dorado D. Targeting reperfusion injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: trials and tribulations. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:935–941. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hausenloy DJ, Garcia-Dorado D, Bøtker HE, Davidson SM, Downey J, Engel FB, Jennings R, Lecour S, Leor J, Madonna R, Ovize M, Perrino C, Prunier F, Schulz R, Sluijter JPG, Van Laake LW, Vinten-Johansen J, Yellon DM, Ytrehus K, Heusch G, Ferdinandy P. Novel targets and future strategies for acute cardioprotection: position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:564–585. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heusch G. Critical issues for the translation of cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2017;120:1477–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heusch G. Molecular basis of cardioprotection: signal transduction in ischemic pre-, post-, and remote conditioning. Circ Res. 2015;116:674–699. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heusch G, Gersh BJ. The pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction and strategies of protection beyond reperfusion: a continual challenge. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:774–784. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hooijmans CR, IntHout J, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Rovers MM. Meta-analyses of animal studies: an introduction of a valuable instrument to further improve healthcare. ILAR J. 2014;55:418–426. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilu042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang YE, Tang ZH, Xie W, Shen XT, Liu MH, Peng XP, Zhao ZZ, Nie DB, Liu LS, Jiang ZS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide mediates the cardioprotection induced by ischemic postconditioning in the early reperfusion phase. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:1117–1123. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin HF, Wang Y, Wang XB, Sun Y, Tang CS, Du JB. Sulfur dioxide preconditioning increases antioxidative capacity in rat with myocardial ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury. Nitric Oxide. 2013;32:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang B, Li W, Xi W, Yi Y, Ciren Y, Shen H, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Xiao J, Wang Z. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes against apoptosis in ischemia/reperfusion through mir-1-regulated histone deacetylase 4 pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:10–21. doi: 10.1159/000455816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang JM, Li Z, Organ CL, Park CM, Yang CT, Pacheco A, Wang DF, Lefer DJ, Xian M. pH-controlled hydrogen sulfide release for myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6336–6339. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karwi QG, Bornbaum J, Boengler K, Torregrossa R, Whiteman M, Wood ME, Schulz R, Baxter GF. AP39, a mitochondria-targeting hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donor, protects against myocardial reperfusion injury independently of salvage kinase signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:287–301. doi: 10.1111/bph.13688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karwi QG, Whiteman M, Wood ME, Torregrossa R, Baxter GF. Pharmacological postconditioning against myocardial infarction with a slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor, GYY4137. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG, Group NCRRGW Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert JP, Nicholson CK, Amin H, Amin S, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide provides cardioprotection against myocardial/ischemia reperfusion injury in the diabetic state through the activation of the RISK pathway. Med Gas Res. 2014;4:20–31. doi: 10.1186/s13618-014-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li CY, Hu M, Wang Y, Lu H, Deng J, Yan XH. Hydrogen sulfide preconditioning protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through inhibition of endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:7740–7751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim WY, Messow CM, Berry C. Cyclosporin variably and inconsistently reduces infarct size in experimental models of reperfused myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:2034–2043. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lougiakis N, Papapetropoulos A, Gikas E, Toumpas S, Efentakis P, Wedmann R, Zoga A, Zhou ZM, Iliodromitis EK, Skaltsounis AL, Filipovic MR, Pouli N, Marakos P, Andreadou I. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel adenine-hydrogen sulfide slow release hybrids designed as multitarget cardioprotective agents. J Med Chem. 2016;59:1776–1790. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Modis K, Ju Y, Ahmad A, Untereiner AA, Altaany Z, Wu L, Szabo C, Wang R. S-sulfhydration of ATP synthase by hydrogen sulfide stimulates mitochondrial bioenergetics. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy E, Ardehali H, Balaban RS, DiLisa F, Dorn GW, 2nd, Kitsis RN, Otsu K, Ping P, Rizzuto R, Sack MN, Wallace D, Youle RJ, American Heart Association Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences CoCC, Council on Functional G, Translational B Mitochondrial function, biology, and role in disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Res. 2016;118:1960–1991. doi: 10.1161/RES.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Gender-based differences in mechanisms of protection in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Connor D, Green S, Higgins JP. Defining the review question and developing criteria for including studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2008. pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osipov RM, Robich MP, Feng J, Liu Y, Clements RT, Glazer HP, Sodha NR, Szabo C, Bianchi C, Sellke FW. Effect of hydrogen sulfide in a porcine model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion: comparison of different administration regimens and characterization of the cellular mechanisms of protection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54:287–297. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181b2b72b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peake BF, Nicholson CK, Lambert JP, Hood RL, Amin H, Amin S, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide preconditions the db/db diabetic mouse heart against ischemia–reperfusion injury by activating Nrf2 signaling in an Erk-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1215–H1224. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00796.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pocock SJ, Gersh BJ. Do current clinical trials meet society’s needs? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1615–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polhemus DJ, Li Z, Pattillo CB, Gojon G, Sr, Gojon G, Jr, Giordano T, Krum H. A novel hydrogen sulfide prodrug, SG1002, promotes hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide bioavailability in heart failure patients. Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;33:216–226. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Predmore BL, Kondo K, Bhushan S, Zlatopolsky MA, King AL, Aragon JP, Grinsfelder DB, Condit ME, Lefer DJ. The polysulfide diallyl trisulfide protects the ischemic myocardium by preservation of endogenous hydrogen sulfide and increasing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2410–H2418. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00044.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossello X, Yellon DM. A critical review on the translational journey of cardioprotective therapies! Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salloum FN, Chau VQ, Hoke NN, Abbate A, Varma A, Ockaili RA, Toldo S, Kukreja RC. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, tadalafil, protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through protein-kinase G-dependent generation of hydrogen sulfide. Circ. 2009;120:S31–S36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salloum FN, Das A, Samidurai A, Hoke NN, Chau VQ, Ockaili RA, Stasch JP, Kukreja RC. Cinaciguat, a novel activator of soluble guanylate cyclase, protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury: role of hydrogen sulfide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1347–H1354. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00544.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salloum FN, Sturz GR, Yin C, Rehman S, Hoke NN, Kukreja RC, Xi L. Beetroot juice reduces infarct size and improves cardiac function following ischemia–reperfusion injury: possible involvement of endogenous H2S. Exp Biol Med. 2015;240:669–681. doi: 10.1177/1535370214558024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sivarajah A, Collino M, Yasin M, Benetti E, Gallicchio M, Mazzon E, Cuzzocrea S, Fantozzi R, Thiemermann C. Anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects of hydrogen sulfide in a rat model of regional myocardial I/R. Shock. 2009;31:267–274. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318180ff89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sivarajah A, McDonald M, Thiemermann C. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to the cardioprotective effects of pre-conditioning with endotoxin, but not ischemia, in the rat. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snijder PM, de Boer RA, Bos EM, van den Born JC, Ruifrok WPT, Vreeswijk-Baudoin I, van Dijk M, Hillebrands JL, Leuvenink HGD, van Goor H. Gaseous hydrogen sulfide protects against myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in mice partially independent from hypometabolism. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63291–e63302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Testai L, Marino A, Piano I, Brancaleone V, Tomita K, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Martelli A, Citi V, Breschi MC, Levi R, Gargini C, Bucci M, Cirino G, Ghelardini C, Calderone V. The novel H2S-donor 4-carboxyphenyl isothiocyanate promotes cardioprotective effects against ischemia/reperfusion injury through activation of mitoKATP channels and reduction of oxidative stress. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toldo S, Das A, Mezzaroma E, Chau VQ, Marchetti C, Durrant D, Samidurai A, Van Tassell BW, Yin C, Ockaili RA, Vigneshwar N, Mukhopadhyay ND, Kukreja RC, Abbate A, Salloum FN. Induction of microRNA-21 with exogenous hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemic and inflammatory injury in mice. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:311–320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vesterinen HM, Sena ES, Egan KJ, Hirst TC, Churolov L, Currie GL, Antonic A, Howells DW, Macleod MR. Meta-analysis of data from animal studies: a practical guide. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;221:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wallace JL, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:329–345. doi: 10.1038/nrd4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warenycia MW, Goodwin LR, Benishin CG, Reiffenstein RJ, Francom DM, Taylor JD, Dieken FP. Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Demonstration of selective uptake of sulfide by the brainstem by measurement of brain sulfide levels. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:973–981. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu D, Li M, Tian W, Wang S, Cui L, Li H, Wang H, Ji A, Li Y. Hydrogen sulfide acts as a double-edged sword in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells through EGFR/ERK/MMP-2 and PTEN/AKT signaling pathways. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5134–5148. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05457-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie H, Xu Q, Jia J, Ao G, Sun Y, Hu L, Alkayed NJ, Wang C, Cheng J. Hydrogen sulfide protects against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury by activating AMP-activated protein kinase to restore autophagic flux. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang XM, Cui L, Alhammouri A, Downey JM, Cohen MV. Triple therapy greatly increases myocardial salvage during ischemia/reperfusion in the in situ rat heart. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2013;27:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s10557-013-6474-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao LL, Huang XW, Wang YG, Cao YX, Zhang CC, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis by preventing GSK-3beta-dependent opening of mPTP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1310–H1319. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00339.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yao X, Tan G, He C, Gao Y, Pan S, Jiang H, Zhang Y, Sun X. Hydrogen sulfide protects cardiomyocytes from myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury by enhancing phosphorylation of apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;226:275–285. doi: 10.1620/tjem.226.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yong QC, Lee SW, Foo CS, Neo KL, Chen X, Bian JS. Endogenous hydrogen sulphide mediates the cardioprotection induced by ischemic postconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1330–H1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00244.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao Y, Bhushan S, Yang CT, Otsuka H, Stein JD, Pacheco A, Peng B, Devarie-Baez NO, Aguilar HC, Lefer DJ, Xian M. Controllable hydrogen sulfide donors and their activity against myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1283–1290. doi: 10.1021/cb400090d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao Y, Yang CT, Organ C, Li Z, Bhushan S, Otsuka H, Pacheco A, Kang JM, Aguilar HC, Lefer DJ, Xian M. Design, synthesis, and cardioprotective effects of n-mercapto-based hydrogen sulfide donors. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7501–7511. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu XY, Wang Y, Ding YL, Deng J, Yan XH. Cardioprotection by H2S postconditioning engages the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:17529–17538. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhuo Y, Chen PF, Zhang AZ, Zhong H, Chen CQ, Zhu YZ. Cardioprotective effect of hydrogen sulfide in ischemic reperfusion experimental rats and its influence on expression of survivin gene. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1406–1410. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.