Abstract

We reviewed the literature on transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) used as a therapy for overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, with a particular focus on: stimulation site, stimuli parameters, neural structures thought to be targeted, and the clinical and urodynamic outcomes achieved. The majority of studies used sacral or tibial nerve stimulation. The literature suggests that, whilst TENS therapy may have neuromodulation effects, patient are unlikely to benefit to a significant extent from a single application of TENS and indeed clear benefits from acute studies have not been reported. In long-term studies there were differences in the descriptions of stimulation intensity, strategy of the therapy, and positioning of the electrodes, as well as in the various symptoms and pathology of the patients. Additionally, most studies were uncontrolled and hence did not evaluate the placebo effect. Little is known about the underlying mechanism by which these therapies work and therefore exactly which structures need to be stimulated, and with what parameters. There is promising evidence for the efficacy of a transcutaneous stimulation approach, but adequate standardisation of stimulation criteria and outcome measures will be necessary to define the best way to administer this therapy and document its efficacy.

Keywords: Overactive bladder, Posterior tibial nerve stimulation, Sites of stimulation, Sacral stimulation, Sham stimulation methodology, Surface electrodes, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

1. Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms syndrome is a well-recognised set of symptoms which patient experience during the storage phase of the micturition cycle. It is characterised by urgency (a sudden compelling desire to pass urine which is difficult to defer) which, in almost all patients, is accompanied by increased frequency and nocturia and, particularly in female patients, by urgency incontinence [1]. Around one third of female patients are severely bothered by urinary incontinence [2].

Electrical stimulation has been used over several decades in the treatment of various lower urinary tract dysfunctions. The well-established Finetech-Bridley sacral anterior root stimulator [3], an implanted electrical sacral roots (S2–S4) stimulator to aid emptying the bladder, formed a precursor to today's widely used sacral neuromodulation techniques [4], [5]. The S2–S4 nerve roots provide the principle motor supply to the bladder. Specifically the S3 root mainly innervates the detrusor muscle and is the main target of sacral neuromodulation.

Another important and well-established stimulation site is that of the posterior tibial nerve (PTN). The PTN is a mixed nerve containing L5–S3 fibres, originating again from the same spinal segments as the parasympathetic innervations to the bladder (S2–S4). The Stoller afferent nerve stimulator (SANS) was introduced, to stimulate PTN using a 34-gauge needle electrode inserted into the same place as used in electro acupuncture (the so-called SP6 point), with a surface electrode placed behind the medial malleolus [6]. Currently a commercial device (Urgent-PC, Uroplasty, Inc., Minnetonka, USA) uses this technique. Usually 12 sessions of the percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), at weekly intervals, are used and a large randomized placebo controlled trial showed significant improvement in overall OAB symptoms (60/110) compare to sham (23/110) [7]. It was shown that PTNS responders can continue to benefit from the therapy over 12 months [8]. The exact mechanism of PTNS remains unclear and further multidisciplinary studies are needed to clarify this.

For the purpose of this review we are going to consider only non-invasive techniques, defined as “a procedure which does not involve introduction of an instrument into the body”. Further, we also define transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) as a technique where the electrical stimuli are passed through the intact skin.

The primary reason to focus on this modality is that it has a number of practical advantages in its delivery. The method is completely non-invasive, with surface electrodes connected to a battery operated low cost stimulator and applied to an appropriate site of the body. The stimulators are simple to operate with non-expensive, usually hydrogel based, electrodes and batteries being the only on-going treatment cost. TENS treatment itself should not require regular patient visits at clinics and usually is self-administered at home, which is convenient for the patient. In general there are minimal or no side effects from TENS, although sometimes redness or skin irritation may occur around the electrodes which resolves once the stimulation session is finished. TENS has also been used for several decades for pain control. The use of TENS in the treatment of OAB and lower urinary tract diseases is less well-established.

Other minimally invasive electrical stimulation techniques such as: anal, vaginal stimulation plugs [9], [10]; percutaneous stimulation (needle is inserted near a targeted nerve); or implanted stimulation devices are beyond the scope of this review [4], [5]. In particular plugs are often rejected by the patient because of embarrassment and a sense of unclean liness [11].

The dorsal genital nerve has been used as another site of stimulation [10] using surface electrodes to deliver the stimuli. However, as this review is focused on techniques that are convenient for patients we have not reviewed in detail these studies.

2. Methods

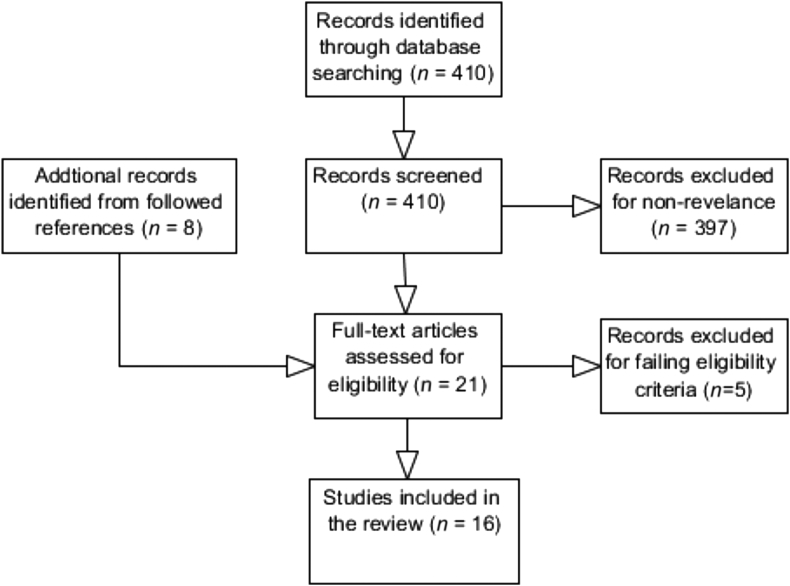

We searched the electronic database PubMed from inception until December 2013. Search terms used were “urge incontinence”, “urgency”, “overactive bladder”, “urinary incontinence” or “detrusor instability” in combination with “electrical stimulation”, “TENS”, “transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation”, “nerve stimulation”, “surface neuromodulation”, “non-invasive stimulation”, “trial” or “study”. In addition, we followed citations from the primary references to relevant articles which the database could not locate. Exclusion criteria were: studies which were not in English; studies of faecal incontinence treatment; those involving children, those studying animal models; those involving percutaneous electrical stimulation, anal stimulation, vaginal/penile stimulation or implanted devices or those not primarily focused on storage symptoms. A flow diagram of the selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the paper selection process.

3. Results

The primary search identified 410 articles. Using the defined exclusion criteria we reviewed in detail 16 articles. We have not specifically reviewed studies with a primary focus on interstitial cystitis or voiding dysfunction although these are mentioned where relevant.

3.1. Sacral stimulation

In 1996 Hasan et al. [12] compared S3 neuromodulation using implanted devices with TENS applied over the perianal region (S2–S3 dermatomes). Improvement in more than 50% of idiopathic detrusor overactivity patients suggested the potential of using TENS at a sacral site.

In a study by Walsh et al. [13] 1 week of continuous stimulation for 12 h per day at S3 dermatomes significantly improved both frequency and nocturia. However only 3/32 patients continued with the therapy, and only on an intermittent basis, during up to 6 months of follow-up. The authors did not evaluate whether the patients found using TENS for 12 h a day was inconvenient and potentially may lead for discontinuing the therapy.

Following this study, an urodynamically assessed group of 33 patients with detrusor overactivity and symptoms of OAB reported similar effects for self-administered stimulation over the sacral site twice a day when compared to oxybutynin in a 14-weeks crossover trial (6 w stimulation +2 w washout +6 w stimulation) [14]. The stimulation group also reported far fewer side effects in a comparison to oxybutynin. The authors non-specifically documented some degree of difficulty in applying the stimulation in 30% of patients. This might reflect the inconvenience of placing electrodes over S2–S3 dermatomes or the length of the daily treatment session (up to 6 h).

A heterogeneous group of neurogenic patients with urinary symptoms were investigated in a non-randomized trial using a TENS machine with electrodes placed above the natal cleft twice a day in a home setting [15]. Nineteen out of 44 patients decided to keep the machine after this trial, consistent with the beneficial treatment effect size reported.

Another small trial of 18 patients (7 neurogenic bladder, 5 OAB, 6 nocturia) reported an improvement in 10/18 after 1 month of stimulation over the posterior sacral foramina [11]. The authors suggested that this type of therapy causes less discomfort than vaginal or anal plug stimulation. However, in contradiction of this statement, they reported that in some cases the intensity was not set to a high enough level to produce significant effects in all of the patients.

3.2. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)

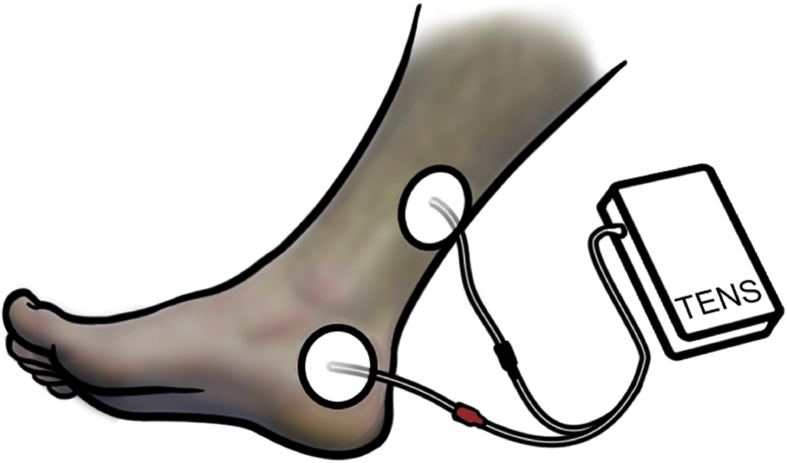

McGuire et al. [16] first used peripheral electrical stimulation to stimulate the PTN. In this initial study an anode electrode was placed over the common peroneal nerve or PTN and a cathode electrode was placed over the contralateral equivalent site. They reported positive results in 8/11 detrusor overactivity patients who became dry after the treatment, and in seven neurogenic disease patients (multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury) of whom five became dry or improved. Following this, the SANS and later the Urgent-PC device established a substantial evidence base using the percutaneous approach to stimulate PTN, although a different location to the original description by McGuire et al. was used. Further studies of either percutaneous or transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (TPTNS) have used electrodes placed on the same area as the SANS (Fig. 2) [6]. Hence TPTNS might be a plausible and potentially attractive therapeutic option based on the evidence available for its efficacy in percutaneous form.

Figure 2.

Position of electrodes for transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (TPTNS). Stimulation can be delivered using a conventional transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machine.

The subjective efficacy of TPTNS and oxybutynine versus control was studied in 28 women with OAB [17]. TPTNS was described as improving subjective symptoms with no adverse events but more robust assessment tools and a careful documentation of the aetio-pathology of the studied patients would be needed to draw more detailed conclusions.

A significant improvement in elderly women with urgency urinary incontinence was reported after 12 weeks (once a week) of stimulation in combination with Kegel exercise and bladder training [18]. However, this effect was not superior to patients in a group receiving no stimulation.

In a self-administered TPTNS non-randomized study 83% of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients reported clinical improvement in urgency [19]. This study also confirmed good patient acceptance of the therapy in their home environment.

In a placebo control trial, 37 women with symptoms of idiopathic OAB were randomized into a treatment or sham group with electrodes positioned in the same place for both groups [20]. Urinary frequency significantly improved, both in the treatment group (p = 0.002) and in the sham group (p = 0.025). A statistical significant difference between these groups was not reached, a possible confounding factor being the unequal baseline micturition frequency (13.88 vs. 11.35 per day).

3.3. Other sites of electrical stimulation

One of the first techniques for the treatment of lower urinary tract storage dysfunction stimulated the suprapubic region in patients with painful bladder syndrome [21], [22]. This method was used to relieve abdominal pain, similarly to the principle of TENS when used for the relief of pain presumably. Subsequently these patients also experienced reduced urinary frequency [22]. Two later studies documented an improvement in urodynamic parameters in patients with detrusor overactivity (DO), sensory urgency, or neurogenic problems. However, based on the literature, the efficacy of stimulation of a suprapubic site in patients with OAB symptoms is unproven [23], [24].

Another reported approach has used stimulation of the thigh muscle in spinal cord injury patients to relieve spasticity. In some of these cases, this has led to improvements of urgency incontinence [25] as well as an increase in the maximum cystometry capacity (MCC) and reduced maximum detrusor pressure (MDP) [26], [27]. Further to this 6/19 patients reported clinical improvement in urinary incontinence and frequency extending out to 3 months after treatment [26].

Based on this, at best limited evidence for stimulation at other sites, the most logical approach to be used in transcutaneous electrical stimulation techniques appears to be either sacral stimulation or PTNS as they either directly or indirectly target the S3 spinal cord root.

3.4. Are acute effects of stimulation of clinical significance?

An obvious approach to answer this question would be to assess the effectiveness of electrical stimulation in suppressing detrusor overactivity (DO), chosen because it presents in many patients with OAB symptoms [28]. This has led researchers to investigate the acute effects of electrical stimulation during an urodynamic study.

One hundred and forty-six patients with idiopathic detrusor instability (IDI), sensory urgency, or DO secondary to neurogenic diseases showed improvements in MCC (p = 0.0009) compared to controls (without stimulation) when stimulation was applied over the S3 dermatomes [29]. Similarly Hasan et al. [12] compared stimulation of the same site to sham and control groups. However, comparison of suprapubic, sacral and sham stimulation by Bower et al. [23] did not clearly demonstrated these immediate effects on MCC. The authors concluded that the observed improvement in first desire to void (FDV) in DO patients may not be functionally important, although a significant reduction in maximum detrusor pressure may suggest potential efficacy in DO. Another approach used conditional stimulation to supress bladder contractions in 12 MS patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO) at a sacral site [30] and in eight MS patients at the PTN [31] using a needle electrode. Unfortunately, none of these patient had a positive response in comparison to dorsal penile stimulation in which 10/12 patients were able to suppress detrusor contraction [30]. The dorsal penile nerve is a division of the pudendal nerve and similar effects of electrical stimulation have been shown when stimulating the pudendal nerve both in other human studies [32], [33] and in cat animal models [34], [35]. This nerve is a deep nerve in the pelvic region. Although it has been suggested that it could be targeted using surface electrodes and a specific stimulation waveform [34], [35] we were unable to show any advantages of this waveform over a conventional stimulation waveform [36]. Hence it would appear this nerve can only be targeted using implanted electrodes or needle electrodes at present.

Similarly inconsistent effects apply for acute TPTNS studies, although Amarenco et al. [37] reported positive results in half of the neurogenic disease (MS, SCI, Parkinson's disease) patients he studied. These patients showed a 50% improvement in volume at the first detrusor contraction and/or MCC of more than 50% of the baseline value. A previous urodynamic study showed no significant differences in any of the urodynamic parameters in 36 detrusor overactivity patients [12]. This differing result might arguably be due to different pathologies seen in the patients.

Neither of the two approaches to the investigation of acute effects, at either stimulating site, has clearly and robustly demonstrated effectiveness. Nevertheless, the balance of the literature indicates that patients may benefit from neuromodulation effects which may arise from repeated stimulation sessions rather than a single application. In addition, de Seze et al. [19] concluded that treatment may be effective even in patients who did not respond to an initial acute TTNS applied during urodynamic testing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Which stimulation parameters?

The literature on the stimulation parameters used is summarised in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3. The location of electrodes and range of stimulus parameters are likely to be critical factors in all forms of stimulation. Relevant stimulus parameters include pulse width; pulse repetition frequency; burst length (if applicable) and stimulus intensity (preferably quoted as current as voltage stimulation coupled with uncertain electrode-tissue interface impedance leads to uncertainty as to delivered stimulus strength). The technical description of the stimuli used in some studies does not give all these details.

Table 1.

Literature reviewing the clinical and urodynamic effects of TENS during long-term application.

| Reference | Diagnosis/patients characteristics | n | Site | Stimulus pulse parameters |

Scheme of treatment | Clinical improvement (% of patients) | Urodynamic assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Pulse duration | Intensity | |||||||

| McGuire et al., 1983 [16] | MS, SCI, detrusor instability, IC | 22 | PTN/common peroneal nerve | – | – | – | – | 80% became dry or improved after the treatment | – |

| Hasan et al., 1996 [12] | IDO | 59 | S2–S3 dermatomes, perianal | 50 Hz | 200 μs | Tickling sensation | 2–4 w, 2 groups | 69% urge incontinence, 73% enuresis, 37% urinary frequency (all defined as 50% benefit) | MCC. voided volume, no. of unstable contractions significantly improved |

| Okada et al., 1998 [26] | DH, IDI | 19 | Thigh region | 30 Hz, pattern | 200 μs | Max. below pain | 2 w, 1/d, 20 min | 32% in urinary incontinence and frequency | 11/19 patients MCC increase of more than 50% |

| Walsh et al., 1999 [13] | Refractory IVD | 32 | S3 dermatomes | 10 Hz | 200 μs | – | 1 w, 1/d, 12 h a day | 76% in frequency, 56% reduction in nocturia, urgency symptom score on VAS not significantly improved | – |

| Skeil et al., 2001 [15] | Neurological | 34 | Sacral dermatomes | 20 Hz | 200 μs | Comfortable level | 6 w, 2/day, 90 min | Significant improvement in incontinence episodes and frequency | Not significantly changed |

| Soomro et al., 2001 [14] | IDI | 43 | S3 dermatomes | 20 Hz | 200 μs | Tickling sensation | 6 w/up to 360 min daily crossover | 56% improved by more than 25% in number of daily voids | Not significantly changed in the stimulation study arm |

| Svihra et al., 2002 [17] | OAB | 28 | PTN | 1 Hz | 100 μs | 70% of motor response | 5 s,1/w, 30 min, 3 groups, control | 56% in questionnaires score, control group no sign diff. | – |

| Yokozuka et al., 2004 [11] | Neurogenic, unstable bladder, nocturia | 18 | Sacral S2–S4 dermatomes | 20 Hz 10 s on 5 s off | 300 μs | Anal sphincter contr. | 4 w, 2/day, 15 min | 55% improved in UUI and frequency | 44% increased MCC and inhibited contraction |

| Bellette et al., 2009 [20] | Non neurogenic OAB, women | 37 | PTN | – | – | – | 8 s, 2/w, sham group | Frequency and urgency improved significantly in both groups | – |

| Schreiner et al., 2010 [18] | UUI, elderly women | 51 | PTN | 10 Hz | 200 μs | Some motor response | 12 s, 1/w, 30 min, control | UUI improved significantly in 76% vs. 26.9% patients in the control group | – |

| de Seze et al., 2011 [19] | MS | 70 | PTN | 10 Hz | 200 μs | Below motor response | 3 m, 1/day, 20 min | 83.3% improved in urgency based on warning time, the urgency MHU subscale and frequency | Total no. of detrusor overactivity patients (86%) significantly decreased to 73% |

| Booth et al., 2013 [45] | Bladder/Bowel dysfunction, elderly | 30 | PTN | 10 Hz | 200 μs | Comfort level | 12 s, 2/w, 30 min, sham group | Frequency: 74% vs. 42% in the sham Urgency: 74% vs. 31% in the sham Incontinence: 47% vs. 15% in the sham |

– |

DH, detrusor hyperreflexia; IC, interstitial cystitis; IDI, idiopathic detrusor instability; IDO, idiopathic detrusor overactivity; IVD, irritative voiding dysfunction; MCC, maximum of cystometry capacity; MHU, Mesure du Handicap Urinaire; MS, multiple sclerosis; OAB, overactive bladder; PTN, posterior tibial nerve; SCI, spinal cord injury; SU, sensory urgency; UUI, urge urinary incontinence.

Table 2.

Literature reviewing the acute urodynamic effects of TENS.

| First author year | Diagnosis | n | Site | Stimulus pulse parameters |

Study details | Urodynamic outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Pulse width | Intensity | ||||||

| Hasan et al., 1996 [12] | IDI | 36 | PTN suprapubic | 50 Hz | 200 μs | Tickling sensation | Part of the large study | No significant difference in any of the parameters |

| 59 | S2–S3 T12 (sham) control | 50 Hz | 200 μs | Tickling sensation | 3 groups, sham, control | MCC significantly increased in S2–S3 stimulation in compare to sham and control | ||

| Bower et al., 1998 [23] | DI, SU | 79 | Sacral | 10 Hz | 200 μs | Max. tolerable sensation | 3 groups, sham | increased Max. DP and FDV |

| Suprapubic | 150 Hz | 200 μs | increased Max. DP and FDV | |||||

| Sham | No stimulation | increased MCC in SU pts. | ||||||

| Walsh et al., 2001 [29] | IDI, SU, DH (SCI, MS) | 146 | Perianal dermatomes | 10 Hz | 200 μs | – | Control group | FDV (p = 0.002) and MCC (p = 0.0009) improved in compare to control |

| Amarenco et al., 2003 [37] | MS, SCI, PD, IDI | 44 | PTN | 10 Hz | 200 μs | Below motor response | Acute effect | 48% (21/44) increased volume at FIDC, 34% (15/44) increased MCC |

| Fjorback et al., 2007 [30] | MS | 12 | Sacral | 20 Hz | 500 μs | 50–60 mA | Conditional stimulation | 0/12 were able to supressed detrusor contraction |

| DPN | 20 Hz | 500 μs | 50–60 mA | 10/12 were able to supressed detrusor contraction | ||||

DH, detrusor hyperreflexia; DI, detrusor instability; DPN, dorsal penile/clitoral nerve; FDV, first desire to void; FIDC, first involuntary detrusor contraction; IDI, idiopathic detrusor instability; MCC, maximum of cystometry capacity; MS, multiple sclerosis; PD, Parkinson's diseases; PTN, posterior tibial nerve; SCI, spinal cord injury; SU, sensory urgency.

Table 3.

Summary of reviewed studies according to their type and the site of stimulation.

| Non control | Placebo control | Other form of control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sacral | Yokozuka et al. [11] Skeil and Thorpe [15] Walsh et al. [13] |

Bower et al. [23] Hasan et al. [12] |

Fjorback et al. [30] Walsh et al. [29] Soomro et al. [14] |

| PTNS | Amarenco et al. [37] De Seze et al. [19] McGuire et al. [16] |

Booth et al. [45] Bellette et al. [20] |

Schreiner et al. [18] Svihra et al. [17] Hasan et al. [12] |

| Suprapubic/other | Okada et al. [26] | Bower et al. [23] | Hasan et al. [12] |

To achieve sacral stimulation Yokozuka et al. [11] instructed patients to put surface electrodes on the posterior sacral foramen and to increase stimulation intensity until an anal contraction could be felt. They speculated that, in cases where there was no improvement, electrodes were not placed in the correct position or the intensity was not high enough due to associated discomfort. There is support by Takahashi and Tanaka [38] where slight changes in electrode location produced considerable apparent changes in urethral pressure response [11]. The sacral stimulation studies reported to date usually have electrodes positioned at the sacral foramina or on the buttocks overlying the S2 and S3 dermatomes. The precise positioning of electrodes on sacral sites varies between studies, presumably because the location of the sacral dermatomes is uncertain [39], [40]. The intensity of the stimulation current was usually set to a maximum dictated by pain threshold. In other studies, patients were instructed to set an intensity that produced a tickling sensation [12], [14], [15]. Nerve trunks (roots) in these areas are located deep within foramina and it is unlikely that these were being directly stimulated at the stimulus intensity level being used. However, cutaneous nerves within the dermatomes are easy to stimulate and hence superficial sensory fibre stimulation, which may lead to both direct and indirect modulation of spinal cord reflexes mechanisms, may explain the reported effects. Furthermore, the intensity which produces anal sphincter contraction [11] involves stimulation of motor nerves thus activating different mechanisms and indeed may cause significant discomfort to the patients. The clarification of the exact site of stimulation and of the intensity required needs to be addressed in future work. Based on the evidence available we are not able to conclude what are the best stimulation parameters to be used for sacral stimulation. The original description of PTNS by McGuire et al. [16] has not been repeated in terms of the location of electrodes. Most studies place electrodes near the medial malleolus, where the PTN is relatively superficial. It is uncertain as to which leg the electrodes need to be placed on for optimal response, and whether this matters; some authors placed electrode on the left leg [17], [20], [37], while others on the right leg [18], [19], [31]. It may also be more effective to place the electrodes bilaterally although no studies have yet looked at this. In describing the setting of current intensity, some of the studies reported motor responses during stimulation [17], [18]. In other studies, the stimulation intensity was set either just below the motor threshold [37] or just above the perception threshold [19].

The study reporting the most promising therapeutic results is that of de Seze et al. [19], which reported PTNS to be successful for OAB symptoms in MS patients. Stimulation intensity in this study was set just around the perception threshold and patients did not report motor responses as a consequence of the stimulation. Hence only sensory fibres or cutaneous nerves overlying the PTN are likely to have been stimulated, which suggests this may be sufficient for the treatment of OAB. If the treatment is self-administered, it is likely that the patient would prefer lower stimulation levels, which may then lead to stimulation of only cutaneous nerves rather than the posterior tibial nerve itself.

4.2. Sham stimulation methodology

Investigation of possible placebo effects is arguably essential in the study of new therapies and this is particularly the case with electrical stimulation techniques because of the sensations they cause. However, because of these sensations, the production of sham electrical stimulation can be difficult. An interesting methodology for sham was performed in a study of children with OAB where, in one arm of the study, stimulation was applied over the scapula, where no effects on lower urinary tract control would be expected to occur [41]. Similarly Hasan et al. [12] applied TENS over the T12 dermatome which acted as a placebo.

Electrical stimulation below motor threshold levels causes tingling sensations due to stimulation of cutaneous sensory nerve structures. An alternative option for a sham methodology may be to gradually decrease the stimulation intensity to zero after a few seconds of usage and to indicate to the subject that stimuli sensation might fade with time. This is an approach widely used in techniques such as transcranial direct current stimulation [42]. Additionally, the subject may habituate to the stimuli such that they are genuinely not able to recognise whether the stimulation still persists or not. This habituation is likely to depend on the stimulation frequency used, the strength of the applied stimuli and on personal subjective responses.

Another approach in investigating placebo effects may be to apply electrodes over the same area of the skin but with no stimulation current using stimulators modified for this purpose [43]. However, this assumes that the patient must be naive to electrical stimulation and hence unaware that it causes sensation.

Leroi et al. [44] performed a randomised sham-controlled trial in which patients were not told that they might receive sham stimulation. Patients were then randomized into active and sham stimuli groups. This methodology was approved by their local ethics committee, although the editors of the journal in which they subsequently published strongly discourage further investigators to use this methodology as they thought it might represent a breach of the Declaration of Helsinki. We think, that this is a justifiable approach to overcome the technical problems of sham stimuli subject to it being approved by the appropriate ethics committee. However, the benefit to the patient of such an arrangement needs to be considered and the offering of active treatment after the study could address this issue.

5. Conclusion

The choice of stimulation parameters, the location of the applied stimulation, the outcome measures used and the underlying conditions and symptoms studied are very diverse in the literature to date. There is little long-term follow-up data published in the literature and hence the treatment regimen to produce on-going benefits is unclear.

The current consensus is that the most promising site of stimulation is the S3 area of the spinal cord over the sacral region or over the posterior tibial nerve, but it is not clear which approach to stimulus delivery is the most effective. Little is known about the underlying mechanisms of action and which exact structures need to be stimulated.

However there is tantalising evidence for efficacy of the transcutaneous stimulation approach, although further large placebo-controlled studies are required to provide a robust evidence base. Standardisation of future trial methodology is important to allow comparisons to be made between studies and stimulation protocols.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the European Commission's Research and Innovation Framework programme (Marie Curie Actions Initial Training Network) for the TRUST project (Training Urology Scientists to Develop Treatments) Grant Number 238541. The study formed part of the project portfolio of the NIHR Devices for Dignity Healthcare Technology Cooperative. We would like to thank Emma Gugon for the sketch of TPTNS.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Urological Association and SMMU.

References

- 1.Abrams P., Cardozo L., Fall M., Griffiths D., Rosier P., Ulmsten U. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapple C.R., Artibani W., Cardozo L.D., Castro-Diaz D., Craggs M., Haab F. The role of urinary urgency and its measurement in the overactive bladder symptom syndrome: current concepts and future prospects. BJU Int. 2005;95:335–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brindley G.S. The first 500 patients with sacral anterior root stimulator implants: general description. Paraplegia. 1994;32:795–805. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt R.A., Jonas U., Oleson K.A., Janknegt R.A., Hassouna M.M., Siegel S.W. Sacral nerve stimulation for treatment of refractory urinary urge incontinence. Sacral Nerve Stimulation Study Group. J Urol. 1999;162:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanagho E.A. Concepts of neuromodulation. Neurourol Urodyn. 1993;12:487–488. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930120508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoller M. Afferent nerve stimulation for pelvic floor dysfunction. Eur Urol. 1999;35:132. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters K.M., Carrico D.J., Perez-Marrero R.A., Khan A.U., Wooldridge L.S., Davis G.L. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus sham efficacy in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome: results from the SUmiT trial. J Urol. 2010;183:1438–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDiarmid S.A., Peters K.M., Shobeiri S.A., Wooldridge L.S., Rovner E.S., Leong F.C. Long-term durability of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the treatment of overactive bladder. J Urol. 2010;183:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bristow S.E., Hasan S.T., Neal D.E. TENS: a treatment option for bladder dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7:185–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01907070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tellenbach M., Schneider M., Mordasini L., Thalmann G.N., Kessler T.M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: an effective treatment for refractory non-neurogenic overactive bladder syndrome? World J Urol. 2013;31:1205–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0888-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokozuka M., Namima T., Nakagawa H., Ichie M., Handa Y. Effects and indications of sacral surface therapeutic electrical stimulation in refractory urinary incontinence. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:899–907. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr803oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasan S.T., Robson W.A., Pridie A.K., Neal D.E. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and temporary S3 neuromodulation in idiopathic detrusor instability. J Urol. 1996;155:2005–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh I.K., Johnston R.S., Keane P.F. Transcutaneous sacral neurostimulation for irritative voiding dysfunction. Eur Urol. 1999;35:192–196. doi: 10.1159/000019846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soomro N.A., Khadra M.H., Robson W., Neal D.E. A crossover randomized trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and oxybutynin in patients with detrusor instability. J Urol. 2001;166:146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skeil D., Thorpe A.C. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in the treatment of neurological patients with urinary symptoms. BJU Int. 2001;88:899–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuire E.J., Zhang S.C., Horwinski E.R., Lytton B. Treatment of motor and sensory detrusor instability by electrical stimulation. J Urol. 1983;129:78–79. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51928-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svihra J., Kurca E., Luptak J., Kliment J. Neuromodulative treatment of overactive bladder–noninvasive tibial nerve stimulation. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2002;103:480–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiner L., dos Santos T.G., Knorst M.R., da Silva Filho I.G. Randomized trial of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation to treat urge urinary incontinence in older women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2010;21:1065–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Seze M., Raibaut P., Gallien P., Even-Schneider A., Denys P., Bonniaud V. Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for treatment of the overactive bladder syndrome in multiple sclerosis: results of a multicenter prospective study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:306–311. doi: 10.1002/nau.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellette P.O., Rodrigues-Palma P.C., Hermann V., Riccetto C., Bigozzi M., Olivares J.M. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation in the management of overactive bladder: a prospective and controlled study. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(09)74003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fall M., Carlsson C.A., Erlandson B.E. Electrical stimulation in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1980;123:192–195. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55850-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fall M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in interstitial cystitis. Update on clinical experience. Urology. 1987;29(4 Suppl.):40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bower W.F., Moore K.H., Adams R.D., Shepherd R. A urodynamic study of surface neuromodulation versus sham in detrusor instability and sensory urgency. J Urol. 1998;160(6 Pt 1):2133–2136. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199812010-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radziszewski K., Zielinski H., Radziszewski P., Swiecicki R. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of urinary bladder in patients with spinal cord injuries. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shindo N.J.R. Reciprocal patterned electrical stimulation of the lower limbs in severe spasticity. Physiotherapy. 1987;73:580–582. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada N., Igawa Y., Ogawa A., Nishizawa O. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of thigh muscles in the treatment of detrusor overactivity. Br J Urol. 1998;81:560–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheeler J.S., Jr., Robinson C.J., Culkin D.J., Bolan J.M. The effect of thigh muscle reconditioning by electrical stimulation on urodynamic activity in SCI patients. J Am Paraplegia Soc. 1986;9(1–2):16–23. doi: 10.1080/01952307.1986.11785939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyndaele J.J., Van Meel T.D., De Wachter S. Detrusor overactivity. Does it represent a difference if patients feel the involuntary contractions? J Urol. 2004;172(5 Pt 1):1915–1918. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000142429.59753.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh I.K., Thompson T., Loughridge W.G., Johnston S.R., Keane P.F., Stone A.R. Non-invasive antidromic neurostimulation: a simple effective method for improving bladder storage. Neurourol Urodyn. 2001;20:73–84. doi: 10.1002/1520-6777(2001)20:1<73::aid-nau9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fjorback M.V., Van Rey F.S., Rijkhoff N.J., Nohr M., Petersen T., Heesakkers J.P. Electrical stimulation of sacral dermatomes in multiple sclerosis patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:525–530. doi: 10.1002/nau.20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fjorback M.V., van Rey F.S., van der Pal F., Rijkhoff N.J., Petersen T., Heesakkers J.P. Acute urodynamic effects of posterior tibial nerve stimulation on neurogenic detrusor overactivity in patients with MS. Eur Urol. 2007;51:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spinelli M., Malaguti S., Giardiello G., Lazzeri M., Tarantola J., Van Den Hombergh U. A new minimally invasive procedure for pudendal nerve stimulation to treat neurogenic bladder: description of the method and preliminary data. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:305–309. doi: 10.1002/nau.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vodusek D.B., Light J.K., Libby J.M. Detrusor inhibition induced by stimulation of pudendal nerve afferents. Neurourol Urodyn. 1986;5:381–389. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tai C., Shen B., Wang J., Liu H., Subbaroyan J., Roppolo J.R. Inhibition of bladder overactivity by stimulation of feline pudendal nerve using transdermal amplitude-modulated signal (TAMS) BJU Int. 2012;109:782–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tai C., Shen B., Wang J., Subbaroyan J., Roppolo J.R., de Groat W.C. Bladder inhibition by intermittent pudendal nerve stimulation in cat using transdermal amplitude-modulated signal (TAMS) Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;37:1181–1184. doi: 10.1002/nau.22241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slovak M., Barker A.T., Chapple C.R. The assessment of a novel electrical stimulation waveform recently introduced for the treatment of overactive bladder. Physiol Meas. 2013;34:479–486. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/34/5/479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amarenco G., Ismael S.S., Even-Schneider A., Raibaut P., Demaille-Wlodyka S., Parratte B. Urodynamic effect of acute transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in overactive bladder. J Urol. 2003;169:2210–2215. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067446.17576.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi K.N.T., Tanaka S. Effect of sacral surface therapeutic electrical stimulation on the lower urinary tract in urinary disturbance. Sogo Rehabiriteshon. 2001;29:851–858. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee M.W., McPhee R.W., Stringer M.D. An evidence-based approach to human dermatomes. Clin Anat. 2008;21:363–373. doi: 10.1002/ca.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg S.A. The history of dermatome mapping. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:126–131. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lordelo P., Teles A., Veiga M.L., Correia L.C., Barroso U., Jr. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with overactive bladder: a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2010;184:683–689. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo R., Wallace D., Fitzgerald P.B., Cooper N.R. Perception of comfort during active and sham transcranial direct current stimulation: a double blind study. Brain Stimul. 2013;6:946–951. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagstroem S., Mahler B., Madsen B., Djurhuus J.C., Rittig S. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for refractory daytime urinary urge incontinence. J Urol. 2009;182(4 Suppl.):2072–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leroi A.M., Siproudhis L., Etienney I., Damon H., Zerbib F., Amarenco G. Transcutaneous electrical tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of fecal incontinence: a randomized trial (CONSORT 1a) Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1888–1896. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Booth J., Hagen S., McClurg D., Norton C., Macinnes C., Collins B. A feasibility study of transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for bladder and bowel dysfunction in elderly adults in residential care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]