ABSTRACT

Previous work showed that the activation of protein kinase A (PKA) signaling promoted mitochondrial fusion and prevented podocyte apoptosis. The cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) is the main downstream transcription factor of PKA signaling. Here we show that the PKA agonist 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate–cyclic AMP (pCPT-cAMP) prevented the production of adriamycin (ADR)-induced reactive oxygen species and apoptosis in podocytes, which were inhibited by CREB RNA interference (RNAi). The activation of PKA enhanced mitochondrial function and prevented the ADR-induced decrease of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I subunits, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex (ND) 1/3/4 genes, and protein expression. Inhibition of CREB expression alleviated pCPT-cAMP-induced ND3, but not the recovery of ND1/4 protein, in ADR-treated podocytes. In addition, CREB RNAi blocked the pCPT-cAMP-induced increase in ATP and the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC1-α). The chromatin immunoprecipitation assay showed enrichment of CREB on PGC1-α and ND3 promoters, suggesting that these promoters are CREB targets. In vivo, both an endogenous cAMP activator (isoproterenol) and pCPT-cAMP decreased the albumin/creatinine ratio in mice with ADR nephropathy, reduced glomerular oxidative stress, and retained Wilm's tumor suppressor gene 1 (WT-1)-positive cells in glomeruli. We conclude that the upregulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins played a partial role in the protection of PKA/CREB signaling.

KEYWORDS: podocyte, PKA signaling, CREB, mitochondria, apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

Podocytes are highly terminally differentiated cells and extend foot processes to the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), which forms a slit diaphragm between two adjacent podocytes (1, 2). A body of literature has documented that podocyte injury is a key factor in focal segmental glomerular sclerosis, which occurs in many glomerular diseases and leads to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (3–5). Various physical and chemical factors can cause cellular injury and may lead to podocyte loss. The mechanism of decline of the podocyte population is not yet fully understood. However, some studies have indicated that apoptosis is the primary contributor (6, 7).

The results of our previous study suggest that the activation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling can prevent puromycin aminonucleoside (PAN)- or adriamycin (ADR)-induced podocyte apoptosis in a mouse nephropathy model (8). Other studies have shown that the activation of cAMP signaling protects podocytes by regulating cell morphology, cytoskeleton rearrangement, cell matrix production, and cell cycle regulation, thereby reducing podocyte loss and proteinuria (9–11). Protein kinase A (PKA), but not the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac), mediates the protective effect of cAMP in podocytes (12). However, little is known about the key downstream protective molecules of cAMP/PKA signaling in podocytes. Intracellular PKA phosphorylates and modulates the activity of ion channels, cellular motor proteins, and many regulatory proteins, including phospholipase C, protein kinase C (PKC), phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and inositol trisphosphate receptors (13). The canonical PKA signaling performs its function via downstream transcription factor response element binding protein (CREB), which plays a vital role in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation (14, 15).

Some studies reported that mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in podocyte injury (16, 17). The results of our previous study revealed that PKA signaling prevented PAN-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis in podocytes, suggesting that mitochondrial function may be important in this process (12). In fact, the primary function of mitochondria is oxidative phosphorylation for the supply of energy to cells (18). As previously demonstrated, a high level of ATP is required for the maintenance of podocyte structure and function (19). Therefore, the role of PKA signaling in podocyte mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and production of ATP needs to be elucidated.

RESULTS

pCPT-cAMP prevented ADR-induced podocyte apoptosis.

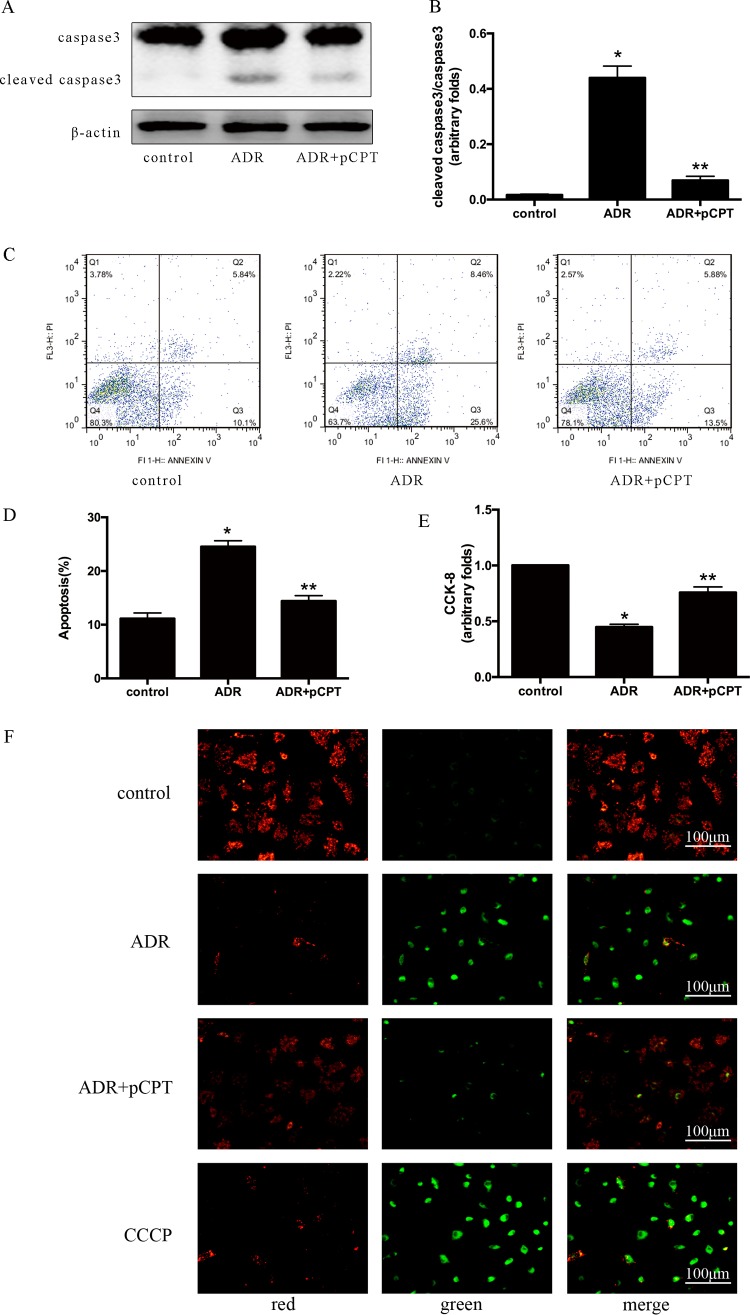

Our previous studies found that cAMP signaling prevented ADR-induced podocyte apoptosis (8), and we further validated whether it is mediated by downstream PKA signaling. Caspase 3 is a key enzyme involved in cell apoptosis, and the increased expression of cleaved caspase 3 is considered an important marker of apoptosis (20). After 72 h of incubation with ADR, the expression of cleaved caspase 3 was increased in podocytes and was blocked by 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate–cAMP (pCPT-cAMP) pretreatment (Fig. 1A and B). Annexin V-propidium iodide (PI) staining showed that the number of apoptotic podocytes was increased by 13.400% ± 1.010% compared with that in the control group (P < 0.05). In contrast, pCPT-cAMP pretreatment decreased the number of apoptotic podocytes by 10.400% ± 1.104% compared with that in the ADR group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1C and D). Consistent with the results of cell apoptosis, the viability of podocytes was decreased significantly after ADR treatment and was partially restored in podocytes pretreated with pCPT-cAMP. Cell viability was 40.45% ± 6.78% and 69.80% ± 5.48% in the ADR and pCPT-cAMP groups, respectively, compared with that in the control group (Fig. 1E). The decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) is an important event in the early stage of apoptosis (21). The change in fluorescence from red to green after 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) staining indicated that pCPT-cAMP prevented the reduction of the ADR-induced Δψm (Fig. 1F). Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) is a kind of efflux pump inhibitor which is usually used as a positive control to induce mitochondrial membrane potential decrease (22).

FIG 1.

PKA signaling prevented ADR-induced podocyte apoptosis. (A and B) Representative immunoblot and corresponding graph of podocytes treated with ADR (0.25 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of pCPT-cAMP (50 μmol/liter) for the indicated periods. Each bar represents data obtained from five independent experiments. (C and D) Detection of cell apoptosis by annexin V-PI staining. Data were obtained from at least three independent assays. (E) Evaluation of cell viability using the CCK-8 assay. (F) JC-1 staining of podocytes (original magnification, ×200). Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was used as a positive control of mitochondrial membrane potential decrease. *, P < 0.05 compared with the control group; **, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR group. pCPT, pCPT-cAMP.

CREB partially mediated the protective effect of PKA signaling in podocytes.

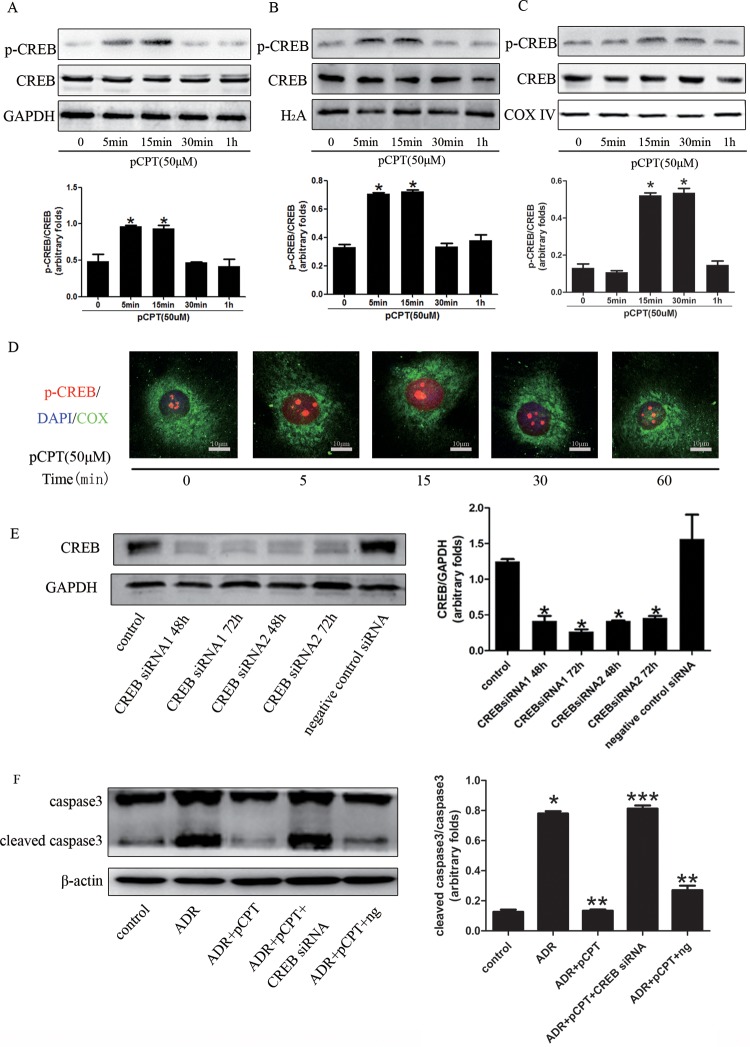

CREB is the main downstream transcription factor of PKA signaling; an increase in the level of phosphorylated CREB means that the PKA signaling is activated (12). As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the expression of phosphorylated CREB started to increase in both whole-cell lysates and nuclei after 5 min of incubation of podocytes with pCPT-cAMP and remained elevated until 15 min of incubation. CREB was also expressed in mitochondria and affects the transcription of mitochondrial genes (23). Mitochondrial proteins were isolated, and the expression of phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) was increased in mitochondria and after 15 min of cell treatment with pCPT-cAMP (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that CREB may function as a transcription factor in mitochondria. Immunofluorescence staining showed that p-CREB was expressed primarily in the nuclei (Fig. 2D). In order to assess whether the protection conferred by PKA signaling depended on the activation of CREB, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down the expression of CREB (Fig. 2E). As shown in Fig. 2F, the silencing of CREB prevented PKA signaling and induced decreased levels of cleaved caspase 3.

FIG 2.

CREB silencing weakened the protective effect of PKA signaling in podocytes. (A to C) Western blots of podocytes treated with pCPT (50 μmol/liter) for the indicated periods. Each bar represents data obtained from five independent experiments. (D) Detection of p-CREB expression in podocytes by immunofluorescence staining (original magnification, ×400). DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; COX, cytochrome c oxidase IV (used as a reference mitochondrial protein). (E) Representative immunoblots and corresponding graph of CREB in podocytes treated with CREB RNAi or a negative-control siRNA. (F) Representative immunoblots and corresponding graph of cleaved caspase 3 in podocytes. *, P < 0.05 compared with the control group; **, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR group; ***, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR-plus-pCPT-plus-ng group. ng, negative-control siRNA.

PKA signaling increased mitochondrial O2 consumption and ATP generation.

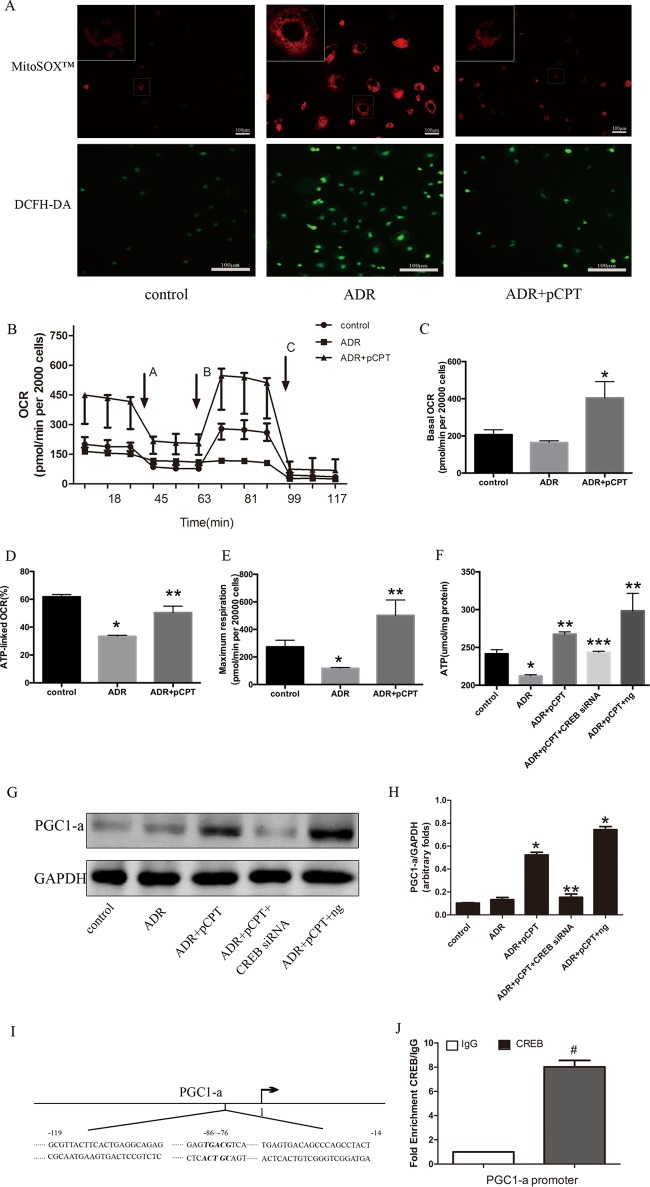

As reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation can induce podocyte apoptosis (24), we then explored whether PKA signaling protects against podocyte injury by reducing oxidative stress. After 24 h of cell treatment with ADR, both mitochondrial superoxide and the ROS index were strongly increased, and this increase was prevented by pCPT-cAMP pretreatment (Fig. 3A). Considering that ADR can cause mitochondrial oxidative damage, the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured in podocytes treated with ADR or ADR plus pCPT-cAMP using the Seahorse Bioscience (Billerica, MA) XF24 extracellular flux analyzer after incubation with four mitochondrial inhibitors: oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor), carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; uncoupler), rotenone (complex I inhibitor), and antimycin A (complex III inhibitor). There was no significant difference in the baseline OCRs between the control group and the ADR group. However, the ATP-linked OCR was lower in the ADR group (61.83% ± 1.58% versus 33.44% ± 0.76%; P < 0.05). FCCP increased OCR in the control and ADR-plus-pCPT-cAMP groups but not in the ADR group. The bioenergetic profile of the ADR-plus-pCPT-cAMP group was distinct from that of the ADR group, with higher baseline OCR, higher ATP-linked OCR, and maximum respiration (Fig. 3B to E). These results suggested the occurrence of mitochondrial dysfunction in ADR-treated podocytes. Therefore, the intracellular ATP concentration was measured. ADR administration reduced the ATP levels by 12.04% ± 2.10%, and these levels were restored to 108.0% ± 2.8% after pretreatment with pCPT-cAMP (Fig. 3F). However, pCPT-cAMP failed to restore the decrease in ATP if CREB expression was inhibited. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC1-α) serves as a potent stimulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration (25) and can bind to several transcription factors and directly affect the expression of respiratory chain components (26). The potential participation of PGC1-α in PKA signaling via upregulation of mitochondrial function was determined by immunoblot analysis, and this analysis indicated that pCPT-cAMP pretreatment increased the expression of PGC1-α significantly in podocytes compared with that in the control group (P < 0.05). However, CREB small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly inhibited this effect (Fig. 3G and H). Similar to the results of a previous study, wherein CREB bound to the CRE region of the PGC1-α promoter (27), the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay performed in the present study indicated that PKA signaling might stimulate the transcription of the PGC1-α gene primarily via CREB (Fig. 3I and J).

FIG 3.

PKA signaling enhanced mitochondrial function. (A) Podocytes were pretreated or not with pCPT (50 μmol/liter) for 48 h and then incubated with ADR (0.25 μg/ml) for another 24 h. Fluorescence microscopy showed the generation of mitochondrial ROS using DCF fluorescence or the mitochondrial superoxide indicator MitoSOX red. (B) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in podocytes from three groups. Each error bar represents data from three wells. Oligomycin (arrow A), carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) (arrow B), and a combination of rotenone and antimycin A (arrow C) were added sequentially to the podocyte culture. (C) The baseline OCR was defined as the OCR before the application of oligomycin. (D) ATP-linked OCR was calculated as the baseline OCR minus the nadir following oligomycin. (E) Maximum respiration was defined as the peak OCR following the application of FCCP. (F) Effects of CREB RNAi on ATP; each bar represents data obtained from five independent experiments. (G and H) CREB silencing blocked the pCPT-cAMP-induced expression of peroxisome PGC1-α. (I) The regions within the PGC1-α promoter were analyzed by ChIP-qPCR. (J) Enrichment of CREB at the PGC1-α promoter. *, P < 0.05 compared with the control group; **, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR group; ***, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR-plus-pCPT-plus-ng group.

PKA signaling prevented ADR-induced downregulation of gene expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex subunit I.

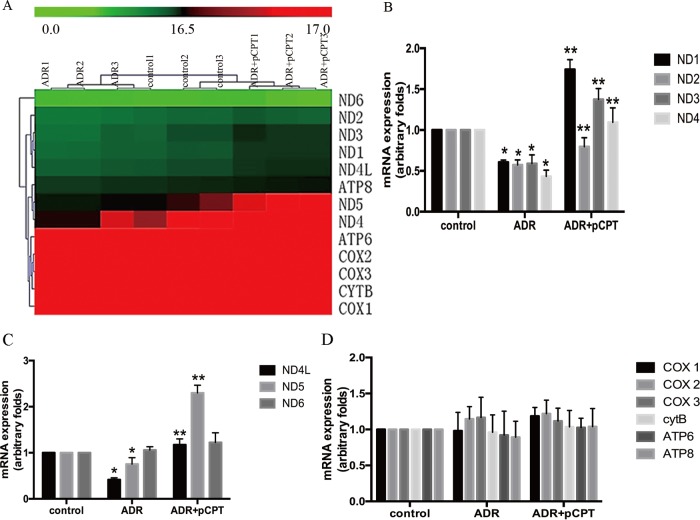

In order to explore the key factors of PKA signaling for podocyte protection, the main downstream genes of PKA signaling involved in the protection of podocytes were explored by performing a genome-wide transcriptome profile analysis. Considering that mitochondrial complexes contribute to the formation of ROS and are involved in many disorders (28), we focused on the change in the gene expression levels of mitochondrial complexes in the control, ADR, and ADR-plus-pCPT-cAMP groups. Thirteen mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)-expressed genes were selected for cluster mapping on the Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV) microarray analysis platform (Fig. 4A). Our results indicated that ADR significantly decreased the mRNA expression of mtDNA-encoded respiratory chain complex I subunits ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND4L, and ND5, and this decrease was prevented by pretreatment with pCPT-cAMP. In contrast, there were no significant differences in the expression of other mtDNA-expressed genes, including those for cytochrome c oxidase (COX) I to III, ATP 6/8, and CytB. Real-time PCR was used to confirm the microarray findings (Fig. 4B to D).

FIG 4.

PKA signaling upregulated the mRNA expression of respiratory chain complex I. (A) Heat map of 13 mitochondrial DNA-expressed genes. The red color indicates a high relative expression and the green color indicates a low relative expression. (B to D) Real-time PCR analysis of the expression of mRNAs in ADR-treated podocytes in the absence or presence of pCPT. Each bar represents data obtained from five independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with the control group; **, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR group.

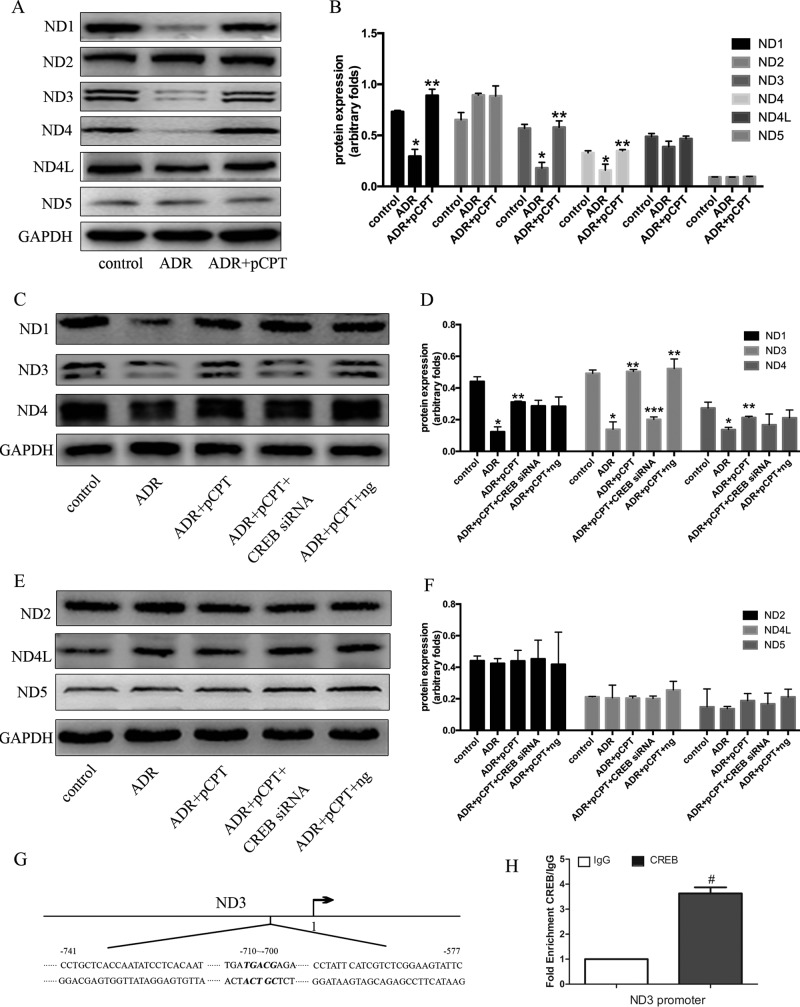

CREB silencing blocked the pCPT-cAMP-induced increase in the protein expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I subunit ND3.

Based on the role of PKA signaling in mitochondrial gene expression, we further validated our results at the protein level. After 72 h of incubation with ADR, the protein expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I subunits ND1, ND3, and ND4 was decreased to 52.1% ± 1.7%, 34.6% ± 2.35%, 54.7% ± 3.06%, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A and B). However, the expression of these proteins was restored to 128.1% ± 12.87%, 105.6% ± 13.5%, and 101.29% ± 6.38%, respectively, after pCPT-cAMP pretreatment compared with that in the ADR group (P < 0.05). RNA interference inhibited CREB expression and blocked the protein expression of pCPT-cAMP-induced ND3 but not the expression of ND1 and ND4 (Fig. 5C to F), suggesting that ND3 may be a potential downstream target gene for CREB. Chromatin immunoprecipitation with anti-CREB antibody followed by qPCR (qPCR) analysis was conducted to assess whether ND3 might be a direct CREB target in podocytes. ChIP-qPCR primers were designed within a 3-kb-long region upstream to the transcription start sites of ND3 genes containing the CREB-binding site. ChIP-qPCR analysis revealed that CREB bound to ND3 within the predicted regions, suggesting that the ND3 gene is a direct target gene for CREB in mouse podocytes (Fig. 5G and H).

FIG 5.

CREB silencing blocked the pCPT-cAMP-induced increase in the protein expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes. (A and B) Representative immunoblots and corresponding graph of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex proteins in podocytes treated with ADR in the absence or presence of pCPT for the indicated periods. (C to F) Representative immunoblots and corresponding graph of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex proteins in podocytes treated with CREB siRNA or a negative-control siRNA. Each bar represents data obtained from five independent experiments. (G) The regions within the ND3 promoter were analyzed by ChIP-qPCR. (H) Enrichment of CREB at the ND3 promoter. *, P < 0.05 compared with the control group; **, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR group; ***, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR-plus-pCPT-plus-ng group.

pCPT-cAMP alleviated ADR-induced ROS generation in injured podocytes.

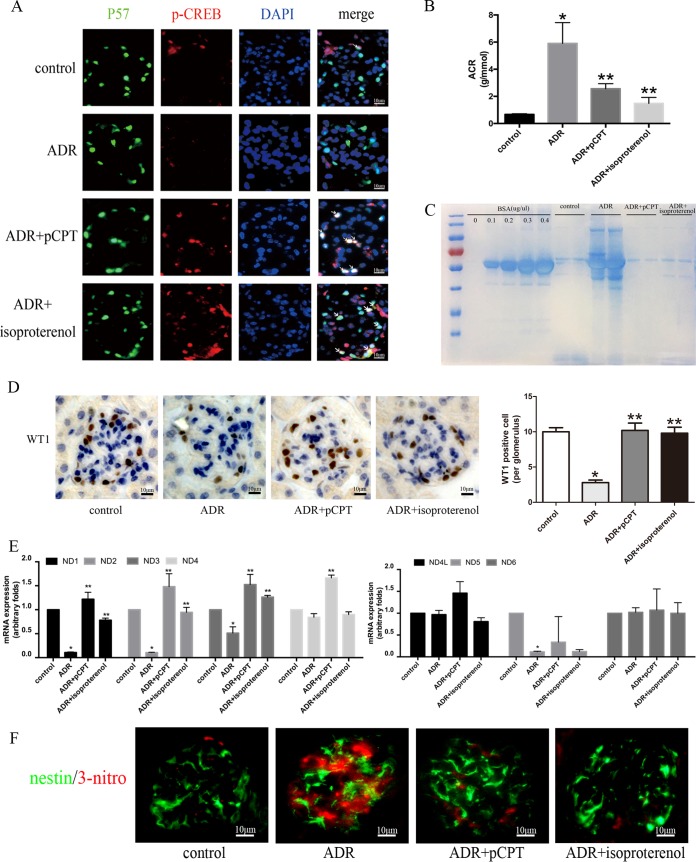

In animal experiments, isoproterenol was used as an endogenous cAMP agonist, and p-CREB staining was increased in mice treated with ADR plus pCPT-cAMP and ADR plus isoproterenol (Fig. 6A). ADR significantly increased the excretion of urinary albumin. However, albumin excretion was decreased in mice treated with ADR plus pCPT-cAMP and ADR plus isoproterenol at the second week (Fig. 6B and C). The average number of podocytes per glomerulus was calculated by WT-1 staining. The numbers of WT-1-positive cells per glomerulus were 10.26 ± 2.79, 3.64 ± 1.86, 10.35 ± 3.62, and 9.86 ± 2.91 (P < 0.05) in the control, ADR, ADR-plus-pCPT-cAMP, and ADR-plus-isoproterenol groups, respectively, in the second week (Fig. 6D), which suggested that the activation of PKA signaling prevented the loss of podocytes. The results of the in vitro study indicated that PKA signaling could prevent ADR-induced podocyte injury by upregulating mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins, thus reducing the production of ROS. For this reason, mouse glomeruli were isolated and analyzed by real-time PCR. The mRNA expression of ND1, -2, -3, and -5 in ADR-treated mice was significantly lower than that of the control group, and pCPT and isoproterenol prevented the downregulation of the mRNA expression of ND1, -2, and -3 but not of ND5 (Fig. 6E). In addition, 3-nitrotyrosine has been reported to be an important marker of oxidative stress (29), consistent with the upregulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex genes; pCPT-cAMP and isoproterenol were also associated with the lower expression of 3-nitrotyrosine than in ADR-treated mice (Fig. 6F).

FIG 6.

pCPT-cAMP alleviated ADR-induced proteinuria, renal oxidative stress, and loss of podocytes. (A) pCPT-cAMP increased p-CREB expression in mouse glomeruli (original magnification, ×400). (B) Albuminuria was expressed as the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) in four groups. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. (C) Urine proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and were resolved by gel electrophoresis. BSA, bovine serum albumin. (D) Immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect WT-1-positive cells in glomeruli (original magnification, ×400). WT-1-positive cells were counted by a single renal pathologist using a blinded method. At least 50 glomeruli per kidney were found. (E) Real-time PCR analysis of the expression of mitochondrial complex mRNAs in isolated glomeruli. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of 3-nitrotyrosine in mouse kidney (original magnification, ×400). Nestin is a marker protein of mature podocytes. *, P < 0.05 compared with the control group; **, P < 0.05 compared with the ADR group.

DISCUSSION

Podocytes play an essential role in the maintenance of the integrity of the glomerular filtration membrane, and injury to this membrane occurs in many glomerular diseases (30). Increasing evidence indicates that intracellular signaling pathways are involved in changes in the biological function of podocytes under different stimuli (31, 32). Our results indicated that PKA signaling might increase mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and reduce ROS generation, thus preventing podocyte injury. CREB activation partly mediated the protection conferred by PKA signaling.

Although some studies demonstrated the protective effect of cAMP signaling in podocytes (33, 34), no direct evidence indicates that cAMP/PKA signaling can reduce proteinuria and protect podocytes in vivo. In the present study, we showed that pCPT-cAMP treatment prevented the ADR-induced increase in the albumin/creatinine ratio and loss of podocytes. Apoptosis is the primary contributor to the loss of podocytes in mice with ADR nephropathy (8). The mechanism of ADR-induced apoptosis in podocytes is unclear. The results of our previous study indicated that mitochondrial function was associated with ADR-induced apoptosis (12). It is well known that mitochondria are essential for oxidative phosphorylation and generation of reactive oxygen species during ATP production (35). Zhu et al. reported that the strong apoptotic response in ADR-treated cells is associated with increased mitochondrial damage and ROS production (36). Therefore, we hypothesized that PKA signaling might prevent ADR-induced apoptosis in podocytes at least in part via protection of mitochondria and inhibition of ROS generation.

CREB is an important transcription factor. Some extracellular stimuli, including peptide hormones and growth factors, can activate protein kinases such as PKA, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs), which, in turn, catalyze the phosphorylation of serine 133 of CREB. CREB plays an indispensable role in almost all life activities by binding to transcriptional coactivators and then to the cAMP response element, consequently regulating the transcription of target genes (37, 38). Similar to the results of Lee et al., in whose study CREB directly regulated gene transcription in the mitochondrial genome (39), our results indicated that after PKA signaling activation, the expression of p-CREB was increased in nuclei and mitochondria. Therefore, CREB may regulate both nuclear and mitochondrial gene transcription in podocytes. Lu et al. found that CREB mediated all-trans retinoic acid-induced cell differentiation in HIV-infected podocytes (40). In the present study, the silencing of CREB only partially blocked the protection conferred by PKA signaling, and this may be due to the following. First, RNAi did not fully suppress CREB expression. Second, CREB is the primary but not the only downstream element of PKA signaling, and the protective effect of PKA signaling may occur by other mechanisms.

Mitochondria are the center of cellular oxidative phosphorylation and ROS generation, and these processes play a key role in cell death and differentiation, congenital immune systems, and metabolic regulation of calcium (41). The mitochondrial respiratory chain is composed of five complexes, and four of them are located in the mitochondrial membrane and are coupled to ADP phosphorylation, providing energy for living cells (42). The primary component in PKA responsible for the protection of podocytes was explored by screening the genome-wide transcriptome and performing cluster analysis. Since mitochondrial dysfunction may be an early event and an important pathogenic factor for podocyte injury (43, 44), we focused on the gene expression of mitochondrial complexes I to V. Our results revealed that the expression of respiratory chain complex I subunits ND1 to -5 was significantly increased in the ADR-plus-pCPT-cAMP group compared with that in the ADR group. Accordingly, Cela et al. demonstrated that the depression of cellular respiration was due to the specific inhibition of complexes I and III and was accompanied by the production of reactive oxygen species (45). Our results suggest that the activation of PKA may upregulate the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins, promote oxidative phosphorylation, and inhibit ROS generation in injured podocytes. What is more, ADR can damage mtDNA directly, by intercalating into mtDNA during transcription and replication, or indirectly, by generating ROS, thus inducing mtDNA damage (46, 47). In our present study, the impressive reversal in podocytes pretreated with pCPT-cAMP should suggest that activation of PKA signaling may prevent doxorubicin-mediated mtDNA damage as well.

Proteins ND1, -3, and -4 are components of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex 1 (28). Although the activation of PKA reversed the downregulation of ADR-induced NDs, it is of note that the silencing of CREB blocked the pCPT-cAMP-induced increase in the protein expression of ND3 but not ND1 or -4, suggesting that other factors may be involved in the PKA signaling-induced increase in the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins. The results of the ChIP assay demonstrated that ND3 is a downstream target gene regulated by CREB. Several studies suggest that subunit ND3 may play a key role in mitochondrial function. Mutations in the ND3 gene had a significant impact on mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I enzymes and led to neonatal mitochondrial encephalopathy (48–50). Therefore, the CREB-induced downregulation of ND3 may be important in injured podocytes. In addition to the generation of ROS, a major function of mitochondria is ATP production (18). A large energy supply ensures protein stability and signal transduction in podocytes (51). PGC1-α is a transcriptional coactivator essential for mitochondrial gene transcription (52). Zhu et al. reported that the dysfunction of the PGC-1α–mitochondrion axis is a primary contributor to ADR-induced podocyte injury (36), and endogenous PGC-1α may be necessary for the maintenance of mitochondrial function in podocytes under standard conditions (53). Previous studies have shown that CREB can activate PGC-1α (54). Similarly, our results revealed that CREB RNAi blocked the pCPT-cAMP-induced increase in ATP and the expression of PGC-1α, suggesting that CREB RNAi may decrease the expression of PGC-1α and to some extent affect the expression of oxidative respiratory chain proteins and ATP production. Signorile et al. reported that serum starvation impaired oxidative phosphorylation in cultured fibroblasts and reduced the expression of phosphorylated CREB, NrF-1, PGC-1α, and TFAM, suggesting that the normal oxidative function of the respiratory chain depends on these transcription activation factors (55).

As adriamycin causes mitochondrial dysfunction that should be universal, some strains (such as C57BL/6 mice) are resistant to ADR-induced renal damage (56). However, there is research demonstrating that endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-deficient C57BL/6 mice developed overt proteinuria and progressive glomerular endothelial cell and podocyte injury when treated with ADR, implying that differences in eNOS production by endothelial cells may account for its resistance to adriamycin of C57BL/6 mice (57). In addition, Papeta et al. demonstrated that a mutation in the protein kinase, DNA-activated, catalytic polypeptide gene (Prkdc) is the underlying cause of susceptibility to ADR nephropathy, a novel role for Prkdc in maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. An 80% to 90% reduction in protein abundance of Prkdc was detected in the kidneys of BALB/c strain mice compared with that in C57BL/6 mice (58).

Glucose is the major energy substrate for most mammalian cells. However, other molecules, including amino acids, nucleosides, and fatty acids, are also metabolized to produce energy in the form of ATP (51). Therefore, the energy metabolism pathways affected by PKA signaling in podocyte protection need to be further investigated.

In conclusion, our results indicated that PKA signaling might upregulate the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes, reduce ROS production, and increase ATP generation, thus preventing ADR-induced podocyte apoptosis. Moreover, the prevention of podocyte apoptosis was at least in part dependent on CREB activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental drugs.

pCPT-cAMP and adriamycin (ADR) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Isoproterenol was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Avonmouth, Bristol, UK).

Urine albumin-creatinine ratio.

Urine protein was determined using Coomassie stain (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China). The urine samples were diluted 20 times with deionized water before degeneration. Proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Urine albumin and creatinine concentrations were determined using an albumin and creatinine assay kit (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China). The absorbance was determined at 510 nm using a microplate reader.

Podocyte culture and treatment.

Conditionally immortalized mouse podocytes were kindly provided by Peter Mundel and were cultured as described previously (59). Most of the analyzed cells had an arborous shape and expressed synaptopodin. Differentiated podocytes were pretreated with pCPT-cAMP for 48 h and treated with ADR for distinct periods. After an additional 24 h of ADR incubation, the treated cells were harvested, stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–propidium iodide (PI), and used for evaluation of mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The treated cells were incubated with ADR for 48 or 72 h for detection of mRNA or protein, respectively. All experiments were repeated at least four times for each indicated condition. Podocytes between passages 9 and 20 were used in all experiments.

Cell component extraction.

Podocyte nuclear extracts were prepared using a nuclear protein extraction kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China). Mitochondria were extracted according to the procedure recommended in the Minute mitochondrion isolation kit (Invent Biotechnology, Plymouth, MN).

Quantification of ROS generation.

Total ROS levels were quantitated by seeding podocytes into a six-well plate. Cells were incubated for 30 min with 10 μmol/liter of dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA). Changes in intracellular ROS levels were determined by measuring the oxidative conversion of cell-permeative 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) to highly fluorescent dichlorofluorescin (DCF). Fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Bensheim, Germany). MitoSOX red mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to detect mitochondrial ROS. Briefly, 1 ml of MitoSOX red reagent working solution (5 μmol/liter) was incubated with podocytes at 37°C in the dark for 10 min, and fluorescence was measured as described previously.

Annexin V-FITC–PI staining.

Podocytes were harvested, incubated with 100 μl of 1× binding buffer containing 5 μl of annexin V-FITC and 5 μl of PI (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and analyzed using flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson FACS Vantage SE).

Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was determined using the dual-emission mitochondrial dye 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) (Beyotime). At low Δψm, the fluorescence of the monomeric form of JC-1 is green (emission at 529 nm). At high Δψm in the mitochondrial matrix, JC-1 forms aggregates and the fluorescence is red (emission at 590 nm).

Quantification of cell viability.

Cell viability was quantified using Cell Counting Kit 8 (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

ChIP-qPCR assay.

A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed using differentiated podocytes with a CREB antibody or immunoglobulin G (IgG) control. Briefly, after sonication, cross-linked DNA was precipitated with anti-CREB antibody (1:50; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) or IgG overnight at 4°C. Purified chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified with primers specific for the following: ND3 (forward, 5′-CCTGCTCACCAATATCCTCACAAT-3′; reverse, 5′-GAATACTTCCGAGACGATGAATAGG-3′) and PGC1-α (5′-forward, GCGTTACTTCACTGAGGCAGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGTAGGCTGGGCTGTCACTCA-3′). Quantitative real-time PCR data were analyzed using an RT2 Profiler PCR array data analysis system (Qiagen, Germantown, TN).

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining.

Cryosections with a thickness of 4 μm were prepared using a cryostat and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After blocking, the cryosections were incubated with primary antibodies and then with a fluorescein Cy3-FITC-labeled secondary antibody (1:100; Proteintech, Wuhan, China). Fluorescence images were recorded using a Leica TCS SP5II confocal microscope (Leica, Bensheim, Germany). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-3-nitrotyrosine (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), p57 antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX), p-CREB antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and rabbit antinestin antibody (1:100; Proteintech). Podocytes were seeded onto clean glass coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100. The slides were incubated with rabbit anti-p-CREB antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-COX IV antibody (1:100; Proteintech), and fluorescein Cy3/FITC-labeled secondary antibody (1:100; Proteintech). Fluorescence images were recorded as described above.

For immunohistochemistry, after deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval, and blocking, the sections were incubated with a primary antibody to WT-1 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and then with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (Beyotime).

RNA extraction, real-time PCR, and microarray hybridization.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After reverse transcription, the RNA samples were denatured and amplified using a LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Amplification conditions were as follows: 45 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 95°C for 10 s, and 60°C for 20 s. The primers used are shown in Table 1. For microarray hybridization, RNA samples were amplified, labeled with Cy3-UTP using the Agilent Quick Amp labeling kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), and hybridized with the Agilent mouse whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray in Agilent's SureHyb hybridization chambers. The mouse whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray contained all known genes and transcripts of the mouse genome. After hybridization and washing, the hybridized slides were scanned using a DNA microarray scanner (Agilent; product no. G2565BA). The results were processed with Agilent Feature Extraction Analytics software (v11.0.0.1) and were imported into Agilent GeneSpring GX software (v12.0) for further analysis. Differentially expressed genes were identified by calculating the fold change (FC) and P values using the t test. Genes with an FC of ≥2 and a P value of ≤0.05 between two groups were considered differentially expressed. The procedure described above was performed by KangChen Bio-Tech (Shanghai, China).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in real-time PCR for the selected genes

| Gene product | Upstream sequence (5′–3′) | Downstream sequence (5′–3′) | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | CCAATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCT | GTTGAAGTCGCAGGAGACAACC | 149 |

| ND1 | TCTAATCGCCATAGCCTTCC | GCGTCTGCAAATGGTTGTAA | 117 |

| ND2 | CCCTTGCCATCATCTACTTCA | GCTGTTGCTTGTGTGACGA | 184 |

| ND3 | TTCGACCCTACAAGCTCTGC | TGAATTGCTCATGGTAGTGGA | 119 |

| ND4 | GGCCTCACATCATCACTCCT | TGGCTATAAGTGGGAAGACCA | 112 |

| ND4L | TGCCATCTACCTTCTTCAACC | CCTTCCAGGCATAGTAATGTGG | 103 |

| ND5 | CCCATGACTACCATCAGCAA | GTGGAATCGGACCAGTAGGA | 103 |

| ND6 | AATACCCGCAAACAAAGATCAC | TGTTGGAGTTATGTTGGAAGGA | 100 |

| Cytb | CAAACCTCCTATCAGCCATCC | AAGTGGAAAGCGAAGAATCG | 109 |

| ATP6 | CTCACTTGCCCACTTCCTTC | GTAAGCCGGACTGCTAATGC | 114 |

| ATP8 | ACATTCCCACTGGCACCTT | GGGTAATGAATGAGGCAAATAG | 102 |

| COXI | CAATGGGAGCAGTGTTTGC | CCAGGAAATGTTGAGGGAAG | 150 |

| COXII | CCTGGTGAACTACGACTGCTA | TCGGTTTGATGTTACTGTTGC | 177 |

| COXIII | CTACCAAGGCCACCACACTC | CGCTCAGAAGAATCCTGCAA | 103 |

RNA interference (RNAi).

CREB small interfering RNA (siRNA) and a negative-control siRNA were purchased from Thermo. siRNA (100 nmol/liter) was transiently transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Thermo Scientific) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Measurement of the oxygen consumption rate.

Mouse podocytes were seeded into 96-well plates for differentiation. After the administration of pCPT-cAMP and ADR, cells were digested, transferred to a V7 cell culture plate (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA) at 2.0 × 104/well, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Then the cells were incubated in bicarbonate-free low-glucose buffered Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) at 37°C without CO2 for 1 h and loaded into an XF24 extracellular analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Different mitochondrial respiratory chain complex inhibitors were loaded into three probes and then injected from the reagent ports automatically to the wells at the desired times (60).

Detection of ATP.

The ATP levels in podocytes were determined by using the luciferin-luciferase method following the protocol of the ATP assay kit (Beyotime). Briefly, cultured cells were harvested and lysed. The supernatant was transferred to a new test tube for an ATP test. The relative ATP level was calculated according to the following formula: relative ATP level = ATP level/protein level.

Immunoblot analysis.

The fractionated cells were extracted and the protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid reagent (Thermo Scientific). Protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting bands were visualized using an Odyssey infrared imaging system. The antibodies used were rabbit anti-caspase 3 antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:5,000, Proteintech), mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibody (1:5,000; Proteintech), rabbit anti-p-CREB antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-CREB antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-H2A antibody (1:2,000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-NADH1 antibody (1:1,000; Proteintech), goat anti-NADH2 antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-NADH3 antibody (1:200; Bioworld, Nanjing, China), rabbit anti-NADH4 antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-NADH4L antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-NADH5 antibody (1:200; Bioworld), and rabbit anti-PGC1-α antibody (1:1,000; Abcam).

Animal experiments.

All animal experiments were performed using a protocol approved by Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. Male specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice (Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal, China) aged 6 to 8 weeks were divided into four groups: a control group, an ADR group, a pCPT-cAMP-treated ADR group, and an isoproterenol-treated ADR group. Nephropathy was induced by a single intravenous injection of 10 mg/kg (of body weight) of ADR. pCPT-cAMP and isoproterenol were administered by intraperitoneal injection at doses of 50 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg 1 h before ADR administration, respectively, followed by daily injections of pCPT-cAMP or isoproterenol until day 14. Urine was collected for 24 h using a metabolic cage on day 13. At day 14, mice were sacrificed under chloral hydrate anesthesia and the kidneys were removed for analyses. Glomeruli were isolated by a sieving method as detailed previously (61).

Statistical analyses.

Quantitative data were representative of those from at least three experiments. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Statistical analyses were conducted using software SPSS v19.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). Analysis of variance followed by Duncan's test and Dunnett's test was used to assess differences between multiple groups. P values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by two scholarships provided to L.G. by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81270781 and 81770665) and the Xinjiang Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2015211C222), a scholarship provided to X.C. by the Xinjiang Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2015211C228), a scholarship provided to A.K. by the Xinjiang Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2015211C227), and a scholarship provided to M.Z. by the Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 15ZR1425900).

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagata M. 2016. Podocyte injury and its consequences. Kidney Int 89:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahamson DR. 2012. Role of the podocyte (and glomerular endothelium) in building the GBM. Semin Nephrol 32:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cara-Fuentes G, Wasserfall CH, Wang H, Johnson RJ, Garin EH. 2014. Minimal change disease: a dysregulation of the podocyte CD80-CTLA-4 axis? Pediatr Nephrol 29:2333–2340. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2874-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maezawa Y, Onay T, Scott RP, Keir LS, Dimke H, Li C, Eremina V, Maezawa Y, Jeansson M, Shan J, Binnie M, Lewin M, Ghosh A, Miner JH, Vainio SJ, Quaggin SE. 2014. Loss of the podocyte-expressed transcription factor Tcf21/Pod1 results in podocyte differentiation defects and FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol 25:2459–2470. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JS, Han BG, Choi SO, Cha SK. 2016. Secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: from podocyte injury to glomerulosclerosis. Biomed Res Int 2016:1630365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Zhu J, Fang M, Zhang T, Xie H, Wang N, Shen N, Guo H, Fu B, Lin H. 2014. Inhibition of p53 deSUMOylation exacerbates puromycin aminonucleoside-induced apoptosis in podocytes. Int J Mol Sci 15:21314–21330. doi: 10.3390/ijms151121314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gong W, Yu J, Wang Q, Li S, Song J, Jia Z, Huang S, Zhang A. 2016. Estrogen-related receptor (ERR) gamma protects against puromycin aminonucleoside-induced podocyte apoptosis by targeting PI3K/Akt signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 78:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu L, Liang X, Wang L, Yan Y, Ni Z, Dai H, Gao J, Mou S, Wang Q, Chen X, Wang L, Qian J. 2012. Functional metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5 are expressed in murine podocytes. Kidney Int 81:458–468. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azeloglu EU, Hardy SV, Eungdamrong NJ, Chen Y, Jayaraman G, Chuang PY, Fang W, Xiong H, Neves SR, Jain MR, Li H, Ma'ayan A, Gordon RE, He JC, Iyengar R. 2014. Interconnected network motifs control podocyte morphology and kidney function. Sci Signal 7:ra12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao H, Li X, Wei K, Xie K, Ni Z, Gu L. 2015. Cyclic AMP prevents decrease of phosphorylated ezrin/radixin/moesin and chloride intracellular channel 5 expressions in injured podocytes. Clin Exp Nephrol 19:1000–1006. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu TC, He JC, Klotman PE. 2007. Podocytes in HIV-associated nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract 106:c67–c71. doi: 10.1159/000101800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Tao H, Xie K, Ni Z, Yan Y, Wei K, Chuang PY, He JC, Gu L. 2014. cAMP signaling prevents podocyte apoptosis via activation of protein kinase A and mitochondrial fusion. PLoS One 9:e92003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang F, Zhang L, Qi Y, Xu H. 2016. Mitochondrial cAMP signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 73:4577–4590. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balogh A, Nemeth M, Koloszar I, Marko L, Przybyl L, Jinno K, Szigeti C, Heffer M, Gebhardt M, Szeberenyi J, Muller DN, Setalo G Jr, Pap M. 2014. Overexpression of CREB protein protects from tunicamycin-induced apoptosis in various rat cell types. Apoptosis 19:1080–1098. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-0986-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altarejos JY, Montminy M. 2011. CREB and the CRTC co-activators: sensors for hormonal and metabolic signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:141–151. doi: 10.1038/nrm3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su M, Dhoopun AR, Yuan Y, Huang S, Zhu C, Ding G, Liu B, Yang T, Zhang A. 2013. Mitochondrial dysfunction is an early event in aldosterone-induced podocyte injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305:F520–F531. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00570.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kopp JB. 2015. Loss of Kruppel-like factor 6 cripples podocyte mitochondrial function. J Clin Invest 125:968–971. doi: 10.1172/JCI80280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas S, Zaganjor E, Haigis MC. 2016. Mitochondria and cancer. Cell 166:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imasawa T, Rossignol R. 2013. Podocyte energy metabolism and glomerular diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45:2109–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weng X, Wang L, Chen H, Liu X, Qiu T, Chen Z. 2015. Ischemic postconditioning inhibits apoptosis in an in vitro proximal tubular cell model. Mol Med Rep 12:99–104. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu MD, Li LY, Li PH, You T, Wang FH, Sun WJ, Zheng ZQ. 2017. Gossypol induces cell death by activating apoptosis and autophagy in HT-29 cells. Mol Med Rep doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu J, Liu X, Li X, Zhang X, Han P, Zhou H, Shao L, Hou Y, Min Y, Kong Z, Wang Y, Wei Y, Liu X, Ni H, Peng J, Hou M. 2016. CD8(+) T cells induce platelet clearance in the liver via platelet desialylation in immune thrombocytopenia. Sci Rep 6:27445. doi: 10.1038/srep27445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Rasmo D, Signorile A, Roca E, Papa S. 2009. cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is imported into mitochondria and promotes protein synthesis. FEBS J 276:4325–4333. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lan X, Lederman R, Eng JM, Shoshtari SS, Saleem MA, Malhotra A, Singhal PC. 2016. Nicotine induces podocyte apoptosis through increasing oxidative stress. PLoS One 11:e0167071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran M, Parikh SM. 2014. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the acutely injured kidney. Nephron Clin Pract 127:42–45. doi: 10.1159/000363715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tengan CH, Rodrigues GS, Godinho RO. 2012. Nitric oxide in skeletal muscle: role on mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Int J Mol Sci 13:17160–17184. doi: 10.3390/ijms131217160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong T, Ning J, Yang X, Liu HY, Han J, Liu Z, Cao W. 2011. Fine-tuned regulation of the PGC-1alpha gene transcription by different intracellular signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300:E500–E507. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00225.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wirth C, Brandt U, Hunte C, Zickermann V. 2016. Structure and function of mitochondrial complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta 1857:902–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whaley-Connell A, Habibi J, Johnson M, Tilmon R, Rehmer N, Rehmer J, Wiedmeyer C, Ferrario CM, Sowers JR. 2009. Nebivolol reduces proteinuria and renal NADPH oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species in the transgenic Ren2 rat. Am J Nephrol 30:354–360. doi: 10.1159/000229305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cellesi F, Li M, Rastaldi MP. 2015. Podocyte injury and repair mechanisms. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 24:239–244. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abkhezr M, Dryer SE. 2015. STAT3 regulates steady-state expression of synaptopodin in cultured mouse podocytes. Mol Pharmacol 87:231–239. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.094508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murea M, Park JK, Sharma S, Kato H, Gruenwald A, Niranjan T, Si H, Thomas DB, Pullman JM, Melamed ML, Susztak K. 2010. Expression of Notch pathway proteins correlates with albuminuria, glomerulosclerosis, and renal function. Kidney Int 78:514–522. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao Z, He L, Takemoto M, Jalanko H, Chan GC, Storm DR, Betsholtz C, Tryggvason K, Patrakka J. 2011. Glomerular podocytes express type 1 adenylate cyclase: inactivation results in susceptibility to proteinuria. Nephron Exp Nephrol 118:e39–48. doi: 10.1159/000320382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keravis T, Monneaux F, Yougbare I, Gazi L, Bourguignon JJ, Muller S, Lugnier C. 2012. Disease progression in MRL/lpr lupus-prone mice is reduced by NCS 613, a specific cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase type 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. PLoS One 7:e28899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macchioni L, Davidescu M, Fettucciari K, Petricciuolo M, Gatticchi L, Gioe D, Villanacci V, Bellini M, Marconi P, Roberti R, Bassotti G, Corazzi L. 2017. Enteric glial cells counteract Clostridium difficile toxin B through a NADPH oxidase/ROS/JNK/caspase-3 axis, without involving mitochondrial pathways. Sci Rep 7:45569. doi: 10.1038/srep45569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu C, Xuan X, Che R, Ding G, Zhao M, Bai M, Jia Z, Huang S, Zhang A. 2014. Dysfunction of the PGC-1alpha-mitochondria axis confers adriamycin-induced podocyte injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306:F1410–F1417. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00622.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen AY, Sakamoto KM, Miller LS. 2010. The role of the transcription factor CREB in immune function. J Immunol 185:6413–6419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sánchez-Muñoz I, Sanchez-Franco F, Vallejo M, Fernandez A, Palacios N, Fernandez M, Cacicedo L. 2010. Activity-dependent somatostatin gene expression is regulated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca2+-calmodulin kinase pathways. J Neurosci Res 88:825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, Kim CH, Simon DK, Aminova LR, Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, Murphy AN, Lonze BE, Kim KS, Ginty DD, Ferrante RJ, Ryu H, Ratan RR. 2005. Mitochondrial cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) mediates mitochondrial gene expression and neuronal survival. J Biol Chem 280:40398–40401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu TC, Wang Z, Feng X, Chuang P, Fang W, Chen Y, Neves S, Maayan A, Xiong H, Liu Y, Iyengar R, Klotman PE, He JC. 2008. Retinoic acid utilizes CREB and USF1 in a transcriptional feed-forward loop in order to stimulate MKP1 expression in human immunodeficiency virus-infected podocytes. Mol Cell Biol 28:5785–5794. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00245-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scatena R. 2012. Mitochondria and drugs. Adv Exp Med Biol 942:329–346. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2869-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meunier B, Fisher N, Ransac S, Mazat JP, Brasseur G. 2013. Respiratory complex III dysfunction in humans and the use of yeast as a model organism to study mitochondrial myopathy and associated diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1827:1346–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mallipattu SK, Horne SJ, D'Agati V, Narla G, Liu R, Frohman MA, Dickman K, Chen EY, Ma'ayan A, Bialkowska AB, Ghaleb AM, Nandan MO, Jain MK, Daehn I, Chuang PY, Yang VW, He JC. 2015. Kruppel-like factor 6 regulates mitochondrial function in the kidney. J Clin Invest 125:1347–1361. doi: 10.1172/JCI77084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casalena G, Krick S, Daehn I, Yu L, Ju W, Shi S, Tsai SY, D'Agati V, Lindenmeyer M, Cohen CD, Schlondorff D, Bottinger EP. 2014. Mpv17 in mitochondria protects podocytes against mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306:F1372–F1380. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00608.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cela O, Piccoli C, Scrima R, Quarato G, Marolla A, Cinnella G, Dambrosio M, Capitanio N. 2010. Bupivacaine uncouples the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, inhibits respiratory chain complexes I and III and enhances ROS production: results of a study on cell cultures. Mitochondrion 10:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lebrecht D, Kokkori A, Ketelsen UP, Setzer B, Walker UA. 2005. Tissue-specific mtDNA lesions and radical-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in human hearts exposed to doxorubicin. J Pathol 207:436–444. doi: 10.1002/path.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Ali AS, Reynolds CM, Welty-Wolf KE, Piantadosi CA. 2007. The CO/HO system reverses inhibition of mitochondrial biogenesis and prevents murine doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 117:3730–3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malfatti E, Bugiani M, Invernizzi F, de Souza CF, Farina L, Carrara F, Lamantea E, Antozzi C, Confalonieri P, Sanseverino MT, Giugliani R, Uziel G, Zeviani M. 2007. Novel mutations of ND genes in complex I deficiency associated with mitochondrial encephalopathy. Brain 130:1894–1904. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McFarland R, Kirby DM, Fowler KJ, Ohtake A, Ryan MT, Amor DJ, Fletcher JM, Dixon JW, Collins FA, Turnbull DM, Taylor RW, Thorburn DR. 2004. De novo mutations in the mitochondrial ND3 gene as a cause of infantile mitochondrial encephalopathy and complex I deficiency. Ann Neurol 55:58–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.10787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leshinsky-Silver E, Lev D, Tzofi-Berman Z, Cohen S, Saada A, Yanoov-Sharav M, Gilad E, Lerman-Sagie T. 2005. Fulminant neurological deterioration in a neonate with Leigh syndrome due to a maternally transmitted missense mutation in the mitochondrial ND3 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334:582–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan K, Ito N, Nakajo A, Kurayama R, Fukuhara D, Nishibori Y, Kudo A, Akimoto Y, Takenaka H. 2012. The struggle for energy in podocytes leads to nephrotic syndrome. Cell Cycle 11:1504–1511. doi: 10.4161/cc.19825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Austin S, St-Pierre J. 2012. PGC1alpha and mitochondrial metabolism–emerging concepts and relevance in ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. J Cell Sci 125:4963–4971. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Y, Huang S, Wang W, Wang Y, Zhang P, Zhu C, Ding G, Liu B, Yang T, Zhang A. 2012. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction and protects podocytes from aldosterone-induced injury. Kidney Int 82:771–789. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh S, Simpson RL, Bennett RG. 2015. Relaxin activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) through a pathway involving PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC1alpha). J Biol Chem 290:950–959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.589325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Signorile A, Micelli L, De Rasmo D, Santeramo A, Papa F, Ficarella R, Gattoni G, Scacco S, Papa S. 2014. Regulation of the biogenesis of OXPHOS complexes in cell transition from replicating to quiescent state: involvement of PKA and effect of hydroxytyrosol. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:675–684. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng Z, Schmidt-Ott KM, Chua S, Foster KA, Frankel RZ, Pavlidis P, Barasch J, D'Agati VD, Gharavi AG. 2005. A Mendelian locus on chromosome 16 determines susceptibility to doxorubicin nephropathy in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2502–2507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409786102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun YB, Qu X, Zhang X, Caruana G, Bertram JF, Li J. 2013. Glomerular endothelial cell injury and damage precedes that of podocytes in adriamycin-induced nephropathy. PLoS One 8:e55027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papeta N, Zheng Z, Schon EA, Brosel S, Altintas MM, Nasr SH, Reiser J, D'Agati VD, Gharavi AG. 2010. Prkdc participates in mitochondrial genome maintenance and prevents Adriamycin-induced nephropathy in mice. J Clin Invest 120:4055–4064. doi: 10.1172/JCI43721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mundel P, Reiser J, Kriz W. 1997. Induction of differentiation in cultured rat and human podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 8:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones AR IV, Meshulam T, Oliveira MF, Burritt N, Corkey BE. 2016. Extracellular redox regulation of intracellular reactive oxygen generation, mitochondrial function and lipid turnover in cultured human adipocytes. PLoS One 11:e0164011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akis N, Madaio MP. 2004. Isolation, culture, and characterization of endothelial cells from mouse glomeruli. Kidney Int 65:2223–2227. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]