ABSTRACT

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a betaherpesvirus that latently infects most adult humans worldwide and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised hosts. Latent human CMV (HCMV) is believed to reside in precursors of myeloid-lineage leukocytes and monocytes, which give rise to macrophages and dendritic cells (DC). We report here that human monocyte-derived DC (mo-DC) suppress HCMV infection in coculture with infected fibroblast target cells in a manner dependent on the effector-to-target ratio. Intriguingly, optimal activation of mo-DC was achieved under coculture conditions and not by direct infection with HCMV, implying that mo-DC may recognize unique molecular patterns on, or within, infected fibroblasts. We show that HCMV is controlled by secreted factors that act by priming defenses in target cells rather than by direct viral neutralization, but we excluded a role for interferons (IFNs) in this control. The expression of lytic viral genes in infected cells and the progression of infection were significantly slowed, but this effect was reversible, indicating that the control of infection depended on the transient induction of antiviral effector molecules in target cells. Using immediate early or late-phase reporter HCMVs, we show that soluble factors secreted in the cocultures suppress HCMV replication at both stages of the infection and that their antiviral effects are robust and comparable in numerous batches of mo-DC as well as in primary fibroblasts and stromal cells.

IMPORTANCE Human cytomegalovirus is a widespread opportunistic pathogen that can cause severe disease and complications in vulnerable individuals. This includes newborn children, HIV AIDS patients, and transplant recipients. Although the majority of healthy humans carry this virus throughout their lives without symptoms, it is not exactly clear which tissues in the body are the main reservoirs of latent virus infection or how the delicate balance between the virus and the immune system is maintained over an individual's lifetime. Here, for the first time, we provide evidence for a novel mechanism of direct virus control by a subset of human innate immune cells called dendritic cells, which are regarded as a major site of virus latency and reactivation. Our findings may have important implications in HCMV disease prevention as well as in development of novel therapeutic approaches.

KEYWORDS: antiviral agents, cytomegalovirus, dendritic cells, fluorescent image analysis, video microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) causes subclinical primary infections in approximately 50 to 100% of healthy individuals, depending on geographic and socioeconomic differences of populations (1). Primary infection is followed by lifelong latent infection, which typically remains asymptomatic. HCMV infection is the most common cause of congenital infections, which may result in birth defects, and a major risk for complications in immune-suppressed and -compromised individuals (2–4). There is no vaccine available against HCMV. Therefore, the immune response and therapeutic strategies against this virus remain subjects of intense study.

HCMV infection elicits a strong immune response (5). The role of natural killer (NK) and T cells in controlling the primary infection as well as in preventing reactivation from latency has been well documented in animal models of cytomegalovirus infection (6, 7). The role of dendritic cells (DC) remains somewhat less clear, partly because HCMV replicates in some DC subsets. The major subsets in humans include myeloid or classical DC (cDC), the plasmacytoid DC (pDC), and the monocyte-related DC (mDC), which include the inflammatory CD1c+ CD16− DC (8). HCMV can initiate a replicative infection in in vitro-generated monocyte-derived DC (mo-DC) (9–12) or in ex vivo-harvested circulating mDC that closely resemble the phenotype of mo-DC (13). HCMV in vitro infection triggers interferon (IFN) and other cytokine responses in mo-DC (14) in a cGAS-dependent manner (15), and this may recruit other immune subsets to the site of infection and coordinate the immune response. On the other hand, HCMV downregulates HLA I expression and upregulates Fas ligand and TRAIL in infected DC, protecting them from cytolytic cells and inducing apoptosis in activated T cells interfacing with them (16). Additionally, HCMV expresses an interleukin-10 (IL-10) homolog in infected cells (17), which suppresses IFN-α/β production in nearby pDC (18, 19). Taken together, these observations indicate that numerous DC subsets interact with HCMV in a pleiotropic manner (20). They are essential for inducing the antiviral NK and T cell responses but are also a target of HCMV infection and immune evasion (21). However, DC responses to HCMV infection have so far been studied only in DC monocultures, probably due to their permissiveness for HCMV and the assumption that mo-DC are triggered by direct viral infection. Notably, we found recently that murine cDC release antiviral factors that control mouse CMV (MCMV) in cocultured fibroblasts or endothelial cells (22).

CMVs have coevolved with the host species and are strictly specific for the respective host cells, impairing our ability to study HCMV biology by in vivo infection models. Nevertheless, there are significant similarities between CMVs of different species at the level of viral genes and their functions (23–25), and the murine CMV (MCMV) is widely used as model of virus-host in vivo interactions. Murine pDC are the major source of a type I interferon response to MCMV infection (26) yet do not support a replicative infection (27). Murine cDC on the other hand can be infected with MCMV but produce smaller amounts of type I IFNs (20, 28). In vivo experiments have shown that DC contribute to the control of CMV infection by indirect mechanisms inducing antiviral responses of NK and T cells (27, 29–31). More recently, we showed direct repression of MCMV infection and spread by bone marrow-derived DC (mDC) (22) in coculture with infected endothelial and fibroblast cells. The antiviral function was mediated by type I IFN secretion as well as by other yet unidentified soluble antiviral factors (22).

We hypothesized that a similar antiviral function may be exerted by HCMV and therefore studied the ability of human mo-DC to control HCMV replication in human endothelial and fibroblast cells. Here, we show a robust dose-dependent control of HCMV replication in fibroblasts cocultured with mo-DC, mediated by soluble factors released into the supernatant (SN). The antiviral factors stimulated the innate antiviral defenses of the target cells and repressed the expression of immediate early (IE) as well as late HCMV genes, thereby slowing the progression of the infection in a reversible manner. In contrast to previously reported results in the murine system, this was not dependent on signaling via interferon alpha/beta receptor (IFNAR). Finally, we show that only cocultures of infected fibroblasts and mo-DC induced supernatants displaying antiviral properties, whereas supernatants from monocultures of HCMV-infected mo-DC were not protective against HCMV spread in human cell lines or in primary human fibroblasts and stromal cell cultures.

RESULTS

Human mo-DC suppress spread of HCMV infection in cocultured human fibroblasts.

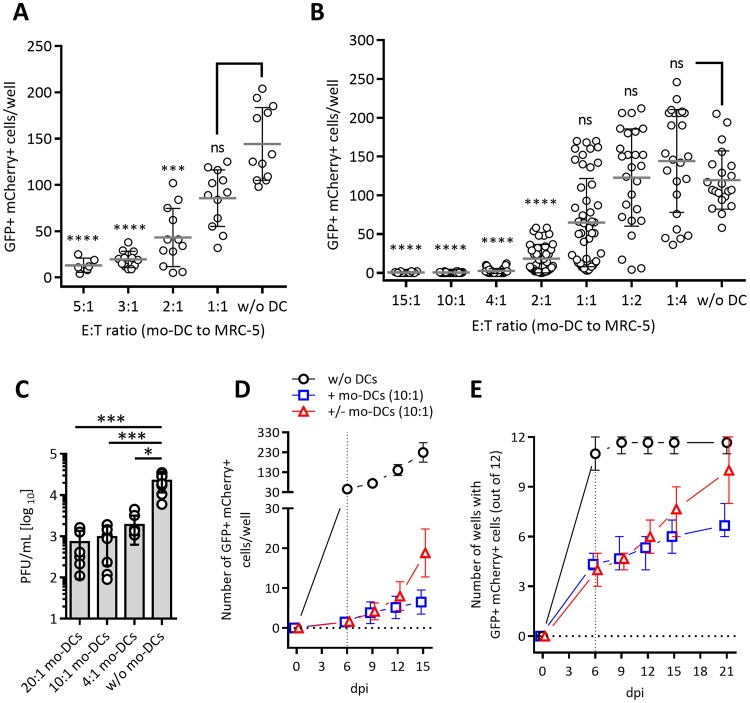

To test the ability of human DC in controlling HCMV replication in coculture with virus-infected target cells, we generated mo-DC populations by differentiating CD14+ blood monocytes using a conventional protocol (32). We infected MRC-5 fibroblasts with a dual-late-gene reporter virus, TB40/E-UL32-GFP/UL100-mCherry (HCMVdLr) (33), at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.0125 PFU per target cell, which enabled reliable counting of infected cells in a 96-well plate format. After 2 h of infection, the virus suspension was removed from cells, and mo-DC (effector cells) were added to the infected MRC-5 cells (target cells) at effector-to-target (E/T) ratios between 5:1 and 1:1 (Fig. 1A; see also the experimental scheme in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). At 5 to 6 days postinfection (dpi), the infected green fluorescent protein (GFP)- and mCherry-expressing MRC-5 cells were identified by epifluorescence microscopy and counted in each well (Fig. 1A). We observed a dose-dependent control of infection that reached statistical significance at an E/T ratio of 2:1, with about a 75% reduction in the number of infected cells (Fig. 1A). To facilitate a faster work flow, we adopted a rapid mo-DC generation protocol, which made it possible to differentiate and mature mo-DC in 4 instead of 9 days (34). We validated the functional similarity of rapidly generated mo-DC to conventionally generated ones by testing virus control in identical settings and included an extended range of E/T ratios (Fig. 1B). We observed the same dose-dependent control starting at E/T ratios of 1:1 to 2:1 and an almost complete absence of infected cells at ratios of 10:1 and 15:1. The mo-DC were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from several CMV-seronegative donors, but despite some variation in potencies among different donors (data not shown), almost all mo-DC batches showed the same robust trend of dose-dependent control. To see if this repression correlated with a reduction of lytic replication of the virus, cells were infected and cocultured with mo-DC at E/T ratios of 20:1, 10:1, and 4:1. At 14 dpi, infectious virus titers in the supernatants were compared to those of control wells infected in the absence of mo-DC by plaque assay; we observed significant reductions in the presence of mo-DC (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Mo-DC suppress spread of the dual-late-reporter HCMVdLr virus in coculture with infected human MRC-5 fibroblasts. Human mo-DC were cocultured at the indicated E/T ratios with MRC-5 cells infected with 375 PFU of HCMVdLr (MOI of 0.0125). Mo-DC were added immediately upon removal of the virus. The numbers of GFP/mCherry-expressing cells at 5 to 6 days postinfection in coculture with conventionally generated (A) or rapidly generated (B) mo-DC are shown. Dot plots depict combined data from at least three independent experiments with mo-DC generated from 6 (A) or 17 (B) PBMC donors. Horizontal lines denote group means, and error bars indicate the standard deviations. (C) Cocultures of infected MRC-5 cells and mo-DC at the indicated E/T ratios in six-well replicates were infected with 1,050 PFU of HCMVIEr (MOI of 0.035). Virus titer in the SN at 6 dpi was established by plaque assay. Symbols indicate individual replicates; bars indicate mean values. Each group was statistically analyzed by nonparametric two-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis) with Dunn's multiple-comparison test against the control (without [w/o] mo-DC) group (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). (D) GFP/mCherry-expressing cells were quantified in MRC-5 cells infected with 45 PFU (MOI of 0.0015) of HCMVdLr in the presence of mo-DC at 6, 9, 12, and 15 dpi (+ mo-DCs), and levels were compared to those of controls infected in the absence of mo-DC (w/o DCs) or those where mo-DC were removed (+/− mo-DCs) at 6 dpi. Plotted are combined data from two independent experiments (means with standard deviations). (E) Cells were infected as described for panel D, but only 6 PFU per well (MOI of 0.0002) was added to MRC-5 cells in 12-well replicates. A well was reported as positive if ≥1 fluorescent cell was observed. The plot depicts combined data from four independent experiments.

To define the kinetics of HCMV spread in the presence of mo-DC, we monitored HCMVdLr-infected cocultures of MRC-5 cells and mo-DC at an E/T ratio of 10:1 over 15 days and compared the results to those under control conditions without mo-DC. To allow for dynamic quantification of infected cells up to 15 dpi, cells were infected with 45 PFU/well (MOI of 0.0015) and counted at 6, 9, 12, and 15 dpi. We observed major differences at every time point, with less than 10 infected cells per well detectable at all times (Fig. 1D, squares), whereas the numbers increased rapidly in control wells lacking mo-DC (Fig. 1D, circles). To assess if the antiviral effect is reversible, mo-DC along with the supernatant content of the well were removed and replaced with fresh medium at 6 dpi, and infection was monitored until 15 dpi (Fig. 1D, triangles). The number of infected cells increased at a higher rate than in wells where mo-DC were left in coculture. To determine if infection can be fully eliminated by the mo-DC or if virus replication may restart even after the virus was entirely contained, cells were infected with HCMVdLr at a much lower MOI of 0.0002 (6 PFU/well), at which level it was reliably possible to detect at least one infected cell per well under control conditions. Six days later, we surveyed all 12 replicate wells for the presence of any infected cell (i.e., a positive well). While almost all control wells contained an infected cell and were therefore positive (Fig. 1E, circles), approximately 8 of 12 mo-DC-containing wells remained negative. Mo-DC were removed (Fig. 1E, triangles) or not (squares) at 6 dpi, and infection was monitored for an additional 15 days. By 21 dpi, almost all previously negative wells from which the mo-DC were removed became positive, whereas this was the case in only a few mo-DC-containing wells (Fig. 1E, squares).

Therefore, monocyte-derived human DC potently suppressed the spread of HCMV infection in cocultured human fibroblasts. This block occurred in a ratio-dependent manner and required continuous surveillance but was independent of the mo-DC generation protocol. Consequently, the rapid mo-DC generation protocol was used in subsequent experiments.

Mo-DC suppress the spread of HCMV and repress expression of MIE genes.

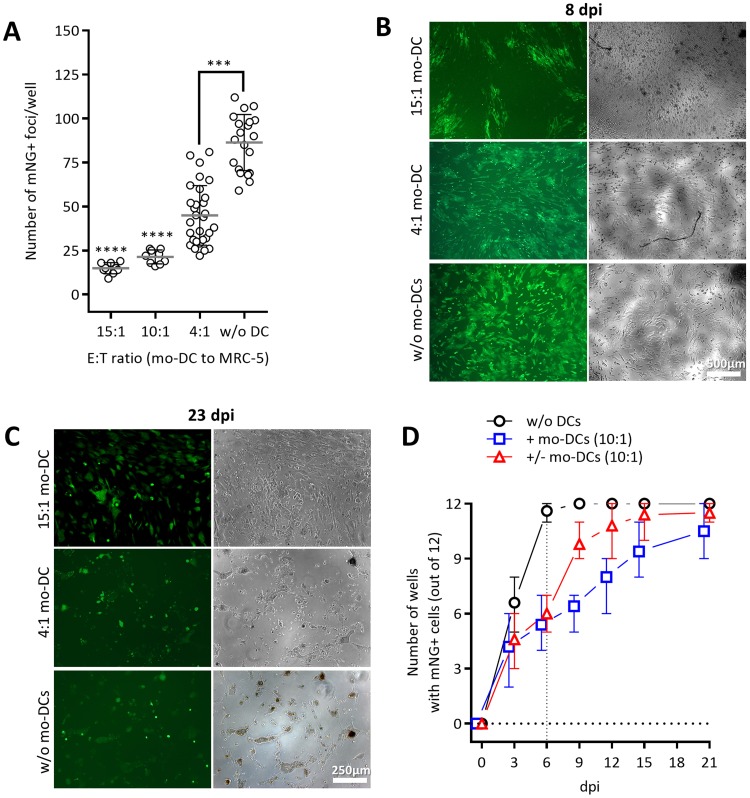

While the coculture with mo-DC reversibly impaired HCMV spread, it remained unclear whether the effects occurred at early or at late stages of the infection cycle. Namely, as the fluorescent reporter genes in HCMVdLr are expressed by late viral promoters, their expression would be affected by blocks in both the early and the late stages. Thus, we generated a novel immediate early reporter virus, TB40/E-UL122/123-mNeonGreen (HCMVIEr), expressing the bright mNeonGreen (mNG) fluorescence protein (35) under the control of the endogenous HCMV major immediate early (MIE) promoter and in equimolar ratio to the total products of the IE1 and IE2 (IE1/2) genes (Fig. S2A). We infected MRC-5 cells with 150 PFU of HCMVIEr (MOI of 0.005), cocultured them with mo-DC at various ratios (Fig. 2), and counted the number of infection foci per well at 3 dpi (Fig. 2A). As observed with the HCMVdLr, mo-DC suppressed the spread of infection in an E/T ratio-dependent manner, yet a complete abrogation of infection could not be achieved even at high ratios. In fact, single infected cells kept appearing over time, and the sizes of infection foci increased even under high E/T ratios. Nevertheless, the progression of infection was significantly slowed in the presence of mo-DC, resulting in a striking contrast between high- and low-ratio conditions (15:1 versus 4:1) and the controls without mo-DC at 8 (Fig. 2B) or 23 (Fig. 2C) dpi. To define if mo-DC may entirely block HCMV spread under ideal conditions, we monitored the mNeonGreen signal upon infection at a very low dose of HCMVIEr (6 PFU/well; MOI of 0.0002) using the same conditions as applied before in the experiment depicted in Fig. 1E. Virtually all control wells (Fig. 2D, circles) were positive at 6 dpi, while approximately half of the 12 wells remained negative in the presence of mo-DC (squares and triangles). Removal of mo-DC at 6 dpi led to a spike in the number of positive wells already 3 days later (Fig. 2D, triangles), and by 15 dpi, all wells from which mo-DC were removed were positive. In contrast to the experiment shown in Fig. 1E, however, the number of positive wells increased even in the continuous presence of mo-DC in coculture (Fig. 2D, squares), albeit at a slower pace; yet by the end of the experiment, almost all wells from all conditions were positive (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

Mo-DC suppress the spread of the immediate early reporter HCMVIEr virus in coculture with infected human fibroblasts. (A) Mo-DC were cocultured at increasing E/T ratios with HCMVIEr-infected MRC-5 cells at 150 PFU/well (MOI of 0.005). mNeonGreen-expressing infection foci were manually quantified in each well at 2 to 3 dpi. The dot plot depicts combined data from four independent experiments with mo-DC generated from five donors; values are means with standard deviations. Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn's multiple-comparison test for each data set against the control data set (without mo-DC) was used (***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001). Representative images are shown from cocultures infected at an MOI of 0.035 (1,050 PFU/well) at 8 (B) and 23 (C) dpi. (D) As described in the legend of Fig. 1E, 6 PFU/well (MOI of 0.0002) of HCMVIEr was added to MRC-5 cells in 12-well replicates. A well was reported as positive if ≥1 fluorescent cell was observed. The plot depicts combined data from five independent experiments (n = 2 for day 21).

We therefore conclude that mo-DC may repress, but not fully block, the expression of HCMV lytic genes. Since the block was more pronounced at late stages (Fig. 1) than at the immediate early one (Fig. 2), our data indicated that the antiviral effects might act at the level of both phases and accumulate with the progression of the infection.

Antiviral function of activated mo-DC is mediated via soluble factors that delay and repress IE gene expression.

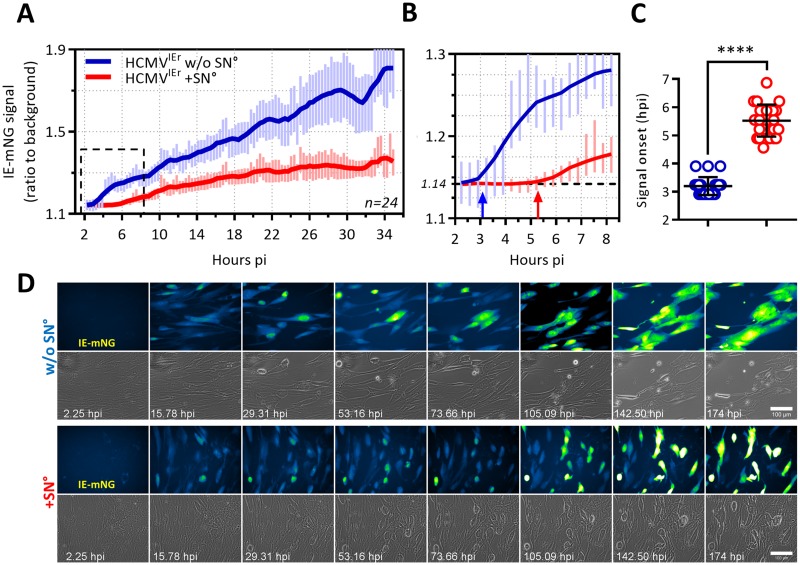

We hypothesized that mo-DC may suppress viral replication by releasing soluble antiviral factors. In that case, viral gene expression would be repressed by conditioned supernatant (SN°) from mo-DC cocultures. To test this, we harvested supernatant of mo-DC cocultured with infected MRC-5 cells at 6 to 8 dpi and filtered it through 0.1-μm-pore-size filters to remove cells and virus particles (Fig. S1B). We followed the early dynamics of HCMV gene expression in real time by live-cell imaging. The infection of MRC-5 fibroblasts with HCMVIEr was synchronized by restricting the infection to a 10-min window (36). SN° was added immediately upon virus removal, and the reporter signal was dynamically monitored and quantified. Under control conditions, the IE reporter signal became detectable at approximately 3 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 3C) and steadily increased as the infection progressed (Fig. 3A and B, blue). In SN°-treated cells, however, the onset of the signal was significantly delayed, starting at approximately 5 hpi (Fig. 3B and C, red) and increased at a reduced rate (Fig. 3A). The intensity of the reporter signal and therefore of IE gene expression increased strikingly faster in untreated control cells (Fig. 3A, blue), and this correlated with prominent changes in cell morphology as well as disruption of the cell monolayer (Fig. 3D, second row; see also Movie S1).

FIG 3.

The antiviral factors from mo-DC delay the onset and repress HCMV IE gene expression in fibroblasts. MRC-5 fibroblasts were infected with HCMVIEr at an MOI of 0.035 using centrifugal enhancement, and medium (blue line) or the antiviral supernatant (from coculture of infected MRC-5 cells and mo-DC, referred to as SN°) (red line) was immediately added to them; infection was followed by epifluorescence time lapse imaging in 24 fields per condition at the rate of one frame per 20 min. (A) Solid lines show three-point smoothing of the average signal ratio (ratio of signal from infected cells to the background signal of the field) from 24 fields, with standard deviations of the average up to 35 h postinfection (p.i.). A representative plot from one of three independent experiments is shown. (B) The signal ratio in untreated cells deviated from the baseline signal ratio (dashed line) at around 3 hpi (blue arrow) while this occurred at >5 h for SN°-treated cells (red arrow). (C) Scatter dot plots show the distribution of signal onset in each field of untreated (blue) and SN°-treated (red) conditions. An unpaired nonparametric t test (Mann-Whitney test) was used (****, P < 0.0001). (D) Representative time series image montages from panel A up to 174 hpi. IE1/2-associated mNeonGreen signal in the GFP channel is depicted in false colors (Fire Blue Green look-up table) for better visibility. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Antiviral function of mo-DC is independent of type I interferon.

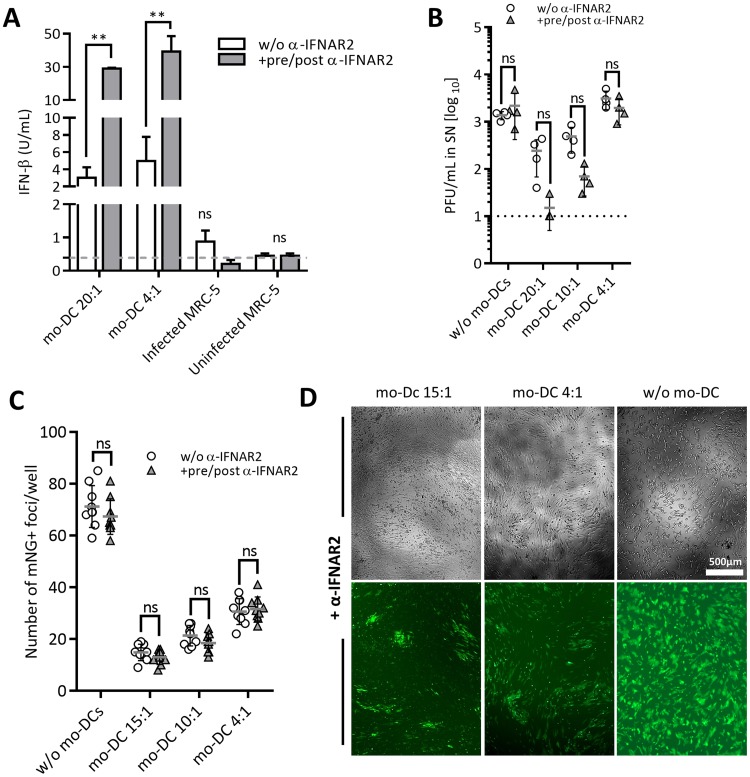

DC are known to secrete interferon (IFN) beta and alpha in response to CMV infection (28), and thus we considered it likely that type I IFNs are the soluble factors repressing HCMV replication in our system. Therefore, we measured the available IFN-β in the mo-DC coculture SN by high-sensitivity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 4A and S3A). The concentration of the available IFN-β was elevated in infected cocultures over levels in MRC-5 monocultures but reached concentrations of only 2 to 8 U/ml at E/T ratios of 20:1 and 4:1. We considered the possibility that the released type I IFNs are immediately bound to receptors on target cells and thus measured IFN levels in the presence of anti-IFNAR2, which blocks attachment of IFN-β to subunit 2 of the heterodimeric common type I IFN receptor IFNAR (37). In the presence of anti-IFNAR2, the IFN-β concentration was significantly higher and reached approximately 30 to 50 U/ml (Fig. 4A). This argued that activated mo-DC generate significant amounts of IFN-β and that IFN-β is sequestered from the SN by the IFNAR in cocultures. We next tested the effect of the concentration of IFN-β added after infection on the control of HCMV in MRC-5 cells. We observed that IFN-β concentrations of up to 30 to 50 U/ml correlated with an improved protective effect at all MOIs tested, but further increases were ineffective (Fig. S3B).

FIG 4.

Blocking IFN-α/β receptor increases IFN-β availability in coculture medium yet does not negatively affect the antiviral function of mo-DC. (A) IFN-β concentration was measured by ELISA in coculture SNs from MRC-5 cells infected with 1,050 PFU of HCMVIEr (MOI of 0.035) and cocultured with or without mo-DC in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml anti-IFNAR2 for 14 days. Bars are representative of one of two independent experiments. (B) Infectious virus titers were measured in SNs from the experiment shown in panel A. Representative data from one of three independent experiments show means with standard deviations. (C) MRC-5 cells in eight-well replicates were infected with 150 PFU (MOI of 0.005) of HCMVIEr and cocultured with mo-DC in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml anti-IFNAR2, and the number of infection foci was quantified at 3 dpi. Data are from one of three independent experiments showing means with standard deviations. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Sidak's multiple-comparison test was used (ns, P ≥ 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (D) Representative images from the experiment shown in panel C at 8 dpi.

To test if the mo-DC suppress HCMV infection by releasing type I IFN, we used the anti-IFNAR2 antibody to block downstream IFNAR signaling (38). Cocultures of mo-DC and infected MRC-5 cells at E/T ratios of 20:1, 10:1, and 4:1 were treated with 10 μg/ml anti-IFNAR2 starting at 24 h before infection and maintained for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 4B). We observed the E/T ratio-dependent reduction of virus titers, and blocking of IFN type I signaling did not lead to the rescue of virus titers relative to those of untreated wells (Fig. 4B). If anything, IFNAR blocking consistently decreased the viral titer in the presence of mo-DC although this effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 4B). We considered the possibility that anti-IFNAR2 effects may be manifest at the gene expression level rather than at the PFU level. Therefore, we measured mNeonGreen expression upon infection with HCMVIEr in the presence of mo-DC and anti-IFNAR2. We observed no increase in the number of infected cells over the control levels in cocultures lacking anti-IFNAR2 (Fig. 4C), and they were not enlarged in the presence of anti-IFNAR2 (Fig. 4D). In fact, the foci appeared smaller in the presence of anti-IFNAR2, matching the PFU results (Fig. 4B). In sum, the evidence argued against a major role for type I IFN in the observed antiviral effect of mo-DC.

We considered the possibility that the IFNAR-2 blocking antibody might not be sufficiently efficient at blocking antiviral IFNAR effects in our assays. Therefore, we tested HCMVIEr replication in MRC-5 fibroblasts in the presence of IFN-β and IFNAR2 blocking antibodies (Fig. S4A). While IFN-β fully abrogated infectious virus titer if added before infection and significantly reduced the titer if added immediately postinfection, IFNAR2 blocking antibodies dampened this effect, increasing the virus titer (Fig. S4B). We also tested the effect of various concentrations and timings for anti-IFNAR2 as well as for IFN-β treatments (Fig. S4C). Data showed that anti-IFNAR2 could effectively block IFNAR signaling and thus block the antiviral effect of IFN-β that was added to infected cells just after the infection at concentrations up to 500 U/ml (Fig. S4C).

Since mo-DC produced comparable levels of IFN-β at E/T ratios of 4:1 and 20:1 (Fig. 4A), at which the antiviral effects were not identical (Fig. 2A), and since blocking IFNAR did not diminish the antiviral effect of mo-DC (Fig. 4B to D), our data argued that IFN signaling did not play a major role in the control of HCMV by mo-DC.

Antiviral factors from mo-DC stimulate antiviral defenses of target cells.

The antiviral action of mo-DC was mediated by soluble factors beyond type I IFN. We considered the possibility that the antiviral activity may occur by means of factors directly interacting with viral particles (39), viral gene products (40), or factors that elicit signaling pathways and activate cellular antiviral defenses of the target cells.

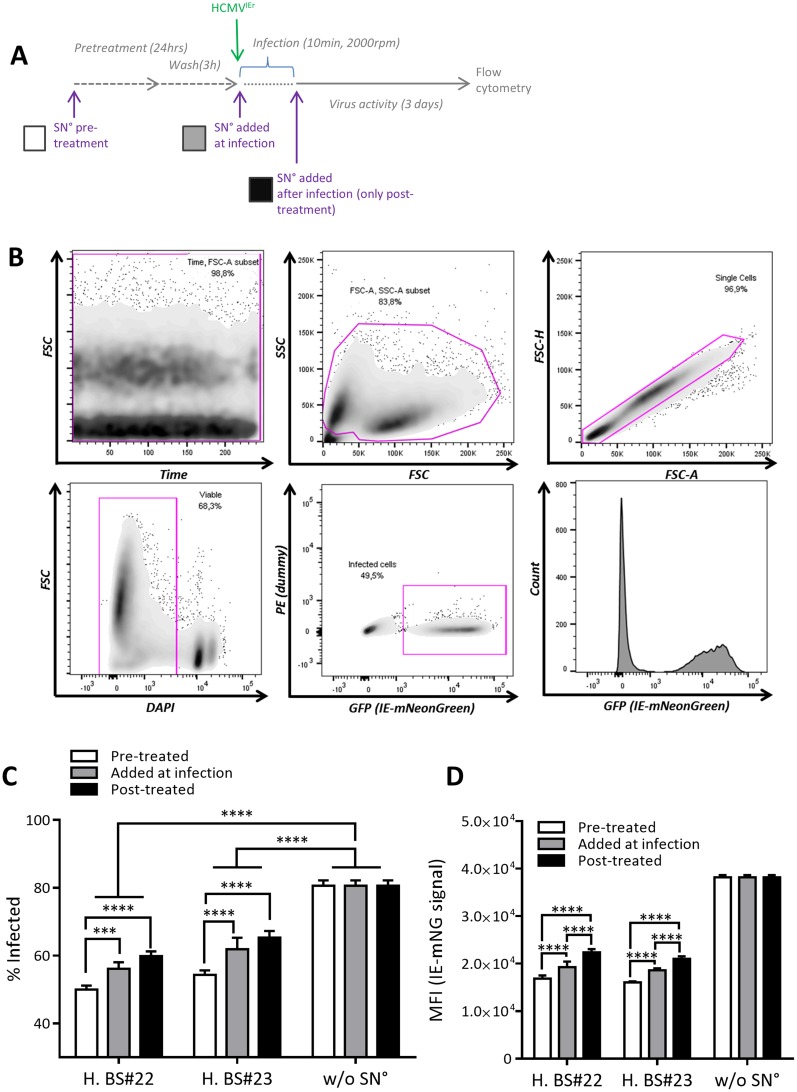

We tested these scenarios by additionally treating MRC-5 cells with the antiviral supernatant for 24 h before the infection or at the time of infection and comparing these cells to cells treated with SN° just after HCMVIEr infection (Fig. 5A). We measured the rate of infection and the mNeonGreen signal by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B). While the frequency of infected cells was reduced in all SN°-treated groups, pretreatment of cells with the SN° led to the most effective control of infection (Fig. 5C and S5B). Adding SN° only after infection was the least protective, and adding the SN° at the time of infection resulted in an intermediate antiviral effect. Similarly, SN° pretreatment reduced the reporter mean fluorescence signal intensity (MFI) more efficiently than SN° added at the time of infection or only after infection (Fig. 5D). Suppression of infection did not correlate significantly with loss of cell viability (Fig. 2B and C and S5A). Therefore, our data argued that the antiviral SN acts by inducing noncytotoxic antiviral signaling pathways in target cells.

FIG 5.

Pretreatment with the antiviral SN improves control of infection. (A) Antiviral SN°s from two donors (H. BS22 and H. BS23) were added to MRC-5 cells at 24 h before infection and then replaced with medium 21 h later (pretreatment; white bars). Synchronized infection of cells with HCMVIEr at an MOI of 0.035 in medium or SN° (added at infection; gray bars) was carried out, and SN° was added to all conditions after the virus was removed (posttreatment; black bars). (B) Gating strategy for flow cytometric analysis. Bars show the percentage of infected cells in four replicates (C) and the mean fluorescence intensity of the infected cells (D) for each condition. Regular two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons between all data sets was used in one representative of two independent experiments (***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001). FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter; H, height; A, area; H. BS, human blood sample.

Mo-DC are activated by contact with infected MRC-5 cells but not by direct infection.

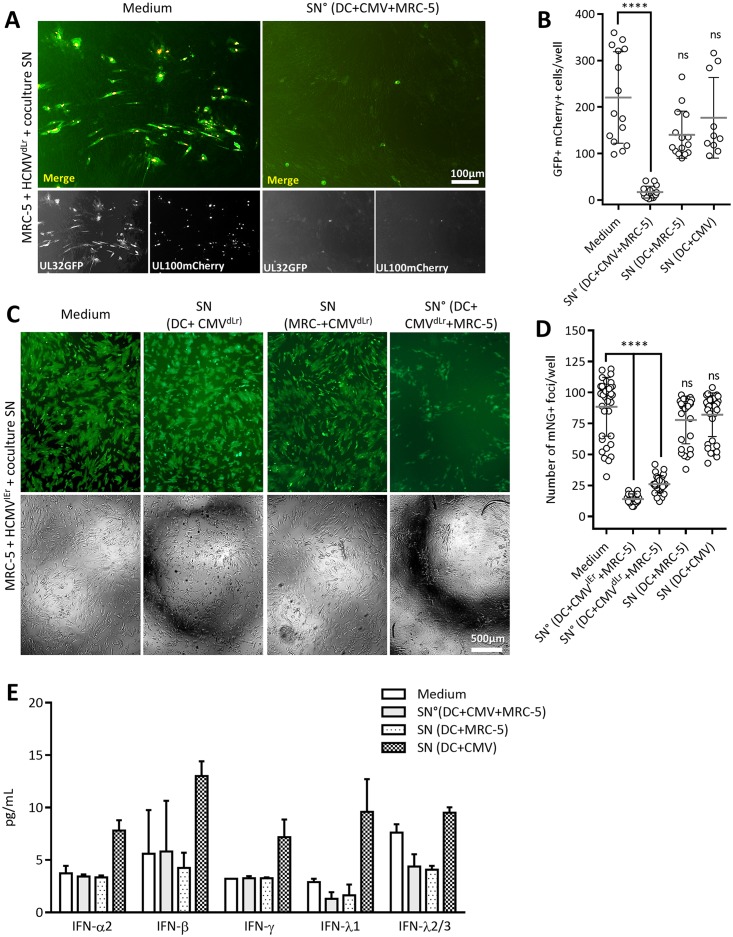

It remained unclear if the antiviral function of mo-DC was stimulated by simple contact with uninfected MRC-5 cells, by direct virus infection, or by contact with infected MRC-5 cells. Therefore, we compared the effects of conditioned SN from (i) infected mo-DC/MRC-5 cocultures, (ii) uninfected cocultures of DC and MRC-5 cells, or (iii) mo-DC infected with HCMV in the absence of MRC-5 cells. Conditioned SN was added to MRC-5 cells infected with the dual-late-reporter HCMVdLr, and their effect was defined by comparing the spread of infection at 5 to 6 dpi. Only the SNs from infected mo-DC/MRC-5 cocultures effectively suppressed HCMVdLr spread (Fig. 6A and B), whereas SNs from uninfected cocultures did not. Even more intriguingly, SN from mo-DC directly infected with HCMV in the absence of MRC-5 cells did not inhibit virus spread (Fig. 6B). We repeated the assay using the immediate early HCMVIEr reporter virus (Fig. 6C and D). As in the case of the late reporter virus, only the SN from infected cocultures reduced HCMVIEr spread (Fig. 6C and D), and it was irrelevant if HCMVIEr or HCMVdLr was used for the infection of the primary coculture. Similarly, SN from DC infected in the absence of MRC-5 or from uninfected DC/MRC-5 cocultures showed no antiviral effect. Finally, we tested the supernatants from different coculture and/or infection conditions for multiple IFNs, including IFN-α2, -β, -γ, -λ1, and -λ2/3. While we observed a clear induction of all IFN responses in HCMV-infected DC monocultures, none of them was induced in the case of the antiviral SN° derived from cocultures of infected MRC-5 and mo-DC (Fig. 6E).

FIG 6.

Mo-DC contact with infected MRC-5 cells is required for stimulation of mo-DC antiviral function and does not involve IFN. (A) Representative images at 5 dpi (A) and quantification at 5 to 6 dpi of the spread of infection HCMVdLr (MOI of 0.0125) (B) in MRC-5 cells treated, from left to right, with culture medium as a control, with SN of an mo-DC/MRC-5 coculture at an E/T ratio of 10:1 infected with HCMVdLr (MOI of 0.001) or uninfected, or with SN of a culture of 1 × 106 mo-DC infected at an MOI of 1 collected at 6 to 8 dpi (the experimental design is depicted in Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Data represent at least three independent experiments with mo-DC generated from six different PBMC donors, showing means with standard deviations. Representative images at 8 dpi (C) and quantification at 3 dpi of the spread of HCMVIEr (MOI of 0.005) infection (D) in cells treated as described for panel B. (E) Concentrations of IFN-α2, -β, -γ, -λ1, and -λ2/3 were measured in the SNs using a multianalyte flow assay (LEGENDplex), with n ≥ 9 samples for antiviral SN and n ≥ 3 for other conditions. Differences were not statistically significant. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunn's multiple-comparison test for each column against the control column (culture medium) was used (ns, P ≥ 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001).

Taken together, these data indicated that mo-DC-secreted antiviral factors repressing HCMV IE and late gene expression are independent of major type I to III interferons and are only induced by the interaction of mo-DC with infected MRC-5 cells, arguing that mo-DC possess sensors that recognize infected cells and trigger their activation.

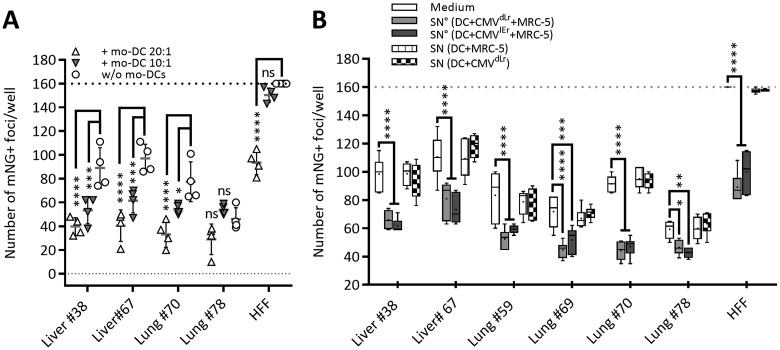

Antiviral function of mo-DC is maintained in primary target cells.

To test if mo-DC antiviral activity is restricted to the control of HCMV in the fibroblast cell line MRC-5 or if it acts broadly in primary HCMV permissive cells of different origins, we isolated primary stromal cells from human lung and liver tissue and used them in coculture experiments. These cells were primarily composed of fibroblast and endothelial cell types, and results were compared to those with primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) infected with HCMVIEr and cocultured with mo-DC (Fig. 7A). Mo-DC suppressed the spread of infection in an E/T ratio-dependent manner in most primary cell cultures, with a robust antiviral effect observed is some (Fig. 7A, Lung 38), although not all, lines (Fig. 7A, Lung 78). Antiviral SN from infected mo-DC/MRC-5 cocultures had a similar effect on HCMVIEr infection in primary cell cultures (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the antiviral effect of mo-DC was not exclusive to the MRC-5 cell line and is likely to act on a wide variety of cell types. Taken together, our data show that soluble factors secreted from human mo-DC are able to repress HCMV gene expression and suppress the spread of infection in a variety of target cells independently of IFN-β.

FIG 7.

Mo-DC cocultures and their coculture supernatants suppress HCMV spread in primary human cells. Primary human cells were infected with 300 PFU (MOI of 0.01) and cocultured with mo-DC (A); alternatively, SNs were added to the infected cells, and the spread of infection was quantified at 5 dpi (B) (as described in the legend of Fig. 6). Combined data from two independent experiments showing means with standard deviations are shown. Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test was used (ns, P ≥ 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have demonstrated the ability of CMV to infect and establish latency in monocytes and DC derived from them (21, 26, 41–43), but these studies were customarily focused on the study of mo-DC behavior in monocultures. We showed recently a role for DC in controlling CMV infection in nearby cells in a murine model, where in vitro-infected fibroblasts or endothelial cells were cocultured with mDC (22). We expand on the findings from that report and show that human mo-DC are activated by HCMV-infected fibroblasts in a manner that functionally differs from direct infection of mo-DC in monocultures. While the identity of this trigger at the molecular level goes beyond the scope of this study, its broader implication is that, in addition to recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns, mo-DC may also detect nearby infected cells and likely engage in receptor/ligand interactions with them. In this report, we provide evidence of this novel immune sensing mechanism.

We partly identified the mechanism of antiviral action of mo-DC; we demonstrate that HCMV is contained by soluble factors released in mo-DC/fibroblast cocultures and that these factors already act during or before immediate early gene expression. While viral repression was even stronger at later stages of the viral replication cycle, one needs to consider that any cumulative antiviral effects would result in a more profound repression of the virus at later stages. Importantly, the antiviral effects were stronger if the target cells were pretreated with the conditioned supernatants, arguing against direct virus inactivation (39). Therefore, our data may be consistent with a model where factors released by mo-DC induce antiviral effector pathways in the target cells.

Based on our data from the murine model, we considered type I IFN signaling to be a likely candidate for driving the antiviral effect, but assays with the IFNAR-blocking antibody argue against this scenario. On the other hand, data from the murine system did not exclude the possibility that IFN signaling requires synergizing with additional factors to control MCMV (22). Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the antiviral action of human mo-DC partially overlaps with the mechanisms in murine cocultures. Both murine and human DC blocked viral gene expression at the immediate early stage, and viral gene expression was reconstituted upon mo-DC removal from cocultures, resembling reactivation phenotypes in HCMV models of in vitro latency (42, 44, 45). Since the balance of virus latency appears to hinge on cell signaling (46) and may be influenced via cellular inflammatory cytokines (41, 47), our data raise the possibility that factors released by myeloid cells or by their precursors may actively regulate viral gene expression and replication, balancing HCMV latency and reactivation. Considering that all currently studied in vitro models of HCMV latency are based on the infection of monocytes or their precursors, our data raise the intriguing possibility that at least part of this phenomenon is due to autocrine or paracrine factors released by myeloid cells (47).

We used a novel HCMV reporter virus in this study, in which a fluorescence reporter gene was expressed by the endogenous major immediate early promoter. Live-cell imaging of cells infected with this virus allowed us to show that mo-DC delay immediate early gene expression although they do not entirely abrogate its expression. Future research will focus on the identification of the soluble factors critical for HCMV control at this stage in order to appraise the feasibility of their utilization for treatment of HCMV infection and disease. By developing the in vitro model of mo-DC/fibroblast coculture, we have opened the doors toward such approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human embryonic lung fibroblast MRC-5 cells (ATCC CCL171) were maintained in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM) (M5650; Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Human monocyte-derived DC (mo-DC) were generated and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Human primary stromal liver and lung cells were isolated from donated liver tissue biopsy samples and explanted lung tissue of transplant recipients from the Hannover Medical School, as described elsewhere (48, 49), and maintained in EGM-2MV primary endothelial medium (Lonza). Primary human foreskin fibroblasts were cultivated in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (D5796; Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Generation of human monocyte-derived DC.

PBMCs were isolated from leukoreduction system (LRS) filter chambers used in apheresis machines of the Institute for Transfusion Medicine of the Hannover Medical School (MHH) as described before (50) within 18 h after the donation by healthy individuals using Lymphoprep (Stemcell Technologies, Canada) density gradient centrifugation (51). Mo-DC were generated by two methods, conventional and rapid.

(i) Conventional mo-DC generation protocol.

As described previously (32), monocytes were either separated from the rest of PBMCs via two subsequent rounds of plastic adherence in serum-free RPMI medium (52) or magnetically sorted (MACS) using anti-CD14 microbeads (human CD14+ microbeads and an AutoMACS Pro separator; Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) and cultivated at 2 × 106 cells/ml in full RPMI medium with 800 U/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Peprotech, USA) and 500 U/ml IL-4 (Peprotech, USA) for 5 days, after which they were transferred to full fresh RPMI medium containing GM-CSF, IL-4, and 100 U/ml tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; R&D Systems, USA) for an additional 3 to 5 days of maturation. Mature conventionally generated mo-DC were then thoroughly washed and pelleted three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and used in experiments within 6 h.

(ii) Rapid mo-DC generation protocol.

As previously shown (34, 53, 54), MACS-sorted CD14+ monocytes were cultivated at 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/ml in full RPMI medium in the presence of a differentiation cocktail containing 200 to 500 U/ml GM-CSF, 50 to 200 U/ml IL-4, and 1,000 U/ml IFN-β for 36 to 48 h. Thereupon, 200 U/ml TNF-α (Peprotech, USA), 5,000 to 1,000 U/ml IL-1β (Peprotech, USA), and 1 μg/ml prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; Biolegend, Germany) were added for an additional 2 to 3 days to induce DC maturation.

Viruses.

In the dual-reporter HCMV strain TB40/E-UL32-GFP/UL100-mCherry, enhanced GFP (EGFP) and mCherry are fused to the C terminus of the late-phase capsid-associated tegument protein pUL32 (pp150) and the envelope glycoprotein M (UL100), respectively, expressing readily detectable green and red fluorescence signals in lytically infected host cells, as described elsewhere (33). Reporter HCMV strain HCMV TB40/E-UL122/123-mNeonGreen was generated using en passant bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) mutagenesis (55) on a TB40/E-BAC background (GenBank accession number EF999921) as described elsewhere (56), with the difference that the unique short (US) region of the BAC is inverted relative to that of the original BAC. The mNeonGreen (mNG) gene, coding a novel bright green fluorescent protein (Allele Biotech, USA) (35), linked to the P2A peptide (57) was inserted before the start codon of UL122/123 exon 2 (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). The endogenous HCMV major immediate early (MIE) promoter drives mNG-P2A expression in an equimolar ratio with the products of MIE genes UL123 (IE1) and UL122 (IE2). Ribosomal skipping between glycine 21 and proline 22 of P2A peptide causes efficient cleavage at this position, separating mNG with a 23-amino-acid (aa)-long fragment, comprised of two linker amino acids plus 21 aa of the P2A, on its C terminus while leaving one proline from P2A at the N terminus of exon 2 of MIE gene products, thus effectively minimizing the risk of interference with the function of viral proteins compared to that of an approach using a fusion protein. The reporter insertion and final BAC sequence were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The reporter virus has growth kinetics identical to those of its parental virus (Fig. S2B).

Coculture with the monocyte-derived dendritic cells, mo-DC.

Immediately after the virus suspension was removed, monocyte-derived dendritic cells, harvested from maturation within 6 h of the start of the experiment, were added to infected target cells at defined effector-to-target (E/T) ratios in 200 μl of full medium (based on target cells) per well in 3- to 12-well replicates. A schematic outline is depicted in Fig. S1A.

Generation and processing of antiviral coculture supernatant.

Mo-DC were added to uninfected or HCMV-infected (MOI of 0.01; 2 h) MRC-5 cells at an E/T ratio of 10:1, or mo-DC were left uninfected or infected for 2 h with HCMV at an MOI of 1.0 in wells of a six-well plate or 3.5-cm culture dish containing 5 ml of full RPMI medium. After 6 to 8 days, the well content was collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 700 × g at 4°C to remove cells and debris, filtered through a 0.1-μm-pore-size syringe-mounted filter, aliquoted, and frozen at −20°C until use. A schematic outline is depicted in Fig. S1B.

Virus titration.

The titer of cell-free virus in well supernatant was quantified by plaque assay. At the readout time point, the SN was removed and frozen at −80°C before use. One hundred microliters of SN was serially diluted in full EMEM and added to 30,000 fresh MRC-5 cells seeded 1 day in advance for 2 h of incubation. The virus suspension was removed, and cells were overlaid with EMEM containing 5% carboxymethylcellulose. After 5 to 8 days of incubation, virus plaques were counted, and the virus titer is reported as the number of PFU per milliliter of SN.

Infection and quantification by microscopy.

The human embryonic fibroblast-like cell line MRC-5 or human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were seeded at 25,000 cells/well in flat-bottom 96-well plates 1 day before infection. Human primary stromal cells from lung and liver were seeded in numbers to reach 30,000 on the day of infection on 0.2% gelatin (in PBS solution)-coated plates. For infection, virus was added in a 100-μl suspension at a defined multiplicity of infection (MOI) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h before the virus suspension was removed. When the TB40/E-UL32-GFP/UL100-mCherry dual-late-gene reporter virus (HCMVdLr) was used, infected single cells expressing both the green EGFP and the red mCherry fluorescence signals were counted at 5 to 6 dpi unless stated otherwise. When the TB40/E-UL122/123-mNeonGreen immediate early reporter virus (HCMVIEr) was used, mNeonGreen-expressing infection foci (group of several infected cells that do not yet show clearly observable cytopathic effect [CPE]) were visible already by day 2. The foci were quantified at days 2 to 3 before the merging of growing adjacent foci or the spread of secondary infection would affect the readout (Fig. S1A). Alternatively, a centrifugal enhancement protocol of infection was used when synchronous infection of target cells was required. A virus suspension in 100 μl per well was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature essentially as described elsewhere (36). This protocol increased the rate of infection by a factor of 3 to 5 compared to the level with the method using 2 h of incubation, and therefore MOIs for these were based on centrifugally enhanced virus titration.

Live-cell imaging and quantification.

MRC-5 fibroblasts were seeded at 75,000 cells/chamber on glass-bottom live-cell imaging dishes (Hi-Q4; ibidi) and infected at an MOI of 0.035 by the centrifugal method, followed by removal of the virus suspension. A BioStation IM-Q live-cell screening system (Nikon, Japan) with a complete environmental incubation system was used to follow the infection for up to 8 days. Images were acquired from up to 24 fields per condition at a magnification of ×20 with 1,024 by 940 pixels in bright-field, GFP, and Texas Red channels, when applicable, at 12% illumination intensity, a 500-ms exposure, and 5.6 gain settings for fluorescence channels and acquisition rates of one image every 20 to 60 min. Time series stacks for all fields were analyzed automatically using an in-house Fiji (ImageJ) (58) macro (see the supplemental Materials and Methods and Fig. S6). Briefly, the bright IE-mNeonGreen signal was used to detect infected cells and then to measure and report the mean fluorescence signal intensity for infected cells and the background in each frame in the GFP (for mNeonGreen) channel of the BioStation IM-Q. The mean signal from all cells in a frame was divided by the mean background signal (i.e., signal ratio) in order to compensate for random signal fluctuations as well as field-to-field and experiment-to-experiment variations (Fig. 5G and Movie S1) and was plotted in GraphPad Prism. Onset time was defined as the time point of the first frame after which the signal ratio steadily increased in every subsequent frame (i.e., point of true deviation from asymptote) and was analyzed manually.

Blocking of type I interferon signaling.

Antibody against the human interferon (alpha, beta, and omega) receptor 2 (IFNAR2) (21385-1, clone MMHAR-2; PBL Assay Science, USA) was used to block the IFNAR2 subunit of the common IFN type I receptor and neutralize IFN type I signaling. Depending on the experimental conditions, cells were treated for up to 24 h before infection with up to 20 μg/ml of anti-IFNAR2 antibody. After infection, anti-IFNAR2 was again added to cells at up to 20 μg/ml. In longer experiments, fresh antibody was added to the wells at half of the original concentration every 7 days.

IFN ELISA and multiplex assay.

An IFN ELISA and multiplex assay were performed using a human IFN-β ELISA kit, high-sensitivity serum, plasma, tissue culture medium (TCM) (41415-1; PBL Assay Science, USA), and a LEGENDplex human antivirus response panel (740390; BioLegend, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The nominal limit of detection for the ELISA was 0.39 U/ml (1.17 pg/ml).

Flow cytometric analysis of infection.

Infected cells were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before trypsinization for 1 min at 1:1,000 in PBS solution in 100 μl per well, thoroughly washed, and trypsinized. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (120 μl) was added to each well, and cells were thoroughly resuspended and analyzed with a BD LSRII SORP flow cytometer equipped with a high-throughput sampler (HTS).

Statistical analysis.

Appropriate statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism software, based on the data and plot type as stated in figure legends. Where multiple conditions were compared to a control condition (Fig. 1, 2, 6, and S3A), analysis of variance (ANOVA) of group means was used as a nonparametric (non-Gaussian distribution) test (Kruskal-Wallis) with multiple comparisons against the mean rank of the common control group (Dunn's test) or in grouped data (Fig. 7) against the control in that group (Dunnett's test). Where multiple conditions were tested against each other (Fig. S4B), ordinary one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons was used. Where a single condition was compared to a single control (Fig. 3C), an unpaired nonparametric t test (Mann-Whitney) was used. Where a single condition was compared to a control within grouped data, two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons of means (Sidak's test) (Fig. 4C) or Tukey's test was used (Fig. 5C). All conditions within the same group were compared using Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (Fig. S4C).

Ethics statements.

Nonparenchymal human liver cells were supplied by the Clinic for General, Abdominal and Transplant Surgery, Hannover Medical School (MHH), under ethical permit number 2188-2014 from the MHH ethics commission. Human lung tissue samples were supplied by the Department of Cardiothoracic, Transplantation and Vascular Surgery, MHH, under ethical permit number 7191 from the MHH ethics commission. Leukoreduction system (LRS) chambers for PBMC isolation were supplied by the Institute for Transfusion Medicine, MHH, under ethical permit 2519-2014 from the MHH ethics commission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christian Sinzger and Kerstin Laib Sampaio for generously providing us with the TB40/E-UL32-GFP/UL100-mCherry reporter virus and Harald Wodrich for providing us with primary human foreskin fibroblasts. In addition, we thank Julia Holzki and Zeeshan Chaudhry for ideas and discussions, Ayse Barut and Ilona Bretag for their help in preparation of donated PBMCs and primary cells, and Johannes Greiner for help in setting up some experiments.

This work was supported by the German Scientific foundation (DFG) through grant SFB900 TP-B2 and through Infect-ERA grant eDEVILLI to L.C.-S.

The funding agency had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or in the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01138-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boppana SB, Fowler KB. 2007. HCMV: persistence in the population: epidemiology and transmission, p 795–813. In Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume C, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizamn B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K (ed), Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Söderberg-Nauclér C, Nelson JA. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation–a delicate balance between the virus and its host's immune system. Intervirology 42:314–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sissons JGP, Bain M, Wills MR. 2002. Latency and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus. J Infect 44:73–77. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legendre C, Pascual M. 2008. Improving outcomes for solid-organ transplant recipients at risk from cytomegalovirus infection: late-onset disease and indirect consequences. Clin Infect Dis 46:732–740. doi: 10.1086/527397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, Sleath PR, Grabstein KH, Hosken NA, Kern F, Nelson JA, Picker LJ. 2005. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med 202:673–685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lathbury LJ, Allan JE, Shellam GR, Scalzo AA. 1996. Effect of host genotype in determining the relative roles of natural killer cells and T cells in mediating protection against murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Gen Virol 77:2605–2613. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-10-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miletić A, Krmpotić A, Jonjić S. 2013. The evolutionary arms race between NK cells and viruses: who gets the short end of the stick? Eur J Immunol 43:867–877. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collin M, McGovern N, Haniffa M. 2013. Human dendritic cell subsets. Immunology 140:22–30. doi: 10.1111/imm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romani N, Gruner S, Brang D, Kämpgen E. 1994. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J Exp Med 180:83–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahn G, Stenglein S, Riegler S, Einsele H, Sinzger C. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus infection of immature dendritic cells and macrophages. Intervirology 42:365–372. doi: 10.1159/000053973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riegler S, Hebart H, Einsele H, Brossart P, Jahn G, Sinzger C. 2000. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells are permissive to the complete replicative cycle of human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol 81:393–399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck K, Meyer-König U, Weidmann M. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus impairs dendritic cell function: a novel mechanism of human cytomegalovirus immune escape. Eur J Immunol 33:1528–1538. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves MB, Sinclair JH. 2013. Circulating dendritic cells isolated from healthy seropositive donors are sites of human cytomegalovirus reactivation in vivo. J Virol 87:10660–10667. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01539-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renneson J, Dutta B, Goriely S, Danis B. 2009. IL-12 and type I IFN response of neonatal myeloid DC to human CMV infection. Eur J Immunol 39:2789–2799. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paijo J, Doring M, Spanier J, Grabski E, Nooruzzaman M, Schmidt T, Witte G, Messerle M, Hornung V, Kaever V, Kalinke U. 2016. cGAS senses human cytomegalovirus and induces type I interferon responses in human monocyte-derived cells. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005546. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raftery MJ, Schwab M, Eibert SM, Samstag Y. 2001. Targeting the function of mature dendritic cells by human cytomegalovirus: a multilayered viral defense strategy. Immunity 15:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins C, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2004. A novel viral transcript with homology to human interleukin-10 is expressed during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 78:1440–1447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1440-1447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang WLW, Barry PA, Szubin R, Wang D. 2009. Human cytomegalovirus suppresses type I interferon secretion by plasmacytoid dendritic cells through its interleukin 10 homolog. Virology 390:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avdic S, McSharry BP, Slobedman B. 2014. Modulation of dendritic cell functions by viral IL-10 encoded by human cytomegalovirus. Front Microbiol 5:337. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexandre YO, Cocita CD, Ghilas S, Dalod M. 2014. Deciphering the role of DC subsets in MCMV infection to better understand immune protection against viral infections. Front Microbiol 5:378. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benedict CA, Loewendorf A, Garcia Z. 2008. Dendritic cell programming by cytomegalovirus stunts naive T cell responses via the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway. J Immunol 180:4836–4847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holzki J, Dăg F, Dekhtiarenko I, Rand U, Casalegno-Garduño R, Trittel S, May T, Riese P, Čičin-Šain L. 2015. Type I interferon released by myeloid dendritic cells reversibly impairs cytomegalovirus replication by inhibiting immediate early gene expression. J Virol 89:9886–9895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01459-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streblow DN, Varnum SM, Smith RD, Nelson JA. 2006. A proteomics analysis of human cytomegalovirus particles, p 91–110. In Reddehase MJ. (ed), Cytomegaloviruses: molecular biology and immunology. Caister Academic Press, Wymondham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Q, Maul GG. 2006. Mouse cytomegalovirus crosses the species barrier with help from a few human cytomegalovirus proteins. J Virol 80:7510–7521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00684-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawlinson WD, Farrell HE, Barrell BG. 1996. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 70:8833–8849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheu S, Dresing P, Locksley RM. 2008. Visualization of IFNβ production by plasmacytoid versus conventional dendritic cells under specific stimulation conditions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:20416–20421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808537105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puttur F, Francozo M, Solmaz G, Bueno C. 2016. Conventional dendritic cells confer protection against mouse cytomegalovirus infection via TLR9 and MyD88 signaling. Cell Rep 17:1113–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doring M, Lessin I, Frenz T, Spanier J, Kessler A, Tegtmeyer P, Dag F, Thiel N, Trilling M, Lienenklaus S, Weiss S, Scheu S, Messerle M, Cicin-Sain L, Hengel H, Kalinke U. 2014. M27 expressed by cytomegalovirus counteracts effective type I interferon induction of myeloid cells but not of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Virol 88:13638–13650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00216-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyznik AJ, Verma S, Wang Q, Kronenberg M, Benedict CA. 2014. Distinct requirements for activation of NKT and NK cells during viral infection. J Immunol 192:3676–3685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swiecki M, Gilfillan S, Vermi W, Wang Y, Colonna M. 2010. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell ablation impacts early interferon responses and antiviral NK and CD8+ T cell accrual. Immunity 33:955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair S, Archer GE, Tedder TF. 2012. Isolation and generation of human dendritic cells. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 7:Unit 7.32. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0732s23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampaio KL, Jahn G, Sinzger C. 2013. Applications for a dual fluorescent human cytomegalovirus in the analysis of viral entry. Methods Mol Biol 1064:201–209. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-601-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodama A, Tanaka R, Saito M, Ansari AA, Tanaka Y. 2013. A novel and simple method for generation of human dendritic cells from unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cells within 2 days: its application for induction of HIV-1-reactive CD4+ T cells in the hu-PBL SCID mice. Front Microbiol 4:292. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaner NC, Lambert GG, Chammas A, Ni Y, Cranfill PJ, Baird MA, Sell BR, Allen JR, Day RN, Israelsson M, Davidson MW, Wang J. 2013. A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat Methods 10:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osborn JE, Walker DL. 1968. Enhancement of infectivity of murine cytomegalovirus in vitro by centrifugal inoculation. J Virol 2:853–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pascutti MF, Rodriguez AM, Falivene J, Giavedoni L, Drexler I, Gherardi MM. 2011. Interplay between modified vaccinia virus Ankara and dendritic cells: phenotypic and functional maturation of bystander dendritic cells. J Virol 85:5532–5545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02267-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domanski P, Witte M, Kellum M, Rubinstein M, Hackett R, Pitha P, Colamonici OR. 1995. Cloning and expression of a long form of the subunit of the interferon receptor that is required for signaling. J Biol Chem 270:21606–21611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stegmann C, Hochdorfer D, Lieber D, Subramanian N, Stohr D, Laib Sampaio K, Sinzger C. 2017. A derivative of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha binds to the trimer of human cytomegalovirus and inhibits entry into fibroblasts and endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006273. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiaofei E, Stadler BM, Debatis M, Wang S, Lu S, Kowalik TF. 2012. RNA interference-mediated targeting of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early or early gene products inhibits viral replication with differential effects on cellular functions. J Virol 86:5660–5673. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06338-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hahn G, Jores R, Mocarski ES. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:3937–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reeves MB, Lehner PJ. 2005. An in vitro model for the regulation of human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation in dendritic cells by chromatin remodelling. J Gen Virol 86:2949–2954. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson SE, Sedikides GX, Mason GM, Okecha G, Wills MR. 2017. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-specific CD4+ T cells are polyfunctional and can respond to HCMV-infected dendritic cells in vitro. J Virol 91:e02128-. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02128-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodrum F, Reeves M, Sinclair J, High K, Shenk T. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus sequences expressed in latently infected individuals promote a latent infection in vitro. Blood 110:937–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung AK, Abendroth A, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B. 2006. Viral gene expression during the establishment of human cytomegalovirus latent infection in myeloid progenitor cells. Blood 108:3691–3699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-026682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buehler J, Zeltzer S, Reitsma J, Petrucelli A, Umashankar M, Rak M, Zagallo P, Schroeder J, Terhune S, Goodrum F. 2016. Opposing regulation of the EGF receptor: a molecular switch controlling cytomegalovirus latency and replication. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005655. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reeves MB, Compton T. 2011. Inhibition of inflammatory interleukin-6 activity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling antagonizes human cytomegalovirus reactivation from dendritic cells. J Virol 85:12750–12758. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05878-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Beijnum JR, Rousch M, Castermans K, van der Linden E, Griffioen AW. 2008. Isolation of endothelial cells from fresh tissues. Nat Protoc 3:1085–1091. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujino N, Kubo H, Ota C, Suzuki T, Suzuki S, Yamada M, Takahashi T, He M, Suzuki T, Kondo T, Yamaya M. 2012. A novel method for isolating individual cellular components from the adult human distal lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46:422–430. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietz AB, Bulur PA, Emery RL, Winters JL, Epps DE, Zubair AC, Vuk-Pavlović S. 2006. A novel source of viable peripheral blood mononuclear cells from leukoreduction system chambers. Transfusion 46:2083–2089. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuss IJ, Kanof ME, Smith PD, Zola H. 2009. Isolation of whole mononuclear cells from peripheral blood and cord blood. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 7:Unit 7.1. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0701s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wahl LM, Smith PD. 2001. Isolation of monocyte/macrophage populations. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 7:Unit 7.6. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0706s16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obermaier B, Dauer M, Herten J, Schad K, Endres S, Eigler A. 2003. Development of a new protocol for 2-day generation of mature dendritic cells from human monocytes. Biol Proced Online 5:197–203. doi: 10.1251/bpo62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dauer M, Obermaier B, Herten J, Haerle C, Pohl K, Rothenfusser S, Schnurr M, Endres S, Eigler A. 2003. Mature dendritic cells derived from human monocytes within 48 hours: a novel strategy for dendritic cell differentiation from blood precursors. J Immunol 170:4069–4076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tischer BK, Smith GA, Osterrieder N. 2010. En passant mutagenesis: a two step markerless red recombination system. Methods Mol Biol 634:421–430. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-652-8_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sinzger C, Hahn G, Digel M. 2008. Cloning and sequencing of a highly productive, endotheliotropic virus strain derived from human cytomegalovirus TB40/E. J Gen Virol 89:359–368. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim JH, Lee S-RR, Li L-HH, Park H-JJ, Park J-HH, Lee KY, Kim M-KK, Shin BA, Choi S-YY. 2011. High cleavage efficiency of a 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1 in human cell lines, zebrafish and mice. PLoS One 6:e18556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.