Abstract

Context:

In recent days, we have come across an increase incidence of dry mouth as a side effects of drugs and in order to bring an awareness about a simple non- invasive method to increase the salivary flow, we have used TENS which in many way is beneficial to patients with metabolic disorders.

Aims and Objectives:

The aim is to assess the effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on salivary gland function in patients with hyposalivation.

Subjects and Methods:

The present study included total of 25 subjects with complaint of hyposalivation. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Subjects with pacemakers, autoimmune diseases, pregnancy, and history of salivary gland pathology were excluded from the study. Subjects were asked to refrain from eating, drinking, chewing gum, smoking, and oral hygiene procedures for at least 1 h before the appointment. Unstimulated saliva was collected using modified Carlson Crittenden cup placed over the Stenson's duct bilaterally for 5 min and measured. TENS pads were placed over the parotid region and were activated. The intensity control switch was adjusted for patient's comfort. The intensity was turned up 1 increment at a time at 5 s intervals until the optimal intensity level was reached and stimulated saliva was then collected for 5 min using the modified Carlson Crittenden cup and measured. Any increase in parotid salivary flow (SF) with electrostimulation was considered a positive finding.

Statistical Analysis Used:

A paired t-test, evaluating mean changes in stimulated versus unstimulated SF rates, was applied to look for statistically significant differences using PASW 18.0 for Windows. An independent sample t-test was performed to note difference between genders.

Results:

There was significant increase in parotid SF in 19 of 25 patients after transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Males showed more salivary secretion when compared to females.

Conclusions:

From the results of the study and within limitations of the study, it can be concluded that TENS was effective in increasing the SF rate in hyposalivatory patients with residual saliva. TENS was less effective in patients who are under xerogenic drugs. Thus, TENS may be an ever-growing armamentarium in the management of salivary gland hypofunction when other therapies have failed or are contraindicated.

Keywords: Hyposalivation, saliva, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, xerostomia

INTRODUCTION

Saliva is a clear, slightly acidic mucoserous exocrine secretion. The major salivary glands include the paired parotid glands, the submandibular and sublingual glands.[1] Minor glands that produce saliva are found in the lower lip, tongue, antero-lateral parts of palate, cheeks, and pharynx. Stimulated high flow rates drastically change percentage contributions from each gland, with the parotid contributing more than 50% of total salivary secretions. A healthy person's mean daily saliva production ranges from 1 to 1.5 L.[2] The salivary flow (SF) index is a parameter allowing stimulated and unstimulated saliva flow to be classified as normal, low, or very low (hyposalivation). The normal unstimulated SF ranges from 0.25 to 0.35 mL/min whereas low ranges from 0.1 to 0.25 mL/min, while hyposalivation is characterized by a SF of <0.1 mL/min. In adults, normal total stimulated SF ranges from 1 to 3 mL/min and low ranges from 0.7-1.0 mL/min. Hyposalivation is characterized by a SF of <0.7 mL/min. The normal unstimulated parotid SF ranges from 0.05-0.07 mL/min. The mean stimulated parotid flow rates in adult males is 0.59 mL/min ± 0.06 and for adult females is 0.45 mL/min ± 0.04.[2] Sialometry is a measurement of salivary secretion, generally for a comparison of a denervated or diseased gland with its healthy counterpart. Sialometry can be used as a diagnostic tool mainly in two ways: Collection of whole saliva—that is, combined secretions of all salivary glands—and collection of glandular saliva—that is, gland specific saliva.

Several factors may influence SF and its composition which include individual hydration, body posture, lighting conditions, smoking, thinking of food or looking at food, size of the salivary gland, physical activities, alcohol, medications, systemic diseases, nutrition, fasting, nausea, anxiety, age, and gender.[2] Medications are the most common cause of decreased salivary function. It has been reported that 80% of the most commonly prescribed medications cause xerostomia.[3]

Functional diseases of saliva include sialorrhea, drooling, and xerostomia. Xerostomia is the subjective sensation of dry mouth, whereas hyposalivation is the objective finding of a reduced SF rate.[4] Patients with low SF may experience many problems which include: xerostomia; an increase in caries; reduced clearance of bacteria and food, leading to mucosal soreness, gingivitis, cheilitis, fissuring of the tongue, and infection of the salivary ducts; difficulty in chewing, speaking, and swallowing; increased frequency of calculus deposition in the salivary ducts; burning mouth, and difficulty in retention of dentures. TENS could have stimulated the auriculotemporal nerve which is the secretomotor nerve to the parotid gland. TENS units was effective in increasing parotid SF in two-thirds of healthy adult subjects. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of TENS on parotid SF in hyposalivatory patients.

Aims and Objectives

The aim is to assess the effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on salivary gland function in patients with hyposalivation.

To assess the increase in salivary flow in patients with dry mouth using TENS in right parotid gland.

To Assess the Increase in Salivary Flow in Patients With Dry Mouth Using Tens in Left Parotid Gland.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee, Rajah Muthiah Dental College and Hospital, Annamalai University. Twenty-five patients with complaint of dry mouth were included, (14 males and 11 females) with written informed consent obtained from them. Patient's (Oh DJ et al. 2008) demographic, social information, medical history, and details of adverse habits were obtained.

Exclusion criteria included patients <18 years of age and those with pacemakers, autoimmune disease, pregnancy, history of irradiation, and salivary gland pathology. Patients were asked to refrain from eating, drinking, chewing gum, smoking, and oral hygiene procedures an hour before the appointment. The materials used in this study Tens unit, Modified Carlson-Crittenden cup, 5 ml syringe, Dispovan, Micro balance, Borosil graduated test tubes, Stop Watch, Mouth mirror, Gloves, Face mask, Cotton, Dettol liquid soap.

The TENS unit employed was TX – 3T TENS ST-601 TM (Skylark Devices and Systems Co Ltd, Taiwan) [Figure 1]. The settings of the TENS unit were as follows: the pulse rate was fixed at 25 Hz, and the unit was in normal mode. The electrode pads were placed externally on the skin overlying the parotid glands with the TENS unit in off position.

Figure 1.

The electrode pads were placed externally on the skin overlying the parotid glands with the TENS unit in off position

A modified Carlson-Crittenden saliva collection cup was placed over Stensen's duct bilaterally [Figure 2]. The tube from the outer chamber was connected to a syringe and the tube from the inner chamber (saliva collection chamber) was connected to the test tube with markings from 0 ml to 15 ml.

Figure 2.

A modified Carlson-Crittenden saliva collection cup was placed over Stensen's duct

Unstimulated saliva was collected for 5 min in a preweighed test tubes. The TENS unit was activated and the intensity was turned up 1 increment at a time at 5-s intervals until an optimal intensity was reached. Stimulated saliva was then collected for 5 min into separate preweighed test tubes. Per individual subject, any increase in SF with electrostimulation was considered a positive finding.

A paired t-test, evaluating mean changes in stimulated versus unstimulated SF rates, was applied to look for statistically significant differences using PASW 18.0 for windows. An independent sample t-test was performed to note difference between genders.

RESULTS

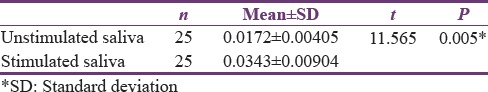

Nineteen of twenty-five subjects showed significant increase in parotid SF after the stimulation with TENS. The mean SF rate of unstimulated subjects was 0.0172 ± 0.00405 mL/min and the mean SF after TENS stimulation 0.0343 ± 0.00904 mL/min.

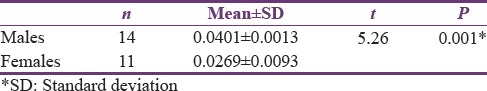

Statistical analysis with paired t-test showed the difference between the stimulated and unstimulated to be significant with P < 0.001 [Table 1]. Males demonstrated significantly more stimulated SF rate than females (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Comparison of unstimulated and stimulated saliva flow rate

Table 2.

Mean salivary flow rate of males and females

There were no adverse events or long-term side effects to use of the TENS. Only five subjects experienced facial muscle twitching during the procedure, but ceased immediately after the intensity was reduced.

DISCUSSION

Hyposalivation represents reduced saliva; xerostomia is a subjective sensation, and this differs depending on who provides the answer.[5] Patients with reduced SF may experience many problems including dry mouth.[4] Hence, the normal SF is considered to be critical for the maintenance of oral homeostasis and healthy oral mucosa.

The early diagnosis of salivary gland hypofunction is essential because it may be associated with undiagnosed systemic diseases and an increased risk of oro dental diseases. In the present study, we adapted this questionnaire in diagnosing the patients with reduced SF.

The methodology used in the present study is similar to the methodology used by Hargitai et al.[6] For treating patients with decreased SF many treatment procedures have been proposed such as secretogogues, chewing gum bases, citric lozenges, artificial saliva, etc., The secretogogues include pilocarpine and cevimeline, which have been reported effective in reliving dry mouth, they also have side effects such as blurred vision, sweating, and flushing, urinary incontinence and gastro intestinal discomfort. These drugs are contraindicated in patients with significant cardiovascular disease, Parkinson's disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[7] Even though many commercial saliva substitutes are available many did not fulfill all criteria such as no adverse effects, ease of use, and sufficient duration of action.[8]

Electrostimulation had been tried out and it showed promising results.[9] Advantage of TENS over previous modalities of electrostimulation is that it is an extra oral device. Thus, the potential for salivary production while eating would be beneficial. With the intraoral devices, that was not possible. Another advantage is that previous electrostimulators were expensive, whereas TENS units are less expensive. TENS is a nonpharmacologic method. TENS can be used in patients with TMJ disorders and edentulous patients.

The effectiveness of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in healthy adult subjects in stimulating the parotid saliva flow rate.[6] They concluded their study that TENS was effective in increasing parotid gland SF in 2/3rd of healthy subjects. So, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate whether the TENS is effective in stimulating parotid SF in patients having complaint of dry mouth.

In the present study, we have used modified Carlson Crittenden cup for the collection of saliva from parotid glands bilaterally, which had been consistently used in previous studies that determined the parotid SF rates.[10] In the current study, the saliva is collected in preweighed test tubes and weighed after the collection of saliva to get the accurate value and the weight is then converted to volume mL/min as done in previous studies. Our saliva collection method was an improvement over previous electrostimulation studies, which were very subjective and prone to contamination by nasal and gastric secretions as well as food debris.

In the present study, most of the patients, i.e., 19 out of 25 showed significant increase in SF after transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. All the patients who participated in the study had residual saliva before stimulation; this may be the fact why most of patients showed increase in SF. One of the previous studies showed that TENS by itself is less likely to be effective in cases where there is no baseline saliva and in cases where there is residual salivary function TENS appears to be potential. TENS may act more efficiently as an accelerator of SF rather than an initiator.[6]

Six patients out of 25 patients did not have significant increase in SF rate. All these patients had a positive history of xerogenic drugs. This may be the reason why these patients did not have significant increase in parotid SF rate after the transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation.

It had been reported that electrically stimulating the nerve will elicit a reaction which may stimulate the salivary reflex.[9] This is the possible mechanism by which TENS stimulated the SF. TENS could have stimulated the auriculotemporal nerve which is the secretomotor nerve to the parotid gland. Electrical stimulation of the parasympathetic nerve will result in production of copious amount of watery saliva which will be useful in relieving the xerostomia.[6]

An unexpected finding in this study is that there were gender differences. In the present study, males produced significantly more saliva when compared to females after stimulation with TENS which was consistent previous study.[6]

Only one side effect observed during the study was the facial muscle twitching found in 5 patients. However, this symptom ceased immediately after the intensity was reduced. Subjective measures of the amount of saliva the subjects perceived to have been not recorded. Owing to the collection method, the mouth remained somewhat open during the study, which may have produced drying effects that would have influenced subjective measurements.

The subjects in the study could have been grouped according to the etiology of the dry mouth. This would have given relationship between the etiology and the efficiency of stimulation of TENS. Sialometry if done would have ensured the patients are having hyposalivation, but the questionnaire used in the study was also proved to be efficient in diagnosing the patients with dry mouth.

CONCLUSION

If the patients are having a complaint of dry mouth and there is presence of residual SF then TENS can accelerate the salivary production. TENS can be used in patients allergic to secretogogues.

Aspects for future study should include how long the increase in saliva flow lasts after turning off the TENS unit, the ability of TENS to stimulate parotid SF specifically when there is none at baseline, patient acceptance, subjective measures, and usefulness of TENS alone versus in combination with other sialogogues.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth G, Calmes R, editors. Oral Biology. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1981. Salivary glands and saliva; pp. 196–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Almeida Pdel V, Grégio AM, Machado MA, de Lima AA, Azevedo LR. Saliva composition and functions: A comprehensive review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guggenheimer J1, Moore PA. Xerostomia: Etiology, recognition and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:61–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawes C. How much saliva is enough for avoidance of xerostomia? Caries Res. 2004;38:236–40. doi: 10.1159/000077760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nederfors T. Xerostomia and hyposalivation. Adv Dent Res. 2000;14:48–56. doi: 10.1177/08959374000140010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hargitai IA, Sherman RG, Strother JM. The effects of electrostimulation on parotid saliva flow: A pilot study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:316–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox PC. Xerostomia: Recognition and management. Dent Assist. 2008;77:18. 20, 44-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenkels LC, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Biochemical composition of human saliva in relation to other mucosal fluids. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:161–75. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ten Cate AR. Oral Histology: Development, Structure and Function. 5th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shern RJ, Fox PC, Li SH. Influence of age on the secretory rates of the human minor salivary glands and whole saliva. Arch Oral Biol. 1993;38:755–61. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(93)90071-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]