Abstract

Background:

To evaluate the efficiency of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on the incidence of alveolar osteitis (AO) in patients with potential risk factors for the development of AO.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted in 150 patients visiting the outpatient department of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Patients with potential risk factors for the development of AO which included smokers, alcoholics, postmenopausal women, patients on oral contraceptives, pericoronitis, and bruxism were included for the study. Patients were randomly divided into two groups. Group A consisted of 75 patients in which PRP was placed in the socket after extraction. Group B consisted of 75 patients in which sockets were left for normal healing without the placement of PRP. The patients were assessed for pain and dry socket on the 3rd and 5th postoperative day.

Results:

All the local signs and symptoms of inflammation were mild to moderate and subsided in normal course of time. Pain was less in Group A where the extraction sockets were treated with PRP. Soft-tissue healing was also statistically significant on the PRP treated site when compared to the other group where PRP was not placed into the socket after extraction. The incidence of AO among the patients who have the potential risk factor for the development of the same was significantly reduced in Group A.

Conclusion:

The study showed that autologous PRP is a biocompatible material and has significantly improved the process of soft-tissue healing, reduced pain, and decreased the incidence of AO in the extraction socket when treated with PRP.

Keywords: Alveolar osteitis, bone morphogenetic protein, case–control study, extraction, plasma-rich growth factors, platelet-rich plasma

INTRODUCTION

Alveolar osteitis (AO) is a well-known local complication of the extraction or surgical removal of teeth. AO is defined as postoperative pain inside and around the extraction site, which increases in severity at any time between the 1st and 3rd day after the extraction, accompanied by a partial or total disintegrated blood clot within the alveolar socket with or without halitosis. In dry socket, the alveolar osseous walls are exposed, with total or partial clot loss, dark coloration, and a fetid odor. Continuous, intense, and frequently radiating pain is present that is not relieved by analgesics. Local hyperthermia and lymphadenopathy can also occur with this type of alveolitis. It is suggested that AO is the result of either bacterial infection or by the release of tissue factors leading to the activation of plasminogen and the subsequent fibrinolysis of the blood clot.[1]

The increase in recovery period translates into increased cost to the surgeon and patients who develop AO typically require multiple postoperative visits to manage this condition.[2] Many suggested methods exist for the prevention of AO including topical and systemic steroids, topical and systemic antibiotics, matrix forming resorbable materials, antifibrinolytic agents, and various combinations of the above. No single method has gained universal success or acceptance although a large number of practitioners continue to use “their method” often without controlled studies to support its use.[3]

It is now well known that platelets have many functions beyond that of hemostasis. Platelets contain important growth factors that, when secreted, are responsible for increasing cell mitosis, increasing collagen production, recruiting other cells to the site of injury, initiating vascular ingrowth, and inducing cell differentiation. These are all crucial steps in early wound healing. Using the concept that if a few are good, then a lot may be better, increasing the concentration of platelets at a wound may promote more rapid healing. It seems very logical that increasing the concentration of platelets in a bone graft and therefore increasing the concentration of growth factors may lead to a more rapid and denser regenerate.[4]

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an autologous concentration of human platelets in a small volume of plasma. Because it is a concentration of platelets, it is also a concentration of the seven fundamental protein growth factors proved to be actively secreted by platelets to initiate all wound healing. These growth factors include three isomers of platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFaa, PDGFpp, and PDGFap), two of the numerous transforming growth factors-p (TGFp1 and TGFp2), vascular endothelial growth factor, and epithelial growth factor. All these growth factors have been documented to exist in platelets. As these concentrated platelets are suspended in a small volume of plasma, PRP is more than just a platelets concentrate; it also contains the three proteins in blood known to act as cell adhesion molecules for osteoconduction and as a matrix for bone, connective tissue, and epithelial migration. These cell adhesion molecules are fibrin itself, fibronectin, and vitronectin.[5] The purpose of this study is to determine the efficiency of PRP on the incidence of AO in patients with potential risk factors for the development of AO; this study also aimed to examine the incidence of AO formation and its association with immediate placement of PRP gel in the extraction alveolus socket.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

These study participants involved a total of 150 patients, both female and male patients, who were referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery for the removal of the 1st, 2nd or 3rd mandibular molar. After obtaining the complete history, patients were examined clinically and were explained about the procedure, its complication, and the follow-up period involved in the study. The patients who were willing were enrolled for the study. Informed consent was taken and ethical clearance was obtained; patients of age between 30 and 60 years and with potential risk factors for the development of AO which included smokers, alcoholics (ALC), postmenopausal women (PML), patients on oral contraceptives (OC); pericoronitis (PC), and bruxism (BM) were selected for the study. All mandibular molar teeth irrespective of its position and eruptive status (erupted, partially erupted, and complete bone impaction) were included in the study. Patients below 30 years and above 60 years, pregnant and lactating mothers, patients having bleeding disorders, on antiplatelet drugs, undergoing chemotherapy, and patients with acute phase of PC were excluded from the study.

Study participants were randomly divided into two groups. Group A consisted of 75 patients, in whom PRP was placed in the socket after extraction. Group B consisted of 75 patients in them the sockets were left for normal healing without the placement of PRP. The patients were assessed for pain and dry socket on the 3rd and the 5th postoperative day.

Protocol for obtaining platelet-rich plasma in an autologous fibrin clot

Under all aseptic techniques, 8 ml of blood was drawn intravenously from the antecubital region of the patient's forearm using Vacutainer needle and BD Vacutainers (each 4.5 ml) containing citrate-phosphate-dextrose with adenine (0.5 ml each). The Vacutainers were thoroughly shaken to ensure mixture of anticoagulant with the drawn blood. The whole blood is then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min; the supernatant formed is platelet-poor plasma and buffy coat. Platelet-poor plasma and buffy coat and upper 1 mm red blood cell layer are collected in a fresh Vacutainer and again centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The upper half of the supernatant is discarded and the lower half is mixed thoroughly to yield PRP. The lower half is then mixed with 0.5–1 cc of CaCl2 and kept undisturbed for 2–3 min to yield PRP gel. The freshly prepared PRP was placed into the selected extraction socket.

AO was assessed on the following criteria:

Throbbing pain refractory to routine analgesics

Absence of granulation tissue

Absence of blood clot in the extraction socket

Presence of fetid odor and taste

Presence of lymphadenopathy.

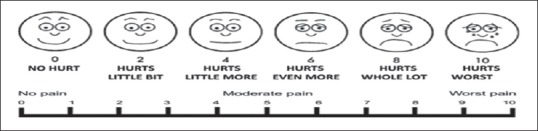

Pain was evaluated using the visual analog Wong-Baker pain rating scale,[6] and evaluation of tissue healing was done using healing index of Landry et al.[7]

RESULTS

The present study involved 75 patients in Group A which involved 42 males and 33 females with a mean age of 43.96 years where PRP was placed into the extraction socket and 75 patients in Group B which consisted of 40 males and 35 females with a mean age of 44.75 years where the extraction socket was left for healing without placing any PRP.

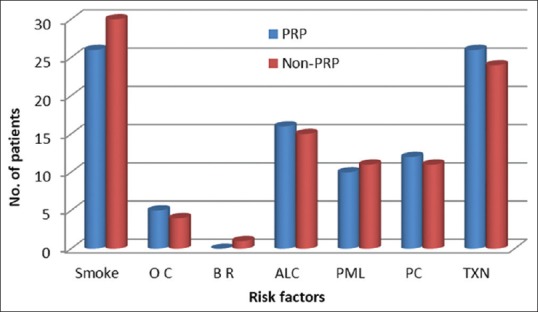

Figure 1 represents the number of patients in each high risk category in both group A and B. Group A included 26 smokers, 5 patients on oral contraceptives, 16 alcoholics, 10 post-menopausal women, 12 cases with pericoronitis, 26 traumatic extractions. Group B included 30 smokers, 4 patients on oral contraceptives, 1 with bruxism, 15 alcoholics, 11 post-menopausal women, 11 cases with pericoronitis, 24 traumatic extractions.

Figure 1.

Number of patients in each high risk category

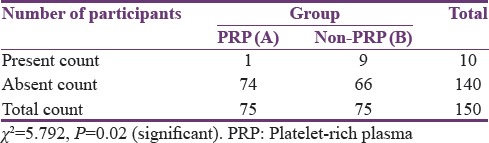

Out of 75 patients in Group B, 9 patients (12%) had AO and in Group A, the number of patients with AO was reduced to 1 patient (1.3%). The results were statistically analyzed using Chi-square test. Statistically significant difference was obtained in the number of patients having AO between Group A and Group B [Table 1].

Table 1.

Incidence of alveolar osteitis in Group A and Group B

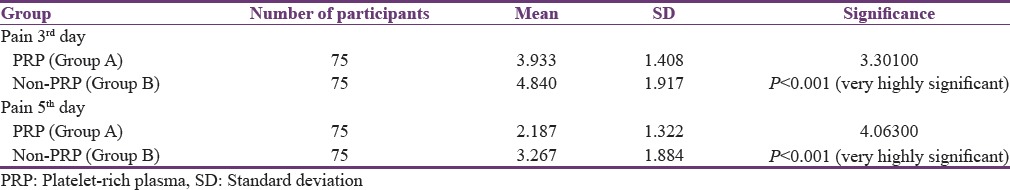

Visual analog scale was used to assess pain on the 3rd and 5th postoperative day. The mean pain score on day 3 for Group A was 3.933 and for Group B was 4.840, and the mean pain score on the 5th postoperative day for Group A was 2.187 and for Group B was 3.267. The results were analyzed using paired t-test. The difference between the mean pain scores on the 3rd postoperative day and 5th postoperative day between Group A and Group B was statistically significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean value of pain between Group A and Group B

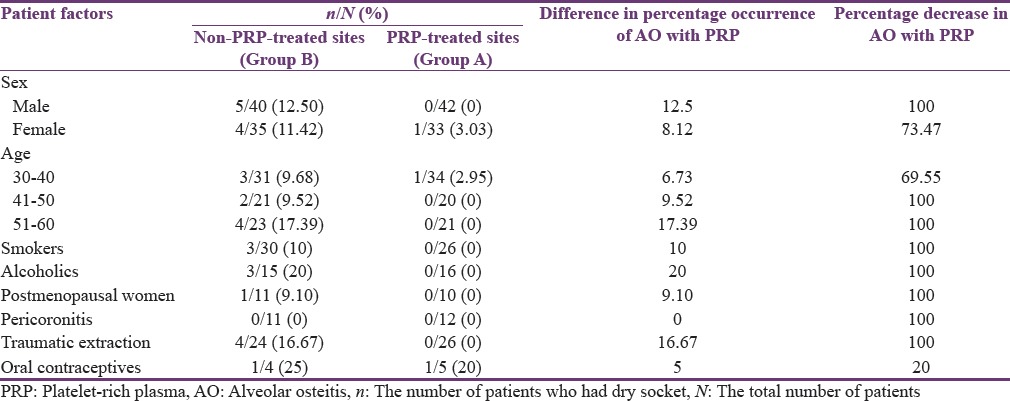

Out of the 40 males in Group B and 42 males in Group A, 5 (12.5%) patients of Group B had dry socket and 100% reduction of AO was obtained in Group A. Among female patients, 11.42% (4 out of 35) had AO in Group B and 3.03% (1 out of 33) in group A, respectively. In Group B, highest percentage of AO, i.e., 17.39% was seen in patients between 50 and 60 years of age, followed by 9.68% in patients between 30 and 40 years of age and least in patients between 40 and 50 years of age at 9.52%. In group A where PRP was used, 100% reduction in AO was achieved in patients aged between 50 and 60 years and 40 and 50 years, and the incidence of AO was reduced by 69.55% in patients aged between 30 and 40 years [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of nonplatelet-rich plasma treated (Group B) and platelet-rich plasma treated (Group A) for individual patient factors

Figure 2 represents the number of patients in each high-risk category in both Group A and B. Group A included 26 smokers, 5 patients on OC, 16 ALC, 10 PML, 12 cases with PC, and 26 traumatic extractions (TXN). Group B included 30 smokers, 4 patients on OC, 1 with BM, 15 ALC, 11 PML, 11 cases with PC, and 24 TXN.

Figure 2.

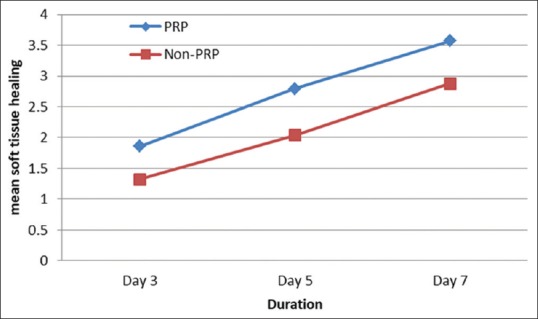

Comparison of mean values among groups for soft tissue healing. *P<0.001

Figure 3 represents a comparison of the mean values of the soft-tissue healing on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th postoperative day between the two groups; statistical analysis was carried out using paired t-test, and statistical significance was observed between the groups (P < 0.001). The mean value for Group A was 1.86 on the 3rd postoperative day, 2.79 on the 5th, and 3.57 on the 7th postoperative day. The mean value for Group B was 1.32 on the 3rd, 2.04 on the 5th, and 2.88 on the 7th postoperative day.

Figure 3.

Wong-Baker pain rating visual analog scale[6]

DISCUSSION

AO is a local complication of extraction or after surgical removal of teeth. It is defined as postoperative pain inside and around the extraction site, which increases in severity at any time between the 1st and 3rd day after the extraction, accompanied by a partial or total disintegrated blood clot within the alveolar socket with or without halitosis.[3]

The cause of AO is poorly understood. It is suggested that AO is the result of either bacterial infection or by the release of tissue factors leading to the activation of plasminogen and the subsequent fibrinolysis of the blood clot.[3]

Normally, blood clot initiates the healing and regeneration of hard and soft tissue postoperatively. PRP is a way to enhance the body's natural wound healing mechanisms. A natural blood clot contains mainly red blood cells, approximately 5% platelets and <1% white blood cells. Using PRP involves taking a sample of a patient's blood postoperatively, concentrating autologous platelets, and applying the resultant gel to the surgical site. This technique produces a blood clot that has nearly a reverse ratio of red blood cells and platelets compared to with a natural blood clot. Platelets are primarily involved in wound healing through clot formation and the release of growth factors that initiate and support wound healing.[8] Surgical sites enhanced with PRP have been shown to heal at 2–3 times that of normal surgical sites. Thus, PRP can be great adjunct to many surgical procedures.[9,10,11]

In our study, PRP was prepared from 8 cc of patient's blood and centrifuging the blood twice in a clinical centrifuge as advocated by many authors.[12,13,14]

According to Okuda et al., the concentration of platelets in PRP gel was measured by a platelet cell counter and was consistently found to be 3.5–4 times greater than the whole blood platelet count. This assures a therapeutic concentration of growth factors.[15]

Plasma-rich protein is activated to form PRP gel, thus causing degranulation of α-granules present in the platelets and releasing the growth factors. The various agents for the activation reported in literature include CaCl2 alone, CaCl2 plus bovine thrombin, human thrombin, autologous bone, and whole blood which contains thrombin.[16] Landesburg in 1998 had demonstrated antibodies to clotting factors V, XI and thrombin when bovine thrombin was used to activate. This resulted in risk of life-threatening coagulopathies. Hence, bovine thrombin was not used to activate PRP gel in the present study.[9] In our study, CaCl2 alone was mixed with PRP to form an autologous platelet gel. This platelet gel was free of eliciting any antigen–antibody as it was prepared from patient's own blood.

In a study by Marx, the use of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid as anticoagulant is not recommended because it fragments platelets. Citrate phosphate dextrose (CPD) is preferred and is the anticoagulant used by the blood bank for platelet transfusion because it can preserve the integrity of the platelet membrane.[9,17,18] The importance of this relates to the fact that growth factors are extruded from platelets during exocytosis. During this process, completion of protein molecule and formation of the tertiary structure occur. Fragmented platelets may spill more growth factors into the solution, providing for higher levels, but their tertiary structure is altered, and therefore, their activity and effectiveness are reduced.[17] In our study, CPD was used to preserve the platelet membrane integrity.

The beneficial effects of PRP for decreasing the incidence of AO may be related to a number of signaling proteins found in the platelets, including multiple growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, nerve growth factor, TGF-β1 and TGF-β2, platelet-derived growth factors, and cytokines such as angiopoietin-2 and interleukin-1. These factors stimulate cell mitosis and differentiation, increase collagen production, recruit leukocytes and other cells to the surgical site, and initiate vascular ingrowth. Growth factors promote both soft and hard tissue healing and angiogenesis. In addition, platelets promote clot formation, which is beneficial in healing. Aside from platelets, PRP also contains white blood cells that can inhibit bacterial growth. Therefore, PRP application mitigates the currently accepted causes of AO by facilitation of clot and soft-tissue formation and inhibition of bacterial colonization.[8]

In this study, the inclusion criteria were patients who are aged between 30 and 60 years with potential risk factors for the development of AO which included smokers, ALC, PC, postmenopausal ladies, TXN, BM, and OC. Factors that have been shown to negatively influence the outcome of the study were eliminated while formulating the exclusion criteria of patients since they may alter the treatment plan and influence the result in an aberrant manner.

In the present study, we also found that PRP when activated formed a gelatinous mass. Whitman et al. concluded that the adhesive nature of the gel also enables predictable flap adhesion and hemostasis. As the gel consolidates, a more definite seal is obtained than with primary closure alone.[18]

In the present study, pain was measured using visual analog scale[6] on the 3rd and 5th postoperative day. Mean value for pain was more in Group B on both the 3rd and 5th postoperative day. Postoperative pain was less in the Group A, and statistically significant difference was observed in the mean score for pain between Group A and Group B on the 3rd and 5th postoperative day. Soft-tissue healing was evaluated postoperatively on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th day. Mean soft-tissue healing on the 3rd day for Group A is 1.87 and for Group B is 1.32, 5th day for Group A is 2.79 and for Group B is 2.04, and 7th day for Group A is 3.57 and for Group B is 2.88. This statistically significant result indicates a better soft-tissue healing of extraction sockets treated with PRP as compared to the non-PRP sockets. Our finding is supported by the similar study where the authors reported that soft-tissue healing was significantly better in the cases where extraction sockets were treated with PRP. Similarly, positive effect was demonstrated by PRP to enhance soft-tissue healing in postrhytidectomy wounds as was evidenced by less edema and ecchymosis.[19,20]

In Group B, AO formation was seen highest in the 3rd molar extraction site (17.64%) followed by the first molar extraction site (7.69%) and least in the second molar extraction site (6.66%). The percentage of AO formation in Group A was reduced to 2.43% in the third molar extraction site, and 100% reduction of AO was achieved in the first and second molar extraction sites. In a review of literature published on 2010, it is shown that AO is more common following the extraction of mandibular third molars. It is believed that increased bone density, decreased vascularity, and a reduced capacity of producing granulation tissue are responsible for the site specificity. The area specificity is probably due to the large percentage of surgically extracted mandibular molars and may reflect the effect of surgical trauma rather than the anatomical site.[4]

In the present study, OC was one of the potential risk factors that were associated with highest number (25%) of AO, followed by ALC (20%), TXN (16.67%), smokers (10%), and PML (9.10%). In Group A, the chance for AO for patients on OC was reduced by 20%, and for others, it was reduced by 100%.

OC is the only medication associated with developing AO. OC became popular in the 1960s, and studies conducted after 1970s show a significantly higher incidence of AO in females. Sweet and Butler found that this increase in the use of OC positively correlates with the incidence of AO. Estrogen has been proposed to play a significant role in the fibrinolytic process. It is believed to indirectly activate the fibrinolytic system (increasing factors II, VII, VIII, X, and plasminogen) and therefore increase lysis of the blood clot. Freymiller EG, Aghaloo TL further concluded that the probability of developing AO increases with increased estrogen dose in the OC.[4]

In this study, 12.5% of males were prone to AO when compared to 11.42% of females. In a review of literature published by Kolokythas et al. in 2010, it is given that female gender regardless of OC use is a predisposition for the development of AO, MacGregor reported a 50% greater incidence of AO in women than that in men in a series of 4000 extractions, while Colby reported no difference in the incidence of AO associated with gender.[4]

According to findings from this study, those patients aged between 50 and 60 years and those females on OC are at high risk for the formation of AO, followed by TXN, ALC, smokers, and PML. Our result with regard to less pain and enhanced soft-tissue healing may be attributed to the above-mentioned advantages that PRP possesses.

The limitation of the present study was that the sample size was small consisting of just 150 patients and a short follow-up duration of 7 days. Many literatures have been reported in, where long-term follow-up of 2–5 years has been done. Densitometric analysis evaluating postoperative bone formation was not done in the study as comparison between two independent individuals is not possible.

CONCLUSION

In this study, autologous PRP was used as adjunct to enhance soft-tissue healing and to reduce the incidence of AO in a group of patients who have the potential risk factors for the development of AO. The study clearly indicates a definite improvement in the soft-tissue healing and significantly reduced the number of AO in patients, with potential risk factors for the development AO as compared to the other group in which extraction sockets were not treated with PRP. This improvement in the wound healing, decrease in pain, and reduction in the number of dry sockets signifies and highlights the use of PRP, certainly as a valid method in inducing and accelerating wound healing and as a method to prevent the formation of AO in patients who are more prone to for the development of AO. Moreover, the preparation of PRP by collecting the blood in the immediate preoperative period avoids a time-consuming visit to the blood bank for the patient. An added benefit for PRP noted in the present study is its ability to form a biological gel that provided clot stability and function as an adhesive. The procedure for PRP preparation is simple, cost-effective, and has demonstrated good results.

The present study was done with a follow-up of just 7 days; further clinical trials with longer duration follow-up with a larger sample size should be done to get more affirmative and conclusive results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cardoso CL, Rodrigues MT, Ferreira O, Júnior, Garlet GP, de Carvalho PS. Clinical concepts of dry socket. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1922–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolokythas A, Olech E, Miloro M. Alveolar osteitis: A comprehensive review of concepts and controversies. Int J Dent. 2010;2010:249073. doi: 10.1155/2010/249073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fridrich KL, Olson RA. Alveolar osteitis following surgical removal of mandibular third molars. Anesth Prog. 1990;37:32–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freymiller EG, Aghaloo TL. Platelet-rich plasma: Ready or not? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: Evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCafeery M, Parson C. Pain: Clinical Manual. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Mosby; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landry RG, Turnbull RS, Howley T. Effectiveness of benzydamyne HCl in the treatment of periodontal post-surgical patients. Res Clin Forum. 1988;10:105–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi BH, Im CJ, Huh JY, Suh JJ, Lee SH. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on bone regeneration in autogenous bone graft. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:56–9. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landesberg R, Moses M, Karpatkin M. Risks of using platelet rich plasma gel. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:1116–7. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson NE, Roach RB., Jr Platelet-rich plasma: Clinical applications in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1383–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okuda K, Kawase T, Momose M, Murata M, Saito Y, Suzuki H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma contains high levels of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta and modulates the proliferation of periodontally related cells in vitro. J Periodontol. 2003;74:849–57. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robiony M, Polini F, Politi M. Osteogenesis distraction and platelet rich plasma for bone reconstruction of the severely atrophic mandible: Preliminary results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:630–5. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tözüm TF, Keçeli HG, Serper A, Tuncel B. Intentional replantation for a periodontally involved hopeless incisor by using autologous platelet-rich plasma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsay RC, Vo J, Burke A, Eisig SB, Lu HH, Landesberg R. Differential growth factor retention by platelet-rich plasma composites. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuda K, Kawase T, Momose M, Murata M, Saito Y, Suzuki H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma contains high levels of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta and modulates the proliferation of periodontally related cells in vitro. J Periodontol. 2003;74:849–57. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonshor A. Technique for producing platelet-rich plasma and platelet concentrate: Background and process. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:547–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marx RE. Quantification of groeth factor Levels using a simplified method of platelet-rich plasma gel preparation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:300–1. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitman DH, Berry RL, Green DM. Platelet gel: An autologous alternative to fibrin glue with applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1294–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vivek GK, Sripathi Rao BH. Potential for osseous regeneration of platelet rich plasma: A comparitive study in mandibular third molar sockets. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2009;8:308–11. doi: 10.1007/s12663-009-0075-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell DM, Chang E, Farrior EH. Recovery from deep-plane rhytidectomy following unilateral wound treatment with autologous platelet gel: A pilot study. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:245–50. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.3.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]