Abstract

Introduction:

The increasing problem of antibiotic drug resistance by pathogenic microorganisms in the past few decades has recently led to the continuous exploration of natural plant products for new antibiotic agents. Many consumable food materials have good as well as their bad effects, good effect includes their antibacterial effects on different microorganisms present in the oral cavity. Recently, natural products have been evaluated as source of antimicrobial agent with efficacies against a variety of microorganisms.

Methodology:

The present study describes the antibacterial activity of three selected fruit juices (Apple, Pomegranate and Grape) on endodontic bacterial strains. Antimicrobial activity of fruit juices were tested by wel l diffusion assay by an inhibition zone surrounding the well. The aim of the study was to evaluate the antibacterial activity of three fruit juises on different endodontic strains.

Result:

Agar well diffusion method was adopted for determining antibacterial potency. Antibacterial activity present on the plates was indicated by an inhibition zone surrounding the well containing the fruit juice. The zone of inhibition was measured by measuring scale in millimeter. Comparision between antibacterial efficacy of all three fruit juices against Enterococcus feacalis and Streptococcus mutans was observed with significant value of P ≤ 0.05.

Conclusion:

The results obtained in this study clearly demonstrated a significant antimicrobial effect of apple fruit juice against Enterococcus fecalis and Streptococcus mutans. However, preclinical and clinical trials are needed to evaluate biocompatibility & safety before apple can conclusively be recommended in endodontic therapy, but in vitro observation of apple effectiveness appears promising.

Keywords: Agar well diffusion method, antibacterial activity, Citrus paradisi, Malus domestica, Punica granatum

INTRODUCTION

Infection of the root canal system occurs as a result of multiple activities of microorganisms, which can be Gram-positive or Gram-negative, facultative aerobic or anaerobic bacteria, fungi, or viruses. The Enterococcus faecalis is the most common microorganism involved in endodontic pathologies, especially with regard to secondary infections and to the appearance of periapical lesions.[1] On the other hand, Streptococcus mutans is Gram-positive facultative anaerobic bacteria which is commonly found in the human oral cavity and is a major contributor of dental caries.

The increasing problem of antibiotic drug resistance by pathogenic microorganisms in the past few decades has recently led to the continuous exploration of natural plant products for new antibiotic agents.[2]

The use of natural products in dentistry has been justified by their popular use, low cost and appropriate antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities.[1]

Fruits are one of the oldest forms of food known to man. There are many references to fruits in ancient literature. The people in ancient times regarded fruits to be endowed with magic or divine properties.[3] There is a great demand of fruit juices in the treatment of various illnesses such as arthritis, heart diseases, muscle aches, and drug addiction.[4]

Apple (Malus domestica) is a worldwide diffused fruit with many health benefits, mostly due to the presence of phenolic compounds. Apples also ranked second for total content of phenolic compounds, including quercetin, catechin, phloridzin, and chlorogenic acid, all of which are strong antioxidants and thus capable of counterbalancing free radical activities that may cause cell injuries. The phytochemical composition varies greatly with the different varieties of apples and thereby helps in developing new antimicrobials against various infectious diseases.[3]

Pomegranate (Punica granatum) fruits are widely consumed, fresh and in commercial products, such as juices, jams, and wines. Most pomegranate fruit parts are known to possess enormous antioxidant activity. Pomegranate belongs to punicaceae family. The edible part of fruit contains considerable saccharides, polyphenol, and important minerals. The major class of pomegranate phytochemicals is the polyphenols (phenolic rings bearing multiple hydroxyl groups) that predominate in the fruit. Pomegranate polyphenols include flavonoids (flavonols, flavanols, and anthocyanins), condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins), and hydrolysable tannins (ellagitannins and gallotannins).[3]

Grape (Citrus paradisi) belongs to the Citrus genus, a taxa of flowering plants in the family Rutaceae. Grape is one of the citrus fruits cultivated and consumed in Nigeria.[4] It acts as a fabulous source of vitamin C and a wide variety of essential nutrients required by the body. Fresh fruits and their hand-squeezed or industrially processed juices contain mostly flavanones and flavones.[3]

The aim of this study is to:

Evaluate the antibacterial activity of three selected fruit juices on clinical endodontic bacterial strains

Find out the effective fruit juice with highest antimicrobial activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of fruits

Fresh fruits were purchased and collected from market. Different fruits used in the study were Pomegranate (P. granatum), Apple (Musca domestica), and grapes (C. paradisi).[3]

Preparation of juices

All fruits were brought to laboratory, washed in running tap water; surface sterilized with 70% alcohol and then rinsed with sterile distilled water. Fresh juices of these three selected fruits were prepared in the laboratory just before the experiments.[5]

Test organisms

Two microorganism Enterococcus fecalis and S. mutans were obtain from the Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh. Strains were confirmed by culture on blood agar, macCkonky agar, and nutrient agar plate, Gram-staining, catalase and oxidase test, and biochemical characteristics. Strains were maintained in slants at 4°C for further use.

Preparation of bacterial inoculums

For testing antimicrobial activity, E. fecalis and S. mutans bacterial strains were adjusted equal to 0.5 McFarland standards by adding sterile distilled water. McFarland standards are used as a reference to adjust the turbidity of microbial suspension so that number of microorganisms will be within a given range.

Assessment of antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity of three fruit juices was tested by well-diffusion assay. Inoculums of each of bacterial strains were suspended in 5 ml of Brain Heart infusion broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, 100 μl of inoculums was spread on sterile Muller-Hinton agar plates. Wells of 8 mm size were made with sterile borer into Muller-Hinton agar plates containing the bacterial inoculums and the lower portion was sealed with a little molten agar medium. 100 μl volume of the fruit extract was poured into each well of inoculated plates. The plates thus prepared were left at room temperature for 10 min allowing the diffusion of the extracts into the agar. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the plates were observed. Antibacterial activity present on the plates was indicated by an inhibition zone surrounding the well containing the fruit juice. The zone of inhibition was measured by measuring scale in millimeter.

Data collected was coded, computerized, and analyzed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 9.0) (IBM, USA).

RESULTS

In the present work, antibacterial effect of selected fruit juices was studied on Enterococcus faecalis and S. mutans. Antibacterial activity of three fruit juices-pomegranate (P. granatum), Apple (M. domestica), Grape (C. paradisi) was studied. Agar well-diffusion method was adopted for determining antibacterial potency. Antibacterial activity present on the plates was indicated by an inhibition zone surrounding the well containing the fruit juice. The zone of inhibition was measured by measuring scale in millimeter.

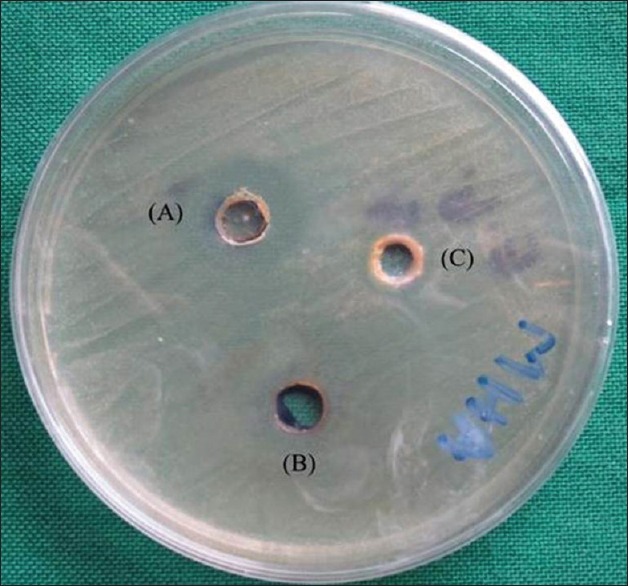

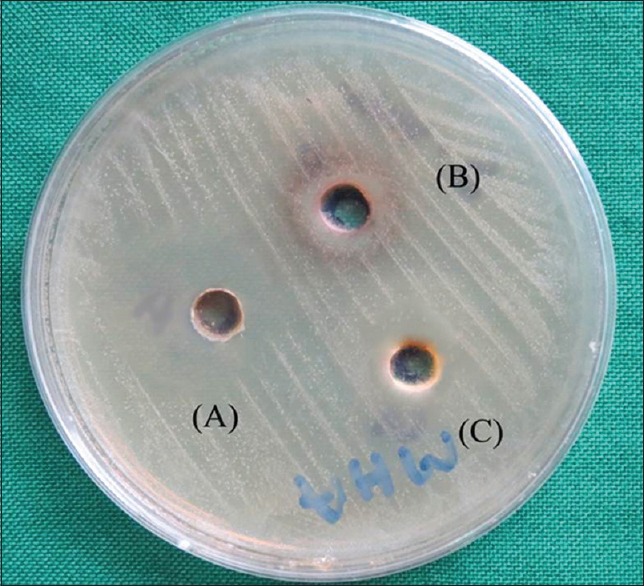

Results obtained for antibacterial studies reveal following findings. Juice of apple exhibited antibacterial activity toward E. faecalis and S. mutans, with more activity observed with S. mutans. There was significant variation in the antibacterial activities of different fruit juices. Against E. faecalis, [Figure 1] the apple juice exhibited highest antibacterial activity among all three fruits used with diameter of inhibition zone (DIZ) values between 8.9 mm and 9.9 mm with mean value of 9.4 mm [Table 1]. The inhibitory effect recorded for S. mutans, [Figure 2] by apple juice was between 11.4 mm and 12.5 mm with mean value of 12 mm [Table 1]. Among all, the three fruits used low antibacterial activity was recorded with fruits pomegranate and grape. The results for pomegranate and grape juices have shown some variation with small diameter of zone of inhibition having mean value of 0.7 mm and 0.4 mm, respectively, against both E. faecalis and S. mutans.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial activity of (A) apple juice, (B) pomogranate juice, (C) Grape juice against Enterococcus faecalis. Maximum diameter of inhibition zone shown by apple juice

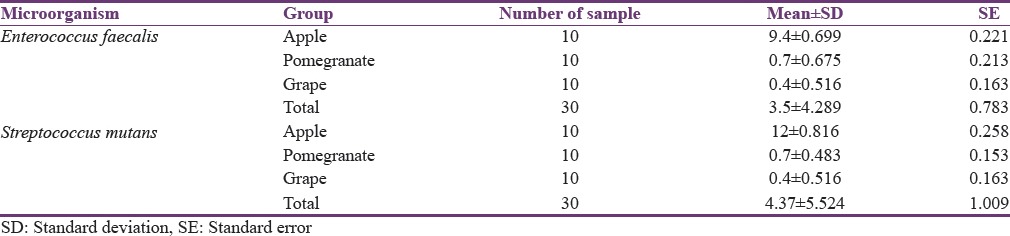

Table 1.

Mean diameter of zone of inhibition of different fruit juices

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial activity of (A) apple juice, (B) pomogranate juice, (C) grape juice against Streptococcus mutans. Maximum diameter of inhibition zone shown by apple juice

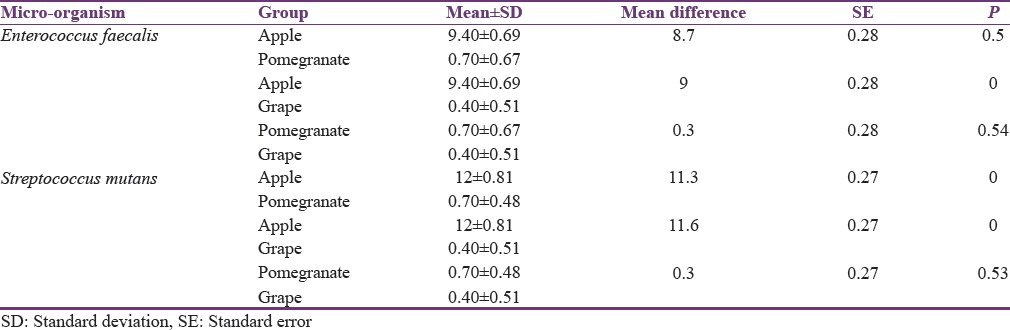

Comparision between antibacterial efficacy DIZ of all three fruit juices against E. faecalis and S. mutans was observed with significant value of P ≤ 0.05 [Table 2]. On comparision, juices of apple and pomegranate showed significant value of P ≤ 0.05 against both E. faecalis and S. mutans. Comparision of juices of apple and grapes also showed significant value of P ≤ 0.05 against both E. faecalis and S. mutans. However, when antibacterial efficacy DIZ of pomegranate and grapes was compared showed significant value of P > 0.05, which makes it insignificant.

Table 2.

Comparison between different fruit juices to evaluate their efficacy

Based on the above-mentioned data [Tables 1 and 2], the result shows that apple showed the maximum antibacterial efficacy DIZ among all three fruit juices against E. faecalis and S. mutans with significant value of P ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of drug resistance with patient's poor compliance, drugs adverse effects and the higher cost of therapy combinations, indicates a strong need for therapy regimens with similar or higher antibiotics beneficial properties but with lesser adverse effects.[3]

A considerable interest has been developed over the years in fruits and vegetables due to their potential biological and health promoting effects. The protective effect of fruits and vegetables has been attributed to their bioactive antioxidant constituents, including vitamins, carotenoids, and polyphenols.[6] Among various antioxidants present in fruits and vegetables, polyphenol oxidase (including anthocyanins) have received much attention since being reported to have a positive influence on human health. The consumption of polyphenol rich juice enhances antioxidant status, reduces oxidative DNA damages, and stimulates immune cell functions.[7] The protection provided by their antioxidant can be explained by the capacity of active compounds to scavenge free radicals, which is responsible for the oxidative damage of lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids.[8]

Antibacterial activity of fresh juice of three fruits as follows: pomegranate (P. granatum), apple (M. domestica), and grapes (Vitis vinifera) was tested on E. faecalis and S. mutans. The antibacterial potency was initially determined by the agar well-diffusion method. Among all the fruits, highest antibacterial activity was recorded with apple fruit juice. Antimicrobial activity of tropical fruits – apple, pomegranate, guava, and orange was studied by Anshika Malaviya and Neeraj Mishra.[9] In their study, aqueous and ethanolic extracts were used against four bacterial cultures – Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and P. aeruginosa with DIZ values range between 2 and 10 mm, interestingly the results report that aqueous extract of apple exhibited high antibacterial effect than ethanolic extracts. These results are in accordance with the study conducted by us.

In another study by Florida Fratianni et al.,[10] antimicrobial effect of two varieties of apples: organically produced and conventionally produced apples were tested against useful lactobacillus species and pathogenic microorganisms, i.e., Bacillus cereus, which is responsible for several cases of foodborne illness and the enterohemorrhagic E. coli, that causes serious cases of food poisoning. None of the apple extracts assayed gave positive results against the 6 strains of lactic acid bacteria. The conventional extracts determined the formation of inhibition zones, having a diameter of about 10 mm, only against the three strains of B. cereus. The extracts from the organically grown apple exhibited a clear antimicrobial activity, both against the strains of B. cereus and against the two strains of E. coli. The effectiveness found against the pathogenic microorganism E. coli in their study can be considered of promising importance as this strain produces verocytotoxins and causes hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. Effect of water and alcohol extracts of M. domestica (apple) was found to be effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria-B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa by Sun J. et al.[11] As is confirmed by our study.

In dentistry, the use of pomegranate (P. granatum) has been more frequently reported in the control of forming biofilm microorganisms.[12]

Vasconcelos et al. evaluated the antimicrobial activity of pomegranate extracts and determined the minimum inhibitory concentration at the concentrations of 5% and 10% against strains of Candida albicans, S. mutans, and Streptococcus mitis.[13]

Study by Sharma et al. reported the antibacterial efficacy of the aqueous, ethanolic, and acetic extracts of pomegranate (P. granatum), in the concentration of 5% against resistant clinical strains of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and E. faecalis. Accordingly, the pomegranate tincture used at a concentration of 5% is indicated in the control of root canal microorganisms.[14] This is contrary to our results.

Grape seeds are rich in monomeric phenolic compounds, such as catechins and epicatechins and have been reported to have numerous antiviral and antimutagenic properties by various investigators. Jayaprakasha et al. reported that all the grape seed extracts were antibacterial against Bacillus spp., S. aureus, E. coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[15]

Rhodes et al. investigated the antilisterial activity of grape juice and grape extracts derived from V. vinifera variety Ribier and also documented that grape juice was inactive against B. cereus, Salmonella Menston, E. coli, and S. aureus.[16]

Dabbah et al. showed that the oil of grape peels and other citrus fruits peel as well as their derivatives inhibited Escherichia coli, Salmonella sp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas spices.[17] These results are not coinciding with the study conducted by us.

CONCLUSION

The results obtained in this study clearly demonstrated a significant antimicrobial effect of apple fruit juice against E. faecalis and S. mutans. Microbial inhibition potential of apple fruit juice observed in this study opens perspectives for its use in endodontic therapies. However, preclinical and clinical trials are needed to evaluate biocompatibility and safety before apple can conclusively be recommended in endodontic therapy, but in vitro observation of apple effectiveness appears promising.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cavalcanti YW, Almeida LFD, Costa MMTM, Padilha WWN. Antimicrobial activity and ph evaluation of calcium hydroxide associated with natural products. Braz Dent Sci. 2010;13:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okunowo WO, Oyedeji O, Afolabi LO, Matanm E. Eessential oil of grape fruit (citrus paradisi) peels and its antimicrobial activities. Am J Plant Sci. 2013;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unnisa N, Tabassum H, Ali MN, Ponia K. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of five selected fruits of bacterial wound isolates. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2012;3:531–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tedesco I, Luigi Russo G, Nazzaro F, Russo M, Palumbo R. Antioxidant effect of red wine anthocyanins in normal and catalase-inactive human erythrocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2001;12:505–11. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(01)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sushma, Khan MA, Kumar M. Effect of storage on some biochemical parameters of selected fresh fruits juice. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2013;4:659–63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi H, Noguchi N, Niki E. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2001. Introducing natural antioxidant; pp. 147–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bub A, Watzl B, Blockhaus M, Briviba K, Liegibel U, Müller H, et al. Fruit juice consumption modulates antioxidative status, immune status and DNA damage. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:90–8. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aruoma OI. Free radicals, oxidative stress and antioxidants in human health and disease. J Am Oil Chem Sci. 1998;75:199–212. doi: 10.1007/s11746-998-0032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaviya A, Mishra N. Antimicrobial activity of tropical fruits. Biol Forum Int J. 2011;3:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fratianni F, Sada A, Cipriano L, Masucci A, Nazzaro F. Biochemical characteristics, antimicrobial and mutagenic activity in organically and conventionally produced Malus domestica, Annurca. Open Food Sci J. 2007;1:10–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun J, Chu YF, Wu X, Liu RH. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of common fruits. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7449–54. doi: 10.1021/jf0207530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salgado AD, Maia JL, Pereira SL, de Lemos TL, Mota OM. Antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of a gel containing Punica granatum linn extract: A double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14:162–6. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572006000300003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasconcelos LC, Sampaio FC, Sampaio MC, Pereira Mdo S, Higino JS, Peixoto MH, et al. Minimum inhibitory concentration of adherence of Punica granatum linn (pomegranate) gel against S. Mutans, S. Mitis and C. Albicans. Braz Dent J. 2006;17:223–7. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402006000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma A, Chandraker S, Patel VK, Ramteke P. Antibacterial activity of medicinal plants against pathogens causing complicated urinary tract infections. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2009;71:136–9. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.54279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaprakasha GK, Selvi T, Sakariah KK. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of grape (Vitis vinifera) seed extracts. Food Res Int. 2003;36:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes PL, Mitchell JW, Wilson MW, Melton LD. Antilisterial activity of grape juice and grape extracts derived from Vitis vinifera variety Ribier. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;107:281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabbah R, Edwards VM, Moats WA. Antimicrobial action of some citrus fruit oils on selected food-borne bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1970;19:27–31. doi: 10.1128/am.19.1.27-31.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]