Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a potentially serious disorder attacking millions of people around the world. Many of these individuals are undiagnosed, and even though diagnosed often exhibit a poor compliance with the use of continuous positive airway pressure at nights, a very effective nonsurgical treatment. A variety of surgical procedures have been proposed to manage and treat OSA. This article throws insights into assessing the sites of obstruction and a number of surgical procedures designed to address OSA. The scope of this article is to provide information to dentists which enables them to identify the patients who have OSAS and to guide these patients in making informed decisions regarding treatment options.

Keywords: Apnea, obstructive sleep apnea, sleep, snoring

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a sleep-concerned breathing disorder that involves a decrease or complete stop in airflow in spite of an ongoing effort to breathe, which is a result of relaxation of the pharyngeal muscles. Majority of people with OSA snore loudly and frequently, with periods of pause when airflow is reduced or blocked.[1,2] They then have choking, snorting, or gasping sounds when their airway resumes during sleep, causing soft tissue in the back of the throat to collapse and obstruct the upper airway. The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is 4% in men whereas 2% in women among middle-aged population.[3] As age increases, the prevalence also rises and is estimated around 28%–67% for elderly men and 20%–54% for elderly women.[4]

CLASSIFICATION

Mild OSA: (apnea–hypopnea index [AHI] of 5–15) – Involuntary sleepiness at times of activities that demand little attention, such as watching TV or reading

Moderate OSA: (AHI of 15–30) – Involuntary sleepiness during activities that need some attention, such as meetings or presentations

Severe OSA: (AHI of >30) – Involuntary sleepiness during activities that need more attention such as talking or driving.

SYMPTOMS

SIGNS TO IDENTIFY PATIENTS AT RISK OF APNEA

Increased daytime sleepiness – drowsy driving

Automobile or work-related accidents due to fatigue

Personality changes or cognitive difficulties related to fatigue

Hypertension

Nasopharyngeal narrowing

Pulmonary hypertension (rarely).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

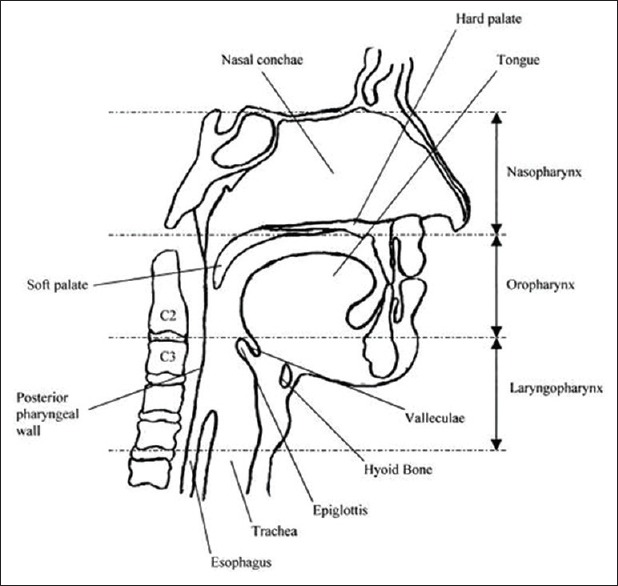

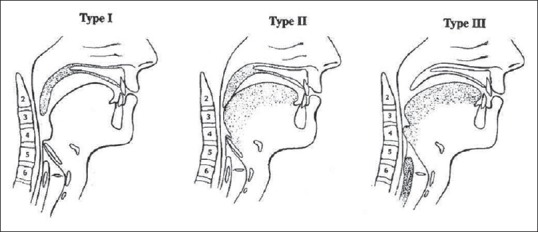

The major factors that play a potential role in the development of OSA are: (i) decrease in the forces of the pharyngeal dilators, (ii) the negative inspiratory pressure generated by the diaphragm, and (iii) improper upper airway anatomy, the element most effectively addressed by surgery.[8] The common sites of obstruction are located in the pharynx.[9] Airway failure often occurs when patients sleep on their back and the base of the tongue adheres to the posterior pharyngeal wall and soft palate. Elongated or excessive tissue of the soft palate, a large tongue, swollen uvula, large tonsils, and redundant pharyngeal mucosa are the most common reasons of snoring and OSA. The accomplishment of airway surgery depends on an appropriate diagnosis of the sites of obstruction and the perfect selection of procedures to address these sites [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Anatomy of sleep apnea

Figure 2.

Sites of obstruction

TESTS TO DETERMINE OBSTRUCTION OF SLEEP

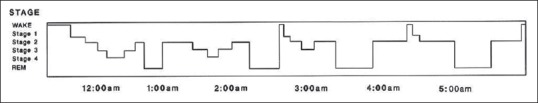

Currently, polysomnography, which requires a sleepover in a laboratory, is the optimum test for diagnosing sleep apnea. It involves the evaluation of sleep staging [Figure 3], airflow and ventilatory effort, arterial oxygen saturation, electrocardiogram, body position, and periodic limb movements. Polysomnography is not always readily available. Alternative methods to consider are evaluation using pulse oximetry and portable (home) monitoring of cardiopulmonary channels.[10]

Figure 3.

Evaluation of sleep chart

MANAGEMENT

OSAS can be managed nonsurgically or surgically. The treatment modality should focus on the potential contributing factors identified by the history, physical examination, and upper airway imaging. The severity of the patient's condition must also be taken into consideration in developing a treatment plan. Since obesity is a risk factor for OSAS, a weight loss program can reduce sleep apnea.[11]

NONSURGICAL METHODS

Continuous positive airway pressure

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the gold standard treatment option for moderate-to-severe cases of OSA and a better option for mild sleep apnea.[12] The first treatment of sleep apnea was introduced in 1981; CPAP provides a steady stream of pressurized air to patients through a mask that they wear.

Oral appliances

Oral or dental appliances may be the choice for patients with mild-to-moderate sleep apnea. However, they are not a remedy for all patients. This airflow maintains the airway open, preventing pauses in breathing and restoring normal oxygen levels. Novel CPAP models are small, light, and virtually silent. A variety of devices that move the tongue forward or move the mandible to an anterior and forward position to improve patency of the airway have been marketed.[13]

Oral appliances are preferred to people with mild-to-moderate OSA who either prefer it than CPAP or they are not able to successfully comply with CPAP therapy. Oral appliances resemble much like sports’ mouth guards, and they aid in maintaining an open and unobstructed airway by repositioning or stabilizing the lower jaw, tongue, soft palate, or uvula. Some are specifically designed for snoring and others are planned to treat both snoring and sleep apnea.

SURGICAL TREATMENT METHODS

Tracheotomy is the primary treatment modality for OSA and a temporary measure during other surgical procedures where airway cannot be maintained through oro-nasal routes. Thatcher and Maisel state that tracheostomy leads to quick reduction in sequelae of OSA and results in only a very few complications.[14]

The initial methods used were surgical and upper airway reconstructive or bypass procedures. Bypass procedure comprises nasal procedures which include septoplasty, functional rhinoplasty, nasal valve surgery, nasal polypectomy, and endoscopic procedures.

Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal procedures include uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, palatal advancement pharyngoplasty, tonsillectomy, and excision of tori mandibularis.

Hypopharyngeal procedures include tongue reduction, partial glossectomy, lingual tonsillectomy, and mandibular advancement. Laryngeal procedures include epiglottoplasty and hyoid suspension. Global airway procedure consists of maxillo-mandibular advancement bariatric surgery. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty is the most widely performed surgery for OSA. Friedman et al. showed a success rate in a period of 6 months to be 80% in selected patients.[15]

CONCLUSION

OSAS is a condition that results in significant morbidity and mortality. Hence, dentists must be aware of the signs and symptoms of OSAS such that they can confirm the diagnosis, and treatment can be initiated at the appropriate time. In patients with anatomic abnormalities of the maxilla and mandible resulting in a narrow pharyngeal airway, orthognathic surgery proves to be an excellent choice of treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ephros HD, Madani M, Yalamanchili SC. Surgical treatment of snoring; obstructive sleep apnoea. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:267–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sojot AJ, Meisami T, Sandor GK, Clokie CM. The epidemiology of mandibular fractures treated at the Toronto general hospital: A review of 246 cases. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:640–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodday RH. Nasal respiration, nasal airway resistance, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1997;9:167–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffestein V, Szalai J. Predictive value of clinical features in diagnosing obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep. 1993;16:118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millman RP, Carlisle CC, McGarvey ST, Eveloff SE, Levinson PD. Body fat distribution and sleep apnea severity in women. Chest. 1995;107:362–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies RJ, Stradling JR. The relationship between neck circumference, radiographic pharyngeal anatomy, and the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1990;3:509–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ephros HD, Madani M, Yalamanchili SC. Surgical treatment of snoring; obstructive sleep apnoea. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:267–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuna ST, Sant’Ambrogio G. Pathophysiology of upper airway closure during sleep. JAMA. 1991;266:1384–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gyulay S, Olson LG, Hensley MJ, King MT, Allen KM, Saunders NA, et al. A comparison of clinical assessment and home oximetry in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:50–3. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loube DI, Loube AA, Mitler MM. Weight loss for obstructive sleep apnea: The optimal therapy for obese patients. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:1291–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)92462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981;1:862–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt-Nowara W, Lowe A, Wiegand L, Cartwright R, Perez-Guerra F, Menn S, et al. Oral appliances for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: A review. Sleep. 1995;18:501–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thatcher GW, Maisel RH. The long-term evaluation of tracheostomy in the management of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:201–4. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:13–21. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.126477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]