Abstract

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis. The clinical presentation of LPP may mimic bullous pemphigoid making the diagnosis difficult. A thorough clinical, histopathological, and immunological evaluation is essential for the diagnosis of LPP. The etiology is largely idiopathic; however, there are several case reports of drug-induced LPP. We report an 81-year-old Thai woman with underlying hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus who presented with a 4-week history of multiple tense bullae initially on the hands and feet that subsequently expanded to the trunk and face. Enalapril was commenced to control hypertension. The histopathology and direct immunofluorescence were compatible with LPP. Circulating anti-basement antibodies BP180 was also positive. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroid with a modest effect. Enalapril was discontinued and complete resolution of LPP occurred within 12 weeks. There was no recurrence after a 1-year follow-up period. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first case of enalapril-induced LPP. Early recognition and prompt discontinuation of the culprit drug allow resolution of the disease. Medication given for LPP alone, without cessation of the offending drug, may not change the course of this condition.

Keywords: Bullous pemphigoid, Enalapril, Lichen planus, Lichen planus pemphigoides

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old Thai woman with a medical history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus visited Ramathibodi hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, with multiple erosions of 4 weeks' duration. The patient developed blisters on the hands and feet that subsequently expanded to involve the trunk and face. Blisters and erosions occurred on sites of previously uninvolved skin. She also complained of losing both big toe nails. She denied a history of fever, arthralgia, photosensitivity, and a previous or current dermatological condition. Her hypertension and type 2 diabetes had been well-controlled with amlodipine, enalapril, hydrochlorothiazide, and metformin for 6 years. Multiple erosions on erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques on the face, both ears, right axilla, abdomen, distal fingers, and toes with anonychia of both toe nails. Some erosion arose on the normal appearing skin (Fig. 1). Histological examination demonstrated subepidermal vesicle with well-preserved dermal papilla associated with dense inflammatory cell infiltration composed of lymphocytes and numerous eosinophils in the papillary dermis. The appearances suggested a subepidermal blistering with lichenoid eruption. A second biopsy on the perilesional skin was done for direct immunofluorescence examination and revealed linear immunoglobulin (Ig) G and C3 deposition along the dermoepidermal junction associated with shaggy deposition of fibrinogen and colloid body of IgM (Fig. 2). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for circulating anti-basement antibodies bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 was positive with a titer of 72.4 (normal value 0–22) and antibody for BP230 was negative. Anti-hepatitis C and hepatitis B antigen were negative. Based on the clinical examination, complete histological and immunological findings as well as the positive ELISA for BP180, the diagnosis of lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) was made.

Fig. 1.

Multiple erosions on erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques involving bilateral ears (a, b), abdomen (c), distal fingers (d), and toes with anonychia of both toe nails (e).

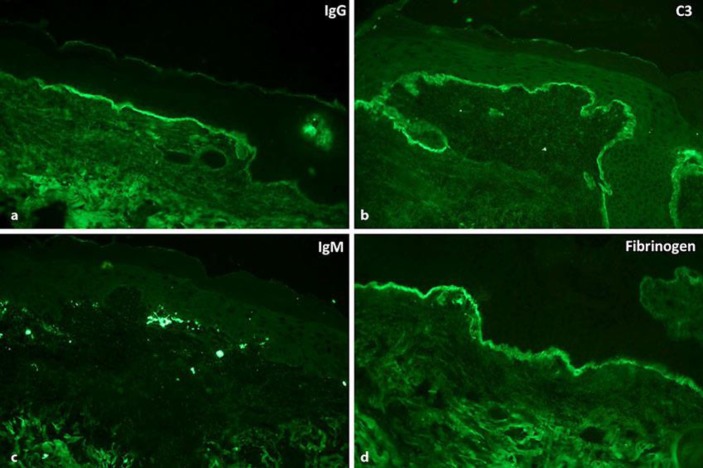

Fig. 2.

Linear IgG (a) and C3 (b) along the dermoepidermal junction. Moderate cytoid body IgM (c) associated with shaggy deposition of fibrinogen (d) along the dermoepidermal junction.

Clobetasol proprionate cream 0.05% was commenced for the trunk, extremities, and nails and momethasone furoate cream 0.1% for the face without any improvement. Then, enalapril was discontinued, and 4 weeks later the patient's condition moderately improved and was completely cleared at 12 weeks. There was no recurrence after a 12-month follow-up period (Fig. 3). The temporal relationship between the use of enalapril and the resolution of the disease upon withdrawal led us to the diagnosis of LPP as a reaction to enalapril.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the patient's condition before (a) and after (b) treatment.

Discussion

LPP is a rare, acquired autoimmune bullous dermatosis. It was introduced by Kaposi in 1982 as a typical case of lichen planus complicated by widespread bullous eruption [1]. The diagnosis of LPP is made by characteristic clinical, histopathological, and immunopathological features.

Clinically, LPP is characterized by an abrupt onset of tense, dome-shaped bullae prior to, during, or after an eruption of lichen planus. The blisters may arise on uninvolved skin or on preexisting lichenoid lesions [2]. In LPP the lesions most commonly involve the distal extremities, but they may occur in a generalized form. Oral and conjunctival mucosa involvement has been reported [3]. LPP more commonly affects males, usually in the fourth or fifth decade of life [3].

Histopathologically, LPP is characterized by typical findings of lichenoid tissue reaction with subepidermal bullae and linear deposits of IgG and C3 along the basement membrane zone (BMZ) on direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of peribullous skin [4]. This patient fulfilled the clinical, histological, and immunofluorescent criteria of LPP. Furthermore, in this patient, DIF revealed classic findings of continuous linear deposition of C3 and IgG and shaggy deposition of fibrinogen along the BMZ.

The pathogenesis of LPP is incompletely elucidated. Some authors hypothesized that a primary inflammatory process by lichen planus causes the release and exposure of hidden antigen leading to a secondary autoimmune response against the BMZ. These circulating autoantibodies induce secondary subepidermal bullous dermatosis. Many cases of LPP reported in the literature have demonstrated IgG antibodies to either one or both BP180 and BP230 antigens [4]. Zillikens et al. [4] demonstrated antibody reactivity in LPP against a novel epitope of region 4 of the NC16A domain of BP180 antigen besides regions 2 and 3.5. This finding was not demonstrated in sera from patients with BP, which indicates that the immunological pattern in LPP differs from that in patients with BP [4]. BP180 ELISA using a commercial kit was positive in our patient.

LPP has been reported to be induced by medications such as angiotensin-converting- enzyme inhibitors (captopril [5, 6], ramipril [7, 8]), cinnarizine [9], PUVA [10], simvastatin [11], Chinese herb [12], weight reduction product [13], and NB-UVB [14]. The interval between drug administration and occurrence of LPP ranged from 2 to 24 weeks. Like drug-induced lichen planus and lichenoid drug reaction, an extended time interval between the initiation of the drug to the onset of symptoms does not exclude a potential diagnosis of drug-induced LPP [15]. For most patients, the skin eruptions resolved within a few weeks after withdrawal of the drug (Table 1). The definitive proof of diagnosis is recurrence on challenge, but this is not always possible or desirable.

Table 1.

Drug associated with lichen planus pemphigoides

| Medications | Authors [Ref.], year | Onset | Cutaneous distribution | Mucosa | Additional treatment | Time of resolution and recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitor - Enalapril - Captopril - Ramipril |

Our case | 6 years | Trunk, extremities | No | Topical steroid | 12 weeks, no recurrence after 1-year follow-up |

| Flageul et al. [6], 1986 | 2 weeks | Extremities | No | Topical steroid | Not completely resolved at 10-month follow-up | |

| Ben Salem et al. [5], 2008 | 2 weeks | Trunk, extremities | No | Systemic steroid | 4 weeks, no recurrence after 8-month follow-up | |

| Ogg et al. [7], 1996 | 4 weeks | Trunk, extremities | No | Systemic steroid | 9 weeks, no recurrence after 1-year follow-up | |

| Zhu et al. [8], 2006 | 3 weeks | Trunk, extremities | Yes | No | 4 weeks | |

| Cinnarizine | Miyagawa et al. [9], 1985 | 12 weeks | Lower extremities then trunk | No | Griseofulvin | 12 weeks |

| PUVA | Kuramoto et al. [10], 2000 | 24 weeks | Trunk, extremities | No | Systemic and topical steroid | 4 weeks, no recurrence after 1-year follow-up |

| Simvastatin | Stoebner et al. [11], 2003 | 4 weeks | Trunk, extremities | No | Topical steroid | 4 weeks |

| Chinese herb | Xu et al. [12], 2008 | 8 weeks | Trunk, extremities | Yes | Systemic steroid and dapsone | Not completely resolved at 2-year follow-up (remains on dapsone and intermittent topical steroids) |

| Weight reduction product | Rosmaninho et al. [13], 2011 | 8 weeks | Trunk, extremities | No | Dapsone | 4 weeks, no recurrence during 1-month follow-up |

ACE; angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Low to moderate doses of oral corticosteroid seems to be effective in the majority of patients with LPP. In some cases, topical corticosteroid administration alone was shown to be effective. There is little information about therapy with other immunosuppressant drugs or combination with corticosteroid for LPP [3]. In our case, a potent topical corticosteroid was not effective. The patient had gradual improvement and established complete resolution upon cessation of the culprit medication.

The prognosis of LPP tends to be better compared to BP and lichen planus. The average rate of recurrence was about 20% and the response after treatment was about 1–12 months, which appears to be lower when compared to BP and lichen planus.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of enalapril associated with the development of LPP. Early recognition and prompt discontinuation of the possible medication allows improvement of the clinical outcome and prevents further complications.

Statement of Ethics

We state that our patient gave informed consent. The research complies with all ethical guidelines for human studies.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. There was no funding for this work.

References

- 1.Kaposi M. Lichen ruber pemphigoides. Arch J Dermatol Syph. 1892;24:343–346. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamada Y, Yokochi K, Nitta Y, Ikeya T, Hara K, Owaribe K. Lichen planus pemphigoides: identification of 180 kd hemidesmosome antigen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:883–887. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, Chelly I, El Euch D, Zitouna M, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, Wesselmann U, Schmidt E, Prost C, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben Salem C, Chenguel L, Ghariani N, Denguezli M, Hmouda H, Bouraoui K. Captopril-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:722–724. doi: 10.1002/pds.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flageul B, Foldes C, Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Cottenot F. Captopril-induced lichen planus pemphigoides with pemphigus-like features. A case report. Dermatologica. 1986;173:248–255. doi: 10.1159/000249262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogg GS, Bhogal BS, Hashimoto T, Coleman R, Barker JN. Ramipril-associated lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu YI, Fitzpatrick JE, Kornfeld BW. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with ramipril. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1453–1455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyagawa S, Ohi H, Muramatsu T, Okuchi T, Shirai T, Sakamoto K. Lichen planus pemphigoides-like lesions induced by cinnarizine. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:607–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb15272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, Yasuno H. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoebner PE, Michot C, Ligeron C, Durand L, Meynadier J, Meunier L. Simvastatin-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu HH, Xiao T, He CD, Jin GY, Wang YK, Gao XH, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with Chinese herbs. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:329–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosmaninho A, Sanches M, Oliveira A, Alves R, Selores M. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by a weight reduction drug. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:306–308. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2011.566234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandy Chan WM, Lee JS, Thiam Theng CS, Chua SH, Boon Oon HH. Narrowband UVB-induced lichen planus pemphigoide. Dermatol Reports. 2011;3:e43. doi: 10.4081/dr.2011.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sin B, Miller M, Chew E. Hydrochlorothiazide induced lichen planus in the emergency department. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30:266–269. doi: 10.1177/0897190016630879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]