Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Individuals with diverticulosis frequently also have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but there are no longitudinal data to associate acute diverticulitis with subsequent IBS, functional bowel disorders, or related emotional distress. In patients with postinfectious IBS, gastrointestinal disorders cause long-term symptoms, so we investigated whether diverticulitis might lead to IBS. We compared the incidence of IBS and functional bowel and related affective disorders among patients with diverticulitis.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective study of patients followed up for an average of 6.3 years at a Veteran’s Administration medical center. Patients with diverticulitis were identified based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision codes, selected for the analysis based on chart review (cases, n = 1102), and matched with patients without diverticulosis (controls, n = 1102). We excluded patients with prior IBS, functional bowel, or mood disorders. We then identified patients who were diagnosed with IBS or functional bowel disorders after the diverticulitis attack, and controls who developed these disorders during the study period. We also collected information on mood disorders, analyzed survival times, and calculated adjusted hazard ratios.

RESULTS

Cases were 4.7-fold more likely to be diagnosed later with IBS (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6–14.0; P < .006), 2.4-fold more likely to be diagnosed later with a functional bowel disorder (95% CI, 1.6–3.6; P < .001), and 2.2-fold more likely to develop a mood disorder (CI, 1.4–3.5; P < .001) than controls.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with diverticulitis could be at risk for later development of IBS and functional bowel disorders. We propose calling this disorder postdiverticulitis IBS. Diverticulitis appears to predispose patients to long-term gastrointestinal and emotional symptoms after resolution of inflammation; in this way, postdiverticulitis IBS is similar to postinfectious IBS.

Keywords: Outcome, Colon, Inflammatory Disorder, Functional Gastrointestinal Disease

Diverticular disease imposes a significant burden on Western and industrialized societies.1,2 The prevalence of diverticulosis increases with age, affecting 70% of individuals aged 80 years or older in the United States.1,2 Up to 1 in 4 patients with diverticulosis experiences an inflammatory or infectious complication, including diverticulitis, peritonitis, or abscess formation.3,4 These complications account for more than 300,000 hospital admissions, 1.5 million inpatient days, and $2.4 billion in direct costs annually in the United States.1,2,5 The prevalence of diverticular disease will increase with an aging and an expanding population.6

Although diverticular disease often is conceived as abrupt, disruptive, and comprising acute diverticulitis attacks surrounded by periods of clinical silence, this is not true for everyone. Recent studies have reframed the paradigm of diverticular disease from an acute surgical illness to a chronic disorder with symptoms persisting long after acute complications subside.7–11 This form of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease implies that chronic gastrointestinal symptoms co-occur with diverticulosis in the absence of overt complications or macroscopic inflammation.7–11 Research in symptomatic diverticular disease suggests a potential role for low-grade peridiverticular inflammation.9,12 Evolving research implicates altered motility reminiscent of “spastic colon,”13 diverticular-related visceral hypersensitivity,9,14 and altered intestinal micro-biota15 in a pathophysiologic picture similar to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a condition marked by the same underlying mechanisms of inflammation,16 dysmotility,17 hyperalgesia,18,19 and dysbiosis.20

The pathophysiologic overlap between diverticular disease and IBS is supported by surveys showing concurrence between diverticulosis and IBS symptoms. In a cross-sectional survey of patients with colonic diverticular disease, Jung et al7 found that 17% of diverticulosis subjects had frequent lower abdominal pain and 29% had altered bowel habits, rates significantly higher than nondiverticulosis controls. Simpson et al10 found that 71% of patients experienced recurrent, long-standing abdominal pain after an attack vs only 34% of diverticular patients without an attack. Although these studies show important epidemiologic associations between diverticular disease and functional bowel symptoms, they cannot assert a temporal relationship. Beyond bowel symptoms, studies also have found that symptomatic diverticular disease is associated with diminished health-related quality of life, especially vitality and emotional health.21,22 Taken together, these results indicate that diverticular disease may become a chronic illness marked by ongoing bowel symptoms and psychosocial distress. However, previous studies have been cross-sectional; it remains unknown whether the relationship between diverticular disease and IBS is causal, or merely associative.

To further explore the possibility of postdiverticulitis IBS (PDV-IBS), we conducted a longitudinal study comparing the risk of developing new IBS and related functional bowel diseases in diverticulitis cases vs controls. We bolstered these analyses by tracking new depression and mood disorders after the diverticulitis attack. We hypothesized that, as in postinfectious IBS (PI–IBS),23 patients who experienced an acute diverticulitis attack would show a higher incidence of chronic bowel symptoms and psychosocial distress vs controls.

Methods

Data Source

To study the longitudinal relationship between acute diverticulitis and PDV-IBS, we performed a retrospective case vs control survival analysis using administrative and clinical data from the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS). VAGLAHS maintains electronic medical records from 14 community clinics and 1 inpatient academic medical center: the West Los Angeles VA. The VAGLAHS database includes patient demographics, inpatient and outpatient treatment files, and laboratory, imaging, pathology, and pharmacy data.

Selection of Diverticulitis Cases

We queried the VAGLAHS database for inpatient or outpatient International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes for diverticulitis and its complications, including diverticulitis (ICD-9 code: 562.11), diverticular abscesses (ICD-9 code: 569.5), and diverticular perforations (ICD-9 code: 569.83). We performed diagnostic coding corroboration through medical record review. Physician abstractors used a standardized chart review including automated natural language searching of provider notes for relevant keywords (eg, “diverticulitis,” “diverticular disease”), and assessment of laboratory, imaging, and pathology records. For inclusion, we required a formal chart diagnosis of diverticulitis by a treating physician, based on clinical parameters (eg, leukocytosis, fever), and/or radiographic or surgical specimens. We categorized each case based on the clinical level of evidence used to make the diagnosis. Clinical assessment and laboratory data were assigned lower levels of evidence, whereas computed tomography (CT) or surgically confirmed cases were assigned the highest levels of evidence. All cases received a course of oral or parenteral antibiotics.

We excluded cases in which a chart review failed to identify a physician diagnosis based on clinical parameters. In addition, we excluded subjects with pre-existing diagnoses suggesting a history of gastrointestinal symptoms before the diverticulitis index date. Specifically, we excluded patients with pre-existing diagnostic codes for IBS (ICD-9 code: 564.1) and related functional bowel disease diagnoses including spastic colon, functional diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain (ICD-9 codes: 564.X, 789.X, and 306.4). Moreover, because psychiatric disease has been known to be a risk factor for IBS, we also excluded patients with ICD-9 codes 296.2 (major depressive disorder) and 300.4 (dysthymic disorder) and related variants. The purpose of these exclusions was to focus our analysis on new IBS diagnoses after the index attack.

We further excluded patients with codes for other gastrointestinal disorders, including peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and gastrointestinal malignancies. The purpose of these exclusions was to ensure the outcome of interest (new IBS diagnoses) was valid because these exclusionary diagnoses are either incompatible with or undermine the diagnosis of IBS.

Selection of Controls

For each diverticulitis case, we identified an age (±1 y), sex, and inpatient vs outpatient-matched control who sought care on the same day as the diverticulitis case, but who did not have a diverticulitis code. We randomly selected controls through incidence density sampling with replacement. On chart review, controls that did not meet the clinical assessment of diverticulitis were included.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: postdiverticulitis irritable bowel syndrome

The primary outcome was a new IBS diagnosis after the index diverticulitis attack (for cases) or enrollment date (for controls). We defined IBS as acquisition of ICD-9 code 564.1. To validate IBS diagnoses, we conducted a manual chart audit of all subjects who acquired the IBS code during the observation period. We performed a review of progress notes, prescription records, and endoscopy, surgery, radiology, microbiology, and pathology reports for each subject during the 12 months before and after the ICD-9 code was assigned. Previously identified criteria for IBS have been developed.24 In practice, IBS is diagnosed using the Rome criteria25: a case-finding definition designed for clinical trials rather than retrospective chart reviews. Given the limitations of relying on database records, we used pragmatic modified criteria incorporating Rome and administrative definitions.

We made a chart-confirmed diagnosis of IBS if the patient: (1) showed no clinical or objective evidence of organic intestinal pathology, including malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal infection, or celiac sprue; (2) showed no alarm signs or symptoms, including unintended weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, or evidence of anemia; and (3) reported symptoms consistent with Rome criteria for IBS, including both recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort and repeated defecatory symptoms, including constipation or diarrhea, for a minimum duration of 6 months. We applied these criteria to all ICD-9 –positive instances of IBS. To further validate IBS diagnoses, we pulled a 20% random sample of subjects without an IBS ICD-9 code and sought evidence for IBS from chart review. After stratifying coded and chart-confirmed diagnoses, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for the ICD-9 IBS code in our population.

Secondary outcomes

In addition to new IBS diagnoses, we also tracked acquisition of ICD-9 codes for related functional bowel diseases including spastic colon, functional diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain (ICD-9 codes: 564.X, 789.X, and 306.4). Finally, in light of data that diverticulitis can trigger long-term decrements in emotional health,21,22 we measured new diagnoses of depression and related mood disorders (ICD-9 series: 296.XX).

Statistical Analyses and Power Calculation

We generated frequencies for baseline population characteristics, and compared these values using chi-square testing for numeric variables, and Student t tests for continuous variables. We then performed time-to-event survival analyses with right censoring if subjects: (1) developed IBS; (2) died; (3) were lost to follow-up evaluation; or (4) or were still present by the end of the follow-up period (January 1, 2012). We then performed a Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, sex, inpatient vs outpatient status, and comorbidity, as measured by the Deyo adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity score.26 We tested the proportional-hazards assumption and used the likelihood-ratio test in the Cox models to evaluate the significance of the observed differences in survival functions between cases and controls. To power a model with 10 potential independent variables, we required a minimum of 20 observations per variable, or 200 subjects, to test the independent relationship between diverticulitis exposure and IBS. In all tests, we considered a P value of less than .05 significant. We performed statistical analyses with SAS Statistical Software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The VAG-LAHS institutional review board approved this study (Project Coordinating Center #0016).

Results

Patient Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

We found 3992 patients with ICD-9 codes for diverticular disease and 1105 had chart-confirmed diverticulitis. Of those with diverticulitis, a subset of 326 were diagnosed based on either CT or surgical confirmation. An equal number of age, sex, and inpatient vs outpatient matched controls were selected randomly. Table 1 provides key characteristics of the sample. Cases and controls were distributed similarly along demographic variables. The mean follow-up period was 6.3 years (median, 3.4 y; range, 0.3–9.0 y).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Diverticulitis cases (n ± 1102) | Matched controls (n ± 1102) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y | 62.2 ± 12.5 | 62.2 ± 13 |

| Sex, % male | 95.6 | 95.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 38.2% | 46.9% |

| Black | 21.2% | 11.1% |

| Hispanic | 6.6% | 8.4% |

| Other or missinga | 34.0% | 33.6% |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.5 ± 2.1 | 1.1 ± 1.8 |

| Person-years of follow-up evaluation | 7051 | 6935 |

Patients are not required by the Veterans Administration to provide their race or ethnicity. Missing cases represent patients who prefer not to report this information.

Validity of Primary Outcome

There were 24 cases of newly diagnosed IBS during the study period: 20 in cases, and 4 in controls. Chart review confirmed that 23 of the 24 cases met prespecified diagnostic criteria. The subsequent analyses excluded the false case. Among 240 subjects from the validation cohort without an IBS ICD-9 code, only 1 subject met criteria for IBS. This yielded an IBS code sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 95.8%, 99.2%, 92%, and 99.6%, respectively.

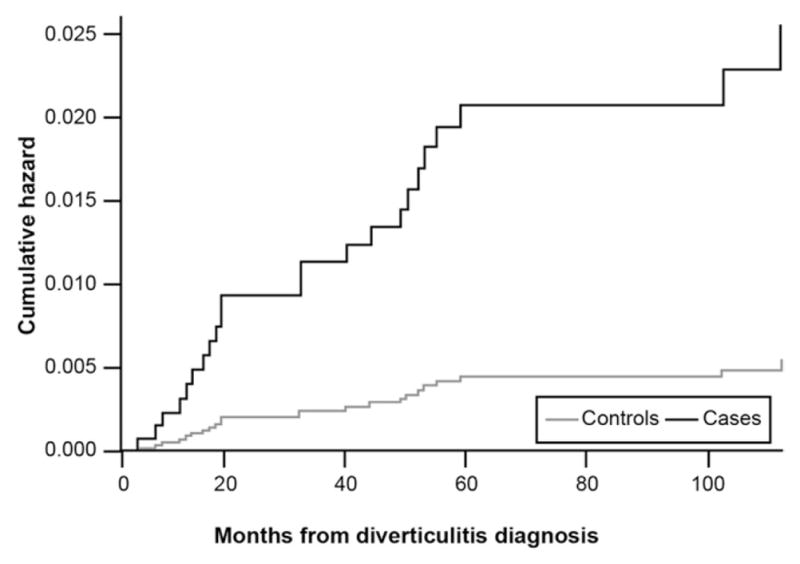

Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Cases vs Controls

Figure 1 presents survival curves extending out 9 years for incident IBS diagnoses in diverticulitis cases vs matched controls. In unadjusted survival analysis, cases were 4.6 times more likely to acquire an IBS code during the observation period vs controls (hazard ratio [HR], 4.6; 95% confidence intervals [CI], 1.6 –13.6; P = .005). After adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, race, inpatient vs outpatient status, and comorbidity score the cases remained more likely to receive an IBS code (HR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.6 –14.0; P = .006).

Figure 1.

Incidence of new IBS diagnoses in diverticulitis cases vs matched controls.

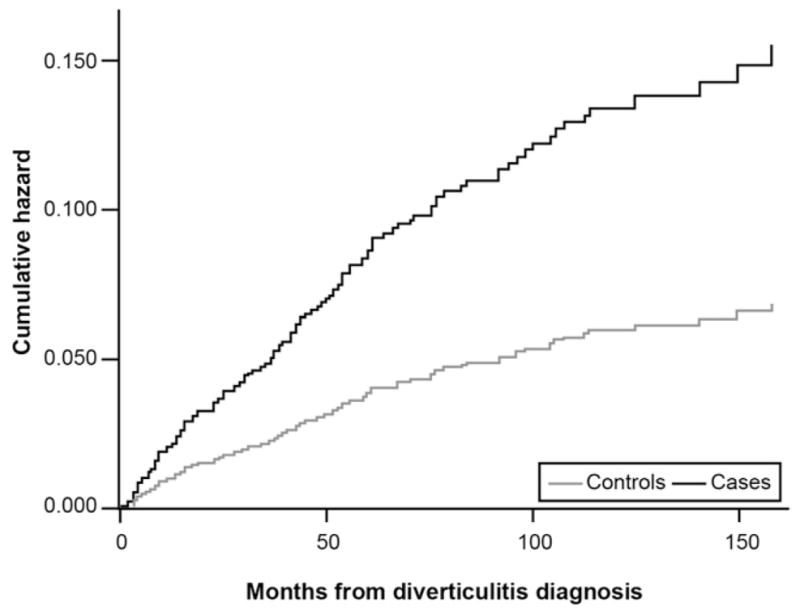

Secondary Outcomes in Cases vs Controls

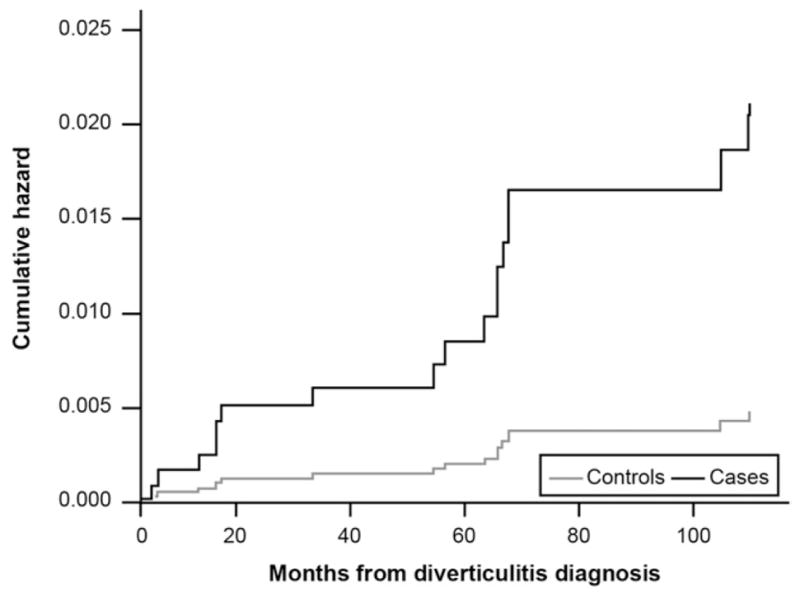

Figure 2 presents survival curves for new functional gastrointestinal disorder codes in diverticulitis cases vs controls. There were 146 new functional gastrointestinal diagnoses: 95 in cases, 51 in controls. Cases were 2.3 times more likely to receive any functional bowel disorder code vs controls (HR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6 –3.3; P < .001). This difference remained significant after adjustment for covariates (HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6 –3.6; P < .001). Figure 3 presents the curves for a new diagnosis of depression and related mood disorders. When focusing on the cases confirmed by either CT or surgical resection, there were 12 new diagnoses of functional gastrointestinal disorder codes: 11 in cases, 1 in controls; the difference remained highly significant (HR, 11.7; 95% CI, 1.5–246; P = .005). There were 98 new diagnoses of mood-disorder diagnoses: 63 in cases, 35 in controls. Cases remained more likely to acquire a mood disorder diagnosis vs controls in both unadjusted (HR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.2–3.0; P = .007) and adjusted (HR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.4 –3.6; P < .001) analyses.

Figure 2.

Incidence of new functional bowel disorder diagnoses in diverticulitis cases vs matched controls.

Figure 3.

Incidence of new depression and mood disorder diagnoses in diverticulitis cases vs matched controls.

Discussion

Previous research documented an association between diverticular disease and chronic gastrointestinal symptoms.7,10,11 Because these studies were cross-sectional, it remains unclear whether the relationship between conditions is causal or merely associative. We conducted a longitudinal analysis comparing new IBS and functional bowel diagnoses in a large sample of chart-confirmed diverticulitis cases vs controls. After excluding patients with pre-existing IBS or functional bowel diagnoses, we found that diverticulitis patients were 4.7 and 2.4 times more likely than controls to be diagnosed with IBS or a functional bowel disorder, respectively, after experiencing their attack.

It is possible that diverticulitis patients in this study were simply misdiagnosed as having IBS, or vice versa. However, 3 observations undermine this assertion. First, we excluded patients with pre-existing IBS and functional bowel diagnoses. The high background prevalence of IBS in Western populations confounds previous work on the natural history of diverticular disease. We then found a higher incidence of new diagnoses in chart-confirmed diverticulitis cases vs matched controls. This temporal relationship suggests that the IBS and functional bowel diagnoses followed the index attack, and not the other way around. Moreover, if we adopt the null hypothesis, we would expect no systematic differences in the reporting of any long-term functional symptoms between cases and controls. Although ICD-9 codes can be an insensitive diagnostic appraisal of IBS or diverticulitis, cases were confirmed by extensive physician chart review. The strength of our diagnostic validation process, as measured by traditional test metrics, bolsters this view. Nonetheless, this study was retrospective, so it remains impossible to definitively confirm the relationship.

Second, Figure 1 reveals that the curves did not fully diverge until 10 months after the index enrollment dates and persisted for months after, whereas rates for the controls plateaued. Chronic abdominal pain and persistent alterations in bowel habits—the hallmarks of the Rome criteria for IBS—are atypical for the usually short-lived functional abdominal pain that can accompany acute diverticular attacks. This suggests that IBS was not simply diagnosed in and around the time of the diverticulitis attack, but was identified in the months and years after. Although this, too, cannot prove a causal link between diverticulitis and subsequent IBS, it provides further evidence that diverticulitis may have preceded IBS, and not vice versa. It further argues against a misclassification at the time of the index attack because one might expect new IBS diagnoses to occur closer to the index date in the case of misclassification, not in the months and years to follow.

Third, we supported these bowel symptom analyses by evaluating a related yet very different outcome—incident depression and related mood disorders. Because chronic bowel disorders are associated with depression, especially IBS,27 we hypothesized that diverticulitis cases would have a higher incidence of affective diagnoses vs matched controls; Figure 3 shows this finding. Coupled with finding a higher incidence of long-term chart-confirmed IBS and functional bowel diagnoses in cases vs controls, these results support the hypothesis that diverticulitis might trigger long-term physical and emotional symptoms well beyond the acute event.

The development of PDV-IBS is biologically plausible. Research has shown potentially shared pathophysiologic mechanisms between IBS and symptomatic diverticular disease. There are reports that some IBS patients show low-grade colonic inflammation in the absence of macroscopic colitis.5 Moreover, inflammation may alter gastrointestinal reflexes, amplify visceral sensitivity, render the bowel more susceptible to negative effects of microbiota, and alter motility in IBS.5 Similarly, some small studies have shown chronic microscopic inflammation in biopsy specimens taken from within and around diverticula in patients with symptomatic diverticular disease.12,28,29 Similar to IBS, patients with diverticular disease have heightened visceral pain perception in response to luminal distension compared with controls.8,14 Another putative mechanism of chronic diverticular disease involves shifts in intestinal microbiota leading to chronic inflammation, similar to theoretical models for IBS.20 Several lines of evidence support a potential association between the intestinal microbiota and diverticular disease. Gut-directed antibiotics may reduce attacks of recurrent diverticulitis and treat gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with symptomatic diverticular disease29,30; data also have shown modest benefits of antibiotics in IBS.31 Low dietary fiber intake, a putative risk factor for chronic diverticular disease and IBS with constipation, is also associated with alterations in the gut microbial composition32; these changes might lead to bacterial overgrowth or even precipitate acute diverticulitis.12 In a study of 90 patients with a history of acute diverticulitis, 60% met criteria for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth,15 a condition also purported to occur in many patients with IBS.20 Finally, there is a strong and consistent link between acute bacterial gastroenteritis and PI–IBS,23 a condition in which chronic bowel symptoms persist long after the infectious agent has cleared. Analogous to the postinflammatory model of PI–IBS, it is possible that acute diverticular inflammation may trigger PDV-IBS.

This study had several limitations. First, although we performed a longitudinal analysis, we cannot assert that diverticulitis caused IBS in this study. Although this study suggests directionality from diverticulitis to IBS, only a large prospective study can answer this question definitively. In the meantime, there is biological plausibility of a link, cross-sectional evidence from multiple previous studies, and now longitudinal evidence of a temporal relationship between diverticulitis and IBS. Second, we relied on administrative data to identify diverticulitis cases. These codes could have been applied inaccurately, and true cases may have been missed altogether. In fact, the diagnosis of diverticulitis in everyday clinical practice is often difficult because leukocytosis is not a requirement for diagnosis and CT scanning is not always performed. Thus, we used a pragmatic definition based on the same everyday clinical decisions made by providers on the front lines. However, when focusing just on those subjects with CT or surgically confirmed diverticulitis, the difference in new functional gastrointestinal diagnoses remained highly statistically significant. Future studies may better standardize the definition of diverticulitis in a prospective protocol. Last, our overall rate of IBS in this series was less than 1%; this is considerably lower than the 7% population prevalence quoted in IBS guidelines.33 However, IBS is generally more prevalent in younger women, and this series consisted almost entirely of men with an average age of 62 years. We also excluded pre-existing diagnoses of IBS, used the more restrictive Rome criteria, and solely focused on new diagnoses during the study period— generally rare diagnosis to accumulate de novo after the age of 60 in men.

Our findings support the evolving paradigm of diverticular disease as a chronic illness, not merely an acute condition marked by abrupt complications. Far from a self-limited episode, acute diverticulitis may become a chronic disorder in some patients. Diverticulitis is correlated with not only chronic IBS symptoms but also long-term emotional distress beyond the event itself. Awareness of this possible risk is important because persistent, untreated gastrointestinal symptoms and comorbid depression may worsen outcomes and increase the economic burden of an already prevalent disease. Existing diverticulitis guidelines largely focus on acute management principles rather than chronic symptoms.4,34 However, enhanced awareness of the potential long-term impact of diverticulitis, including the possibility of PDV-IBS, may allow for more timely diagnosis and treatment. Future research should identify demographic and clinical predictors of PDV-IBS and evaluate its incidence in prospective studies to better determine whether this link is causal or merely associative.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from Shire Pharmaceuticals. The principal investigators maintained all source data, SAS codes, and analytical files on site at the VA Medical Center.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

- HR

hazard ratio

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision

- PI-IBS

postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome

- PDV-IBS

postdiverticulitis irritable bowel syndrome

- VAGLAHS

Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

These authors disclose the following: Brennan Spiegel has served as an advisor for Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and has received research support from Amgen, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, and Shire Pharmaceuticals; and Linnette Yen, Paul Hodgkins, M. Haim Erder are employed by Shire Pharmacueticals. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the sole views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs.

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:741–754. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, et al. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks TG. Natural history of diverticular disease of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol. 1975;4:53–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stollman NH, Raskin JB. Diagnosis and management of diverticular disease of the colon in adults. Ad hoc practice parameters committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3110–3121. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozak LJ, DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. National hospital discharge survey: 2004 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital health Stat. 2006;13:1–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etzioni DA, Mack TM, Beart RW, Jr, et al. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann Surg. 2009;249:210–217. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181952888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, et al. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is associated with diverticular disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:652–661. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humes DJ, Simpson J, Neal KR, et al. Psychological and colonic factors in painful diverticulosis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:195–198. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humes DJ, Simpson J, Smith J, et al. Visceral hypersensitivity in symptomatic diverticular disease and the role of neuropeptides and low grade inflammation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:318–e163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson J, Neal KR, Scholefield JH, et al. Patterns of pain in diverticular disease and the influence of acute diverticulitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1005–1010. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200309000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson J, Scholefield JH, Spiller RC. Origin of symptoms in diverticular disease. Br J Surg. 2003;90:899–908. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horgan AF, McConnell EJ, Wolff BG, et al. Atypical diverticular disease: surgical results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1315–1318. doi: 10.1007/BF02234790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassotti G, Sietchiping-Nzepa F, De Roberto G, et al. Colonic regular contractile frequency patterns in irritable bowel syndrome: the ‘spastic colon’ revisited. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:613–617. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200406000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens CH, Samsom M, Roelofs J, et al. Colorectal visceral perception in diverticular disease. Gut. 2004;53:717–722. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, et al. Assessment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in uncomplicated acute diverticulitis of the colon. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2773–2776. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, et al. A role for inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome? Gut. 2002;51(Suppl 1):i41–i44. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camilleri M, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, et al. Prospective study of motor, sensory, psychologic, and autonomic functions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer EA, Collins SM. Evolving pathophysiologic models of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2032–2048. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertz H, Naliboff B, Munakata J, et al. Altered rectal perception is a biological marker of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:40–52. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin HC. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292:852–858. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolster LT, Papagrigoriadis S. Diverticular disease has an impact on quality of life–results of a preliminary study. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:320–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comparato G, Fanigliulo L, Aragona G, et al. Quality of life in uncomplicated symptomatic diverticular disease: is it another good reason for treatment? Dig Dis. 2007;25:252–259. doi: 10.1159/000103896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiller R, Campbell E. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:13–17. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000194792.36466.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yale SH, Musana AK, Kieke A, et al. Applying case definition criteria to irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Med Res. 2008;6:9–16. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2008.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trepsi E, Colla C, Panizza P, et al. Therapeutic and prophylactic role of mesalazine (5-ASA) in symptomatic diverticular disease of the large intestine. 4 year follow-up results. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 1999;45:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Daffinà R. Long-term treatment with mesalazine and rifaximin versus rifaximin alone for patients with recurrent attacks of acute diverticulitis of colon. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:510–515. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandimarte G, Tursi A. Rifaximin plus mesalazine followed by mesalazine alone is highly effective in obtaining remission of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:PI70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korzenik JR. Case closed? Diverticulitis: epidemiology and fiber. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(Suppl 3):S112–S116. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225503.59923.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein A, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 1):S1–35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong WD, Wexner SD, Lowry A, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis–supporting documentation. The Standards Task Force. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:290–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02258291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]