Abstract

Multiple lines of research have reported thalamic abnormalities in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) that are associated with social communication impairments (SCI), restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRB), or sensory processing abnormalities (SPA). Thus, the thalamus may represent a common neurobiological structure that is shared across symptom domains in ASD. Same-sex monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs with and without ASD underwent cognitive/behavioral evaluation and magnetic resonance imaging to assess the thalamus. Neurometabolites were measured with 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) utilizing a multi-voxel PRESS sequence and were referenced to creatine+phosphocreatine (tCr). N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), a marker of neuronal integrity, was reduced in twins with ASD (n=47) compared to typically-developing (TD) controls (n=33), and this finding was confirmed in a sub-sample of co-twins discordant for ASD (n=11). NAA in the thalamus was correlated to a similar extent with SCI, RRB, and SPA, such that reduced neuronal integrity was associated with greater symptom severity. Glutamate+glutamine (Glx) was also reduced in affected versus unaffected co-twins. Additionally, NAA and Glx appeared to be primarily genetically-mediated, based on comparisons between MZ and DZ twin pairs. Thus, thalamic abnormalities may be influenced by genetic susceptibility for ASD but are likely not domain-specific.

Keywords: autism, twins, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), thalamus, n-acetyl aspartate (NAA)

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders with recent estimates suggesting 1 in 68 children in the United States meet diagnostic criteria (CDC, 2014). ASD is a behaviorally defined disorder characterized by the presence of social communication impairments (SCI) and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior or interests (RRB) (APA, 2013). Symptom presentation and severity is highly variable, ranging from mild to severe, and may or may not be associated with intellectual impairment. Sensory processing abnormalities (SPA) are also commonly reported in individuals with ASD and were added to the most recent diagnostic criteria as a potentially affected domain (APA, 2013). Recent prevalence rates suggest that over three-quarters of individuals with ASD (76–90%) exhibit SPA (Klintwall et al., 2011; Leekam, Nieto, Libby, Wing, & Gould, 2007), the most common of which may be over-reactivity to sound (44%) or under-reactivity to pain (40%) (Klintwall et al., 2011). The clinical presentation of individuals with ASD is so variable that it is considered one of the most heterogeneous neuropsychiatric disorders.

Although the core symptoms of ASD were originally thought to be emergent from a common underlying mechanism, recent research has suggested ASD may reflect a dimensional disorder originating from impairments across independent domains (Mandy & Skuse, 2008). For example, autism-related traits are continuously distributed in the normal population (Constantino & Todd, 2003) but express low levels of covariation (Ronald et al., 2006a), even in individuals with the most severe impairments (Ronald, HappÉ, Price, Baron-Cohen, & Plomin, 2006b). Furthermore, it has been reported that one-half to two-thirds of the genes associated with SCI are not associated with RRB (Ronald et al., 2006a; Ronald, Happé, & Plomin, 2005). Thus, multifactorial genetic influences may independently contribute to specific behavioral outcomes; however, the effect of these genetic influences on neuronal development and their relationship with symptom presentations are not currently known. Investigations into the neurobiological basis of ASD suggest that there is most likely etiological heterogeneity, based on reports of widespread micro- and macro-structural abnormalities across the frontal, temporal, parietal, and cerebellar cortices with varying associations between these alterations and the core symptom domains, see review (Amaral, Schumann, & Nordahl, 2008)). Although independent brain-behavior relationships exist, there are also most likely common pathways and brain structures, such as the thalamus, that are shared between these potentially independent domains.

The thalamus stands out as a key processing component that may be related to the SCI, RRB, and SPA symptoms of ASD. The thalamus is reciprocally connected with the cortex through multiple processing streams and is involved in filtering almost all incoming sensory information. Multiple lines of research suggest thalamic abnormalities in ASD including reports of reduced neuronal density (Ray et al., 2005), altered thalamic volume (Hardan et al., 2006; Tamura, Kitamura, Endo, Hasegawa, & Someya, 2010; Tsatsanis et al., 2003), reduced integrity of thalamic radiations (Cheon et al., 2011; Nair, Treiber, Shukla, Shih, & Müller, 2013), reduced glucose metabolism (Haznedar et al., 2006), altered activation (Mizuno, Villalobos, Davies, Dahl, & Müller, 2006; Nair et al., 2013), and abnormal neurometabolite levels (Friedman et al., 2003; Hardan et al., 2008; Perich-Alsina, Aduna, Valls, & Muñoz-Yunta, 2002). Thalamic abnormalities are also associated with the core symptoms of ASD, including SCI (Nair et al., 2013; Tamura et al., 2010), RRB (Nair et al., 2013) and SPA (Hardan et al., 2008); however, these relationships have only been evaluated in separate samples utilizing different techniques (e.g., fMRI vs. MRS). Thus, the thalamus may represent a common neurobiological structure that is shared across symptom domains, but further research is necessary to determine the relationship between thalamic perturbations and SCI, RRB, and SPA.

A powerful approach for assessing brain-behavior relationships is the twin study design. Twin studies allow researchers to compare the influence of genetic versus environmental factors that contribute to a disorder and have been paramount in identifying the origins of individual differences in behavior. Twins discordant for a disorder also provide an especially powerful control comparison. Studies of monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs with ASD suggest a high rate of genetic influence, with concordance rates for ASD between 36–91% for MZ but 0–21% for DZ pairs (Bailey et al., 1995; Folstein & Rutter, 2006; Hallmayer et al., 2011; Steffenburg et al., 2006) and concordance rates for a broader dimensional definition of autism-related abnormalities between 77–92% for MZ but 10–31% for DZ pairs (Bailey et al., 1995; Hallmayer et al., 2011). Thus, ASD is a highly heritable disorder caused by genetic susceptibility towards disorder outcomes, but the neurobiological pathways affected by this genetic susceptibility are not yet known. To date, the application of the twin design into neurobiological studies of ASD has been limited (Mevel, Fransson, & Bölte, 2015); however, completed studies largely corroborate previous reports of alterations in the frontal (Kates et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2009), temporal (Kates et al., 2004), parietal (Kates, Ikuta, & Burnette, 2009), and cerebellar (Kates et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2009) cortices. Although informative, these investigations were primarily based on volumetric approaches (i.e., within a limited scope) and completed with relatively small sample sizes. Additionally, no previous twin studies of ASD have evaluated the thalamus.

In this investigation, we examine the relationship between thalamic abnormalities and SCI, RRB, and SPA in twins with and without ASD. 1H MRS approaches were utilized because these techniques have successfully identified thalamic abnormalities in independent samples of children with ASD (Hardan et al., 2008; Perich-Alsina et al., 2002), which suggested reduced neuronal integrity in this structure. Based on previous investigations by our (Hardan et al., 2008) and other groups (Friedman et al., 2003; Perich-Alsina et al., 2002), we hypothesized that thalamic N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) would be reduced in children with ASD compared to typically-developing (TD) controls and related to the core symptoms domains, especially SPA. Additionally, we predicted that NAA would exhibit significant genetic contributions, based on the only previous 1H MRS investigation in twins (Batouli et al., 2012); however, genetic influences may differ in ASD. Identifying the relationship between thalamic abnormalities and symptom domains will be an important step towards clarifying the neurobiological independence of clinical characteristics in ASD. Furthermore, utilizing a twin study design will provide important information regarding the potential genetic or environment factors that contribute to these neurobiological alterations.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

Same-sex twin pairs (male and female) between the ages of 6 and 15 years with at least one twin diagnosed with ASD (22 MZ and 32 DZ) and TD pairs (20 MZ and 15 DZ) were recruited from the California Autism Twin Study (Hallmayer et al., 2011) database, the Interactive Autism Network (a national autism registry), and online and local advertisements. Diagnosis of ASD was based on clinical evaluation and confirmed with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (Lord, Rutter, & Couteur, 1994) and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd Edition (ADOS-2) (Lord et al., 2012). Control participants were required to have a full-scale IQ (FSIQ) > 70 whereas ASD participants were examined on an individual basis to determine his/her ability to complete study procedures. Exclusionary criteria included any evidence of genetic/metabolic disorders, a history of traumatic head injury/asphyxia at birth, unstable medical conditions, or MR contraindication. Control participants were also required to have no history of learning disabilities or affective/psychiatric disorders, as assessed with parent-report questionnaires and the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1999) and have a minimal gestational age of 32 weeks and minimum birth weight of 3.3 pounds. The ASD and TD groups were group-matched for age, sex, handedness, as assessed with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971), and socioeconomic status (SES), which was computed based on the Hollingshead method (Hollingshead, 1975). Following screening, twin pair zygosity was confirmed from DNA extracted with cheek swabs. Nine short tandem repeat loci and the X/Y amelogenin were amplified and compared within twin pairs; concordance on all markers was considered MZ whereas discordance for at least one marker was considered DZ (Hallmayer et al., 2011). The methodology of the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from parents and assent from participants.

2.2 Cognitive and Behavioral Testing

Cognitive abilities were assessed with the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition (SB5), which can be administered to individuals aged 2 to 85 with or without reading/writing abilities (Roid, 2003). The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), a parent report questionnaire of ASD-related behaviors (Constantino & Gruber, 2007), and the Short Sensory Profile (SSP), a caregiver questionnaire that examines multi-modal sensory processing (Dunn, 1999), were also administered. Higher values on the SRS reflect more severe social deficits while lower values on the SSP indicate more severe sensory abnormalities.

2.3 MRI Acquisition and Processing

MRI was carried out at two scanning sites at the same institution, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (LPCH) and the Richard M. Lucas Center for Imaging, on identical GE 3T MR750 scanners (Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA) using a standard 8-channel head coil. Participants unable to remain motionless were administered a sedating agent (propofol) at LPCH under the supervision of an anesthesiologist at a rate of 200–300 mcg/kg/min to induce light procedural sedation. A double spin-echo sequence to obtain T2 and proton density weighted images in the axial plane was acquired with the following parameters: Auto TR min = 2500/max = 11000 msec, TE Min Full min = 12/max = 169 msec, Flip angle 111°, 3.0 mm thick, 0 mm gap, 1 NEX, FOV 22 cm, and a 320 × 256 matrix. A 2D phase-encoded point resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS-CSI) was then prescribed on the T2 weighted image to acquire water-suppressed 1H MRS data: TR 2300 msec, TE 35 msec, 5000 Hz spectral bandwidth, 2048 datapoints, 20 mm slice thickness, 24 cm FOV, 16 × 16 in plane matrix and 10 min acquisition.

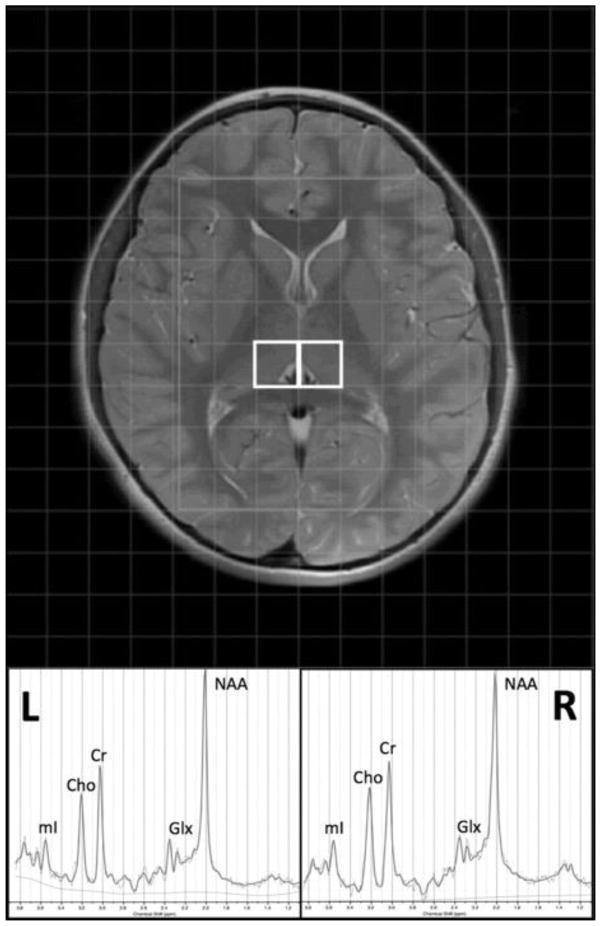

MRI processing was conducted utilizing SPM (Friston, 1994), LCModel (Provencher, 2001), and in-house Matlab scripts (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA). Anatomical T2-weighted images were segmented with SPM8 to form partial volume maps of grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The MRS grid was then co-registered to the anatomical images and partial volume maps utilizing in-house Matlab scripts. The anatomical volume corresponding to the midpoint of each MRS slab was used for registration of each voxel of interest (VOI). The grid was shifted within the acquisition plane to allow optimized localization based on anatomical structure. VOIs were centered on the right and left thalamus to include primarily thalamic GM (Figure 1) and had a nominal resolution of 1.5 × 1.5 × 2 cm. Additional VOIs centered on other deep brain structures relevant to the study of ASD, such as the head of the caudate/putamen, will be evaluated in future examinations of this multi-voxel dataset. Spectra were referenced to the standard PRESS basis set provided by LCModel and neurometabolites were quantified based on the ratio to creatine + phosphocreatine (tCr). The primary neurometabolite of interest was N-acetyl aspartate (NAA: a marker of neuronal integrity); however, choline-containing compounds including glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine (Cho: a marker of cellular membrane degradation/maturation), myoinositol (mI: a glial cell marker), and glutamate + glutamine (Glx: the primary excitatory neurotransmitter and its major metabolite) were also examined on an exploratory basis. Initial quality assessment included visual inspection for standard peaks (NAA, Cho & tCr) and residual macromolecule and lipid signals. Cramer-Rao lower bounds (≤20 %) were used as a conservative threshold for the inclusion of individual neurometabolite data from each participant.

Figure 1. Thalamic voxel localization and representative 1H MRS spectrum.

Voxels in the left (L) and (R) thalamus and an example spectrum from LCModel (Provencher, 2001) are displayed with the primary neurometabolite peaks, including N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), choline-containing compounds including glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine (Cho), creatine (Cr), myoinositol (mI), and glutamate + glutamine (Glx).

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Initial group comparisons were conducted with only a single twin from each pair; however, models that included all subjects were also evaluated to confirm that any group differences were not due to selection bias. Single twin comparisons included the individual from each ASD twin pair that exhibited the most severe symptoms (based on the ADOS-2) and a randomly-selected individual from each TD twin pair, selected with Research Randomizer software (Urbaniak & Plous, 2013). This approach allowed an initial focus on confirmed autism cases, which was the primary comparison of interest, while accounting for potential confounding covariation within twin pairs. Models with both co-twins from each pair were then evaluated and also included individuals from the ASD twin pairs that exhibited a broader autism phenotype (BAP: individuals with ASD-related symptomatology that did not meet ADI-R and ADOS criteria for autism). Twin pairs that were discordant for ASD (i.e., one co-twin met ADI-R and ADOS criteria for autism whereas the other co-twin exhibited no clinical indication of autism, including ADI-R and ADOS assessment) were examined separately.

Continuous demographic variables and symptom severity scores were compared between groups with independent samples t-tests and categorical demographic variables with χ2 (chi-squared). Neurometabolite ratios from the thalamus were examined with mixed effects regression models, separately for each metabolite, covarying for tissue composition (i.e., proportion of GM and WM within each VOI). Normality of neurometabolite ratios were examined with the Shapiro-Wilk test and log transformed before analysis when p ≤ 0.05. Within twin pairs discordant for ASD, neurometabolite ratios were examined with repeated measures ANCOVA, adjusted for tissue composition. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (i.e., p ≤ 0.025) was based on the number of regions of interest (L and R thalamus) for the primary analysis (i.e., NAA between ASD and TD for single twin comparisons). Intra-class correlations (ICC) of neurometabolite ratios, adjusted for tissue composition, sex, and SES, were examined in MZ and DZ twin pairs, excluding pairs discordant for ASD, and compared with Fisher’s r to z transformation. The ACE model for broad sense heritability (a2=additive genetics) and environmental influences (c2=shared family environment, e2=unique environment) was calculated using Falconer’s formula (Falconer, 1981), providing an estimate of the proportion of variation associated with each factor. Additionally, correlations between clinically-relevant neurometabolites and symptom severity scores were examined in an exploratory analysis, uncorrected for multiple comparisons. The primary associations that were evaluated (n=6) were between NAA in the left or right thalamus and the main symptom domains of ASD, including SCI (SRS: Social Communication Impairments), RRB (SRS: Autistic Mannerisms), and SPA (SSP: Total); however, correlations between total SRS scores and the subscales of the SSP with NAA ratios in the left or right thalamus (n=16) were also evaluated.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Participants

1H MRS scans were successfully acquired from 47 twin pairs with ASD (21 MZ and 26 DZ) and 33 control twin pairs (19 MZ and 14 DZ). The ASD and control groups did not differ in age, sex, handedness, ethnicity, or SES, p > 0.05 in all instances (Table 1). As expected, individuals with ASD exhibited significantly lower IQ and greater impairments on the SRS and SSP compared to TD controls, p < 0.001. Following QA, scans with good quality spectra were available from 77 individuals with ASD (36 MZ and 41 DZ) of which 36% received sedation. ASD participants receiving sedation exhibited greater symptom severity (SRS: M = 80.11, SD = 13.40) and lower IQ (SB5: M = 61.83, SD = 25.89) compared to the remaining ASD cohort (SRS: M = 67.08, SD = 15.82; SB5: M = 92.42, SD = 19.58), t(73) = −3.61, p = 0.001 and t(74) = 5.82, p < 0.001. Pregnancy information, comorbid diagnoses, and participant medications are outlined in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the ASD sample consisted of 29 complete pairs of twins with at least one twin with confirmed ASD and the other at least BAP (14 MZ and 15 DZ) and 11 complete pairs of twins with one twin with confirmed ASD and other twin exhibiting no significant autism-related symptoms, as assessed with the ADI-R and ADOS (Supplementary Table 2). Good quality spectra were available from 57 TD controls (34 MZ and 23 DZ), including 24 complete twin pairs (15 MZ and 9 DZ). There was no difference in the frequency of asymptomatic incidental brain findings between twins with ASD, un-affected co-twins, and TD controls, p = 0.40, as previously described (Monterrey et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics.

|

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ASD | TD | AS D vs TD | Add. Comps | |||||

| Twin Pairs | MZ (n=21) | DZ (n=26) | All (n=47) | M Z (n=19) | DZ (n=14) | All (n=33) | t or χ2 | p | |

| Age (years) | 10.76(2.79) | 10.77(2.52) | 10.77(2.61) | 10.21(2.49) | 9.21(2.75) | 9.79(2.61) | 1.65 | 0.10 | |

| Sex (male/female) | 15/6 | 22/4 | 37/10 | 14/5 | 9/5 | 23/10 | 0.84 | 0.36 | |

| Ethnicity (A/B/H/W/M O/U) | 1/0/1/14/5/0 | 2/1/3/15/3/2 | 3/1/4/29/8/2 | 1/0/1/14/3/0 | 2/0/0/12/0/0 | 3/0/1/26/3/0 | 4.94 | 0.42 | |

| SES | 56.41(8.38) | 50.57(10.36) | 53.05(9.89) | 54.95(7.26) | 58.07(8.72) | 56.27(7.93) | −1.51 | 0.14 | d |

|

| |||||||||

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||||

| Individuals | MZ (n=36) | DZ (n=41) | All (n=77) | MZ (n=34) | DZ (n=23) | All (n=57) | t | p | Add. Comps |

|

| |||||||||

| Handedness (right/left) | 31/5 | 35/6 | 66/11 | 31/3 | 21/2 | 52/5 | 0.95 | 0.33 | |

| Full Scale IQ | 84.28(26.34) | 78.34(26.66) | 81.15(26.50) | 110.47(10.28) | 115.43(12.45) | 112.47(11.36) | −8.36 | <0.001* | c,d |

| Short Sensory Profile | 144.03(23.27) | 140.88(27.37) | 142.25(25.53) | 174.47(11.83) | 176.33(19.89) | 175.24(15.50) | −8.20 | <0.001* | c,d |

| Social Responsiveness Scale | 73.58(14.24) | 70.10(17.79) | 71.77(16.17) | 46.03(5.57) | 42.77(3.87) | 44.75(5.19) | 12.04 | <0.001* | b,c,d |

| ADI-R Diagnostic Total | 42.03(11.63) | 36.54(18.90) | 39.10(16.06) | - | - | - | |||

| ADOS-2 Comparison Score | 7.19(1.97) | 7.15(2.35) | 7.17(2.16) | - | - | - | |||

The current samples are segregated by zygosity, monozygotic (M Z) and dizygotic (DZ), and comprised of twin pairs with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and typically -developing (TD) controls or all individuals with confirmed ASD versus all controls. Socioeconomic status (SES) was computed based on the Hollingshead method.(Hollingshead, 1975) Autism Diagnostic Inventory-Revised (ADI-R) Diagnostic Total is the sum of the Social Interaction, Communication, and Restricted/Repetitive Behavior subscales and comparison scores are from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd edition (ADOS-2). Group comparisons (ASD vs TD) were conducted with independent samples t tests (t) or chi-squared (χ2). A/B/H/W/M O/U=Asian/Black/Hispanic/White/multiple or other/unknown.

= ASD vs TD p ≤ 0.05

= M Z ASD vs. DZ ASD p ≤ 0.05

= MZ TD vs. DZ TD p ≤ 0.05

= MZ ASD vs. MZ TD p ≤ 0.05

= DZ ASD vs. DZ TD p ≤ 0.05

3.2 Thalamic Neurometabolites

Tissue composition did not differ between the ASD and TD groups for the proportion of GM (ASD M = 0.60, SD = 0.13; TD M = 0.60, SD = 0.13; t(78) = 0.04, p = 0.97 | ASD M = 0.55, SD = 0.15; TD M = 0.56, SD = 0.12; t(77) = −0.57, p = 0.57) or WM (ASD M = 0.21, SD = 0.14; TD M = 0.18, SD = 0.11; t(78) = 0.76, p = 0.45 | ASD M = 0.21, SD = 0.16; TD M = 0.16, SD = 0.09, t(77) = 1.55, p = 0.13), in the left and right thalamic nuclei, respectively, which indicated that thalamic GM was the primary tissue source that contributed to these neurometabolite signals. NAA was lower in the left thalamus in the most severely affected twins with ASD compared to TD controls, t(77) = −2.34, p = 0.02, which remained lower when controlling for NAA ratios in the contralateral thalamus, t(77) = −2.23, p = 0.03 and most importantly when comparing affected and unaffected co-twins, F(1,6) = 11.29, p = 0.02 (Table 2). These observations were generally supported when analyses included participants with less severe autism symptoms, p = 0.05, especially MZ twins, t(63) = −2.85, p = 0.01 (Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, examining males, t(58)= −2.11, p=0.04, and females, t(17) = −0.98, p = 0.34, separately indicated that a reduction in left thalamic NAA may be primarily found in males with ASD; however, the sample size of female participants (ASD: n = 10, TD: n = 10) likely limited our power to detect group differences. No statistically significant group differences were observed for the other metabolites in the right and left thalamus. Interestingly, Glx was lower in the left thalamus of affected compared to unaffected co-twins, F(1,4) = 18.28, p = 0.01, and Cho levels in the left (r = −0.18, p = 0.03) and right (r = −0.21, p = 0.01) thalamus were negatively associated with participant age (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2.

Thalamic neurometabolite levels in twins with and without ASD.

|

|

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD (n=47) | TD (n=33) | ASD vs TD | Affected Co-twin (n=11) | Unaffected Co-twin (n=11) | ASD vs Co-twin | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Left Thalamus | t | p | F | p | ||||

| NAA/tCr | 1.39(0.17) | 1.47(0.12) | −2.34 | 0.02** | 1.43(0.18) | 1.51(0.18) | 11.29 | 0.02** |

| mI/tCr | 0.62(0.17) | 0.62(0.15) | −0.11 | 0.92 | 0.68(0.13) | 0.66(0.15) | 0.85 | 0.42 |

| Cho/tCr | 0.29(0.06) | 0.30(0.04) | −1.23 | 0.22 | 0.28(0.05) | 0.31(0.04) | 0.004 | 0.95 |

| Glx/tCr | 1.82(0.64) | 1.86(0.32) | −0.90 | 0.37 | 1.88(0.54) | 2.09(0.39) | 18.28 | 0.01** |

|

| ||||||||

| Right Thalamus | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| NAA/tCr | 1.22(0.25) | 1.24(0.19) | −0.62 | 0.53 | 1.11(0.17) | 1.25(0.38) | 0.004 | 0.95 |

| mI/tCr | 0.92(0.34) | 0.95(0.17) | −1.11 | 0.27 | 0.94(0.15) | 0.82(0.18) | 0.48 | 0.54 |

| Cho/tCr | 0.34(0.09) | 0.34(0.05) | −0.24 | 0.81 | 0.32(0.05) | 0.33(0.04) | 0.12 | 0.75 |

| Glx/tCr | 2.09(0.52) | 2.16(0.43) | −0.81 | 0.42 | 2.14(0.36) | 2.06(0.41) | 0.49 | 0.51 |

The current samples are comprised of the most severely affected twin with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd edition, and a randomly selected typically-developing (TD) control twin (i.e., a single twin from each pair) or twin pairs that contain an affected (ASD) and unaffected co-twin. Neurometabolites include N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), choline-containing compounds including glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine (Cho), myoinositol (mI), and glutamate + glutamine (Glx) compared to internal creatine + phosphocreatine (tCr) levels. Group comparisons were based on mixed effects regression models (t) and repeated measures ANCOVA (F) within twin pairs discordant for ASD, adjusted for tissue composition. There was a single participant from which MRS data passed quality assessment for the left but not right thalamus.

= ASD vs TD p ≤ 0.05,

= ASD vs TD p ≤ 0.025 (adjusted for multiple comparisons across ROIs)

= adjusting for age p ≤ 0.05,

= adjusting for IQ p ≤ 0.05

3.3 Autism Symptomatology and Thalamic NAA

The relationships between thalamic NAA and clinical features of ASD were examined across all participants (regardless of diagnostic group) using a dimensional approach. Examining the most severely affected twin with ASD and a randomly-selected TD control twin from each pair, NAA in the left (r = −0.25, p = 0.03) and right (r = −0.24, p = 0.04) thalamic nuclei were associated with total SRS scores (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 1). NAA in the right thalamus was also associated with total SSP scores (r= 0.29, p = 0.01) and exhibited a trend for the left thalamus (r = 0.23, p = 0.06). Additionally, NAA in left thalamus was correlated with the SCI (r = −0.25, p = 0.03) and RRB (r = −0.24, p = 0.03) subscales of the SRS, and in the right thalamus was associated with SCI (r =−0.24, p = 0.04) and exhibited a trend with RRB (r = −0.21, p = 0.06). The subscales of the SSP had several significant associations with thalamic NAA, tactile processing being the most pronounced (left thalamus: r = 0.288, p = 0.01; right thalamus: r = 0.285, p = 0.01). These associations were largely unchanged when examining all participants, including individuals with less severe autism-related symptomatology and unaffected co-twins (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 3.

Correlations between NAA/tCr ratios and symptom severity in twins with and without ASD.

| Left Thalamus (n=80) | Right Thalamus (n=79) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Social Responsiveness Scale | r | CI | p | r | CI | p |

| SCI | −0.25 | [−0.45, −0.03] | 0.03*,+ | −0.24 | [−0.44, −0.02] | 0.04*,+,# |

| Autistic Mannerisms | −0.24 | [−0.44, −0.02] | 0.03*,+ | −0.21 | [−0.42, 0.01] | 0.06 |

| Total | −0.25 | [−0.45, −0.03] | 0.03*,+ | −0.24 | [−0.44, −0.02] | 0.04*,+ |

|

| ||||||

| Short Sensory Profile | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Total | 0.23 | [0.01, 0.43] | 0.06 | 0.29 | [0.07, 0.49] | 0.01*,+,# |

The current sample is comprised of the most severely affected twin with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd edition, and a randomly-selected typically-developing (TD) control twin (i.e., a single twin from each pair). Correlations between N-acetyl aspartate/creatine + phosphocreatine (NAA/tCr) and symptom severity on the Social Responsiveness Scale (Social Communication Impairments (SCI) and Autistic Mannerisms subscales) and the Short Sensory Profile are based on Pearson’s r and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided. Within the current sample, there was a single participant from which MRS data passed quality assessment for the left but not right thalamus.

= r is statistically different from 0 at p ≤ 0.05

= adjusting for age p ≤ 0.05,

= adjusting for IQ p ≤ 0.05

3.4 Thalamic Neurometabolites in Twin Pairs

ICCs of average neurometabolite ratios across the left and right thalamic nuclei were examined within all MZ and DZ twin pairs regardless of diagnosis, excluding discordant twin pairs (Table 4). ICCs were significant for all neurometabolites in both MZ and DZ twin pairs, p < 0.05 in all instances, except for mI in DZ pairs, p = 0.18. Comparing MZ and DZ twin pairs, ICCs were higher in MZ twin pairs for all neurometabolites, p < 0.05 in all instances, except for Cho, p = 0.73. As such, NAA, mI, and Glx exhibited general additive genetic effects (a2 > c2 and e2), whereas Cho did not (c2 and e2 > a2). mI in the thalamus may have also exhibited genetic dominance (rMZ > 4*rDZ); however, the non-significant association within DZ twin pairs likely contributed to this observation.

Table 4.

Intra-class correlations of thalamic neurometabolite levels in twin pairs.

|

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZ Twin Pairs (n=29) | DZ Twin Pairs (n=24) | MZ vs DZ | ACE | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| ICC | CI | p | ICC | CI | p | z | p | a2 | c2 | e2 | |

| NAA/tCr | 0.88 | [0.81, 0.93] | <0.001* | 0.50 | [0.25, 0.68] | <0.001* | 4.06 | <0.001* | 0.77 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| mI/tCr | 0.79 | [0.66, 0.87] | <0.001* | 0.14 | [−0.16, 0.43] | 0.18 | 4.13 | <0.001* | 1.29 | −0.50 | 0.21 |

| Cho/tCr | 0.85 | [0.77, 0.91] | <0.001* | 0.83 | [0.72, 0.90] | <0.001* | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.15 |

| Glx/tCr | 0.79 | [0.67, 0.87] | <0.001* | 0.46 | [0.19, 0.67] | 0.001* | 2.74 | 0.01* | 0.67 | 0.13 | 0.21 |

The current sample is comprised of all twin pairs concordant for autism spectrum disorder and all typically-developing control twin pairs. Neurometabolites include N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), choline-containing compounds including glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine (Cho), myoinositol (mI), and glutamate + glutamine (Glx) compared to internal creatine + phosphocreatine (tCr) levels. Intra-class correlations (ICC) were based on average neurometabolite levels between the right and left thalamic nuclei adjusted from linear regression for diagnostic group, sex, tissue composition in the regions of interest, and socioeconomic status (and age for Glx). 95% confidence intervals (CI) are included. ICCs for monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs were transformed with Fisher’s r to z and compared between groups. ACE estimates were based on Falconer’s formula where a2=2(rMZ-rDZ), c2=2rDZ-rMZ, and e2=1-(a2+c2).

= ICC is statistically different from 0 at p ≤ 0.05 or MZ vs DZ p ≤ 0.05.

Examining ASD and TD twin pairs separately indicated some potentially relevant differences (Supplementary Table 6). In MZ twin pairs concordant for ASD, ICC estimates were significant for NAA and Glx (p < 0.001); however, mI and Cho, as well as all neurometabolites in DZ ASD twin pairs, were not (p > 0.05 in all instances). Within TD twin pairs, ICC estimates for all neurometabolites were significant in MZ twins (p < 0.001 in all instances); but only Cho was significant in DZ twins (p < 0.001), with the remaining neurometabolites exhibiting a trend (p > 0.05). Comparing MZ and DZ twin pairs concordant for ASD, only NAA exhibited a statistically significant difference (z= 3.02, p = 0.003); whereas in control twins, mI (z= 4.09, p < 0.001) and Cho (z= 2.78, p = 0.01) both differed. Comparing ASD and TD twin pairs, mI (z= −5.31, p < 0.001) and Cho (z= −5.60, p < 0.001) differed between MZ twin pairs, but only Cho (z= −3.10, p = 0.002) was altered in DZ pairs. These alterations were most likely not related to subgroup differences in confounding demographic influences because the groups were relatively well-matched; however, the TD DZ group exhibited higher SES compared to the ASD DZ group, t(22) = −2.18, p = 0.04 (Supplementary Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

In the first a priori investigation of this multi-voxel 1H MRS data, NAA/tCr in the thalamus was reduced in twins with ASD compared to TD controls, and this finding was confirmed in a more closely matched sub-sample of affected and unaffected co-twins, which provides additional controls for environmental and genetic influences. NAA ratios were also correlated with the core symptom domains of ASD, including SCI, RRB, and SPA, such that reduced neuronal integrity was associated with greater symptom severity. Furthermore, Glx/tCr was lower in affected versus unaffected co-twins. Thus, reduced neuronal integrity in the thalamus and altered glutamatergic metabolism may affect thalamic processing in individuals with ASD. Based on comparisons between MZ and DZ twin pairs, thalamic NAA and Glx were found to be primarily genetically-mediated, indicating that genetic susceptibility likely influences thalamic abnormalities in ASD. Overall, it appears that thalamic perturbations may represent a neurobiological abnormality in ASD that is shared across the core symptom domains and is interrelated with genetic-susceptibility towards disorder outcomes (Frazier et al., 2014).

Decreased NAA has been reported in some (Friedman et al., 2003; Hardan et al., 2008; Perich-Alsina et al., 2002) but not all (Bernardi et al., 2011; Doyle-Thomas et al., 2014; Levitt et al., 2003) 1H MRS investigations of the thalamus in ASD. Discrepancies between these studies might be related to differences in the study populations and regions of interest. Reduced thalamic NAA was previously reported in children and adolescents with ASD (Friedman et al., 2003; Hardan et al., 2008; Perich-Alsina et al., 2002) but not adults (Bernardi et al., 2011), which could be related to compensatory mechanisms or the possible “normalization” observed in some neurobiological measures at specific developmental periods (Barnea-Goraly et al., 2014; Courchesne, Campbell, & Solso, 2011; Frazier, Keshavan, Minshew, & Hardan, 2012). The only negative studies that examined children with ASD (Doyle-Thomas et al., 2014; Levitt et al., 2003) utilized acquisition slabs that were approximately one-half (10–12 mm) the thickness of the majority of the positive studies (20 mm), which would have limited signal acquisition to a smaller portion of the thalamus. Additionally, a meta-analysis across 1H MRS studies examining multiple brain regions in children with ASD reported a highly significant reduction in thalamic NAA, p = 0.0002 (Aoki, Kasai, & Yamasue, 2012), consistent with the current investigation. Our observation of lower NAA in the left but not the right thalamus is also consistent with earlier reports of selective left hemispheric impairments in ASD (Chiron et al., 1995; Dawson, Warrenburg, & Fuller, 1982; Hazlett, Poe, Gerig, Smith, & Piven, 2006), especially regarding typically left-lateralized cognitive domains such as language (Escalante-Mead, Minshew, & Sweeney, 2003; Eyler, Pierce, & Courchesne, 2012; Just, Cherkassky, Keller, & Minshew, 2004). These previous studies suggest that the lateralized abnormalities found in the current sample are likely related to a more generalized alteration in cerebral lateralization during development. Most importantly, the aforementioned 1H MRS investigations of the thalamus in children with ASD have consistently reported left hemispheric reductions of thalamic NAA (Friedman et al., 2003; Hardan et al., 2008; Perich-Alsina et al., 2002).

Thalamic alterations have also been reported in ASD in several other studies in which there were indications of histological (Ray et al., 2005), morphometric (Hardan et al., 2006; Tamura et al., 2010; Tsatsanis et al., 2003), and functional (Haznedar et al., 2006; Mizuno et al., 2006; Nair et al., 2013) abnormalities in this structure. Although limited, neuronal alterations have also been reported with evidence of a loss of α7 and β2 neurons in the nucleus reuniens of the thalamus in individuals with ASD (Ray et al., 2005). Volumetric abnormalities have also been observed with reports of a reduction in thalamic size (Tamura et al., 2010) and an altered relationship between total brain and thalamic volumes (Hardan et al., 2006; Tsatsanis et al., 2003). Functional neuroimaging investigations have also reported alterations in thalamic processing in ASD, with reports of lower glucose metabolism (Haznedar et al., 2006) and abnormal connectivity between the thalamus and several other brain regions (Mizuno et al., 2006; Nair et al., 2013), suggesting that reduced neuronal integrity in this structure may affect network-level processing in multiple network streams. This is consistent with our observations of associations between NAA and multiple clinical features of the disorder, which is not surprising considering the thalamus is involved in filtering almost all incoming information to the brain. These observations are also consistent with more recent studies (Frazier et al., 2014; Lichtenstein, Carlström, Råstam, Gillberg, & Anckarsäter, 2010) that suggest a stronger clinical and genetic relationship between ASD symptom domains (SCI and RRB) than previously reported (Ronald et al., 2006a; Ronald et al., 2005). Thus, our findings suggest that neuronal integrity of the thalamus may be interrelated with symptom severity across the core domains of ASD, at least to some extent, and provides support for theories of circuit level processing abnormalities in ASD by further implicating a central processing hub in the brain.

MZ and DZ twin pairs were assessed in this neuroimaging investigation, which, to our knowledge, is the first examination of neurometabolites in twins with and without ASD. Our preliminary findings suggest that neurometabolites in the thalamus are primarily genetically-mediated in children and adolescents, which is consistent with a previous investigation of the posterior cingulate cortex in TD adults (Batouli et al., 2012). In the current investigation, NAA, mI, and Glx exhibited significant additive genetic effects. These findings, particularly NAA (a2=0.77), are consistent with a structural neuroimaging study in TD twins which reported considerable genetic influence (a2=0.72) on the size of the thalamus (Schmitt et al., 2007). In contrast, Cho appeared to be primarily influenced by environmental factors, which is also consistent with previous reports (Batouli et al., 2012). Interestingly, Cho is typically elevated in instances of neuroinflammation and in the presence of neoplasms, which may occur following environmental exposure (Reuter, Gupta, Chaturvedi, & Aggarwal, 2010). Finally, there appeared to be some potentially relevant differences in genetic influences on neurometabolites in ASD. Genetic factors may have exerted a larger impact on NAA in twins with ASD compared to TD controls, which could be interrelated with the reported reduction in NAA. In contrast, mI, a glial cell marker, may be less genetically-mediated in ASD; however, these observations are limited by the small sample size.

4.1 Limitations

In the current exploratory investigation, only basic corrections for multiple comparisons were applied and the study was not powered to apply more advanced modeling techniques to assess heritability. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that abnormal NAA ratios in the thalamus, and to some extent Glx, are associated with ASD symptom severity and that neurometabolites in the thalamus may be primarily genetically-mediated. Although the correlations between NAA and SCI, RRB, and SPA were generally low magnitude, r = |0.20 to 0.30| and accounted for only a small proportion of total variance, correlations within this range may indicate more meaningful relationships than previously thought (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016). Furthermore, it is the similarity across these symptom domains that supports our interpretation that thalamic abnormalities are likely not domain-specific in ASD. Unfortunately, the current samples were not large enough to comprehensively assess between-group differences in genetic and environmental influences, but our preliminary data suggest potential ASD-related differences in genetic factors that affect neurometabolites, which will need to be evaluated in larger samples of twins with and without ASD. This will be particularly important for TD DZ twin pairs and female twin pairs with ASD because of the small subgroup sample size and potential confounding demographic differences, such as SES. Additionally, our sample included participants at different developmental periods with variable levels of cognitive functioning. The effects of these factors were assessed throughout the analyses, and overall age did not significantly alter the reported results. IQ accounted for some ASD-related differences; however, this is to be expected when examining individuals in which IQ often covaries with symptom severity.

As with any investigation based on multi-voxel 1H MRS, spectral quality may have been reduced with additional contamination from adjacent voxels compared to single voxel acquisition. There are also inherent limitations when utilizing a neurometabolite reference, such as tCr; however, tCr is the most commonly utilized internal reference because concentrations are relatively consistent across individuals due to the role of the tCr cycle in energy consumption and ATP metabolism. Although, there have been some reports of altered tCr in ASD (see Aoki et al. (2012) for a review), these differences did not survive multiple comparisons and were several orders of magnitude smaller compared to NAA (Aoki et al., 2012). Additionally, differences across imaging sites and sedation with propofol (Kawaguchi et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2009) were also potential confounding factors. To assess potential site differences, we scanned three participants on both scanners and found no significant alterations in NAA ratios across sites. To assess potential effects from propofol, we also compared NAA between twins with ASD who were not sedated and TD controls, but found no statistically significant differences between groups, p > 0.05. However, this was likely due to the aforementioned relationship between propofol administration and autism severity in the current sample. When we focused on individuals that exhibited symptom severity above the 75th percentile, NAA ratios were indeed reduced in individuals with ASD that did not undergo sedation, p = 0.03. Additionally, the previously-reported differences following propofol administration were only found with significantly higher doses and longer rates of administration (Kawaguchi et al., 2010) than the current investigation employed or when the participant was in a deeper unconscious state (Zhang et al., 2009). Importantly, similar neurometabolic alterations, including reduced NAA in the thalamus (Hardan et al., 2008), have been previously reported in ASD without the use of sedation.

Future studies should apply longitudinal assessment of young children with ASD, preferably without the use of sedation, to evaluate the developmental trajectory of neurometabolic profiles in ASD as well as assess larger groups of female twins with ASD. These steps will be important for determining the gender-specificity of these alterations and identifying whether thalamic abnormalities are a pertinent developmental alteration or simply an outcome of perturbations in other regions of the brain. Additionally, it is unclear whether our observations are specific to ASD. For example, reduced NAA in the thalamus has also been reported in schizophrenia (Auer et al., 2001). Future studies will need to compare these thalamic abnormalities to patients with other neuropsychiatric and neurogenetic disorders.

4.2 Conclusion

NAA in the thalamus was reduced in twins with ASD compared to TD controls and associated to a similar extent with SCI, RRB, and SPA symptom severity. Neurometabolite ratios in the thalamus, including NAA, appeared to be primarily genetically-mediated, and although preliminary, we provide evidence that genetic factors may be interrelated with reduced NAA in ASD. Thus, genetic-susceptibility for ASD may alter neuronal integrity of the thalamus during development and affect cognitive and behavioral processing by modifying thalamic filtering. However, multi-modal investigations of younger twins or neurogenetic subgroups will be necessary to elucidate these pathways.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Twins with ASD had thalamic abnormalities relative to controls/unaffected co-twins.

Thalamic neurometabolite levels were correlated with multiple symptom domains.

Comparing twin pairs, neurometabolite levels were primarily genetically-mediated.

Thalamic abnormalities in ASD are influenced by genetics but not domain-specific.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH083972 to A.Y.H.) and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (P41EB015891 to D.M.S.) of the National Institutes of Health. J.P.H was supported by the Bass Society Pediatric Fellowship program. The efforts of all participants and their families are greatly appreciated. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

- TD

typically-developing

- BAP

broader autism phenotype

- SCI

social communication impairments

- RRB

restricted and repetitive behaviors

- SPA

sensory processing abnormalities

- SSP

Short Sensory Profile

- MZ

monozygotic

- DZ

dizygotic

- MRS

1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- VOI

voxel of interest

- NAA

N-acetyl aspartate

- tCr

creatine + phosphocreatine

- Glx

glutamate + glutamine

- mI

myoinositol

- Cho

choline-containing compounds

- a2

additive genetics

- c2

shared or common environment

- e2

unique environment

Footnotes

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The methodology of the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from parents and assent from participants. The privacy rights of all human subjects have been observed. The authors also have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 2. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999. The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments; pp. 429–466. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends in neurosciences. 2008;31(3):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y, Kasai K, Yamasue H. Age-related change in brain metabolite abnormalities in autism: a meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e69. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V. Arlington, VA: 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer DP, Wilke M, Grabner A, Heidenreich JO, Bronisch T, Wetter TC. Reduced NAA in the thalamus and altered membrane and glial metabolism in schizophrenic patients detected by 1 H-MRS and tissue segmentation. Schizophrenia research. 2001;52(1):87–99. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25(01):63–77. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea-Goraly N, Frazier TW, Piacenza L, Minshew NJ, Keshavan MS, Reiss AL, Hardan AY. A preliminary longitudinal volumetric MRI study of amygdala and hippocampal volumes in autism. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2014;48:124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batouli SAH, Sachdev PS, Wen W, Wright MJ, Suo C, Ames D, Trollor JN. The heritability of brain metabolites on proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in older individuals. NeuroImage. 2012;62(1):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.043. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi S, Anagnostou E, Shen J, Kolevzon A, Buxbaum JD, Hollander E, … Fan J. In vivo 1 H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the attentional networks in autism. Brain research. 2011;1380:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among children aged 8 years: autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR CDC Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon KA, Kim YS, Oh SH, Park SY, Yoon HW, Herrington J, … Kim Y-B. Involvement of the anterior thalamic radiation in boys with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a Diffusion Tensor Imaging study. Brain research. 2011;1417:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiron C, Leboyer M, Leon F, Jambaque L, Nuttin C, Syrota A. SPECT of the brain in childhood autism: evidence for a lack of normal hemispheric asymmetry. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1995;37(10):849–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1995.tb11938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social responsiveness scale (SRS) Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Todd RD. Autistic traits in the general population: a twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):524–530. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, Campbell K, Solso S. Brain growth across the life span in autism: age-specific changes in anatomical pathology. Brain Res. 2011;1380:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Warrenburg S, Fuller P. Cerebral lateralization in individuals diagnosed as autistic in early childhood. Brain and Language. 1982;15(2):353–368. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(82)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle-Thomas KAR, Card D, Soorya LV, Ting Wang A, Fan J, Anagnostou E. Metabolic mapping of deep brain structures and associations with symptomatology in autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.10.003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. Short sensory profile. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante-Mead PR, Minshew NJ, Sweeney JA. Abnormal brain lateralization in high-functioning autism. Journal of autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33(5):539–543. doi: 10.1023/a:1025887713788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler LT, Pierce K, Courchesne E. A failure of left temporal cortex to specialize for language is an early emerging and fundamental property of autism. Brain. 2012;135(3):949–960. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS. Introduction to quantitative genetics. 2. London: Longman; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein SE, Rutter M. Infantile Autism: A Genetic Study of 21 Twin Pairs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;18(4):297–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1977.tb00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Keshavan MS, Minshew NJ, Hardan AY. A two-year longitudinal MRI study of the corpus callosum in autism. Journal of autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(11):2312–2322. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1478-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Thompson L, Youngstrom EA, Law P, Hardan AY, Eng C, Morris N. A Twin Study of Heritable and Shared Environmental Contributions to Autism. Journal of autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(8):2013–2025. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SD, Shaw DW, Artru AA, Richards TL, Gardner J, Dawson G, … Dager SR. Regional brain chemical alterations in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Neurology. 2003;60:100–107. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ. Functional and effective connectivity in neuroimaging: a synthesis. Human Brain Mapping. 1994;2(1–2):56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gignac GE, Szodorai ET. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;102:74–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, … Risch N. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. JAMA Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan AY, Girgis RR, Adams J, Gilbert AR, Keshavan MS, Minshew NJ. Abnormal brain size effect on the thalamus in autism. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2006;147(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan AY, Minshew NJ, Melhem NM, Srihari S, Jo B, Bansal R, … Stanley JA. An MRI and proton spectroscopy study of the thalamus in children with autism. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2008;163(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett HC, Poe MD, Gerig G, Smith RG, Piven J. Cortical gray and white brain tissue volume in adolescents and adults with autism. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar MM, Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA, LiCalzi EM, Cartwright C, Hollander E. Volumetric analysis and three-dimensional glucose metabolic mapping of the striatum and thalamus in patients with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1252–1263. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status [Unpublished manuscript] Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Minshew NJ. Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain. 2004;127(8):1811–1821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Burnette CP, Eliez S, Strunge LA, Kaplan D, Landa R, … Pearlson GD. Neuroanatomic variation in monozygotic twin pairs discordant for the narrow phenotype for autism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):539–546. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Ikuta I, Burnette CP. Gyrification patterns in monozygotic twin pairs varying in discordance for autism. Autism Research. 2009;2(5):267–278. doi: 10.1002/aur.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi H, Hirakawa K, Miyauchi K, Koike K, Ohno Y, Sakamoto A. Pattern recognition analysis of proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of brain tissue extracts from rats anesthetized with propofol or isoflurane. PloS one. 2010;5(6):e11172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintwall L, Holm A, Eriksson M, Carlsson LH, Olsson MB, Hedvall Å, … Fernell E. Sensory abnormalities in autism: a brief report. Research in developmental disabilities. 2011;32(2):795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leekam SR, Nieto C, Libby SJ, Wing L, Gould J. Describing the Sensory Abnormalities of Children and Adults with Autism. Journal of autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(5):894–910. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt JG, O’Neill J, Blanton RE, Smalley S, Fadale D, McCracken JT, … Alger JR. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of the brain in childhood autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1355–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Carlström E, Råstam M, Gillberg C, Anckarsäter H. The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1357–1363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24(5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/bf02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–2nd edition (ADOS-2) Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Corporation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mandy WP, Skuse DH. Research Review: What is the association between the social–communication element of autism and repetitive interests, behaviours and activities? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(8):795–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevel K, Fransson P, Bölte S. Multimodal brain imaging in autism spectrum disorder and the promise of twin research. Autism. 2015;19(5):527–541. doi: 10.1177/1362361314535510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SR, Reiss AL, Tatusko DH, Ikuta I, Kazmerski DB, Botti J-AC, … Kates WR. Neuroanatomic alterations and social and communication deficits in monozygotic twins discordant for autism disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno A, Villalobos ME, Davies MM, Dahl BC, Müller RA. Partially enhanced thalamocortical functional connectivity in autism. Brain research. 2006;1104(1):160–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterrey JC, Philips J, Cleveland S, Tanaka S, Barnes P, Hallmayer JF, … Hardan AY. Incidental brain MRI findings in an autism twin study. Autism Research. 2017;10(1):113–120. doi: 10.1002/aur.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair A, Treiber JM, Shukla DK, Shih P, Müller RA. Impaired thalamocortical connectivity in autism spectrum disorder: a study of functional and anatomical connectivity. Brain. 2013;136(6):1942–1955. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perich-Alsina J, Aduna dPM, Valls A, Muñoz-Yunta J. Thalamic spectroscopy using magnetic resonance in autism. Revista de neurologia. 2002;34:S68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(4):260–264. doi: 10.1002/nbm.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray MA, Graham AJ, Lee M, Perry RH, Court JA, Perry EK. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in autism: an immunohistochemical investigation in the thalamus. Neurobiology of Disease. 2005;19(3):366–377. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2010;49(11):1603–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH. Stanford-Binet intelligence scales. Riverside Publishing; Itasca, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, HappÉ F, Bolton P, Butcher LM, Price TS, Wheelwright S, … Plomin R. Genetic Heterogeneity Between the Three Components of the Autism Spectrum: A Twin Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006a;45(6):691–699. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215325.13058.9d. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000215325.13058.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Happé F, Plomin R. The genetic relationship between individual differences in social and nonsocial behaviours characteristic of autism. Developmental Science. 2005;8(5):444–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, HappÉ F, Price TS, Baron-Cohen S, Plomin R. Phenotypic and Genetic Overlap Between Autistic Traits at the Extremes of the General Population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006b;45(10):1206–1214. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000230165.54117.41. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000230165.54117.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt JE, Wallace GL, Rosenthal MA, Molloy EA, Ordaz S, Lenroot R, … Giedd JN. A multivariate analysis of neuroanatomic relationships in a genetically informative pediatric sample. NeuroImage. 2007;35(1):70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.232. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffenburg S, Gillberg C, Kellgren L, Andersson L, Gillberg IC, Jakobsson G, Bohman M. A Twin Study of Autism in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;30(3):405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura R, Kitamura H, Endo T, Hasegawa N, Someya T. Reduced thalamic volume observed across different subgroups of autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2010;184(3):186–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsanis KD, Rourke BP, Klin A, Volkmar FR, Cicchetti D, Schultz RT. Reduced thalamic volume in high-functioning individuals with autism. Biological psychiatry. 2003;53(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak GC, Plous S. Research Randomizer (Version 4.0) 2013 http://www.randomizer.org/

- Zhang H, Wang W, Gao W, Ge Y, Zhang J, Wu S, Xu L. Effect of propofol on the levels of neurotransmitters in normal human brain: a magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuroscience letters. 2009;467(3):247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.