Abstract

The prevalence of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) spores was assessed in 48 observations of infected inpatients. Participants were randomized to hand hygiene with either alcohol based hand rub or soap and water. C. difficile was recovered in 14.6% of pre-hand hygiene observations. It was still present on five of these seven participants after hand hygiene (3/3 alcohol based hand rub; 2/4 soap and water).

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, hand hygiene, infection prevention, healthcare associated infection

Background

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) accounts for 12.1% of healthcare-associated infections, resulting in nearly 500,000 cases and 15,000 deaths in the United States each year(1,2). Patient hand hygiene is underutilized in infection control campaigns, although patients themselves play a key role in the transmission of infection(3). Patients are less likely to perform proper hand hygiene in a hospital than at home, because of limited mobility and the institution's perceived cleanliness (4).

Alcohol based hand rubs (ABHR) are ineffective against C. difficile spores and soap and water is a key component of hand hygiene interventions during C. difficile infection (CDI) outbreaks(5). However, there is little literature addressing hand contamination and the role of ABHR in the disinfection of the hands of CDI patients. We conducted a study to assess the baseline prevalence of C. difficile on CDI patients' hands and compare the effectiveness of ABHR versus soap and water at eliminating C. difficile when present.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted from October 2015 to February 2016 at a 505 bed academic hospital where multiple CDI-targeted prevention efforts were in place. These included enhanced personal protective equipment, isolation for the duration of hospitalization, and institution-wide surveillance. The study was considered quality improvement and was exempt from IRB review.

Inpatient children and adults diagnosed with active CDI were recruited into the study by convenience sampling. CDI status was defined by a positive C. difficile PCR test in patients with symptomatic diarrhea. Because patients started antibiotic treatment upon CDI diagnosis and often enrolled several days after diagnosis, participants were not required to have active diarrhea at enrollment. Patients younger than eight and those in the psychiatry unit were excluded. All participants provided consent before participating, with the exception of cognitively impaired patients, for whom verbal consent was provided by a family member.

All participants were randomized to ABHR or soap and water hand hygiene by an online randomization tool(6). Two rounds of microbial testing were conducted, with hand hygiene taking place between tests. In ABHR, a 62% ethanol rub was applied to participants' hands for 30 seconds. For soap and water, mobile participants washed their hands up to the wrist in the sink for 30 seconds, using ∼2 ml of chlorhexidine antimicrobial soap. Cognitively impaired and limited mobility participants were assisted by a researcher using a bedside basin and pitcher of water. All participants' hands were dried with clean paper towels. A second microbial testing procedure was conducted immediately after the participant's hands dried. To prevent cross-contamination and promote patient safety, the research assistant performed hand hygiene with ABHR and donned a gown and gloves before entering all participant rooms.

The presence of C. difficile spores was measured using a modified version of the glove juice protocol (7). Fifty mL of sampling solution (1× PBS, 7g/L Lecithin, 6g/L sodiumthiosulfate) was utilized. Following sample collection, one aliquot of sampling solution was incorporated in C. difficile brucella broth and another platted on C. difficile brucella agar (CDBA). Both were incubated anaerobically for 48-hours at 35°C. Broth that turned from pink to yellow was streaked for isolation on a CDBA plate. Gram stain and catalase tests were run for subsequent isolates grown on CDBA, followed by standard PCR on all presumptively positive isolates for species confirmation.

Results

Forty-four unique patients participated in the study for a total of 48 observations (Table 1). The four patients who participated twice were identified during separate hospital admissions. Pre-hand hygiene cultures recovered C. difficile in seven observations (14.6%). Among these participants, C. difficile was subsequently recovered after hand hygiene on all three performing ABHR (100%) and two washing with soap and water (50%, p = 0.182). Although not statistically significant, the five participants on which C. difficile was recovered were more likely than those who cleared C. difficile to have limited mobility (80% versus 20%) and be treated with vancomycin (80% versus 0%). There was no notable difference between these groups regarding altered mental status.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of observations (n=48).

| Characteristic | All observations (n = 48) | ABHR (n = 24) | Soap and Water (n = 24) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 16 (33.3) | 7 (29.2) | 9 (37.5) | 0.76 |

| Mean age, years (IQR) | 56.7 (49.5, 68.0) | 58.4 (53.5, 68.3) | 54.9 (48.0, 66.5) | 0.45 |

| Mean BMI (IQR) | 26.9 (21.1, 29.6) | 26.4 (20.3, 28.5) | 27.4 (22.6, 34.0) | 0.69 |

| Altered Mental Status* | 17 (36.2) | 10 (41.7) | 7 (30.4) | 0.62 |

| Limited Mobility* | 25 (53.2) | 15 (62.5) | 10 (43.5) | 0.31 |

| Primary C. difficile antibiotic treatment at time of enrollment | 0.69 | |||

| Vancomycin | 39 (84.8) | 21 (87.5) | 18 (81.8) | |

| Metronidazole | 7 (15.2) | 3 (12.5) | 4 (18.1) | |

| Mean time between laboratory confirmed C. difficile infection and study enrollment, days (IQR) | 5.5 (2.0, 7.0) | 6.1 (2.0, 7.5) | 4.8 (2.0, 7.0) | 0.41 |

Note: Data are number (%) of observations, unless otherwise indicated. Four participants were tested on two distinct admissions, totaling eight observations. C. difficile, Clostridium difficile; IQR, interquartile range

Ascertained from patient chart review

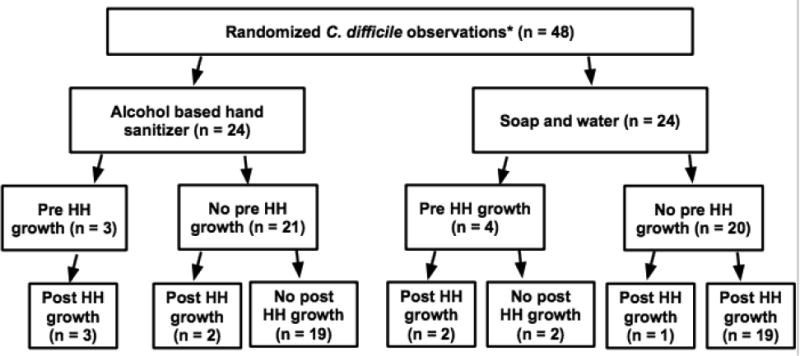

C. difficile was also recovered after hand hygiene on the hands of three participants previously negative for C. difficile hand flora at baseline (2 of 21 ABHR, 9.5%, 1 of 20 soap and water, 5.0%; p=0.587; Figure 1). One of the three participants had limited mobility, one had both limited mobility and altered mental status, and the third had neither.

Figure 1.

C. difficile growth based on the hand hygiene method. *Four participants were tested on two distinct admissions, totaling eight observations; HH: hand hygiene

All four participants providing two observations were randomized once to ABHR and once to soap and water (eight observations total). In seven of these observations, participants were negative for C. difficile spores pre- and post-hand hygiene. In the eighth, the participant was positive for C. difficile both before and after cleaning with soap and water.

Discussion

In our study of 48 CDI observations, 14.6% had C. difficile spores on the hand prior to hand hygiene. This result is half the prevalence reported in a prior study assessing hand hygiene effectiveness in C. difficile patients (8). This previous study found that 32.1% of CDI patients and 37.5% of asymptomatic carriers had C. difficile on the hand at baseline. Possible reasons for these disparate results include variation in the degree and severity of CDI. Time on effective CDI treatment and type of treatment may also impact shedding of CDI (9,10). Future studies are necessary to evaluate the reasons for variation in recovery of CDI from the hands of CDI patients.

Given the unanticipated low rate of C. difficile recovery at baseline, our assessment of the comparative efficacy of soap and water and ABHR is limited by small sample size. It is important to note that subjects' typical hand hygiene, even with soap and water, did not always remove C. difficile. With numerous known impediments to proper patient hand washing in the hospital setting, including invasive medical devices, immobility, and limited access to sinks, portable hand hygiene products that are effective against spore-forming organisms like C. difficile are urgently needed.

Conclusions

This study highlights the need for future work to rigorously assess effective hand hygiene methods for C. difficile.

Highlights.

C. difficile may remain on a high proportion of patient hands after soap and water.

New C. difficile contamination can occur immediately after patient hand hygiene.

Prevalence of C. difficile on patient hands may be lower than previously predicted.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant number R03HS023791 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AB was supported under NIH awards UL1TR000427 and TL1TR000429, administered by the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. Multistate Point-Prevalence Survey of Health Care–Associated Infections. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 27;370(13):1198–208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile Infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372(9):825–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landers T, Abusalem S, Coty MB, Bingham J. Patient-centered hand hygiene: The next step in infection prevention. Am J Infect Control. 2012 May;40(4, Supplement):S11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker A, Sethi A, Shulkin E, Caniza R, Zerbel S, Safdar N. Patient Hand Hygiene at Home Predicts Their Hand Hygiene Practices in the Hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol Off J Soc Hosp Epidemiol Am. 2014 May;35(5):585–8. doi: 10.1086/675826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubberke ER, Carling P, Carrico R, Donskey CJ, Loo VG, McDonald LC, et al. Strategies to Prevent Clostridium difficile Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infect Control Amp Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Sep;35(S2):S48–65. doi: 10.1017/s0899823x00193857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urbaniak GC, Plous S. Research Randomizer (Version 4.0) 2013 [Computer software]. Retrieved on June 22, 2013, from http://www.randomizer.org/

- 7.Michaud RN, McGrath MB, Goss WA. Improved Experimental Model for Measuring Skin Degerming Activity on the Human Hand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972 Jul;2(1):8–15. doi: 10.1128/aac.2.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kundrapu S, Sunkesula V, Jury I, Deshpande A, Donskey CJ. A randomized trial of soap and water hand wash versus alcohol hand rub for removal of Clostridium difficile spores from hands of patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Feb;35(2):204–6. doi: 10.1086/674859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas JS, Patel A, Otter JA, Wade P, Newsholme W, van Kleef E, et al. Reduction in Clostridium difficile environmental contamination by hospitalized patients treated with fidaxomicin. J Hosp Infect. 2015 Jul;90(3):267–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethi AK, Al-Nassir WN, Nerandzic MM, Bobulsky GS, Donskey CJ. Persistence of Skin Contamination and Environmental Shedding of Clostridium difficile during and after Treatment of C. difficile Infection. Infect Control Amp Hosp Epidemiol. 2010 Jan;31(1):21–7. doi: 10.1086/649016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]