Abstract

The present study bridges the process and content perspectives of ethnic/racial identity by examining the longitudinal links between identity process (i.e., exploration, commitment) and a component of identity content, salience. Data were drawn from a four-wave longitudinal study of 405 ethnically/racially diverse adolescents (63% female) from 9th to 10th grade. Results identified a transactional relation between identity process over the long-term and content in daily experiences: adolescents with stronger ethnic/racial identity commitment reported higher daily mean salience and less variability in salience six months later. At the same time, adolescents who reported more daily variability in salience engaged in more exploration six months later; this was particularly evident among youth who reported lower levels of mean salience. While centrality moderated some associations, most of the longitudinal associations did not vary by centrality. Building off long-standing theories of identity development that distinguish the independent effects of exploration and commitment, the data suggest that commitment predicts daily ethnic/racial salience experiences, while exploration is predicted by daily salience. Moreover, daily salience seems to serve as a developmental mechanism informing the construction of ethnic/racial identity over time. Implications for ethnic/racial identity development are discussed.

Keywords: ethnic/racial identity, process, content, longitudinal

The development of ethnic/racial identity (ERI) is a key task for many ethnic/racial minority youth and can be a central theme in their daily experiences (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Positive feelings about one’s ERI are linked to socioemotional, academic, and behavioral well-being among young people (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). As a result, researchers have paid particular attention to the ERI of youth. Yet, despite extensive research, the literature on the developmental importance of ERI lacks a coherent and unified approach. The current literature on ERI has its foundations in two disparate perspectives: a developmental process perspective and a content perspective. The developmental process perspective highlights two processes that occur over time: exploring the meaning of one’s ethnicity/race (i.e., exploration) and establishing a clear sense of its meaning (i.e., commitment; Phinney, 1989; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). On the other hand, the content perspective, highlights ERI components, such as the extent to which youth are aware of this aspect of identity from situation to situation (i.e., salience), the extent to which ERI is important to youth overall (i.e., centrality), and the positive feelings youth have about their ethnic/racial group membership (i.e., private regard; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Although both process and content are key dimensions of ERI and interact in developmentally meaningful ways, they have been studied almost exclusively in parallel with little consideration of the ways in which they intersect and influence one another. This gap has been noted in theoretical work (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), yet scholars have only recently begun to synthesize these two approaches empirically (Syed & Azmitia, 2008; Yip, 2014). Building upon theoretical and integrative models of ERI (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), the current study provides empirical linkages between the process and content approaches in service of a comprehensive understanding of how adolescents who are at different places in their ERI development (i.e. process) might have different experiences of ethnicity/race in their daily lives (i.e., content). At the same time, a combined approach will also elucidate how adolescents’ daily experiences of ethnicity/race (i.e., content) impact their long-term ERI development (i.e., process). As such, the study investigates the reciprocal associations between ERI process and content over time.

Research has begun to link the ERI process of exploration and commitment to its content, such as salience (Yip, 2014) and centrality (Kiang, Witkow, Baldelomar, & Fuligni, 2010; Syed & Azmitia, 2008; Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). The current literature, however, is limited to cross-sectional studies (see Syed & Azmitia, 2010 for an exception), precluding the investigation of directional and reciprocal associations between ERI process and content. Thus, whether ERI exploration and commitment determines how one experiences ERI from situation to situation, or whether one’s experience of ERI at the situation level prompts long-term exploration and commitment, or whether both are operative, remains unknown. To address this gap, the present study examines the longitudinal associations between identity processes (i.e., exploration, commitment) and a particular component of identity content, salience (Sellers et al., 1998). Salience has particular developmental relevance because it is considered to be the mechanism through which ERI becomes relevant in daily life, thus facilitating the construction of a trait-like ERI over time (Yip & Douglass, 2013). The study also considers another dimension of content, centrality, defined as individual differences in the importance of ethnicity/race. Since centrality has been observed to be an important individual difference in ERI experiences (Douglass, Yip & Shelton, 2014; Yip, 2005) and not shown to change during adolescence (Seaton, Yip, & Sellers, 2009), the study considers possible differences in the above longitudinal associations by individual differences in centrality.

The Process and Content of Ethnic/Racial Identity in Adolescence

Adolescence is a particularly important time for ERI development, due in part to the parallel development of cognitive abilities that are necessary to understand the meaning of ethnicity/race and its increasing significance in social interactions (Cross & Cross, 2008; Quintana, 1998). Adolescence is also a period when young people spend less time with family and more time in ethnically/racially diverse environments such as school or work (Brown & Larson, 2009; Larson & Verma, 1999; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). These cognitive and sociocultural changes result in adolescents grappling with defining themselves and constructing a new identity (Erikson, 1968).

A process approach to ERI development stems from theories of ego identity development (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1980) and aims to chart the developmental processes through which youth explore and determine the meaning of ethnicity/race in their lives (Phinney, 1989). Exploration refers to behavioral and cognitive attempts to seek information about one’s ethnicity/race, whereas commitment refers to an attachment to one’s ethnic/racial group. By documenting one’s levels of exploration and commitment, the process approach to ERI development aims to chart developmental progression over time. Accordingly, youth are expected to move from a “less” developed identity status (e.g., low exploration, low commitment) to a “more” developed identity status (e.g., commitment after exploration) over time (Phinney, 1989). Indeed, empirical work has documented substantial changes in adolescents’ exploration and commitment (Huang & Stormshak, 2011; Kiang et al., 2010), particularly during the transition to high school (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006), and even in to adulthood (Yip, Seaton & Sellers, 2006). The present study focuses on the transition period to high school and investigates adolescents’ ERI exploration and commitment twice a year from 9th grade to 10th grade.

Complementing the developmental perspective afforded by an ERI process approach, the content approach offers a social/personality perspective highlighting individual experiences of ethnicity/race at a given time point (Sellers et al., 1998; Yip, 2014). The content perspective delineates the salience, significance, and meaning of ethnicity/race for individuals’ self-concept from situation to situation (Sellers et al., 1998; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Salience refers to the extent to which ethnicity/race is relevant for one’s self-concept in a particular situation. Although an ERI component, salience is not synonymous with ERI. In fact, one can be aware of membership in an ethnic/racial group, without having a strong or well-developed ERI. As such, being aware of one’s ethnicity/race does not implicate the affective or evaluative attitudes that are associated with having an ERI. Rather, salience functions as the gateway through which other components of identity content (e.g., private regard, public regard) become accessible to individuals in that situation (Sellers et al., 1998).

This study bridges the process and content approaches and considers salience to be the developmental mechanism through which ethnic/racial group membership has relevance in daily life, thus providing a psychological conduit through which ERI develops over time (Yip & Douglass, 2013). Salience arises as a function of personal characteristics, characteristics of the context, or more often than not, an interaction of the person in context. Thus, while salience is affected by one’s stable tendencies to think about ethnicity/race across situations, it is by nature a situational, dynamic construct sensitive to contextual cues which serves to render ethnicity/race more or less relevant (Sellers et al., 1998). For example, prior work has identified contextual factors such as ethnic composition, presence of family members, and language to be related to changes in salience from one moment to the next (Yip, 2005). Thus, salience varies from situation to situation and person to person. Prior work using daily dairy data have identified both individual differences in one’s average level of salience across situations as well as within-person changes in salience on a daily basis (Yip, 2005, 2009; Yip & Douglass, 2013; Yip & Fulgni, 2002). As such, the present study utilizes an experience sampling design to capture the between- and within-person components of salience.

Although prior work has acknowledged within-person variations in reports of ethnic/racial salience, scholarship has only recently started to examine the implications of salience variability – how ethnic/racial salience varies from one situation to the next, or from one day to the next. Exploring variability in salience provides unique insight into the developmental importance of salience, as it provides a sense of how consistently an adolescent thinks about ethnicity/race across a variety of settings. Using an experience sampling design that examined adolescents’ experiences of ethnicity/race five times a day across seven days, prior work (citation blinded for review) investigated variations in adolescents’ ethnic/racial salience from situation to situation, and linked these variations to adolescents’ daily mood and their concurrent levels of ERI exploration and commitment. Extending this research, the present study draws from the same dataset to examine both the mean level and variability of adolescents’ ethnic/racial salience, and more importantly, how mean levels and variability are related to ERI exploration and commitment longitudinally.

While both process and content are meaningful components of ERI, these two perspectives have rarely been investigated simultaneously. Thus, we currently know little about how adolescents who differ on the extent to which they have engaged in ERI processes experience the content of identity in their daily lives. More importantly, we do not yet understand how the two components develop in parallel across adolescence. Building off of prior work, the current study integrates the ERI process and content perspectives by investigating the longitudinal relations among exploration, commitment, mean salience, and variability in salience. We first review existing work that has examined the process-content linkages, and then discuss the theoretical basis for examining the longitudinal relations between ERI process and content.

Longitudinal Relations among Exploration, Commitment, and Mean Salience and Variability

While some theoretical work has linked ERI process and content and called for investigations of their longitudinal associations (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), empirical work has almost exclusively employed cross-sectional data. In a sample of African American, Latino, and Asian American adolescents (citation blinded for review), salience was associated with ERI status (i.e., combinations of high/low exploration and commitment), such that youth who had explored and made a commitment to their ERI also reported higher salience. Focusing on salience variability, prior work (citation blinded for review) found that the extent to which adolescents’ awareness of their ethnicity/race (i.e., salience) varied from situation to situation was concurrently associated with commitment, but not exploration, such that youth with greater commitment were more consistently aware of their identity. However, the cross-sectional data precluded the investigation of directionality between ERI process and content. Using longitudinal data, Syed and Azmitia (2010) investigated parallel changes in ERI process (i.e., exploration) and content (i.e., narratives of ethnicity-related experiences) over time. Yet, it is still unclear whether ERI processes shape how adolescents perceive ethnicity/race in their daily lives, or whether adolescents’ daily experiences influence the developmental process of ERI, or whether this association is more synergistic. The present study draws upon developmental theories to explore these possibilities.

On the one hand, ego identity theories highlight identity as a foundation that guides one’s daily experiences (Erikson, 1968) such that the developmental process of ERI (i.e., exploration, commitment) may influence adolescents’ situational experience of salience. Similarly, the content perspective posits that one’s tendency to define oneself based on ethnicity/race determines, may in part, influence the extent to which one is aware of ethnicity/race in a given situation (Sellers et al., 1998). For this reason, adolescents who have engaged in greater exploration and have higher levels of ERI commitment may think about ethnicity/race more consistently across situations; and thus, experience consistently high salience across situations (i.e., high average salience, low variability). This hypothesis is also supported by research on affect variability, where stable characteristics such as agreeableness and self-esteem are associated with more positive, and less variable affect across situations (Kuppens, Van Mechelen, Nezlek, Dossche, & Timmermans, 2007).

On the other hand, salience in daily interactions may also serve as a critical mechanism through which ERI develops (Yip & Douglass, 2013). Theories of identity development assert that individuals’ identities evolve through daily interactions with others (Adams & Marshall, 1996; Erikson, 1968), and that daily interactions prompt ERI development when ethnicity/race is salient (Sellers et al., 1998). Moreover, both theoretical and empirical work find that adolescents’ ethnically/racially-salient social interactions (e.g., interaction with intraracial and interracial peers, family cultural socialization) inform subsequent ERI exploration and commitment (Hughes, Hagelskamp, Way, & Foust, 2009; Kiang & Fuligni, 2008; Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001), highlighting the influence of salience on ERI development. Thus, we propose that high levels of mean salience may promote and trigger the processes of ERI exploration and commitment.

It is less clear how variability in salience might influence ERI development. Developmental theories often stress the role of stable, consistent social factors in promoting development (Adam, 2004; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Work on intra-individual variability also suggests that short-term variability in psychological experiences may accumulate to disturb well-being (Houben, Van Den Noortgate, & Kuppens, 2015; Wichers, 2014). With respect to ERI, stability in salience across situations may promote identity development, and salience variability may be associated with lower levels of subsequent exploration and commitment. In contrast, research that takes a more dynamic perspective posits variability as a critical mechanism for development (i.e., dynamic systems theory; Lewis, 2000; Smith & Thelen, 2003). Based on this theory, development takes place in a phase of high variability that allows for reorganization of thoughts and behaviors from the initial status to a more developed stage. Thus, adolescents who experience changes in salience across situations may be prompted to explore and think about the meaning of their ERI. Moreover, daily changes in salience may be especially influential for adolescents who typically experience low levels of salience because they are oscillating from a state of not thinking about their ethnicity/race to an experience of salience. Acknowledging that variability is inherently related to average levels, the present study examines the main effects of mean salience and variability, as well as their interaction, on ERI developmental processes.

The Moderating Role of Individual Characteristics: Centrality

Not all youth decide that ethnicity/race is central aspect in their lives (Charmaraman & Grossman, 2010; Kiang, Yip, & Fuligni, 2008). A comprehensive understanding of developmental processes involves the investigation of individual differences (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Thus, the present study examines whether the longitudinal relations between ERI process and content vary by individual differences in centrality – the importance of ethnicity/race to one’s identity. The ERI content perspective highlights centrality as a critical factor in understanding the differential implications of ERI on social interactions and daily experiences (Sellers et al., 1998). Indeed, empirical work demonstrates that individuals with high centrality are more likely to interpret daily experiences such as family socialization and stereotypes to have a stronger impact on individuals with high centrality than on those with low centrality (Burrow & Ong, 2010; Shelton & Sellers, 2000; Yip, 2005). Thus, we hypothesize that longitudinal relations between ERI process (i.e., exploration, commitment) and daily experiences of ethnicity/race (i.e., mean salience and variability) will be stronger for adolescents reporting higher ERI centrality.

The Present Study

The present study utilizes data from a longitudinal, experience sampling study to investigate relations between ERI process and content over time. We focused on the period from 9th to 10th grade due to the importance of this time for ERI development after the transition to high school, when youth tend to be exposed to a more diverse social environment. The present study has three research aims. First, we investigate the extent to which ERI exploration and commitment are associated with the mean levels and variability of salience over time. We hypothesize that higher levels of exploration and commitment will be subsequently linked to higher average levels of salience, but less variability. The second aim examines the extent to which salience level and variability are associated with subsequent ERI exploration and commitment over time. We propose a positive association between average salience on ERI exploration and commitment six months later. Because theory predicts that salience variability may either compromise or promote ERI development, we do not pose directional hypotheses for this effect. The final research aim explores the extent to which the longitudinal relations among ERI exploration, commitment, and salience vary by individual differences in ERI centrality, with the prediction that these associations will be stronger for youth with higher centrality.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a larger longitudinal study conducted in five New York City public high schools with varying ethnic/racial compositions. The five schools included a predominantly (i.e., greater than 40% of the student population) White school, a predominantly Asian school, a predominantly Hispanic school, and two ethnically/racially heterogeneous schools. Data collection occurred in each fall and spring semesters when students were in 9th to 11th grade (Waves 1 to 6). Two cohorts of students participated (Cohort 1 n = 248, Cohort 2 n = 157).

The present study used data from Waves 1 to 4 (9th fall, 9th spring, 10th fall, 10th spring). The analytic sample included 405 adolescents who participated in the first wave of the project. In the following three waves, 366, 315, and 301 adolescents from the initial sample participated, representing 74% retention across the 2 years. We did not include data from Waves 5 and 6 in consideration of missing data. Because one school declined to participate after the first cohort at Wave 5 and because of attrition, there were only 162 and 153 students in Waves 5 and 6, respectively. The sample includes 63% female participants. Adolescents’ mean age was 14.16 (SD = .43) at Wave 1. The sample is ethnically/racially diverse (12% African Americans, 25% Latino, 34% Asian Americans, 23% White, and 5% other ethnicity and race). Some adolescents (17%) were born outside of the United States. For these adolescents, age of immigration ranged from 6 months to 14 years, and the largest proportion emigrated from China (5%), followed by Bangladesh, Colombia, Ecuador, and the Philippines (1%, respectively). A considerable portion of the students reported not knowing the highest level of education completed by their parents (40%) while the next most common response was that their parents completed high school (17%).

Attrition analyses were conducted to compare demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, minority status, nativity) and study variables at Wave 1 between adolescents who participated in all the four waves with those who did not participate in at least one of the waves. The only difference between the two groups was that females were more likely than males to participate in all the waves (χ2 (1) = 5.20, p < .01). This differential attrition pattern was addressed by including gender as a covariate in all the analyses (Widaman, 2006).

Procedure

The research team identified five public schools in New York City with varying levels of ethnic/racial composition of the student body. Once the schools agreed to participate in the study, parental consent and youth assent letters were sent home to all 9th graders in the fall of 2008 and 2009, drawing in two cohorts of participants. Only students with completed consent and assent forms participated in the study. Data collection occurred in four waves: fall 9th grade, spring 9th grade, fall 10th grade, and spring 10th grade (Waves 1 to 4). At Wave 1, students were administered surveys in groups ranging from 5–25 students. After completing the surveys, participants were given a cellular phone to complete experience-sampling reports for the next seven days. Experience sampling designs are sensitive to both individual differences and situational cues, and thus are best suited to capture both within and between person effects (Yip & Douglass, 2013). To avoid disruption of academic time, participants were randomly prompted after school hours to complete brief surveys five times per day for a week for a total of 35 surveys. On average, participants completed 24 (range from 1 to 34) surveys over the course of the week. At Wave 2, participants completed a second round of surveys using parallel procedures to those in Wave 1, but were not given cell phones and did not complete experience-sampling reports. At Wave 3, participants completed both surveys and repeated the experience-sampling procedure. Similar to Wave 1, on average, participants completed 23 (range from 1 to 35) surveys over the course of the week. At Wave 4, participants completed a final round of surveys. Participants were compensated $50 after Wave 1 and $70 after Wave 3, and $20 after Waves 2 and 4. Attrition was 26% over the 18-month course of the study.

Measures

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among primary study variables are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Primary Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W1 Salience Mean | .76*** | −.45*** | −.19 ** | .14*** | .08 | .10** | .10* | .19** | .12* | .14** | .19** | .19*** | .17*** | .13* | .22*** | |

| 2. W3 Salience Mean | −.34*** | −.37*** | .10 | .08 | .08 | .09* | .15** | .18** | .21*** | .24*** | .14** | .20*** | .20*** | .25*** | ||

| 3. W1 Salience Variability | .30*** | −.06* | −.02 | −.08** | −.07* | −.09 | −.04 | −.13*** | −.20** | −.11** | −.08 | −.06 | −.14*** | |||

| 4. W3 Salience Variability | −.05 | .01 | −.08 | .02 | −.11 | −.05** | −.15 | −.13 ** | .01 | −.04 | −.04 | −.14 | ||||

| 5. W1 Exploration | .57*** | .48*** | 49*** | .55*** | .36*** | .33*** | .39*** | .41*** | .38*** | .31*** | .35*** | |||||

| 6. W2 Exploration | .58*** | .64*** | .41*** | .60*** | .38*** | .49*** | .46*** | .55*** | .41*** | .46*** | ||||||

| 7. W3 Exploration | .63*** | .30*** | .38*** | .56*** | .42*** | .37*** | .41*** | .49*** | .45*** | |||||||

| 8. W4 Exploration | .42 | .42*** | .40*** | .63*** | .44*** | .41*** | .42*** | .50*** | ||||||||

| 9. W1 Commitment | .46*** | .39*** | .44*** | .53*** | .38*** | .35*** | .32*** | |||||||||

| 10. W2 Commitment | .53 | .55*** | .40*** | .50*** | .38*** | .40*** | ||||||||||

| 11. W3 Commitment | .51*** | .29*** | .41*** | .51*** | .41*** | |||||||||||

| 12. W4 Commitment | .45*** | .45*** | .44*** | .56*** | ||||||||||||

| 13. W1 Centrality | .56*** | .52*** | .55*** | |||||||||||||

| 14. W2 Centrality | .66*** | .62*** | ||||||||||||||

| 15. W3 Centrality | .67*** | |||||||||||||||

| 16. W4 Centrality | ||||||||||||||||

| N | 390 | 308 | 382 | 302 | 403 | 366 | 315 | 301 | 403 | 366 | 315 | 301 | 403 | 366 | 315 | 301 |

| Mean | 4.34 | 4.22 | .94 | .93 | 2.61 | 2.68 | 2.65 | 2.70 | 2.97 | 2.95 | 2.93 | 2.96 | 4.24 | 4.30 | 4.31 | 4.30 |

| SD | 1.62 | 1.63 | .61 | .58 | .54 | .51 | .49 | .49 | .44 | .42 | .40 | .40 | .93 | .81 | .80 | .82 |

Note: Estimates were obtained from Mplus that used based full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to handle missing data and generated estimates based on the entire sample.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Ethnic/Racial Identity Process

ERI exploration and commitment were measured at all waves (Waves 1 to 4) using the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999). Exploration refers to the extent to which one seeks information and experiences relevant to one’s ethnic/racial group membership. The exploration subscale includes five items; for example, “I have spent time trying to find out more about my own ethnic/racial group, such as history, traditions, and customs.” Commitment refers to the extent to which one feels attached and personally invested as a member of one’s ethnic/racial group. The commitment subscale includes seven items; for example, “I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic/racial group.” Participants responded to all items using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The reliability of each subscale was acceptable across waves (αrange = .72 to .74 for exploration, αrange = .85 to .87 for commitment). Tests for longitudinal measurement equivalence (see Table 2) showed that both ERI exploration and commitment achieved configural, metric, and strong factorial invariance across the four waves, suggesting that changes observed in these variables over time are developmentally meaningful and not measurement artifacts (Chen, 2008).

Table 2.

Longitudinal Measurement Invariance for Ethnic/Racial Identity Exploration, Commitment, and Centrality

| Model Fit Indices

|

Model Comparisons

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Invariance Levels | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | Invariance Achieved |

| Exploration | Configural | 173.391 | 129 | .979 | .969 | Yes | |||||

| Metric | 187.616 | 141 | .978 | .970 | 14.225 | 12 | .287 | .001 | −.001 | Yes | |

| Strong | 217.465 | 153 | .969 | .962 | 29.849 | 12 | .003 | .009 | .008 | Yes | |

| Strict | 247.052 | 168 | .962 | .957 | 29.587 | 15 | .014 | .007 | .005 | No | |

| Commitment | Configural | 485.538 | 294 | .954 | .941 | Yes | |||||

| Metric | 502.550 | 312 | .954 | .945 | 17.012 | 18 | .522 | .000 | −.004 | Yes | |

| Strong | 531.237 | 330 | .952 | .945 | 28.687 | 18 | .052 | .002 | .000 | Yes | |

| Strict | 563.583 | 351 | .949 | .945 | 32.346 | 21 | .054 | .003 | .000 | No | |

| Centralitya | Configural | 654.172 | 374 | .929 | .906 | Yes | |||||

| Metric | 681.332 | 395 | .928 | .909 | 27.160 | 21 | .166 | .001 | −.003 | Yes | |

| Strong | 758.340 | 416 | .914 | .897 | 77.008 | 21 | .000 | .014 | .012 | No | |

Note. Longitudinal factorial invariance was tested across four levels from the least restrictive to the most (configural, metric, strong, and strict; Widaman, Ferrer, & Conger, 2010). Configural invariance is established if the same set of items load well on the latent factor. Metric invariance exists if the factor loading of each item is invariant over time. Strong invariance can be achieved if the intercept of each item (i.e., the mean) is invariant over time. Finally, strict invariance exists if the residual variance of each item shows over-time invariance. Each invariance level was established if its model fit did not differ significantly from that of the previous invariance level and at least two of the following three criteria were met: Δχ2 significant at p < .05, ΔCFI ≥ .01 and Δnon-normed fit index ≥ .02 (Schwartz et al., 2011; see Cheung & Rensvold, 2002, for a discussion of criteria).

We did not proceed to test strict invariance for centrality because strong invariance was not achieved.

Ethnic/Racial Salience

Adolescents’ awareness of their ethnicity/race in a given situation was assessed at Waves 1 and 3 in the experience-sampling component of the study. At each wave, participants rated a single item of salience (i.e., “How aware are you of your ethnicity/race right now?”) five times a day for seven days. They also completed a number of other filler items that assessed salience of other social identities (e.g., gender, friend, student, etc.) to deflect attention from the focus on ethnicity/race. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely).

To assess each adolescent’s mean level and variability of salience, we used a multilevel structural equation modeling approach (Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010) to aggregate each adolescent’s reports across situations. We estimated the mean and variability of salience for participants who had at least two assessments of situational salience across the course of the study (average number of assessment = 24, SD = 10 at Wave 1; average number of assessment = 23, SD = 11 at Wave 2). Within each of Waves 1 and 3, we estimated a situation-level component and a person-level component of salience. To adjust for method artifacts arising from the intensive repeated measures, prompt order (i.e., 1st to 5th beep throughout a day), day order (i.e., 1st to 7th day in the study), and weekday indicators (0 = weekday, 1 = weekend) were included as a predictor of situation-level salience. At Wave 1, adolescents reported lower salience on weekends (standardized β = −.03, SE = .01, p < .05). At Wave 3, adolescents reported lower salience for successive prompts within a day (standardized β = −.03, SE = .01, p < .05) and for successive days within the study (standardized β = −.05, SE = .02, p < .05). The average salience for each student was estimated by the person-level mean value of salience. Salience variability for each student was estimated by the residual variance of situation-level salience (Dyer, Day, & Harper, 2014). While situational variability can be assessed by other approaches (e.g., average differences in consecutive situations, autocorrelation between consecutive situations), a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that these other approaches yielded similarly moderate associations between variability and well-being (Houben et al., 2015). The intraclass correlation for situational salience was .69 at Wave 1 and .72 at Wave 3, indicating both within- and between-person similarities and variability in reports across situations.

Ethnic/Racial Identity Centrality

ERI centrality was measured using an 8-item scale at all waves (Waves 1 to 4). We only used data from Waves 1 to 3 that were pertinent to the goals of the present study. As others have done (e.g., Fuligni, Witkow, & Garcia, 2005), we adapted the centrality subscale of the Multidimentional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997) for our multi-ethnic sample. Adolescents rated the importance of ethnicity/race to their overall self-concept (e.g., In general, my ethnicity/race is an important part of my self-image) using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The reliability of the centrality measure was acceptable across waves (αrange = .67 to .76). Similar to other work (Seaton et al., 2009), adolescents’ reports of centrality were largely stable over time (M = 4.23, SD = .93 at Wave 1; M = 4.30, SD = .82 at Wave 2; M = 4.31, SD = .80 at Wave 3). Tests for longitudinal measurement equivalence (see Table 2) showed that ERI centrality achieved configural and metric factorial invariance, but not strong invariance across the four waves, suggesting that while it is appropriate to compare relationships between centrality with other variables over time, changes observed in centrality may be due to measurement nonequivalence and should be interpreted with caution. Since the current study considers centrality to be an individual difference and not a time-varying covariate, the results of the invariance analyses were not concerning.

Covariates

Adolescents reported their ethnicity/race with the following categories: Asian American, African American, Latino, White, and other ethnicity/race, which was converted to minority status (0 = White, 1 = ethnic/racial minority). We also controlled for gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and cohort in the analyses.

Results

All analyses were conducted in a structural equation framework in Mplus 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2016). We used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to handle missing data. The non-independence of data (i.e., students nested in schools) was addressed by the Cluster feature in Mplus.

Descriptives of Ethnic/Racial Identity Process and Content over Time

We first investigated changes in ERI process and content over time. For exploration and commitment, we investigated changes in each variable across Waves 1 to 4 using latent growth modeling. For each ERI component, we fitted a linear model and a curvilinear model. For exploration across Waves 1 to 4, there was no significant difference in model fit between the linear and quadratic models (Δχ2(1) = .32, p = .57), therefore the more parsimonious, linear model was retained. Initial levels of exploration were just higher than neutral (unstandardized b = 2.63, SE = .03, p < .001, on a scale of 1 to 4) and increased over time (unstandardized b = .02, SE = .01, p < .05). For commitment, the model fit between the linear and quadratic models did not differ significantly (Δχ2(1) = 1.81, p = .18), therefore the linear model was retained. Initial levels of commitment were moderately high (unstandardized b = 2.96, SE = .02, p < .001, on a scale of 1 to 4) and did not change significantly over time (unstandardized b = −.01, SE = .01, p = .52).

Despite reservations related to measurement equivalence, to offer the most comprehensive analyses, we also explored centrality over time using latent growth modeling. Because no significant difference was observed for the model fit between the linear and quadratic models (Δχ2(1) = 1.64, p = .20), we adopted the more parsimonious, linear model. Initial levels of centrality were higher than neutral (unstandardized b = 4.27, SE = .04, p < .001, on a scale of 1 to 7) and did not change significantly over time (unstandardized b = .02, SE = .01, p = .30).

Regarding changes in mean salience and variability, we estimated a latent difference score from Waves 1 to 3 for each salience component (McArdle, 2009). We observed a significant decrease in the mean levels of salience over time (unstandardized b = −.14, SE = .06, p < .05). In contrast, there were no significant differences in salience variability between Waves 1 and 3 (unstandardized b = .01, SE = .04, p = .90).

Longitudinal Relations among Exploration, Commitment, and Salience Level and Variability

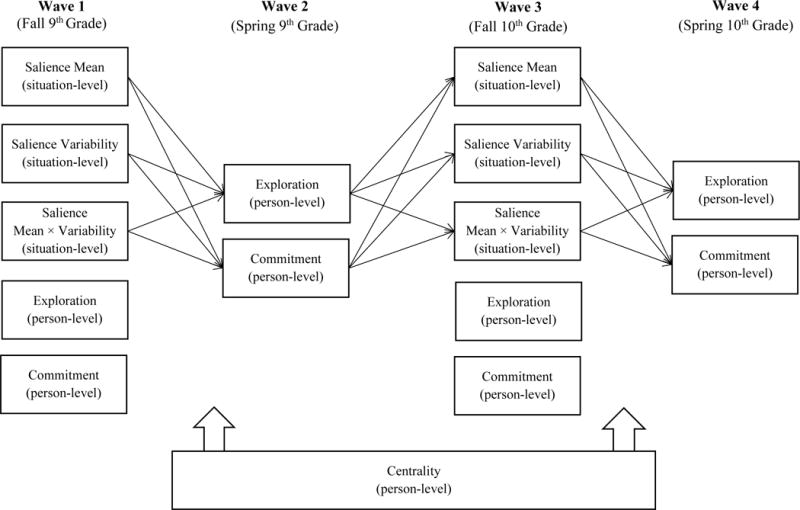

Our primary analyses tested the hypothesized model in Figure 1 using path analyses. In addition to relations of interest among exploration, commitment, and salience, we also estimated stability paths between sequential assessments (e.g., commitment from Waves 1 to 2), prior-wave controls between process variables and between salience variables (e.g., Wave 1 commitment to Wave 2 exploration), and covariances among all variables measured concurrently.

Figure 1.

Full path analysis model for relations among exploration, commitment, and salience level and variability. Stability paths, prior wave controls, and within wave covariances were included in the model but are not depicted here.

Because we did not have a priori hypotheses regarding whether the same longitudinal associations would differ over time (e.g., mean salience to exploration from Waves 1 to 2 versus Waves 3 to 4), we tested a time-invariant model in which cross-lagged relations of interest were constrained to be equal over time. This more parsimonious model did not differ significantly in model fit (Δχ2(6) = 10.64, p = .10) to the freely estimated model, thus the time-invariant model was retained. The final model demonstrated a good model fit, χ2(df = 26, N = 405) = 29.38, p = .29, CFI = .998, RMSEA = .018, SRMR = .021.

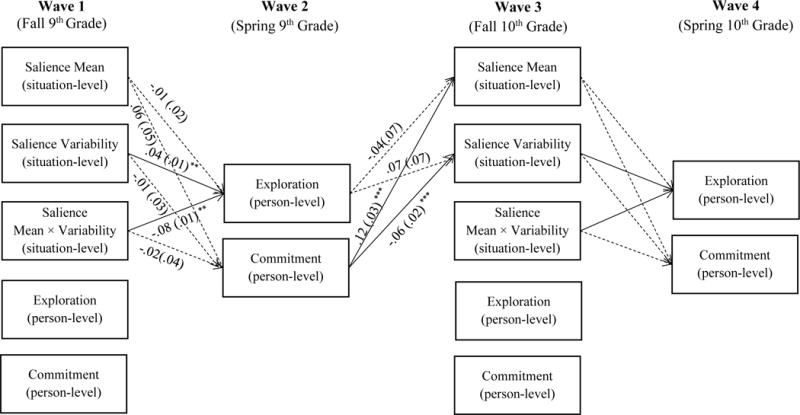

All relations of interest are shown in Figure 2. Because stability paths, prior-wave controls, and within-wave covariances are not central to our hypotheses, estimates for these relations are reported in Table 3. When a longitudinal effect between ERI content and process emerged as significant, we interpreted this effect in combination with the within-wave covariances between the same variables.

Figure 2.

Significant standardized coefficients and standard errors from path analysis for relations among exploration, commitment, and salience level and variability. Significant coefficients are depicted in solid lines; non-significant coefficients are depicted in dashed lines. Paths from Waves 3 to 4 were constrained to be equal with the same paths from Waves 1 to 2. Stability paths, prior wave controls, and within wave covariances are reported in Table 3. *p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p <.001.

Table 3.

Standardized Coefficient Estimates for Stability, Prior Wave Controls, and Within Wave Covariances from Path Analysis for Relations among Exploration, Commitment, and Salience Level and Variability

| β | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability paths | |||

| Exploration | |||

| W1 Exploration → W2 Exploration | .48 | .05 | *** |

| W2 Exploration → W3 Exploration | .41 | .08 | *** |

| W1 Exploration → W3 Exploration | .25 | .05 | *** |

| W3 Exploration → W4 Exploration | .36 | .05 | *** |

| W2 Exploration → W4 Exploration | .33 | .05 | *** |

| W1 Exploration → W4 Exploration | .04 | .06 | |

| Commitment | |||

| W1 Commitment → W2 Commitment | .37 | .05 | *** |

| W2 Commitment → W3 Commitment | .43 | .06 | *** |

| W1 Commitment → W3 Commitment | .14 | .06 | * |

| W3 Commitment → W4 Commitment | .23 | .03 | *** |

| W2 Commitment → W4 Commitment | .24 | .09 | ** |

| W1 Commitment → W4 Commitment | .14 | .04 | *** |

| Salience | |||

| W1 Salience Mean → W3 Salience Mean | .74 | .04 | *** |

| W1 Salience Variability → W3 Salience Variability | .27 | .03 | *** |

| W1 Salience Interaction → W3 Salience Interaction | .14 | .11 | |

| Prior wave controls | |||

| Commitment → Exploration | |||

| W1 Commitment → W2 Exploration | .14 | .04 | ** |

| W2 Commitment → W3 Exploration | .06 | .07 | |

| W1 Commitment → W3 Exploration | −.04 | .06 | |

| W3 Commitment → W4 Exploration | .00 | .05 | |

| W2 Commitment → W4 Exploration | .01 | .02 | |

| W1 Commitment → W4 Exploration | .14 | .05 | * |

| Exploration → Commitment | |||

| W1 Exploration → W2 Commitment | .15 | .05 | ** |

| W2 Exploration → W3 Commitment | .02 | .02 | |

| W1 Exploration → W3 Commitment | .09 | .07 | |

| W3 Exploration → W4 Commitment | .05 | .06 | |

| W2 Exploration → W4 Commitment | .13 | .01 | *** |

| W1 Exploration → W4 Commitment | .05 | .04 | |

| Salience | |||

| W1 Salience Variability → W3 Salience Mean | .01 | .02 | |

| W1 Salience Interaction → W3 Salience Mean | −.04 | .04 | |

| W1 Salience Mean → W3 Salience Variability | −.03 | .05 | |

| W1 Salience Interaction → W3 Salience Variability | .08 | .04 | * |

| W1 Salience Mean → W3 Salience Interaction | −.30 | .05 | *** |

| W1 Salience Variability → W3 Salience Interaction | −.06 | .10 | |

| Within wave covariances | |||

| Exploration ↔ Commitment | |||

| W1 Exploration ↔ W1 Commitment | .55 | .04 | *** |

| W2 Exploration ↔ W2 Commitment | .50 | .05 | *** |

| W3 Exploration ↔ W3 Commitment | .46 | .06 | *** |

| W4 Exploration ↔ W4 Commitment | .44 | .08 | *** |

| Exploration ↔ Salience | |||

| W1 Exploration ↔ W1 Salience Mean | .13 | .04 | ** |

| W3 Exploration ↔ W3 Salience Mean | .00 | .04 | |

| W1 Exploration ↔ W1 Salience Variability | −.05 | .02 | * |

| W3 Exploration ↔ W3 Salience Variability | −.08 | .04 | * |

| W1 Exploration ↔ W1 Salience Interaction | −.11 | .04 | * |

| W3 Exploration ↔ W3 Salience Interaction | .02 | .07 | |

| Commitment ↔ Salience | |||

| W1 Commitment ↔ W1 Salience Mean | .17 | .05 | ** |

| W3 Commitment ↔ W3 Salience Mean | .13 | .06 | * |

| W1 Commitment ↔ W1 Salience Variability | −.08 | .04 | * |

| W3 Commitment ↔ W3 Salience Variability | −.09 | .11 | |

| W1 Commitment ↔ W1 Salience Interaction | −.11 | .09 | |

| W3 Commitment ↔ W3 Salience Interaction | −.11 | .11 | |

| Salience | |||

| W1 Salience Mean ↔ W1 Salience Variability | −.43 | .04 | *** |

| W3 Salience Mean ↔ W3 Salience Variability | −.35 | .06 | *** |

| W1 Salience Mean ↔ W1 Salience Interaction | −.13 | .10 | |

| W3 Salience Mean ↔ W3 Salience Interaction | −.17 | .06 | ** |

| W1 Salience Variability ↔ W1 Salience Interaction | .07 | .07 | |

| W3 Salience Variability ↔ W3 Salience Interaction | .03 | .08 |

Note: Salience interaction represents the interaction between salience level and variability.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Exploration and commitment predicting mean salience and variability

Addressing the first research aim, we examined the longitudinal effects of ERI exploration and commitment at Wave 2 on salience mean and variability at Wave 3. For ERI exploration, no longitudinal effects on salience were observed, thus exploration did not predict subsequent salience mean or variability.

In contrast, commitment at Wave 2 was significantly related to both the salience mean and variability of salience at Wave 3. Specifically, adolescents who reported stronger ERI commitment reported higher average levels of salience, but less salience variability six months later. In other words, adolescents reporting stronger ERI commitment reported higher and more stable levels of salience six months later. These patterns were consistent with within-wave relations (see the lower portion of Table 3). Specifically, stronger commitment was associated with higher levels of salience at both Waves 1 and 3. Stronger commitment was also associated with less salience variability at Wave 1; this relation was in the same direction albeit not significant at Wave 3.

Mean salience and variability predicting exploration and commitment

Addressing the second research aim, we examined the longitudinal effects of mean salience, variability, and their interaction for exploration and commitment six months later. Effects from Waves 1 to 2 were constrained to be equal as those from Waves 3 to 4. We first report estimates from preliminary analyses that tested the main effects of mean salience and variability for exploration and commitment. We then present findings from our primary analyses that included the interaction term between mean salience and variability.

In the preliminary analyses, we did not observe longitudinal effects of ethnic/racial salience mean for either ERI exploration (β = −.01, SE = .02, p = .48) or commitment (β = .06, SE = .05, p = .17). In contrast, although ethnic/racial salience variability was not associated with later ERI commitment (β = −.01, SE = .03, p = .82), more salience variability was significantly linked to more ERI exploration six months later (β = .04, SE = .01, p = .001). These findings suggested that while salience mean did not predict subsequent ERI process, salience variability predicted subsequent ERI exploration.

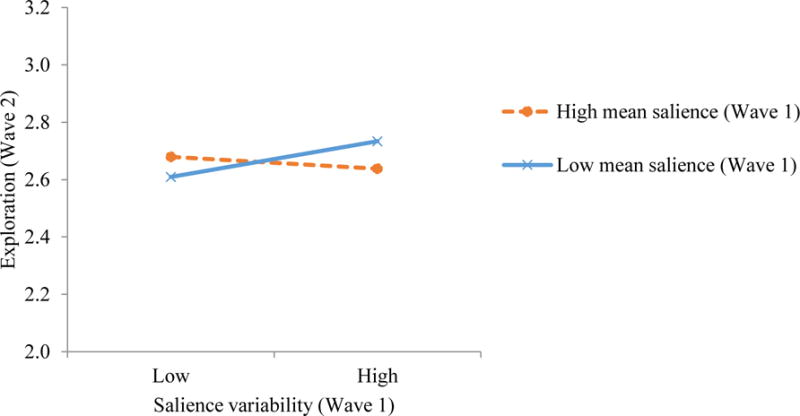

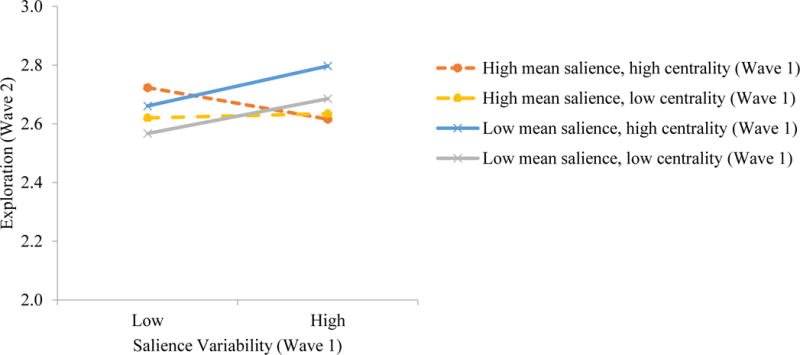

Building off of the main effects analyses, we pursued the primary goal of our second aim which was to investigate the interaction between salience mean and variability. While the interaction effect between mean salience and variability was not significant for subsequent ERI commitment, we observed a significant interaction between mean salience and variability for subsequent ERI exploration (see Figure 2). Simple slope analyses (Figure 3) demonstrated that for adolescents who reported lower mean levels of ethnic/racial salience (i.e., one standard deviation below the average), more variability in salience across situations was associated with more ERI exploration six months later (β = .14, SE = .05, p < .05). In contrast, for adolescents who reported higher mean levels of ethnic/racial salience (i.e., one standard deviation above the average), greater variability in salience across situations was not related to exploration six months later (β = .02, SE = .01, p = .16). In other words, ERI exploration increased over the six-month period among adolescents who reported lower average levels of salience and more variability across situations.

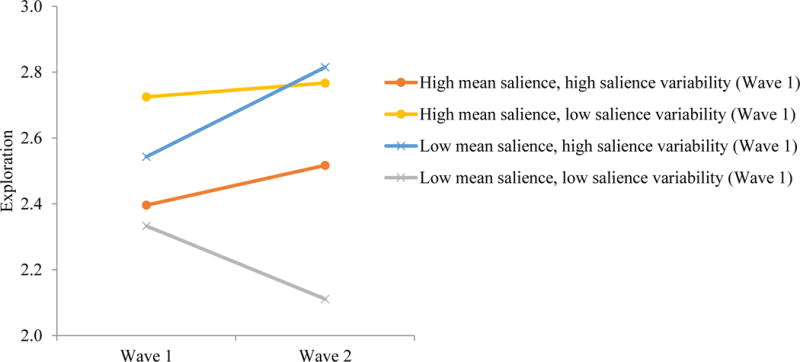

Figure 3.

Interaction effect of mean salience and salience variability at Wave 1 for exploration at Wave 2. High mean salience was assessed at one standard deviation above the mean, and low mean salience was assessed at one standard deviation below the mean. Solid lines indicate significant relations.

These longitudinal patterns differed from the cross-sectional associations between salience and exploration (see the lower portion of Table 3). In cross-sectional associations, higher levels of mean salience were associated with more exploration at Wave 1; less salience variability was associated with more exploration at both Waves 1 and 3. We suspect these inconsistencies capture how salience was differentially associated with the mean levels of exploration versus the change in exploration over time. To further disentangle this possibility, we examined descriptive statistics of ERI exploration over time as a function of salience mean and variability. Figure 4 illustrates ERI exploration at Waves 1 and 2 for adolescents with varying levels of salience mean and variability at Wave 1. Consistent with the within wave relations between salience and exploration, ERI exploration was the highest among adolescents who reported higher levels of mean salience and less salience variability. Moreover, ERI exploration was moderate among adolescents who reported lower average levels of salience and more variability across situations. However, this group of adolescents demonstrated greater increase in ERI exploration from Waves 1 to 2 than the other groups, which was consistent with the longitudinal interaction effect between salience mean and variability for exploration. As such, the descriptive statistics support the hypothesis that salience was differentially linked to concurrent ERI exploration versus change in ERI exploration over time.

Figure 4.

Descriptives of salience mean, variability, and exploration over time. Data from Waves 1 to 2 were used as an example. High levels of mean salience and variability were assessed at one standard deviation above the mean of each variable, respectively. Low levels of mean salience and variability were assessed at one standard deviation below the mean of each variable, respectively.

Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate the reliability of the analyses, three sets of sensitivity analyses were conducted. Estimates for our primary relationships of interests are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Standardized Coefficient Estimates from Sensitivity Analyses for Longitudinal Relations among Exploration, Commitment, and Salience Level and Variability

| Model S1 Freely estimated model |

Model S2 Alternative salience estimates 1 (n = 364) |

Model S3 Alternative salience estimates 2 (n = 355) |

Model S4 Estimates from Waves 1 to 6 (n = 212) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| Process → Content | ||||||||||||

| W2 exploration → W3 salience mean | −.04 | .08 | −.06 | .06 | −.02 | .06 | −.05 | .03 | ||||

| W2 exploration → W3 salience variability | .07 | .07 | .07 | .06 | .00 | .05 | .06 | .03 | ||||

| W2 commitment → W3 salience mean | .12 | .03 | *** | .11 | .03 | *** | .08 | .01 | *** | .16 | .05 | ** |

| W2 commitment → W3 salience variability | −.06 | .02 | *** | −.04 | .02 | * | −.02 | .03 | −.14 | .07 | * | |

| Content → Process | ||||||||||||

| W1 salience interaction → W2 exploration | −.12 | .05 | ** | −.07 | .02 | *** | −.08 | .02 | *** | −.10 | .05 | * |

| W1 salience interaction → W2 commitment | −.06 | .06 | −.01 | .04 | −.03 | .05 | −.03 | .04 | ||||

| W3 salience interaction → W4 exploration | −.03 | .02 | + | – | – | – | ||||||

| W3 salience interaction → W4 commitment | .02 | .05 | – | – | – | |||||||

Note: Salience interaction represents the interaction between salience level and variability. In Models S2 to S4, the same longitudinal path between process and content was constrained to be equal over time (e.g., W1 salience interaction → W2 exploration, W3 salience interaction → W4 exploration). Moreover, in Model S4, the same longitudinal paths involving Wave 5 and 6 were also constrained to be equal over time (e.g., W2 commitment → W3 salience mean, W4 commitment → W5 salience mean), although these paths were not displayed in the table.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Estimates from the freely estimated model

The first set of sensitivity analyses tested a freely-estimated model in which no constraints were imposed over the cross-lagged relations. The results of these analyses are consistent with the primary findings. Specifically, stronger ERI commitment at Wave 2 was associated with higher levels of mean salience and less salience variability at Wave 3, whereas ERI exploration was not predictive of later salience. Also consistent with our primary analyses, a significant interaction emerged between Wave 1 salience mean and variability for Wave 2 exploration, such that salience variability was positively associated with subsequent ERI exploration for adolescents who had lower levels of mean salience but negatively associated with subsequent exploration for adolescents who had higher levels of mean salience. We observed a similar, albeit marginally significant interaction between Wave 3 salience mean and variability for Wave 4 ERI exploration, such that salience variability was associated with subsequent exploration for adolescents with lower levels of mean salience but not related to subsequent exploration for adolescents with higher levels of mean salience.

Estimates using alternative assessments of salience

The second set of sensitivity analyses explored the reliability of our estimates as a function of missing experience-sampling data (i.e., missing data in situational reports of salience). Our primary analyses estimated salience variables for participants who had at least two experience sampling reports. In the sensitivity analyses, we tested our hypothesized model using two subsamples of adolescents. In the first approach, we estimated salience variables for participants who completed at least two assessments within each day for at least two days (n = 364). The results of this set of analyses were identical to the primary analyses. In the second approach, we estimated salience variables for participants who completed at least 50% of the assessments (i.e., 18 of 35 assessments; n = 355), which is the lower bound of average response rates for signal-contingent experience sampling studies (Christensen, Barrett, Bliss-Moreau, Lebo, & Kaschub, 2003; Otsuki, Tinsley, Chao, & Unger, 2008). The results of this set of analyses were nearly identical to the primary analyses with one exception: ERI commitment was not associated with later salience variability.

Estimates using data from Waves 1 to 6

The last set of sensitivity analyses tested the longitudinal associations between ERI content and process using a subsample of adolescents whose schools and cohorts remained in the larger project across six waves (n = 212). We introduced the additional Waves 5 and 6 to our hypothesized model, estimating the longitudinal effects of ERI process on salience (Waves 2 to 3, Waves 4 to 5) as well as the longitudinal effects of ethnic/racial salience on ERI process (Waves 1 to 2, Waves 3 to 4, Waves 5 to 6). The results of this set of analyses were again identical to the primary analyses.

In conclusion, the results of three sensitivity analyses were largely consistent with our primary findings, providing further support for the robustness of these findings.

Individual Differences in Centrality

To address the third and final research question, we investigated the extent to which ERI centrality moderated the longitudinal relations between exploration, commitment, and mean salience and variability. We first examined how centrality at Wave 2 interacted with ERI process at Wave 2 to influence subsequent salience at Wave 3. Two separate interaction terms at Wave 2 were created between centrality and commitment and between centrality and exploration. We then tested these interaction terms for their effect on adolescents’ mean salience and variability at Wave 3, respectively. No significant interaction effects emerged, indicating that the longitudinal effects of ERI process in spring 9th grade on salience six months later did not vary by the extent to which adolescents consider ethnicity/race a central component of their self-concept.

We next examined how ERI centrality at Wave 1 interacted with salience at Wave 1 to influence ERI process at Wave 2. Three interaction terms at Wave 1 were created: 1) centrality and mean salience, 2) centrality and salience variability, and 3) a three-way interaction of centrality, mean salience, and salience variability. We tested these interactions for exploration and commitment at Wave 2, respectively. A three-way interaction between centrality, mean salience, and salience variability at Wave 1 emerged for exploration at Wave 2 (β = −.09, SE = .03, p < .01). Simple slope analysis to probed this interaction effect among adolescents with high (i.e., one standard deviation above the average) versus low (i.e., one standard deviation below the average) levels of centrality, mean salience, and salience variability (see Figure 5). For adolescents who reported lower mean salience at Wave 1, while we observed a positive association between salience variability at Wave 1 and exploration at Wave 2 from the primary analyses, moderation analyses showed that this positive association was stronger for adolescents who had higher centrality (β = .14, SE = .06, p < .05) than adolescents who had lower centrality (β = .12, SE = .01, p < .001). For adolescents who reported higher mean salience at Wave 1, we did not observe a significant relation between salience variability at Wave 1 and exploration at Wave 2 from the primary analyses; this association was not significant for adolescents who had higher centrality (β = −.09, SE = .05, p = .07) than adolescents who had lower centrality (β = .01, SE = .06, p = .85). These findings indicate that the longitudinal effect of adolescents’ 9th grade salience on ERI exploration six months later was more evident for those who considered ethnicity/race as central to their identity.

Figure 5.

Interaction effect of centrality, mean salience, and salience variability at Wave 1 for exploration at Wave 2. High centrality was assessed at one standard deviation above the mean, and low centrality was assessed at one standard deviation below the mean. Similarly, high mean salience was assessed at one standard deviation above the mean, and low mean salience was assessed at one standard deviation below the mean. Solid lines indicate significant relations, whereas dashed lines indicate non-significant relations.

Finally, we examined how centrality at Wave 3 interacted with salience at Wave 3 to influence ERI process at Wave 4 using an identical approach. No significant interaction effects emerged, suggesting that the longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial salience in the 10th grade and identity process six months later did not vary by the extent to which adolescents consider ethnicity/race as central.

Discussion

The study of ERI among adolescents has been approached from two perspectives; one that emphasizes the developmental process of exploration and commitment, and another that emphasizes ERI content, including aspects such as salience. In an attempt to understand the reciprocal associations between where adolescents are in the ERI development and their everyday experiences of ethnicity/race, the current study bridges the two perspectives by examining the longitudinal associations between identity process (i.e., exploration, commitment) and a key developmental component of ERI content, salience. In particular, the study attends both to average levels and variability in salience across situations. Results demonstrated differential directionality in identity process and content. Specifically, adolescents with greater ERI commitment reported significantly higher average levels of salience, and less salience variability. In addition, adolescents who reported more variability in salience also reported more identity exploration six months later. We also observed important caveats in the longitudinal relation between salience variability and exploration: more variability in salience was associated with more subsequent exploration only for adolescents who reported lower levels of mean salience. Together, these longitudinal relations delineated a transactional association in which ERI process and content inform and influence each other over time: being attached to one’s ethnic/racial group impacts how adolescents subsequently experience ethnicity/race in their daily lives, and their daily experiences of ethnicity/race also prompt adolescents’ subsequent search for the meaning of ethnicity/race in their lives. While centrality moderated the longitudinal effect of salience on subsequent exploration, the majority of the associations did not vary by the extent to which adolescents consider ethnicity/race a central aspect of self-concept.

Differential Developmental Implications of Commitment versus Exploration

Although both exploration and commitment are considered to tap ERI processes, the current study suggests that they serve unique developmental functions. Importantly, ERI commitment seems to predict daily experiences of salience, while ERI exploration seems to be a product of daily salience. Specifically, ERI commitment emerged as a consistent predictor for both the mean and variability of salience across situations over time, yet we did not observe significant relations in the opposite direction. The longitudinal effect of ERI commitment on subsequent salience is consistent with prior cross-sectional work showing that adolescents who had an achieved ERI status (i.e., high levels of commitment and exploration) reported greater salience on average across situations (citation blinded for review) and that adolescents with greater commitment reported more stability (less variability) in salience across situations (citation blinded for review). The present study extended these findings by exploring the temporal order between ERI commitment and salience; developing a clear sense of what ethnicity/race means is predictive of how youths experience ethnicity/race in their everyday lives, even up to six months later. This is aligned with theories positing that stable individual characteristics determine, in part, the extent to which one is aware of one’s own ethnicity/race in a given situation (Sellers et al., 1998). We suspect that ERI commitment serves as an internal resource that youths draw upon, or a lens through which adolescents interpret their daily experiences. Adolescents who were more certain of, and attached to, the ethnic/racial aspect of their identity were more likely to be cognizant of when ethnic/racial themes were present in their daily lives, and there was a consistency to this experience across situations. Prior studies have highlighted commitment as a key component of ERI in determining adolescents’ well-being (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). The present study contributes to this body of work by demonstrating the critical role of ERI commitment in adolescents’ everyday experiences of ethnicity/race.

In contrast to commitment, ERI exploration seemed to serve a different developmental purpose. Rather than predicting experiences of salience, exploration was predicted by salience. We observed some longitudinal effects of salience for adolescents’ subsequent ERI exploration, yet exploration was not a significant predictor of subsequent salience. Specifically, adolescents reporting more variability in awareness of their ethnicity/race from one situation to another were more likely to explore the meaning of ethnicity/race later on; and this relation was especially evident for adolescents who were generally less aware of their ethnicity/race. This finding contributes to prior work that failed to identify a significant relation between salience variability and exploration using cross-sectional data (citation blinded for review). Although how adolescents perceive their daily experiences of ethnicity/race seems to be unrelated to their current ERI exploration, these experiences serve as a mechanism that stimulate later exploration activities. This finding echoes prior work that documents changes in exploration and adolescents’ lived experiences of ethnicity unfold in parallel over time (Syed & Azmitia, 2010). Indeed, these data support earlier assertions that salience is the everyday experience that serves as a mechanistic link for ERI development over time (Yip & Douglass, 2013). This finding is also consistent with Erikson’s (1968) notion that adolescents’ identity develops and evolves in response to their daily interactions with others (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Moreover, our finding identifies ERI exploration as a developmental process that may be triggered by adolescents’ daily experiences. These data underscore exploration as an essential component in the ERI developmental process (Marcia, 1980; Phinney, 1989).

Developmental Implications of Salience: Mean and Variability

The current study also underscores the role of daily variability in salience as an important aspect of ERI development. Consistent with dynamic systems theories highlighting the role of variability in stimulating the reorganization of thoughts and behaviors (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Thelen, 2003), these data suggest that the changing nature of one’s awareness of ethnicity/race is more likely to drive adolescents to question the meaning of ethnicity/race in their lives and engage in activities to search for such meanings. Theoretical work on ERI development posits increasingly diverse social contexts as a key factor that drives young people’s search for the meaning of ethnicity/race in their lives (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Prior work also identifies the changing ethnic/racial context in school as a mechanism that motivates exploration of ethnic/racial identity (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2000). The present study supports these assertions by demonstrating how variability in daily experiences of ethnicity/race stimulates adolescents’ ERI exploration over time. Our finding also contributes to the literature on identity development, which has identified a positive link between fluctuations in one’s daily experiences of interpersonal and ideological identities and subsequent reconsideration of these self-concepts (Klimstra et al., 2010). However, more work is needed to further unpack the developmental implications of variability. For example, the current study suggests that the promotive effect of salience variability for ERI exploration was more evident for adolescents who were generally not aware of their ethnicity/race across situations. Moreover, while adolescents who perceived more variability in their awareness of ethnicity/race across situations may be prompted to engage in more exploration activities, they may, at the same time, find it difficult to handle variability and inconsistency emotionally. In fact, prior work has often conceptualized variability as an indicator of instability and vulnerability, linking it to maladaptive outcomes such as internalizing and externalizing problems (Houben et al., 2015; Molloy, Ram, & Gest, 2011). Future studies should incorporate both identity development and psychological well-being as adjustment indicators to understand the impact of variability. Nonetheless, our findings highlight the utility of exploring variability as an important developmental construct.

In addition to variability, consistent with existing research, the mean levels of salience also matter for ERI development. How much adolescents were aware of their ethnicity/race, on average, in the fall of 9th grade (mean salience) conditioned the relation between variability in salience and adolescents’ subsequent ERI exploration. We suspect that salience variability may entail different meanings for these two groups. Adolescents who were generally unaware of their ethnicity/race in their daily lives, have not spent much time thinking about issues of ethnicity/race, and are likely in contexts which place little emphasis on such issues (e.g., adolescents with low levels of ethnic socialization from parents and friends). For these adolescents, experiences that render ethnicity/race salient are often more impactful as compared to adolescents who are typically grappling with such issues in their daily lives. As such, sudden and unexpected elevations in salience may prompt these adolescents to explore the meaning of ethnicity/race in their lives. Drastic changes in salience may serve as encounters that prompt low-salience youth to engage in a path of identity development (Cross & Cross, 2008; Cross, Parham, & Helms, 1991). On the other hand, adolescents reporting high levels of salience across situations are likely more experienced with issues of ethnicity/race and exposure to social environments where features of ethnicity/race are readily accessible (e.g., high levels of ethnic socialization from parents and friends). This is supported by the negative bivariate correlations between salience and variability, suggesting that adolescents who reported high levels of mean salience also reported more stable (less variable) salience across situations. For these adolescents, not being aware of their ethnicity/race may be a less positive experience (citation blinded for review), thus leading to a non-significant relation between salience variability and later exploration. Prior work on threshold effects has demonstrated that the effect of within-person variability in adolescents’ daily experiences (e.g., social stressors) on their adjustment is conditioned by the between-person mean level of these experiences (Zeiders, Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2015). Together, these data and prior research highlight the importance of considering mean levels and variability simultaneously to understand the developmental implications of variability. Future work is also needed to understand the social origins and individual factors that contribute to the mean level and variability of salience.

Variations by Centrality

The third and final aim of the present study was to examine whether the longitudinal relations between ERI process and content varied by the extent to which youths consider ethnicity/race to be central. Among the 18 possible associations tested in our hypothesized model, only one moderating effect of centrality emerged such that the longitudinal association between salience in the fall of 9th grade and exploration six months later was more evident for adolescents with higher centrality than for those with lower centrality. This is consistent with prior work that has observed the importance of centrality as an individual difference variable among young adult samples (Fuller-Rowell, Burrow, & Ong, 2011; Shelton & Sellers, 2000; Yip, 2005). However, it should also be noted that most of the relations tested in the present study did not vary by centrality. Perhaps the universal importance of identity development during adolescence renders individual differences less important. Instead, the transactional relations between ERI process and adolescents’ daily experiences of identity were observed for all youths regardless of levels of centrality; at least for the current sample of diverse adolescents residing in one of the most diverse areas of the United States.

Towards a More Dynamic Investigation of Ethnic/Racial Identity

In line with recent theoretical advances as proposed by the integrative ERI model (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), the present study bridged the process and content components by investigating longitudinal relations among exploration, commitment, and salience. Yet, by assessing ERI process in a survey design to capture long-term development and identity content in an experience-sampling design to capture situational experiences, these data also illustrated the synergistic association between the situational and developmental features of ERI. In fact, although theories of identity often suggest that identity evolves through daily experiences (Cross & Strauss, 1998; Erikson, 1968), little empirical work has examined how situational fluctuations of identity translate into long-term development. Recent work has also called for more attention to situational contexts in understanding ERI development (Verkuyten, 2016). Answering this call, the current data suggest that while adolescents’ ERI development (i.e., commitment) influences how they experience ethnicity/race in a particular situation (i.e., salience), situational variations (i.e., interaction between salience mean and variability across situations) are also important to consider for their role in prompting ERI development over time.

The investigation of situational-longitudinal linkages also calls for a more dynamic conceptualization of ERI. While our conceptualization of identity content as situational constructs and identity process as long-term development is consistent with theoretical work (Phinney, 1989; Sellers et al., 1998), both the content and process components of ERI may involve situational variations and long-term development. Indeed, recent research has also identified daily variations in identity process and its implications for identity formation (Becht et al., 2016; Klimstra et al., 2010). Consistent with theoretical formulations conceptualizing centrality as relatively stable, our data did not reveal a clear pattern of change in centrality, yet this was confounded by the inability to secure longitudinal measurement equivalence. Thus, the data leave open the question whether centrality changes during the transition to high school. While centrality did not exhibit changes in research focusing on adolescence (Seaton et al., 2009), work that targets adolescence to adulthood has identified an increase in centrality (Rivas-Drake & Witherspoon, 2013). Future work investigating ERI content and process on a daily basis and longitudinally will further inform the developmental mechanism of identity development.

Limitations and Conclusions

The current study’s findings should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. While the sample is ethnically/racially diverse, including non-Hispanic White youth and those from multiple minority groups, power limitations precluded analyses by adolescents’ ethnicity/race. Future studies with larger samples should consider ethnic/racial differences between identity process and content. Moreover, the present study examined changes in ERI process and content during the first two years in high school. While these two years capture drastic changes in social environment and adolescent well-being upon high school transition (Benner & Graham, 2009; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), they represent a relatively short period in adolescence. Future studies investigating a broader time span could further elucidate how ERI process and content unfold over time in a dynamic way.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to the existing literature on ERI by further integrating the study of process and content. Our findings delineate a transactional and synergistic association between ERI process and content, such that the developmental process of adolescents’ ERI influences their experiences of identity content in everyday life, and their daily experiences in turn promote the process of identity development. These process-content and situational-developmental dynamics are component-specific: daily experiences of salience were observed to beget further ERI exploration, while ERI commitment was observed to influence daily experiences of salience. Together, these findings also lend further support to the notion that daily experiences of salience are the developmental mechanism through which ERI is constructed and established as a stable and defining characteristic of adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of integrating the process and content perspectives to understand an important aspect of identity development for ethnically/racially diverse populations.

Contributor Information

Yijie Wang, Michigan State University.

Sara Douglass, OMNI Institute.

Tiffany Yip, Fordham University.

References

- Adam EK. Beyond quality: Parental and residential stability and children’s adjustment. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00310.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GR, Marshall SK. A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context. Journal of Adolescence. 1996;19:429–442. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Becht AI, Branje SJT, Vollebergh WAM, Maciejewski DF, van Lier PAC, Koot HM, Meeus WHJ. Assessment of identity during adolescence using daily diary methods: Measurement invariance across time and sex. Psychological Assessment. 2016;28:660–672. doi: 10.1037/pas0000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Graham S. The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development. 2009;80:356–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Handbook of child psychology (6th ed): Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Larson J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, Ong AD. Racial identity as a moderator of daily exposure and reactivity to racial discrimination. Self and Identity. 2010;9:383–402. doi: 10.1080/15298860903192496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaraman L, Grossman JM. Importance of race and ethnicity: An exploration of Asian, Black, Latino, and multiracial adolescent identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:144–1551. doi: 10.1037/a0018668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF. What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks? The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1005–1018. doi: 10.1037/a0013193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen TC, Barrett LF, Bliss-Moreau E, Lebo K, Kaschub C. A practical guide to experience-sampling procedures. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2003;4:53–78. doi: 10.1023/A:1023609306024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Cross TB. Theory, research, and models. In: Quintana SM, McKown C, editors. Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. pp. 154–181. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Parham TA, Helms JE. The stages of Black identity development: Nigrescence models. In: Jones RL, editor. Black psychology. 3rd. Berkeley, CA: Cobb & Henry Publishers; 1991. pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Strauss L. The everyday functions of African American identity. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The target’s perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 267–279. [Google Scholar]