Abstract

The tumour microenvironment is the primary location in which tumour cells and the host immune system interact. Different immune cell subsets are recruited into the tumour microenvironment via interactions between chemokines and chemokine receptors, and these populations have distinct effects on tumour progression and therapeutic outcomes. In this Review, we focus on the main chemokines that are found in the human tumour microenvironment; we elaborate on their patterns of expression, their regulation and their roles in immune cell recruitment and in cancer and stromal cell biology, and we consider how they affect cancer immunity and tumorigenesis. We also discuss the potential of targeting chemokine networks, in combination with other immunotherapies, for the treatment of cancer.

Chemokines are small, secreted proteins that are best known for their roles in mediating immune cell trafficking and lymphoid tissue development1,2. The chemokines are the largest subfamily of cytokines and can be further subdivided into four main classes depending on the location of the first two cysteine (C) residues in their protein sequence: namely, the CC-chemokines, the CXC-chemokines, C-chemokines and CX3C-chemokines2. There is an important degree of redundancy in the chemokine superfamily, with many ligands binding different receptors and vice versa2 (FIG. 1). In the tumour microenvironment, chemokines can be expressed by tumour cells and other cells, including immune cells and stromal cells. In response to specific chemokines, different immune cell subsets migrate into the tumour microenvironment and regulate tumour immune responses in a spatiotemporal manner. In addition, chemokines can directly target non-immune cells — including tumour cells and vascular endothelial cells — in the tumour microenvironment, and they have been shown to regulate tumour cell proliferation, cancer stem-like cell properties, cancer invasiveness and meta stasis. Therefore, chemokines directly and indirectly affect tumour immunity; shape tumour immune and biological phenotypes; and influence cancer progression, therapy and patient outcomes3–10 (FIG. 1). In this Review, we describe the expression patterns and regulation of the main chemokines that are found in the human cancer microenvironment, and their effects on immune cells and non-immune cells. There has recently been a huge amount of research on cancer immunology and immunotherapy10,11, and here we discuss whether selectively targeting chemokine–chemokine receptor signalling could complement and increase the efficacy of the immunotherapies that are currently being used in cancer treatment3,4,10,12.

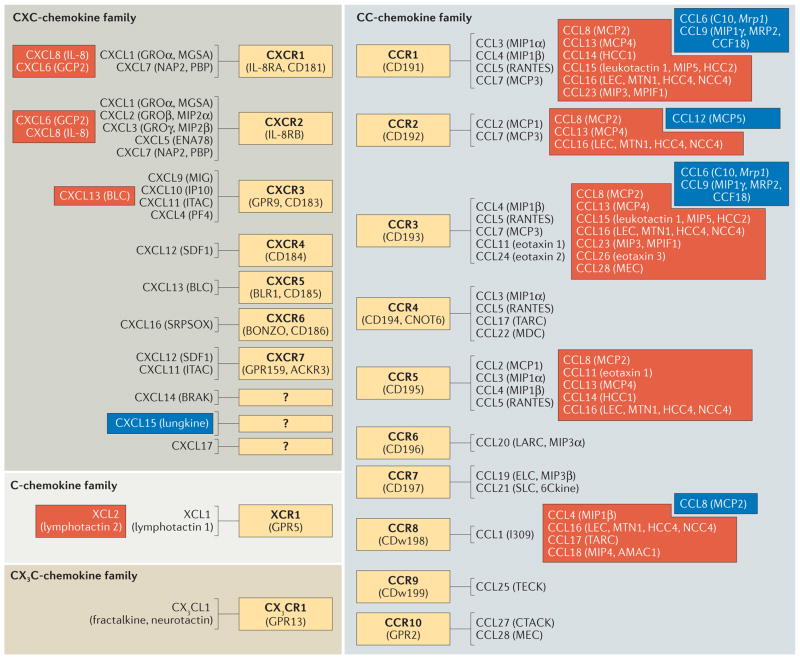

Figure 1. Chemokine receptor and ligand pairings.

The chemokine receptors and ligands that belong to each of the main chemokine families (namely, the C-, CC-, CXC- and CX3C-chemokine families) are shown. Blue and red boxes represent chemokine–chemokine receptor interactions that occur in mice and humans, respectively, and the non-boxed interactions occur in both humans and mice. Abbreviations enclosed in parentheses indicate alternative names for the preceding chemokine or chemokine receptor. Question marks indicate that the respective chemokine receptor is currently unknown.

Immune cell tumour trafficking

Different lymphocytes traffic into the tumour microenvironment, and they can modulate tumour immune responses in both primary tumours and metastatic sites. Here, we discuss several key chemokine networks that regulate lymphocyte recruitment into the tumour microenvironment, and discuss how the recruited lymphocyte subsets regulate tumour immunity and tumorigenesis.

The recruitment of effector T cells and natural killer cells

CD8+ T cells that are specific for tumour-associated antigens (TAAs) can engage tumour cells in an antigen-specific manner, and they drive antitumour immunity by secreting effector cytokines, releasing cytotoxic molecules (such as granzyme B and perforin) and inducing apoptosis in tumour cells. In addition to CD8+ T cells, interferon-γ (IFNγ)-expressing T helper 1 (TH1) cells and natural killer (NK) cells have potent antitumour effects in the tumour microenvironment. Effector CD8+ T cells, TH1 cells and NK cells express CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3), which is the receptor for the TH1-type chemokines CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXCL10, and they can migrate into tumours in response to these chemokines (FIG. 2). Increased levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10 are associated with increased numbers of tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, and correlate with decreased levels of cancer metastasis and improved survival in patients with ovarian cancer and colon cancer13–18. Recent studies have demonstrated that tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and intratumoural TH1-type chemokines are associated with positive responses to therapeutic blockade of the immune checkpoint molecules programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) and PD1 ligand 1 (PDL1; also known as B7-H1)10. Interestingly, CD8+ T cells in the tumour microenvironment were shown recently to regulate the metabolism of the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin by fibroblasts in ovarian cancer19. In this study, CD8+ T cell-derived IFNγ altered glutathione and cysteine metabolism in fibroblasts, and abolished their resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy19, suggesting that CD8+ T cells can also affect tumour cell fate in a TAA-independent manner. Therefore, TH1-type chemokines can recruit effector immune cells into the tumour microenvironment, and these immune cells can subsequently shape tumour immunity and therapeutic responses through both TAA-specific and TAA-independent mechanisms.

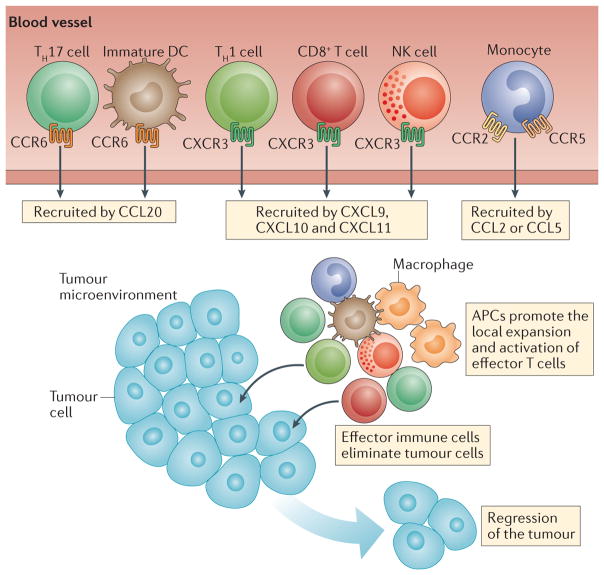

Figure 2. The promotion of tumour immunity by chemokines.

Immune cells with antitumour effects — such as CD8+ T cells, T helper 1 (TH1) cells, polyfunctional TH17 cells and natural killer (NK) cells — are recruited to the tumour microenvironment through chemokine–chemokine receptor signalling pathways. CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) and its ligands CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXCL10 have a key role in driving the trafficking of TH1 cells, CD8+ T cells and NK cells into the tumour microenvironment, whereas CC-chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20) signalling through CC-chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6) promotes the recruitment of TH17 cells. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages and dendritic cells are also recruited into the tumour microenvironment, and they can activate and expand the local effector immune cells, thereby promoting tumour regression.

The recruitment of TH17 cells

Human TH17 cells express high levels of CC-chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6), CXCR4, multiple CD49 integrins and the C-type lectin-like receptor CD161 (REFS 17,20–22). These homing molecules may be associated with TH17 cell migration and retention within inflammatory tissues and tumours17,21,23,24. For example, high levels of CXCL12 (also known as SDF1; the ligand for CXCR4)25,26 and CC-chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20; the ligand for CCR6)27 are found in human tumour microenvironments. This chemokine profile may facilitate the trafficking of TH17 cells into tumours. TH17 cells do not express CD62 ligand (CD62L; also known as L-selectin) or CCR7 (REF. 17), which promote lymphocyte homing to lymph nodes, and this suggests that their potential to home to lymphoid tissues is limited. In both humans and mice, tumour- infiltrating TH17 cells are polyfunctional17,22,28, have stem-like properties and mediate potent antitumour immunity8,17,22,24,28. TH17 cells do not secrete cytotoxic molecules such as granzyme B and perforin, but instead mediate antitumour activity by recruiting CD8+ T cells17,22, NK cells29 and dendritic cells (DCs)24 into the tumour microenvironment. Of note, interleukin-17 (IL-17) has been shown to target the tumour stroma and also to promote tumour angiogenesis in mouse models, an effect that may promote tumour growth8. Nevertheless, the chemokine-driven recruitment of polyfunctional TH17 cells into the tumour micro environment may be beneficial for patients with cancer8.

The recruitment of TH22 cells

TH22 cells are found in the microenvironment of several types of human cancer, including colon cancer, pancreatic cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma30–33. These cells express CCR6, migrate towards the CCR6 ligand CCL20 in the colon cancer microenvironment, and have been shown to promote and support tumorigenesis30. TH22 cell-derived IL-22 acts on cancer cells to promote the activation of the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), increase the expression of the histone H3 lysine 79 (H3K79) methyltransferase DOT1L30, and upregulate the expression of the H3K27 methyltransferase Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), particularly the enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) subunit34. The DOT1L complex induces the expression of the core stem cell genes NANOG, SOX2 (which encodes SRY-box 2) and POU5F1 (which encodes POU class 5 homeobox 1), resulting in increased cancer stemness and tumorigenic potential30, whereas increased expression of EZH2 has been shown to support the proliferation of colon cancer cells34. A pro-tumour role of IL-22 has been supported by studies in two mouse models of colon cancer. In a bacteria-induced colon cancer model, IL-22-expressing colonic innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) accumulate in the tumour tissues, and their depletion blocks the development of invasive colon cancer35. In a colon tumour model that is induced by azoxymethane and dextran sulfate sodium, the downregulation of IL-22-binding protein (IL-22BP) expression increases the ratio of IL-22 to IL-22BP and promotes tumorigenesis36. Thus, the recruitment of TH22 cells into the tumour microenvironment via the CCL20–CCR6 axis may promote tumorigenesis37.

The recruitment of regulatory cells

Another way in which chemokines may promote tumorigenesis is by mediating the recruitment of regulatory T (Treg) cells into the tumour microenvironment. Treg cells express CCR4 and are recruited into the tumour micro environment in response to CCL22, which is produced mainly by macrophages and tumour cells38. Treg cells suppress spontaneous and therapy-induced T cell antitumour immunity, leading to tumour growth and poor patient outcomes5,38. In addition to the CCL22–CCR4 signalling pathway, Treg cells express CCR10 and migrate in response to the CCL28 that is found in hypoxic regions of the tumour microenvironment39.

The bone marrow is a common site of tumour metastasis in humans, suggesting that the bone marrow may provide an immunosuppressive microenvironment that supports tumour retention and growth40. In line with this notion, high frequencies of Treg cells are found in the bone marrow41. Bone marrow Treg cells exhibit a memory phenotype and express functional CXCR4 (REF. 41). Treg cells can be mobilized from the bone marrow into the periphery by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), which promotes the degradation of CXCL12 in the bone marrow41. High numbers of Treg cells in the bone marrow may provide an immune ‘shield’ that facilitates tumour metastasis to this site. This may explain why cancers often metastasize to the bone marrow6,42. In further support of this possibility, the numbers of Treg cells are further increased in the bone marrow of patients with prostate cancer who show bone metastasis42. These Treg cell populations are recruited into the bone marrow via the CXCL12–CXCR4 signalling pathway and are expanded by DCs via the receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK)–RANK ligand (RANKL) signalling pathway (also known as the TNFRSF11A–TNFSF11 signalling pathway)42.

Treg cells may express inflammatory cytokines — including CXCL8 (also known as IL-8)43 and IL-17 (REF. 44) — in the human colon cancer microenvironment. Interestingly, CXCL8+ and IL-17+ Treg cells not only mediate T cell suppression but also promote inflammation in the cancer microenvironment. Thus, the chemokine-mediated recruitment of Treg cells into the tumour microenvironment and their presence at pre-metastatic sites supports tumour initiation, progression and metastasis (FIG. 3).

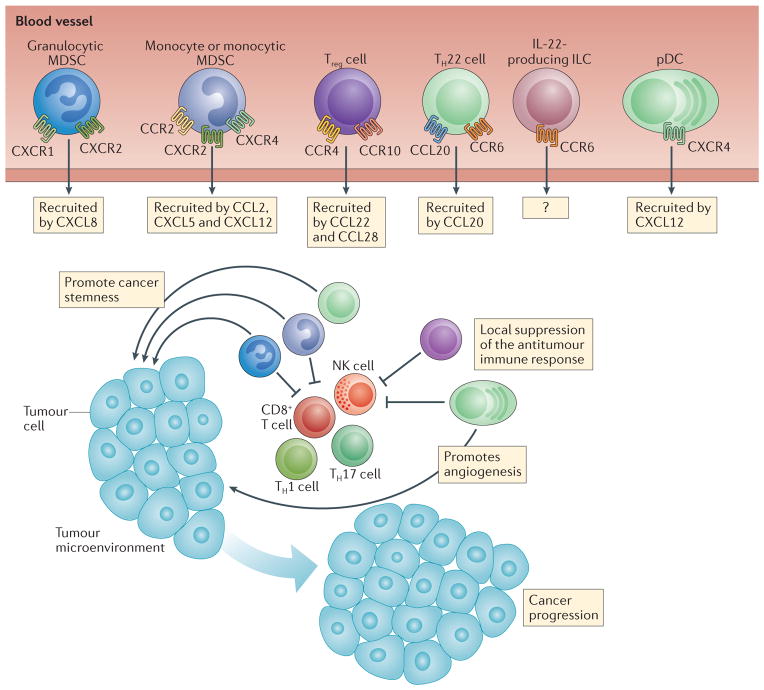

Figure 3. Pro-tumour effects of chemokines.

Immune cell populations such as granulocytic and monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), regulatory T (Treg) cells, IL-22+CD4+ T helper 22 (TH22) cells, IL-22+ innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) can promote tumour growth. These cells are recruited to the tumour microenvironment in response to different chemokines that are expressed in the tumour microenvironment (the relevant receptors and ligands are shown). Pro-tumour immune cells may inhibit antitumour immune responses, and may also promote and maintain cancer stemness and angiogenesis, leading to cancer progression. CCL, CC-chemokine ligand; CCR, CC-chemokine receptor; CXCL, CXC-chemokine ligand; CXCR, CXC-chemokine receptor.

The recruitment of NKT cells

Type I NKT cells, which are defined by their expression of an invariant T cell receptor (TCR) — namely, Vα14Jα18+ in mice and Vα24Jα18+ in humans — mainly have antitumour immune activities, as they produce IFNγ to activate NK cells and CD8+ T cells, and they activate DCs to produce IL-12 (REF. 45). By contrast, type II NKT cells, which are characterized by the expression of more diverse TCRs that recognize lipids presented by CD1d, primarily inhibit tumour immunity45. Most NKT cells express non-lymphoid-homing or inflammation- related chemokine receptors including CCR2, CCR5 and CXCR3 (REF. 46). CCL2 mediates the trafficking of type I NKT cells into neuroblastomas47,48. NKT cell trafficking into other types of tumour is poorly studied.

The recruitment of B cells

Human tumour-infiltrating B cells have been less well-studied than have effector T cells49. B cells express CXCR4 and may be recruited by CXCL12 into the cancer microenvironment. High levels of tumour-infiltrating B cells are associated with a survival advantage in breast cancer50, high-grade serous ovarian cancer51 and cervical cancer52. B cells may also be present in tumour-associated tertiary lymphoid structures53 and increase T cell responses by releasing cytokines and chemokines, by serving as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and by producing antibodies. However, mouse studies indicate that B cells may negatively regulate tumour immunity and promote tumour progression via IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) expression54–56. Furthermore, by activating Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) on myeloid cells and mast cells, B cells can promote tumour angiogenesis and the recruitment of tumour-promoting immune cells54–56. There may be different subsets of B cells, including regulatory B cells57; however, it is unknown whether different B cell subsets are recruited into the tumour microenvironment by different chemokines, and whether they have differential roles in human tumour immunity and tumorigenesis.

In summary, different lymphocyte subsets are recruited into the tumour microenvironment by distinct chemokine–chemokine receptor signalling pathways. Effector T cells, NK cells and perhaps NKT cells may mediate an antitumour immunity, whereas Treg cells, TH22 cells and perhaps B cells may promote tumorigenesis.

Chemokines and tumour-associated APCs

APCs — including DCs, macrophages, B cells (discussed above) and perhaps myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) — are recruited into the tumour microenvironment; they regulate antitumour immunity by interacting with T cells, and affect tumorigenesis by interacting with tumour (stem-like) cells and stromal cells.

The recruitment of myeloid DCs to tumours

Mature myeloid DCs can drive potent antitumour immune responses by priming and activating TAA-specific T cells58. By contrast, immature myeloid DCs are poor mediators of T cell activation and can induce TH2-type immune responses27,59, which may support tumour progression. Immature myeloid DCs, but not mature myeloid DCs, are found in breast cancer and the cancer stroma27,60. Immature DCs express CCR6 and are recruited into tumours in response to tumour-derived CCL20 (REFS 27,60). However, in experimental mouse models, the overexpression of CCL20 (REF. 61) and CXCL14 (REF. 62) can attract myeloid DCs to the tumour, and promote DC maturation and inhibit tumour growth. The trafficking patterns of myeloid DCs in other types of human cancer are poorly defined.

The recruitment of plasmacytoid DCs

Plasmacytoid DCs are found in the human tumour microenvironment. Tumour and stromal cells produce CXCL12 (REFS 25,26,63), and plasmacytoid DCs express integrin α5 (also known as VLA5) and CXCR4, which are the key molecules that mediate plasmacytoid DC trafficking to tumours25. CXCL12 also protects plasmacytoid DCs in tumours from undergoing apoptosis26. In vitro studies have shown that plasmacytoid DCs isolated from human tumour tissues can respond to viral infection by producing high levels of type I IFN25. However, plasmacytoid DCs can also induce the development of IL-10-producing regulatory CD8+ T cells that suppress the ability of myeloid DCs to activate TAA-specific effector T cells25,64. Furthermore, these regulatory CD8+ T cells express CCR7, and may home to the draining lymph nodes and suppress TAA-specific T cell priming64. In addition, plasmacytoid DCs can promote tumour angiogenesis65. Thus, the recruitment of plasma cytoid DCs into the human tumour micro environment by CXCL12 may support the development of an immunosuppressive site that is permissive for tumour progression.

The recruitment of macrophages

Macrophages can be recruited into the tumour microenvironment by CCL2–CCR2 signalling66. CCL2 expression by tumours correlates with the numbers of tumour-associated macro phages (TAMs) in many tumours and is associated with poor patient prognosis in some cancers, including breast cancer67. TAMs may inhibit TAA-specific T cell activation via the expression of inhibitory B7 family members, including PDL1 and B7-H4 (also known as VTCN1), and through the induction of the galectin 9–T cell immunoglobulin mucin 3 (TIM3) pathway68–71. Furthermore, TAMs support chemo resistance72, and promote cancer stemness and meta stasis67,73. CCL2 can also activate metastasis-associated macrophages to secrete CCL3, which further promotes macrophage retention in the tumour and tumour meta static sites74. The CCL5–CCR5 pathway may be an additional chemo attractant signalling axis that affects macrophages in breast cancer. Increased CCL5 expression correlates with more advanced stages of breast cancer75,76. Thus, the recruitment of macrophages into the tumour micro environment may promote tumour progression. However, different subsets of macrophages77 and macrophages in different maturation stages may have diverse functions in tumours71,78,79. For example, CD68+ macrophages are associated with improved survival among patients with colon cancer79. CD169+ macro phages can mediate TAA-specific T cell cross-priming in tumour-draining lymph nodes, and initiate and promote tumour immunity in a mouse model80. Furthermore, macrophages can either increase or antagonize the antitumour efficacy of cytotoxic chemotherapy, cancer-cell targeting antibodies and immunotherapeutic agents81. Thus, targeting macrophages by the manipulation of chemokine–chemokine receptor signalling as a therapeutic approach may need to take these effects into account.

The recruitment of MDSCs

MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of myeloid cells that includes monocytic and granulocytic cells82. Monocytic MDSCs are macrophages in different maturation stages. Granulocytic MDSCs are mostly neutrophils in different maturation stages. The immune-suppressive effects of MDSCs are relatively well-studied in mouse tumour models82–85 and in patients with cancer73,86–88. Interestingly, recent studies demonstrate that MDSCs endow cancer cells with stem cell-like properties and are linked with cancer stemness73,86–88. Monocytic MDSCs (macrophages) can be recruited into the tumour microenvironment by CCL2 (REFS 74,89). The CXCL5–CXCR2 and CXCL12–CXCR4 signalling pathways are also reported to be involved in MDSC trafficking in a breast tumour mouse model90. CXCL8 regulates granulocytic MDSC migration and degranulation via CXCR1 and CXCR2 signalling91. Tumour cells and myeloid cells express CXCL8, and recruit neutrophils into the tumour microenvironment91. Certain subsets of Treg cells in the human cancer microenvironment express CXCL8 and promote neutrophil migration into tumours43. Neutrophils secrete various molecules that support and promote tumour angiogenesis. Thus, the recruitment of neutrophils by CXCL8 is generally thought to promote tumour progression and metastasis91,92.

In summary, distinct chemokines mediate the recruitment of different APC subsets into the tumour microenvironment, and these APCs differentially regulate tumour immunity and cancer progression. In addition to targeting immune cells, chemokines can also affect tumorigenesis by directly targeting tumour cells and tumour stromal cells.

Effects of chemokines on tumour cells

Chemokines can directly and indirectly target tumour stem-like cells and stromal cells in tumours. Below, we discuss how different chemokine–chemokine receptor signalling pathways affect tumour cell proliferation, stemness and angiogenesis to ultimately alter tumour metastasis and disease outcomes in patients (TABLE 1).

Table 1.

Chemokine functions in the tumour microenvironment

| Chemokine | Effects on immune cell trafficking into the tumour or bone marrow | Direct effects on tumour cells | Indirect effects on tumour cells | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokines with pro-tumour roles | ||||

| CCL2 | Recruitment of monocytes, NKT cells and monocytic MDSCs | Promotes tumour cell proliferation, stemness and survival | Promotes tumour vascularization, and cancer extravasation and metastasis | 93–97,99,100 |

| CCL3 | Recruitment of monocytes and macrophages | ND | Promotes cancer extravasation | 97 |

| CCL5 | Recruitment of monocytes and macrophages | Drives metastasis | Promotes cancer invasion | 76,97,103 |

| CCL18 | ND | Promotes invasion and metastasis | ND | 105–109 |

| CCL25 | ND | Promotes chemoresistance, and tumour invasion and metastasis | ND | 116–120,122 |

| CXCL8 | Recruitment of neutrophils and granulocytic MDSCs | Promotes stemness, invasion and migration; apoptosis; resistance to hypoxia; and premature senescence | Promotes angiogenesis | 126–129,132–135 |

| CXCL12 | Recruitment of B cells and pDCs; and recruitment of Treg cells into the bone marrow | Promotes proliferation and survival; drives invasion and metastasis; and promotes stemness | Promotes angiogenesis | For CXCR4: 26,136,139–144,146 For CXCR7: 148,150,153,154 |

| CXCL14 | Recruitment of DCs | Promotes invasion and motility | ND | 190 |

| CXCL17 | Recruitment of granulocytic MDSCs | ND | Promotes angiogenesis | 163,164,216 |

| Chemokines with antitumour roles | ||||

| CXCL8 | Recruitment of neutrophils and granulocytic MDSCs | Increases the immunogenicity of the tumour | ND | 166 |

| CXCL9 and CXCL10 | Recruitment of T cells and NK cells | ND | Angiogenesis inhibitors | 169–171 |

| CXCL14 | Recruitment of DCs | Inhibits proliferation, invasion and metastasis; increases apoptosis | ND | 158,161,174 |

CCL, CC-chemokine ligand; CXCL, CXC-chemokine ligand; CXCR, CXC-chemokine receptor; DC, dendritic cell; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; ND, not defined; NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T; pDC, plasmacytoid DC; Treg cell, regulatory T cell.

Direct pro-tumour effects of chemokines

CCL2, CCL3 and CCL5 can promote tumour invasion and meta stasis. CCL2 targets vascular endothelial cells via the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)–STAT5 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways93, and affects tumour vas cularization94–96 and tumour metastasis93. CCL2, CCL3 and CCL5 can induce matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) secretion by monocytes76,97; MMP9, by degrading the matrix, allows for tumour cell extravasation98. Furthermore, CCL2 and CCL5 can promote cancer cell proliferation, survival, motility99, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and stemness100–103. In addition, these chemokines recruit MDSCs and macrophages into the tumour microenvironment, and in turn, promote and sustain human cancer stemness73,86,88,104.

CCL18 can directly influence tumour cells by, for example, promoting invasion, metastasis and EMT in breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer and prostate cancer105–109. However, the effect of CCL18 seems to depend on the cancer type, as high levels of CCL18 are a good prognostic factor in gastric cancer110. CCL18 inhibits cutaneous T cell proliferation111. In some cancers, such as breast cancer, the main source of CCL18 in the tumour is TAMs, whereas ovarian cancer cells can overexpress CCL18 (REFS 105,106). Although not shown in cancer, CCL18 has an immunosuppressive effect on DCs and macrophages112–115. CCL18-conditioned APCs may induce the differentiation of Treg cells, leading to immunosuppression. This CCL18-driven immunosuppression might exist in the tumour microenvironment112–115.

The receptor for CCL25, CCR9, is highly expressed in many cancers. CCR9 signalling in tumour cells increases their resistance to chemotherapy116,117 and their expression of MMPs, which promote cancer invasion and metastasis118–122. CCL25 can also promote metastasis by recruiting CCR9+ cancer cells into CCL25-expressing tissues, such as the small intestine. For example, cutaneous melanoma cells, and possibly adult lymphoblastic leukaemia cells, preferentially metastasize to the small intestine owing to signalling via the CCR9–CCL25 axis123–125.

CXCL8 targets vascular endothelial cells and regulates angiogenesis by promoting endothelial cell survival126. CXCL8 targets cancer cells; promotes cancer invasion and migration127; induces tumour premature senescence128; contributes to hypoxia-induced tumour apoptosis resistance129; and promotes EMT130 and cancer stemness131–135. Thus, CXCL8 signalling is important in cancer cell biology.

CXCL12 targets vascular endothelial cells and synergizes with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to promote tumour angiogenesis26,136. CXCL12 can also promote tumour cell proliferation and survival63,137. Furthermore, the CXCL12–CXCR4 signalling pathway promotes cancer cell invasion and metastasis138–143. It has been suggested that CXCR4+ tumour cells may have stem-like properties, have a high metastatic potential and show radiation resistance144– 146. Thus, the CXCL12–CXCR4 signalling pathway has a role in tumour proliferation, metastasis and stemness. CXCL12 can also bind to CXCR7 (REFS 147,148). Although considered a decoy and scavenger receptor147–149, CXCR7 can signal through non-G-protein-mediated mechanisms in cancer cells and endothelial cells, including tumour-associated endothelial cells150,151. Its role as a stand-alone G protein-coupled receptor is still under debate, but it can bind to CXCR4 and mediate signalling through intracellular CXCR4 signalling molecules, a process implicated in the chemotaxis of T cells147,152. As mentioned above, cancer cells express CXCR7, which can promote the adhesion, invasion, survival and growth of prostate cancer153,154, breast cancer148,150, and lung cancer cells150. CXCR7 signalling can also indirectly contribute to angiogenesis by increasing the expression of CXCL8 and VEGF in prostate cancer cells153.

CXCL14 (also known as BRAK) has been reported to be involved in tumorigenesis. Interestingly, the effect of CXCL14 in different cancers varies. Cancers such as those of pancreas155 and prostate156 show increased CXCL14 expression, whereas other types of cancer — including breast cancer, kidney cancer, cervical cancer, and head and neck cancer — consistently lose expression of CXCL14 (REFS 157–160). In line with this, the overexpression of CXCL14 in breast tumours that lack CXCL14 or even in tumour myoepithelial cells leads to reduced tumour growth, metastasis and invasion158,161. Even though the receptor for CXCL14 is still unknown, in vivo loss of CXCL14 is correlated with reduced DC loss in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma mouse model62.

CXCL17 is highly expressed in various cancer cells, recruits granulocytic MDSCs into the tumour, and increases tumour growth partially by increasing angiogenesis162,163. Indeed, CXCL17 induces VEGF expression in monocytes and endothelial cells163,164. As CXCL17 is highly expressed in many cancers, including colon cancer, it is likely to be an important chemokine for mucosal tumours and mucosal immunity165.

Direct antitumour effects of chemokines

Dying cancer cells can be immunogenic and can direct the antitumour immune response. CXCL8, for example, can increase the immunogenicity of dying cancer cells by translocating calreticulin to the cell surface166. Calreticulin exposure on the cell surface increases the immunogenicity of the cell, and thus promotes the phagocytosis of these cells and antitumour immune responses to the tumour167. CXCL9 and CXCL10 are endogenous tumour angiogenesis inhibitors168,169. CXCL10 prevents both CXCL8-induced and basic fibroblast growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro170,171.

Regulation of chemokine expression in tumours

Chemokine expression is regulated by cancer-intrinsic genetic and epigenetic mechanisms and by environmental cues in the tumour microenvironment.

Epigenetic and oncogenic regulation of chemokine expression

The role of oncogenic genetic and epigenetic pathways is extensively studied in cancer biology. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that in human ovarian cancer and colon cancer, the PRC2 complex, the H3K27me3 demethylase JMJD3 (also known as KDM6B) and DNA methylation repress the expression of TH1-type chemokines in tumours and prevent the trafficking of effector T cells into the tumour micro environment172,173. Pharmacological and genetic interventions that increase TH1-type chemokine production lead to increased effector T cell trafficking into tumours, and improve the therapeutic efficacy of PDL1 blockade and T cell transfusion in preclinical models172,173. CXCL14 expression is also reported to be repressed in lung cancer cells by DNA methylation, and forced expression of CXCL14 leads to reduced tumour growth174. Furthermore, human melanoma tissues that show little T cell infiltration display active β-catenin signalling175. In a genetically engineered mouse melanoma model, β-catenin activation results in poor expression of CCL4 — a chemokine that is essential for CD103+ DC migration — and subsequently limits DC-mediated effector T cell activation and expansion within the tumour175. Another epigenetic repressor, histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) can interact with the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) subunit p65 (also known as RELA) and repress CXCL8 expression176,177.

Genetic regulation, mainly mutations, can influence chemokine receptor expression and function. A point mutation has been identified in CXCR4 (G574A) in a melanoma cell line and a colon cancer cell line178. This mutation is functionally active, and the mutant receptor signals and traffics in response to CXCL12, but when tumours expressing this mutant receptor were allowed to grow in vivo, tumour growth was delayed178. Indirectly, a common gene fusion of PAX3 (which encodes paired box 3) and FKHR (which encodes forkhead homologue in rhabdomyosarcoma; also known as FOXO1) in rhabdomyosarcoma is associated with higher CXCR4 expression179. Transfer of this gene fusion leads to higher CXCR4 expression in embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma cells and increases invasion in vitro179. Both of these studies indicate the diverse roles of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Thus, tumour-intrinsic oncogenic175 and epigenetic172,173 pathways control chemokine expression, and influence immune cell activation in and/or migration into the tumour microenvironment.

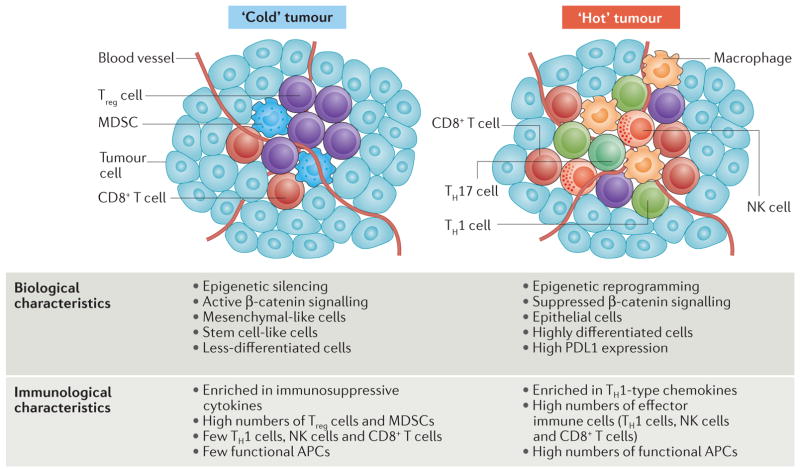

Both PRC2-mediated epigenetic silencing180 and β-catenin signalling are tumour-intrinsic tumorigenic mechanisms, and are associated with cancer EMT and a stem cell-like biological phenotype. Interestingly, these tumour-intrinsic mechanisms can regulate chemokine expression and control immune cell infiltration into tumours. Based on having either relatively high or low immune cell infiltration, tumours may be immunologically classified into ‘hot’ (inflamed) or ‘cold’ (non-inflamed) phenotypes, respectively. Thus, oncogenic genetic and epigenetic pathways simultaneously define the biological and immunological phenotypes of the tumour, affect tumour progression, and alter spontaneous and therapy-induced tumour-specific T cell immunity (FIG. 4). The manipulation of these tumour-intrinsic pathways may promote the infiltration of T cells into tumours, alter tumour immune phenotype and ultimately lead to tumour regression.

Figure 4. The relationship between, and mechanisms that underlie, tumour immune phenotype and biological phenotype.

Active tumour β-catenin signalling inhibits CC-chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4) expression, and limits CD103+ dendritic cell (DC) recruitment and CD8+ T cell activation and expansion. The expression of the genes encoding the T helper 1 (TH1)-type chemokines CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXCL10 is repressed by the histone-lysine N-methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2) and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT)-mediated epigenetic silencing. Consequently, CD8+ T cells poorly infiltrate the tumour, and the tumour is immunologically ‘cold’ (left). High levels of tumour β-catenin, EZH2 and DNMTs endow cancer stemness, which can be further promoted and maintained by pro-tumour immune cells. Thus, the immunologically cold tumour is biologically prone to have a more stem-like phenotype. Reversing this mechanism by epigenetic reprogramming and the suppression of β-catenin signalling may make the tumour immunologically ‘hot’ and promote the recruitment of effector immune cells with antitumour functions (including TH1 cells, natural killer (NK) cells, CD8+ T cells, polyfunctional TH17 cells and functional antigen-presenting cells (APCs)), thereby driving tumour regression. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; PDL1, programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1; Treg cell, regulatory T cell.

Hypoxia and chemokine expression in tumours

Hypoxia is a general phenomenon in the cancer microenvironment. The transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1; which comprises HIF1α and HIF1β) is the central mediator of the cellular response to hypoxia181. Hypoxia triggers CXCL12 expression in primary human ovarian tumour cells26, fibroblasts182 and haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)183. In the promoter region of the CXCL12 gene, there are two potential HIF1-binding sites (HBSs) termed HBS1 and HBS2 (REF. 183). The HBS1 region may be responsible for the HIF1-dependent induction of CXCL12 synthesis183. Hypoxia also promotes CXCR4 expression in TAMs and tumour cells184,185. In renal cell carcinoma, the mechanism of CXCR4 upregulation involves mutation of the tumour-suppressor gene VHL (which encodes von Hippel–Lindau protein)185. Increased CXCR4 expression and migration towards CXCL12 are dependent on HIF1α activation and CXCR4 transcript stabilization184,185. As well as inducing the expression of CXCR4 and CXCL12, hypoxia can induce CXCR7 expression in rhabdomyosarcoma cells186. In addition, CCL2 also has HBSs in its promoter, and hypoxia has been found to induce CCL2 expression in human astrocytes187 and CXCL8 expression in ovarian cancer cells188. Thus, hypoxia can affect tumour immunity and biology by regulating the expression of several chemokines and chemokine receptors.

Metabolic regulation of chemokine expression in the tumour microenvironment

Aerobic glycolysis is a feature of cancer cell metabolism. In aerobic glycolysis, cancer cells produce lactic acid, which activates NF-κB and induces CXCL8 expression in vascular endothelial cells, resulting in angiogenesis in breast and colon cancer189. In breast cancer cells, reactive oxygen species can upregulate CXCL14 expression through the transcription factor activator protein 1 (AP-1), thus increasing cell invasion and motility190. Hormones can also regulate chemokine expression. In breast cancer cells, oestrogen can upregulate the expression of CXCR4 and CXCL12 and downregulate that of CXCR7 (REF. 191). Further studies will determine how cancer metabolism affects the expression of different chemokines in the tumour microenvironment.

The microbiota and tumour chemokine expression

Different bacteria can negatively and positively influence tumour growth. The microbiota and its by- products can modulate the tumour immune response192,193. These bacteria can recruit specific immune cell subsets, thus shaping tumour growth. For example, Fusobacterium nucleatum accelerates intestinal tumours, in part by increasing the infiltration of myeloid cells that suppress T cell activity into the tumours194. The binding of short-chain fatty acids from microorganisms to G protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43) leads to inflammation resolution in mouse models. GPR43-deficient mice have high levels of inflammation and immune cell recruitment, and an exacerbated immune response195. Another bacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium that decreases in abundance in patients with Crohn’s disease196,197. Its metabolites block NF-κB activation and CXCL8 production196,197. Thus, although there is no direct evidence of microbiota-induced regulation of chemokine expression in tumours, the microbiota and its by-products are presumably involved in tumour immune responses in specific types of human cancers such as colon cancer.

Chemokines and cancer immunotherapy

Given that chemokines and their receptors have crucial roles in inflammatory human diseases, efforts have been made to target chemokine networks in patients with autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammation. Drugs that target CCR5 (namely, maraviroc) and CXCR4 (namely, plerixafor; also known as AMD3100 and marketed as Mozobil by Genzyme) have been approved for use in HIV infection and for the mobilization of HSCs for transplantation, respectively. However, the targeting of chemokines and chemokine receptors has so far failed to yield any viable anti-inflammatory drugs. As discussed above, the chemokines CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL8, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL12 are relatively well studied in human cancer. Below, we focus on the potential of targeting these chemokines and their receptors to promote antitumour immune responses in patients with cancer, and we discuss the possibility of combining chemokine-based therapies with current cancer immunotherapies.

CXCL9 and CXCL10

Poor tumour infiltration by T cells has been attributed to potent epigenetic silencing of the genes encoding the TH1-type chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 in tumours172,173. As discussed above, these chemokines promote the migration of effector T cells and NK cells into tumours. Studies have shown that improved therapeutic responses to cancer immunotherapy and chemotherapy are associated with increased levels of TH1-type chemokines and increased numbers of effector T cells in the tumour microenvironment10,198. Thus, cancer epigenetic reprogramming may remove the epigenetic repression of genes encoding TH1-type chemokines, thus promoting effector T cell trafficking into the tumour microenvironment and improving the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy. In support of this, treatment with cancer epigenetic re programming drugs — including EZH2 inhibitors, DZNep199, a selective inhibitor of EZH2 methyltransferase activity (GSK126)200 or a DNMT inhibitor (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) — increases tumour TH1-type chemokine production and T cell trafficking into tumours172,173, and augments the therapeutic effects of PDL1 blockade and T cell therapy in a preclinical model172. Furthermore, treatment with azacitidine upregulates the expression of IFN signature genes in several human cancer cell lines201,202. 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment increases the expression of the cancer and germline TAA NY-ESO-1 (also known as cancer/testis antigen 1) in human ovarian cancer cells203, and promotes chemokine expression and T cell tumour trafficking in a mouse ovarian cancer model198. Thus, epigenetic re-programming can de-repress the repressed TH1-type chemokine-encoding genes, and promote the expression of IFN signature genes and TAAs, and may thus promote T cell infiltration into tumours and ultimately potentiate PDL1 and PD1 blockade therapy172,173,198.

CXCL12 and CXCR4

CXCL12–CXCR4 signalling is implicated in immune cell tumour trafficking and tumour cell biology. CXCL12–CXCR4 signalling mediates plasmacytoid DC trafficking into tumours25 and Treg cell homing to the bone marrow microenvironment41,42, and is involved in tumour cell proliferation63, metastasis138 and tumour vascularization26. AMD3100 is a CXCR4 antagonist and has been used in human clinical trials for the treatment of HIV infection204. The blockade of CXCR4–CXCL12 signalling may reduce tumour angiogenesis, invasiveness and tumour-induced immunosuppression. Indeed, anti-CXCR4 and anti-CXCL12 antibodies each prevented metastasis, reduced tumour weight and prevented tumour extravasation in preclinical models138,205–208. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the administration of antagonists of CXCR4–CXCL12 signalling could be therapeutically beneficial in combination with current immunotherapies. A clinical trial is now underway to evaluate the safety of combinatorial immunotherapy with the CXCR4 peptide antagonist LY2510924 and the anti-PDL1 antibody durvalumab209.

CXCL8 and CXCR1

CXCL8–CXCR1 signalling is involved in tumour angiogenesis, tumour stemness and inflammatory immune cell trafficking into the tumour microenvironment91. Strategies that aim to interfere with this chemokine regulatory loop may represent a strategy for targeting the cancer microenvironment. Repertaxin (also known as reparixin) is a noncompetitive allosteric inhibitor of CXCR1 and CXCR2. Repertaxin was originally developed to block CXCL8 activity, and thus reduce tissue damage after myocardial infarction or stroke210. A phase I clinical trial has demonstrated that repertaxin is well tolerated in healthy volunteers211. Further clinical trials are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of repertaxin in combination with current immunotherapies in patients with cancer.

CCL2, CCL3 and CCL5

These chemokines are implicated in macrophage and neutrophil recruitment into the tumour microenvironment. CCL5 promotes ovarian cancer stem-like properties101,102. CCL2, CCL3 and CCL5 may bind to CCR1, CCR2, CCR3 and CCR5. Targeting these chemokine receptors may prevent the accumulation of immunosuppressive myeloid cell in tumours. Indeed, targeting CCL2, CCL3 or CCL5 signalling inhibits metastasis and angiogenesis in mouse models of breast cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer66,74,96,101. However, the cessation of CCL2 neutralization monotherapy leads to increased metastasis and rapid death in mouse models of breast cancer96. Thus, CCL2 blockade may need to be combined with other immunotherapies to increase the antitumour response and avoid the potential detrimental effect of single-chemokine blockade. For example, CCL2 blockade synergistically improves the cancer vaccine response in mouse models of lung cancer and mesothelioma212. Macrophage depletion increases the therapeutic efficacy of anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) and anti-PD1 antibodies in mouse pancreatic cancer models213. Given that different subsets of macrophages may be functionally different, clinical studies are needed to determine whether macrophage depletion can yield an antitumour response. Indeed, a phase II clinical trial has been conducted using MLN1202, an anti-CCR2 monoclonal antibody, in patients with cancer bone metastasis214. In addition, Chemocentryx recently initiated a phase Ib trial of a CCR2 antagonist (CCX872) in patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer215. These clinical studies will provide the most-needed information on the safety and potential therapeutic efficacy of CCR2 signalling blockade in patients with cancer.

Concluding remarks

Chemokines and chemokine receptors mediate immune cell trafficking into the tumour micro environment. Different immune cell subsets differentially contribute to cancer progression and therapy. The genes that encode TH1-type chemokines are repressed by epigenetic mechanisms in cancer, and this affects the numbers of antitumour effector immune cells that are present within tumours, determines the cancer immune phenotype, and shapes the therapeutic efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade, adoptive T cell therapy and conventional therapy10,172,173. By contrast, the chemokines associated with the tumour trafficking of myeloid cells, Treg cells and TH22 cells can directly and indirectly influence the biological phenotype of a tumour (for example, whether it is a stem/EMT-type or non-stem/EMT-type tumour)30,34,43,73,86. Thus, direct and indirect manipulation of chemokine–chemokine receptor signalling pathways may reshape the immune and biological phenotypes of a tumour in a manner that increases the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy. Of note, clinical trials of agents that directly target a single chemokine or chemokine receptor have not yielded impressive therapeutic efficacy in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as AIDS, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. One reason for this is that chemokines generally bind to multiple receptors. These ligands may then activate alternative receptors, abrogating the effect of the single antagonist or blocker. Furthermore, therapies that target specific chemokines or chemokine receptors can affect the trafficking of different immune cell subsets into tumours and alter the biological activities of non-immune cells in the tumour microenvironment. Hence, similarly to what is seen in chronic inflammatory diseases, a therapeutic strategy of directly targeting a single chemokine or chemokine receptor may not achieve a meaningful clinical response. Based on current findings and the above discussion, it is predicted that directly targeting both pro-tumour and antitumour chemokine– chemokine receptor signalling pathways10,172,173 in combination with other immunotherapies could achieve clinical benefits in patients with cancer. Further studies in preclinical models and patients are required to bring this combination approach into clinical application.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their former and current collaborators and trainees for their intellectual input and hard work. The work described in this Review was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH; F31CA189440) and the Herman and Dorothy Miller Award for Innovative Immunology Research to N.N.; NIH grants CA193136, CA190176, CA171306, CA152470, CA099985, CA156685, CA123088, CA133620, CA092562, CA100227 and CA211016 to W.Z.; and NIH grant R35 CA129765 to M.S.W. The Review focuses mainly on the human cancer immune microenvironment and cancer patient-oriented studies. Owing to the plethora of literature related to the topic described in this Review, the writing of a complete and extensive article is extremely challenging. The authors apologize in advance for any inadvertent omissions.

Glossary

- Cancer stem-like cell

A cell that can self-propagate, is less-differentiated and can give rise to other tumour cells. These properties enable these cells to be potentially key players in tumour initiation, metastasis, and treatment resistance and/or cancer relapse

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing interests: see Web version for details.

References

- 1.Rot A, von Andrian UH. Chemokines in innate and adaptive host defense: basic chemokinese grammar for immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:891–928. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:659–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. This is a comprehensive review of chemokines and chemokine receptors and their roles in tumour development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. This thorough review highlights tumour and immune interactions that create an immunosuppressive and tolerizing microenvironment, and describes how their manipulation can influence therapeutic outcomes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei S, Kryczek I, Zou W. Regulatory T-cell compartmentalization and trafficking. Blood. 2006;108:426–431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nri2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou W, Restifo NP. TH17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:248–256. doi: 10.1038/nri2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crespo J, Sun H, Welling TH, Tian Z, Zou W. T cell anergy, exhaustion, senescence, and stemness in the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv324. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118. This is a recent review on PD1 and PDL1 that describes checkpoint blockade mechanisms, manipulation of PD1–PDL1 signalling and the influence of checkpoint blockade on therapeutic outcomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homey B, Muller A, Zlotnik A. Chemokines: agents for the immunotherapy of cancer? Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. This key paper shows that the infiltration of CD3+ T cells in ovarian cancer improves clinical outcome and positively associates with the intratumoural expression of IFNγ, IL-2 and chemokines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pages F, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. Reference 14 demonstrates that the infiltration of effector memory T cells in colon cancer correlates with a lack of metastasis and prolonged survival. References 13 and 14 highlight the importance of T cell infiltration in improving clinical outcome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato E, et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18538–18543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galon J, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kryczek I, et al. Phenotype, distribution, generation, and functional and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in the human tumor environments. Blood. 2009;114:1141–1149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao E, et al. Cancer mediates effector T cell dysfunction by targeting microRNAs and EZH2 via glycolysis restriction. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:95–103. doi: 10.1038/ni.3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W, et al. Effector T cells abrogate stroma-mediated chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cell. 2016;165:1092–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:639–646. doi: 10.1038/ni1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kryczek I, et al. Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-γ: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:4733–4741. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4733. This study shows how TH1 cell-derived IFNγ can induce human IL-17+ T cells to migrate into an inflammatory microenvironment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kryczek I, et al. Human TH17 cells are long-lived effector memory cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:104ra100. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muranski P, et al. Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood. 2008;112:362–373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-Orozco N, et al. T helper 17 cells promote cytotoxic T cell activation in tumor immunity. Immunity. 2009;31:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou W, et al. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1339–1346. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1339. Using an ovarian cancer model, the authors of this paper show that cancer-derived CXCL12 directly recruits plasmacytoid DC precursor cells and that tumour-associated plasmacytoid DCs weaken immunity by inducing the development of IL-10+ T cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kryczek I, et al. CXCL12 and vascular endothelial growth factor synergistically induce neoangiogenesis in human ovarian cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:465–472. This paper describes a novel angiogenesis strategy in which hypoxia-induced VEGF and CXCL12 production in ovarian cancer cells synergistically induces angiogenesis and vascular endothelial cell survival. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell D, et al. In breast carcinoma tissue, immature dendritic cells reside within the tumor, whereas mature dendritic cells are located in peritumoral areas. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1417–1426. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1417. This study demonstrates that the intratumoural and peritumoural localization of immature myeloid DCs is mediated by the CCL20–CCR6 chemokine axis in breast cancer tissue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Zou W. Th17 cells have stem cell-like features and promote long-term tumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:516–519. doi: 10.4161/onci.19440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kryczek I, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Zou W. Endogenous IL-17 contributes to reduced tumor growth and metastasis. Blood. 2009;114:357–359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kryczek I, et al. IL-22+CD4+ T cells promote colorectal cancer stemness via STAT3 transcription factor activation and induction of the methyltransferase DOT1L. Immunity. 2014;40:772–784. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.010. This study reveals the pro-tumour roles of TH22 cells in the tumour microenvironment. These cells traffic into the colon tumour microenvironment via CCR6–CCL20 signalling, and directly increase cancer stemness via IL-22 secretion and DOT1L-mediated epigenetic mechanisms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang YH, Cao YF, Jiang ZY, Zhang S, Gao F. Th22 cell accumulation is associated with colorectal cancer development. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4216–4224. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuang Y, et al. Increased intratumoral IL-22-producing CD4+ T cells and Th22 cells correlate with gastric cancer progression and predict poor patient survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1965–1975. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuang DM, et al. B7-H1-expressing antigen-presenting cells mediate polarization of protumorigenic Th22 subsets. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4657–4667. doi: 10.1172/JCI74381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun D, et al. Th22 cells control colon tumorigenesis through STAT3 and Polycomb repression complex 2 signaling. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1082704. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1082704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirchberger S, et al. Innate lymphoid cells sustain colon cancer through production of interleukin-22 in a mouse model. J Exp Med. 2013;210:917–931. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber S, et al. IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature. 2012;491:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature11535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perusina Lanfranca M, Lin Y, Fang J, Zou W, Frankel T. Biological and pathological activities of interleukin-22. J Mol Med (Berl ) 2016;94:523–534. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1391-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curiel TJ, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Facciabene A, et al. Tumour hypoxia promotes tolerance and angiogenesis via CCL28 and Treg cells. Nature. 2011;475:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao E, et al. Bone marrow and the control of immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:11–19. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou L, et al. Bone marrow is a reservoir for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells that traffic through CXCL12/CXCR4 signals. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8451–8455. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1987. This study helps to explain why cancers metastasize to the bone marrow. It shows that Treg cells traffic into the bone marrow via CXCR4-mediated signalling and create an immunosuppressive microenvironment that supports tumour metastasis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao E, et al. Regulatory T cells in the bone marrow microenvironment in patients with prostate cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:152–161. doi: 10.4161/onci.1.2.18480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kryczek I, et al. Inflammatory regulatory T cells in the microenvironments of ulcerative colitis and colon carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1105430. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1105430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kryczek I, et al. IL-17+ regulatory T cells in the microenvironments of chronic inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2011;186:4388–4395. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. NKT cells in tumor immunity: opposing subsets define a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. :180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim CH, Johnston B, Butcher EC. Trafficking machinery of NKT cells: shared and differential chemokine receptor expression among Vα24+Vβ11+ NKT cell subsets with distinct cytokine-producing capacity. Blood. 2002;100:11–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0196. This paper defines the differential chemokine receptor expression of different NKT cell subsets that facilitates their migration into inflammatory tissues. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metelitsa LS, et al. Natural killer T cells infiltrate neuroblastomas expressing the chemokine CCL2. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1213–1221. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031462. This is one of the few papers showing how NKT cells can migrate into tumours in response to CCL2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song L, et al. Oncogene MYCN regulates localization of NKT cells to the site of disease in neuroblastoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2702–2712. doi: 10.1172/JCI30751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson BH. CD20+ B cells: the other tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2010;185:4977–4982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt M, et al. The humoral immune system has a key prognostic impact in node-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5405–5413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milne K, et al. Systematic analysis of immune infiltrates in high-grade serous ovarian cancer reveals CD20, FoxP3 and TIA-1 as positive prognostic factors. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nedergaard BS, Ladekarl M, Nyengaard JR, Nielsen K. A comparative study of the cellular immune response in patients with stage IB cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Low numbers of several immune cell subtypes are strongly associated with relapse of disease within 5 years. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Germain C, Gnjatic S, Dieu-Nosjean MC. Tertiary lymphoid structure-associated B cells are key players in anti-tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2015;6:67. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreu P, et al. FcRγ activation regulates inflammation-associated squamous carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang C, et al. B cells promote tumor progression via STAT3 regulated-angiogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Affara NI, et al. B cells regulate macrophage phenotype and response to chemotherapy in squamous carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mizoguchi A, Bhan AK. A case for regulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:705–710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedroza-Gonzalez A, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin fosters human breast tumor growth by promoting type 2 inflammation. J Exp Med. 2011;208:479–490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aspord C, et al. Breast cancer instructs dendritic cells to prime interleukin 13-secreting CD4+ T cells that facilitate tumor development. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1037–1047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fushimi T, Kojima A, Moore MA, Crystal RG. Macrophage inflammatory protein 3α transgene attracts dendritic cells to established murine tumors and suppresses tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1383–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI7548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shurin GV, et al. Loss of new chemokine CXCL14 in tumor tissue is associated with low infiltration by dendritic cells (DC), while restoration of human CXCL14 expression in tumor cells causes attraction of DC both in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:5490–5498. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5490. References 61 and 62 highlight the importance of CXCL14 and CCL20 in myeloid DC migration into and activation within tumours. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scotton CJ, Wilson JL, Milliken D, Stamp G, Balkwill FR. Epithelial cancer cell migration: a role for chemokine receptors? Cancer Res. 2001;61:4961–4965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wei S, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce CD8+ regulatory T cells in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5020–5026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Curiel TJ, et al. Dendritic cell subsets differentially regulate angiogenesis in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5535–5538. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qian BZ, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. This paper shows that inhibition of the CCL2–CCR2 axis reduces macrophage recruitment and tumour metastasis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kryczek I, et al. B7-H4 expression identifies a novel suppressive macrophage population in human ovarian carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2006;203:871–881. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu K, Kryczek I, Chen L, Zou W, Welling TH. Kupffer cell suppression of CD8+ T cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by B7-H1/programmed death-1 interactions. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8067–8075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li H, et al. Tim-3/galectin-9 signaling pathway mediates T-cell dysfunction and predicts poor prognosis in patients with hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:1342–1351. doi: 10.1002/hep.25777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuang DM, et al. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma foster immune privilege and disease progression through PD-L1. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1327–1337. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Denardo DG, et al. Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:54–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wan S, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393–1404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kitamura T, et al. CCL2-induced chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1043–1059. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141836. This study demonstrates the importance of CCL2 signalling in macrophage tumour biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luboshits G, et al. Elevated expression of the CC chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) in advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4681–4687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Azenshtein E, et al. The CC chemokine RANTES in breast carcinoma progression: regulation of expression and potential mechanisms of promalignant activity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1093–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Edin S, et al. The distribution of macrophages with a M1 or M2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kuang DM, et al. Tumor-activated monocytes promote expansion of IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Immunol. 2010;185:1544–1549. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Forssell J, et al. High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1472–1479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2073. This paper reveals that CD68+ macrophage infiltration is positively associated with a better clinical outcome, and that the pro-tumorigenic and antitumorigenic roles of macrophages may depend on cancer cell–macrophage subset contact. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Asano K, et al. CD169-positive macrophages dominate antitumor immunity by crosspresenting dead cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2011;34:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriguez PC, et al. Arginase I in myeloid suppressor cells is induced by COX-2 in lung carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2005;202:931–939. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang B, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marigo I, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPβ transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cui TX, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhance stemness of cancer cells by inducing microRNA101 and suppressing the corepressor CtBP2. Immunity. 2013;39:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Panni RZ, et al. Tumor-induced STAT3 activation in monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhances stemness and mesenchymal properties in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:513–528. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1527-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peng D, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells endow stem-like qualities to breast cancer cells through IL6/STAT3 and NO/NOTCH cross-talk signaling. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3156–3165. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang L, et al. Abrogation of TGFβ signaling in mammary carcinomas recruits Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells that promote metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Waugh DJJ, Wilson C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6735–6741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Larco JE, Wuertz BRK, Furcht LT. The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4895–4900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wolf MJ, et al. Endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells enables extravasation via the JAK2–Stat5 and p38MAPK pathway. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.023. This study demonstrates the pro-tumour role of tumour-derived CCL2 on endothelial cell permeability and thus metastasis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goede V, Brogelli L, Ziche M, Augustin HG. Induction of inflammatory angiogenesis by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:765–770. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<765::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saji H, et al. Significant correlation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression with neovascularization and progression of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:1085–1091. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1085::aid-cncr1424>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonapace L, et al. Cessation of CCL2 inhibition accelerates breast cancer metastasis by promoting angiogenesis. Nature. 2014;515:130–133. doi: 10.1038/nature13862. This thought-provoking study emphasizes the detrimental effects of therapy targeting a single chemokine. Even though CCL2 neutralization reduces metastasis by reducing macrophage infiltration, the cessation of this blockade leads to rapid metastasis and increased monocyte infiltration into the metastatic tumour. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Robinson SC, Scott KA, Balkwill FR. Chemokine stimulation of monocyte matrix metalloproteinase-9 requires endogenous TNF-α. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:404–412. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<404::AID-IMMU404>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stamenkovic I. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:415–433. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fang WB, et al. CCL2/CCR2 chemokine signaling coordinates survival and motility of breast cancer cells through Smad3 protein- and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36593–36608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsuyada A, et al. CCL2 mediates cross-talk between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts that regulates breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2768–2779. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Long H, et al. Autocrine CCL5 signaling promotes invasion and migration of CD133+ ovarian cancer stem-like cells via NF-κB-mediated MMP-9 upregulation. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2309–2319. doi: 10.1002/stem.1194. This paper highlights the importance of CCL5 in increasing the invasiveness and migration of ovarian cancer stem-like cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zou W, Wicha MS. Chemokines and cellular plasticity of ovarian cancer stem cells. Oncoscience. 2015;2:615–616. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Long H, et al. CD133+ ovarian cancer stem-like cells promote non-stem cancer cell metastasis via CCL5 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5846–5859. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lu H, et al. A breast cancer stem cell niche supported by juxtacrine signalling from monocytes and macrophages. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:1105–1117. doi: 10.1038/ncb3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen J, et al. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang Q, et al. CCL18 from tumor-cells promotes epithelial ovarian cancer metastasis via mTOR signaling pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:1688–1699. doi: 10.1002/mc.22419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin L, et al. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes angiogenesis in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:34758–34773. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meng F, et al. CCL18 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion and migration of pancreatic cancer cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:1109–1120. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chen G, et al. CC chemokine ligand 18 correlates with malignant progression of prostate cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:230183. doi: 10.1155/2014/230183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Leung SY, et al. Expression profiling identifies chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 as an independent prognostic indicator in gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:457–469. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gunther C, et al. Up-regulation of the chemokine CCL18 by macrophages is a potential immunomodulatory pathway in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1434–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vulcano M, et al. Unique regulation of CCL18 production by maturing dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3843–3849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schutyser E, Richmond A, Van Damme J. Involvement of CC chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18) in normal and pathological processes. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:14–26. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Azzaoui I, et al. CCL18 differentiates dendritic cells in tolerogenic cells able to prime regulatory T cells in healthy subjects. Blood. 2011;118:3549–3558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338780. This study is one of the first to define a non-chemotactic effect of CCL18 on DCs; CCL18 promotes the differentiation of tolerogenic DCs, and this immunosuppressive effect may occur within tumours. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schraufstatter IU, Zhao M, Khaldoyanidi SK, Discipio RG. The chemokine CCL18 causes maturation of cultured monocytes to macrophages in the M2 spectrum. Immunology. 2012;135:287–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sharma PK, et al. CCR9 mediates PI3K/AKT-dependent antiapoptotic signals in prostate cancer cells and inhibition of CCR9–CCL25 interaction enhances the cytotoxic effects of etoposide. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2020–2030. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Johnson EL, et al. CCR9 interactions support ovarian cancer cell survival and resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis in a PI3K-dependent and FAK-independent fashion. J Ovarian Res. 2010;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]