Abstract

Approximately 25% of patients with ovarian cancer harbor a pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutation that has been associated with favorable responses for targeted therapy with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) inhibitors compared to wild-type individuals. The overall frequency of germline and somatic BRCA1/2 alterations is estimated at 13-15% and 3-10%, respectively. A high incidence of BRCA1/2 somatic variants significantly increases the number of patients eligible for treatment with PARP1 inhibitors. Here, we assessed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from 121 patients with ovarian cancer for BRCA1/2 mutational analysis by next generation sequencing. A total number of patients carrying the pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants was 30/121 (24.8%), including 22 and 7 individuals with exclusively germline or somatic mutations, respectively and one patient with variants of both origin. Among this cohort, more than one known pathogenic BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 alterations were identified in 7/30 individuals. The most recurrent mutations were detected in the BRCA1 gene: c.5266dupC (p.Gln1756Profs*74) with the frequency of ~18%, followed by c.3756_3759del (p.Ser1253Argfs*10) and c.181T>G (p.Cys61Gly). In seven (5.8%) patients, coincidence of two or more BRCA1/2 pathogenic mutations have been identified. Our results clearly demonstrate that the detection of both germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in ctDNA from ovarian cancer patients is feasible and may be a valuable complementary tool for identification of somatic alterations when the standard diagnostic procedures are insufficient. Finally, ctDNA can potentially allow to monitor the efficacy of PARP1 inhibitors and to detect a secondary reversion BRCA1/2 mutations.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, ctDNA, BRCA1/2, PARP1 inhibitor, next-generation sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common neoplasms among the European women, with more than 60,000 new cases diagnosed annually [1]. Approximately 13-15% of both unselected and familial ovarian cancer appear to be due to germline BRCA1/2 mutations [2, 3], while somatic alterations were found in the additional 3-10% of cases [4–8]. In total, about one-fifth of ovarian cancer patients carry a pathogenic variant in the BRCA1/2 gene. This worldwide frequency is comparable to the overall prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations among ovarian cancer patients in Polish population, estimating at ~15% for germline [9] and ~4% for somatic [10] variants.

A promising therapy with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) inhibitors has recently been widely studied in ovarian cancer patients [11, 12]. It has been demonstrated in clinical trials that BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are eligible for this targeted therapy by having a better response compared with wild-type individuals [13–15]. Therefore, identification of somatic mutations in the BRCA1/2 gene could expand the number of patients that may eventually benefit from treatment with PARP1 inhibitors.

The emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the approach to diagnostic procedures in personalized medicine. Recently, this method has been successfully implemented as a highly sensitive and cost-effective diagnostic tool to detect either germline or somatic mutations, even in degraded DNA such as from formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) material. However, due to the wide heterogeneity of tumor cells, low quality of the extracted DNA and its potential contamination with DNA from non-neoplastic cells, the analysis of FFPE tumor material can be challenging. Thus, there is a clear clinical need to develop rapid, cost-effective and non-invasive tools for mutation screening in cancer and consequently implement them as standard diagnostic procedures.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), initially reported in 1948 by Mandel and Metais [16], is defined as a fraction of fragmented DNA derived directly from the tumor and circulated in the patient's blood. Briefly, ctDNA that is obtained in so-called “liquid biopsy” provides the representative information of all subclones in a tumor, including the presence of gene alterations. Recently, numerous studies have investigated the clinical value of liquid biopsy as potential diagnostic material. However, almost none of the research referred to the detection of BRCA1/2 mutations in the plasma from ovarian cancer patients. To date, only Christie et al. (2017) reported the potential clinical utility of ctDNA analysis in 30 individuals with high-grade serous ovarian cancer [17]. However, this study aimed on the identification of reversion BRCA1/2 mutations that could be responsible for acquiring the chemotherapy resistance, not on the overall screening of both germline and somatic alterations in a large cohort of unselected ovarian cancer patients.

Here, for the first time we established the frequency of the germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in 121 ctDNA samples from unselected ovarian cancer patients by using the comprehensive mutational analysis with NGS. Our results clearly indicate the potential clinical utility of ctDNA in the diagnosis of the ovarian cancer patients. Proposed approach allows to identify simultaneously germline and somatic variants and results in the increased number of patients who are potentially eligible for PARP1 inhibitors treatment. In addition, we discussed the technical aspects of ctDNA analysis that hamper its clinical implementation in personalized oncology.

RESULTS

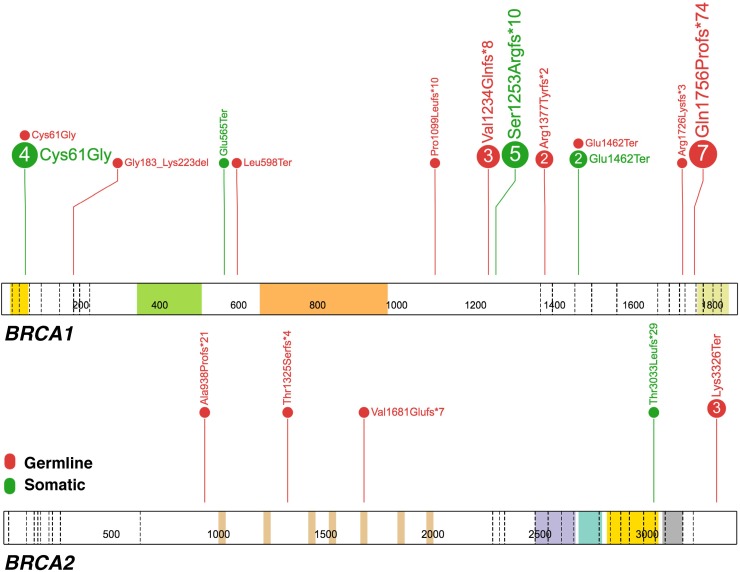

Initially, 134 patients were enrolled to the study. ctDNA extraction was successful for 131 (98%) samples, while mutational analysis could be performed for 121 (90%) individuals. In this cohort, the pathogenic germline and somatic variants were identified in 23 (19%) and 8 (6.6%) patients, respectively. In the current study, we confirmed presence of all germline mutations that were identified in our previous study [9]. A total number of the positive BRCA1/2 variants was 38, including 25 germline and 13 somatic alterations. In seven (5.8%) patients, coincidence of more than one pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations has been observed. Two individuals (#78 and #92) were classified as a double BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations carrier, one patient (#8) had both germline and somatic BRCA1/2 variants and in the remaining four patients we reported two (#169, #170, #171) or three (#175) different somatic BRCA1 alterations. In total, the BRCA1/2 mutations, either germline and/or somatic were detected in 30/121 (24.8%) individuals, including one patient carrying variants of both origin. The most recurrent alteration was c.5266dupC (p.Gln1756Profs*74) in the BRCA1 gene, detected in 18.4% (7/38). Interestingly, in four individuals (3.3%) somatic p.Cys61Gly substitution, well-known Polish founder mutation, was detected. To confirm the presence of somatic p.Cys61Gly variant, DNA from FFPE tissues was extracted in duplicates and mutational analysis was performed using PCR followed by HRM in selected samples (#171 and #175). Mutation was detected in both samples; however, in sample #171 p.Cys61Gly variant was identified only in one tumor section, while the second was negative. All pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations reported in the current study are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1. Germline and somatic pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations identified in ctDNA from 121 patients with ovarian cancer.

| Gene | Mutation in corresponding ctDNA | Predicted effect | Type | Case no | FIGO stage | Origin | RS number | Classification A | % reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | c.181T>G | p.Cys61Gly | M | #71 | IIIC | Somatic | rs28897672 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 7 |

| #115 | IIIC | Germline | 51 | ||||||

| c.1793T>A | p.Leu598Ter | N | #85 | IA | Germline | rs80357118 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 51 | |

| c.3296delC | p.Pro1099Leufs*10 | FS | #397 | IIIC | Germline | rs80357815 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 38 | |

| c.3700_3704del | p.Val1234Glnfs*8 | FS | #22 | IIIB | Germline | rs80357609 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 54 | |

| #38 | IIIC | 50 | |||||||

| #66 | IIIC | 70 | |||||||

| c.3756_3759del | p.Ser1253Argfs*10 | FS | #100 | IIIC | Somatic | rs80357868 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 17 | |

| c.5177_5180del | p.Arg1726Lysfs*3 | FS | #162 | IIIC | Germline | rs80357975 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 60 | |

| c.5266dupC | p.Gln1756Profs*74 | FS | #50 | IIIC | Germline | rs397507247 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 43 | |

| #108 | NR | 69 | |||||||

| #314 | IIIC | 49 | |||||||

| #323 | IIIC | 44 | |||||||

| #368 | IV | 46 | |||||||

| #374 | IIIC | 52 | |||||||

| #378 | IIIB | 52 | |||||||

| c.4357+2T>G | r.[=,4186_4357del] p.Arg1377Tyrfs*2 | S | #95 | IIIC | Germline | rs80358152 | Pathogenic [NS] | 49 | |

| c.4484+1G>A | r.[=,4358_4484del] p.Glu1462Ter | S | #395 | IIIC | Germline | rs80358063 | Pathogenic [NS] | 49 | |

| BRCA2 | c.2806_2809del | p.Ala938Profs*21 | FS | #164 | IIIC | Germline | rs80359351 | Pathogenic [NR] | 50 |

| c.5042_5043del | p.Val1681Glufs*7 | FS | #178 | IIIC | Germline | rs80359478 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 49 | |

| c.9097delA | p.Thr3033Leufs*29 | FS | #168 | IIIC | Somatic | rs762120301 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 16.5 | |

| c.9976A>T | p.Lys3326Ter | N | #398 | IV | Germline | rs11571833 | ? B [class 2] | 44 | |

| #411 | IIIC | 48 | |||||||

| BRCA1 (2 variants) | c.[594-2A>C; 641A>G] | r.[=,594_670del] p.Gly183_Lys223del | S | #78 | NR | Germline | rs80358033rs55680408 | Low riskvariant [NS] | 5252 |

| c.3756_3759del | p.Ser1253Argfs*10 | FS | #169 | IIIC | Somatic | rs80357868 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 10 | |

| c.4484+1G>A | r.[=,4358_4484del]p.Glu1462Ter | S | rs80358063 | Pathogenic [NS] | 12 | ||||

| c.1693G>T | p.Glu565Ter | N | #170 | IIIC | Somatic | rs886039963 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 14 | |

| c.3756_3759del | p.Ser1253Argfs*10 | FS | rs80357868 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 20 | ||||

| c.181T>G | p.Cys61Gly | M | #171 | IIIC | Somatic | rs28897672 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 10 | |

| c.3756_3759del | p.Ser1253Argfs*10 | FS | rs80357868 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 10 | ||||

| BRCA1 (3 variants) | c.181T>G | p.Cys61Gly | M | #175 | IIIC | Somatic | rs28897672 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 7 |

| c.3756_3759del | p.Ser1253Argfs*10 | FS | rs80357868 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 4 | ||||

| c.4484+1G>A | r.[=,4358_4484del] p.Glu1462Ter | S | rs80358063 | Pathogenic [NS] | 5 | ||||

| BRCA1 & BRCA2 (2 variants) | c.181T>G | p.Cys61Gly | M | #8 | IV | Somatic | rs28897672 | Pathogenic [class 5] | 21 |

| c.3974_3975insTGCT | p.Thr1325Serfs*4 | FS | Germline | - | Absent C [NR] | 47 | |||

| c.4357+2T>G | r.[=,4186_4357del] p.Arg1377Tyrfs*2 | S | #92 | IIIC | Germline | rs80358152 | Pathogenic [NS] | 48 | |

| c.9976A>T | p.Lys3326Ter | N | Germline | rs11571833 | ? B [class 2] | 50 |

A Variants’ classification reported in the publicly available databases, including the BIC database, BRCA Share™ database, ClinVar and/or the HGMD; variants’ classification reported in the BRCA Exchange database curated by the ENIGMA consortium was presented in square brackets; B this variant should be re-classified in the publicly available databases from prior benign/little clinical significance to likely pathogenic based on the recent findings [18]; C reported as novel pathogenic variant in 1/144 female patient with hereditary breast cancer, but no co-segregation study provided [30]; however, this variant fulfilled the followings ACMG recommendations [29]: PVS1, PM2, PM4, PP3 and PP4, thus it can be clearly classified as pathogenic. FS: frameshift; N: nonsense; M: missense; S: splice; NR: not reported; NS: presence of the variant in the database, but its clinical significance has not yet been specified.

Figure 1. The spectrum of pathogenic germline and somatic mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes detected in 121 ctDNA samples from ovarian cancer patients.

Each number in the circle corresponds with the total number of samples with specific alteration. The germline or somatic origin of mutation is depicted with the red and green color code, respectively. The figure was prepared using the ProteinPaint application [31].

All detected BRCA1/2 variants have been previously reported as pathogenic in the publicly available disease databases (BIC database, BRCA Share™ database, BRCA Exchange database, ClinVar and/or the Human Genome Mutation Database, last accessed May 2017), except one BRCA2 variant (c.9976A>T; Lys3326Ter) that was initially submitted as benign with little clinical significance. However, in line with the recent findings [18], this alteration should be re-classified from the prior benign to likely pathogenic interpretation.

DISCUSSION

To assess the usefulness of ctDNA in screening for BRCA1/2 mutations, we performed next-generation sequencing in a group of 121 unselected patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer. The overall frequency of germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations found in the plasma from ovarian cancer patients was 19% and 6.6%, respectively that is consistent with the previous studies [2–7, 19, 20]. As expected, all germline BRCA1/2 mutations, identified previously in constitutional DNA [9], were detected in circulating DNA, thereby showing 100% specificity and sensitivity of the ctDNA analysis for germline mutations. A slightly higher prevalence of germline alterations (19% vs. 13-15%) was observed in the studied cohort compared to worldwide estimates; however, that is still comparable with our recent reports [9–10]. Indeed, the population's ethnic background with a specific founder mutation and/or the application of various molecular approach with the distinct detection rates might explain these differences in frequency. As for somatic variants, 13 known pathogenic mutations were identified in the additional ~7% of patients that is higher than in our previous report (4.1%) [10]. This difference in frequency of somatic mutations among individuals with the same ethnic background might be explained by intratumoral heterogeneity. In contrast to FFPE sample, which represents only a subpopulation of the whole tumor, analysis of ctDNA provides a comprehensive view of tumor, including all subclones in the primary tumor as well as in distant metastases. That was demonstrated in this study by identifying more than one somatic pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants in four ctDNA samples (Table 1). The presence of intratumoral heterogeneity was also observed while confirming the p.Cys61Gly somatic variant in DNA extracted from two different sections of #171 tumor tissue; the mutation was detected only in one section. Therefore, we strongly believe that ctDNA can give new insights into pathogenesis of ovarian cancer and response of the patients to PARP1 inhibitors.

Among the positive BRCA1/2 variants, c.5266dupC (p.Gln1756Profs*74) and c.181T>G (p.Cys61Gly), both located in the BRCA1 gene, were the most common mutations detected in 18.4% and 13.2% of the studied group, respectively (Figure 1). Both alterations are well-known founder mutations in the Polish population [20, 21]. Interestingly, in the current cohort the c.181T>G was predominantly reported as somatic mutation (Table 1). To date, somatic p.Cys61Gly mutation was detected only in one patient [4]. Presence of germline and somatic variants at the same region may suggest the existence of potential mutational hotspot location. Laitman et al. (2013) reported that the BRCA1 c.68_69delAG (p.Glu23Valfs), one of the most common founder mutations among Ashkenazi women, is not only limited to this population; this alteration arises independently more than once in non-Jewish cohorts, at least in Malaysia and the UK populations [22]. These results support the mutational hotspot theory and may explain the existence of alike variants, both germline and somatic origin.

In addition, we identified the presence of two germline BRCA1 variants c.594-2A>C and c.641A>G (p.Asp214Gly), located in cis position, in a single patient (#78). For a long time, it has been suggested that splice variant c.594-2A>C should be considered as a high-risk pathogenic mutation, because it causes exon 10 skipping. Recently, de la Hoya et al. (2016) demonstrated that BRCA1 c.[594-2A>C;641A>G] is predicted to be a low-risk pathogenic alteration [23].

Despite the promising potential of ctDNA analysis for mutation screening of cancer-related genes, this approach has several limitations. The major drawback of this procedure is the high degree of ctDNA fragmentation and its low concentration in the circulation. A total amount of ctDNA can greatly vary from 0.01% to even 90% depending on the histological type and cancer clinical stage [24]. Although it has been widely accepted that serum contains higher concentrations of ctDNA (at least 2-4 times) than plasma, plasma is the preferably material source, especially in the field of oncology [25]. This increase in serum is likely due to the contamination with constitutional DNA from blood cells during the clotting process. Another technical aspect, the optimal handling protocols, is necessary to avoid hemolysis that might result in high rate of the false negative results. The use of dedicated cell-free DNA blood collection tubes, the proper transport and storage conditions and the optimal time between blood collection and plasma separation will unequivocally minimalize the risk of hemolysis [26, 27]. In addition, the knowledge about the origin and biological mechanisms of ctDNA release is limited. For instance, it is still unclear why the size of plasma DNA samples differs between the several cancer types. Generally, ctDNA is highly fragmented with a median size of 170 bp, but larger fragments (~332 bp and/or ~498 bp) can also be observed in a subset of cancer patients [27, 28]. Taken together, these technical aspects critical for ctDNA analysis, related mostly to pre-analytical procedures, should be validated before its implementation in routine practice.

In this study, we demonstrated that detection of both germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in circulating DNA is feasible and might be helpful as a complementary tool for identification of somatic alterations when the standard diagnostic procedures with using FFPE samples are insufficient. Most tumors are characterized by genomic heterogeneity and due to its clonal evolution, they prone to acquire resistance regardless of the type of therapy. In this context, ctDNA analysis might be used to repeatedly monitor tumor's genomic profile, providing an early warning of its recurrence long before it will be clinically noted. Taken together, ctDNA analysis might be a powerful opportunity for the diagnosis, prognosis and management of cancer patients; however, several pivotal pre-analytical and analytical aspects need to be standardized before its clinical implementation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and sample collection

Among the previously studied group of consecutive 134 patients with ovarian cancer referred for BRCA1/2 genetic testing [9], ctDNA was extracted successfully from the plasma of 131 individuals. All samples for molecular testing were collected prior to therapy. The histological diagnosis of ovarian cancer was evaluated by pathologists, including 72% of individuals with stage III or IV serous ovarian cancer (Table 1). The average patient age at diagnosis was 59 years (range: 27-87). Blood samples that were collected in Cell-Free DNA BCT ® tubes (Streck) were processed within 24 hours after collection and were centrifuged to separate the plasma from the peripheral blood cells. Due to the high risk of contamination with germline material, samples with hemolysis (n=10) were excluded from further analysis. In total, 121 ctDNA samples with an average ctDNA input of 5.5 ng (range: 0.5-39.2 ng) were sequenced.

The research was approved by the local ethics committee at the Medical University of Gdansk. All patients provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

DNA extraction

Circulating tumor DNA was extracted from the separated plasma using cobas cfDNA Sample Preparation Kit (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA from FFPE tumor tissues with cellularity more than 70% was isolated with cobas DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Roche Molecular Diagnostics). Quantity and quality of isolated ctDNA was determined with Qubit Fluoremeter (ThermoFisher Scientific) and 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), respectively.

Mutational analysis

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation screening in ctDNA samples was performed using the BRCA Tumor MASTR Plus assay (Multiplicom) according to the manufacturer's protocol. MiSeq targeted resequencing ~1000 to 2000x (Illumina) was performed and 4% cut-off for the Variant Allele Frequency was applied. The analysis was performed with Sophia DDM (Sophia Genetics), Geneious (Biomatters Ltd.) and Alamut (Interactive Biosoftware) softwares.

The presence of pathogenic somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in ctDNA was confirmed by the independent NGS analysis of second samples. All patients had done the comprehensive analysis of the BRCA1/2 gene testing in the peripheral blood samples as part of our previous study [9], thereby the additional confirmation of germline variants detected in ctDNA was not necessary. The status of somatic variants in FFPE tissue samples was ascertained by high resolution melting (HRM) analysis (Idaho Technology Inc.).

The nomenclature of the alterations was based on BRCA1 mRNA sequence NM_007294.3 and BRCA2 mRNA sequence NM_000059.3 according to the recommendations of the Human Genome Variety Society (http://varnomen.hgvs.org/). Variants’ interpretation pathogenicity was performed in line with the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) recommendations [29].

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who agreed to participate in the current study. We thank the Sophia Genetics team, especially Christian Pozzorini who performed bioinformatics analysis.

Dr Koczkowska is also affiliated with the Department of Genetics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA.

Abbreviations

- ctDNA

circulating tumor DNA

- FFPE

formalin fixed paraffin embedded

- NGS

next generation sequencing

- PARP1

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

Author contributions

M.R. - sample selection, mutational analysis, data interpretation and manuscript preparation; M.K. - sample selection, mutational analysis, data interpretation and manuscript preparation; M.Ż. - mutational analysis, data interpretation; A.K. - performed ctDNA extraction; W.B. - samples selection; J.L. - participated in conceiving the study; M.S. - participated in clinical samples characterization and selection; B.W. - supervised NGS analysis, participated in data interpretation, conceiving the study and manuscript preparation, coordinated the study. All authors read and approved the final draft.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Science Centre grant: 2011/02/A/NZ2/00017.

Online databases

BIC Database: https://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/

BRCA Share™ Database: http://www.umd.be/BRCA1/

BRCA Exchange Database: http://brcaexchange.org/

ClinVar Database: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/

Human Genome Mutation Database: http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php

Cosmic Database: http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, Krischer JP, Fiorica J, Arango H, LaPolla J, Hoffman M, Martino MA, Wakeley K, Wilbanks G, Nicosia S, Cantor A, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005;104:2807–2816. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, Rosen B, Bradley L, Fan I, Tang J, Li S, Zhang S, Shaw PA, Narod SA. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1694–1706. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merajver SD, Pham TM, Caduff RF, Chen M, Poy EL, Cooney KA, Weber BL, Collins FS, Johnston C, Frank TS. Somatic mutations in the BRCA1 gene in sporadic ovarian tumours. Nat Genet. 1995;9:439–443. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster KA, Harrington P, Kerr J, Russell P, DiCioccio RA, Scott IV, Jacobs I, Chenevix-Trench G, Ponder BA, Gayther SA. Somatic and germline mutations of the BRCA2 gene in sporadic ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3622–3625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berchuck A, Heron KA, Carney ME, Lancaster JM, Fraser EG, Vinson VL, Deffenbaugh AM, Miron A, Marks JR, Futreal PA, Frank TS. Frequency of germline and somatic BRCA1 mutations in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2433–2437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennessy BT, Timms KM, Carey MS, Gutin A, Meyer LA, Flake DD, 2nd, Abkevich V, Potter J, Pruss D, Glenn P, Li Y, Li J, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 could expand the number of patients that benefit from poly (ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3570–3576. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougherty BA, Lai Z, Hodgson DR, Orr MCM, Hawryluk M, Sun J, Yelensky R, Spencer SK, Roberston JD, Ho TW, Fielding A, Ledermann JA, Barrett JC. Biological and clinical evidence for somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 as predictive markers for olaparib response in high-grade serous ovarian cancers in the maintenance setting. Oncotarget. 2017;8:43653–43661. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratajska M, Krygier M, Stukan M, Kuźniacka A, Koczkowska M, Dudziak M, Śniadecki M, Dębniak J, Wydra D, Brozek I, Biernat W, Borg A, Limon J, et al. Mutational analysis of BRCA1/2 in a group of 134 consecutive ovarian cancer patients. Novel and recurrent BRCA1/2 alterations detected by next generation sequencing. J Appl Genet. 2015;56:193–198. doi: 10.1007/s13353-014-0254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koczkowska M, Zuk M, Gorczynski A, Ratajska M, Lewandowska M, Biernat W, Limon J, Wasag B. Detection of somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in ovarian cancer - next-generation sequencing analysis of 100 cases. Cancer Med. 2016;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.1002/cam4.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, Friedlander M, Powell B, Bell-McGuinn KM, Scott C, Weitzel JN, Oaknin A, Loman N, Lu K, Schmutzler RK, Matulonis U, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong PC, Yap TA, Boss DS, Carden CP, Mergui-Roelvink M, Gourley C, De Greve J, Lubinski J, Shanley S, Messiou C, A’Hern R, Tutt A, Ashworth A, et al. Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase inhibition: frequent durable responses in BRCA carrier ovarian cancer correlating with platinum-free interval. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2512–2519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ledermann JA, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Fielding A, Spencer S, et al. Overall survival in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent serous ovarian cancer receiving olaparib maintenance monotherapy: an updated analysis from a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30376-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandel P, Metais P. Les acides nucléiques du plasma sanguin chez l’homme. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1948;142:241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christie EL, Fereday S, Doig K, Pattnaik S, Dawson SJ, Bowtell DDL. Reversion of BRCA1/2 germline mutations detected in circulating tumor DNA from patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1274–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson ER, Gorringe KL, Rowley SM, Li N, McInerny S, Wong-Brown MW, Devereux L, Li J, Hopper J, et al. Lifepool Investigators Reevaluation of the BRCA2 truncating allele c.9976A>T (p.Lys3326Ter) in a familial breast cancer context. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14800. doi: 10.1038/srep14800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilton JL, Geisler JP, Rathe JA, Hattermann-Zogg MA, DeYoung B, Buller JE. Inactivation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Ins. 2002;94:1396–1406. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.18.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brozek I, Ochman K, Debniak J, Morzuch L, Ratajska M, Stepnowska M, Stukan M, Emerich J, Limon J. High frequency of BRCA1/2 germline mutations in consecutive ovarian cancer patients in Poland. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno/2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratajska M, Brozek I, Senkus-Konefka E, Jassem J, Stepnowska M, Palomba G, Pisano M, Casula M, Palmieri G, Borg A, Limon J. BRCA1 and BRCA2 point mutations and large rearrangements in breast and ovarian cancer families in Northern Poland. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laitman Y, Feng BJ, Zamir IM, Weitzel JN, Duncan P, Port D, Thirthagiri E, Teo SH, Evans G, Latif A, Newman WG, Gershoni-Baruch R, Zidan J, et al. Haplotype analysis of the 185delAG BRCA1 mutation in ethnically diverse populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:212–216. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Hoya M, Soukarieh O, López-Perolio I, Vega A, Walker LC, van Ierland Y, Baralle D, Santamariña M, Lattimore V, Wijnen J, Whiley P, Blanco A, Raponi M, et al. Combined genetic and splicing analysis of BRCA1 c.[594-2A>C; 614A>G] highlights the relevance of naturally occurring in-frame transcripts for developing disease gene variant classification algorithms. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2256–2268. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, Bertlett BR, Wang H, Luber B, Alani MR, Antonarakis ES, Azad NS, Bardelli A, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung M, Klotzek S, Lewandowski M, Fleischhacker M, Jung K. Changes in concentration of DNA in serum and plasma during storage of blood samples. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1028–1029. doi: 10.1373/49.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Messaoudi S, Rolet F, Mouliere F, Thierry AR. Circulating cell free DNA: Preanalytical considerations. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;424:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heitzer E, Ulz P, Geigl JB. Circulating tumor DNA as a liquid biopsy for cancer. Clin Chem. 2015;61:112–123. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.222679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mouliere F, Rosenfeld N. Circulating tumor-derived DNA is shorter than somatic DNA in plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3178–3179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501321112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hedge M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cybulski C, Lubiński J, Wokołorczyk D, Kuźniak W, Kashyap A, Sopik V, Huzarski T, Gronwald J, Byrski T, Szwiec M, Jakubowska A, Górski B, Dębniak T, et al. Mutations predisposing to breast cancer in 12 candidate genes in breast cancer patients from Poland. Clin Genet. 2015;88:366–370. doi: 10.1111/cge.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou X, Edmonson MN, Wilkinson MR, Patel A, Wu G, Liu Y, Li Y, Zhang Z, Rusch MC, Parker M, Becksfort J, Downing JR, Zhang J. Exploring genomic alteration in pediatric cancer using ProteinPaint. Nat Genet. 2016;48:4–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]