Abstract

To downregulate gene expression in cyanobacteria, we constructed NOT gate genetic circuits using orthogonal promoters and their cognate repressors regulated translationally by synthetic riboswitches. Four NOT gates were tested and characterized in five cyanobacterial strains using fluorescent reporter-gene assays. In comparison to alternative systems used to downregulate gene expression in cyanobacteria, these NOT gates performed well, reducing YFP reporter expression by 4 to 50-fold. We further evaluated these NOT gates by controlling the expression of the ftsZ gene, which encodes a prokaryotic tubulin homolog that is required for cell division and is essential for Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. These NOT gates would facilitate cyanobacterial genetic engineering or the study of essential cellular processes.

Keywords: cyanobacteria, synthetic biology, circuits, genetic engineering, downregulation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

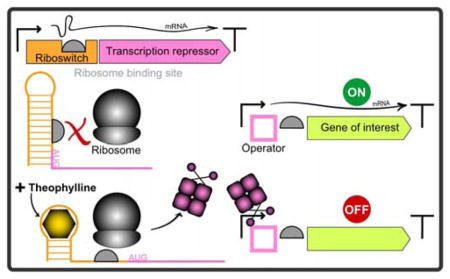

Inducible downregulation of gene expression has many applications, including studying fundamental biological processes or engineering metabolic pathways to make renewable bioproducts. A function that outputs an OFF state when the input is ON is referred to as a NOT gate genetic circuit in the synthetic biology lexicon. Several mechanisms can provide the repressing function of a NOT gate. Most use an inducible input promoter to drive a transcriptional repressor, which binds an operator sequence within a cognate promoter and turns OFF the output. Natural repressors including the cI phage repressor, and the LacI and TetR repressors1–3, have been used for synthetic circuits in Escherichia coli. However, NOT gate circuits have yet to be reported for cyanobacteria. Alternative systems based on CRISPRi have been recently developed for gene repression in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Synechococcus PCC 7002, and S. elongatus PCC 7942.4–6

Several inducible systems have been constructed for conditional gene expression in cyanobacteria. Some systems used native promoters, induced by addition or depletion of metal ions or macronutrients.7 However, orthogonal systems are preferred because they are less likely to exhibit crosstalk or affect normal host functions, but few have been developed for cyanobacteria.8–11 Most are based on LacI-regulated promoters that drive the expression of lacZYA for lactose catabolism in E. coli, and we have used the LacI system in the work presented here. In wild-type (WT) E. coli, LacI primarily binds a lac operator sequence, lacO1, which overlaps the transcription start site (TSS) by 1 base pair.11 The repression exerted by LacI is further enhanced through DNA-looping, which involves lacO2 and lacO3.12 Of the three operators, lacO1 binds LacI with the greatest affinity but a synthetic and perfectly symmetric operator sequence lacOsym binds LacI with an even greater affinity.13 Huang et al.14 characterized two LacI-regulated promoters, Ptrc and Ptrc2O, in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Ptrc contains the Ptrc core promoter including lacO1, and Ptrc2O contains the core and an additional lacOsym operator 89 base pairs upstream of the TSS to enhance LacI repression through DNA-looping. In the absence of LacI, both promoters were shown to be quite strong (> 80 × stronger than PrnpB) in Synechocystis. However, Ptrc was poorly repressed by LacI (25% decrease in expression), whereas Ptrc2O was efficiently repressed (95% decrease in expression) but was poorly induced (induction of only 10%) by isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

We chose to determine the utility in cyanobacteria of another orthogonal inducible promoter. Vanillate-inducible gene expression systems have been shown to be tightly controllable in Caulobacter crescentus and Sphingomonas melonis.15–16 The regulation of vanillate catabolism has been well studied in Corynebacterium glutamicum. VanR represses the expression of the vanABK operon by binding to a short sequence with dyad symmetry downstream of the promoter. Expression of the vanABK operon is induced with vanillate or ferrulate.17

To control protein expression of transcriptional repressors, we used theophylline-responsive riboswitches.18 A riboswitch is an mRNA element composed of an aptamer sequence that binds a cognate effector molecule or ligand, and flanking sequences that adopt an alternative secondary conformation to modulate gene expression after binding of the effector molecule. In prokaryotes, riboswitches are often located in 5′-untranslated regions of mRNA transcripts where they allow or prevent access to the ribosome-binding site, form or disrupt a transcriptional terminator, or undergo self-cleavage after binding of a ligand.19 A set of synthetic theophylline-responsive riboswitches that control translation, originally developed and evaluated in eight different bacterial species by Topp et al.,18 have since been shown to provide robust control of gene expression in several phylogenetically diverse cyanobacteria.20–21

In this report, we sought to rationally design, construct, and characterize NOT gate genetic circuits using transcriptional repressors controlled by riboswitches to downregulate gene expression in five diverse strains of cyanobacteria, including three model organisms, Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, and Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, as well as two recent isolates, Leptolyngbya sp. BL0902, and Synechocystis sp. WHSyn.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Because the trc2O promoter has high activity levels in the absence of LacIq and is strongly repressed in the presence of LacIq,14 we initially designed NOT gates in which LacIq expression was controlled by theophylline-responsive riboswitches, and the Ptrc2O promoter controlled the target gene(s). In addition, we determined that C. glutamicum’s Pvan promoter and its cognate repressor VanR could be used to produce a NOT gate with a relatively low transcription strength, a characteristic necessary for some genetic engineering goals. In comparison to Ptrc2O, the Pvan promoter, in the absence of VanR, exhibited low levels of activity in cyanobacteria. Fluorescence levels of a YFP reporter driven by Pvan were 3 to 8 percent of the expression from Ptrc2O, depending on the cyanobacterial strain (Figure S1 and S2). The Pvan promoter was fully repressed by VanR driven by the synthetic consensus PconII promoter in 4 different strains of cyanobacteria (data not shown). Therefore, we also designed theophylline-controlled NOT gates using vanR and Pvan to achieve lower ON-state transcription activity. The six riboswitches characterized by Ma et al.21 displayed a range of induction ratios, with different basal (uninduced) and maximal (induced by theophylline) levels of expression in different strains. Riboswitch F has high induction ratios, but in preliminary experiments (data not shown), its uninduced basal expression of repressors was too high and caused repression of the NOT gates even in the ON state. Therefore, we used riboswitches B and C, which have high induction ratios but very low levels of basal expression in the absence of theophylline.21

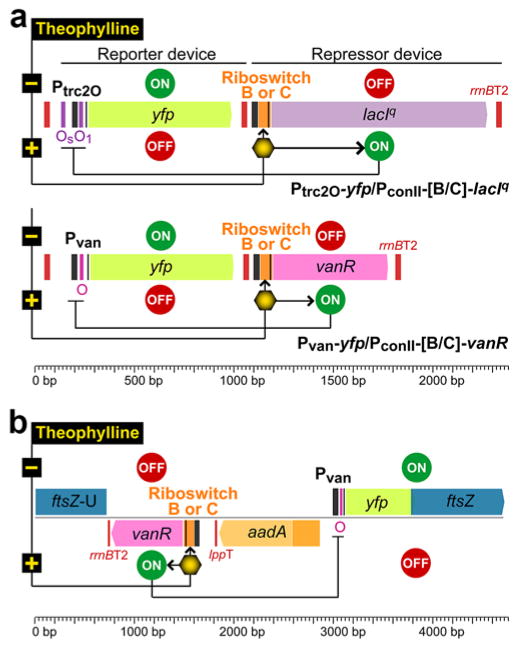

We constructed four NOT gates (Figure 1, Table S1). The repressor devices are composed of PconII driving the expression of lacIq or vanR, with translation controlled by riboswitch B or C. The reporter devices are composed of the cognate repressible promoters Ptrc2O or Pvan driving the expression of YFP. The default ON-state in the absence of inducer allows expression of YFP because the transcriptional repressor is not expressed. For the OFF-state, the addition of theophylline induces translation of the transcriptional repressor, which then inhibits transcription of the yfp gene. For S. elongatus, the repressor and reporter devices were constructed on suicide plasmids and inserted at 2 separate neutral sites, NS1 and NS322–23, respectively, in the chromosome, whereas both devices were cloned together in a self-replicating broad host range plasmid based on RSF1010 for the other four cyanobacterial strains (Table S1). S. elongatus control strains carrying the repressor or the reporter device alone also carried a spectinomycin/streptomycin- or gentamycin-resistance marker in the other neutral site to allow growth in the same medium as the experimental strains. Experimental and control strains of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Leptolyngbya sp. BL0902, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, and Synechocystis sp. WHSyn all carried a kanamycin/neomycin-resistance marker on a shuttle plasmid. The strains that were constructed and characterized in this study are listed in Table S2. For each strain, 3 independent clones were used as biological replicates.

Figure 1.

NOT gate genetic circuits based on the Ptrc2O/lacIq and the Pvan/vanR promoter/repressor systems controlled with theophylline-responsive riboswitches B or C. (a) Circuits constructed in RSF1010Y25F shuttle vector to control YFP expression levels; (b) Pvan/vanR NOT gates assembled with an antibiotic resistance marker and a yfp-ftsZ translational fusion to replace the ftsZ native locus in S. elongatus by double-crossover recombination. Os and O1 are operator sequences for LacIq; O is the operator sequence for VanR; rrnBT2 and lppT are terminator sequences. The transcription of lacIq and vanR is driven by PconII (black bar).

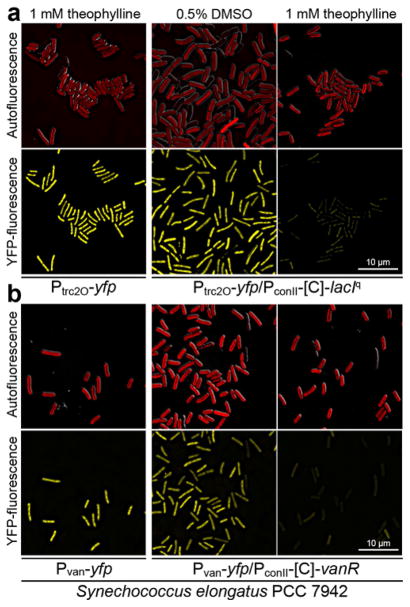

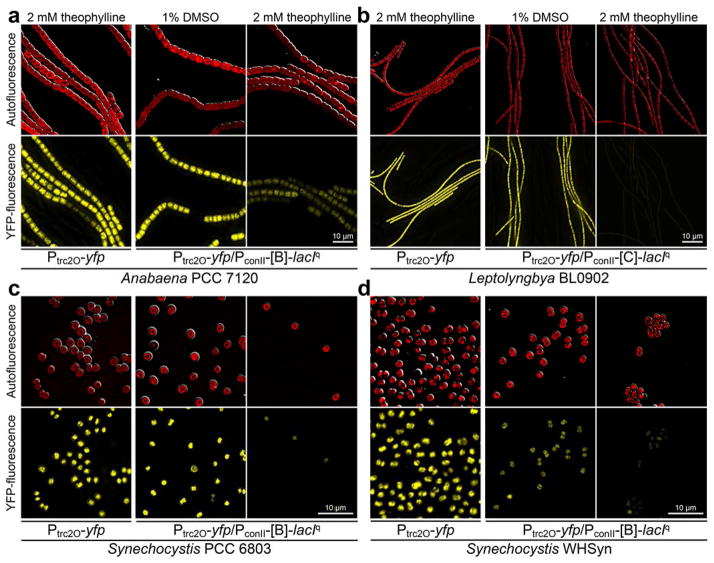

To characterize our set of NOT gates in the 5 cyanobacteria, we measured reporter fluorescence after induction with theophylline over a period of 5 days. In addition to strains carrying both the repressor device and the cognate reporter device, we included strains carrying the repressor devices alone to measure background fluorescence, and strains carrying the reporter devices alone to measure maximal constitutive expression levels without repression. Fluorescence microscopy carried out 3 days after induction with theophylline showed that both the Ptrc2O/LacIq and the Pvan/VanR NOT gates effectively repressed the expression of YFP in S. elongatus (Figures 2, S3, and S4). In the four other species, the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates functioned well and repressed the expression of YFP (Figure 3 and S5 to S8). However, for these strains, the Pvan/VanR NOT gates failed to express the YFP reporter even in the ON-state (data not shown), presumably because the basal level of VanR expression was sufficient to repress the Pvan promoter, and therefore these strains could not be characterized further.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of S. elongatus harboring the YFP reporter devices alone in inducing conditions with theophylline, or the NOT gates driving YFP, in which (a) LacIq and (b) VanR are controlled by riboswitch C in both uninduced (ON state) and induced (OFF state) conditions. Top panels show autofluorescence of photosynthetic pigments merged with differential interference contrast (DIC); Bottom panels show YFP fluorescence. Exposure time, brightness, and contrast were kept constant for the YFP images that use the same reporter device, but were different for the strains carrying Ptrc2O and Pvan reporter devices. The photomicrographs were taken on the third day after addition of theophylline or DMSO vehicle control.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of (a) Anabaena PCC 7120, (b) Leptolyngbya BL0902, (c) Synechocystis PCC 6803, and (d) Synechocystis WHSyn harboring the reporter device alone in inducing conditions, or a Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gate controlled by riboswitch B (or C for Leptolyngbya) in both uninduced and induced conditions. The photomicrographs were taken on the third day after addition of theophylline or DMSO vehicle control.

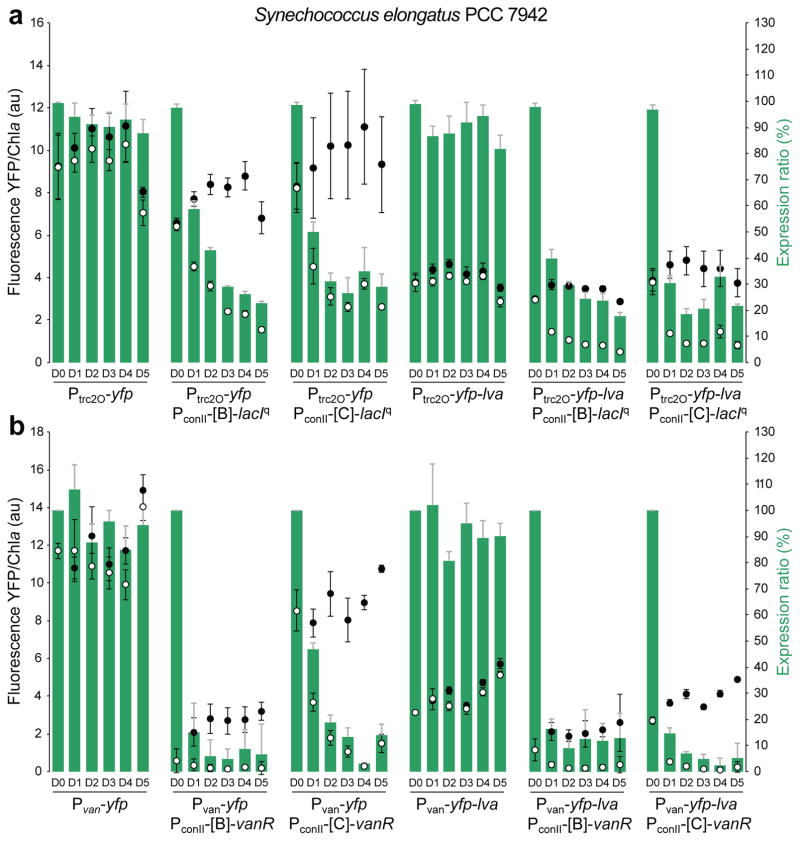

A fluorescence plate reader was used to obtain quantitative YFP reporter data for 5 days after induction of repressor expression with theophylline (Figures 4 and 5). In general, levels of YFP fluorescence for S. elongatus strains carrying either Ptrc2O/LacIq or Pvan/VanR NOT gates showed a large decrease in the expression ratio (Figure 4, bars, shown as percent OFF state/ON state) after 1 day, which continued to decrease over the next few days. Lower expression ratios represent a lower relative OFF state and better NOT gate function. As reported above, Ptrc2O had a stronger level of expression than Pvan in all strains, and the maximal YFP fluorescence level of S. elongatus carrying Ptrc2O-yfp was 17-fold higher than for those carrying Pvan-yfp (Figure S2).

Figure 4.

Characterization of the NOT gates in S. elongatus over a time course of 5 days post-induction. (a) Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates; (b) Pvan/VanR NOT gates. Fluorescence intensities, normalized to chlorophyll a (Chla), of the ON (closed circles, with 0.5% DMSO vehicle control) and OFF (open circles, with 1 mM theophylline) states are shown on the left axes. Expression ratios (green bars) shown on the right axes were determined by dividing fluorescence levels in the ON state over the OFF state. The horizontal axes show data for pre-induction (D0) and days post-induction (D1–D5) for strains containing the indicated reporter device alone or the NOT gates. Different optimal settings (gain adjustments) were used to measure fluorescence intensities for the Ptrc2O/LacIq and Pvan/VanR NOT gates; therefore, intensities between the two NOT gates cannot be directly compared. Error bars indicate standard deviation of 3 biological replicates.

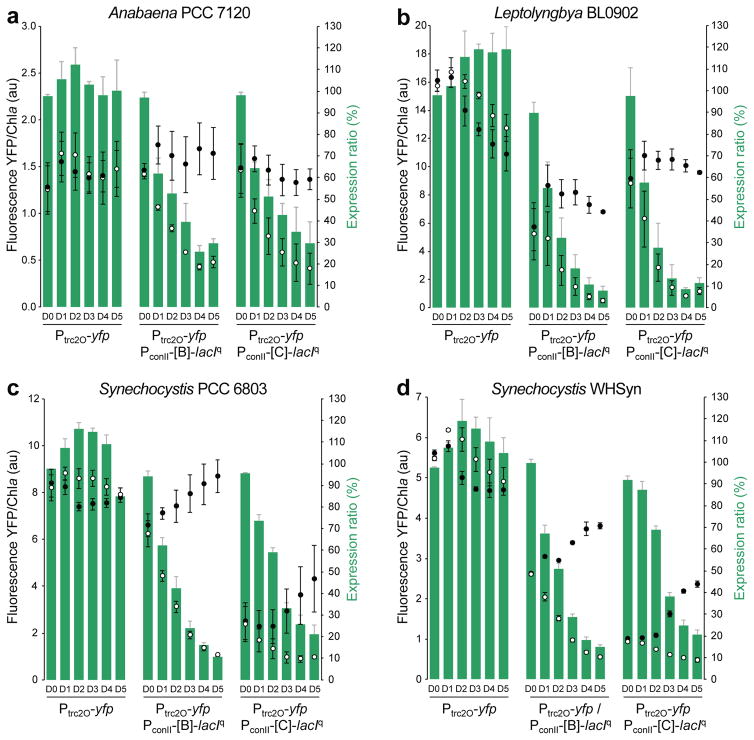

Figure 5.

Characterization of the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates in (a) Anabaena PCC 7120, (b) Leptolyngbya BL0902, (c) Synechocystis PCC 6803, and (d) Synechocystis WHSyn over a time course of 5 days post-induction. Fluorescence intensities of the ON (closed circles, with 1% DMSO vehicle control) and OFF (open circles, with 2 mM theophylline) states are shown on the left axes. Expression ratios (green bars) are shown on the right axes. Error bars indicate standard deviation of 3 biological replicates.

For the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gate (Figure 4a), riboswitch B allowed a low basal level of LacIq expression in the absence of theophylline (ON state). This was seen as a 20% decrease from the maximal YFP fluorescence produced by the Ptrc2O-yfp reporter alone (Figure 4a, closed circles). The LacIq NOT gate with riboswitch C had a lower level of uninduced repressor expression and showed maximal fluorescence levels without theophylline. After induction of LacIq with theophylline (Figure 4a, open circles), expression ratios decreased for both riboswitches B and C to about 20–30% by day 5, with the lowest expression produced by riboswitch B.

Strains carrying NOT gates with VanR controlled by either riboswitch B or C had significantly lower fluorescence in the uninduced ON-state than those carrying Pvan-yfp reporter alone, about 81% reduced with riboswitch B and 26% reduced with riboswitch C (Figure 4b). These results indicate significant basal expression of VanR, but a lower basal expression with riboswitch C. After induction of VanR with theophylline, Pvan/VanR NOT gates controlled by either riboswitch B or C had very low levels of fluorescence and low expression ratios. For VanR controlled by riboswitch B, OFF-state YFP fluorescence was very low by day 2 following induction with expression ratios of only about 6%. Riboswitch C produced the lowest expression ratio of only about 3% on day 4 (Figure 4b).

In a study of the circadian clock in S. elongatus, the half-life of YFP was estimated to be 12.8 hours, and this was reduced to 5.6 hours by adding an LVA degradation tag24. To obtain a more accurate measure of the repression kinetics, an LVA degradation tag was added to the C-terminal end of YFP to reduce its half-life. Overall, fluorescence levels were considerably lower in the strains carrying yfp-lva (Figure 4). For the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates, fluorescence levels for YFP-LVA were typically 55 to 65% lower than for untagged YFP. For the Pvan/VanR NOT gates, maximal levels of fluorescence from the promoter alone were 66% lower for the destabilized YFP-LVA. The Pvan/VanR NOT gate in which VanR was controlled by riboswitch C showed lower fluorescence for YFP-LVA compared with untagged YFP in both the ON and OFF states. However, the Pvan/VanR NOT gate controlled by riboswitch B showed little difference in fluorescence between YFP and destabilized YFP-LVA, presumably because of its relatively low basal promoter activity in the ON state. The destabilized YFP-LVA showed faster decreases in expression ratios and very low OFF-state reporter fluorescence for Pvan/VanR NOT gates controlled by riboswitch B or C. The lowest expression ratio was as low as 2% on day 4 (50-fold repression) for the strain carrying destabilized YFP-LVA and the Pvan/VanR NOT gate controlled by riboswitch C. In general, riboswitch C had a higher dynamic range with higher ON-state fluorescence compared to riboswitch B, and riboswitch B generally showed the lowest OFF-state fluorescence.

The Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates were further characterized in 4 diverse cyanobacterial strains: Anabaena PCC 7120, Leptolyngbya BL0902, Synechocystis PCC 6803, and Synechocystis WHSyn (Figure 5). The Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates controlled by either riboswitch B or C functioned relatively well in all 4 strains, but with different quantitative characteristics. The lowest expression ratios, usually reached by day 4 or 5 after induction, were 26% in Anabaena, 8% in Leptolyngbya, 13% in Synechocystis PCC 6803 and 15% in Synechocystis WHSyn, compared with 23% in S. elongatus. In Anabaena (Figure 5a), the ON-state levels of YFP-reporter fluorescence for both riboswitch B and C were comparable with fluorescence levels of the reporter alone, indicating minimal basal activity of LacIq in the absence of theophylline. After induction, Anabaena showed expression ratios that were similar to those for S. elongatus with the same NOT gate and reporter constructs. In Leptolyngbya (Figure 5b), expression ratios were lower for both B and C riboswitches compared to other strains, indicating that expression and/or activity of the LacIq repressor was higher in Leptolyngbya. In the 2 strains of Synechocystis (Figures 5c and 5d), the ON-state levels of fluorescence for the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates controlled by both riboswitches were lower than for the reporter alone. After induction of the OFF-state with theophylline, both Synechocystis strains showed a gradual decrease in YFP fluorescence similar to the other cyanobacterial strains.

Riboswitches B and C both functioned well for the VanR-based NOT gates in S. elongatus and for the LacIq-based NOT gates in all 5 cyanobacterial strains but showed quantitative differences. For example, differences were observed between the two riboswitches for the Pvan/VanR NOT gate in S. elongatus (Figure 4b), with higher YFP ON- and OFF-state expression for riboswitch C, which indicates lower expression of the VanR repressor for both uninduced and induced states. In Anabaena and Leptolyngbya (Figure 5a and 5b), the two riboswitches showed similar expression ratios for Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates, but there were notable differences for the Synechocystis strains PCC 6803 and WHSyn (Figure 5c and 5d), in which riboswitch B showed higher ON-state YFP fluorescence compared to riboswitch C.

To evaluate our NOT gate circuits for the control of an essential gene in S. elongatus, we used them to express FtsZ for which changes in expression would result in strong cellular morphology phenotypes. FtsZ is a prokaryotic tubulin homolog that polymerizes into a ring structure during cell division25 in most bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotic organelles. FtsZ is essential in S. elongatus.26–27 The S. elongatus ftsZ gene is present at a single locus and its overexpression results in altered cell morphologies.28 Furthermore, a YFP-FtsZ fusion protein was shown to be functional and allows in vivo localization in S. elongatus.29 Although the expression of yfp-ftsZ from Ptrc in the presence of LacI was shown by immunoblot to be about 55-fold higher than the endogenous ftsZ, S. elongatus cells had normal morphology and FtsZ ring formation at the mid cell.29

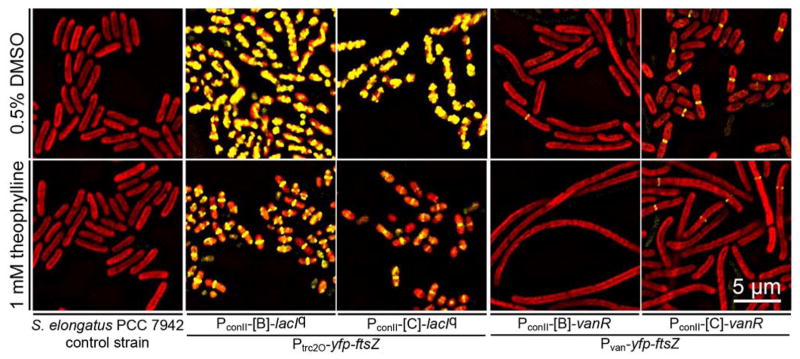

We replaced the native ftsZ locus in S. elongatus with yfp-ftsZ translational fusions controlled by each of the 4 different NOT gates (Figure 1b). Segregation of the yfp-ftsZ fusions occurred normally during strain constructions, and strains harboring the yfp-ftsZ fusions were viable (Figure S9). Control of YFP-FtsZ expression by the Ptrc2O/LacIq and Pvan/VanR NOT gates resulted in predictable phenotypes (Figure 6). For the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gate, yfp-ftsZ was strongly overexpressed in the ON-state (DMSO control), as indicated by the high abundance of YFP-FtsZ. In most cells, there were large amounts of YFP-FtsZ in the cytoplasm, and the cells were usually small and had abnormal shapes. After induction of the OFF state with theophylline, the abundance of YFP-FtsZ decreased and normal ring structures were present at the center of the cells. However, the cells were significantly shorter than normal, suggesting that the amounts of functional FtsZ were higher than WT levels. Mori and Johnson28 showed that the overexpression of WT ftsZ with a trc promoter in S. elongatus halts cell division and results in filamentous cells on solid medium (BG11 with 1.5% agar). Our results showed a different phenotype associated with the overexpression of yfp-ftsZ; however, the cells were grown in different conditions and the levels of functional YFP-FtsZ translational fusion compared to WT FtsZ is unknown. Nevertheless, both studies indicate that overexpression of FtsZ alters normal cell division.

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of S. elongatus in which the native ftsZ locus was replaced by a yfp-ftsZ translational fusion controlled with the 4 NOT gates in the ON (with 0.5% DMSO vehicle control) and OFF (with 1 mM theophylline) states. YFP fluorescence images, showing YFP-tagged FtsZ (shown in yellow), are merged with autofluorescence images (shown in red).

In the Pvan/VanR NOT gate with VanR controlled by riboswitch B, cells in the ON-state produced only rare ring structures and were longer than WT cells (Figure 6). With riboswitch C, FtsZ rings were apparent in many cells and cell morphology was nearly normal. In the OFF-state, after theophylline addition, cells with the NOT gate controlled by riboswitch B were very elongated and YFP-FtsZ ring structures were not visible, indicating very low expression. Riboswitch C produced long cells with a few YFP-FtsZ ring structures, indicating a low but somewhat higher level of expression. These experiments are consistent with the reporter experiments and indicate that the Ptrc2O promoter is quite strong and can produce overexpression phenotypes, and that the weaker Pvan promoter is probably more appropriate for experiments designed to examine the effects of depletion of a normal endogenous protein. Nevertheless, for all strains, the induction of the OFF state resulted in phenotypic changes resulting from a decrease of functional FtsZ levels in the cells. Modifications of the Ptrc2O and Pvan core promoter sequences could be used to fine tune the ON state expression levels for specific experimental applications.

The NOT gate genetic circuits developed in this study embody a new application of synthetic ligand-responsive riboswitches for genetic engineering or the study of essential cellular processes in cyanobacteria. The translational control of the transcriptional repressors LacIq and VanR using riboswitches effectively repressed expression of genes driven by their cognate promoters in diverse cyanobacterial strains. Further modification of these circuits could be achieved by using different promoters and riboswitches to drive expression of the repressors to produce variations in the levels of ON-state and OFF-state expression.

In comparison to alternative systems developed to downregulate gene expression in cyanobacteria, the NOT gates devised in this study performed well. In a study using a tetracycline-regulated promoter to control the E. coli IS10 RNA-OUT sRNA, GFP expression levels were reduced by up to 59% in Synechococcus PCC 7002.30 Regulation based on CRISPRi in which dCas9 and/or the guide RNAs were controlled by a tetracycline-regulated promoter repressed the expression of a fluorescent reporter protein by up to 94% in Synechocystis PCC 68034 and by up to 95% in Synechococcus PCC 7002.5 In comparison, the results presented here show that expression ratios decreased by up to 87% using the Ptrc2O/LacIq NOT gates controlled with riboswitch B in Synechocystis PCC 6803 and decreased by up to 98% using the Pvan/VanR NOT gates in S. elongatus. However, we note that CRISPRi based systems have potential advantages as they can be used to repress multiple genes at once, without the need to engineer multiple individual promoters. Therefore, using theophylline synthetic riboswitches to control the expression of dCas9 may be another useful strategy to create inducible NOT gate circuits.

METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C with LB medium in broth culture or on agar plates, supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Cyanobacterial strains Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Leptolyngbya sp. BL0902, Synechocystis PCC 6803, and Synechocystis WHSyn were grown in BG11 medium31 as liquid cultures at 30 °C with continuous shaking or on agar plates (40 ml, 1.5% agarose) and continuous illumination of 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 was grown in similar conditions but with continuous illumination of 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1. All cultures were grown in air with fluorescent cool white bulbs as the light source. Culture media for recombinant cyanobacterial strains were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics.

Strain construction

Plasmid DNA was introduced into S. elongatus by natural transformation using standard protocols.22 Recombinant DNA carrying NOT GATE genetic circuits and an antibiotic resistance device were integrated into the chromosome at neutral site 1 (NS122) and 3 (NS323), or within the ftsZ native locus by homologous recombination. For the other cyanobacterial strains, recombinant DNA carried on the self-replicating broad host range plasmid shuttle vector RSF1010Y25F32 was introduced into cells through biparental conjugations from E. coli following published protocols.33–34 Plasmids and cyanobacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 and S2, respectively.

Induction assays

Measurements were taken from 3 independent clones for each strain. To obtain reproducible data, all strains were pre-grown for 3 days in liquid culture prior to induction. Cultures were adjusted to an optical density at 750 nm (OD750) of 0.1 before pre-growth, induction, and fluorescence measurements. For induction with theophylline, 2.5 ml cultures were grown in glass tubes (16 × 100 mm) set up on shakers (150 rpm) at 30 °C under continuous illumination of 70 or 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Depending on the assay, cultures were adjusted to 1 or 2 mM theophylline (Sigma-Aldrich) or an equal volume of the DMSO vehicle (final concentration of 0.5 or 1.0%, respectively) as a control. In assays carried out over several days, at the end of the second day post induction (D2), a volume of fresh media with the appropriate inducer or vehicle control was added back to equal the volume removed by sampling. The volume of medium collected over several days and the compensating amount of fresh media added were the same for all strains that were compare with each other as part of the same experiment. Optical densities and emission intensities of fluorescent proteins were measured from 200 μl of culture in 96 well plates with a Tecan Infinite(R) M200 plate reader (TECAN). Black-walled 96 well plates (Greiner) were used to measure fluorescence intensities. The excitation and emission wavelengths were set to EX490/9 and EM535/20 for YFP and EX425/9 and EM680/20 for chlorophyll a (Chla).

Further details on strain growth and genetic selection, plasmid and strain construction, microscopy, and statistical analyses are provided in the associated content. All plasmid maps were deposited in the ACS Synthetic Biology Registry (https://acs-registry.jbei.org/folders/12).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Arushi Atluri, Vivian Pham, Yvonne M. Reyes, and Matthew Paddock for their contributions to the construction and/or the evaluation of several genetic devices, Christian Erikson for useful discussion on statistical analyses, and Susan Cohen for a plasmid harboring a yfp-ftsZ translational fusion for S. elongatus. This work was supported by the Department of Energy [DE-EE0003373] and the California Energy Commission [CILMSF #500-10-039]. A.T.M. was supported by the Life Sciences Research Foundation, sponsored by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AT and JWG designed the study with input from ATM and SSG; AT, ATM, and MO performed the experiments; AT and JWG wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: XXX.

Additional figures (S1–S9), tables (S1–S3), and methods (PDF)

Raw fluorescence intensities (XLSX)

References

- 1.Yokobayashi Y, Weiss R, Arnold FH. Directed evolution of a genetic circuit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16587–16591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252535999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;403:339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elowitz MB, Leibler S. A synthetic oscillatory network of transcriptional regulators. Nature. 2000;403:335–338. doi: 10.1038/35002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao L, Cengic I, Anfelt J, Hudson EP. Multiple gene repression in cyanobacteria using CRISPRi. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5:207–212. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon GC, Korosh TC, Cameron JC, Markley AL, Begemann MB, Pfleger BF. CRISPR interference as a titratable, trans-acting regulatory tool for metabolic engineering in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. Metab Eng. 2016;38:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang CH, Shen CR, Li H, Sung LY, Wu MY, Hu YC. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for gene regulation and succinate production in cyanobacterium S. elongatus PCC 7942. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:196. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0595-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berla BM, Saha R, Immethun CM, Maranas CD, Moon TS, Pakrasi HB. Synthetic biology of cyanobacteria: unique challenges and opportunities. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:246. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhai J. Strong and regulated promoters in the cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geerts D, Bovy A, de Vrieze G, Borrias M, Weisbeek P. Inducible expression of heterologous genes targeted to a chromosomal platform in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Microbiol. 1995;141(Pt 4):831–841. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang HH, Lindblad P. Wide-dynamic-range promoters engineered for cyanobacteria. J Biol Eng. 2013;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camsund D, Heidorn T, Lindblad P. Design and analysis of LacI-repressed promoters and DNA-looping in a cyanobacterium. J Biol Eng. 2014;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oehler S, Amouyal M, Kolkhof P, von Wilcken-Bergmann B, Muller-Hill B. Quality and position of the three lac operators of E. coli define efficiency of repression. EMBO J. 1994;13:3348–3355. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadler JR, Sasmor H, Betz JL. A perfectly symmetric lac operator binds the lac repressor very tightly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6785–6789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang HH, Camsund D, Lindblad P, Heidorn T. Design and characterization of molecular tools for a Synthetic Biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2577–2593. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thanbichler M, Iniesta AA, Shapiro L. A comprehensive set of plasmids for vanillate- and xylose-inducible gene expression in Caulobacter crescentus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaczmarczyk A, Vorholt JA, Francez-Charlot A. Synthetic vanillate-regulated promoter for graded gene expression in Sphingomonas. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6453. doi: 10.1038/srep06453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morabbi Heravi K, Lange J, Watzlawick H, Kalinowski J, Altenbuchner J. Transcriptional regulation of the vanillate utilization genes (vanABK operon) of Corynebacterium glutamicum by VanR, a PadR-like repressor. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:959–972. doi: 10.1128/JB.02431-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Topp S, Reynoso CM, Seeliger JC, Goldlust IS, Desai SK, Murat D, Shen A, Puri AW, Komeili A, Bertozzi CR, Scott JR, Gallivan JP. Synthetic riboswitches that induce gene expression in diverse bacterial species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:7881–7884. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01537-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topp S, Gallivan JP. Emerging applications of riboswitches in chemical biology. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:139–148. doi: 10.1021/cb900278x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakahira Y, Ogawa A, Asano H, Oyama T, Tozawa Y. Theophylline-dependent riboswitch as a novel genetic tool for strict regulation of protein expression in cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1724–1735. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma AT, Schmidt CM, Golden JW. Regulation of gene expression in diverse cyanobacterial species by using theophylline-responsive riboswitches. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:6704–6713. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01697-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clerico EM, Ditty JL, Golden SS. Specialized techniques for site-directed mutagenesis in cyanobacteria. Met Mol Biol. 2007;362:155–171. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-257-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niederholtmeyer H, Wolfstadter BT, Savage DF, Silver PA, Way JC. Engineering cyanobacteria to synthesize and export hydrophilic products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3462–3466. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00202-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chabot JR, Pedraza JM, Luitel P, van Oudenaarden A. Stochastic gene expression out-of-steady-state in the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Nature. 2007;450:1249–1252. doi: 10.1038/nature06395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szwedziak P, Wang Q, Bharat TA, Tsim M, Lowe J. Architecture of the ring formed by the tubulin homologue FtsZ in bacterial cell division. Elife. 2014;3:e04601. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyagishima SY, Wolk CP, Osteryoung KW. Identification of cyanobacterial cell division genes by comparative and mutational analyses. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:126–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin BE, Wetmore KM, Price MN, Diamond S, Shultzaberger RK, Lowe LC, Curtin G, Arkin AP, Deutschbauer A, Golden SS. The essential gene set of a photosynthetic organism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E6634–6643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519220112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori T, Johnson CH. Independence of circadian timing from cell division in cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2439–2444. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2439-2444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen SE, Erb ML, Pogliano J, Golden SS. Best practices for fluorescence microscopy of the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Meth Enzymol. 2015;551:211–221. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zess EK, Begemann MB, Pfleger BF. Construction of new synthetic biology tools for the control of gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. Biotech Bioeng. 2016;113:424–432. doi: 10.1002/bit.25713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taton A, Unglaub F, Wright NE, Zeng WY, Paz-Yepes J, Brahamsha B, Palenik B, Peterson TC, Haerizadeh F, Golden SS, Golden JW. Broad-host-range vector system for synthetic biology and biotechnology in cyanobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e136. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taton A, Lis E, Adin DM, Dong G, Cookson S, Kay SA, Golden SS, Golden JW. Gene transfer in Leptolyngbya sp. strain BL0902, a cyanobacterium suitable for production of biomass and bioproducts. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elhai J, Vepritskiy A, Muro-Pastor AM, Flores E, Wolk CP. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1998-2005.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.