Abstract

Antibiotic lethality is a complex physiological process, sensitive to external cues. Recent advances using systems approaches have revealed how events downstream of primary target inhibition actively participate in antibiotic death processes. In particular, altered metabolism, translational stress and DNA damage each contribute to antibiotic-induced cell death. Moreover, environmental factors such as oxygen availability, extracellular metabolites, population heterogeneity and multidrug contexts alter antibiotic efficacy by impacting bacterial metabolism and stress responses. Here we review recent studies on antibiotic efficacy and highlight insights gained on the involvement of cellular respiration, redox stress and altered metabolism in antibiotic lethality. We discuss the complexity found in natural environments and highlight knowledge gaps in antibiotic lethality that may be addressed using systems approaches.

Introduction

The discovery of antibiotics early in the 20th century transformed medical practice and microbiological investigation, driving discovery in numerous aspects of microbial physiology including stress responses, mutagenesis and microbial ecology. The primary targets and mechanisms of action for most bactericidal antibiotics have been identified and well-studied [1]; however, there is a growing appreciation that antibiotic lethality is a complex systems-level process that is sensitive to environmental factors [2]. Environmental differences elicit diverse antibiotic treatment responses, from increased susceptibility to phenotypic tolerance. In light of the diminishing pipeline for antibiotic discovery [3], there is an urgent need to better understand mechanisms and factors that influence antibiotic efficacy.

Here, we review recent studies of antibiotic lethality in diverse microbial species. We summarize intracellular mechanisms underlying lethality and describe environmental factors that tune efficacy. We discuss how antibiotics do more than inhibit their primary targets, describe how downstream processes critically participate in active death processes, and highlight insights gained from manipulating extracellular conditions. We also consider the complexity of natural environments and discuss how systems approaches and emerging technologies may provide novel insights into antibiotic lethality.

Bactericidal Processes

Bactericidal antibiotics primarily target processes essential to cellular replication, but studies from several laboratories implicate events downstream of target inhibition as critical components of lethality (Figure 1). This is supported by sequenced strains from experimental evolution studies [4-7] and clinical isolates [8-10] demonstrating that mutations unrelated to an antibiotic target or transport can significantly inhibit antibiotic lethality. In 2007, Kohanski, et al. introduced the hypothesis that bactericidal antibiotics of different classes commonly induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) as part of their lethality [11]. Informed by microarray experiments with E. coli cells treated with diverse bactericidal antibiotics, the authors genetically validated ROS-mediated contributions to lethality by tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity, Fe-S cluster biosynthesis, and SOS-mediated DNA repair. This stimulated further studies revealing the involvement of two-component signaling [12], iron homeostasis [13-15], and nucleotide oxidation [16,17] in ROS-mediated antibiotic lethality; enhanced lethality in cells deficient in oxidative defenses [18]; protection against lethality by mechanisms involving antioxidant defense [19-23]; as well as investigations challenging the general hypothesis [24-26]. These studies have been reviewed and addressed elsewhere [2,27,28].

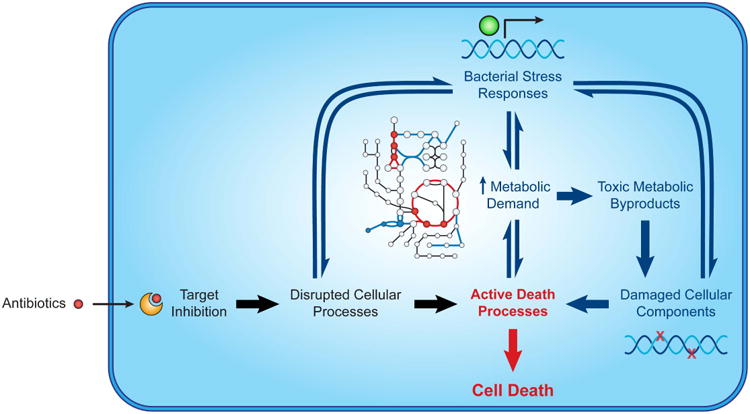

Figure 1.

Antibiotics induce active death processes underlying lethality. Target inhibition directly triggers lethality by disrupting essential cellular processes (black). Stress responses induced by such disruptions indirectly trigger lethality by increasing metabolic demand and generating metabolic byproducts that damage cellular components (e.g., DNA, proteins, lipids) (blue). Environmental factors tune antibiotic lethality by acting on stress responses and/or altering bacterial metabolism.

These investigations and several others demonstrate that antibiotics perturb diverse aspects of bacterial physiology. Such perturbations actively contribute to cell death, in part, by directly inducing cellular damage while also driving the bacterial cell away from homeostasis and inhibiting its ability to cope with antibiotic challenge. Studies on these perturbations have revealed several additional important insights linking aspects of cellular physiology to antibiotic lethality.

Altered Metabolism and Reactive Oxygen Species

Several recent studies have further explored and confirmed the involvement of altered metabolism and ROS in antibiotic lethality using new technologies. Targeted metabolomic studies have revealed significant changes in intracellular energy metabolites following antibiotic treatment [29-31], corroborated by live-cell imaging experiments directly measuring transient changes in ATP [32]. Experiments using the Seahorse XF Analyzer have captured real-time increases to cellular respiration by bactericidal antibiotics [33-35], complementing real-time measurements of overflow ROS production using electrochemical [36] or genetically encoded biosensors [33]. Interestingly, integrated analyses of transcriptomic and metabolomic data have revealed TCA cycle activity to be critical for antibiotic lethality, independent from drug uptake [37]. Collectively, these studies, and several others [8,38-45], demonstrate that changes to bacterial metabolism participate in lethality for many bactericidal antibiotics.

Bacteria are naturally optimized for energy efficiency [46,47] and several recent studies suggest metabolic deregulation may also contribute to antibiotic death processes. For instance, penicillin-binding protein disruption by β-lactams stimulates a futile cycle of cell wall synthesis and degradation that depletes cellular resources as part of its toxicity [48,49]. In addition, ATP synthase inhibition by bedaquiline stimulates futile cycling of protons in the respiratory chain [50], which increases oxygen consumption [35] and is lethal to M. tuberculosis [51]. Moreover, genetically induced futile cycling in MazF-mediated RNA degradation has been shown to confer complete protection against β-lactam and quinolone lethality, but potentiate sensitivity to aminoglycosides [52]. It is likely that metabolic deregulation by futile cycling constitutes a common mechanism of antibiotic lethality. This is supported by recent evidence that genetically induced futile cycling shares many metabolic features with treatment by bactericidal antibiotics, including increased oxygen consumption, increased ROS production and net decreases in intracellular ATP [53]. Interestingly, cells subjected to genetically induced futile cycling also exhibit increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Metabolic deregulation may therefore amplify antibiotic-induced stress and enhance lethality.

Translational Stress

Antibiotic lethality is well recognized to decrease under conditions with reduced bacterial growth, and several recent proteomic studies have revealed ribosomal biosynthesis and activity to be key regulators of bacterial growth rate and metabolism [47,54,55]. Macromolecular processes such as protein translation are therefore also likely to be involved in antibiotic lethality. In support of this, bacteriostatic inhibitors of protein translation suppress the lethality of bactericidal antibiotics in wildtype E. coli [34], but induce lethality in mutant cells depleted for ribosomal assembly operons [56]. Additionally, bactericidal antibiotics induce several heat shock genes responsive to translational stress [11]. Because growing cells devote >50% of their energy to support the demands of protein translation [57], translational stress likely amplifies the lethal consequences of metabolic stresses induced by antibiotic treatment. Future studies are needed to clarify how antibiotic disruption of translation and other macromolecular processes contributes to lethality.

DNA Damage

Several DNA repair genes are enriched in chemogenomic screens [58,59] and promoter-reporter experiments [60], suggesting DNA damage to also be critical for antibiotic lethality. These findings have been supported genetically, as deletion of SOS response genes enhances drug susceptibility [11,16], while over-expression of mismatch repair genes confers protection [16,33]. Moreover, biochemical inhibition of RecA with polysulfonated compounds potentiates the lethality of multiple antibiotics against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [61,62]. Oxidative damage to the nucleotide pool may, in part, underlie this phenotype [29], as incorporation of 8-oxo-guanine induces mismatch repair defects that trigger the formation of double-stranded DNA breaks [16]. Additionally, holliday junction resolvase disruption was recently shown to enhance quinolone lethality in mycobacteria [63]. This could be rescued by treatment with bipyridyl, an iron chelator, and thiourea, a hydroxyl radical chelator, supporting prior work implicating antibiotic-induced oxidative stress in damaging DNA [11,16]. Mechanistic studies are needed to further clarify the processes bridging antibiotic target inhibition and lethal DNA damage.

Primary and Secondary Death Processes

Collectively, these studies implicate events downstream of target inhibition as active participants in antibiotic lethality. It is our view that much of the misunderstanding over antibiotic lethality is derived from the difficulty in experimentally separating the lethal contributions of essential gene product inhibition from those of downstream mechanisms. It may be possible to distinguish between these biochemically, as the lethality driven by secondary processes can be interrupted by inhibiting protein translation and cell respiration [34] or by metabolic shunting [37]. Cell death emerging from stress-induced death processes was recently studied in an antibiotic-free system using a historically significant fusion protein [64]. The authors demonstrated that the primary consequence of jamming the SecY protein translocation machinery was cell stasis and that cell death instead emerged from downstream events shared with antibiotic lethality, including ROS accumulation and double-stranded DNA damage. Importantly, nucleotide oxidation occurred hours before cell death in this system. Taken together, these studies support a model for antibiotic lethality where target inhibition drives active death processes by (1) damaging essential cellular processes and (2) inducing stress responses that increase metabolic activity, thereby generating toxic metabolic byproducts, that damage cellular components (Figure 1).

Environmental Factors

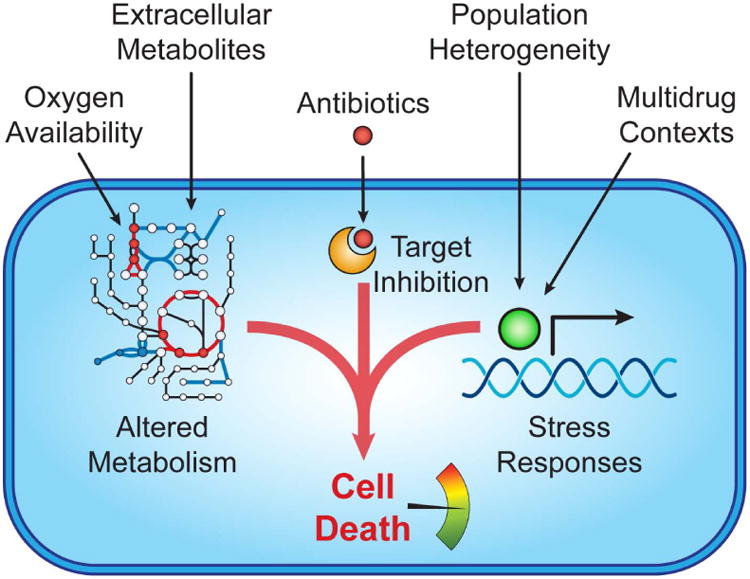

Bacterial stress responses evolved to help bacteria adapt to various environments [65] and may confer protection against antibiotic lethality. For instance, pre-treatment with hydrogen peroxide can protect against multiple bactericidal antibiotics by priming oxidative stress responses [33], and nutrient starvation can induce phenotypically tolerant ‘persister’ cells by activating ppGpp and the stringent response [66,67]. Several recent studies demonstrate how environmental factors may alter antibiotic efficacy, providing additional insight into antibiotic lethality (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Environmental factors tune antibiotic lethality. Cues such as oxygen availability and extracellular metabolites impact cell death by acting on cell metabolism. Population heterogeneity and multidrug contexts protect against lethality by inducing stress responses and defense mechanisms.

Oxygen Availability

Antibiotic efficacy decreases in the absence of oxygen [24,25,33] and hyperbaric oxygen can potentiate antibiotic killing of bacterial biofilms [68]. Under normoxia, oxygen participates in aerobic respiration as the terminal electron acceptor for ATP synthesis and produces reactive species as metabolic byproducts [35]. In such conditions, antibiotic efficacy is linked to respiratory activity; for example, deletion of the cytochrome oxidases, which reduces respiration, inhibits drug lethality [34], while deletion of ATP synthase subunits, which increases respiration, enhances lethality [34,69]. Similarly, respiratory suppression by nitrite also inhibits antibiotic killing [70]. Under anoxia, nitrate frequently participates in anaerobic respiration as the terminal electron acceptor and can potentiate antibiotic killing [33]; it is not yet known if nitrate and other terminal electron acceptors also generate toxic metabolic byproducts that contribute to antibiotic death processes. Cellular respiration likely affects antibiotic efficacy due to its roles in metabolism and energy production, but may also contribute to lethality by facilitating drug import [37,71] or stimulating intracellular alkalization [72]. Collectively, these studies implicate respiratory activity as an important mediator of the lethal processes induced by antibiotics.

Extracellular Metabolites

Environmental nutrients affect many aspects of bacterial physiology that alter antibiotic efficacy, including growth kinetics and stress response activation [73,74]. Recent studies using flow cytometry and high-throughput assays have revealed how specific carbon metabolites or amino acids may enhance antibiotic death processes by fueling TCA cycle activity, increasing cellular respiration and inducing a proton motive force, promoting both drug uptake and subsequent lethality [37,71,75,76]. Interestingly, flux through the glyoxylate shunt was shown to suppress aminoglycoside potentiation by metabolites such as fumarate despite measureable drug uptake, implicating an active metabolic component to antibiotic lethality [37]. This is supported by recent chemogenetic screens revealing collateral antibiotic sensitivity under nutrient limitation [77]. Additionally, cysteine supplementation was shown to increase cellular respiration, ROS, and antibiotic lethality, as well as inhibit persister formation in Mycobacterium [78] through thiol-mediated redox stress [79,80]. To date, input-output relationships between environmental metabolites and antibiotic death phenotypes have not been systematically mapped; such efforts will be important for identifying specific metabolic pathways participating in antibiotic lethality.

Population Heterogeneity

Antibiotic treatment and environmental stresses can give rise to population heterogeneity and confer phenotypic protection against lethality [81]; simple examples include variable expression of multi-drug efflux pumps [82] and stochastic formation of persister cells by toxin-antitoxin systems and the ppGpp-mediated stringent response [83,84]. Recent studies have revealed several additional persister mechanisms, including ATP depletion [85,86], morphological differentiation [87], inter-cell signaling [88,89], and toxin-antitoxin-mediated inhibition of proton-motive force [90,91] or protein translation [92]. Microbial ecologists have largely viewed population heterogeneity as a form of bet-hedging, conserved to facilitate the adaptation to new environments [93]. In support of this, several studies demonstrate how persister mechanisms can help pathogens survive inside host cells [94,95] and provide a reservoir for evolving antibiotic resistance [96-98]. Investigations have also shown how social behaviors such as quorum sensing [99], signaling [100] and cooperative mutualism [101] can confer protection against antibiotic lethality in mixed-species environments. Nascent studies on population-level responses to antibiotic treatment have revealed several intra- and inter-species mechanisms for collective protection [102,103], but such experiments are challenging due to scale. Advances in synthetic biology and microfluidic technologies are now poised to enable significant insight into ecological mechanisms participating in antibiotic efficacy.

Multidrug Contexts

Antibiotic treatment outcomes are diverse in multidrug environments, and previous exposure to an antibiotic can alter the efficacy of other antibiotics [104]. Studies on multidrug contexts highlight the roles of cellular respiration [34], ATP synthesis and polysaccharide synthesis [69] in determining treatment efficacy. Pretreatment with sub-lethal doses of single antibiotics induces physiological stress responses that protect against antibiotic lethality [60] and other environmental stresses [105]. Extended antibiotic exposure leads to genetically encoded resistance with collateral sensitivity or resistance to antibiotics of different classes [106], which may be exploited to potentiate population-level lethality by antibiotic cycling [107,108]. Recent efforts integrating metabolomic profiling with experimental evolution have revealed how bacterial metabolism may constrain the acquisition of antibiotic resistance and differential cross-resistance [109]. Mechanistic details explaining antibiotic synergy and antagonism remain nascent; future studies on multidrug efficacy and resistance would benefit from integrated exploration of environmental and physiological factors.

Perspectives

Although antibiotics are routinely studied under well-controlled lab conditions, the natural environments in which antibiotics are typically found and used are complex in nutrient availability, microbial heterogeneity, and other external stressors. Because environmental factors can elicit diverse effects on antibiotic lethality, careful consideration must be paid to experimental conditions to minimize confounding effects by contextual elements. Several open questions remain with respect to antibiotic lethality in natural contexts, including antibiotic-induced changes to the extracellular environment and the dynamic interactions between different species sharing a common ecological niche. Moreover, understanding the differences in microbial physiology between host metabolic environments and the nutrient rich conditions commonly used to study bacterial pathogens will be important for translating in vitro discoveries into clinical care. Further understanding on how external effectors act on bactericidal processes will require systems approaches to meet the challenges posed by such complexity.

Antibiotic lethality is increasingly understood to be driven by active death processes resulting from both target inhibition and subsequent induction of stress responses. Compensatory changes to bacterial physiology likely participate bi-directionally, furthering downstream cellular damage and modulating the direct upstream consequences of target inhibition. For instance, alterations in cellular metabolism or protein translation may have far-reaching consequences on target availability and the biochemistry of drug-target interactions. Future studies are needed to clarify the relative contributions of primary and secondary death processes.

Recent advances in experimental technologies and quantitative modeling are now poised to enable additional systems-level insights into antibiotic lethality. Mass spectrometry allows interrogation into spatial determinants of antibiotic efficacy [110,111] and synthetic biology has contributed novel tools for perturbing essential genes [112]. Current quantitative models are providing mechanistic insights into several nonlinear components of antibiotic lethality [56,113] and are useful for predicting multidrug treatment outcomes [114,115] and antibiotic drug synergies [116,117]. Integration of these tools will enable identification of additional mechanistic details between primary target inhibition and subsequent lethality.

Conclusion

Antibiotics naturally evolved as inhibitory agents for microbial warfare and have provided insights into mechanisms underlying bacterial cell death. Recent studies have revealed that several events downstream of primary target inhibition actively contribute to antibiotic lethality, including alterations to cellular metabolism, protein translation, and DNA damage. These processes are sensitive to environmental cues and future studies will be needed to better understand antibiotic efficacy in natural settings. Systems approaches have the potential to accelerate such efforts and provide additional mechanistic insight into antibiotic lethality.

Highlights.

Antibiotic lethality involves processes downstream of primary target inhibition.

Respiration and altered metabolism actively participate in antibiotic lethality.

Environmental cues alter antibiotic efficacy via metabolism and stress responses.

Systems approaches are important for studying antibiotics in complex environments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers K99GM118907 and U19AI111276, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under award number 1122374, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency under award number HDTRA1-15-1-0051, and a generous gift from Anita and Josh Bekenstein.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: J.J.C. is scientific co-founder and SAB chair of EnBiotix, an antibiotics startup company.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:423–435. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ, Walker GC. Unraveling the physiological complexities of antibiotic lethality. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:313–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown ED, Wright GD. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fridman O, Goldberg A, Ronin I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ. Optimization of lag time underlies antibiotic tolerance in evolved bacterial populations. Nature. 2014;513:418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Bergh B, Michiels JE, Michiels J. Experimental Evolution of Escherichia coli Persister Levels Using Cyclic Antibiotic Treatments. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1333:131–143. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2854-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez JE, Kaufmann-Malaga BB, Wivagg CN, Kim PB, Silvis MR, Renedo N, Ioerger TR, Ahmad R, Livny J, Fishbein S, et al. Ribosomal mutations promote the evolution of antibiotic resistance in a multidrug environment. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.20420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohanski MA, DePristo MA, Collins JJ. Sublethal antibiotic treatment leads to multidrug resistance via radical-induced mutagenesis. Mol Cell. 2010;37:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen D, Joshi-Datar A, Lepine F, Bauerle E, Olakanmi O, Beer K, McKay G, Siehnel R, Schafhauser J, Wang Y, et al. Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science. 2011;334:982–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1211037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rueda J, Realpe T, Mejia GI, Zapata E, Rozo JC, Ferro BE, Robledo J. Genotypic Analysis of Genes Associated with Independent Resistance and Cross-Resistance to Isoniazid and Ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Clinical Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7805–7810. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01028-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia B, Raphenya AR, Alcock B, Waglechner N, Guo P, Tsang KK, Lago BA, Dave BM, Pereira S, Sharma AN, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D566–D573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Wierzbowski J, Cottarel G, Collins JJ. Mistranslation of membrane proteins and two-component system activation trigger antibiotic-mediated cell death. Cell. 2008;135:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeom J, Imlay JA, Park W. Iron homeostasis affects antibiotic-mediated cell death in Pseudomonas species. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22689–22695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frawley ER, Crouch ML, Bingham-Ramos LK, Robbins HF, Wang W, Wright GD, Fang FC. Iron and citrate export by a major facilitator superfamily pump regulates metabolism and stress resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12054–12059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218274110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehi O, Bogos B, Csorgo B, Pal F, Nyerges A, Papp B, Pal C. Perturbation of iron homeostasis promotes the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:2793–2804. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foti JJ, Devadoss B, Winkler JA, Collins JJ, Walker GC. Oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool underlies cell death by bactericidal antibiotics. Science. 2012;336:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1219192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kottur J, Nair DT. Reactive Oxygen Species Play an Important Role in the Bactericidal Activity of Quinolone Antibiotics. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:2397–2400. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bizzini A, Zhao C, Auffray Y, Hartke A. The Enterococcus faecalis superoxide dismutase is essential for its tolerance to vancomycin and penicillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:1196–1202. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gusarov I, Shatalin K, Starodubtseva M, Nudler E. Endogenous nitric oxide protects bacteria against a wide spectrum of antibiotics. Science. 2009;325:1380–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1175439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Zhao X, Malik M, Drlica K. Contribution of reactive oxygen species to pathways of quinolone-mediated bacterial cell death. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:520–524. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shatalin K, Shatalina E, Mironov A, Nudler E. H2S: a universal defense against antibiotics in bacteria. Science. 2011;334:986–990. doi: 10.1126/science.1209855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling J, Cho C, Guo LT, Aerni HR, Rinehart J, Soll D. Protein aggregation caused by aminoglycoside action is prevented by a hydrogen peroxide scavenger. Mol Cell. 2012;48:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosel M, Li L, Drlica K, Zhao X. Superoxide-mediated protection of Escherichia coli from antimicrobials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5755–5759. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00754-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Imlay JA. Cell death from antibiotics without the involvement of reactive oxygen species. Science. 2013;339:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1232751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keren I, Wu Y, Inocencio J, Mulcahy LR, Lewis K. Killing by bactericidal antibiotics does not depend on reactive oxygen species. Science. 2013;339:1213–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1232688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ezraty B, Vergnes A, Banzhaf M, Duverger Y, Huguenot A, Brochado AR, Su SY, Espinosa L, Loiseau L, Py B, et al. Fe-S cluster biosynthesis controls uptake of aminoglycosides in a ROS-less death pathway. Science. 2013;340:1583–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1238328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Acker H, Coenye T. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Antibiotic-Mediated Killing of Bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X, Hong Y, Drlica K. Moving forward with reactive oxygen species involvement in antimicrobial lethality. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:639–642. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belenky P, Ye JD, Porter CB, Cohen NR, Lobritz MA, Ferrante T, Jain S, Korry BJ, Schwarz EG, Walker GC, et al. Bactericidal Antibiotics Induce Toxic Metabolic Perturbations that Lead to Cellular Damage. Cell Rep. 2015;13:968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoerr V, Duggan GE, Zbytnuik L, Poon KK, Grosse C, Neugebauer U, Methling K, Loffler B, Vogel HJ. Characterization and prediction of the mechanism of action of antibiotics through NMR metabolomics. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:82. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0696-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zampieri M, Zimmermann M, Claassen M, Sauer U. Nontargeted Metabolomics Reveals the Multilevel Response to Antibiotic Perturbations. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1214–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maglica Z, Ozdemir E, McKinney JD. Single-cell tracking reveals antibiotic-induced changes in mycobacterial energy metabolism. MBio. 2015;6:e02236–02214. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02236-14. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that antibiotic treatment significantly alters single-cell energy production using microfluidics and an intracellular ATP biosensor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dwyer DJ, Belenky PA, Yang JH, MacDonald IC, Martell JD, Takahashi N, Chan CT, Lobritz MA, Braff D, Schwarz EG, et al. Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2100–2109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401876111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobritz MA, Belenky P, Porter CB, Gutierrez A, Yang JH, Schwarz EG, Dwyer DJ, Khalil AS, Collins JJ. Antibiotic efficacy is linked to bacterial cellular respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:8173–8180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509743112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamprecht DA, Finin PM, Rahman MA, Cumming BM, Russell SL, Jonnala SR, Adamson JH, Steyn AJ. Turning the respiratory flexibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis against itself. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12393. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X, Marrakchi M, Jahne M, Rogers S, Andreescu S. Real-time investigation of antibiotics-induced oxidative stress and superoxide release in bacteria using an electrochemical biosensor. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;91:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meylan S, Porter CB, Yang JH, Belenky P, Gutierrez A, Lobritz MA, Park J, Kim SH, Moskowitz SM, Collins JJ. Carbon Sources Tune Antibiotic Susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Control. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nandakumar M, Nathan C, Rhee KY. Isocitrate lyase mediates broad antibiotic tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4306. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vilcheze C, Hartman T, Weinrick B, Jacobs WR., Jr Mycobacterium tuberculosis is extraordinarily sensitive to killing by a vitamin C-induced Fenton reaction. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1881. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas VC, Kinkead LC, Janssen A, Schaeffer CR, Woods KM, Lindgren JK, Peaster JM, Chaudhari SS, Sadykov M, Jones J, et al. A dysfunctional tricarboxylic acid cycle enhances fitness of Staphylococcus epidermidis during beta-lactam stress. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00437-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brynildsen MP, Winkler JA, Spina CS, MacDonald IC, Collins JJ. Potentiating antibacterial activity by predictably enhancing endogenous microbial ROS production. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:160–165. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant SS, Kaufmann BB, Chand NS, Haseley N, Hung DT. Eradication of bacterial persisters with antibiotic-generated hydroxyl radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12147–12152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203735109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tkachenko AG, Akhova AV, Shumkov MS, Nesterova LY. Polyamines reduce oxidative stress in Escherichia coli cells exposed to bactericidal antibiotics. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duan X, Huang X, Wang X, Yan S, Guo S, Abdalla AE, Huang C, Xie J. l-Serine potentiates fluoroquinolone activity against Escherichia coli by enhancing endogenous reactive oxygen species production. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:2192–2199. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goswami M, Mangoli SH, Jawali N. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:949–954. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.949-954.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maitra A, Dill KA. Bacterial growth laws reflect the evolutionary importance of energy efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:406–411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421138111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hui S, Silverman JM, Chen SS, Erickson DW, Basan M, Wang J, Hwa T, Williamson JR. Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals a simple strategy of global resource allocation in bacteria. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:784. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho H, Uehara T, Bernhardt TG. Beta-lactam antibiotics induce a lethal malfunctioning of the bacterial cell wall synthesis machinery. Cell. 2014;159:1300–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho H, Wivagg CN, Kapoor M, Barry Z, Rohs PD, Suh H, Marto JA, Garner EC, Bernhardt TG. Bacterial cell wall biogenesis is mediated by SEDS and PBP polymerase families functioning semi-autonomously. Nat Microbiol. 2016:16172. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.172. ■ Of special interest. ■ These papers [42,43] demonstrated futile cycling of peptidoglycan precursors in response to different (β-lactam antibiotics, carefully applying antibiotics to probe aspects of cell physiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hards K, Robson JR, Berney M, Shaw L, Bald D, Koul A, Andries K, Cook GM. Bactericidal mode of action of bedaquiline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2028–2037. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao SP, Alonso S, Rand L, Dick T, Pethe K. The protonmotive force is required for maintaining ATP homeostasis and viability of hypoxic, nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11945–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mok WW, Park JO, Rabinowitz JD, Brynildsen MP. RNA Futile Cycling in Model Persisters Derived from MazF Accumulation. MBio. 2015;6:e01588–01515. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01588-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adolfsen KJ, Brynildsen MP. Futile cycling increases sensitivity toward oxidative stress in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2015;29:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.02.006. ■ Of outstanding interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that metabolic futile cycling increases oxygen consumption and ROS production and decreases intracellular ATP. The net result is an intracellular phenotype similar to antibiotic-treated cells that exhibits increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott M, Klumpp S, Mateescu EM, Hwa T. Emergence of robust growth laws from optimal regulation of ribosome synthesis. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:747. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basan M, Hui S, Okano H, Zhang Z, Shen Y, Williamson JR, Hwa T. Overflow metabolism in Escherichia coli results from efficient proteome allocation. Nature. 2015;528:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature15765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levin BR, McCall IC, Perrot V, Weiss H, Ovesepian A, Baquero F. A Numbers Game: Ribosome Densities, Bacterial Growth, and Antibiotic-Mediated Stasis and Death. MBio. 2017:8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02253-16. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that antibiotic lethality is associated with the number of functional ribosomal units for antibiotics inhibiting protein translation and that bacteriostatic antibiotics can be lethal in bacteria depleted for ribosomal operons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russell JB, Cook GM. Energetics of bacterial growth: balance of anabolic and catabolic reactions. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:48–62. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.48-62.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu A, Tran L, Becket E, Lee K, Chinn L, Park E, Tran K, Miller JH. Antibiotic sensitivity profiles determined with an Escherichia coli gene knockout collection: generating an antibiotic bar code. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00906-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nichols RJ, Sen S, Choo YJ, Beltrao P, Zietek M, Chaba R, Lee S, Kazmierczak KM, Lee KJ, Wong A, et al. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell. 2011;144:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathieu A, Fleurier S, Frenoy A, Dairou J, Bredeche MF, Sanchez-Vizuete P, Song X, Matic I. Discovery and Function of a General Core Hormetic Stress Response in E. coli Induced by Sublethal Concentrations of Antibiotics. Cell Rep. 2016;17:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.001. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that sublethal treatment with antibiotics of diverse classes induce a common, general stress response that increases metabolism and alters macromolecular physiological processes using a gene promoter-reporter system. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alam MK, Alhhazmi A, DeCoteau JF, Luo Y, Geyer CR. RecA Inhibitors Potentiate Antibiotic Activity and Block Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nautiyal A, Patil KN, Muniyappa K. Suramin is a potent and selective inhibitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RecA protein and the SOS response: RecA as a potential target for antibacterial drug discovery. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1834–1843. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Long Q, Du Q, Fu T, Drlica K, Zhao X, Xie J. Involvement of Holliday junction resolvase in fluoroquinolone-mediated killing of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1782–1785. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04434-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takahashi N, Gruber CC, Yang JH, Liu X, Braff D, Yashaswini C, Bhubhani S, Furuta Y, Andreescu S, Collins JJ, et al. Lethality of MalE-LacZ hybrid protein shares mechanistic attributes with oxidative component of antibiotic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707466114. published ahead of print August 9, 2017. ■ This paper investigates active death processes following stress response induction in an antibiotic-free system using a historically important fusion protein that shares several hallmarks with antibiotic lethality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Storz G, Hengge R. Bacterial stress responses. 2nd. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2011. American Society for Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amato SM, Brynildsen MP. Persister Heterogeneity Arising from a Single Metabolic Stress. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2090–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radzikowski JL, Vedelaar S, Siegel D, Ortega AD, Schmidt A, Heinemann M. Bacterial persistence is an active sigmaS stress response to metabolic flux limitation. Mol Syst Biol. 2016;12:882. doi: 10.15252/msb.20166998. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper integrated proteomic and metabolomic approaches to characterize persister phenotypes induced by nutrient transitions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kolpen M, Mousavi N, Sams T, Bjarnsholt T, Ciofu O, Moser C, Kuhl M, Hoiby N, Jensen PO. Reinforcement of the bactericidal effect of ciprofloxacin on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm by hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chevereau G, Bollenbach T. Systematic discovery of drug interaction mechanisms. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:807. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156098. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper modeled the expected growth rate of E. coli single gene deletion mutants challenged with antibiotic combinations to identify genes and corresponding cellular functions involved in drug interactions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zemke AC, Kocak BR, Bomberger JM. Sodium Nitrite Inhibits Killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms by Ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00448-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allison KR, Brynildsen MP, Collins JJ. Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature. 2011;473:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bartek IL, Reichlen MJ, Honaker RW, Leistikow RL, Clambey ET, Scobey MS, Hinds AB, Born SE, Covey CR, Schurr MJ, et al. Antibiotic Bactericidal Activity Is Countered by Maintaining pH Homeostasis in Mycobacterium smegmatis. mSphere. 2016;1 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00176-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Varik V, Oliveira SR, Hauryliuk V, Tenson T. Composition of the outgrowth medium modulates wake-up kinetics and ampicillin sensitivity of stringent and relaxed Escherichia coli. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22308. doi: 10.1038/srep22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bailey AM, Webber MA, Piddock LJ. Medium plays a role in determining expression of acrB, marA, and soxS in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1071–1074. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.1071-1074.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peng B, Su YB, Li H, Han Y, Guo C, Tian YM, Peng XX. Exogenous alanine and/or glucose plus kanamycin kills antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Cell Metab. 2015;21:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shan Y, Lazinski D, Rowe S, Camilli A, Lewis K. Genetic basis of persister tolerance to aminoglycosides in Escherichia coli. MBio. 2015;6 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cote JP, French S, Gehrke SS, MacNair CR, Mangat CS, Bharat A, Brown ED. The Genome-Wide Interaction Network of Nutrient Stress Genes in Escherichia coli. MBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01714-16. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that nutrient stress can yield synthetic lethal interactions with several metabolic processes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vilcheze C, Hartman T, Weinrick B, Jain P, Weisbrod TR, Leung LW, Freundlich JS, Jacobs WR., Jr Enhanced respiration prevents drug tolerance and drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704376114. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that metabolic amino acid supplementation may prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistance in M tuberculosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park S, Imlay JA. High levels of intracellular cysteine promote oxidative DNA damage by driving the fenton reaction. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1942–1950. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1942-1950.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hartman T, Weinrick B, Vilcheze C, Berney M, Tufariello J, Cook GM, Jacobs WR., Jr Succinate dehydrogenase is the regulator of respiration in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004510. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brauner A, Fridman O, Gefen O, Balaban NQ. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:320–330. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pu Y, Zhao Z, Li Y, Zou J, Ma Q, Zhao Y, Ke Y, Zhu Y, Chen H, Baker MA, et al. Enhanced Efflux Activity Facilitates Drug Tolerance in Dormant Bacterial Cells. Mol Cell. 2016;62:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harms A, Maisonneuve E, Gerdes K. Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science. 2016;354 doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4268. ■ This is a good recent review on mechanisms of persister formation involving toxin-antitoxin systems and the stringent response. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cohen NR, Lobritz MA, Collins JJ. Microbial persistence and the road to drug resistance. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:632–642. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shan Y, Brown Gandt A, Rowe SE, Deisinger JP, Conlon BP, Lewis K. ATP-Dependent Persister Formation in Escherichia coli. MBio. 2017;8 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02267-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Conlon BP, Rowe SE, Gandt AB, Nuxoll AS, Donegan NP, Zalis EA, Clair G, Adkins JN, Cheung AL, Lewis K. Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16051. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.51. ■ These two papers [85,86] demonstrate that the formation of persister cells can be independent of toxin-antitoxin induction and depends on intracellular ATP levels. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu ML, Gengenbacher M, Dick T. Mild Nutrient Starvation Triggers the Development of a Small-Cell Survival Morphotype in Mycobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:947. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vega NM, Allison KR, Khalil AS, Collins JJ. Signaling-mediated bacterial persister formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:431–433. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vega NM, Allison KR, Samuels AN, Klempner MS, Collins JJ. Salmonella typhimurium intercepts Escherichia coli signaling to enhance antibiotic tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14420–14425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308085110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Verstraeten N, Knapen WJ, Kint CI, Liebens V, Van den Bergh B, Dewachter L, Michiels JE, Fu Q, David CC, Fierro AC, et al. Obg and Membrane Depolarization Are Part of a Microbial Bet-Hedging Strategy that Leads to Antibiotic Tolerance. Mol Cell. 2015;59:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dorr T, Vulic M, Lewis K. Ciprofloxacin causes persister formation by inducing the TisB toxin in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maisonneuve E, Castro-Camargo M, Gerdes K. (p)ppGpp controls bacterial persistence by stochastic induction of toxin-antitoxin activity. Cell. 2013;154:1140–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grimbergen AJ, Siebring J, Solopova A, Kuipers OP. Microbial bet-hedging: the power of being different. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;25:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Helaine S, Cheverton AM, Watson KG, Faure LM, Matthews SA, Holden DW. Internalization of Salmonella by macrophages induces formation of nonreplicating persisters. Science. 2014;343:204–208. doi: 10.1126/science.1244705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Manina G, Dhar N, McKinney JD. Stress and host immunity amplify Mycobacterium tuberculosis phenotypic heterogeneity and induce nongrowing metabolically active forms. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Levin-Reisman I, Ronin I, Gefen O, Braniss I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science. 2017;355:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Van den Bergh B, Michiels JE, Wenseleers T, Windels EM, Boer PV, Kestemont D, De Meester L, Verstrepen KJ, Verstraeten N, Fauvart M, et al. Frequency of antibiotic application drives rapid evolutionary adaptation of Escherichia coli persistence. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16020. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Artemova T, Gerardin Y, Dudley C, Vega NM, Gore J. Isolated cell behavior drives the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:822. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Thompson JA, Oliveira RA, Djukovic A, Ubeda C, Xavier KB. Manipulation of the quorum sensing signal AI-2 affects the antibiotic-treated gut microbiota. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1861–1871. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee HH, Molla MN, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Bacterial charity work leads to population- wide resistance. Nature. 2010;467:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature09354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yurtsev EA, Conwill A, Gore J. Oscillatory dynamics in a bacterial cross-protection mutualism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:6236–6241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523317113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meredith HR, Srimani JK, Lee AJ, Lopatkin AJ, You L. Collective antibiotic tolerance: mechanisms, dynamics and intervention. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vega NM, Gore J. Collective antibiotic resistance: mechanisms and implications. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;21:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bollenbach T. Antimicrobial interactions: mechanisms and implications for drug discovery and resistance evolution. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;27:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mitosch K, Rieckh G, Bollenbach T. Noisy Response to Antibiotic Stress Predicts Subsequent Single-Cell Survival in an Acidic Environment. Cell Syst. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.03.001. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper used a promoter-reporter screen to identify a temporal acid stress response to trimethoprim with implications for drug mechanism of action and antibiotic-induced cross-protection against other environmental stressors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pal C, Papp B, Lazar V. Collateral sensitivity of antibiotic-resistant microbes. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kim S, Lieberman TD, Kishony R. Alternating antibiotic treatments constrain evolutionary paths to multidrug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:14494–14499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409800111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Imamovic L, Sommer MO. Use of collateral sensitivity networks to design drug cycling protocols that avoid resistance development. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:204ra132. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zampieri M, Enke T, Chubukov V, Ricci V, Piddock L, Sauer U. Metabolic constraints on the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Mol Syst Biol. 2017;13:917. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167028. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper combined experimental evolution and metabolomics to characterize how metabolic fluxes shape bacterial adaptation to antibiotic stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Prideaux B, Via LE, Zimmerman MD, Eum S, Sarathy J, O'Brien P, Chen C, Kaya F, Weiner DM, Chen PY, et al. The association between sterilizing activity and drug distribution into tuberculosis lesions. Nat Med. 2015;21:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pienaar E, Cilfone NA, Lin PL, Dartois V, Mattila JT, Butler JR, Flynn JL, Kirschner DE, Linderman JJ. A computational tool integrating host immunity with antibiotic dynamics to study tuberculosis treatment. J Theor Biol. 2015;367:166–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.11.021. ■ Of special interest. ■ This paper integrates spatially resolved mass spectrometry data with mathematical models of antibiotic susceptibility to predict treatment outcomes on the complex in vivo environments of M. tuberculosis granulomas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cameron DE, Collins JJ. Tunable protein degradation in bacteria. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1276–1281. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Abel Zur Wiesch P, Abel S, Gkotzis S, Ocampo P, Engelstadter J, Hinkley T, Magnus C, Waldor MK, Udekwu K, Cohen T. Classic reaction kinetics can explain complex patterns of antibiotic action. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:287ra273. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa8760. ■ Of outstanding interest. ■ This paper demonstrates that simple mathematical models can explain several complex features of antibiotic killing dynamics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chandrasekaran S, Cokol-Cakmak M, Sahin N, Yilancioglu K, Kazan H, Collins JJ, Cokol M. Chemogenomics and orthology-based design of antibiotic combination therapies. Mol Syst Biol. 2016;12:872. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156777. ■ This paper applies a machine learning algorthim to chemogenomic screening data topredict outcomes from treatments with antibiotic combinations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wildenhain J, Spitzer M, Dolma S, Jarvik N, White R, Roy M, Griffiths E, Bellows DS, Wright GD, Tyers M. Prediction of Synergism from Chemical-Genetic Interactions by Machine Learning. Cell Syst. 2015;1:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Aziz RK, Monk JM, Lewis RM, In Loh S, Mishra A, Abhay Nagle A, Satyanarayana C, Dhakshinamoorthy S, Luche M, Kitchen DB, et al. Systems biology-guided identification of synthetic lethal gene pairs and its potential use to discover antibiotic combinations. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16025. doi: 10.1038/srep16025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Krueger AS, Munck C, Dantas G, Church GM, Galagan J, Lehar J, Sommer MO. Simulating Serial-Target Antibacterial Drug Synergies Using Flux Balance Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]