Abstract

Current interest in cocrystal development resides in the advantages that the cocrystal may have in solubility and dissolution compared to the parent drug. This work provides a mechanistic analysis and comparison of the dissolution behavior of carbamazepine (CBZ) and its two cocrystals, carbamazepine-saccharin (CBZ-SAC) and carbamazepine-salicylic acid (CBZ-SLC) under the influence of pH and micellar solubilization. A simple mathematical equation is derived based on the mass transport analyses to describe the dissolution advantage of cocrystals. The dissolution advantage is the ratio of the cocrystal flux to drug flux and is defined as the solubility advantage (cocrystal to drug solubility ratio) times the diffusivity advantage (cocrystal to drug diffusivity ratio). In this work, the effective diffusivity of CBZ in the presence of surfactant was determined to be different and less than those of the cocrystals. The higher effective diffusivity of drug from the dissolved cocrystals, the diffusivity advantage, can impart a dissolution advantage to cocrystals with lower solubility than the parent drug while still maintaining thermodynamic stability. Dissolution conditions where cocrystals can display both thermodynamic stability and a dissolution advantage can be obtained from the mass transport models and this information is useful for both cocrystal selection and formulation development.

Keywords: Dissolution, Dissolution Rate, Mathematical Model, Solubility, Co-crystals, Diffusion, Absorption

Introduction

Cocrystallization is one of the powerful strategies used in pharmaceutical development to improve the aqueous solubility of inherently insoluble drugs.1–6 Cocrystallization usually involves the formation of cocrystals through hydrogen bonding between a hydrophobic drug and hydrophilic coformer.7,8 As a new and different solid form, the physicochemical properties of cocrystals need to be fully evaluated in order to develop a feasible formulation. Among these properties, solubility and dissolution are of particular interest due to their importance in determining the oral absorption of drugs.9 A thorough understanding of cocrystal solubility and dissolution mechanisms not only facilitates formulation development, but also provides important insights on their influence on drug oral absorption.

One of the motivations for cocrystal development is the solubility advantage that these cocrystalline materials can generate.1–6 However, the cocrystal solubility advantage is not constant and it varies with solution conditions such as pH and solubilizing agents.10–15 Cocrystals can exhibit higher, equal, or lower solubility compared to the parent drug depending on the solution conditions. Important transition points such as pHmax and critical stabilization concentration (CSC) have been identified to assess the solubility behavior of cocrystals.10,11,15 CSC can be achieved with additives that preferentially solubilize the drug compared to coformer.10,12,13 Cocrystal is thermodynamically unstable below the CSC but thermodynamically stable above the CSC.10,12,13 Without knowing these important concepts, cocrystals may appear to be unpredictable as their dissolution, stability, and bioavailability may vary with their solubility advantage over parent drugs. Consequently, a thorough understanding of the transition point is essential for fine-tuning formulation of cocrystals to achieve the desired cocrystal behavior.

Another question of interest for cocrystal development is whether cocrystals exhibit higher dissolution rate compared to the parent drug. Understanding the dissolution behavior of cocrystals is equally important in formulation development. The dissolution mechanism of cocrystals under the influence of pH and surfactant has been evaluated through the development of mass transport models.16 Mass transport analyses indicate that the physicochemical properties of cocrystals and their components such as solubility product, ionization constants, solubilization constants, and diffusion coefficients, are important parameters for determining the rate of cocrystal dissolution.16 Dissolution rate is directly proportional to cocrystal solubility. This relationship leads to an important question to be addressed in this study: is a cocrystal solubility advantage necessary to obtain higher cocrystal dissolution rate compared to the parent drug?

Here, a simple mathematical model is presented to determine the dissolution advantage of cocrystals compared to the parent drug. This model is evaluated using carbamazepine (CBZ) and two cocrystals with 1:1 stoichiometry, carbamazepine-saccharin (CBZ-SAC) and carbamazepine-salicylic acid (CBZ-SLC). CBZ is non-ionizable and both SAC and SLC are acidic coformers with pKa values of 1.6 and 3.0,1,10 respectively. The stable form of CBZ in aqueous conditions is the dihydrate. To eliminate the complication of conversion, CBZ dihydrate (CBZD) was used in this study. Dissolution of both CBZD and its two cocrystals were determined using a rotating disk apparatus. Dissolution studies refer to constant surface area unless otherwise stated. Both CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC are more soluble than CBZD in the absence of surfactant, so dissolution studies were performed in solutions of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) at the CSC and above to prevent cocrystal conversions during dissolution. The effects of pH and surfactant concentration on the drug, CBZD and cocrystal dissolution were evaluated and compared in this study.

Materials and methods

Materials

Anhydrous carbamazepine (CBZ) and sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and used as received. Carbamazepine dihydrate (CBZD) was prepared by slurrying anhydrous CBZ in deionized water for 24 hours and solid was obtained through vacuum filtration and analyzed by XRPD. Water used in this study was filtered through a double deionized purification system. Cocrystals were prepared by reaction crystallization method at room temperature as described previously.16

Solubility experiments

Cocrystal and CBZD solubility were measured in previous publication by determining the eutectic concentrations of the drug and coformer as a function of SLS concentration at pH 1 and 25°C.16 A detailed discussion of the eutectic point measurement was reported elsewhere.17 Cocrystal stoichiometric solubility was determined from the measured eutectic concentrations of the components using the previously developed method.16,17

Dissolution experiments

Dissolution rates of cocrystals were determined in a previous publication using a rotating disk apparatus.16 In this work, CBZD powder (~150 mg) was compressed in a stainless steel rotating disk die with a tablet radius of 0.50 cm at 85 MPa for 2 minutes using a manual hydraulic press. The compressed disk was exposed to 150 mL of the dissolution medium in a water jacketed beaker with temperature controlled at 25°C and a rotation speed of 200 rpm was used. Dissolution medium was prepared on the day of the experiment by dissolving SLS in water. Sink conditions were maintained throughout the experiments (eg: less than 10% saturation). Solution concentrations were measured using HPLC and solid phases after dissolution were analyzed by XRPD.

HPLC

Waters HPLC with a photodiode array detector was used for all analysis. The mobile phase was composed of 55% methanol and 45% water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and the flow rate of 1 mL/min was used as described previously. Separation was achieved using Waters, Atlantis, T3 column (5.0 µm, 100 Å) with dimensions of 4.6 × 250 mm. The sample injection volume was 20 µL. The wavelengths used for CBZ was 284 nm.

XRPD

XRPD analysis of solid phases was done with a benchtop Rigaku Miniflex X-ray diffractometer using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å), a tube voltage of 30 kV, and a tube current of 15 mA. Data was collected from 5 to 40° at a continuous scan rate of 2.5°/min.

Theoretical

The solubility of non-ionizable drug in surfactant solution can be described as:

| (1) |

where S0 is the intrinsic solubility of the drug in aqueous phase, is the solubilization constant of the drug in surfactant solution and [m] is the micellar concentration.10

The solubility of a 1:1 cocrystal with non-ionizable drug and acidic coformer in surfactant solutions can be described as:

| (2) |

where Ksp is the cocrystal solubility product, is the coformer solubilization constant, and Ka is the coformer ionization constant.10 In this equation the solubilization of the ionized form of the coformer in surfactant solution is assumed to be negligible.

The cocrystal solubility advantage (SA) is defined as the solubility of cocrystal over that of the drug. Specifically, SA under the influence of pH and surfactant is defined as:

| (3) |

For rotating disk dissolution, the flux of both drug and cocrystal in surfactant solution can be described as follows:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where DReff and DCCeff are the effective diffusivities of the drug and cocrystal respectively, ω is the rotation speed during dissolution, ν is the viscosity of the dissolution media and is the pH at the dissolving surface.16,18,19 The effective diffusivity in surfactant solution is defined as:

| (6) |

where Daq is the aqueous diffusivity and Dm is the micellar diffusivity.16,18,19

The cocrystal dissolution advantage, ∅, is defined as the ratio of the cocrystal flux over the drug flux, which is given by:

| (7) |

A ∅ value greater than 1 indicates the cocrystal has higher dissolution rate than the drug; whereas the dissolution rate of cocrystal is less than the drug with a ∅ value below 1. Equation 7 is specific for determining the cocrystal dissolution advantage utilizing rotating disk dissolution methodology containing surfactant. However, a simplified equation can be derived to apply for dissolution under different conditions:

| (8) |

where is the diffusivity advantage and SA is the solubility advantage of cocrystal described above.

Utilizing the more classical diffusion layer model of Nernst-Brunner20, dissolution flux can also be described as:

| (9) |

where ℎ is the diffusion layer thickness. Applying the Nernst-Brunner diffusion model, the dissolution advantage of cocrystal is given by

| (10) |

Cocrystal dissolution advantage can therefore be predicted under different solution conditions from a knowledge of cocrystal diffusivity advantage and solubility advantage (SA). Cocrystal dissolution advantage would only depend on SA if the diffusion coefficient is the same for drug and cocrystal. This is usually true under aqueous conditions without surfactant. However, in the presence of surfactant, the effective diffusion coefficient of drug may be different from the cocrystals due to their different solubility dependence on surfactant concentration. Therefore, besides SA, the effective diffusion coefficients of both drug and cocrystal have to be taken into consideration as well, for determining the cocrystal dissolution advantage in the presence of surfactant. Due to the different diffusion coefficients, a dissolution advantage can be imparted to cocrystals with SA <1, as long as the diffusion advantage provided by the cocrystals is large enough to compensate for any disadvantage in solubility.

Results and discussion

Solubility

The equilibrium solubility of cocrystals as a function of surfactant concentration at pH 1 was determined from measurements at eutectic points.16,21 At the eutectic point, the solid phases of both drug and cocrystal are in equilibrium with solution and the concentrations of both cocrystal components can be measured.17 The relative solubility of the cocrystal to the parent drug can be assessed by the eutectic constant, Keu, which is a ratio of the coformer eutectic concentration over the drug eutectic concentration.17,22 Cocrystal (of 1:1 stoichiometry) is more soluble than the parent drug when Keu > 1; and less soluble than the parent drug when Keu < 1.17,22

The eutectic concentrations of cocrystal components and Keu as a function of the surfactant, sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) concentration at pH 1 are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The concentrations of both components increased with surfactant concentration; however, the drug concentrations are higher than the coformer concentrations at all surfactant concentrations. This is expected because all the solubility studies were performed at surfactant concentrations above the CSC, where the cocrystals are less soluble. The eutectic constants shown in Figures 1 and 2 further confirm the cocrystal thermodynamic stability under these conditions. Keu values decreased as SLS concentration increased because the surfactant concentration is higher than the CSC.

Figure 1.

a) Eutectic concentrations of CBZ (

) and SAC (

) and SAC (

) measured at the eutectic point for CBZ-SAC at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Keu values calculated from the eutectic concentrations.

) measured at the eutectic point for CBZ-SAC at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Keu values calculated from the eutectic concentrations.

Figure 2.

a) Eutectic concentrations of CBZ (

) and SLC (

) and SLC (

) measured at the eutectic point for CBZ-SLC at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Keu values calculated from the eutectic concentrations.

) measured at the eutectic point for CBZ-SLC at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Keu values calculated from the eutectic concentrations.

The equilibrium solubility of cocrystals were calculated from the eutectic concentrations of cocrystal components using the following equation:17

| (11) |

Not only the cocrystal solubility, but the drug solubility can also be determined from the eutectic measurement (Sdrug = [drug]eutectic) as the two are the equilibrium solid phases at the eutectic point. Although the drug solubility was determined in the presence of coformer, previous studies from our laboratory have shown that the solubilization of CBZD by SLS is not affected by coformer at the concentrations and pH studied.10,12,13 The solubility of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC were determined and are compared to CBZD in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Solubility of both drug and cocrystals increased as surfactant concentration increased, however, the drug has a greater rate of increase compared to cocrystals. This behavior is well recognized.10,12,13 As shown by equations 1 and 2, drug solubility has a linear dependence on the micellar concentration, while cocrystal has a square root dependence. This explains why the drug has a greater increase in solubility as a function of micellar concentration compared to the cocrystals. The square root dependence of cocrystal solubility on micellar concentration is a result of the preferential solubilization of the drug compared to the coformers by surfactant.10,12,13 Since the solubility studies were performed above the CSC, both cocrystals exhibit no solubility advantage over the parent drug, SA<1, as indicated in Figures 3 and 4. SA for both cocrystals decreased as SLS concentration increased due to increasing drug solubilization.6

Figure 3.

a) Solubility of CBZD (

) and CBZ-SAC (

) and CBZ-SAC (

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Solubility advantage of CBZ-SAC, Scc/Sdrug, calculated from the solubility data.

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Solubility advantage of CBZ-SAC, Scc/Sdrug, calculated from the solubility data.

Figure 4.

a) Solubility of CBZD (

) and CBZ-SLC (

) and CBZ-SLC (

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Solubility advantage of CBZ-SLC, Scc/Sdrug, calculated from the solubility data.

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration.21 b) Solubility advantage of CBZ-SLC, Scc/Sdrug, calculated from the solubility data.

Surfactant effects on drug and cocrystal dissolution

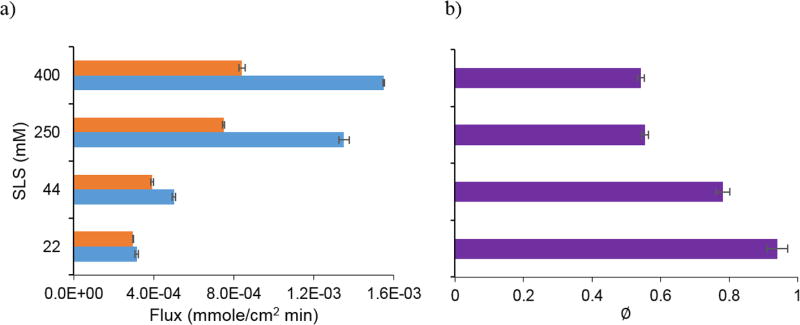

Dissolution studies of CBZD, CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC were performed at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration. The flux values of CBZD are compared to CBZ-SAC in Figure 5 and CBZ-SLC in Figure 6. Flux of both drug and cocrystals increased with SLS, however, a greater increase is observed for drug than for cocrystals. As the drug is preferentially solubilized by micelle, excess coformer is left in the aqueous pseudophase to stabilize the cocrystals. Because of this phenomenon, the solubility and thus flux dependence on surfactant is lower for the cocrystal than for the drug.

Figure 5.

a) Flux of CBZD (

) and CBZ-SAC21 (

) and CBZ-SAC21 (

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration. b) Dissolution advantage (∅) of CBZ-SAC calculated from the experimental flux.

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration. b) Dissolution advantage (∅) of CBZ-SAC calculated from the experimental flux.

Figure 6.

a) Flux of CBZD (

) and CBZ-SLC21 (

) and CBZ-SLC21 (

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration. b) Dissolution advantage (∅) of CBZ-SLC calculated from the experimental flux.

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS concentration. b) Dissolution advantage (∅) of CBZ-SLC calculated from the experimental flux.

Cocrystal dissolution advantage was determined by comparing the cocrystal flux to CBZD flux. Both cocrystals have no dissolution advantage over the parent drug under these dissolution conditions as indicated by ∅ < 1 shown in Figures 5 and 6. Under these conditions, the drug solubility is higher than both cocrystals. This means that the flux of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC is lower than CBZD. As shown in equation 8, ∅ is proportional to SA, so it follows the same dependence of SA on micellar concentration, in which the dissolution advantage decreases with increasing SLS concentration.

Micellar diffusion coefficients

Micellar diffusion coefficients of CBZ as a function of SLS concentration have been determined from the dissolution of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC in a previous study.16 Micellar diffusion coefficients determined for the two cocrystals were different from each other and this difference may be due to the different chemical environment surrounding the micelles during dissolution.16 Using equations 4, 5 and 6, micellar diffusion coefficients of CBZ were determined from the dissolution of CBZD as a function of SLS concentration at pH 1. These micellar diffusivities were compared to those determined from the dissolution of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Micellar diffusivities of CBZ determined from the dissolution of CBZD (

), CBZSAC21 (

), CBZSAC21 (

) and CBZ-SLC21 (

) and CBZ-SLC21 (

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS. The circles represent the experimental data and the solid lines represent the power regression analyses.

) at pH 1 as a function of SLS. The circles represent the experimental data and the solid lines represent the power regression analyses.

The micellar diffusivities of CBZ determined from the dissolution of CBZD follow the same trend as the ones of cocrystals. As shown in Figure 7, micellar diffusivities decrease with increasing surfactant concentration and this relationship can be fitted to a power equation. The decrease in micellar diffusivities is possibly due to the increase in micellar size or electric repulsion as SLS concentration increases, and a more detailed explanation was provided elsewhere.16 Among the three sets of micellar diffusion coefficients, the ones determined from the dissolution of CBZD are the lowest. Detailed analysis of this is beyond the scope of this study. However, the difference in solubility dependence on surfactant concentration between the drug and cocrystal could be the potential reason for the difference in micellar diffusion coefficients. The solubility of CBZD has a stronger dependence on surfactant concentration compared to the cocrystals as indicated by the linear dependence shown in equation 1. It is possible that more drug molecules are solubilized into the micelles during the dissolution of CBZD compared to the dissolution of the cocrystals and thus results in slower micellar diffusion compared to the cocrystals.

Solubility and dissolution enhancements by SLS

Due to micellar solubilization, the solubility and dissolution of CBZD and the two cocrystals can be enhanced in the presence of surfactant. As no measurements were conducted in the absence of surfactant, enhancements by SLS for CBZD, CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC were determined by normalizing the solubility and dissolution data at all surfactant concentrations to those at the lowest SLS concentration (22 mM). As shown in Figure 8, both solubility and dissolution enhancements increase as surfactant concentration increases, however, the solubility enhancement is greater than that for dissolution and this difference increases with surfactant.

Figure 8.

Solubility (

) and dissolution (

) and dissolution (

) enhancements of CBZD (a), CBZ-SAC (b) and CBZ-SLC (c) at pH 1 as a function of SLS. Both solubility and dissolution enhancements were determined by normalizing the data to 22 mM SLS.

) enhancements of CBZD (a), CBZ-SAC (b) and CBZ-SLC (c) at pH 1 as a function of SLS. Both solubility and dissolution enhancements were determined by normalizing the data to 22 mM SLS.

According to equations 4 and 5, the flux of the drug and cocrystal are proportional to solubility, so the dissolution enhancement should theoretically be proportional to the solubility enhancement. However, surfactant increases solubility of a compound by micellar interactions, but at the same time, it decreases the diffusivity of the solubilized compound. Similar behavior is well recognized for single component crystals.23–25 The counter effect of surfactant on solubility and micellar diffusivity results in lower dissolution enhancement compared to the solubility enhancement. This counter effect increases as surfactant concentration increases and results in greater difference between the solubility and dissolution enhancements. As expected, both solubility and dissolution enhancements of CBZD are higher than those of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC because of the higher solubility dependence on surfactant.

Cocrystal solubility and dissolution advantage comparison

The solubility and dissolution advantage of cocrystals as a function of SLS concentration were compared and shown in Figure 9. Both solubility and dissolution advantage decrease with increasing SLS concentration because the surfactant concentration increases above the CSC. However, the dissolution advantage of both cocrystals is higher than the solubility advantage at all surfactant concentrations. According to equation 7, dissolution advantage depends on both the solubility and diffusivity advantage. As discussed earlier, the micellar diffusivities of CBZ determined from the dissolution of CBZD are smaller than those determined from both of the cocrystals. Therefore, the dissolution advantage of both cocrystals is enhanced by the higher micellar diffusivity compared to the parent drug. The enhancement in dissolution advantage of CBZ-SLC is greater than CBZ-SAC because there are larger differences in the micellar diffusivities between CBZD and CBZ-SLC.

Figure 9.

Solubility (

) and dissolution (

) and dissolution (

) advantage of CBZ-SAC (a) and CBZ-SLC (b) at pH 1 as a function of SLS.

) advantage of CBZ-SAC (a) and CBZ-SLC (b) at pH 1 as a function of SLS.

pH effects on drug and cocrystal dissolution

Cocrystals with acidic coformers, SAC and SLC, enable the nonionizable drug, CBZD, to possess pH dependent dissolution. Figures 10 and 11 show the effect of bulk pH on cocrystal and drug dissolution at constant surfactant concentration16,21. The flux of CBZD was predicted to be constant as a function of bulk pH due to its nonionizable property. Since pH has no effect on the dissolution of CBZD, dissolution experiments were conducted in SLS solutions with no pH adjustment. The flux of both CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC increased with bulk pH because of the coformer acidity. However, the flux of both cocrystals plateau at bulk pH ranges from 4 to 8, where the coformers are self-buffering the pH microenvironment at the dissolving surface. Interfacial pH is relatively constant in this region, so no significant change in flux is observed in this region.

Figure 10.

a) Flux of CBZD and CBZ-SAC at 400 mM SLS as a function of bulk pH. b) Dissolution advantage, ∅, of CBZ-SAC calculated from the experimental flux. The flux of CBZD (

) is predicted using equation 4 and the flux of CBZ-SAC (

) is predicted using equation 4 and the flux of CBZ-SAC (

) is predicted using equation 5. CBZD experimental flux:

) is predicted using equation 5. CBZD experimental flux:

; CBZ-SAC experimental flux:

; CBZ-SAC experimental flux:

.

.

Figure 11.

a) Flux of CBZD and CBZ-SLC at 44 mM SLS as a function of bulk pH. b) Dissolution advantage, ∅, of CBZ-SLC calculated from the experimental flux. The flux of CBZD (

) is predicted using equation 4 and the flux of CBZ-SLC (

) is predicted using equation 4 and the flux of CBZ-SLC (

) is predicted using equation 5. CBZD experimental flux:

) is predicted using equation 5. CBZD experimental flux:

; CBZ-SAC experimental flux:

; CBZ-SAC experimental flux:

.

.

Cocrystal dissolution advantage, ∅, was determined from the experimental cocrystal to CBZD flux ratio and these values are shown in Figure 10 for CBZ-SAC and Figure 11 for CBZ-SLC. These results show that there is a transition pH where the flux of the drug is equal to the cocrystal flux. Below this transition pH, the drug flux is higher than cocrystal, and above it, the cocrystal flux becomes higher than drug.

These cocrystals were not expected to have a dissolution advantage under these conditions since dissolution studies were performed above the CSC where solid cocrystals are thermodynamically stable. Both cocrystals have no solubility advantage over the parent drug as indicated by the ratios of SA less than 1 shown in Tables 1 and 2. Despite the lower solubility, CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC can still display higher dissolution rates compared to CBZD above the transition pH. According to equation 7, ∅ is dependent on not only SA, but also on the diffusivity advantage. As shown in Figure 7, the effective diffusivities of CBZ determined from the dissolution of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC are higher than those of CBZD. The effective diffusion coefficients of CBZ-SAC at 400 mM SLS and CBZ-SLC at 150 mM SLS are about 1.7× and 2.1× higher than those of CBZD, respectively. Such differences in effective diffusion coefficients are not large enough to impart a dissolution advantage for both cocrystals below the transition pH because SA is too low under these conditions as shown in Tables 1 and 2. As the SA becomes higher above the transition pH, the higher effective diffusivities of both cocrystals are able to compensate for the disadvantage in solubility and impart a dissolution advantage.

Table 1.

Theoretical predictions of dissolution advantage for CBZ-SAC at 400 mM SLS as a function of pH.

| pH | Solubilityb (mM) | Scc/Sdrug | Deff,R (cm2/sec) | Predicted ∅d |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk | Interfaciala | CBZD | CBZ- SAC |

CBZD | CBZ-SACc | ||

| 1.27 | 1.27 | 74.2 | 30.4 | 0.41 | (4.16±0.02)E-7 | (7.2±0.3)E-7 | 0.59 |

| 2.16 | 2.15 | 36.8 | 0.50 | 0.72 | |||

| 3.02 | 2.78 | 54.6 | 0.74 | 1.07 | |||

| 4.03 | 3.00 | 66.2 | 0.89 | 1.28 | |||

| 5.97 | 3.03 | 68.0 | 0.92 | 1.33 | |||

| 7.66 | 3.03 | 68.0 | 0.92 | 1.33 | |||

From reference16.

Predicted from equation 1 for CBZD and equation 2 for CBZ-SAC.

From reference16.

Predicted from equation 7.

Table 2.

Theoretical predictions of dissolution advantage for CBZ-SLC at 44 mM SLS as a function of pH.

| pH | Solubilityb (mM) | Scc/Sdrug | Deff,R (cm2/sec) | Predicted ∅d |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk | Interfaciala | CBZD | CBZ- SLC |

CBZD | CBZ-SLCc | ||

| 1.15 | 1.15 | 12.2 | 6.53 | 0.54 | (1.41±0.04)E-6 | (2.98±0.04)E-6 | 0.88 |

| 3.08 | 2.97 | 6.27 | 0.51 | 0.84 | |||

| 5.05 | 3.65 | 8.49 | 0.70 | 1.15 | |||

| 5.99 | 3.66 | 8.55 | 0.70 | 1.15 | |||

| 7.49 | 3.66 | 8.55 | 0.70 | 1.15 | |||

From reference16.

Predicted from equation 1 for CBZD and equation 2 for CBZ-SAC.

From reference16.

Predicted from equation 7.

From knowledge of the SA and diffusivity advantage, the cocrystal dissolution advantage can be predicted using equation 7. The predicted dissolution advantage of CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC is shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. These predicted values agree well with the experimental values shown in Figures 10 and 11. The higher effective diffusivities of cocrystals are able to compensate for the disadvantage in solubility and result in a dissolution advantage for both cocrystals without having to deal with cocrystal conversions during dissolution.

Dissolution conditions for maintaining cocrystal dissolution advantage

Solid phase transformation is one of the challenges for the development of cocrystals because it can lead to minimal or no dissolution advantage compared to the parent drug. The enhanced dissolution rate through cocrystallization can potentially increase the bioavailability of the parent drug. Therefore, it would be beneficial to formulate a cocrystal that can exhibit higher dissolution rate than the parent drug without having to deal with solid phase transformation during dissolution. It is possible to develop such formulations because the effective diffusivity of the cocrystal in the presence of surfactant is found to be larger than the drug and this allows the cocrystal to achieve dissolution advantage even if it has lower solubility than the parent drug. Knowledge of the dissolution behavior of cocrystals would help to develop feasible formulations.

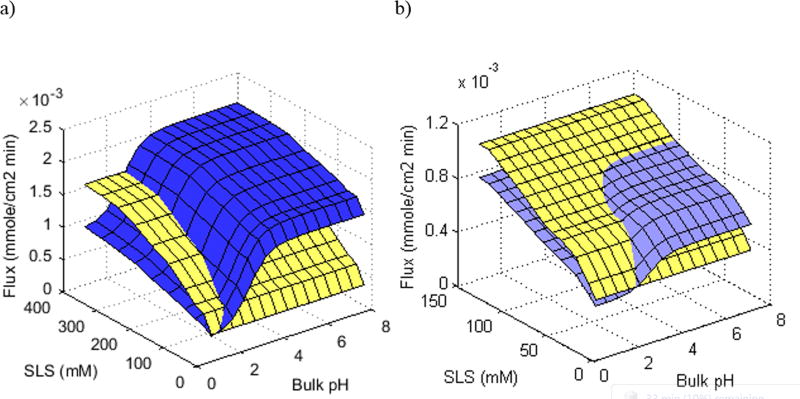

To evaluate the dissolution conditions in which the cocrystals can maintain both dissolution advantage and thermodynamic stability for formulation development, the combination effect of pH and surfactant concentration on the dissolution of CBZD is compared to CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC in Figure 12. Because of the nonionizable property, the dissolution rate of CBZD is only affected by the surfactant concentration, whereas the cocrystals are affected by both surfactant and pH because of the acidity of the coformers.

Figure 12.

(a) Theoretical flux comparison of CBZD (yellow) to CBZ-SAC (blue), and (b) CBZD (yellow) to CBZ-SLC (purple) as a function of pH and SLS concentration. Flux predictions of CBZD were determined using equation 4 and cocrystals were from reference21.

As shown in Figure 12, CBZ-SAC is able to achieve a dissolution advantage from bulk pH 3 to 8 at SLS concentrations ranging from 22 to 400 mM. However, CBZ-SAC is not thermodynamically stable under all these conditions. The CSC for CBZ-SAC at bulk pH 3 is 161 mM SLS and from bulk pH 4 to 8 it is 306 mM. This suggests that CBZ-SAC would be able to maintain a dissolution advantage without phase transformation at bulk pH 3 with SLS concentration of 161 mM and above; and from bulk pH 4 to 8 with SLS concentration of 306 mM and above. These surfactant concentrations may be too high to be considered for oral administration. However, the CSC for CBZ-SLC at bulk pH up to 8 is only 21 mM SLS. This means that CBZ-SLC is thermodynamically stable and less soluble than CBZD under all the dissolution conditions shown in Figure 12. Although it is less soluble than CBZD, CBZ-SLC is able to maintain a dissolution advantage at SLS concentrations ranging from 22 to 90 mM and bulk pH ranging from 4 to 8 because of the higher effective diffusivities. These SLS concentrations may still be considered high for oral administration as the highest amount of SLS found in approved drug products is 96 mg.26 However, a surfactant with stronger solubilization toward the drug may able to achieve the same benefit with a lesser amount.

Conclusions

This work compares the solubility, diffusivity, and dissolution of CBZD and its two cocrystals, CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC as a function of pH and surfactant concentration. Solubility, diffusivity, and dissolution pH dependence are imparted to CBZ by cocrystallization with acidic coformers. Because of the preferential solubilization of the drug over the coformers, the solubility and diffusivity dependence of the drug is different from the cocrystals. Cocrystal dissolution advantage can be determined by comparing the cocrystal flux to the drug flux. Based on the mass transport analyses, cocrystal dissolution advantage is proportional to both the solubility and diffusivity advantage. In this study, the micellar diffusivities of CBZ determined from the dissolution of CBZD are found to be less than the cocrystals. Because of the greater cocrystal diffusivities, cocrystals with lower solubility than the parent drug do not necessarily have slower dissolution rates. The diffusivity advantage of the cocrystals studied here results in the cocrystals demonstrating higher dissolution rates than the drug even though they possess lower solubility. Dissolution conditions where the cocrystal can exhibit both thermodynamic stability and a dissolution advantage is useful information for cocrystal formulation development and these conditions can be evaluated through the simple mass transport models provided in this work.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM107146. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also gratefully acknowledge partial financial support from the College of Pharmacy, University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alhalaweh A, Roy L, Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Velaga SP. pH-Dependent Solubility of Indomethacin-Saccharin and Carbamazepine-Saccharin Cocrystals in Aqueous Media. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2012;9:2605–2612. doi: 10.1021/mp300189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bethune SJ, Huang N, Jayasankar A, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Understanding and Predicting the Effect of Cocrystal Components and pH on Cocrystal Solubility. Crystal Growth and Design. 2009;9(9):3976–3988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamara DP, Childs SL, Giordano J, Iarriccio A, Cassidy J, Shet MS, Mannion R, O'Donnell E, Park A. Use of a glutaric acid cocrystal to improve oral bioavailability of a low solubility API. Pharmaceutical Research. 2006;23(8):1888–1897. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Childs SL, Kandi P, Lingireddy SR. Formulation of a Danazol Cocrystal with Controlled Supersaturation Plays an Essential Role in Improving Bioavailability. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2013;10(8):3112–3127. doi: 10.1021/mp400176y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheney ML, Weyna DR, Shan N, Hanna M, Wojtas L, Zaworotko MJ. Supramolecular Architectures of Meloxicam Carboxylic Acid Cocrystals, a Crystal Engineering Case Study. Crystal Growth & Design. 2010;10:4401–4413. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuminek G, Cao F, Rocha ABdOd, Cardoso SG, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Cocrystals to Facilitate Delivery of Poorly Soluble Compounds Beyond-Rule-of-5. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.022. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Nehm SJ, Jayasankar A. Encyclopedia of PHarmaceutical Technology. London, United Kingdom: Francis and Taylor; 2007. Cocrystals: Design, Properties, and Formation Mechanisms; pp. 615–635. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vishweshwar P, McMahon JA, Bis JA, Zaworotko MJ. Pharmaceutical Co-Crystals. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006;95(3):499–516. doi: 10.1002/jps.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amidon GL, Lennernas H, Shah VP, Crison JR. A Theoretical Basis for a Biopharmaceutic Drug Classification: The Correlation of in Vitro Drug Product Dissolution and in Vivo Bioavailability. Pharmaceutical Research. 1995;12(3):413–420. doi: 10.1023/a:1016212804288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang N, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Engineering Cocrystal Solubility, Stability, and pHmax by Micellar Solubilization. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;100(12):5219–5234. doi: 10.1002/jps.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuminek G, Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Siedler S, Rocha HVA, Cuffini SL, Cardoso SG. How Cocrystals of Weakly Basic Drugs and Acidic Coformers Might Modulate Solubilty and Stability. CHem Commun. 2016;52(34):5832–5835. doi: 10.1039/c6cc00898d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang N, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Engineering Cocrystal Thermodynamic Stability and Eutectic Points by Micellar Solubilization and Ionization. Cryst Eng Comm. 2011;13:5409–5422. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang N, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Effect of Micellar Solubilization on Cocrystal Solubility and Stability. Crystal Growth & Design. 2010;10:2050–2053. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipert MP, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Cocrystal Transition Points: Role of Cocrystal Solubility, Drug Solubility, and Solubilizing Agents. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2015;12(10):3535–3546. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maheshwari C, Andre V, Reddy S, Roy L, Duarte T, Rodrigez-Hornedo N. Tailoring aqueous solubility of a highly soluble compound via cocrystallization: effect of coformer ionization, pH(max) and solute-solvent interactions. Crystengcomm. 2012;14(14):4801–4811. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao F, Amidon GL, Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Amidon GE. Mechanistic Analysis of Cocrystal Dissolution as a Function of pH and Micellar Solubilization. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2016;13(3):1030–1046. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Good DJaR-H, N. Solubility Advantage of pHarmaceutical Cocrystals. Crystal Growth & Design. 2009;9(5):2252–2264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amidon GE, Higuchi WI, Ho NFH. Theoretical and experimental studies of transport of micelle solubilized solutes. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1982 Jan;71:77–84. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600710120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crison JR, Shah VP, Skelly JP, Amidon GL. Drug Dissoluiton into Micellar Solutions: Development of a Convective Diffusion Model and Comparison to the Film Equilibrium Model with Application to Surfactant-Facilitated Dissolution of Carbamazepine. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1996;85(9):1005–1011. doi: 10.1021/js930336p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunner E. Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit in Heterogenen Systemen. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 1904;47:56–102. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao F, Amidon G, Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Amidon G. Mechanistic Analysis of Cocrystal Dissolution as a Function of pH and Micellar Solubilization. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2015;13(3):1030–1046. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Good DJ, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Cocrystal Eutectic Constants and Prediction of Solubility Behavior. Crystal Growth & Design. 2010;10(3):1028–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao VM, Lin M, Larive CK, Southard MZ. A Mechanistic Study of Griseofulvin Dissolution into Surfactant Solutions Under Laminar Flow Conditions. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1997;86(10):1132–1137. doi: 10.1021/js9604974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun W, Larive CK, Southard MZ. A Mechanistic Study of Danazol Dissolution in Ionic Surfactant Solutions. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2003;92(2):424–435. doi: 10.1002/jps.10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen A, Wu D, Johnson CS. Determination of the Binding Isotherm and Size of the Bovine Serum Albumin-Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Complex by Diffusion-Ordered 2D NMR. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1995;99(2):828–834. [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA Inactive Ingredient List. 2017 [Google Scholar]