Abstract

Background

Lay support has been associated with improved breastfeeding practices, but studies of programs that engage men in breastfeeding support have shown mixed results and most are from high-income countries. The purpose of our research is to review strategies to engage men in exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) promotion or support in 28 project areas across 20 low- and middle-income countries. This information may be used to inform program implementers and policymakers seeking to increase EBF.

Methods

We tested the difference between baseline and final EBF proportions using Pearson’s chi-square (a = 0.05) and identified project areas with a significant increase. We categorized male engagement strategies as low- and high-intensity, using information from project reports. We looked for patterns by intensity and geography and described strategies used to engage men in different places.

Results

Twenty-eight projects were reviewed; 21 (75%) were in areas where a statistically significant increase in EBF was observed between the beginning and end of the project. A variety of high- and low-intensity male engagement strategies was used in areas with an increase in EBF prevalence and in all geographic regions. High-intensity strategies engaged men directly during home or health visits by forming men’s groups and by working with male community leaders or members to promote EBF. Low-intensity strategies included large community meetings that included men, and radio messages, and other behavior change materials directed towards men.

Conclusion

Male engagement strategies took many forms in these project areas. We did not find consistent associations between the intensities or types of male engagement strategies and increases in EBF proportions. There is a gap in understanding how gender norms might impact male involvement in women’s health behaviors. This review does not support the broad application of male engagement to improve EBF practices, and we recommend considering local gender norms when designing programs to support women to EBF.

Keywords: Exclusive breastfeeding, Male involvement, Gender

Background

Gender factors affect maternal and child health in many ways and often manifest in terms of gender inequality through control of resources, decision-making, and access to health information, which can affect behaviors that in turn affect the mother’s and her child’s health [1]. The relationship of breastfeeding with gender equality raises the question of whether breastfeeding is solely the responsibility of the mother [2]. Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) has been shown to provide immediate and long-term benefits for both mothers and children [3–7]. Both skilled and lay (e.g., peer) support have been shown to reduce the risk of suboptimal breastfeeding practices [8, 9] with face-to-face support being the most effective for EBF [8], but effective approaches and strategies to support in different geographic, cultural, and income contexts are still being studied.

A key constraint to EBF in some lower- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is lack of knowledge and support from household members who wield authority over many household practices, including infant feeding decisions, particularly fathers and grandmothers [10–13]. There have been many social and behavior change efforts to engage men in reproductive health program interventions, but evidence regarding the impact on breastfeeding practice is mixed [1, 14]. Moreover, many of the studies about engaging men in EBF promotion and support were in higher-income countries and are thus of unknown relevance to LMIC (e.g., [15–20]).

The few studies conducted in LMIC showed positive EBF outcomes when men were included in interventions. An intervention in Vietnam providing fathers with breastfeeding education materials, counseling, and household visits found significantly higher EBF at 4 and 6 months, compared to mothers whose partners were not in the intervention group [21]. Similarly, an intervention in Turkey found that EBF prevalence was highest in a group where both mothers and fathers received breastfeeding education, compared to a group where only mothers received it [22]. A clinical trial in Brazil found that EBF increased where fathers were included in a breastfeeding education program [23].

Since 1985, the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Child Survival and Health Grants Program (CSHGP) has supported nongovernmental organizations’ (NGO) efforts to reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality through interventions designed to address health issues, including EBF. USAID provides technical assistance to NGOs in designing, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating these projects, and maintains a database for project information.

The purpose of our research was to review strategies to engage men in supporting the practice EBF by their partner in 28 CSHGP project areas in 20 LMIC. This information may inform program implementers and policymakers seeking to increase EBF practices. Documenting and disseminating results from community-based programs in a variety of country contexts can inform strategies to reach global goals to reduce preventable child deaths.

Methods

We included all CSHGP projects beginning and ending between 2003 and 2013 that (1) reported engaging men in EBF support, (2) were conducted in LMIC in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, South and Central Asia, or Latin America/Caribbean regions, and (3) had complete survey data. We considered survey data complete if the questions included the number of infants under 6 months of age who were exclusively breastfed in the previous 24 h, and the total number of infants under 6 months of age in the survey, with no indication of data quality concerns in the final evaluation report. The University of North Carolina’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study was not human subject research and does not require IRB approval. It is an analysis of secondary data (project reports) with no personal identifiers.

Quantitative methods

Each NGO conducted population-based knowledge, practice, and coverage surveys in their project areas at the beginning and end of their projects. These surveys were designed and conducted with assistance from USAID and employed a standardized methodology, including obtaining informed consent and data collection instruments designed by survey sampling and design experts [24]. NGOs used either 30-cluster or Lot Quality Assurance sampling methodologies to obtain project area prevalence estimates for EBF. With permission from the USAID, we extracted data from the CSHGP database and project reports. The standard calculation of EBF prevalence is the number of infants under 6 months of age who were given only breast milk in the 24 h preceding the survey divided by the number of infants under 6 months of age surveyed, times 100. We calculated Pearson chi-square statistics to test the association between time (baseline or final) and EBF using SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC). That test indicates if the proportions are statistically different at a = 0.05.

Qualitative methods

We extracted qualitative information about EBF promotion and support strategies from project reports and thematically analyzed it to aid interpretation of our results. Our primary search terms included men, husband(s), father(s), exclusive, breastfeeding, and LAM (lactational amenorrhea method—a modern contraceptive method that requires full breastfeeding as one of the criteria for use). If searching for men, husband(s), and father(s) yielded no results, we searched for family, partner, male, and decision-maker. Upon identification of keywords in the text, we reviewed the report and any relevant annexes to ascertain the strategies used to engage men. We populated a matrix with information extracted from the reports related to male roles, EBF promotion or support activities that engaged men, activity frequency and timing, intensity of male engagement strategy, as well as quotes about male engagement or lack of male engagement, other EBF promotion or support activities, and other project health activities that did not engage men. We then organized male engagement activities by intensity and geographic region. We categorized male engagement strategy into three levels by intensity: none, low, and high. “Low” included indirect male engagement strategies such as general mass outreach efforts such as community health fairs and mass media campaigns; “high” included male engagement strategies with direct personal contact, such as interpersonal communication through home visits or through groups such as community-based organizations.

Results

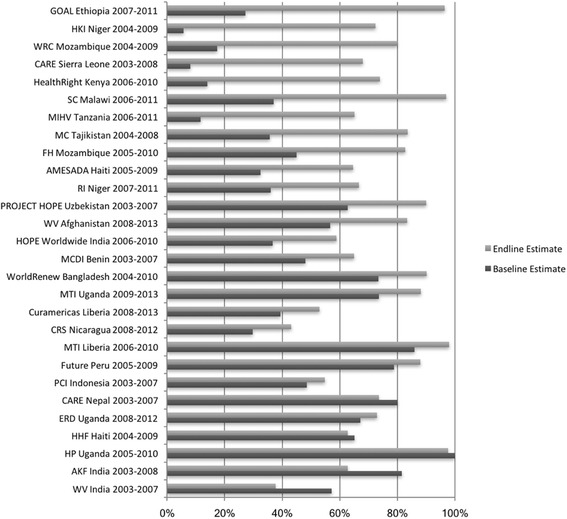

Twenty-eight projects that reported strategies to engage men to promote or support EBF were included (Fig. 1). Fifteen projects were implemented in sub-Saharan Africa, eight in South or Central Asia, four in the Latin America/Caribbean region, and one in Southeast Asia. Twenty-one project areas (75%) had significant increases in EBF prevalence at the end of project implementation (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for project selection

Table 1.

Project characteristicsa

| NGOb | Location | Years | Population | Baseline EBF prevalence (95% CI) | Final EBF prevalence (95% CI) | Region | Intensity of male engagement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | AKF | India | 2003–2008 | 88,128 | 80.1 (75.4–84.8) | 62.9 (51.2–74.6)* | SCA | High |

| 2. | AME-Sada | Haiti | 2005–2009 | 300,000 | 32.4 (15.6–49.2) | 64.8 (46.9–82.7)* | LAC | Low |

| 3. | CARE | Nepal | 2003–2007 | 931,054 | 66.8 (54.6–79.0) | 73.5 (66.6–80.4) | SCA | Low |

| 4. | CARE | Sierra Leone | 2003–2008 | 112,921 | 8.3 (1.6–15.0) | 68.4 (57.5–79.3)* | SSA | Low |

| 5. | CRS | Nicaragua | 2008–2012 | 113,560 | 29.7 (23.0–36.4) | 43.2 (35.1–51.3)* | LAC | High |

| 6. | Curamericas | Liberia | 2008–2013 | 149,322 | 39.4 (26.1–52.7) | 52.9 (39.2–66.6)* | SSA | Low |

| 7. | ERD | Uganda | 2008–2012 | 53,083 | 67.1 (60.8–73.4) | 73.0 (67.0–79.0) | SSA | High |

| 8. | FH | Mozambique | 2005–2010 | 254,282 | 40.0 (31.0–49.0) | 81.5 (73.8–89.2)* | SSA | High |

| 9. | FG | Peru | 2005–2009 | 119,478 | 79.0 (65.7–92.3) | 87.9 (73.1–100.0)c* | LAC | High |

| 10. | GOAL | Ethiopia | 2007–2011 | 168,636 | 27.2 (19.0–35.4) | 96.5 (93.1–99.9)* | SSA | High |

| 11. | HealthRight | Kenya | 2006–2010 | 257,083 | 13.8 (8.3–19.3) | 73.7 (64.8–82.6)* | SSA | High |

| 12. | HHF | Haiti | 2004–2009 | 171,703 | 65.1 (54.8–75.4) | 62.8 (52.6–73.0) | LAC | High |

| 13. | HP | Uganda | 2005–2010 | 759,201 | 100.0 (0) | 97.6 (92.9–100.0)c | SSA | Low |

| 14. | HKI | Niger | 2004–2009 | 359,400 | 5.7 (0–12.6)c | 72.4 (57.1–87.7)* | SSA | High |

| 15. | HW | India | 2006–2010 | 211,070 | 36.7 (21.4–52.0) | 58.9 (48.6–69.2)* | SCA | High |

| 16. | MC | Tajikistan | 2004–2008 | 204,448 | 35.6 (26.3–44.9) | 83.5 (72.7–94.3)* | SCA | High |

| 17. | MCDI | Benin | 2003–2007 | 146,210 | 48.0 (32.0–64.0) | 64.9 (54.2–75.6)* | SSA | High |

| 18. | MTI | Liberia | 2006–2010 | 127,124 | 86.0 (68.4–100.0)c | 98.0 (78.5–100.0)c* | SSA | High |

| 19. | MTI | Uganda | 2009–2013 | 113,400 | 73.6 (47.6–99.6) | 88.2 (78.9–97.5)* | SSA | High |

| 20. | PCI | Indonesia | 2003–2007 | 76,549 | 48.5 (36.4–60.6) | 54.8 (39.7–69.9) | SEA | High |

| 21. | Project HOPE | Uzbekistan | 2006–2011 | 315,962 | 62.7 (49.9–75.5) | 90.0 (84.5–95.5)* | SCA | High |

| 22. | RI | Niger | 2007–2011 | 454,869 | 36.1 (19.9–52.3) | 66.7 (53.9–79.5)* | SSA | Low |

| 23. | SC | Malawi | 2006–2011 | 724,873 | 36.6 (24.0–49.2) | 96.7 (90.4–100.0)c* | SSA | High |

| 24. | WI | Tanzania | 2006–2011 | 218,654 | 11.6 (2.0–21.2) | 65.1 (52.3–77.9)* | SSA | Low |

| 25. | WRC | Mozambique | 2004–2009 | 227,260 | 17.4 (6.8–28.0) | 80.0 (68.0–92.0)* | SSA | High |

| 26. | WR | Bangladesh | 2004–2010 | 169,803 | 74.2 (66.4–82.0) | 90.1 (85.9–94.3)* | SCA | High |

| 27. | WV | Afghanistan | 2008–2013 | 260,500 | 56.7 (42.6–70.8) | 83.5 (74.6–92.4)* | SCA | High |

| 28. | WV | India | 2003–2007 | 3,254,203 | 57.2 (48.9–60.5) | 37.7 (34.5–40.9)* | SCA | Low |

Abbreviations: NGO nongovernmental organization, CI confidence interval, SSA sub-Saharan Africa, AKF Aga Khan Foundation, SCA South and Central Asia, AME-Sada African Methodist Episcopal Church Service and Development Agency, LAC Latin America and Caribbean, ARC American Red Cross, SEA Southeast Asia, CHS Center for Human Services, CW Concern Worldwide, CI Counterpart International, CRS Catholic Relief Services, DRC Democratic Republic of Congo, ERD Episcopal Relief and Development, FH Food for the Hungry, FG Future Generations, HAI Health Alliance International, HHF Haitian Health Foundation, HP Health Partners, HKI Helen Keller International, HW Hope Worldwide, IRD International Relief and Development, MC Mercy Corps, MCDI Medical Care Development Inc., MTI Medical Teams International, PCI Project Concern International, Plan Plan International, RI Relief International, SAWSO Salvation Army World Service Organization, SC Save the Children, WI Wellshare International, WR World Relief, WR World Renew, WV World Vision

*Statistically significant (a = 0.05) difference in proportions (n = 23)

aAs reported by grantees to USAID

bAll projects are implemented in partnership with local health service providers, organizations or institutes

cThe confidence interval was truncated at the extreme value because the margin of error rendered an improbable confidence limit

Fig. 2.

Exclusive breastfeeding prevalence estimates at beginning and end of projects

High-intensity male engagement strategies were reported by 20 projects (Table 2). Sixteen (80%) of the 20 projects with high-intensity male engagement strategies were in areas where EBF prevalence significantly increased. The strategies included working within men’s groups (HealthRight, Kenya) and farmer development associations (Aga Khan Foundation, India and World Renew, Bangladesh); trained community members to promote EBF (Food for the Hungry, Mozambique); included men in-home visits (GOAL, Ethiopia and Mercy Corps, Tajikistan); implemented educational modules in the primary health centers specifically for couples (Project Hope, Uzbekistan), or created breastfeeding support groups for men (Helen Keller International, Niger). Some of these strategies were included in the project objectives from the planning stages, for example, as part of the project equity strategy (Helen Keller, Niger), while others were implemented after midterm evaluation findings indicated the need to engage men, considering women’s lack of decision-making authority in households (HealthRight, Kenya). There were no discernable geographic patterns in terms of the form of male engagement. Four projects with high-intensity strategies did not record an increase in EBF prevalence, and most of them (ERD, Uganda; AKF, India; and HHF, Haiti) provided health education to groups, such as farmers’ groups and fathers’ groups.

Table 2.

Descriptions of strategies utilized promote and support EBF, grouped by intensity of male engagement strategy and region

| NGO, country | Male engagement strategy | Other strategies |

|---|---|---|

| High intensity strategies to engage men in EBF promotion or support | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||

| ERD, Uganda | Community-based organizations (CBOs) such as literacy groups and farmers groups formed and discussed maternal and child health and nutrition topicsa; household visits to promote behavior change communication messages, including EBFb | Village health teams provided breastfeeding advice and information |

| FH, Mozambique* | Care Group model, with the majority of community-selected promotersb male (85%) | |

| GOAL, Ethiopia* | Community-level promotion of Community Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (CIMCI) and Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health and Nutrition (MNCH/N); conducted home visits using Care Group Modela | |

| HealthRight, Kenya* | Monthly meetings held with male dominated CBOs and Faith-based Organizations (FBOs) for health topic discussions and dissemination of behavior change communication (BCC) materials with community health workers (CHWs)a; home visits conducted by CHW for maternal and newborn health education entire familyb | Participated in week-long national promotion campaigns |

| HKI, Nigerc* | Breastfeeding Support Groups that included men and womenb; created community-based growth promotion teams including at least 1 man to disseminate Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA) messages (including EBF) at community eventsb | ENA committees also promoted EBF |

| MCDI, Beninc* | Targeted EBF behavior change information, education communication (IEC) materials, and radio spot messages towards fathers as household decision-makersb; men participated in community song festivals and radio contests with key breastfeeding messagesb | BCC and IEC materials for mothers, including radio spots, integrating matrons and mothers-in-law in breastfeeding promotion, VISA (leader) mothers and CHWs promoted messages and were trusted by the community |

| MTI, Liberiac* | Household Health Promoters provided home visits and community education sessionsb | Coordinated support for infant and young child feeding at community and facility levels. |

| MTI, Uganda* | Community-identified men trained as members of Village Health Teams to deliver health messages through community mobilization activities and IEC materials for project intervention areasb; men trained as peer educators to deliver weekly early child development modules to parentsb | |

| SC, Malawic* | Village Health Committees mobilized “core groups” of women and men to identify barriers to recommended practices and implement local activities related to newborn healthb; trained grandparents, including grandfathers, to give counseling and deliver health education messages on key maternal and newborn health topics, including essential newborn careb | Home visits to pregnant and postpartum women |

| WR, Mozambique* | Formed Care Groups with Pastors/Traditional Healers to share health messages with the communitya | |

| South and Central Asia | ||

| AKF, Indiac* | Health education in CBO meetings (e.g., Farmers Groups)a | |

| HW, India* | Trained Community Health Teams provided individual family or small group counseling from for fathers, mothers, pregnant women, etc.b; engaged religious leaders to communicate healthy behavior messages | |

| MC, Tajikistan* | Trained Community Health Educators and Village Development Committees (composed of local men and women) worked at community level by focusing behavior change and nutrition messaging towards household decision-makers (men and mothers-in-law)b | Mothers’ Groups/Breastfeeding Support Groups; support for district maternity houses to gain or renew Baby-Friendly status |

| Project HOPE, Uzbekistanc* | Trained community leaders to deliver health messages (including EBF) to families during household visits and community eventsb; created New Parents’ Schools in community health centers to educate expectant parents on health topics such as breastfeedingb | Assisted hospitals to gain Baby-Friendly certification; breastfeeding support groups at maternity houses; participation in annual Breastfeeding Week activities; monitoring Baby-Friendly policy adherence at maternity houses; dissemination of breastfeeding educational materials |

| WR, Bangladesh* | Used community based organization to form primary groups of men, including husbands and community leaders, to promote key family practices critical for child health and nutritiona | |

| WV, Afghanistan* | Formed community-level committees (shuras) to mobilize communities and health shura members to communicate messages from Home-based Life Saving Skills (HBLSS)b; conducted timed and targeted counseling home visits for pregnant women, other caregivers, and household decision-makersb; held community meetings for promoting HBLSS messagesb | Promoted and supported Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative; women peer groups |

| Southeast Asia | ||

| PCI, Indonesia | Community outreach and counseling events for parents and caregiversb | |

| Latin American and the Caribbean | ||

| CRS, Nicaraguac* | Behavior Change Agents using religious gatherings and sporting events to promote BCC strategies; specific program Engaging Men to Improve Care-Seeking; TBA home visits with women and partner to promote health topics, including EBFb | Strengthening health workers’ and volunteers’ capacities related to maternal and newborn nutrition |

| FG, Peru* | Community Health Agent home visits geared towards familiesb; general community assemblies discussing health issues of women and childrenb | Integrated with other health messages, e.g., EBF to prevent pneumonia; trained health facility staff and community health agents |

| HHF, Haiti | Organization of Fathers’ Groups for health education activitiesa; community meetings and demonstrationsb | |

| Low-intensity strategies to engage men in EBF promotion or support | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||

| Care, Sierra Leonec* | Formed community health clubs, with concerted effort to include men, and promoted health messages at meetingsb | Trained community-based growth promoters to promote EBF; pregnant women’s support groups and multisectoral activities promoted nutrition behaviors |

| Curamericas, Liberiac* | Behavior change communication activities in communities with messages targeted at both gendersb | |

| HP, Ugandac | Conducted community BCC sessions promoting breastfeedingb | Counseled mothers on breastfeeding; behavior change communication activities with men |

| RI, Niger* | Conducted meetings with husbands and village committees to promote behavior change communication messages, which include breastfeedinga | Promoted health behaviors with women’s health groups |

| WI, Tanzania* | Embedded EBF messages into other BCC message health topic areas, including diarrhea and pneumonia, at community eventsb | |

| South and Central Asia | ||

| Care, Nepalc | Behavior change communication strategy targeted husbands, including radio, TV and other IEC materials disseminated at community eventsb | Trained Female Community Health Volunteers to educate and counsel mothers |

| WV, Indiac* | Held community meetings to improve men’s engagement in family planning (especially LAM) and maternal and child nutrition | Timed counseling sessions with mothers; CHW training |

| Latin American and the Caribbean | ||

| AME-Sada, Haiti* | Organized community-wide rally posts to educate community, including fathers, in-laws, and grandmothers, to communicate specific behavior change messages, including EBFb | Trained CHWs, who made home visits; partnered with COZAM (breastfeeding promotion group); behavior change messages communicated through several media, including breastfeeding clubs and support groups |

*Statistically significant (a = 0.05) difference in proportions (n = 23)

aEngaged women in similar but separate activities as men for EBF promotion and support

bEngaged women alongside men in same activities for EBF promotion and support

cConducted formative research to inform strategies to engage men in EBF promotion and support; includes qualitative methods such as focus group discussion, barrier analysis, doer/nondoer analysis, or other surveys

Low-intensity male engagement strategies were used by the eight projects across nearly all regions and included large community meetings (Relief International, Niger; AME-Sada, Haiti, and World Vision, India), radio messages (Care, Sierra Leone), or other behavior change messaging and materials (Care, Nepal; Curamericas, Liberia; Wellshare International, Tanzania; and HealthPartners, Uganda). Six (75%) of the projects reporting low-intensity strategies to engage men worked where EBF prevalence significantly increased. One such project used a combination of low-intensity strategies with high frequency, including monthly community meetings and other behavior change communication materials (Care, Sierra Leone).

Eleven project reports also documented other strategies used to promote and support breastfeeding. These other strategies included training other influencers, such as mothers-in-law, strengthening community health workers’ capacities, and promoting behavior change in communities with various messages and media.

Discussion

This study reviewed projects that employed strategies to engage men in EBF promotion and support in several geographic settings and calculated EBF prevalence changes in project areas. No clear pattern emerged, in terms of increased EBF prevalence where certain strategies were employed or in the choice of strategies in different geographic areas. In addition, not every project area had an increase in EBF prevalence.

We do not know how effective the reported male engagement strategies were in engaging men because this type of analysis was not conducted as part of the project evaluations. Several independent project evaluators commented on male engagement, or lack of male engagement, in their final evaluation reports, with most indicating approval of male engagement to promote or support EBF. Only one comment considered having male volunteers speak with mothers about breastfeeding techniques as potentially inappropriate (American Red Cross, Cambodia). The final evaluator for Care’s project in Sierra Leone noted that the concerted effort during project planning to include household decision-makers (men and older women) in the project approaches contributed to the adoption of positive health behaviors among women, which was revealed by women in project focus group discussions.

With increased emphasis on male involvement in the reproductive health care and decisions in global health, it is important to understand where engaging men as a social and behavior change approach, broadly speaking, may support EBF practice and if it could hinder it. This study provided a mainly descriptive review of strategies, and we conclude that, unlike peer support, professional support in the antenatal and postpartum periods, and other evidence-based strategies [8], engaging men in EBF promotion and support has had mixed results and appears to be highly dependent on context. Thus, it cannot be assumed to be appropriate or effective everywhere. There is evidence of its success in some contexts, both high- (e.g., [15]) and low-income (e.g., [21]), but local gender factors related to decision-making, power, autonomy, and what is considered “women’s space” should be understood before “engaging men” is adopted as a general approach. In addition, most projects that reported a male engagement strategy also reported engaging women (mothers and grandmothers) alongside men (Table 2), making it difficult to disentangle the approaches. We do not know if strategies to engage men alone would have had a different impact on EBF prevalence in these areas.

One cannot consider male engagement in women’s health issues without considering the gender norms that govern relationships in households and communities. Less than one-quarter of these projects reported using formative research to inform their strategies (Table 2). Formative research would enable the opportunity to investigate gender norms in order to create an appropriate intervention that is gender-sensitive and could, in some circumstances, be gender transformative [25]. This type of formative research could also inform a project-wide gender and social and behavior change strategy. Whereas decisions about health care often involve money for travel and services, and money is often under the jurisdiction of male authority, decisions about infant care are often left to mothers themselves. Some societies have deeply embedded cultural beliefs about the gendered division of family responsibilities, with men focusing on financial matters and women focusing on household matters, even when those women work in the formal sector or outside of the home, as documented by Nkwake [26] in Uganda. Taking care of the family, deference to men, and inequality with men at home and in public are gender norms that form a “model of domestic virtue,” which has persisted over the past century [27]. Likewise, in Benin, there is evidence of persistent gender disparities regarding access to and control of resources, and men often make decisions related to health care [28]. Where women’s movements are restricted or require male permission, as documented in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan [29–33], they may not be able to access or provide peer breastfeeding support, which has been shown to reduce suboptimal breastfeeding practices [8].

The impact of gender norms on women’s infant feeding practices is not well understood. Meanwhile, there is some evidence that high rates of child stunting (low height for age) can co-exist with relatively high values for positive indicators of child health, such as immunization coverage [34]. Stunting reflects both mothers’ and children’s health status; where women have little autonomy, are deprived of their rights to education and health, and are forced into early marriage, their health is negatively affected [35–37], and thus, the health of their children is negatively affected.

There is evidence of male, specifically fathers’ , influence on infant feeding practices [10, 38]. We found some evidence of this in project reports; at least one evaluator cited male decision-making authority in household matters. A study about engaging men to reduce malnutrition in Mozambique found that men were primary influencers for exclusive breastfeeding [39]. The influence of other household actors was not examined in this study but has been shown to influence infant feeding, particularly mothers-in-law (infants’ grandmothers) [40, 41]. The influence of other household actors could confound the association between fathers and EBF. The role and influence of different household actors should be considered when planning EBF promotion and support activities as they may present barriers, or even enabling factors, to achieving the goals of the activities.

Conceptual theory about male engagement in EBF promotion and support is not well developed, and we do not know if the reported male engagement strategies effectively engaged men. We did not attempt an advanced quantitative assessment of the association of male engagement strategies with EBF prevalence changes but merely report those associations as part of our descriptive approach to documenting efforts to engage men in EBF promotion and support in LMIC. National or local campaigns to increase EBF may have contributed to prevalence changes in project areas, although we did not find evidence of such efforts in the project final evaluation reports. Nonetheless, we were careful not to ascribe EBF prevalence increase to these projects’ efforts. All project final evaluation reports were program evaluations and not impact evaluations; therefore, the true extent of the impact of the strategies to engage men is unknown beyond the conclusions drawn in the reports. We did not specifically examine or describe how male engagement strategies could have a detrimental effect on EBF practice nor where male involvement in infant feeding decisions reinforces gender inequality, but these questions merit further research.

If considering implementation on a national scale, it would be important to evaluate the effectiveness of male engagement strategies and conduct multiple tests in different areas to determine if strategies are scalable. More comparative studies and impact evaluations are needed within countries to determine which strategies are most effective at promoting and supporting EBF with different populations. Contextual information about societal dynamics can indicate where and with whom interventions are most efficiently targeted [40]. Specifically, more studies about the effect of male engagement on breastfeeding practices are needed, including formative research about male involvement in decisions regarding infant feeding and women’s desire for male involvement in breastfeeding promotion and support.

Conclusion

It is important to understand the association between gender norms, male engagement strategies, and EBF prevalence in different contexts. This study augments the literature on this topic by reviewing an array of strategies that have been used in different LMIC. Together, these studies point to the importance of formative research about local gender norms and power structures to inform interventions. With increased emphasis on male involvement in reproductive health care and decisions in different settings, the question of for whom to focus promotion messages and supportive skills merits further research in order to determine the most appropriate and effective way to support EBF.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the late Miriam Labbok MD, MPH, IBCLC, who advised previous studies related to these data. Rob Carty assisted with formatting the figures. Dr. Paige Hall Smith, Director of the Center for Women’s Health and Wellness and Associate Professor at UNC Greensboro gave advice regarding relevant literature. We thank the NGOs who work to increase EBF practice in many countries, and we thank the mothers for giving so much of themselves to this world.

Funding

JY was funded in part by the NIH Training Program in Reproductive, Perinatal, and Pediatric Epidemiology (T32-HD52468). This funding source had no role in the design of the study, nor in the analysis and interpretation of data, nor in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSHGP

Child Survival and Health Grants Program

- EBF

Exclusive breastfeeding

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LAM

Lactational amenorrhea method

- LMIC

Low- and middle-income countries

- NGO

Nongovernmental organization

- USAID

United States Agency for International Development

Authors’ contributions

JY designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the quantitative data, and drafted the manuscript. JA extracted and analyzed the qualitative data and provided substantive input to the manuscript. DP created figures and provided background research and substantive input to the manuscript. JT provided substantive input to the manuscript and advised the analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

The University of North Carolina’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study was not human subject research and does not require IRB approval. It is an analysis of secondary data (project reports) with no personal identifiers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jennifer M. Yourkavitch, Phone: 919-869-7645, Email: yourkavi@live.unc.edu

Jeniece L. Alvey, Email: jeniecealvey@gmail.com

Debra M. Prosnitz, Email: Debra.prosnitz@icf.com

James C. Thomas, Email: jim.thomas@unc.edu

References

- 1.Kraft JM, Wilkins KG, Morales GJ, Widyono M, Middlestadt SE. An evidence review of gender-integrated interventions in reproductive and maternal-child health. J Health Commun. 2014;19(Suppl 1):122–141. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.918216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhar R, editor. Against all odds: gendered challenges to breastfeeding. Malaysia and Costa Rica: World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action and Centro Feminista de Información y Acción; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Exclusive breastfeeding for six months best for babies everywhere. 2011. Accessed 12 May 2017. (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/).

- 4.Black R, Allen L, Bhutta Z, Caulfield L, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. (Maternal and Child Undernutrition series 1) Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360:187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Victora C, Horta B, de Mola L, Quevedo L, Pinheiro R, Gigante D, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e199–e205. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding Medicine Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, Buchanan P, Taylor JL, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fjeld E, Siziya S, Jatepa-Bwalya M, Kankasa C, Moland KM, Tylleskar T. ‘No sister, the breast alone is not enough for my baby’ a qualitative assessment of potentials and barriers in the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in southern Zambia. Int Breastfeed J. 2008;3:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Escamilla R, Lutter C, Segall AM, Rivera A, Trevino-Siller S, Sanghvi T. Exclusive breastfeeding duration is associated with attitudinal, socioeconomic and biocultural determinants in three Latin American countries. J Nutr. 1995;125:2972–2984. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.12.2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otoo GE, Lartey AA, Perez-Escamilla R. Perceived incentives and barriers to exclusive breastfeeding among periurban Ghanaian women. J Hum Lact. 2009;25:34–41. doi: 10.1177/0890334408325072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezner KR, Laifolo D, Shumba L, Msachi R, Chirwa M. ‘We grandmothers know plenty’: breastfeeding, complementary feeding and the multifaceted role of grandmothers in Malawi. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1095–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguiar C, Jennings L. Impact of male partner antenatal accompaniment on perinatal health outcomes in developing countries: a systematic literature review. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:2012–2019. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bar-Yam N, Darby L. Fathers and breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Hum Lact. 1997;13(1):45–50. doi: 10.1177/089033449701300116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbass-Dick J, Stern SB, Nelson LE, Watson W, Dennis C. Co-parenting breastfeeding support and exclusive breastfeeding: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):102. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown A, Davies R. Fathers’ experiences of supporting breastfeeding: challenges for breastfeeding promotion and education. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(4):510–526. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell-Box K, Braun K. Impact of male-partner-focused interventions on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and continuation. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(4):473–479. doi: 10.1177/0890334413491833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tohotoa J, Maycock B, Hauck Y, Howat P, Burns S, Binns C. Dads make a difference: an exploratory study of paternal support for breastfeeding in Perth, Western Australia. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maycock B, Binns CS, Dhaliwal S, Tohotoa J, Hauck Y, Burns S, et al. Education and support for fathers improves breastfeeding rates: a randomized controlled trial. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(4):484–490. doi: 10.1177/0890334413484387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bich T, Hoa D, Malqvist M. Fathers as supporters for improved exclusive breastfeeding in Viet Nam. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1444–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Özlüses E, Çelebioglu A. Educating fathers to improve breastfeeding rates and paternal-infant attachment. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(8):654–657. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Susin L, Giugliani E. Inclusion of fathers in an intervention to promote breastfeeding: impact on breastfeeding rates. J Hum Lact. 2008;24:386. doi: 10.1177/0890334408323545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MCHIP. Knowledge, practice and coverage survey resources. 2014. Accessed 12 May 2017. (https://www.mcsprogram.org/resource/knowledge-practice-coverage-tool/).

- 25.Dworkin S, Fleming P, Colvin C. The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: critical reflections from the field. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(S2):S128–S143. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nkwake A. Maternal employment and fatherhood: what influences paternal involvement in child-care work in Uganda? Gend Dev. 2009;17(2):255–267. doi: 10.1080/13552070903009726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyomuhendo G, McIntosh M. Women, work and domestic virtue in Uganda, 1900–2003. Cumbria: Long House Publishing Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Bank. 2002. Strategic country gender assessment. Benin. Accessed 12 May 2017. (http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/135131468003936000/pdf/393300BN0Strategic0Gender01PUBLIC1.pdf).

- 29.OECD Development Center. Social Institutions and Gender Index. Accessed 10 Feb 2017. (http://www.genderindex.org/country/liberia).

- 30.OECD Development Centre. Social Institutions and Gender Index. Accessed 11 Feb 2017. (http://www.genderindex.org/country/sierra-leone).

- 31.CARE. 2015. Nepal: Gender relations in Nepal overview. Accessed 12 May 2017. (http://www.care.org/sites/default/files/documents/RGA%20Overview%20Nepal_Final.pdf).

- 32.Balk D. Defying gender norms in rural Bangladesh: a social demographic analysis. Popul Stud. 1997;51(2):153–172. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000149886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.OECD Development Centre. Social Institutions and Gender Index. Accessed 11 Feb 2017. (http://www.genderindex.org/country/afghanistan).

- 34.Burgert-Brucker CR, Yourkavitch J, Assaf S, Delgado S. Geographic variation in key indicators of maternal and child health across 27 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. DHS spatial analysis reports no. 12. ICF International: Rockville; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Root GPM. Disease environments and subnational patterns of under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Popul Geogr. 1999;5:117–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199903/04)5:2<117::AID-IJPG127>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woldemicael G, Tenkorang EY. Women’s autonomy and maternal health-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):988–998. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raj A. When the mother is a child. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:931–935. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.178707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engebretsen IMS, Moland K, Nankunda J, Karamagi CA, Tylleskar T, Tumwine JK. Gendered perceptions on infant feeding in eastern Uganda: continued need for exclusive breastfeeding support. Int Breastfeed J. 2010;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Men Care. Engaging men as gender-equitable fathers and caregivers to reduce malnutrition in Mozambique. 15 November 2016. Accessed 11 Feb 2017. (http://men-care.org/2016/11/15/engaging-men-gender-equitable-fathers-caregivers-reduce-malnutrition-mozambique/).

- 40.Aubel J. The roles and influence of grandmothers and men: evidence supporting a family-focused approach to optimal infant and young child nutrition. Washington, DC: IYCN Project; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grassley J, Eschiti VS. Two generations learning together: grandmothers’ support of breastfeeding. Int J Childbirth Educ. 2007;22(3):23–26. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.