Abstract

Parenting behaviors influence clinical depression among youth, but little is known about the developmental processes that may account for this association. This study investigated whether parenting is associated with the onset of clinical depression and depressive symptoms through negative cognitive style, particularly under conditions of high exposure to stressors, in a community sample of children and adolescents (N = 275; 59% girls). Observational methods were used to assess positive and negative parenting during a laboratory social-evaluative stressor task. Depressive symptoms and clinical depressive episodes were repeatedly assessed over an 18-month prospective follow-up period. Results supported a conditional indirect effect in which low levels of observed positive parenting during a youth stressor task were indirectly associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing an episode of depression and worsening depressive symptoms over the course of the study through youth negative cognitive style, but only for youth who also experienced a high number of peer stressors. These findings elucidate mechanisms through which problematic parenting may contribute to risk for the development of clinical depression during the transition into and across adolescence. Implications for depression interventions are discussed.

Theory and research on the etiology of depression have increasingly focused on the role of family environments, particularly parenting factors, in the development of child and adolescent depressive symptoms and disorders (Sheeber, Hops, & Davis, 2001; Schleider & Weisz, in press). Specifically, evidence suggests that exposure to low levels of positive, supportive parenting, and high levels of negative parenting, is associated with increased risk for depression (Sheeber et al.). However, very little is known about the developmental mechanisms through which parenting behaviors may influence the etiology of depression. One possibility is that low positive parenting contributes to the development of negative cognitive distortions, or cognitive vulnerability for depression (Sheeber et al.). Considerable evidence supports cognitive vulnerability as a prospective predictor of depression among adults, adolescents, and children (Abela & Hankin, 2008).

Exposure to stressors, in addition to parenting, is another widely hypothesized environmental risk factor in the development of cognitive vulnerability (Garber & Flynn, 2001; Hamilton, Stange, Abramson, & Alloy, 2015; Hankin et al., 2009). Furthermore, the inferential feedback hypothesis proposes that parenting behaviors that implicitly or explicitly convey negative information about stressors are especially influential in the formation of cognitive vulnerability (Alloy et al., 2001). Thus, it is implicit in the inferential feedback hypothesis that youth who receive problematic parenting when faced with stressors, and also experience a high number of stressors (e.g., peer stressors), are at especially high risk for developing cognitive vulnerability, which in turn leads to increased risk for depression (Mezulis, Hyde, & Abramson, 2006).

The transition into adolescence, particularly the emergence of puberty, initiates a cascade of physical, hormonal, psychological, and social changes, which may set the stage for increased depression risk (Ladouceur, Peper, Crone, & Dahl, 2012). First, this period is characterized by transformations in parent-child relationships (e.g., increase in parent-child conflict) as youth strive for greater autonomy from parents (Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998). Second, youth experience an increase in stressors, including peer-related stressors, which coincides with the increase in importance of peer relationships (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007). Third, as self-concept and beliefs about self-competency stabilize during the transition into adolescence, there is evidence that cognitive vulnerability may also emerge during this time (Cole et al., 2001). In particular, findings suggest that negative cognitive style, one type of cognitive vulnerability, becomes more trait-like around late middle childhood and early adolescence (Hankin, 2008). The onset of puberty is also closely linked to a rise in rates of depression. Specifically, levels of depression, both symptoms and disorder, are higher among postpubertal, compared to prepubertal youth (Angold, Worthman, & Costello, 2003; Ge & Natsuaki, 2009; Rudolph, 2014). Thus, the transition into and across adolescence is a critical developmental period for understanding how the interplay between parenting and stressors may contribute to cognitive vulnerability and increased risk for depression.

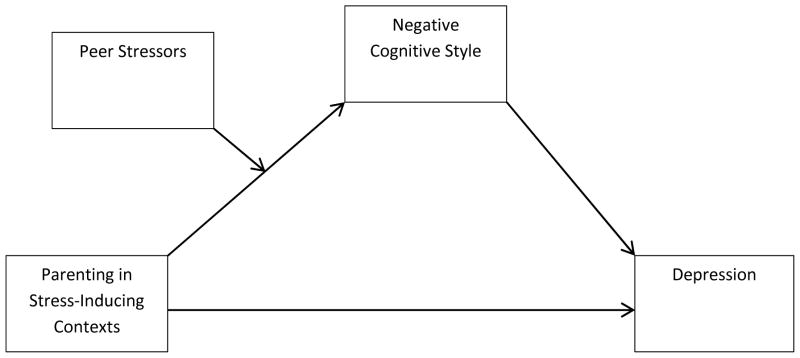

Despite normative shifts occurring within parent-child relationships during adolescence, parents continue to be important for youth adjustment (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Previous studies further suggest that positive, supportive interactions with parents are useful in protecting against the detrimental impact of rising peer stressors before, during, and after the transition into adolescence (Hazel, Oppenheimer, Technow, Young, & Hankin, 2014; Oppenheimer et al., 2016). The goal of the current study was to investigate whether parenting might influence depressive symptoms and onsets of clinical depression through cognitive vulnerability, particularly among youth exposed to high levels of peer stressors, despite the considerable changes transpiring within parent-child relationships from middle childhood into adolescence. Specifically, this study tested the hypothesis that low positive and high negative parenting behaviors, observed during a social-evaluative laboratory stressor task for youth, would relate to a negative cognitive style for those youth exposed to a higher number of peer stressors, and that a negative cognitive style in turn would predict increases in depressive symptoms and the onset of a clinically significant depressive episode over an 18-month period (i.e., we hypothesized a conditional indirect effect of parenting on clinical depression; see Figure 1). We tested this hypothesis in a sample of youth spanning the transition into adolescence, which included youth from middle childhood (i.e., pre-pubertal transition) into late adolescence (i.e., post-pubertal transition).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model in which the indirect effect of parenting on youth clinical depression is moderated by peer stressors. Negative cognitive style is the proposed intervening variable of the conditional indirect effect of parenting on youth depression.

Cognitive vulnerability and Depression

Cognitive theories of depression posit that biases in the way an individual perceives, interprets, and remembers negative information contributes to the development of depression (Beck, 1976). Hopelessness theory (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989) emphasizes the role of negative cognitive style in depression, which is described as the tendency to 1) make negative inferences about the causes of negative events (stable, global attributions), 2) catastrophize about the consequences of negative events, and 3) infer negative characteristics about the self following negative events. Negative cognitive style is thought to be a relatively stable and habitual way of interpreting the meaning of negative life events, and has received a great deal of attention as one of the central cognitive vulnerabilities to depression (Hankin, Snyder, & Gulley, 2016). Considerable evidence with prospective designs shows that this cognitive risk predicts later increases in depressive symptoms and clinical depression among youth (Hankin et al.). The current study explores negative cognitive style as one possible mechanism through which parenting, in interaction with stressors, may influence depressive symptoms and clinical depression.

Parenting and Associations with Cognitive Vulnerability and Depression

Despite some changes in the parent-child relationship, research suggests that parents continue to be a major source of influence and support during adolescence (Steinberg, 2001). Importantly, parents have been shown to play an essential role in the development of depression: adolescents who have more supportive, positive relationships with parents are at a decreased risk for depressive symptoms and clinical levels of depression (Seeley, Stice, & Rohde, 2009, Sheeber, Davis, Leve, Hops, & Tildesley, 2007), whereas youth exposed to low levels of support and positive parenting from parents are at greater risk for depression (see review by Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb, & Neeren, 2006).

A growing body of literature suggests that parenting behaviors may influence the development of depression through the formation of cognitive biases as youth learn to process information about the self and their experiences through interactions with their parents (Sheeber, Hops, & Davis, 2001). A number of studies have used self-report questionnaire methods to examine the association between parenting and cognitive vulnerability. These studies show that youth who experience low levels of warmth and approval from parents, and/or high levels of parental rejection and criticism, are more likely to develop a poor self-image and a negative cognitive style (Alloy et al., 2001; Garber & Flynn, 2001; Ingram, Overbey, & Fortier, 2001; Ingram & Ritter, 2000). Only a small handful of studies have linked parenting, cognitive vulnerability, and depression together in one model to test whether parenting influences depression through cognitive vulnerability among youth (Alloy et al., 2001; Liu, 2003; Randolph & Dykman, 1998; Whisman & Kwon, 1992). Using self-report questionnaires, these investigations show that low levels of positive parenting contribute to depression via cognitive vulnerability, including negative cognitive style.

Parenting in the Context of Stressors

A number of studies suggest that relationships with parents characterized by positive qualities protect against youth depressive symptoms when children and adolescents are faced with stressors (Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994; Ge, Natsuaki, Neiderhiser, & Reiss, 2009; Hazel, et al., 2014; Natsuaki et al., 2007), perhaps by contributing to more adaptive appraisals of negative events (Alloy et al., 2001). This suggests that parental behaviors may convey information about the meaning of negative experiences and stressors in a way that contributes to cognitive vulnerability for depression, consistent with the inferential feedback hypothesis (Alloy et al., 2001; Crossfield, Alloy, Gibb, & Abramson, 2002).

It is especially crucial to understand how parenting behaviors relate to youth cognitive response to stress during the transition into adolescence when an increase in stressors, especially peer stressors, during this developmental period may tax the ability for youth to independently and effectively respond to stress (Hankin et al., 2007; Yap, Allen, & Sheeber, 2007). Peer stressors are also a powerful predictor of depressive symptoms during adolescence (Hankin et al., 2007; Rudolph, Flynn, Abaied, Groot, & Thompson, 2009) as youth experience more frequent interactions with peers (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987), an expansion of peer networks (Prinstein & La Greca, 2002), and greater intimacy within close friendships (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). There is also growing evidence that parenting behaviors interact with peer stressors, more so than other types of stressors, to predict youth outcomes during the transition into adolescence. Oppenheimer et al., (2016) recently found that positive parenting protected against emotional reactivity to peer, but not non-peer, negative events among anxious youth across the transition into adolescence. Similarly, Hazel and colleagues (2014) showed that low positive relationships with parents protected against depressive symptoms when youth encountered high levels of peer stressors, but not non-peer stressors, across the adolescent transitional period. It is important to note that the category of non-peer stressors in these studies was a broad and included a range of other types of stressors in the domains of health, finance, academics, and family. Thus, it is unclear from these findings whether positive parenting may also buffer against other types of social stressors, such as family stressors, given that family stressors have also been linked to increases in youth depressive symptoms (Epkins & Heckler, 2011; Hamilton et al., 2016). However, Mezulis et al. (2006) found that high levels of negative parenting more consistently predicted negative cognitive style among children and early adolescents exposed to peer stressors compared to other types of stressors, including family stressors. Therefore, youth interactions with parents may be particularly important for the development of cognitive interpretations in response to other social stressors that occur outside the family, such as peer stressors, during the transition into adolescence. Given the limited research exploring how parenting may be associated with cognitive vulnerability in the context of various types of youth stressors (social and non-social), we explored this research question in more detail by examining whether parenting interacted with family stressors, in addition to peer and non-peer stressors, in this study.

Limitations of Prior Research

Research examining the effects of parenting and stressors on cognitive vulnerability and risk for depression is limited in important ways. First, only a small handful of studies have examined cognitive vulnerability as a mechanism through which parenting may influence depression, and all of these studies have assessed parenting using self-report questionnaires. The use of self-reports only to assess parenting is limited given that multiple meta-analyses have found that the method used to assess parenting moderates the effect of parenting on child outcomes, including child depression (McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007; McLeod, Wood, & Weisz, 2007; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994). Questionnaire methods to assess parenting are limited for several reasons: 1) shared method variance can inflate associations, 2) depressed individuals’ biased perceptions can lead to overreporting of negative behaviors on questionnaires (Najman et al., 2000; Rudolph & Clark, 2001), and 3) parenting questionnaires typically measure global, decontextualized constructs that aggregate information across time and situations (Holden & Edwards, 1989). Although a more global, self-report assessment can provide useful, complementary information about parenting behaviors, observational methods can assess parenting in more specific contexts in a more objective way. Therefore, this study seeks to advance research on cognitive vulnerability as an intervening mechanism through which parenting may influence depression by using observational methods to assess parenting. Specifically, we assess parenting within a stress-inducing context to more precisely measure how parents respond to youth during socially relevant stress. Recent studies have shown that parenting during a similar social-evaluative stressor task is associated with risk for youth mood disorders, and buffers against peer (but not non-peer) negative events (Oppenheimer et al., 2016; Silk et al., 2013).

Second, the inferential feedback hypothesis suggests that parenting may be more likely to influence the development of cognitive vulnerability in the context of stress. Thus, it follows that parenting may be more likely to influence cognitive vulnerability, which in turn may influence the development of depressive symptoms and clinical depression, when youth are exposed to a high number of stressors. Two studies to our knowledge have investigated this interaction effect on cognitive vulnerability, and have found support for the influence of parenting (including observed parenting) on cognitive vulnerability under conditions of high stressors (Crossfield et al., 2002), particularly peer stressors (Mezulis et al., 2006). This study seeks to build on these studies by testing whether exposure to peer stressors moderates the indirect effect of observed parenting on depression through cognitive vulnerability (conditional indirect effect, see Figure 1). In other words, we investigated whether parenting is associated with depression related outcomes through cognitive vulnerability, when youth have encountered a high level of peer stressors.

Finally, the majority of prior studies investigating cognitive vulnerability factors as a mechanism through which parenting influences depression have not examined clinically significant episodes of depression (Alloy et al., 2006). The two studies that did examine onsets of a clinical depressive disorder when investigating cognitive vulnerability as a mediator of the association between self-reported parenting and depression used college samples of young adults (Alloy et al., 2001; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2002). Therefore, it is unclear whether findings showing that parenting influence depressive symptoms through cognitive vulnerability generalize to clinically significant levels of depression across the transition into and through adolescence, when youth are particularly vulnerable to developing clinical depressive episodes. In line with these studies of young adults, we expected that parenting (in interaction with stressors) would predict both clinical depression and depressive symptoms through cognitive vulnerability among children and adolescents. In this study, repeated semi-structured diagnostic interviews at 6-month intervals and repeated measures of depressive symptoms were used to ascertain the onset of a depressive episode and changes in depressive symptoms among youth over an 18-month period.

We hypothesized that youth who tend to receive low levels of positive parenting or high levels of negative parenting in the context of experiencing stress, and who also were exposed to high levels of peer stressors, would be more likely to have a general negative cognitive style, and in turn, this cognitive vulnerability would be associated with increases in depressives symptoms and a clinically significant depressive episode. We also explored whether youth who receive low positive parenting or high negative parenting parenting are also more likely to develop a negative cognitive style when faced with high levels of family stressors, given that this is another type of important social stressor.

Method

Participants

Children and adolescents were recruited by brief information letters sent home directly by the participating school districts to families with a child in public school. Approximately 2,000 families had a child in 3rd, 6th, or 9th grade in a participating school district, and therefore were eligible to receive letters. The letter stated that we were conducting a study on social and emotional development in children and adolescents and requested that interested participants call the laboratory to receive more detailed information. Approximately 400 families contacted the laboratory, and about 87% of these qualified as study participants and were enrolled in the study. The remaining 13% families were considered non-participants for the following reasons: Over 95% of families chose not to participate after hearing about study requirements or agreed to participate but then did not arrive for scheduled appointments, 1% were excluded because the parent reported their child had an autism spectrum disorder, and 3% were excluded because they were non-english speaking families. Participants for this study included 275 youth ranging in age from 7 to 17 (M = 12.80, SD = 2.40) who completed all baseline measures and diagnostic clinical follow-up interviews.. The sample was approximately evenly divided by sex (59% girls). The present sample, drawn from the general community of youth attending public schools, was representative of both the broader population of the geographical area and the school districts from which the sample was drawn, including socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and race. Ethnicity was as follows: Caucasian, 70%; African American, 5%; Latino, 7%; Asian/Pacific Islander, 4%; other/mixed ethnicity and race, 14%. Parents of the youth were predominantly mothers (85%). Median annual family income was $78,500 and 20% of the youth received free/reduced lunch at school.

Procedure

The parent and youth visited the laboratory for their baseline assessment. Parents provided informed written consent for their participation and for their child; youth provided written assent. During the baseline assessment, parents and youth completed a battery of questionnaires, and parents provided information about basic demographics. Youth participated in a psychosocial laboratory challenge while parents were present, and parent-child interactions were videotaped during this task. Additionally, youth and their parents were administered a semi-structured diagnostic interview to assess for youth depression.

Regular follow-up assessments were conducted every 6 months over the phone over a year and a half period (four waves of data) to assess youth clinical depression and depressive symptoms.

Measures

Parenting behaviors during stressor task

Parenting behaviors were observed and coded during the videotaped 5 minute youth psychosocial challenge. During this task, youth were instructed to pretend to audition for a reality television show about kids, and were told that their speeches would be evaluated by judges. Youth then gave a speech to the camera for 2 minutes about why they should be chosen for the show. Parents sat behind the child during the speech, and were told that although the speech was for the child to perform, they could provide support as needed. After the youth completed the speech, a research assistant came into the room and told that parent and child that they were free to talk while the speech was viewed and scored by judges. Youth and the child were then left alone for another 3 minutes during this time. Youth and parents were debriefed at the end of the assessment period about the stressor task. During the debriefing, they were told that the task was designed to help understand different ways people respond to stress and that their speeches would not be evaluated.

Positive parenting and negative parenting were coded by independent raters throughout the entire 5 minutes of the videotaped psychosocial challenge. One global code was given for each parenting construct on a scale between 1 and 5 (1 = not at all characteristic of parent behavior during interaction and 5 = highly characteristic of parent during interaction). Parenting observational codes reflect theoretically grounded dimensions of positive and negative parenting considered most relevant for depression in youth (i.e., reflect parental warmth/approval, and parental rejection/criticism; Alloy et al., 2001; Shleider & Weisz, in press). Parents who exhibited high levels of positive parenting demonstrated genuine affection, praise, and enthusiasm towards their child throughout the interaction. Specifically, these parents exhibited warm and enthusiastic tone of voice while communicating frequent expressions of praise and approval (e.g., “you did great!”). Similar codes, also referred to as parent “warmth” or “positive regard”, have been used in previous studies to assess these features of positive parenting (Chi & Hinshaw, 2002; Davidov & Grusec, 2006). Parents who exhibited high levels of negative parenting demonstrated more frequent and intense expressions of disapproval, criticism, or abruptness towards their child in a negative tone of voice (e.g., “don’t do that”, or “that wasn’t smart”). Previous studies have also used similar codes to assess these aspects of negative parenting, also termed “criticism”, “hostility”, or “negative regard” (Corona, Lefkowitz, Sigman, & Romo, 2005; Melby & Conger, 1998).

An initial training session was held to teach raters the coding system. Raters then coded two to three practice tapes at a time and met weekly to discuss discrepancies. In this way, raters were trained to reliability until intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of .70 or greater were established with the criterion rater. Once reliability was obtained, approximately 20% of cases were double coded, and the remaining cases were single coded by the reliable, trained raters. Final ICCs across pairs of coders ranged from .91 to .95 for positive parenting and .81 to .86 for negative parenting.

Stressors

Eight items from the Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire (ALEQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002) identified a priori as having to do with peer relationships (e.g., “Feeling pressure by friends”, “Fighting with or problems with a friend”, “Friend is criticizing you behind your back”) were summed to form a scale of peer stressor exposure. Each item was rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always) reflecting how often that experience had happened to the participant in the last 3 months. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 32 for this scale. Internal reliability for this scale was α = .76. The remaining 29 items from the ALEQ were summed to form a scale of non-peer stress, which included a range of types of stressors, including family stressors (e.g., “Getting bad grades on progress reports”, “Death of a relative”, “Financial troubles or money problems”). Internal reliability for this scale was α = .88. The broader ALEQ been widely used in previous longitudinal studies on multiple continents (e.g., Abela et al., 2011; Calvete, Orue, & Hankin, 2012; Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010), and the peer and non-peer stressor subscales have also been used previously (Hazel et al., 2014). These data show the ALEQ to be a reliable and valid predictor of prospective elevations in depressive symptoms in children and adolescents as young as 3rd grade (Hankin, Jenness, Abela, & Smolen, 2011).

In this study, we also compared findings with peer stressors to family stressors, another specific type of social stressor. Eight items from the Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire (ALEQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002) identified a priori as having to do with family relationships (e.g., arguments or fights between parents, “problems or arguments with parents, siblings, or family members”, “not getting along with parents” ) were summed to form a scale of family stressor exposure. Each item was rated on a scale from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“always”) reflecting how often that experience had happened to the participant in the last 3 months. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 32 for this scale, and internal reliability was α = .76.

Negative cognitive style

The Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire (ACSQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002) was used to measure inferences about negative events. The ACSQ presents the adolescent with negative hypothetical events in achievement and interpersonal domains and asks the youth to make inferences about the causes about the event (internal– external, stable–unstable, and global–specific), consequences of the event, and characteristics about the self. The ACSQ has demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability, good test–retest reliability, and a factor structure consistent with hopelessness theory (i.e., separate factors for inferences about causes, consequences, and self-characteristics; Hankin & Abramson, 2002). Each item dimension is rated from 1 to 7. Average item scores on the ACSQ were used in this study, with higher scores indicating a more negative cognitive style. Internal consistency in this sample was α = .91.

Depression diagnoses

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version (KSADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997) was used to assess for the presence of a DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of depression. The KSADS is the most frequently used, most studied diagnostic interview with youth and has demonstrated strong evidence of reliability and validity (Kaufman et al., 1997; Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005). Diagnostic interviewers completed an intensive 40 hour training program for administering the KSADS interview and for assigning DSM-IV diagnoses. At baseline, the youth and their parent were interviewed for a lifetime history of depression and for a current depressive disorder. In addition, both parent and youth were interviewed at every follow-up for a depressive episode that occurred any time during the 6 month period following the last assessment. Interviewers determined youths’ diagnostic status using best estimate diagnostic procedures (Klein et al., 2004). Discrepancies were reconciled using consensus meetings and clinical judgment, with the interviewer integrating what was reported by the child and parent to arrive at a diagnosis judgment that best captures an accurate portrayal of the child’s mental health. Youth participants were deemed to have a depressive episode if they met DSM-IV criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Definite, MDD-Probable (four threshold depressive symptoms with at least 2 weeks duration), minor Depressive Disorder (mDD) Definite (two or three threshold depressive symptoms with at least 2 weeks duration), or dysthymic depressive episode. We based the decision to combine these diagnoses into a single variable on prior evidence showing that depression is dimensionally distributed at the latent level (Hankin, Fraley, Lahey, & Waldman, 2005) and that these various depression diagnoses (i.e., MDD Definite, MDD Probable, and mDD Definite) all are associated with significant distress, impairment, and psychosocial problems (Avenevoli, Swendsen, He, Burstein, & Merikangas, 2015; Gotlib, Lewinsoh, & Seeley, 1995). Inter-rater reliability for the K-SADS, based on 15% of the sample interviews (n=55) was good (kappa = .91). A dichotomous variable was then calculated to use as our overall measure of youth clinical depression. Specifically, youth were given a score of 0 if they never had a depressive episode over the course of the 18 month study (no current episode at baseline, and no episodes at any follow-ups), or a 1 if they met criteria for one or more episodes of depression over the course of the study (a current episode at baseline, or an episode at any of the follow-ups). Youth that endorsed a past history of depression but did not endorse any depressive episodes during the course of the study received a score of 0 (i.e., were classified as non-depressed), because we were interested in only predicting depressive episodes that occurred over the 18 month course of the study.

Depressive symptoms

Youths’ reports of depressive symptoms were assessed using the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 2003), a well-established measure of broad depressive symptoms in youth. The CDI asks about depressive symptoms within the past two weeks. Each of the 27 items was scored on a scale of 0 to 2, resulting in scores ranging from 0 to 54. The CDI is one of the most commonly used, reliable, and valid measures of depressive symptoms among youth (Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005) and it has been demonstrated to be a valid indicator of depressive symptoms and shows measurement invariance across adolescents both with and without major depressive disorder (Gomez, Vance, & Gomez, 2012). For this study, we examined CDI scores at baseline, 6 month follow-up, and 18 month follow-up. α’s ranged from .80 to .87 across time points.

Puberty status

Youth were administered the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen et al., 1988), which includes five questions about physical development, scored from 1 (no) to 4 (development complete). Reliability and validity of the PDS is high (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988; Shirtcliff, Dahl, & Pollak, 2009), as PDS scores relate significantly with physical examination for pubertal development (Shirtcliff et al.). We followed standard PDS scoring to create prepubertal and postpubertal groups separately for girls and boys. Internal reliability for this sample was α = .83.

Overview of Statistical Approach

The SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2013) was used to test the hypothesized model (see Figure 2 for model in path diagram form). PROCESS was chosen for its ability to easily test a conditional indirect effect within a single, unified model. PROCESS uses a regression based path-analysis and bootstrapping procedures, consistent with modern approaches to testing indirect and conditional indirect effects recommended by quantitative methodologists (Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009; Hayes)

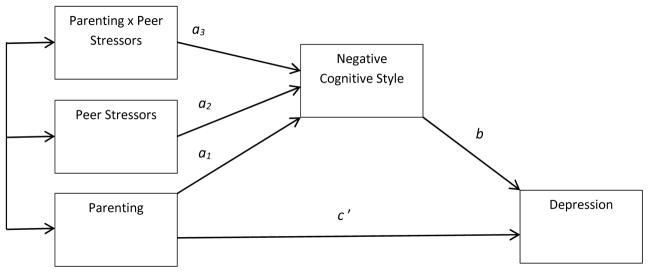

Figure 2.

The conceptual model in Figure 1 represented in the form of a path model corresponding to the regressions estimated and reported in Tables 4a and 4b.

Using path analysis, the components of the model are used to calculate the conditional indirect effect, which addressed our primary research question of whether parenting is associated with youth depression related outcomes through youth negative cognitive style, and if this indirect effect is moderated by youth exposure to peer stressors. The first component of the hypothesized model estimates whether the effect of parenting on cognitive style is moderated by exposure to peer stressors, controlling for main effects (See path a3, Figure 2). Second, path b in the model estimates the association between cognitive style and clinical depression after controlling for parenting. Third, path c’ estimates the direct effect in this model, which is the association between parenting and depressions controlling for cognitive style. Finally, the total effect is the association between parenting and depression, without controlling for cognitive style or other variables (c; not pictured).

The indirect effect is estimated by multiplying a1 by b. Therefore, the conditional indirect effect was estimated in the current analyses as (a1 + a3stressors)b, where stressors are the moderating variable. A 95 percent bias-corrected bootstrapping confidence interval based on 10,000 bootstrap samples was ccalculated to determine the significance of the indirect effect. The same models were tested separately for each parenting variable (positive and negative parenting), and for each type of stressor (peer, non-peer, and family stressors). All continuous predictor variables were centered to reduce multicollinearity.

Analyses predicting clinical depressive episodes and baseline depressive symptoms included youth who completed baseline measures and follow-up diagnostic clinical interviews (N =275). Analyses predicting depressive symptoms at 6 months and 18 months included those youth who also completed the CDI at the 6 month-follow up (N = 260) and 18 month follow-up (N = 246) respectively, in addition to baseline measures and diagnostic interviews.

We tested whether significant findings held after controlling for gender, age, and pubertal development, given that these variables are correlated with increases in depression.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations for primary continuous variables are presented in Table 1. Of note, peer, family, and non-social stressors were significantly correlated with negative cognitive style, and with depressive symptoms at baseline, 6-months, and 18-months. Positive parenting was negatively associated with depressive symptoms at 6-months and 18-months. Age was positively associated with negative cognitive style, depressive symptoms, and stressors, although the correlation with peer stressors was at the trend level (p = .08). Age was also negatively correlated with positive parenting. In addition, 55 youth (19 %) experienced a clinical depressive episode within the 1.5 year period of the study.

Table 1.

Means, Standard deviations, and bivariate associations among primary variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pos. parent | - | |||||||||

| 2. Neg. parent | −.18** | - | ||||||||

| 3. Peer stress | .06 | −.01 | - | |||||||

| 4. Fam stress | −.08 | −.02 | .46*** | - | ||||||

| 5. NP stress | −.08 | .01 | .62*** | .69*** | - | |||||

| 6. ACSQ | −.09 | .01 | .25*** | .33*** | .31*** | - | ||||

| 7. CDI BSL | −.09 | .00 | .42*** | .43*** | .43*** | .38*** | - | |||

| 8. CDI 6 mo | −.12* | .06 | .40*** | .33*** | .40*** | .31*** | .53*** | - | ||

| 9. CDI 18 mo | −.12 ϯ | .00 | .36*** | .39*** | .48*** | .34*** | .51*** | .51*** | - | |

| 10. Age | −.26*** | .00 | .11 | .31*** | .40*** | .25*** | .15* | .12* | .24*** | - |

| Mean | 2.54 | 1.64 | 5.62 | 5.69 | 17.01 | 2.79 | 5.43 | 4.04 | 4.84 | |

| SD | 1.27 | .88 | 4.72 | 4.18 | 11.84 | .82 | 5.06 | 4.66 | 4.75 | |

| Range | 1 – 5 | 1 – 5 | 0 – 22 | 0 – 25 | 0 – 61 | 1 – 6.27 | 0 – 29 | 0 – 37 | 0 – 20 |

Note.

p <.001

p < .01.

p < .05.

p = .05.

Pos. parent = positive parenting; Neg. parent = negative parenting; Fam = family; NP = non-peer; ACSQ Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; BSL = baseline; mo = months.

T-tests showed no significant gender differences for primary continuous variables (see Table 2). T-tests examining pubertal differences showed that post-pubertal youth encountered more stressors of all types, higher levels of negative cognitive style, and higher levels of depressive symptoms, than pre-pubertal youth. These trends are consistent with pubertal effects typically observed in the depression literature (Hankin & Abela, 2005; Hankin et al., 2015; Jacobs, Reinecke, Gollan, & Kane, 2008; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). In addition, post-pubertal youth experienced lower levels of positive parenting on average. Finally, more than twice as many girls (N=36) than boys (N=16) experienced a depressive episode during the study, and almost twice as many postpubertal youth (N =34) experienced a depressive episode compared to prepubertal youth (N = 18), which is also in line with prior research examining gender and pubertal effects on clinical depression (Hankin et al., 1998; 2015).

Table 2.

Gender and pubertal differences for primary continuous variables

| Variable | BoysMean (SD) | GirlsMean (SD) | Gender Differences (t) | Pre-pubertal Mean (SD) | Post-pubertalMean (SD) | Pubertal Differences (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive parenting | 2.52 (1.26) | 2.56 (1.28) | −.24 | 2.72 (1.22) | 2.24 (1.30) | 2.93** |

| Negative parenting | 1.69 (.93) | 1.60 (.85) | .89 | 1.62 (.86) | 1.65 (.89) | .13 |

| Peer stressors | 5.08 (4.19) | 6.01 (5.04) | −1.66 | 5.21 (4.75) | 6.35 (4.81) | −1.94 ϯ |

| Family stressors | 5.42 (3.97) | 5.89 (4.32) | −.91 | 4.79 (3.41) | 6.90 (4.79) | −4.24*** |

| Non-peer stressors | 17.06 (11.75) | 16.97 (11.94) | .06 | 13.28 (9.22) | 22.10 (13.09) | −6.47*** |

| Cognitive style | 2.84 (.81) | 2.75 (.83) | .88 | 2.64 (.86) | 2.99 (.72) | −3.45** |

| CDI baseline | 5.17 (4.59) | 5.61 (5.39) | .47 | 4.65 (4.50) | 6.66 (5.72) | −3.12** |

| CDI 6 months | 3.58 (3.59) | 4.36 (5.28) | −1.35 | 3.38 (3.72) | 5.01 (5.59) | −2.65** |

| CDI 18 months | 4.40 (4.37) | 5.15 (5.00) | −1.25 | 3.83 (4.33) | 6.44 (5.10) | −4.17*** |

Note.

p <.001

p < .01.

p = .05.

CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory.

Conditional Indirect Effect of Positive Parenting on Youth Depression and Depressive Symptoms

Peer stressors

The test of the conditional indirect effect with positive parenting (IV), clinical depression (DV) and peer stressors (moderator) showed that exposure to peer stressors moderated the association of positive parenting on clinical depression through negative cognitive style. Specifically, the bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect fell entirely below zero at high levels of peer stressors, indicating that that low levels of positive parenting was associated with a greater likelihood of a clinical depressive episode during the course of the study through a negative cognitive style for youth exposed to greater peer stressors (see Table 3). However, at low levels of peer stressors, the bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect contained zero, indicating that indirect effect was not significant for youth exposesd to low levels of peer stressors. Table 3 also shows that peer stressors moderated the indirect effect of positive parenting on youth depressive symptom severity at all timepoints examined for this study (baseline, 6-month, and 18-month follow-up), consistent with the results for clinical depression. Thus, results indicate that exposure to peer stressors moderated the indirect effect of positive parenting on concurrent youth depressive symptoms (i.e., baseline depressive sytmptoms) through negative cognitive style, and on depressive symptoms 6 months and 18 months later, after controlling for baseline symptoms. The conditional indirect effect remained significant after controlling for either gender, pubertal development, or age, for all depression related outcomes examined in this study.

Table 3.

Conditional indirect effect‡, Standard Errors, and Confidence Interval at high and low levels of stressors for all models.

| Model | Clinical Depresssion | CDI baseline | CDI 6 months | CDI 18 months | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. parent | Stress Level | Effect | SE | CI | Effect | SE | CI | Effect | SE | CI | Effect | SE | CI |

| Peer stress | High | −.08* | .04 | −.18 to −.02 | −.34* | .13 | −.62 to −.11 | −.10* | .07 | −.30 to −.01 | −.14* | .08 | −.35 to −.03 |

| Low | .00 | .03 | −.08 to .06 | .01 | .14 | −.29 to .24 | .00 | .04 | −.10 to .08 | −.01 | .06 | −.16 to .10 | |

| Non-peer stress | High | .00 | .01 | −.03 to .03 | −.02 | .13 | −.28 to .23 | −.01 | .04 | −.14 to. 05 | −.00 | .06 | −.13 to .11 |

| Low | .00 | .03 | −.04 to .07 | −.21 | .14 | −.52 to .02 | −.06 | .05 | −.23 to .00 | −.10§ | .07 | −.29 to −.00 | |

| Family stress | High | .01 | .03 | −.05 to .08 | .04 | .13 | −.21 to .30 | −.00 | .04 | −.11 to .06 | −.01 | .06 | −.15 to .10 |

| Low | −.05§ | .04 | −.15 to −.00 | −.24 | .13 | −.53 to .00 | −.06 | .05 | −.22 to .00 | −.09 | .07 | −.27 to .01 | |

| Neg. parent | Stress Level | Effect | SE | CI | Effect | SE | CI | Effect | SE | CI | Effect | SE | CI |

| Peer stress | High | .05 | .04 | −.01 to .17 | .23 | .17 | −60 to .14 | .07 | .07 | −.01 to .27 | .10 | .09 | −.02 to .34 |

| Low | .05 | .05 | −.17 to .02 | −.24 | .17 | −.29 to .24 | −.07 | .07 | −.28 to .04 | −.11 | .10 | −.35 to .05 | |

| Non-peer stress | High | −.01 | .05 | −.11 to .08 | −.05 | .18 | −.39 to .33 | −.01 | .06 | −.16 to .11 | .02 | .09 | −.15 to .24 |

| Low | .02 | .04 | −.05 to .13 | .08 | .18 | −.24 to .48 | .04 | .07 | −.06 to .24 | .03 | .09 | −.13 to .25 | |

| Family stress | High | −.01 | .05 | −.09 to .11 | −.02 | .21 | −.37 to .45 | .01 | .07 | −.12 to .19 | .03 | .11 | −.16 to .30 |

| Low | .01 | .04 | −.06 to .11 | .05 | .17 | −.27 to .40 | .07 | .13 | −.17 to .34 | .06 | .15 | −.22 to .37 | |

Note.

p < .05.

Effects are undstandardized.

Effect observed at 95% confidence level is no longer significant after controlling for age.

Pos. parent = positive parenting; Neg. parent = negative parenting.

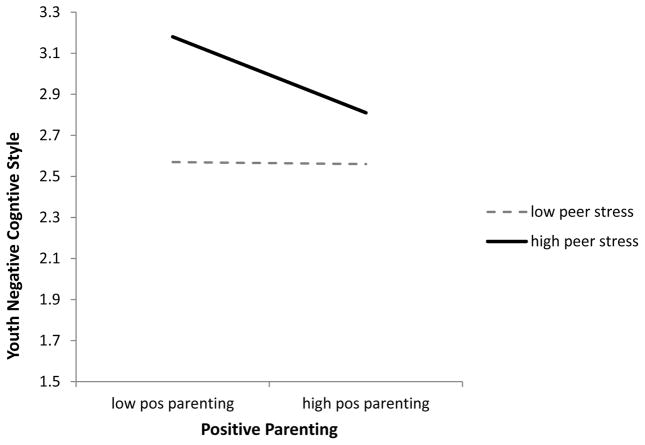

We also presented path coefficients for components of the models testing the conditional indirect effect in Tables 4a and 4b. Results showed that exposure to peer stressors significantly moderated the association between positive parenting and youth cognitive style (a3, see Table 4a). This interaction is depicted in Figure 3. Simple slope analyses in PROCESS indicated that at low levels of exposure to peer stressors (1 SD below the mean), there was no association between positive parenting and youth negative cognitive style (effect = −.00, p =.96). However, at high levels of exposure to peer stressors (1SD above the mean), there was a significant negative association between positive parenting and youth negative cognitive style (effect = −.14, p < .01), suggesting that low levels of positive parenting contribute to a negative cognitive style for youth who also experience high levels of peer stressors.

Table 4a.

Regression coefficients for a1, a2, and a3 paths predicting cognitive style (intervening variable) for conditional indirect effects models with positive parenting (IV).

| Cognitive Style | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | → | Coeff. | SE |

| Pos. parenting | a1 | −.07 | .04 |

| Peer stressors | a2 | .05*** | .01 |

| Pos. parent x peer stress | a3 | −.01* | .01 |

Note.

p <.001.

p < .05.

Table 4b.

Regression coefficients for c′ and b paths predicting depression related outcomes for conditional indirect effect models with positive parenting (IV) and peer stressors (moderator).

| Clinical Depresssion | CDI BSL | CDI 6 months | CDI 18 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | → | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE |

| Pos. parenting | c′ | −.13 | .13 | −.19 | .21 | −.22 | .21 | −.31 | .20 |

| Cognitive style | b | .52** | .19 | 2.33*** | .43 | .65* | .34 | .98** | .37 |

| CDI BSL | - | - | - | - | - | .43*** | .06 | .42*** | .06 |

Note.

p <.001

p < .01.

p< .05

Figure 3.

The interaction for positive parenting x peer stressors predicting youth negative cognitive style.

Table 4b shows the association between negative cognitive style and clinical depression, and also with depressive symptoms (path b) within the conditional indirect effects models. Negative cognitive style was associated with all outcome variables in these models. The direct effect (path c′) was not significant for any of the models.

Non-peer stressors

We conducted analyses using non-peer stressors instead of peer stressors as the moderating variable to investigate whether the conditional indirect effect held for other types of stressors. The indirect effect of positive parenting on clinical depression was not significant at low or high levels of stressors (see Table 3). Similarly, the indirect effect of positive parenting on depressive symptoms at baseline and at 6 months was not significant for both high and low stressors. However, the indirect effect on depressive symptoms was significant at 18 months for low levels of stressors, but not high levels of stressors. Path coefficients for this model showed that non-peer stressors was significantly associated with negative cognitive style (a2 = .02, p < .001), but positive parenting was not (a1 = −.05, p = .18). The interaction between non-peer stressors and positive parenting predicting negative cognitive style was not significant in this model (a3 = .00, p =.22).

The conditional effect with non-peer stressors remained significant after controlling for gender or puberty, but not age. Specifically, after controlling for age, the bootstrap confidence interval contained zero at high levels of non-peer stressors (−.11 to .09) and at low levels (−.25 to .00).

Family stressors

We separated out family stressors from other types of non-peer stressors to examine whether the conditional indirect effect observed for peer stressors would hold for other types of social stressors in particular. When predicting clinical depressive episodes, the indirect effect of positive parenting through negative cognitive style was observed for low levels of family stressors, but not high levels of family stressors (See table 3). Path coefficients for this model showed that family stressors was significantly associated with negative cognitive style (a2 = .07, p < .001), but positive parenting was not (a1 = −.04, p = .25). Moreover, the interaction between family stressors and positive parenting predicting negative cognitive style was not significant in this model (a3 = .01, p =.13). Again, the conditional indirect effect remained significant after controlling for gender or puberty, but not age. The bootstrap confidence interval contained zero at high levels of family stressors (−.03 to .08) and at low levels (−.13 to .00), when including age as a covariate.

When predicting severity of depressive symptoms, the conditional indirect effect was not significant at all timepoints (baseline, 6 months, and 18 months, see Table 3). In other words, positive parenting was not associated with depressive symptoms through negative cognitive style at either high or low levels of family stressors.

Conditional Indirect Effect of Negative Parenting on Youth Clinical Depression and Depressive Symptoms

We also tested whether peer stressors moderated the indirect effect of negative parenting on youth clinical depression and depressive symptoms through youth negative cognitive style. As can be seen in Table 3, bootstrap confidence intervals for the indirect effect contained zero for low levels of peer stressors and high levels of peer stressors in all models. These results indicate that the indirect effects across levels of peer stressors was nonsignficant for all depression related outcomes examined. The conditional indirect effect of negative parenting on all depression and depressive symptoms was also not significant when non-peer and family stressors were examined as moderators in all models.

New Episodes of Depression

We were interested to know whether our model predicted new episodes of clinical depression for youth. For these analyses, youth were classified into the depressed group only if they experienced a depressive episode during the course of study and had no past history of depression. Twenty-nine youth (approximately 10% of the sample) experienced a new onset of depression during the 18 month study. However, none of our models significantly predicted new onsets of depression, perhaps because of the low base rate of new episodes.

Discussion

Prior research on the associations between parenting, cognitive vulnerability, and depression has been limited by an over reliance on questionnaire methods, a lack of attention to parenting in specific contexts, and a general neglect of the potential moderating role of stressors. Additionally, very little is known about developmental processes through which parenting might contribute to clinical levels of depression, across the transition into adolescence. Findings from the current study supported a developmental model in which low levels of positive parenting during a youth stressor task were indirectly associated with clinical depressive episodes and severity of depressive symptoms, through the influence of youth negative cognitive style, but only for youth who also experienced a high number of peer stressors. Of note, findings showed that among youth exposed to high levels of peer stressors, positive parenting was indirectly associated with concurrent depressive symptoms, as well as longitudinal increases in depressive symptoms 6 month and 18 months later, through negative cognitive style. Thus, these findings elucidate potential conditions under which exposure to problematic parenting is associated with worsening depressive symptoms over time and the onset of clinical depressive episodes. The main findings were obtained among youth before and throughout the adolescent transition, suggesting the continued importance of parenting across a developmental period characterized by a change in parent-child relationships and a marked rise in peer stress.

Specifically, findings suggest that youth who do not receive adequate levels of positive parenting from their parents in stressful contexts, such as praise and affection, are more at risk for making negative inferences about the meaning and significance of negative events, particularly in the face of a high number of peer stressors. We speculate that inadequate positive parenting from parents, which fails to communicate support and approval for youth characteristics and abilities during stressful experiences, may promote negative interpretations about the significance of stressors. Thus, youth who do not receive sufficient positive parenting from parents during times of stress may have difficulty developing adaptive beliefs about stressors, and instead develop negatively biased appraisals. If these youth are also repeatedly exposed to a high number of stressors, they may begin to form more fixed negative cognitions which contribute to negative interpretations about the role of self, causes, and consequences when negative experiences occur. Findings further suggest that the development of a negative cognitive style in turn increases risk for the worsening of depressive symptoms and increases risk for the onset of a clinical depressive episode among these youth.

Our findings are consistent with the inferential feedback hypothesis, which posits that parenting behaviors that explicitly or implicitly conveys negative information about stressors contributes to cognitive vulnerability for depression (Alloy et al., 2001; Crossfield et al., 2002). Findings also suggest the importance of observing parenting behaviors during stress-inducing contexts for youth. If parenting behaviors that convey information about stressors are particularly influential in the formation of cognitive vulnerability, assessments that can capture parenting behaviors during stressful experiences for youth may have more utility in advancing research on the relation between parenting and youth negative cognitive style. Furthermore, results are in line with prior research by suggesting that it is likely the combination of receiving inadequate parenting, and experiencing a large number of stressors, especially peer stressors, that contributes to cognitive vulnerability and/or risk for depression (Hazel et al., 2014; Mezulis et al., 2006).

Results are also consistent with theoretical models of depression that posit that exposure to problematic parenting contributes to depression during adolescence (Garber & Flynn, 2001; Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004). However, few prior studies have investigated developmental processes through which parenting might be associated with onsets of clinical depression over time across the adolescent transitional period. Moreover, this is the first study to explicitly investigate how observed parent caregiving behaviors during a youth laboratory stressor might be associated with the development of youth depression. Our findings provide support for the idea that deficient positive parenting in response to youth exposure to stressors may initiate developmental pathways contributing to depression. Exposure to other environmental factors, such as peer stressors, may then strengthen and maintain these pathways by interacting with parenting to contribute to negatively biased cognitions about stressors, which in turn contribute to clinical depression. However, given that this was a partially prospective study, caution is needed when interpreting the direction of effects. More longitudinal research is needed to better test these potential developmental pathways to depression.

Although findings suggested that inadequate parenting in the face of stress, in combination with high numbers of peer stressors, is indirectly associated with youth depression, a statistically significant main effect of parenting on clinical depression was not observed in this study. Parenting was also not concurrently or longitudinally associated with depressive symptoms, after controlling for baseline symptoms. Although previous studies have found significant correlations between parenting and depressive symptoms (Alloy et al., 2006; McLeod, Weisz, et al., 2007; Schwartz et al., 2012; Sheeber, Hops, Alpert, Davis, & Andrews 1997), as well as clinical depression (e.g., Dietz et al., 2008; Sheeber, Allen, Davis, & Sorensen, 2000; Sheeber & Sorensen, 1998), there may be several methodological reasons why this study did not show a significant effect of parenting on youth depression and depressive symptoms. First, the majority of studies that find associations between parenting factors and clinical levels of depression have used case-control or group-comparison designs, in which a group of currently depressed youth is compared to non-depressed controls on measures of parenting at a single time point (McLeod, Weisz, et al.). Thus, less is known about the extent to which parenting is prospectively associated with clinically significant depression over a period of time in a community sample of youth. Second, a large majority of prior studies have use self-report measures of parenting, which have been shown to yield larger effects compared to observational assessments, perhaps due to negative biases associated with depression, on top of inflated correlations due to mono-method designs (McLeod, Weisz, et al.). Therefore, the use of multiple methods, including an observational approach to assess parenting and diagnostic interviewing to assess clinical depression, in the current study reduced the mono-method bias and may have made it more difficult to find a statistically significant association between parenting and youth depression. As such, our approach with non-redundant methods may have contributed to a less biased, and more accurate estimation of this effect. However, Schwartz and colleagues (2011; 2012) found that observed maternal parenting behaviors was associated with the onset of clinical depressive episodes and increases in depressive symptoms over 2–3 years among a community sample of youth. A significant effect of parenting on depression related outcomes may be more likely to be observed over a longer follow-up period, because there is greater opportunity to capture onsets of depressive episodes and worsening of depressive symptoms among adolescents.

Given the growing significance of peer relationships across the transition into adolescence, and recent evidence suggesting that peer stressors may more strongly and consistently interact with aspects of parent-child relationships to predict cognitive vulnerability (Mezulis et al., 2006), emotional reactivity (Oppenheimer et al., in press), and depressive symptoms (Hazel et al., 2014) among youth, we examined the moderating role of peer stressors in particular. Peer stressors consistently moderated the indirect effect of positive parenting on depression related outcomes in all models examined, such that positive parenting was indirectly associated with depression and depressive symptoms at high levels of peer stressors, but not low levels. These findings provide additional evidence that peer stressors more robustly interact with parenting to predict vulnerability for depression compared to non-peer stressors. Developmental theory posits that parenting, particularly parenting in the face of high levels of youth stress, contributes to youth cognitions about their social environment in particular (Bowlby, 1977; Calkins, 1994). Thus, problematic parenting may be more likely to influence how youth interpret other negative experiences within certain social environments (i.e peer stressors), and thus may be more likely to affect how peer stressors contribute to stable cognitive biases. It is also important to take into consideration that parenting was purposefully measured during a socially relevant stressor task in this study, and it is possible that parenting measured in this particular context has an especially strong influence on how peer stressors relate to youth negative attributional style.

We also examined the moderating effect of non-peer stressors to compare with findings involving peer stressors, consistent with prior work (Hazel et al., 2014). In addition, to further investigate the extent to which findings were specific to peer stressors versus other types of social stressors, we separated out family stressors from our assessment of non-peer stressors to examine their specific role as moderators of the indirect effect models in this study. Unlike peer stressors, non-peer stressors and family stressors did not consistently moderate the indirect effect of parenting across models; a significant moderation effect was observed in only one of the four models for each of these variables. In addition, the significant indirect effect of positive parenting on depression related outcomes was observed for low levels of non-peer and family stressors, which is different than the moderation effect observed for peer stressors. However, this moderating effect did not hold after controlling for age. Overall, there was weak evidence supporting a conditional indirect effect for other types of non-peer stressors, including family stressors. These results are in line with the study by Mezulis and colleagues (2006) which also showed that peer stressors interacted with parenting to predict negative cognitive style more consistently than other types of stressors. It is unclear why posititve parenting may interact with peer, but not family stressors, given that these are both types of social stressors. We speculate that youth may be exposed to negative messages about the causes of negative events from family members and parents when exposed to high levels of family stressors, such as parent-child and parent-parent conflict (Stark, Schmidt, & Joiner, 1996), and so positive parenting might have less influence on cognitive vulnerability when youth are also faced with these types of family experiences. More research is needed to understand the interplay between parenting and parent/family related stressors on cognitive vulnerability and risk for depression among youth.

Negative parenting did not interact with peer stressors to predict depression or depressive symptoms through negative cognitive style in any of the models. Prior research has also found that positive parenting, but not negative parenting, interacts with peer stressors to influence youth risk for mood reactivity (Oppenheimer et al. 2016), although other research has found more support for negative parenting predicting cognitive vulnerability, in interaction with peer negative events (Mezulis et al., 2006). On average, low levels of negative parenting were observed during the stressor task, perhaps due to the community sample of youth used for the study. In addition, the nature of the youth laboratory stressor task likely elicited higher levels of support and positive parenting, but lower levels of negative parenting, compared to other parent-child observational tasks (e.g., conflict discussion task). However, it is possible that more extreme levels of negative parenting may be associated with cognitive vulnerability and risk for depression. It will be important for future research to continue to examine the role of negative parenting in the development of cognitive vulnerability and depression, particularly in combination with youth stressors.

Finally, none of our models predicted new onsets of depressive episodes. However, there was a low base rate of new depressive episodes, which is to be expected given that we used a community sample that included pre-pubertal youth. Analyses examining depressive symptoms provide support for the longitudinal prediction of increases in depressive symptoms, which suggests that parenting may interact with stressors to contribute to the development of new episodes of clinical depression. However, larger samples of youth during the critical pubertal transition may be needed to adequately capture first depressive episodes.

Strengths, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

Several aspects of this study provide for a more rigorous and innovative test of primary hypotheses, which helps to enhance confidence in findings and inform understanding of etiological processes in the development of adolescent depression. This study used observational methods to carefully assess aspects of parenting behavior during a laboratory stressor, which addresses limitations of prior mono-method, questionnaire studies that assess parenting in nonspecific contexts. Furthermore, this study is one of the first to measure positive caregiving in response to youth during a stress-inducing context among children transitioning into and across adolescence. We were also able to prospectively assess for onsets of clinical depression over time and increases in depressive symptoms by using repeated diagnostic clinical interviews and measures of depressive symptoms. Finally, we tested a more comprehensive model of how interplay among parenting and stressors may work together to predict depression and depressive symptoms from middle childhood into adolescence.

Despite several strengths of this study, future research is needed to address limitations. As mentioned previously, this was a partially prospective study, but multiple constructs were still assessed at one time point, which limits interpretations about temporal ordering of risk factors. We theorized that parenting and peer stressors likely precede cognitive vulnerability, but it is possible that negatively biased interpretations of interpersonal interactions and stressors leads to problems in relationships with parents and peers, in line with stress generation and interpersonal theories of depression (Joiner & Coyne, 1999, Rudolph, Flynn, & Abaied, 2008). It is also probable that there are transactional, rather than uni-directional associations, between environmental factors and youth characteristics that contribute to risk for depression (Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, 1984; Rudolph et al., 2008). Therefore, future research is needed to disentangle potential longitudinal, transactional associations among primary variables. Future research may also benefit from making further distinctions among categories of stressors. Although we differentiated peer stressors from family and other types of stressors, it is unclear whether effects are the same for achievement stressors versus health stressors, versus other kinds of non-peer stressors. It is also important to note that we only examined parenting in one very specific context in this study. It should be the goal of future research to begin to compare the effects of parenting across different contexts, to try to better understand what parenting behaviors, during what types of parent-child interactions, have the greatest effect on youth psychopathology. Finally, the sample included only youth from the community who self-selected into the study (i.e., responded to the study letters), and so it is unclear the extent to which the findings generalize to the larger community. Replications of this study in other community samples of youth are needed to provide more support for study findings and conclusions.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The majority of existing parenting interventions are designed to target externalizing symptoms in children and adolescents, and focus on contingencies of reinforcement (e.g., parent management training), increasing parent monitoring, and problem solving (Burke, Brennan, & Roney, 2010). In comparison, parent involvement is markedly absent from most intervention programs targeting youth depression. Findings from this study suggest that parenting strategies aimed at increasing positive and supportive parenting to youth during periods of stress may be effective for the prevention and/or treatment of clinical depression, particularly among youth most at risk for experiencing a high number of peer stressors during the transition into adolescence. Findings are also in line with several recent studies testing promising new parenting interventions for youth depression and internalizing symptoms that target specific parenting behaviors as a way to improve youth coping (Compas et al., 2009), emotion regulation (Kehoe, Havighurst, & Harley, 2014), and interpersonal functioning with peers (Dietz, Weinberg, Brent, & Mufson, 2015). Thus, latest research indicates that 1) increasing parent involvement may be important for enhancing future depression interventions, and 2) there may be a need for a shift of focus from typical parenting interventions designed for externalizing disorders, to new, innovative programs for depression that emphasize parenting behaviors that can aid youth in developing adaptive and effective responses to stressors, especially peer stressors, across the transition into adolescence.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

Author Note

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH077195). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. NY: Guilford; 2008. pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Stolow D, Mineka S, Yao S, Zhu XZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depressive symptoms in adolescents in urban and rural Hunan, China: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:765–778. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.517159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological review. 1989;96:358–372. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy L, Abramson LY, Smith JM, Gibb BE, Neeren AM. Role of parenting and maltreatment histories in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: Mediation of cognitive vulnerability to depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:3–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy L, Abramson LY, Tashman NA, Berrebbi DS, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, … Morocco A. Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Parenting, cognitive, and inferential feedback styles of the parents of individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:397–423. doi: 10.1023/A:1005534503148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Worthman C, Costello EJ. Puberty and depression. In: Hayward C, editor. Gender differences at puberty. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He J, Burstein M, Merikangas KR. Major depression in the national comorbidity survey – adolescent supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: Int. Univ Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. I. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. An expanded version of the Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture, delivered before the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 19 November 1976. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1977;130:201–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.130.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child development. 1987;58:1101–1113. doi: 10.2307/1130550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke K, Brennan L, Roney S. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of the ABCD Parenting Young Adolescents Program: Rationale and methodology. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2010;22:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:53–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Orue I, Hankin BL. Transactional relationships among cognitive vulnerabilities, stressors, and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;41:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9691-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi TC, Hinshaw SP. Mother-child relationships of children with ADHD: The role of maternal depressive symptoms and depression-related distortions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:387–400. doi: 10.1023/a:1015770025043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Schneider–Rosen K. Toward a transactional model of childhood depression. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1984;26:5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE, Martin JM, Peeke LG, Seroczynski AD, Tram JM, … Maschman T. The development of multiple domains of child and adolescent self-concept: A cohort sequential longitudinal design. Child Development. 2001;72:1723–1746. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Keller G, Champion JE, Rakow A, Reeslund KL, … Cole DA. Randomized controlled trial of a family cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for children of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1007–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona R, Lefkowitz ES, Sigman M, Romo LF. Latino adolescents’ adjustment, maternal depressive symptoms, and the mother-adolescent relationship. Family Relations. 2005;54:386–399. [Google Scholar]

- Cox SJ, Mezulis AH, Hyde JS. The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in depressive rumination in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:842–852. doi: 10.1037/a0019813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossfield AG, Alloy LB, Gibb BE, Abramson LY. The development of depressogenic cognitive styles: The role of childhood negative life events and parental inferential feedback. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;16:487–502. doi: 10.1891/jcop.16.4.487.52530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Grusec JE. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:44–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz LJ, Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Silk JS, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, … Ryan ND. Mother-child interactions in depressed children and children at high risk and low risk for future depression. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:574–582. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz LJ, Weinberg RJ, Brent DA, Mufson L. Family-based interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed preadolescents: Examining efficacy and potential treatment mechanisms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science. 2009;10:87–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M. The role of shame and attributional style in children’s’ and adolescents’ adaptation to sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Flynn C. Predictors of depressive cognitions in young adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:353–376. doi: 10.1023/A:1005530402239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RDD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental psychology. 1994;30:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN. In search of explanations for early pubertal timing effects on developmental psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:513–524. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D. The longitudinal effects of stressful life events on adolescent depression are buffered by parent-child closeness. Development and psychopathology. 2009;21:621–635. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Abela JRZ. Emotional abuse, verbal victimization, and the development of children’s’ inferential styles, and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:161–176. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9106-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:264–274. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Rose DT, Whitehouse WG, Donovan P, … Tierney S. History of childhood maltreatment, negative cognitive styles, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:425–446. doi: 10.1023/A:1005586519986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Vance A, Gomez A. Children’s Depression Inventory: Invariance across children and adolescents with and without depressive disorders. Psychological assessment. 2012;24:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0024966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: differences in psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:90–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Stress and the development of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression explain sex differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3:702–714. doi: 10.1177/2167702614545479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: Prospective tests of attachment, cognitive vulnerability, and stress as mediating processes. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:645–671. doi: 10.1007/s10608-005-9631-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: A short-term prospective multiwave study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:324–333. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]