Abstract

Possession of the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE) is the major genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD). Although numerous hypotheses have been proposed, the precise cause of this increased AD risk is not yet known. In order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of APOE4's role in AD, we performed RNA-sequencing on an AD-vulnerable vs. an AD-resistant brain region from aged APOE targeted replacement mice. This transcriptomics analysis revealed a significant enrichment of genes involved in endosomal–lysosomal processing, suggesting an APOE4-specific endosomal–lysosomal pathway dysregulation in the brains of APOE4 mice. Further analysis revealed clear differences in the morphology of endosomal–lysosomal compartments, including an age-dependent increase in the number and size of early endosomes in APOE4 mice. These findings directly link the APOE4 genotype to endosomal–lysosomal dysregulation in an in vivo, AD pathology-free setting, which may play a causative role in the increased incidence of AD among APOE4 carriers.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein E, APOE, APOE4, endosome, lysosome, Alzheimer's disease, transcriptomics, RNA-seq

Introduction

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) plays a vital role in the transport of cholesterol and other lipids through the bloodstream, as well as within the brain (Mahley and Rall, 2000; Han, 2004; Holtzman et al., 2012). In addition, possession of the ε4 allele of APOE is the primary genetic risk factor for developing late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD). While APOE4's role in AD has often been attributed to its ability to increase the aggregation and decrease the clearance of Aβ (Rebeck et al., 1993; Schmechel et al., 1993; Ma et al., 1994; Castano et al., 1995; Bales et al., 1997; Holtzman et al., 2000; Castellano et al., 2011), APOE4 expression has also been shown to affect a wide array of Aβ-independent processes in the brain [see reviews by Huang (2010) and Wolf et al. (2013)], including a potential role in increasing the pathogenicity of other proteins, such as tau and α-synuclein (see review by Huynh et al., 2017).

Given these observations, it is important to elucidate the full range of effects that APOE4 expression has on the brain in order to identify new mechanisms that might be responsible for the increased AD risk among APOE4 carriers. To that end, we have performed RNA-sequencing on the entorhinal cortex (EC) and the primary visual cortex (PVC) from 14 to 15 month old APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 targeted replacement mice. APOE targeted replacement mice express human APOE in place of the mouse Apoe gene and are devoid of overt AD pathology (Sullivan et al., 1997, 2004). Since the majority of APOE4 carriers possess only one ε4 allele (~22.2 vs. ~1.9% with two alleles, according to AlzGene), we chose to limit our initial comparison to mice expressing APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3. The EC was utilized as an AD-vulnerable brain region because it is one of the first brain regions to develop AD pathology (Braak and Braak, 1991; Bobinski et al., 1999), and it has been shown to be particularly vulnerable to APOE4-linked morphological changes (Shaw et al., 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2013; DiBattista et al., 2014). The PVC was utilized as an AD-resistant brain region because it is relatively spared in AD (Braak and Braak, 1991; Minoshima et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2010) and it has not been reported to demonstrate any APOE4-linked morphological changes.

Our transcriptomics analysis identified over 1,000 genes that were differentially affected by APOE4 gene expression in the EC. Endosomal–lysosomal pathway genes were significantly enriched among these genes. To confirm the biological importance of these gene expression differences, we examined brain sections by immunohistochemistry from APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice, which revealed morphological differences in endosomal–lysosomal compartments in the APOE4/4 mice, including an age-dependent increase in the number and size of early endosomes in the brains of these mice. Together, these findings implicate APOE4 in the dysregulation of the endosomal–lysosomal pathway in the brain, which may be a contributing factor to the development of AD among APOE4 carriers.

Materials and methods

Mice

All experimental procedures involving animals in this study were approved by and complied with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Nathan Kline Institute and Columbia University Medical Center. Human APOE targeted replacement mice were originally developed by Sullivan et al. (1997, 2004). These targeted-replacement mice express human APOE under the control of the endogenous murine promoter, which allows for the expression of human APOE at physiologically regulated levels in the same temporal and spatial pattern as endogenous murine Apoe. For our initial transcriptomics analysis, 14–15 month old male APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice were used, whereas immunohistochemical analysis of endosomal and lysosomal morphology was performed on approximately equal numbers of male and female APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice at 6, 12, 18, and 25 months of age. Mice were derived from two separate colonies. The APOE genotype of the mice was confirmed either in-house by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis following polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as previously described (Hixson and Vernier, 1990) or using a PCR-based method developed by Transnetyx (Cordova, TN).

RNA extraction for transcriptomics analysis

Mouse numbers were selected to be similar to those used in previous experiments (Hauser et al., 2014; Dillman et al., 2016). Male mice expressing human APOE3/3 (10 mice) or APOE3/4 (19 mice) were aged to 14–15 months, at which point they were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and brain tissues containing the EC and PVC were dissected and snap frozen on dry-ice. Brain tissues were stored in RNase-free eppendorf tubes at −80°C prior to extraction. Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues by homogenizing each tissue sample using a battery-operated pestle mixer (Argos Technologies, Vernon Hills, IL) in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). RNA concentration was measured using a nanodrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and RNA integrity (RIN) was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). All RNA samples possessed a RIN of 8 or higher. RNA was stored at −80°C prior to use.

RNA-sequencing and analysis

Starting with 2 μg of total RNA per sample, Poly(A)+ mRNA was purified, fragmented and then converted into cDNA using the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit v2 (Illumina cat# RS-122-2001) as per the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA). For RNA-Sequencing of the cDNA, we hybridized 5 pM of each library to a flow cell, with a single lane for each sample, and we used an Illumina cluster station for cluster generation. We then generated 149 bp single end sequences using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer. For analysis, we used the standard Illumina pipeline with default options to analyze the images and extract base calls in order to generate fastq files. We then aligned the fastq files to the mm9 mouse reference genome using Tophat (v2.0.6) and Bowtie (v2.0.2.0). In order to annotate and quantify the reads to specific genes, we used the Python module HT-SEQ with a modified NCBIM37.61 (containing only protein coding genes) gtf to provide reference boundaries. We used the R/Bioconductor package DESeq2 (v1.10.1) for comparison of aligned reads across the samples. We conducted a variance stabilizing transformation on the aligned and aggregated counts, and then the Poisson distributions of normalized counts for each transcript were compared across APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 groups using a negative binomial test. We corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure and selected all genes that possessed a corrected p-value of less than 0.05. Finally, a heat map based on sample distance and a volcano plot based on fold change and adjusted p-values were generated using the R/Bioconductor package ggplot2 (v2.0.0).

Pathway analysis

Enriched KEGG pathways were identified using the ClueGo application (version 2.1.7) in Cytoscape (version 3.2.1). Briefly, all differentially expressed EC genes from the RNA-Seq analysis were entered into the application and searched for significantly enriched KEGG pathways possessing a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value of less than 0.05. For gene ontology (GO) pathway analysis, differentially expressed EC genes were entered into NIH's DAVID program (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/; version 6.8), and a functional annotation chart was generated for all significantly enriched GO Biological Process Terms, GO Cellular Component Terms and GO Molecular Function Terms possessing a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value of less than 0.05.

Immunolabeling of fixed brain tissue

For immunolabeling of brain tissue, mice were transcardially perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Brains were removed and post-fixed for 3 days in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C, and subsequently cut into 40 μm-thick coronal sections using a vibratome, as we have described previously (Choi et al., 2013). Free-floating sections were labeled with anti-Rab5a (sc-309; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; dilution 1: 100) or an in-house anti-CatD rabbit polyclonal antibody (Yang et al., 2014). Tissue sections were also co-labeled with a Nissl stain to determine the border of the cell soma. Following binding of appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY; dilution 1:500), immunofluorescence was captured at 100 × magnification using an Axiovert 200M Fluorescence Imaging Microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) by a genotype-blinded observer. Quantification and morphometric analysis of labeled particles per cell was measured using ImageJ's automated particle analysis (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland) after thresholding the density of Rab5a or CatD-positive signal over background, as we have done previously (Choi et al., 2013). With this method, we obtained automated calculations of average area, particle count, and area fraction within a manually drawn border around the cell soma. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test between groups. Cell and mouse numbers were selected to be similar to those used in previous experiments (Choi et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2016). For the quantifications in EC, we used n = 118 neurons from 7 mice (APOE3/3) and n = 85 neurons from 6 mice (APOE4/4) for Rab5a, and n = 126 neurons from 7 mice (APOE3/3) and n = 139 neurons from 7 mice (APOE4/4) for CatD. For the quantifications in cingulate cortex, we used n = 48 neurons (APOE3/3) and 52 neurons (APOE4/4) from 4 mice per genotype at age 6 months, n = 115 neurons (APOE3/3) and 88 neurons (APOE4/4) from 8 mice per genotype at age 12 months, n = 267 neurons (APOE3/3) and 286 neurons (APOE4/4) from 8 mice per genotype at age 18 months, and n = 342 neurons (APOE3/3) and 141 neurons (APOE4/4) from 8 mice per genotype at age 25 months.

Data availability

The transcriptomics datasets generated during the current study are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, accession # GSE102334.

Results

Altered gene expression is observed in the EC and PVC of aged APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice

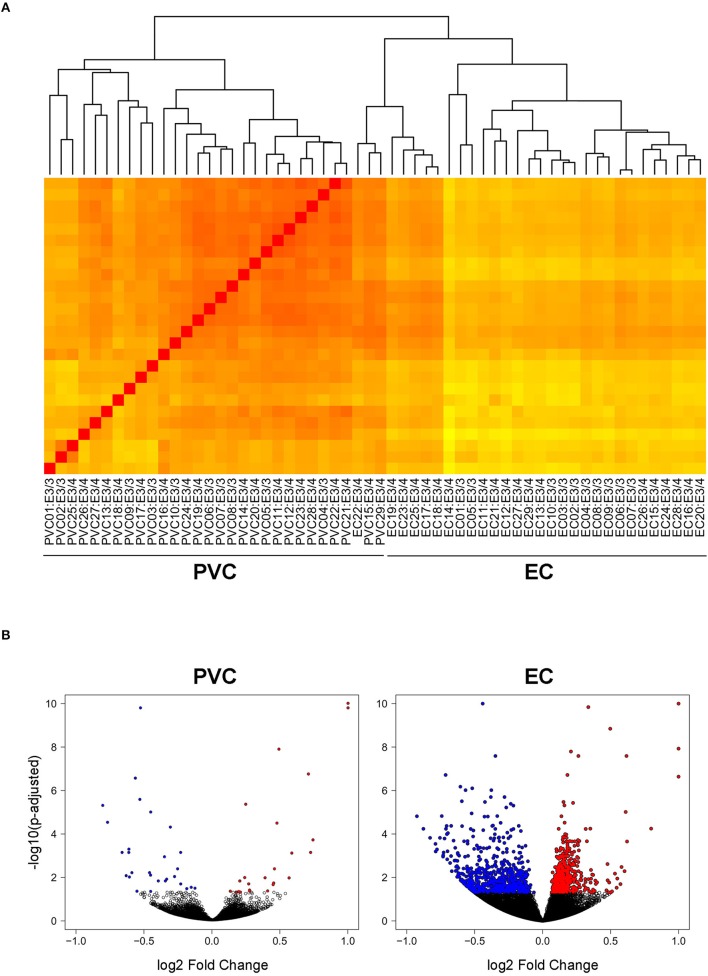

In order to investigate the effect of APOE4 expression in an AD-vulnerable vs. an AD-resistant brain region, RNA-sequencing was performed on RNA extracted from the EC and PVC of 14–15 month-old APOE targeted replacement mice expressing human APOE3/4 (19 males) vs. APOE3/3 (10 males). As shown in Figure 1A, the samples clustered independently based on brain region, but not based on genotype. This is likely due to the relatively small number of genes that were differentially expressed between APOE3/4 and APOE3/3 mice in each region versus the total number of genes analyzed. Using an FDR-corrected p-value of less than 0.05, we identified 1292 genes in the EC and 55 genes in the PVC that were differentially expressed between APOE3/4 and APOE3/3 (Tables S1, S2), out of a total of 31,246 genes analyzed. In the EC, 683 genes were decreased and 609 genes were increased in APOE3/4 mice as compared to APOE3/3 mice, while in the PVC, 28 genes were decreased and 27 genes were increased in APOE3/4 mice as compared to APOE3/3 mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Transcriptomics analysis was performed on RNA extracted from the EC and PVC of aged APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice. RNA-sequencing was performed to analyze the effects of differential APOE isoform expression on RNA levels in the PVC and EC of aged APOE mice APOE3/4 (19 APOE3/4 males vs. 10 APOE3/3 males). (A) A heat map visualizing the Euclidean distance between samples, with darker red colors indicating increased similarity. (B) Volcano plots visualizing the fold change and adjusted p-values of each gene that was differentially expressed in the PVC and EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

Genes related to endosomal–lysosomal system function are upregulated in the EC of aged APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice

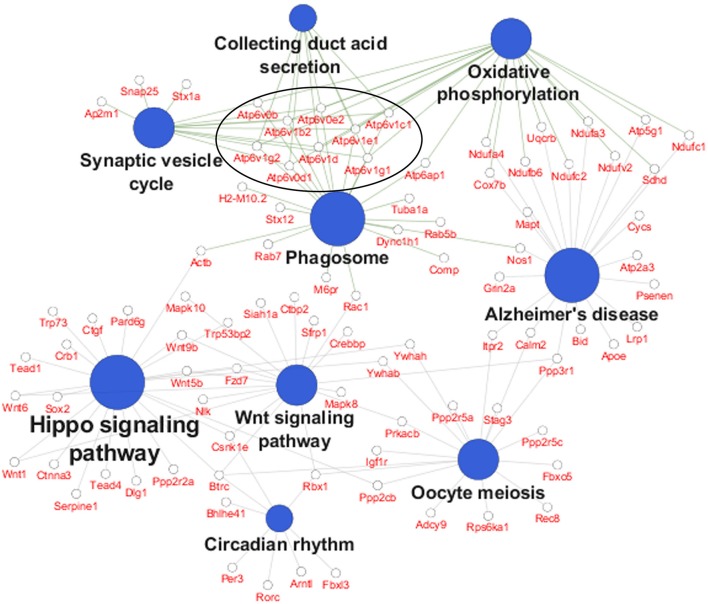

In order to identify specific cellular pathways that are affected by differential APOE isoform expression in the EC, we performed KEGG pathway analysis on the differentially expressed genes from the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice using Cytoscape's ClueGo application. This analysis identified 9 KEGG pathways that were enriched with genes from the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice (Figure 2 and Table 1). An informal analysis of these results revealed that there were four major pathway groups affected by the APOE3/4 genotype in the EC: vesicle function (synaptic vesicle cycle, collecting duct acid secretion and phagosome pathways), developmental genes (Hippo and Wnt signaling pathways), oxidative phosphorylation (oxidative phosphorylation pathway) and AD (Alzheimer's disease pathway).

Figure 2.

Pathway analysis reveals numerous pathways affected by differential APOE isoform expression. A pathway analysis was performed on the differentially expressed EC genes using Cytoscape's ClueGo application. Shown here are the significantly enriched KEGG pathways observed in the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice, with the 9 differentially expressed V-type ATPase genes circled. (Further details can be found in Table 1).

Table 1.

Enriched KEGG Pathways in the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

| Gene ontology term | KEGG ID | Number of genes | Percent matched | p-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippo signaling pathway | 4390 | 23 | 14.7 | 2.64E-05 | 0.004 |

| Synaptic vesicle cycle | 4721 | 12 | 19.4 | 1.77E-04 | 0.006 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 190 | 20 | 14.2 | 1.52E-04 | 0.007 |

| Collecting duct acid secretion | 4966 | 8 | 29.6 | 9.52E-05 | 0.007 |

| Circadian rhythm | 4710 | 8 | 25.8 | 2.76E-04 | 0.008 |

| Oocyte meiosis | 4114 | 17 | 14.7 | 3.18E-04 | 0.008 |

| Alzheimer's disease | 5010 | 22 | 12.3 | 0.001 | 0.017 |

| Phagosome | 4145 | 21 | 12.1 | 0.001 | 0.024 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 4310 | 18 | 12.6 | 0.002 | 0.025 |

Shown are all KEGG pathways enriched in the APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 EC that possessed a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05, with additional information on the number of genes that were found in each pathway and the percentage of the total genes that were matched for each pathway.

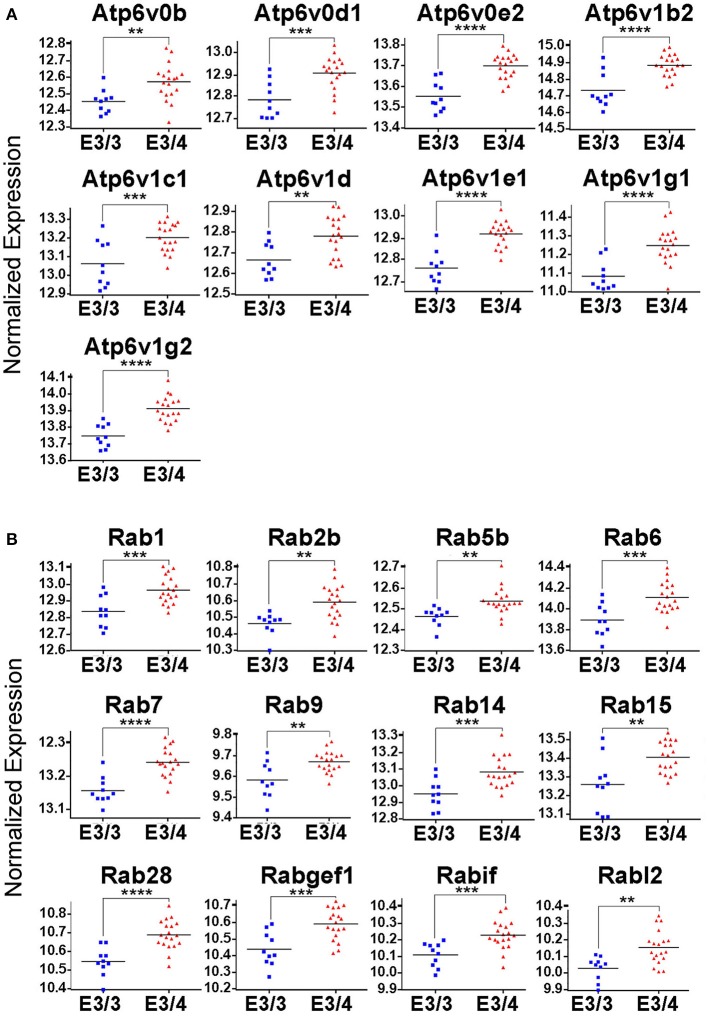

While all of these KEGG pathway groups are intriguing, we focused on the vesicle function group. As highlighted in Figure 2, an important contributor to the difference in the vesicle function group was an increase in the expression of 9 Vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-ATPases) in the EC of APOE3/4 mice (Figure 3A). V-ATPases are vital for the acidification and function of a wide range of vesicular compartments, including phagosomes in macrophages and microglia, synaptic vesicles in neurons, and endosomes, lysosomes and autophagosomes in numerous cell types (Marshansky et al., 2014; Cotter et al., 2015). In order to further explore this pathway enrichment, we also performed a DAVID analysis for Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC) and Molecular Function (MF) Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Table 2), and we found that differentially expressed EC genes were enriched in “endosome,” “lysosomal membrane” and “extracellular exosome” GO terms, in addition to numerous other vesicle and transport-related GO terms. For this reason, we chose to direct our attention to the effect of differential APOE isoform expression on the endosomal–lysosomal system.

Figure 3.

Genes related to endosomal–lysosomal system function are upregulated in the EC of APOE3/4 mice. Our RNA-Seq analysis of EC genes from aged APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice revealed an enrichment of upregulated genes related to endosomal–lysosomal system function. (A) Differentially regulated V-type ATPases in the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice. (B) Differentially regulated Rab GTPases in the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice. (**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Enriched Gene Ontology Terms in the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

| Gene ontology term | Gene ontology database | Number of genes | Percent matched | p-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein binding | GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | 315 | 28.2 | 2E-16 | 2.4E-13 |

| Cytoplasm | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 430 | 38.5 | 1.8E-12 | 1.1E-09 |

| Cytosol | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 150 | 13.4 | 6.6E-11 | 2.1E-08 |

| Membrane | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 439 | 39.3 | 1.7E-10 | 3.6E-08 |

| Extracellular exosome | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 198 | 17.7 | 1.9E-09 | 3E-07 |

| Mitochondrion | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 134 | 12 | 9.5E-08 | 0.000012 |

| Cytoplasmic vesicle membrane | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 22 | 2 | 3.8E-07 | 0.00004 |

| Cell junction | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 67 | 6 | 0.0000008 | 0.000071 |

| Myelin sheath | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 27 | 2.4 | 0.0000029 | 0.00022 |

| Transport | GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | 141 | 12.6 | 0.0000003 | 0.0011 |

| Focal adhesion | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 40 | 3.6 | 0.000024 | 0.0017 |

| Axon | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 38 | 3.4 | 0.000037 | 0.0021 |

| Lysosomal membrane | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 28 | 2.5 | 0.000036 | 0.0023 |

| Neuron projection | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 40 | 3.6 | 0.00012 | 0.0052 |

| Golgi membrane | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 39 | 3.5 | 0.0001 | 0.0053 |

| SNARE complex | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 11 | 1 | 0.00011 | 0.0055 |

| Endosome | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 48 | 4.3 | 0.00014 | 0.0058 |

| Cytoskeleton | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 82 | 7.3 | 0.00027 | 0.01 |

| Nucleoplasm | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 129 | 11.6 | 0.00032 | 0.012 |

| Perinuclear region of cytoplasm | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 56 | 5 | 0.00034 | 0.012 |

| Cell surface | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 51 | 4.6 | 0.00061 | 0.02 |

| Vesicle | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 19 | 1.7 | 0.0012 | 0.038 |

| Melanosome | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 14 | 1.3 | 0.0014 | 0.038 |

| Synaptic vesicle | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 16 | 1.4 | 0.0014 | 0.04 |

| Rhythmic process | GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | 20 | 1.8 | 0.000025 | 0.043 |

| Postsynaptic density | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 24 | 2.2 | 0.0017 | 0.044 |

| Centrosome | GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | 37 | 3.3 | 0.0017 | 0.046 |

All GO terms enriched in the APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 EC that possessed a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05, with additional information on the GO database they were found in, the number of genes that were found from each GO term and the percent of genes that were matched for each GO term (GO terms directly related to the endosomal–lysosomal system are in bold).

In addition to the increased expression of V-ATPases, further mining of the RNA-Seq data revealed 12 different Rab GTPases and associated genes (Figure 3B), including Rab5b and Rab7, which are vital for the formation and function of early and late endosomes, respectively, as well as several other important regulators of endosomal–lysosomal function, including Atp6ap1, Atp6ap2, Snx3, Snx15, Vps4a, Vps24, Vps29, Vta1, and Mp6r. Intriguingly, all of these genes were found to be upregulated in the APOE3/4 EC, which we hypothesize might represent a compensatory effect in response to a broad dysregulation of the endosomal–lysosomal system in the EC of these APOE3/4 mice. Importantly, none of these genes were shown to be differentially expressed in the PVC, suggesting that APOE4-mediated endosomal–lysosomal pathology may be occurring predominantly in AD-vulnerable brain regions such as the EC.

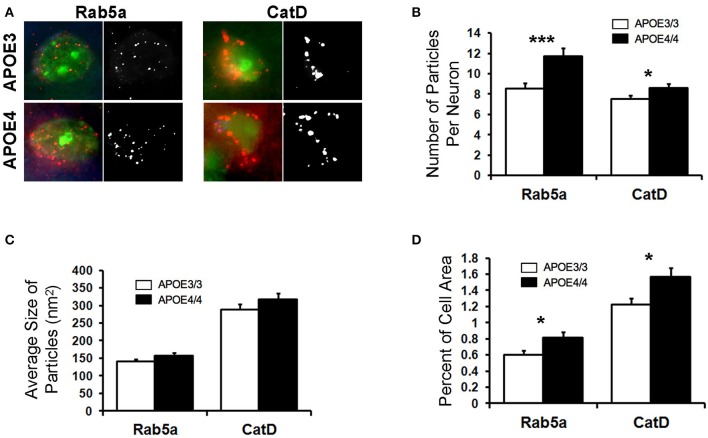

The morphology of endosomal–lysosomal compartments is altered in the brains of aged APOE4/4 mice

Abnormalities in the endosomal–lysosomal system are prominent in AD (see review by Nixon, 2017). Enlarged early endosomes are among the first cellular pathological features observed in AD pathogenesis (Cataldo et al., 2000, 2004; Nixon et al., 2000; Nixon, 2005), even prior to amyloid deposits in a given brain region, and AD-related enlarged early endosomes occur to a greater degree in the brains of APOE4 carriers (Cataldo et al., 2000). Building upon our transcriptomics findings and to determine whether endosomes are similarly affected by APOE4 expression in the absence of overt AD pathology, we investigated the endosomal–lysosomal system in the brains of 18-month-old APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 targeted replacement mice, as has been done in human tissue (Cataldo et al., 2000). 18-month-old APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice were chosen in order to gain a more robust picture of the endosomal–lysosomal changes observed in the transcriptomics results. Focusing initially on the EC of these mice, we quantified Rab5a immunolabeling of early endosomes in pyramidal neurons (Figure 4), as we have done previously on other AD-related mouse models (Choi et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2016). In APOE4/4 mice, we observed an increase in the mean number (8.5 ± 0.5 APOE3/3, 11.7 ± 0.8 APOE4/4 particles/cell; p = 0.0007; Figure 4B) and area fraction (0.6 ± 0.05% APOE3/3, 0.8 ± 0.07% APOE4/4 of cell area; p = 0.02; Figure 4D) of Rab5a-positive neuronal early endosomes when compared with age-matched APOE3 mice. No significant differences were seen in average endosomal size between the genotypes (140 ± 7.0 APOE3/3, 157 ± 8.0 APOE4/4 in nm2; p = 0.12; Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

The number and area fraction of Rab5a- and CatD-immunoreactive compartments are increased in the EC of aged APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice. Rab5a-immunoreactive early endosomes and CatD-immunoreactive lysosomes were quantified in the entorhinal cortex of 18 month-old APOE3/3 and APOE4/4 mice. (A) Representative images showing Rab5a and CatD immunolabeling (red), co-stained with Nissl (green). Black and white images were generated in ImageJ and used for quantification. (B–D) Quantification of average Rab5a- and CatD-positive compartment number (B), size (C), and area fraction (D) in APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice. (*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001).

To analyze the effect of APOE4 genotype on distal endosomal–lysosomal pathway compartments in neurons, we performed immunolabeling for cathepsin D (CatD), an acid protease that is localized primarily to lysosomes (Figure 4). As with the Rab5a-positive early endosomes, we saw an increase in the mean number (7.5 ± 0.3 APOE3/3, 8.6 ± 0.4 APOE4/4; p = 0.04; Figure 4B) and area fraction (1.2 ± 0.8 APOE3/3, 1.6 ± 0.11 APOE4/4; p = 0.02; Figure 4D) of CatD-positive compartments in the EC of APOE4/4 mice, as compared to APOE3/3 controls. Average size of the CatD-positive compartments was not changed between genotypes (288.5 ± 15.8 APOE3/3, 317.1 ± 22.3 APOE4/4; p = 0.22; Figure 4C).

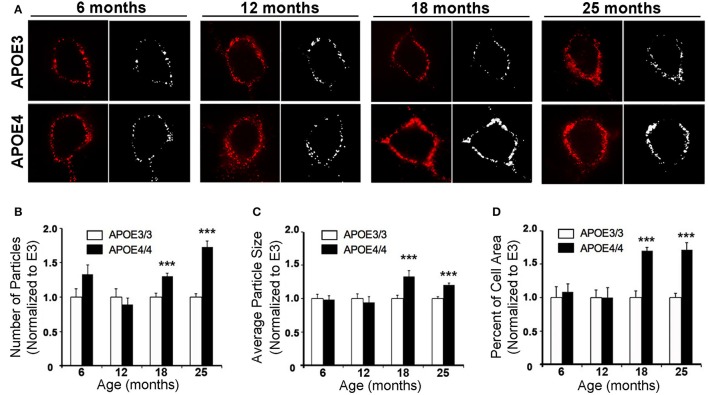

In order to further characterize the effect of APOE4 on early endosomes, we performed a larger study of Rab5a-positive early endosomes in the cingulate cortex of 6, 12, 18, and 25 month old APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice (Figure 5). The cingulate cortex was chosen because, like the EC, it is vulnerable to AD pathology (Leech and Sharp, 2014) and to APOE4-specific deficits (Valla et al., 2010). Additionally, we previously characterized early endosomal alterations in this region in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice (Choi et al., 2013) and, as it is larger than the EC, we anticipated that characterizing early endosomes in this region would facilitate our aging analysis. While no differences were seen in early endosome size, number or area fraction at 6 or 12 months of age, an increase in mean early endosome number (an increase of 30.5 ± 4.0%; Figure 5B), size (33.5 ± 8.0%; Figure 5C), and area fraction (70.1 ± 4.8%; Figure 5D) was seen in the 18 month-old APOE4/4 mice as compared to APOE3/3 controls, a difference that persisted in the 25 month-old animals (endosome number: 73.3 ± 8.4%; size: 20.7 ± 2.7%; area fraction: 71.8 ± 10.4%). This magnitude of early endosome change is similar to that which was reported in Down syndrome mouse models (Cataldo et al., 2003), and is similar to the APOE4-dependent early endosomal alteration seen in human neurons in the prefrontal cortex in early-stage AD (Cataldo et al., 2000).

Figure 5.

The number, size and area fraction of Rab5a-immunoreactive early endosomes are increased in the cingulate cortex of APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice with age. Rab5a-immunoreactive early endosomes were quantified in the cingulate cortex of 6, 12, 18, and 25 month-old APOE3/3 and APOE4/4 mice. (A) Representative images showing Rab5a immunolabeling (red). Black and white images were generated in ImageJ and used for quantification. (B–D) Quantification of average Rab5a-positive early endosome number (B), size (C), and area fraction (D) in APOE4/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice. (***p < 0.001; findings are normalized to the mean APOE3/3 value at each age in order to compare between age groups).

Discussion

Carriers of the ε4 allele of APOE are at a significantly increased risk of developing late-onset AD (Farrer et al., 1997). However, the exact cause of APOE4's association with AD is not fully understood. One potential mediator of APOE4's pathogenicity in AD may be disruption of the endosomal–lysosomal system, a process that is vital to cellular function and viability. Intriguingly, enlarged early endosomes are observed early in the pathogenesis of AD (Cataldo et al., 2000, 2004; Nixon et al., 2000; Nixon, 2005), and are present to a greater degree in the brains of APOE4 carriers (Cataldo et al., 2000). However, it is not clear if incipient AD pathology may play a role in the enlarged early endosome phenotype in APOE4 carriers. Interestingly, familial AD (FAD) caused by presenilin mutations does not exhibit the same abnormal endosomal phenotype (Cataldo et al., 2000), nor is presenilin mutation-induced FAD influenced by APOE genotype (Van Broeckhoven, 1995; Houlden et al., 1998), suggesting that amyloid pathology does not directly cause this early endosomal enlargement. While several studies have observed a deleterious effect of APOE4 on the fidelity of the endosomal–lysosomal system in vitro, the majority of these studies have been performed using immortalized cell lines with either exogenously added recombinant apoE protein or APOE overexpression systems (DeKroon and Armati, 2001; Ji et al., 2002; Yamauchi et al., 2002; Heeren et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2005; Rellin et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010; Li et al., 2012). Therefore, we sought to determine if APOE4 isoform expression impairs the endosomal–lysosomal pathway in an endogenous, in vivo setting that is free of AD pathology.

Using a well-characterized mouse model of human APOE isoform expression that does not develop amyloid plaques or neurofibrillary tangles (Sullivan et al., 1997, 2004), we were able to demonstrate that APOE4 expression directly causes endosomal–lysosomal system dysregulation using both transcriptomics and immunohistochemistry. In our RNA-sequencing analysis, we discovered an APOE4-dependent upregulation of a wide array of endosome and lysosome-related genes, including 9 V-type ATPases and 12 Rab GTPases, in the EC of aged APOE3/4 mice (Figure 3), which is suggestive of general endosomal–lysosomal pathway dysfunction. Furthermore, two of the Rab GTPase genes that we found to be upregulated in the transcriptomics analysis, the early endosome effector Rab5 and the late endosome effector Rab7, have also been found to be consistently upregulated in human cases of AD in selectively vulnerable neuronal populations (Ginsberg et al., 2010a,b, 2011). Additionally, gene expression of CatD is also upregulated in AD pyramidal neurons (Cataldo et al., 1995). Endosomal–lysosomal system abnormalities were confirmed through immunohistochemistry, which showed an increase in the size and area fraction of Rab5a-containing early endosomes and CatD-containing lysosomes in the EC of aged APOE4/4 mice (Figure 4). An age-dependent increase in the number, size and area fraction of Rab5a-containing early endosomes in the cingulate cortex of 18- and 25-month old (but not 6- and 12-month old) APOE4/4 mice (Figure 5) was also seen. Together, these findings demonstrate that APOE4 expression causes an age-dependent alteration in the endosomal–lysosomal system in the brain that is independent of overt AD pathology. Given the importance of the endosomal–lysosomal pathway in both the production of Aβ (see review by Thinakaran and Koo, 2008) and the clearance of pathogenic proteins (see review by Nixon, 2017), we believe that APOE4-associated endosomal–lysosomal system dysregulation may be an early instigator of AD pathogenesis among APOE4 carriers.

In addition to our observation of an enrichment in differentially expressed endosomal–lysosomal genes, our transcriptomics analysis revealed many other intriguing genes that were found to be differentially expressed in the EC of aged APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice, which we hope will spur additional research on the possible effects of these genes in APOE4-associated AD pathogenesis. The observation that differential APOE isoform expression affects two major developmental pathways (Hippo signaling and Wnt signaling; Figure 2) is of potential interest for APOE biology in general, since APOE4 has been shown to alter brain development, with infants carrying the APOE4 allele possessing region-specific differences in their white matter myelin water fractions (MWF) and gray matter volumes (GMV) compared to non-carriers (McDonald and Krainc, 2014) and juveniles carrying the APOE4 allele exhibiting reduced EC volumes compared to non-carriers (Shaw et al., 2007). Furthermore, APOE4 has been shown to inhibit Wnt signaling in vitro (Caruso et al., 2006).

Another intriguing finding was that several genes involved in the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation process (Atp5g1, Atp6ap1, Cox7b, Ndufa3, Ndufa4, Ndufb6, Ndufc2, Ndufv2, and Sdhd) are upregulated by APOE4. Although other studies have shown reduced glucose utilization in various brain regions of APOE4 carriers (Reiman et al., 1996, 2001, 2004), these results suggest that APOE4 may increase glucose-driven oxidative phosphorylation in the EC. In addition, we found a specific enrichment in genes that have previously been shown to be related to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis, including Mapt and Psenen. These results warrant further investigation to determine the roles of these important genes in APOE4-associated AD susceptibility.

In total, these findings inform on APOE neurobiology and how it may act to increase AD pathogenesis, most notably through a dysregulation of the endosomal–lysosomal system. In addition, we anticipate that the transcriptomics results presented here will facilitate additional research into the link between APOE4 and AD.

Author contributions

This study was designed and managed by TN, KP, PM, and KD. Animal care and breeding was performed by HF. RNA extraction, RNA-Sequencing and data processing was performed by TN and AD in the laboratory of MC. Pathway analysis was performed by TN in the laboratory of KD. Immunohistochemistry was performed by KP in the laboratories of PM and EL Quantification of endosomal and lysosomal compartments was performed by KP, AA, JuA, JaA, and TN. Manuscript preparation was performed by TN, KP, and PM with input from EL, MC, and KD.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Wai-Haung Yu for advice on this project, as well as Dr. Li Liu for assistance with tissue collection and Laidon Piroli for assistance with genotyping.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by a grant from NIA and NINDS to KD. (AG048408 and NS071836), fellowships from NIA (AG047797) and the Brightfocus Foundation (A2014200F) to TN, a grant from NIA (AG017617) to PM, training grants from NIGMS (GM066704) and NIA (AG052909) to KP, and funding from the Cure Alzheimer's Fund to KD and TN. In addition, this work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2017.00702/full#supplementary-material

Differentially expressed genes from the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

Differentially expressed genes from the PVC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

References

- Bales K. R., Verina T., Dodel R. C., Du Y., Altstiel L., Bender M., et al. (1997). Lack of apolipoprotein E dramatically reduces amyloid beta-peptide deposition. Nat. Genet. 17, 263–264. 10.1038/ng1197-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobinski M., de Leon M. J., Convit A., De Santi S., Wegiel J., Tarshish C. Y., et al. (1999). MRI of entorhinal cortex in mild Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 353, 38–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74869-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259. 10.1007/BF00308809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso A., Motolese M., Iacovelli L., Caraci F., Copani A., Nicoletti F., et al. (2006). Inhibition of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway by apolipoprotein E4 in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 98, 364–371. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano E. M., Prelli F., Wisniewski T., Golabek A., Kumar R. A., Soto C., et al. (1995). Fibrillogenesis in Alzheimer's disease of amyloid beta peptides and apolipoprotein E. Biochem. J. 306(Pt 2), 599–604. 10.1042/bj3060599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano J. M., Kim J., Stewart F. R., Jiang H., DeMattos R. B., Patterson B. W., et al. (2011). Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-beta peptide clearance. Sci. Transl. Med. 3:89ra57. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo A. M., Barnett J. L., Berman S. A., Li J., Quarless S., Bursztajn S., et al. (1995). Gene expression and cellular content of cathepsin D in Alzheimer's disease brain: evidence for early up-regulation of the endosomal-lysosomal system. Neuron 14, 671–680. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90324-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo A. M., Petanceska S., Peterhoff C. M., Terio N. B., Epstein C. J., Villar A., et al. (2003). App gene dosage modulates endosomal abnormalities of Alzheimer's disease in a segmental trisomy 16 mouse model of down syndrome. J. Neurosci. 23, 6788–6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo A. M., Petanceska S., Terio N. B., Peterhoff C. M., Durham R., Mercken M., et al. (2004). Abeta localization in abnormal endosomes: association with earliest Abeta elevations in AD and Down syndrome. Neurobiol. Aging 25, 1263–1272. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo A. M., Peterhoff C. M., Troncoso J. C., Gomez-Isla T., Hyman B. T., Nixon R. A. (2000). Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid beta deposition in sporadic Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 277–286. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64538-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Durakoglugil M. S., Xian X., Herz J. (2010). ApoE4 reduces glutamate receptor function and synaptic plasticity by selectively impairing ApoE receptor recycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12011–12016. 10.1073/pnas.0914984107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H., Kaur G., Mazzella M. J., Morales-Corraliza J., Levy E., Mathews P. M. (2013). Early endosomal abnormalities and cholinergic neuron degeneration in amyloid-beta protein precursor transgenic mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 34, 691–700. 10.3233/JAD-122143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter K., Stransky L., McGuire C., Forgac M. (2015). Recent insights into the structure, regulation, and function of the V-ATPases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 611–622. 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKroon R. M., Armati P. J. (2001). The endosomal trafficking of apolipoprotein E3 and E4 in cultured human brain neurons and astrocytes. Neurobiol. Dis. 8, 78–89. 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBattista A. M., Stevens B. W., Rebeck G. W., Green A. E. (2014). Two Alzheimer's disease risk genes increase entorhinal cortex volume in young adults. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:779. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman A. A., Cookson M. R., Galter D. (2016). ADAR2 affects mRNA coding sequence edits with only modest effects on gene expression or splicing in vivo. RNA Biol. 13, 15–24. 10.1080/15476286.2015.1110675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer L. A., Cupples L. A., Haines J. L., Hyman B., Kukull W. A., Mayeux R., et al. (1997). Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer disease meta analysis consortium. JAMA 278, 1349–1356. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg S. D., Alldred M. J., Counts S. E., Cataldo A. M., Neve R. L., Jiang Y., et al. (2010a). Microarray analysis of hippocampal CA1 neurons implicates early endosomal dysfunction during Alzheimer's Disease progression. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 885–893. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., Alldred M. J., Counts S. E., Wuu J., Nixon R. A., et al. (2011). Upregulation of select rab GTPases in cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 42, 102–110. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., Counts S. E., Wuu J., Alldred M. J., Nixon R. A., et al. (2010b). Regional selectivity of rab5 and rab7 protein upregulation in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 22, 631–639. 10.3233/JAD-2010-101080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. (2004). The role of apolipoprotein E in lipid metabolism in the central nervous system. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 1896–1906. 10.1007/s00018-004-4009-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser D. N., Dillman A. A., Ding J., Li Y., Cookson M. R. (2014). Post-translational decrease in respiratory chain proteins in the Polg mutator mouse brain. PLoS ONE 9:e94646. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren J., Grewal T., Laatsch A., Becker N., Rinninger F., Rye K. A., et al. (2004). Impaired recycling of apolipoprotein E4 is associated with intracellular cholesterol accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55483–55492. 10.1074/jbc.M409324200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson J. E., Vernier D. T. (1990). Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J. Lipid Res. 31, 545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman D. M., Bales K. R., Tenkova T., Fagan A. M., Parsadanian M., Sartorius L. J., et al. (2000). Apolipoprotein E isoform-dependent amyloid deposition and neuritic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2892–2897. 10.1073/pnas.050004797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman D. M., Herz J., Bu G. (2012). Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a006312. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlden H., Crook R., Backhovens H., Prihar G., Baker M., Hutton M., et al. (1998). ApoE genotype is a risk factor in nonpresenilin early-onset Alzheimer's disease families. Am. J. Med. Genet. 81, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. (2010). Abeta-independent roles of apolipoprotein E4 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 287–294. 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh T. V., Davis A. A., Ulrich J. D., Holtzman D. M. (2017). Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer's disease: the influence of apolipoprotein E on amyloid-beta and other amyloidogenic proteins. J. Lipid Res. 58, 824–836. 10.1194/jlr.R075481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z. S., Miranda R. D., Newhouse Y. M., Weisgraber K. H., Huang Y., Mahley R. W. (2002). Apolipoprotein E4 potentiates amyloid beta peptide-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 21821–21828. 10.1074/jbc.M112109200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Rigoglioso A., Peterhoff C. M., Pawlik M., Sato Y., Bleiwas C., et al. (2016). Partial BACE1 reduction in a Down syndrome mouse model blocks Alzheimer-related endosomal anomalies and cholinergic neurodegeneration: role of APP-CTF. Neurobiol. Aging 39, 90–98. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech R., Sharp D. J. (2014). The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain 137(Pt 1), 12–32. 10.1093/brain/awt162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Kanekiyo T., Shinohara M., Zhang Y., LaDu M. J., Xu H., et al. (2012). Differential regulation of amyloid-beta endocytic trafficking and lysosomal degradation by apolipoprotein E isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 44593–44601. 10.1074/jbc.M112.420224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Yee A., Brewer H. B., Jr., Das S., Potter H. (1994). Amyloid-associated proteins alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and apolipoprotein E promote assembly of Alzheimer beta-protein into filaments. Nature 372, 92–94. 10.1038/372092a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley R. W., Rall S. C., Jr. (2000). Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1, 507–537. 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshansky V., Rubinstein J. L., Gruber G. (2014). Eukaryotic V-ATPase: novel structural findings and functional insights. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 857–879. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J., Krainc D. (2014). Alzheimer gene APOE epsilon4 linked to brain development in infants. JAMA 311, 298–299. 10.1001/jama.2013.285400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S., Giordani B., Berent S., Frey K. A., Foster N. L., Kuhl D. E. (1997). Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 42, 85–94. 10.1002/ana.410420114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. A. (2005). Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 373–382. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. A. (2017). Amyloid precursor protein and endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: inseparable partners in a multifactorial disease. FASEB J. 31, 2729–2743. 10.1096/fj.201700359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. A., Cataldo A. M., Mathews P. M. (2000). The endosomal-lysosomal system of neurons in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: a review. Neurochem. Res. 25, 1161–1172. 10.1023/A:1007675508413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeck G. W., Reiter J. S., Strickland D. K., Hyman B. T. (1993). Apolipoprotein E in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: allelic variation and receptor interactions. Neuron 11, 575–580. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90070-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman E. M., Caselli R. J., Chen K., Alexander G. E., Bandy D., Frost J. (2001). Declining brain activity in cognitively normal apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 heterozygotes: a foundation for using positron emission tomography to efficiently test treatments to prevent Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3334–3339. 10.1073/pnas.061509598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman E. M., Caselli R. J., Yun L. S., Chen K., Bandy D., Minoshima S., et al. (1996). Preclinical evidence of Alzheimer's disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 752–758. 10.1056/NEJM199603213341202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman E. M., Chen K., Alexander G. E., Caselli R. J., Bandy D., Osborne D., et al. (2004). Functional brain abnormalities in young adults at genetic risk for late-onset Alzheimer's dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 284–289. 10.1073/pnas.2635903100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellin L., Heeren J., Beisiegel U. (2008). Recycling of apolipoprotein E is not associated with cholesterol efflux in neuronal cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1781, 232–238. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez G. A., Burns M. P., Weeber E. J., Rebeck G. W. (2013). Young APOE4 targeted replacement mice exhibit poor spatial learning and memory, with reduced dendritic spine density in the medial entorhinal cortex. Learn. Mem. 20, 256–266. 10.1101/lm.030031.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmechel D. E., Saunders A. M., Strittmatter W. J., Crain B. J., Hulette C. M., Joo S. H., et al. (1993). Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9649–9653. 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P., Lerch J. P., Pruessner J. C., Taylor K. N., Rose A. B., Greenstein D., et al. (2007). Cortical morphology in children and adolescents with different apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms: an observational study. Lancet Neurol. 6, 494–500. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. M., Mace B. E., Maeda N., Schmechel D. E. (2004). Marked regional differences of brain human apolipoprotein E expression in targeted replacement mice. Neuroscience 124, 725–733. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. M., Mezdour H., Aratani Y., Knouff C., Najib J., Reddick R. L., et al. (1997). Targeted replacement of the mouse apolipoprotein E gene with the common human APOE3 allele enhances diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17972–17980. 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinakaran G., Koo E. H. (2008). Amyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing, and function. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29615–29619. 10.1074/jbc.R800019200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valla J., Yaari R., Wolf A. B., Kusne Y., Beach T. G., Roher A. E., et al. (2010). Reduced posterior cingulate mitochondrial activity in expired young adult carriers of the APOE epsilon4 allele, the major late-onset Alzheimer's susceptibility gene. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 22, 307–313. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Broeckhoven C. (1995). Presenilins and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Genet. 11, 230–232. 10.1038/ng1195-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Michaelis M. L., Michaelis E. K. (2010). Functional genomics of brain aging and Alzheimer's disease: focus on selective neuronal vulnerability. Curr. Genomics 11, 618–633. 10.2174/138920210793360943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A. B., Valla J., Bu G., Kim J., Ladu M. J., Reiman E. M., et al. (2013). Apolipoprotein E as a beta-amyloid-independent factor in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers. Res. Ther. 5:38. 10.1186/alzrt204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi K., Tozuka M., Hidaka H., Nakabayashi T., Sugano M., Katsuyama T. (2002). Isoform-specific effect of apolipoprotein E on endocytosis of beta-amyloid in cultures of neuroblastoma cells. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 32, 65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. S., Stavrides P., Saito M., Kumar A., Rodriguez-Navarro J. A., Pawlik M., et al. (2014). Defective macroautophagic turnover of brain lipids in the TgCRND8 Alzheimer mouse model: prevention by correcting lysosomal proteolytic deficits. Brain 137(Pt 12), 3300–3318. 10.1093/brain/awu278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S., Huang Y., Mullendorff K., Dong L., Giedt G., Meng E. C., et al. (2005). Apolipoprotein (apo) E4 enhances amyloid beta peptide production in cultured neuronal cells: apoE structure as a potential therapeutic target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18700–18705. 10.1073/pnas.0508693102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Differentially expressed genes from the EC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

Differentially expressed genes from the PVC of APOE3/4 vs. APOE3/3 mice.

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptomics datasets generated during the current study are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, accession # GSE102334.