Abstract

Skeletal muscle metabolic function is known to respond positively to exercise interventions. Developing non-invasive techniques that quantify metabolic adaptations and identifying interventions that impart successful response are ongoing challenges for research. Healthy non-athletic adults (18–35 years old) were enrolled in a study investigating physiological adaptations to a minimum of 16 weeks endurance training prior to undertaking their first marathon. Before beginning training, participants underwent measurements of skeletal muscle oxygen consumption using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) at rest (resting muscleO2) and immediately following a maximal exercise test (post-exercise muscleO2). Exercise-related increase in muscleO2 (ΔmO2) was derived from these measurements and cardio-pulmonary peakO2 measured by analysis of expired gases. All measurements were repeated within 3 weeks of participants completing following the marathon and marathon completion time recorded. MuscleO2 was positively correlated with cardio-pulmonary peakO2 (r = 0.63, p < 0.001). MuscleO2 increased at follow-up (48% increase; p = 0.004) despite no change in cardio-pulmonary peakO2 (0% change; p = 0.97). Faster marathon completion time correlated with higher cardio-pulmonary peakO2 (rpartial = −0.58, p = 0.002) but not muscleO2 (rpartial = 0.16, p = 0.44) after adjustment for age and sex [and adipose tissue thickness (ATT) for muscleO2 measurements]. Skeletal muscle metabolic adaptions occur following training and completion of a first-time marathon; these can be identified non-invasively using NIRS. Although the cardio-pulmonary system is limiting for running performance, skeletal muscle changes can be detected despite minimal improvement in cardio-pulmonary function.

Keywords: endurance exercise, oxygen consumption, NIRS, skeletal muscle, VO2 kinetics

Introduction

Skeletal muscle metabolic adaptions with endurance exercise training are well-recognized (Gollnick et al., 1973; Holloszy and Booth, 1976). Recent studies implicate skeletal muscle metabolic dysregulation in disease and pre-disease states and a potential role for exercise in enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis has attracted recent interest (Lanza and Nair, 2009; Joseph et al., 2012). Skeletal muscle metabolic function is complex (Lanza and Nair, 2010) and studying muscle non-invasively is challenging. There is a pressing need to identify and apply sensitive, non-invasive measures of skeletal muscle metabolic function in order to investigate interventions that will deliver positive adaptations.

The effects of exercise training on the cardio-pulmonary system can be quantified using a cardio-pulmonary exercise test (CPET) to assess peak oxygen consumption (peak O2) via expired gas analysis. Multiple components contribute to peak O2 including: pulmonary diffusion, cardiovascular function (predominantly capacity to increase cardiac output, but also capacity for transport and exchange via the peripheral macro- and micro-circulation), the capacity for oxygen carrying in the blood, and cellular energy metabolism and mitochondrial function (Bassett and Howley, 2000). It is generally accepted that in humans, whole body peak O2, as measured by analysis of expired gases, is usually limited by the rate of oxygen delivery, and not by the rate of uptake/utilization in the muscle (Bassett and Howley, 2000). However, it remains unclear whether adaptation of one or other of these systems to a greater or lesser extent occurs. Previously, increased physical activity, but not necessarily heavy exercise training, has been show to enhance metabolic health independently of cardio-respiratory fitness (Laye et al., 2015).

Inclusion of a skeletal muscle assessments of oxygen consumption is uncommon within the context of a CPET. Vigelsø et al. (2014) have summarized evidence suggesting a direct positive correlation between improvements in peak O2 and muscle mitochondrial enzymatic activity. A limitation of these studies is that they require invasive muscle biopsy sampling and provide limited information about selected enzyme activity from a small tissue sample.

Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a non-invasive technique that can measure changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin (oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb) in skeletal muscle up to a depth of ~1.5 cm (Grassi and Quaresima, 2016; Jones et al., 2016). Applying an arterial occlusion above the NIRS measurement site allows skeletal muscle oxygen consumption (muscleO2) to be measured (Hamaoka et al., 1985). This has been shown to have good reproducibility (van Beekvelt et al., 2001; Lacroix et al., 2012). Indices previously described in studies using NIRS have been based on response to exercise with, or without, arterial occlusions. Without arterial occlusions it is impossible to differentiate changes in oxygen consumption from changes in blood flow. It is not feasible to perform repeated arterial occlusions to estimate O2 throughout exercise, so a simple alternative is to assume that immediately post-exercise the O2 determined via arterial occlusion is equivalent to the O2 during the final stages of the exercising protocol (Southern et al., 2014). Short, transient arterial occlusions have also been applied in the post-exercise period to determine the kinetics of muscleO2 recovery (Ryan et al., 1985a; Motobe et al., 2004) these measurements have shown good reproducibility and agreement (Southern et al., 2014) with established 31P-MRI measurements of muscle oxidative capacity (Ryan et al., 1985a).

We aimed to (1) describe non-invasive local measurements of muscleO2 in the gastrocnemius at rest and immediately after peak exercise using NIRS. (2) compare muscleO2 with cardio-pulmonary peak O2 assessed simultaneously by CPET, and (3) investigate the effect of ~6 months of endurance training in healthy individuals preparing for a first marathon on muscleO2 and cardio-pulmonary peak O2, and how these related to first-time marathon running performance.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were eligible for inclusion in this analysis if they had been enrolled in an observational study investigating the effect of first time marathon running on cardiac remodeling: The Marathon Study. Inclusion criteria for The Marathon Study were: age 18–35 years old at recruitment, no past significant medical history, no previous marathon-running experience, and current participation in running for <2 h per week. This analysis is a sub-study of The Marathon Study. Appendix 1 (Supplemental Information) shows full details of flow of participants through this study and selection for this analysis.

All measurements were carried out before training at ~6 months prior to the marathon (pre-training) and were repeated within a 3 week window following completion of the Marathon (post-training). The study design is shown in the diagram in Appendix 2 (Supplemental Information).

All procedures were in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki declaration, all participants gave written informed consent and the study was approved by the London—Queen Square National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee-−15/LO/0086.

Training

Participants were recommended to adhere to the “First-time finisher” training schedule (http://london-marathon.s3.amazonaws.com/vmlm2014/live/uploads/cms_page_media/1161/First-time-finisher-2017.pdf), aiming to run ~3 times per week for the 16 week period prior to the marathon. However, those eager to follow alternative, higher intensity, training plans were not discouraged. Some participants wished to start their training earlier than 16 weeks prior to the marathon and so we elected to conduct pre-training testing immediately following the release of the results from the ballot entry system which was 6 months prior to the marathon. Therefore, the minimum training period for all participants was 16 weeks but some participants may have trained for up to 26 weeks before the repeat assessment.

Anthropometric measurements

Participants were not asked to fast prior to either pre-training or post-training study visit but were asked to abstain from heavy exercise in the 24 h prior. We did not control for hydration during the study visits, however, participants were offered water throughout their visit but were asked not to have caffeinated drinks.

Height was measured barefoot using a standard stadiometer. Weight, body fat mass, and body fat percentage were measured using digital bio-impedance scales (BC-418, Tanita, USA) which have previously been shown to have good test-retest reproducibility (Kelly and Metcalfe, 2012). Body fat was included in this analysis because of the previously described substantial effect of adipose tissue thickness (ATT) on the NIRS signal (van Beekvelt et al., 2001).

Cardio-pulmonary exercise test

The CPET was carried out on a semi-supine ergometer (Ergoselect1200, Ergoline, Germany) using an incremental protocol standardized by bodyweight and gender. A semi-supine ergometer was used to allow concurrent echocardiography to be performed. Expired gases were analyzed throughout using a metabolic cart system (Quark CPET, COSMED, Italy). All participants were required to achieve a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) value above 1.1 during the CPT, however, the test was not terminated until the participant reported exhaustion or could no longer maintain the cycling cadence (~60–70 rpm).

Peak O2 was determined as the rolling 30 s average value between the final 15 s of exercise and first 15 s of recovery. Maximal predicted O2 was calculated according to the equation by Wasserman et al. (1999) and the percentage of this predicted value reached during the exercise test was calculated. Resting heart rate was measured using a 12-lead ECG conducted in the semi-recumbent position, 45° to the horizontal, following a 2–5 min resting period. Peak heart rate was the highest rolling 60 s average value during the final 30 s of exercise.

Skeletal muscle measurements

The gastrocnemius was selected for investigation because it is recruited during running and cycling (Zehr et al., 2007), it is therefore likely to undergo adaptations with training. NIRS measurements from this site have been shown to be reproducible (Southern et al., 2014) and since the calf is covered by less adipose tissue than the thigh or larger locomotive muscles (Bielemann et al., 2016) the influence of ATT on NIRS measurements is less (van Beekvelt et al., 2001). Prior to attaching the NIRS device, ATT was measured at the site of NIRS measurement using B-mode ultrasound (Vivid I, GE healthcare) equipped with a 12L-RS linear array transducer; three measurements were averaged.

A continuous wave NIRS device (Portamon, Artinis Medical Systems, Netherlands) was used to measure changes in oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb from the lateral gastrocnemius. Position and orientation of the device was standardized between individuals. The device was attached using tape and covered completely using a neoprene sleeve. Measurements were acquired at a frequency of 10 Hz throughout the protocol.

For NIRS measurements the participant was seated in a semi-upright position with their gastrocnemius relaxed. Arterial occlusions were performed at rest and immediately following the exercise test using a rapid inflation cuff (Hokanson, SC10D/E20, PMS Instruments, UK) placed on the thigh directly above the patellofemoral articulation. The cuff was inflated to a pressure of 250 mmHg and inflation or deflation was complete in 0.3 s. At rest the cuff was inflated for 30 s, post-exercise the occlusion duration was 5–8 s.

NIRS post-processing

Analysis of NIRS data was conducted using custom written programs in MATLAB R2014a (MathWorks Inc.). Signals were rejected if visual inspection showed movement artifact or if there was evidence that complete arterial occlusion had not be achieved. Incomplete arterial occlusion was judged on the absence of pulsatility in the oxy-Hb signal and the direction of the oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb signals; under complete arterial occlusion these are expected to move in opposite directions.

MuscleO2 was estimated by fitting the slope of the difference between oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb signal during each occlusion (Ryan et al., 1985b). More negative values represent higher muscle oxygen consumption; therefore, in order to align our values with the cardio-pulmonary peak O2, we inverted the values to provide a positive indices of muscle oxygen consumption. Exercise-related increases in muscleO2 (ΔmusO2) were calculated as the absolute difference between resting muscleO2 and muscleO2 measured immediately post-exercise.

Therefore, three indices of muscle function were calculated for each participant that represent oxygen consumption at different times; resting muscleO2, post-exercise muscleO2, and ΔmusO2. The units of these measurements are micoMolars of the hemoglobin difference signal per second (μM-Hbdiff/s).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data (i.e., gender) are presented as number (percentage) of participants. Continuous data were examined for normality and participant characteristics are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) if skewed. Results are presented as means (95% confidence intervals). Comparison of means was done using a paired Student's t-test and comparison of skewed data using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to assess correlations. Partial correlation coefficients (rpartial) were calculated for relationships between marathon completion time and peakO2 or muscleO2 after adjustment for age and gender, or age, gender, and log(ATT) as appropriate. To check for any possible gender differences in associations we included an interaction term in multivariable models and also undertook analyses stratified by gender. Gender stratified data are presented in the Appendix 3 (Supplemental Information); as no significant gender interactions were observed, we performed the primary analysis without stratification and present results as partial correlation coefficients with adjustment for gender but without interaction by gender. Statistical significance was assigned if P < 0.05.

Results

Participants

Twenty-seven participants provided complete data for analysis, participant characteristics are given in Table 1. The mean duration from completion of the marathon to the post-training visit was 15.8 ± 4.6 days.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at pre-training.

| Mean ±SD | Baseline (n = 27) |

|---|---|

| Gender male (%) | 17 (63) |

| Age (years) | 29.4 ± 3.5 |

| Height (cm) | 176.7 ± 10.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 72 ± 13 |

| Body fat mass (kg) | 15 ± 5.5 |

| ATTgastroc (cm) | 0.60 ± 0.22 |

Data are mean ± SD.

Muscle O2 and cardio-pulmonary peakO2

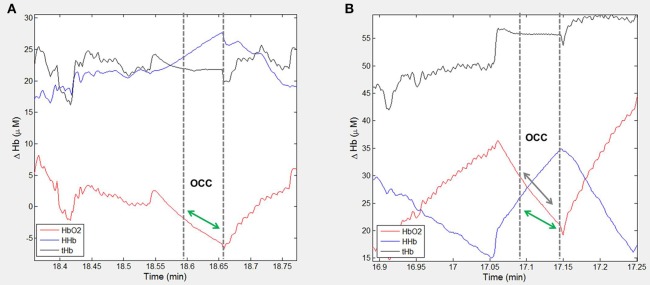

Pre-training higher post-exercise muscleO2 correlated with higher cardio-pulmonary peakO2 (Pearson's r = 0.64, p < 0.001; Figure 1). This correlation was marginally attenuated by adjustment for logATT (rpartial = 0.57, p = 0.002). Post-training a positive correlation was also seen but it was less strong [Pearson's r = 0.27, p = 0.17 (Figure 1); rpartial = 0.16, p = 0.4 after adjustment for logATT].

Figure 1.

Correlationbetween cardio-pulmonary peakO2 and post-exercise muscleO2 for 27 participants assessed pre-training and post-training. Participant data pre-training are represented by red circles and a red line of best fit and post-training by blue squares and a blue line of best fit.

Effect of endurance training

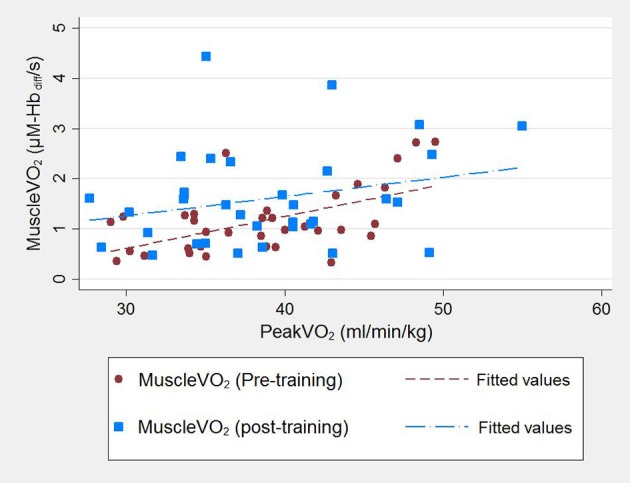

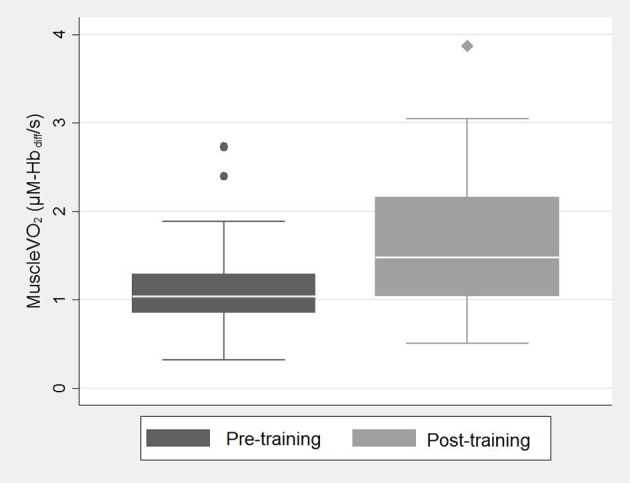

There was a small reduction in resting heart rate measured pre-training compared to post-training [mean difference = 1.4 (95% CI: −4.5, 7.2) bpm, p = 0.63; Table 2]. Cardio-pulmonary peakO2 did not change with training [mean difference = −0.0 (95% CI: −2.1, 2.0) ml.min.kg, p > 0.9; Table 2], but post-exercise muscleO2 was greater fpost-training compared to measurements pre-training [median value(IQR); 1.04(0.85–1.29) vs. 1.48(1.04–2.16), p = 0.004; Figure 2, Table 2]. Figure 3 shows example participant data of the NIRS signals during arterial occlusions (OCC) performed immediately post-exercise at the pre-training visit and post-training visits (Figures 3A,B, respectively). The dashed lines indicate the measurement area and green arrow indicates the slope of decline in HbO2 which represents rate of oxygen consumption in the muscle. The green arrow is shown at both time-points to highlight the change with training. ΔmusO2 was also greater post-training [mean difference = −0.79 (95% CI:−1.1, −0.46) μM-Hbdiff/s; p < 0.001]. There was a small reduction in resting muscle O2 [median value(IQR); 0.25(0.19–0.32) vs. 0.21(0.16–0.32), p = 0.35; Table 2].

Table 2.

Physiological response to exercise for all participants.

| Mean ±SD or Median (IQR) | Pre-training | Post-training | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 72.0 ± 13.0 | 72.0 ± 12.0 | 0.98 |

| BMI | 22.9 ± 2.9 | 23.0 ± 2.7 | 0.84 |

| Body fat mass (kg) | 15.0 ± 5.5 | 14.4 ± 6.2 | 0.30 |

| Resting HR (bpm) | 66 ± 13 | 64 ± 14 | 0.63 |

| Peak HR (bpm) | 167 (161–176) | 165 (157–171) | 0.29 |

| Peak VO2 (ml/min/kg) | 39.2 ± 5.7 | 39.2 ± 6.7 | 0.97 |

| Perc. pred. VO2 (%) | 94.1 ± 13.4 | 94.1 ± 13.5 | 0.98 |

| Resting muscle VO2 (μM-Hbdiff/s) | 0.25 (0.19–0.32) | 0.21 (0.16–0.32) | 0.35 |

| Post-Ex muscle VO2 (μM-Hbdiff/s) | 1.04 (0.85–1.29) | 1.48 (1.04–2.16) | 0.004 |

| ΔmusVO2 (μM-Hbdiff/s) | 0.88 ± 0.56 | 1.45 ± 0.94 | <0.001 |

Data are mean ± SD for normally distributed data and median(IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Comparison of means was done using a paired Student's t-test and comparison of skewed data using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Figure 2.

Box and whisker plot showing post-exercise muscleO2 pre-training (dark gray) and post-training (light gray). A box and whisker plot is used to describe this data because of its skewed distribution. The bottom and top of the box represent the first and third quartiles, the band inside the box is the median and the whiskers represent the lower and upper adjacent values within 1.5*IQR of the lower and upper quartile, respectively. Medians were compared using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test; follow-up values were significantly higher than baseline.

Figure 3.

Example participant data showing the NIRS signal during arterial occlusions (OCC) performed immediately post-exercise. Changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2), deoxygenated hemoglobin (HHb) and total hemoglobin (tHb) are shown for one participant at (A) pre-training visit and (B) post-training visit. The dashed lines indicate the measurement area and green arrow indicates the slope of decline in HbO2 which represents rate of oxygen consumption in the muscle. The green arrow is shown at both time-points to highlight the change with training.

Marathon performance

The mean marathon completion time was 4.6 ± 0.81 h. This was longer for women vs. men (4.9 ± 1.0 vs. 4.3 ± 0.6 h, p = 0.07). Based on weekly mileage data and marathon completion times from 27,000 runners over a 16 week training period (Reese et al., 2014) the average times achieved by participants in this study are consistent with a training schedule of between 6 and 13 miles/per week.

Higher cardio-pulmonary peakO2 values post-training were associated with faster marathon completion times after adjustment for gender and age (rpartial = −0.58, p = 0.002). Greater increases in peakO2 from the pre-training value also predicted shorter marathon completion times (rpartial = −0.53, p = 0.007). Table 3 shows individual participant peakO2 measured pre-training and post-training and the corresponding marathon completion time. There was no convincing relationship between post-exercise muscleO2 measured post-training and marathon completion time (rpartial = 0.31, p = 0.14) or ΔmusO2 and marathon completion time (rpartial = 0.31, p = 0.14).

Table 3.

Peak VO2 (ml/min/kg) is described for individual participants at the pre-training measurement visit and post-training.

| Peak VO2 (ml/min/kg) | Marathon time (h) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Post-training | |

| 39.22 | 39.87 | 3.43 |

| 36.46 | 47.13 | 3.48 |

| 44.62 | 46.40 | 3.52 |

| 42.11 | 43.04 | 3.71 |

| 42.95 | 49.14 | 3.82 |

| 38.59 | 41.81 | 3.98 |

| 33.70 | 33.64 | 4.04 |

| 40.00 | 40.54 | 4.14 |

| 35.05 | 36.60 | 4.14 |

| 47.10 | 49.28 | 4.15 |

| 49.51 | 54.96 | 4.27 |

| 43.56 | 37.21 | 4.28 |

| 38.91 | 42.70 | 4.31 |

| 34.30 | 38.25 | 4.41 |

| 45.70 | 33.67 | 4.48 |

| 34.73 | 34.45 | 4.70 |

| 34.29 | 35.33 | 4.73 |

| 43.22 | 41.63 | 4.73 |

| 33.90 | 37.04 | 4.79 |

| 38.52 | 40.51 | 4.85 |

| 48.29 | 33.47 | 5.03 |

| 29.43 | 31.39 | 5.04 |

| 41.28 | 40.55 | 5.12 |

| 31.17 | 30.20 | 5.22 |

| 45.45 | 42.99 | 5.54 |

| 35.06 | 28.45 | 6.37 |

| 29.82 | 27.69 | 6.86 |

Marathon completion time is also given.

Discussion

This study measured rest and post-exercise muscleO2 using NIRS simultaneously with an assessment of cardio-pulmonary peakO2 via CPET in a sample of young, healthy men and women before and after 4–6 months of endurance training in preparation for a first-time marathon. Compared with pre-training, post-training was associated with an increase in post-exercise muscleO2 and ΔmusO2, despite no detectable change in cardio-pulmonary peakO2.

The magnitude of the increase in muscleO2 was similar to that previously reported in healthy volunteers using NIRS following bicycle training (vastus lateralis; Sako, 2010) or training of arm muscles (Ryan et al., 2013), or using succinate dehydrogenase (Green et al., 1985) or citrate synthase (Burgomaster et al., 2008) as indicators of muscle oxidative capacity. However, one study failed to observe an increase in maximum muscle oxygen consumption in finger flexor muscles following 6 weeks of training with a dynamic handgrip exercise (Fujioka et al., 2012). Our findings suggest that, in these young, healthy individuals, a comparatively low-level of endurance training, while not sufficient to noticeably improve cardio-pulmonary function, still led to positive skeletal muscle adaptations resulting in improved oxygen extraction following exercise.

It is possible that the detected changes in gastrocnemius muscleO2 reflect changes in muscle group utilization due to training. Differences in training structure such as inclusion of strength, speed-endurance, or interval training in the program are known to differentially affect muscle function (Burgomaster et al., 1985; Milanović et al., 2015; Vorup et al., 2016). For example, it may be the case that participants replaced other activities (gym sessions, cycling, etc.) with run-training and therefore increased conditioning in the gastrocnemius. Post-exercise muscleO2 and the exercise-induced increase in muscle oxygen consumption, ΔmusO2, were moderately positively correlated with cardio-pulmonary peakO2 at the pre-training visit and more weakly at the post-training visit. Consequently, it seems likely that these correlations relate to participant characteristics (e.g., sex, age) rather than to the 6 months of training.

As expected faster marathon completion times were associated with higher cardio-pulmonary peakO2, (Joyner and Coyle, 2008) but no convincing relationship was observed between indices of muscle function, post-exercise muscleO2 and ΔmusO2, in gastrocnemius and marathon completion time. This is consistent with cardiopulmonary factors rather than skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative capacity (which typically exceeds maximal O2 supply) being a dominant factor in peak exercise capacity (Saltin and Calbet, 1985). Previously, cross-sectional data have demonstrated improved metabolic function in athletic vs. inactive subjects (Brizendine et al., 2013). In the study by Brizendine et al. (2013) highly trained endurance athletes, with a mean peak O2 = 73.5 ± 9.1 ml/min/kg, were compared to inactive individuals (mean peak O2 = 33.7 ± 5.9 ml/min/kg). Other studies also support positive adaptations related to exercise and physical activity (Nagasawa, 2013). However, in studies where arterial occlusions are not performed during the assessment of skeletal muscle function with NIRS, improvements could be attributed to either, or both, improved O2 delivery and/or increased mitochondrial capacity.

Limitations

We did not observe an improvement in peakO2 between pre-training and post-training which is contrary to expectation (Joyner and Coyle, 2008). It is possible that detraining following completion of the marathon may have contributed to this; however, the effect of short detraining periods is minimal (Mujika and Padilla, 2000) and is unlikely to fully explain this finding. It is possible that lack of a supervised structured training program, the comparatively moderate intensity of the recommended programme, and/or poor adherence by participants also contributed. Providing structured training programs and support throughout training was beyond the scope of this study. Appropriate methods of collecting information describing participant adherence to training programs (e.g., wearable activity monitors) would be warranted in future similar studies. Nevertheless, our objective was to observe changes that occur in “real-world” subjects undertaking their first marathon; therefore, our findings are likely to be representative of young, healthy adults undertaking endurance events for the first time. Esfarjani et al. randomized participants to structured high intensity training interventions vs. consistent low-intensity running and showed similar, non-significant, increases in peakO2 as we report here in the low-intensity group (Esfarjani and Laursen, 2007).

Monitoring training behaviors of the participants in the 6 months prior to the marathon would undoubtedly have provided additional valuable data. However, the objective of this analysis was to investigate if there is an effect of moderate endurance training on skeletal muscle metabolic function in healthy but untrained individuals. The effect of the extent of training was not investigated, although we acknowledge that is likely to have implications for the extent of improvement in skeletal muscle function. All participants included in this analysis completed the marathon and we believe it is fair to assume that this is evidence that, at least minimal, endurance training was undertaken.

Rejection of data due to noise in the NIRS signal was fairly high: ~12% pre-training and ~19% post-training. This could be improved in future studies by using higher cuff inflation pressures to ensure complete arterial occlusions and by preventing movement artifacts through use of a supportive-leg stand to ensure complete muscle relaxation.

Conclusion

In healthy individuals preparing for their first marathon participation in a 4–6 month training programme is associated with an increase in the ability of gastrocnemius skeletal muscle to utilize oxygen following exercise, implying an improvement in metabolic capacity. Metabolic adaptions can be identified non-invasively using NIRS combined with arterial occlusions within the setting of a supine CPET, although, caution is warranted regarding movement artifacts and insufficient occlusion pressures when using this technique. Post-exercise muscleO2 was positively correlated with cardio-pulmonary peakO2, particularly at pre-training, but, in terms of performance, cardio-pulmonary peakO2 is a better predictor of faster marathon running.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication. SJ: study design, data collection, and post-processing, statistical data analysis, manuscript preparation, and handling of the submission process. AD: study design, data collection, post-processing, and manuscript revisions. AB, GL, CM, and JM: study design, data collection, and manuscript revisions. SS: study design and manuscript revisions. AH: study design, data post-processing, statistical data analysis, and manuscript revisions.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Marathon Study participants for voluntarily giving up their time and undergoing detailed physiological measurements. We thank the Marathon Study team, who co-ordinated participant visits and performed clinical measurements, and Virgin Money London Marathon, particularly Hugh Brasher and Penny Dain, for their support with study advertisement and participant recruitment. In addition to the authors of this manuscript, The Marathon Study group includes the following clinical and research staff from St George's University of London, University College London and Bart's Health Trust: Jet Van Zalen, Camilla Torlasco, Amna Abdel Gadhir, Tom Treibel, Stefania Rosmini, Manish Ramlal, Nabila Mughul, Sunita Chauhan, Shino Kirokose, Tolu Akinola, Cheelo Simaanya, Lizette Cash, James Willis, David Hoare, James Malcolmson, Pamela de la Cruz, Annabelle Freeman, Delfin Encarnacion, Lesley Hart, Jack Kaufman, Frances Price, James Malcolmson, Rueben Dane, Karen Armado, Gemma Cruz, David Hoare, Lorna Carby, Tiago Fonseca, Fatima Niones, Zeph Fanton, Jim Pate, Joe Carlton, Sarah Anderson, Rob Hall, Sam Liu, Sonia Bains Claire Kirkby, Pushpinder Kalra, Raghuveer Singh, Bode Enam, Tee J Yeo, Rachel Bastiaenen, Della Cole, Jacky Ah-Fong, Sue Brown, Sarah Horan, Ailsa McClean, Kyle Conley and Paul Scully.

Footnotes

Funding. The Marathon Study was funded by the British Heart Foundation FS/15/27/31465, Cardiac Risk in the Young, and the Barts Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Centre. AH received other support from the British Heart Foundation (PG/15/75/31748, CS/15/6/31468, CS/13/1/30327); AH and JM received support from the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. The study also received support from COSMED, through the provision of cardio-pulmonary exercise testing equipment and technical support. The funders played no role in study design and conduct, or in these analyses, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2017.01018/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bassett D. R., Jr., Howley E. T. (2000). Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32, 70–84. 10.1097/00005768-200001000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielemann R. M., Gonzalez M. C., Barbosa-Silva T. G., Orlandi S. P., Xavier M. O., Bergmann R. B., et al. (2016). Estimation of body fat in adults using a portable A-mode ultrasound. Nutrition 32, 441–446. 10.1016/j.nut.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizendine J. T., Ryan T. E., Larson R. D., McCully K. K. (2013). Skeletal muscle metabolism in endurance athletes with near-infrared spectroscopy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 45, 869–875. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827e0eb6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgomaster K. A., Howarth K. R., Phillips S. M., Rakobowchuk M., Macdonald M. J., McGee S. L., et al. (2008). Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans. J. Physiol. 586, 151–160. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgomaster K. A., Hughes S. C., Heigenhauser G. J., Bradwell S. N., Gibala M. J. (1985). Six sessions of sprint interval training increases muscle oxidative potential and cycle endurance capacity in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 98, 1985–1990. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01095.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esfarjani F., Laursen P. B. (2007). Manipulating high-intensity interval training: effects on VO2max, the lactate threshold and m running performance in moderately trained males. J. Sci. Med. Sport.10, 27–35. 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M., Sako T., Kime R., Shimomura K., Osada T., Murase N., et al. (2012). Muscle endurance performance enhancement without increase in maximal muscle oxygen consumption. J. Jpn. Coll. Angiol. 52, 223–228. 10.7133/jca.52.223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gollnick P. D., Armstrong R. B., Saltin B., Saubert C. W., Sembrowich W. L., Shepherd R. E. (1973). Effect of training on enzyme activity and fiber composition of human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 34, 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi B., Quaresima V. (2016). Near-infrared spectroscopy and skeletal muscle oxidative function in vivo in health and disease: a review from an exercise physiology perspective. J. Biomed. Opt. 21:091313. 10.1117/1.JBO.21.9.091313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H. J., Jones S., Ball-Burnett M., Farrance B., Ranney D. (1985). Adaptations in muscle metabolism to prolonged voluntary exercise and training. J. Appl. Physiol. 78, 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaoka T., Iwane H., Shimomitsu T., Katsumura T., Murase N., Nishio S., et al. (1985). Noninvasive measures of oxidative metabolism on working human muscles by near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Appl. Physiol. 81, 1410–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy J. O., Booth F. W. (1976). Biochemical adaptations to endurance exercise in muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 38, 273–291. 10.1146/annurev.ph.38.030176.001421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Chiesa S. T., Chaturvedi N., Hughes A. D. (2016). Recent developments in near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for the assessment of local skeletal muscle microvascular function and capacity to utilise oxygen. Artery Res. 16, 25–33. 10.1016/j.artres.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A. M., Joanisse D. R., Baillot R. G., Hood D. A. (2012). Mitochondrial dysregulation in the pathogenesis of diabetes: potential for mitochondrial biogenesis-mediated interventions. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012:642038. 10.1155/2012/642038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner M. J., Coyle E. F. (2008). Endurance exercise performance: the physiology of champions. J. Physiol. 586, 35–44. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. S., Metcalfe J. (2012). Validity and reliability of body composition analysis using the tanita BC418-MA. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 15 Available online at: https://www.asep.org/asep/asep/JEPonlineDECEMBER2012_Kelly.pdf

- Lacroix S., Gayda M., Gremeaux V., Juneau M., Tardif J. C., Nigam A. (2012). Reproducibility of near-infrared spectroscopy parameters measured during brachial artery occlusion and reactive hyperemia in healthy men. J. Biomed. Opt. 17:077010. 10.1117/1.JBO.17.7.077010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza I. R., Nair K. S. (2009). Muscle mitochondrial changes with aging and exercise. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 467S−471S. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26717D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza I. R., Nair K. S. (2010). Mitochondrial metabolic function assessed in vivo and in vitro. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 13, 511–517. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833cc93d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laye M. J., Nielsen M. B., Hansen L. S., Knudsen T., Pedersen B. K. (2015). Physical activity enhances metabolic fitness independently of cardiorespiratory fitness in marathon runners. Dis. Markers 2015:806418. 10.1155/2015/806418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanović Z., Sporis G., Weston M. (2015). Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIT) and continuous endurance training for VO2max improvements: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Sports Med. 45, 1469–1481. 10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motobe M., Murase N., Osada T., Homma T., Ueda C., Nagasawa T., et al. (2004). Noninvasive monitoring of deterioration in skeletal muscle function with forearm cast immobilization and the prevention of deterioration. Dynamic Med. 3:2. 10.1186/1476-5918-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujika I., Padilla S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part I Short term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med. 30, 79–87. 10.2165/00007256-200030020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T. (2013). Slower recovery rate of muscle oxygenation after sprint exercise in long-distance runners compared with that in sprinters and healthy controls. J. Strength Cond. Res. 27, 3360–3366. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182908fcc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese R. J., Fuehrer D., Fennessy C. (2014). Runners With More Training Miles Finish Marathons Faster. [Web Page] Runners World [updated 2014]; Available online at: https://www.runnersworld.com/run-the-numbers/runners-with-more-training-miles-finish-marathons-faster.

- Ryan T. E., Erickson M. L., Brizendine J. T., Young H. J., McCully K. K. (1985b). Noninvasive evaluation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity with near-infrared spectroscopy: correcting for blood volume changes. J. Appl. Physiol. 113, 175–183. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00319.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T. E., Southern W. M., Brizendine J. T., McCully K. K. (2013). Activity-induced changes in skeletal muscle metabolism measured with optical spectroscopy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 45, 2346–2352. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829a726a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T. E., Southern W. M., Reynolds M. A., McCully K. K. (1985a). A cross-validation of near-infrared spectroscopy measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity with phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Appl. Physiol. 115, 1757–1766. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00835.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako T. (2010). The effect of endurance training on resting oxygen stores in muscle evaluated by near infrared continuous wave spectroscopy, in Oxygen Transport to Tissue XXXI, eds Takahashi E., Bruley D. F. (Boston, MA: Springer; ), 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltin B., Calbet J. A. (1985). Point: in health and in a normoxic environment, VO2max is limited primarily by cardiac output and locomotor muscle blood flow. J. Appl. Physiol. 100, 744–745. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01395.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern W. M., Ryan T. E., Reynolds M. A., McCully K. (2014). Reproducibility of near-infrared spectroscopy measurements of oxidative function and postexercise recovery kinetics in the medial gastrocnemius muscle. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 39, 521–529. 10.1139/apnm-2013-0347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beekvelt M. C., Borghuis M. S., van Engelen B. G., Wevers R. A., Colier W. N. (2001). Adipose tissue thickness affects in vivo quantitative near-IR spectroscopy in human skeletal muscle. Clin. Sci. 101, 21–28. 10.1042/cs1010021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigelsø A., Andersen N. B., Dela F. (2014). The relationship between skeletal muscle mitochondrial citrate synthase activity and whole body oxygen uptake adaptations in response to exercise training. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 6, 84–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorup J., Tybirk J., Gunnarsson T. P., Ravnholt T., Dalsgaard S., Bangsbo J. (2016). Effect of speed endurance and strength training on performance, running economy and muscular adaptations in endurance-trained runners. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 116, 1331–1341. 10.1007/s00421-016-3356-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman K., Hansen J. E., Sue D. Y., Casaburi R., Whipp B. J. (1999). Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: Including Pathophysiology and Clinical Applications. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams &Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr E. P., Balter J. E., Ferris D. P., Hundza S. R., Loadman P. M., Stoloff R. H. (2007). Neural regulation of rhythmic arm and leg movement is conserved across human locomotor tasks. J. Physiol. 582(Pt. 1), 209–227. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.