Abstract

Using the HIV-1 protease binding mode of MK-8718 and PL-100 as inspiration, a novel aspartate binding bicyclic piperazine sulfonamide core was designed and synthesized. The resulting HIV-1 protease inhibitor containing this core showed an 60-fold increase in enzyme binding affinity and a 10-fold increase in antiviral activity relative to MK-8718.

Keywords: HIV-1 protease inhibitors, MK-8718, PL-100, piperazine sulfonamide

HIV-1 protease is a critical enzyme in the lifecycle of the virus, serving to catalyze the proteolytic cleavage of polypeptide precursors into mature enzymes and structural proteins that are essential components of HIV-1.1 Inhibitors of this enzyme prevent conversion of HIV-1 particles into their mature infectious form, and so it follows that HIV-1 protease inhibitors represent an important therapeutic approach for the treatment of HIV-1 infection.2−4 Recently, we reported the discovery of MK-8718, an HIV-1 protease inhibitor containing a novel morpholine aspartate binding group.5 A key feature of this inhibitor is that the morpholine amine forms the key interaction with the Asp-25A and Asp-25B acidic residues of the enzyme, in contrast to the majority of inhibitors where a hydroxyl group plays this role.6 Herein we report further optimization of the enzyme bound conformation of these amine based class of inhibitors.

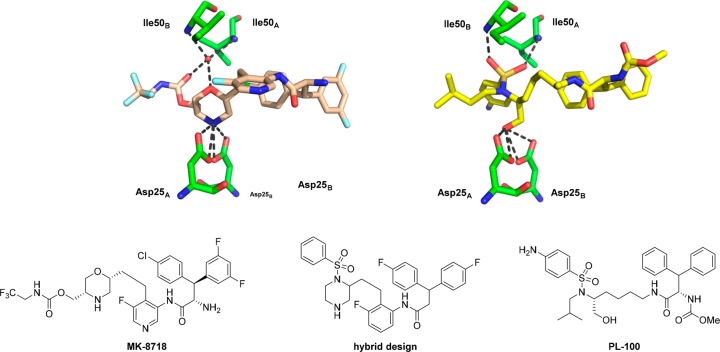

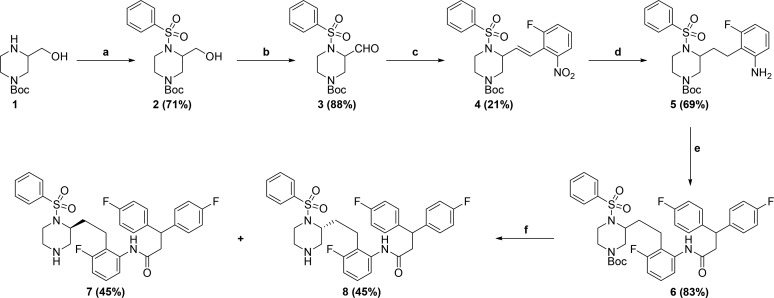

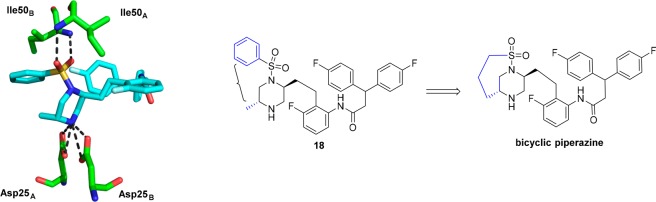

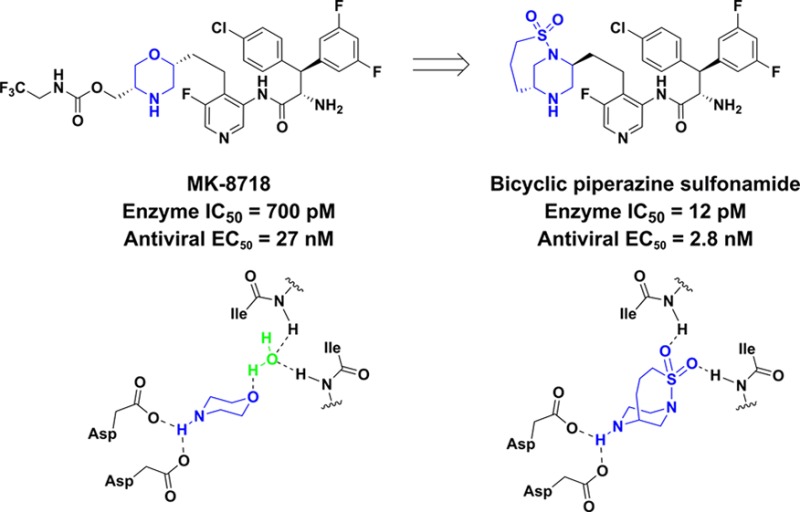

Inspiration for the design of our next generation inhibitors came from examining the enzyme bound conformations of MK-8718(5) and PL-100(7) (Figure 1). It can be seen that the morpholine oxygen of MK-8718 binds to the flap of the enzyme (Ile50A and Ile50B) via a bridging water. In contrast, the sulfonamide moiety present in PL-100 binds directly to the Ile50A and Ile50B residues. This observation led us to design the hybrid core shown below in Figure 1. The so-designed piperazine sulfonamide would retain the amine to form the key interaction with the Asp-25A and Asp-25B acidic residues, while the sulfonyl group would displace the bridging water and bind directly to the flap Ile50A and Ile50B residues. In order to simplify the synthesis of the initial proof of principal target, a simplified right-hand side derived from 3,3-bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid was utilized.8 Synthesis of our initial design is outlined in Scheme 1. Commercially available racemic 1 was sulfonylated to afford piperazine sulfonamide 2. Dess–Martin oxidation9 gave aldehyde 3, which underwent Wittig olefination using (2-nitrobenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide10 to afford olefin 4. Concomitant reduction of the nitro and olefin functionalities under hydrogenation conditions yielded aniline 5. Coupling of 3,3-bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid with aniline 5 afforded amide 6. Elaboration to the desired target was achieved by Boc-deprotection and resolution of the ensuing enantiomers to afford 7 and 8. Antiviral activity of both enantiomers 7 and 8 was measured, and pleasingly, enantiomer 7 showed significant activity in a cell-based antiviral assay (EC50 = 27 nM).11

Figure 1.

Hybrid design concept based on the binding modes of MK-8718 and PL-100 (PDB codes 5IVT and 2QMP).

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) PhSO2Cl, Hunig’s base, CH2Cl2, −78 °C to RT; (b) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (c) K2CO3, 18-crown-6, (2-nitrobenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide, DME, RT; (d) Pearlman’s catalyst, H2 balloon, CF3CH2OH, RT; (e) 3,3-Bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid, T3P, Hunig’s base, EtOAc, RT; (f) TFA, CH2Cl2, RT, then Chiralpak AD.

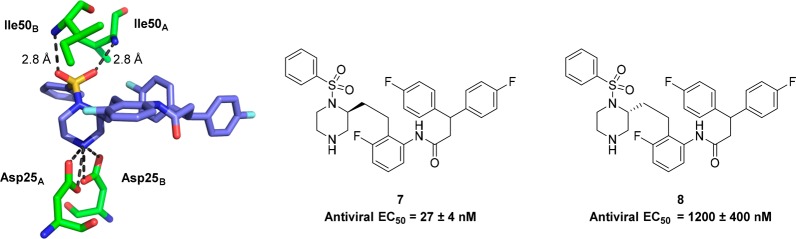

With this active compound in hand, we decided to pursue an X-ray crystal structure of 7 bound to HIV-1 protease to confirm our hypothesis that the sulfonamide moiety had displaced the water molecule present in the enzyme bound structure of MK-8718. Gratifyingly, the crystal structure of 7 bound to HIV-1 protease, shown in Figure 2, indeed showed that no bridging water was present, and the sulfone of 7 was directly hydrogen bonded to the Ile50A and Ile50B residues of the enzyme. Also evident from the crystal structure of 7 was that the preferred stereochemistry at the 2-position of the piperazine moiety was the (S)-configuration, opposite to that which is preferred for the morpholine core of MK-8718. This was in concurrence with results from earlier modeling studies of the piperazine sulfonamide core, which showed the HIV-1 protease binding conformation of the (S)-enantiomer to be lower in energy than that of the corresponding (R)-enantiomer.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of 7 bound to HIV-1 protease showing hydrogen bonding to Ile50A and Ile50B residues.

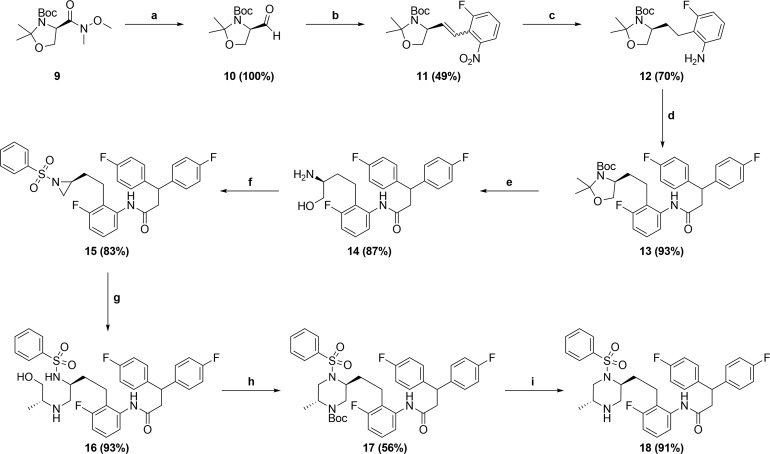

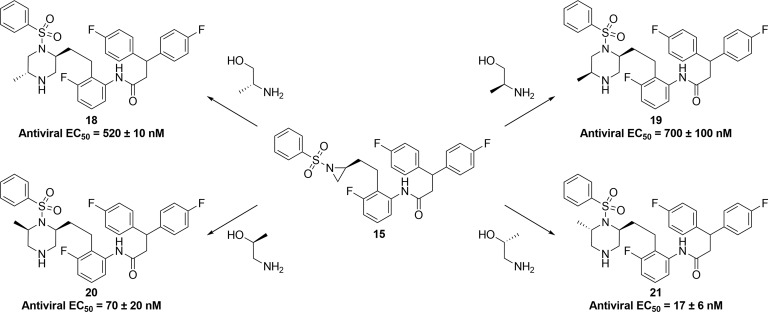

Although piperazine sulfonamide 7 displayed good antiviral activity, in vitro metabolic studies revealed that the unsubstituted left-hand side of the piperazine ring was susceptible to significant metabolic oxidation. This prompted us to investigate whether functionalization of the unsubstituted side of the piperazine ring would be tolerated with respect to antiviral activity. In order to introduce a methyl group on the left-hand side of the piperazine in a regio- and stereocontrolled manner, the route shown in Scheme 2 was utilized.12 The route starts with readily available and configurationally stable Weinreb amide 9. Reduction of 9 afforded aldehyde 10,13 which underwent Wittig olefination to give 11. Reduction of both the olefin and nitro groups afforded aniline 12, which was coupled with 3,3-bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid to afford amide 13. Deprotection of 13 afforded amino alcohol 14, which was converted to aziridine 15 via a sulfonylation and subsequent intramolecular Mitsunobu14 reaction. Opening of aziridine 15 with (R)-2-aminopropan-1-ol, followed by Boc-protection afforded 16, which was converted to piperazine 17 via an intramolecular Mitsunobu reaction. Boc-deprotection afforded the desired target 18. Aziridine 15 was used to synthesize all four methyl-substituted isomers as shown in Figure 3.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) LiAlH4, 2-Me-THF, 0 °C; (b) K2CO3, 18-crown-6, (2-nitrobenzyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide, DME, RT; (c) Pearlman’s catalyst, 50 psi H2, EtOAc/MeOH, RT; (d) 3,3-Bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid, T3P, Hunig’s base, EtOAc, RT; (e) TFA, H2O, CH2Cl2; RT; (f) (i) PhSO2Cl, NEt3, DMF, 0 °C; (ii) diazene-1,2-diylbismorpholinomethanone, PBu3, THF, RT; (g) (R)-2-aminopropan-1-ol, 1,2-DCE, 40 °C; (h) (i) Boc2O, NEt3, CH2Cl2, RT; (ii) diazene-1,2-diylbismorpholinomethanone, PBu3, THF, RT; (i) TFA, CH2Cl2, RT.

Figure 3.

Antiviral activity (EC50)11 of analogues 18–21 formed via amino alcohol opening of aziridine 15.

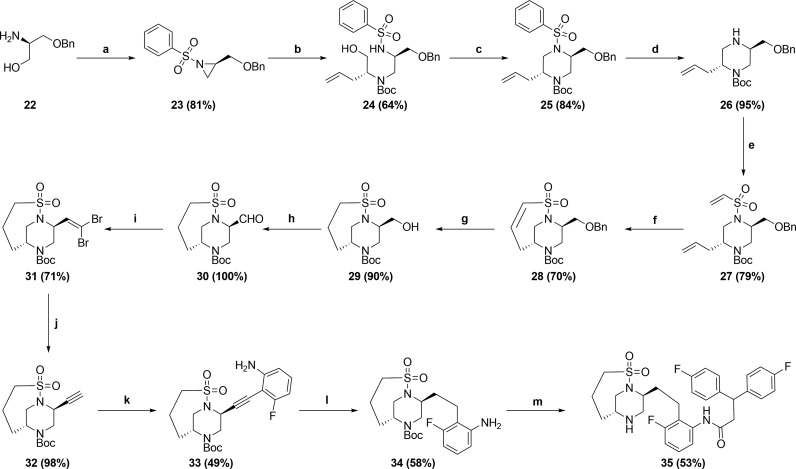

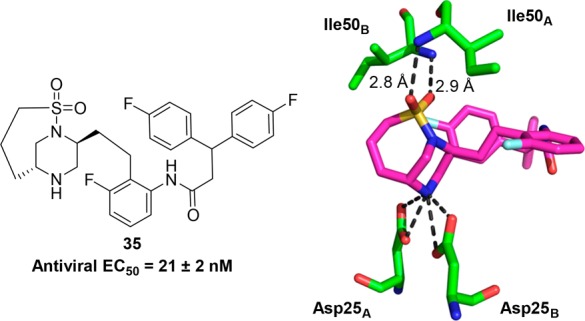

Although 20 and 21 with methyl substituents at the 6-position of the piperazine showed similar potency to unsubstituted piperazine 7, we were intrigued by the X-ray crystal structure of the less potent analogue 18 bound to HIV-1 protease, as shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that the phenyl group on the sulfonamide moiety and the methyl group on the piperazine ring lie in close proximity to each other, likely creating an unfavorable steric interaction in the binding conformation of the molecule. This observation led us to consider forming a bicyclic ring, with a bond joining the sulfone to the piperazine ring. Molecular modeling suggested a three carbon chain length would be optimal for locking the molecule in the bioactive conformation. Synthesis of this target is shown in Scheme 3 and began with commercially available amino alcohol 22. Aziridine formation via sulfonylation and Mitsunobu ring closure afforded intermediate 23. Aziridine 23 was opened with (R)-2-aminopent-4-en-1-ol, and subsequent Boc-protection yielded 24. An intramolecular Mitsunobu reaction gave piperazine 25, and subsequent magnesium/MeOH mediated deprotection15 cleanly removed the phenylsulfonyl moiety in the presence of both the N-Boc and O-Bn moieties to give 26. Sulfonylation of 26 gave metathesis precursor 27, which underwent ring closure mediated by Zhan Catalyst-1B16 to give bicyclic compound 28. Hydrogenation of 28 reduced the olefin and removed the benzyl group yielding 29. Dess–Martin oxidation, followed by Corey Fuchs alkyne formation17 via dibromide 31, afforded alkyne 32. Sonogashira coupling,18 followed by reduction of so-formed 33 afforded aniline 34. Coupling 3,3-bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid with aniline 34 and subsequent Boc-deprotection gave the bicyclic target 35. We were pleased to observe that bicyclic compound 35 retained good antiviral activity (EC50 = 21 nM).11 The X-ray crystal structure of 35 bound to HIV-1 protease, as shown in Figure 5, revealed the expected binding mode, whereby the sulfonyl group forms hydrogen bonds directly to flap Ile50A and Ile50B residues, taking the place of the bridging water present in the crystal structure of MK-8718 bound to HIV-1 protease.

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structure of 18 bound to HIV-1 protease, showing steric clash and leading to design of a bicyclic piperazine.

Scheme 3.

(a) (i) PhSO2Cl, NEt3, DMF, 0 °C; (ii) DIAD, PBu3, THF, 0 °C; (b) (i) (R)-2-aminopent-4-en-1-ol, THF, 45 °C; (ii) Boc2O, NEt3, CH3CN, 45 °C; (c) DIAD, PBu3, THF, RT; (d) Mg, MeOH, sonication, RT; (e) 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride, NEt3, CH2Cl2, RT; (f) Zhan Catalyst-1B, 1,2-DCE, 50 °C; (g) Pearlman’s catalyst, H2 balloon, EtOAc, RT; (h) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, RT; (i) PPh3, CBr4, CH2Cl2, RT; (j) EtMgBr, THF, 0 °C; (k) 3-fluoro-2-iodoaniline, (PPh3)2PdCl2, CuI, NEt3, CH3CN, 70 °C; (l) Pearlman’s catalyst, H2 balloon, EtOH, RT; (m) (i) 3,3-Bis(4-fluorophenyl)propanoic acid, T3P, Hunig’s base, EtOAc, RT; (ii) HCl, dioxane, RT.

Figure 5.

Antiviral activity (EC50)11 and X-ray crystal structure of 35 bound to HIV-1 protease.

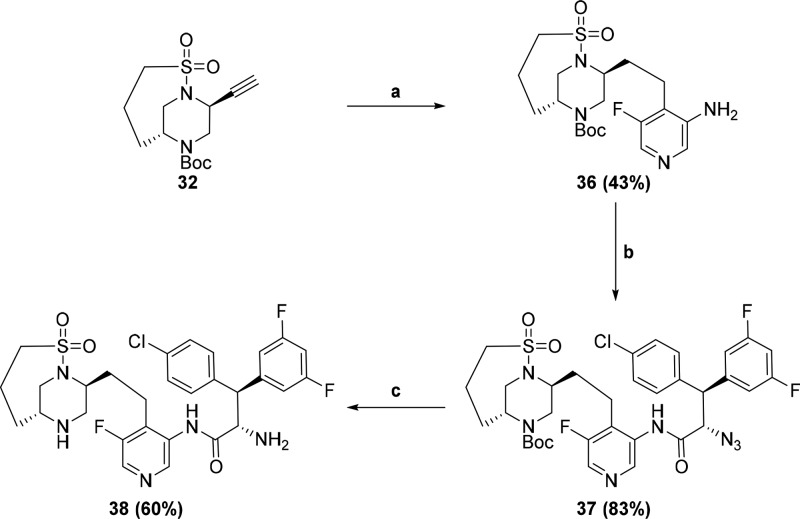

With this new core in hand, we decided to incorporate the highly optimized pieces of MK-8718 into a molecule. The synthesis was carried out starting with alkyne 32 as shown in Scheme 4. Sonogashira coupling, followed by reduction, afforded amine 36. Coupling of amine 36 with (2S,3S)-2-azido-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(3,5-difluorophenyl)propanoic acid5 gave amide 37, which, after azide reduction and Boc-deprotection produced the final compound 38. This compound showed exquisite enzyme binding affinity (IC50 = 12 pM) for HIV-1 protease, which translated into potent antiviral activity (EC50 = 2.8 nM) in a cell-based assay. As shown in Table 1, this represents a significant potency improvement relative to MK-8718 (binding IC50 = 700 pM, antiviral EC50 = 27 nM). In addition, the potency of 38 compares favorably to market leading HIV-1 protease inhibitors Atazanavir and Darunavir.

Scheme 4.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) 5-fluoro-4-iodopyridin-3-amine, (PPh3)2PdCl2, CuI, NEt3, CH3CN, 70 °C; (ii) Pearlman’s catalyst, H2 balloon, EtOH, RT; (b) (2S,3S)-2-azido-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(3,5-difluorophenyl)propanoic acid, POCl3, pyridine, 0 °C; (c) (i) PMe3, THF/H2O, 0 °C; (ii) HCl, dioxane/CH2Cl2, RT.

Table 1. Enzyme Affinity and Antiviral Activity of Key Molecules.

In summary, through a series of structure-based design iterations, a novel bicyclic piperazine sulfonamide aspartyl protease binding core was identified. This core produced a 60-fold increase in HIV-1 protease binding affinity and a 10-fold increase in antiviral activity relative to MK-8718.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- Ile

isoleucine

- Asp

aspartic acid

- Boc

tert-butyloxycarbonyl

- 1,2-DCE

1,2-dichloroethane

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- DME

1,2-dimethoxyethane

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- MeOH

methanol

- NEt3

triethylamine

- PBu3

tributylphosphine

- RT

room temperature

- T3P

1-propanephosphonic anhydride

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00386.

Synthetic experimental details for the synthesis of 7, 8, 18–21, and 35, descriptions of primary biological assays, procedures for cocrystallization studies, and a table of crystallographic statistics, along with in vivo rat pharmacokinetic data for 7, 18, 20, and 21 (PDF)

Accession Codes

X-ray crystallographic data for 7, 18, 19, 20, 21, and 35 bound to HIV-1 protease have been deposited in the RCSB protein data bank as 6B36, 6B3C, 6B3F, 6B38, 6B3G, and 6B3H, respectively.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Erickson-Viitanen S.; Manfredi J.; Viitanen P.; Tribe D. E.; Tritch R.; Hutchison C. A. 3rd; Loeb D. D.; Swanstrom R. Cleavage of HIV-1 gag polyprotein synthesized in vitro: sequential cleavage by the viral protease. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1989, 5 (6), 577–91. 10.1089/aid.1989.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl N. E.; Emini E. A.; Schleif W. A.; Davis L. J.; Heimbach J. C.; Dixon R. A. F.; Scolnick E. M.; Sigal I. S. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988, 85 (13), 4686–90. 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Osswald H. L.; Prato G. Recent progress in the development of HIV-1 protease inhibitors for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (11), 5172–5208. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midde N. M.; Patters B. J.; Rao P.; Cory T. J.; Kumar S. Investigational protease inhibitors as antiretroviral therapies. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2016, 25 (10), 1189–1200. 10.1080/13543784.2016.1212837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungard C. J.; Williams P. D.; Ballard J. E.; Bennett D. J.; Beaulieu C.; Bahnck-Teets C.; Carroll S. S.; Chang R. K.; Dubost D. C.; Fay J. F.; Diamond T. L.; Greshock T. J.; Hao L.; Holloway K. M.; Felock P. J.; Gesell J. J.; Su H.; Manikowski J. J.; McKay D. J.; Miller M.; Min X.; Molinaro C.; Moradei O. M.; Nantermet P. J.; Nadeau C.; Sanchez R. I.; Satyanarayana T.; Shipe W. D.; Sanjay S. K.; Truong V. L.; Vijayasaradhi S.; Wiscount C. M.; Vacca J. P.; Crane S. N.; McCauley J. A. Discovery of MK-8718, an HIV-1 protease inhibitor containing a novel morpholine aspartate binding group. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7 (7), 702–707. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskolski M.; Tomasselli A. G.; Sawyer T. K.; Staples D. G.; Heinrikson R. L.; Schneider J.; Kent S. B.; Wlodawer A. Structure at 2.5-A resolution of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease complexed with a hydroxyethylene-based inhibitor. Biochemistry 1991, 30 (6), 1600–9. 10.1021/bi00220a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandache S.; Coburn C. A.; Oliveira M.; Allison T. J.; Holloway M. K.; Wu J. J.; Stranix B. R.; Panchal C.; Wainberg M. A.; Vacca J. P. J. PL-100, a novel HIV-1 protease inhibitor displaying a high genetic barrier to resistance: an in vitro selection study. J. Med. Virol. 2008, 12, 2053–63. 10.1002/jmv.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari P. K.; Aidhen I. S. A. Weinreb amide based building block for convenient access to β, β- diarylacroleins: Synthesis of 3- arylindanones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 15, 2637–2646. 10.1002/ejoc.201600193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dess D. B.; Martin J. C. Readily accessible 12-I-5 oxidant for the conversion of primary and secondary alcohols to aldehydes and ketones. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 4155–4156. 10.1021/jo00170a070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmosin R. J.; Carson J. R.; Pitis P. M.. Preparation of octahydropyrrolo-[3,4-c]carbazoles useful as analgesic agents. WO9965911A1.

- Assay for inhibition of viral infection as described in the Supporting Information, run in the presence of 50% NHS; potency is reported as a EC50 (average of at least n = 2 runs).

- Crestey F.; Witt M.; Jaroszewski J. W.; Franzyk H. Expedited protocol for construction of chiral regioselectively N-protected monosubstituted piperazine, 1,4-diazepane building blocks. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74 (15), 5652–5655. 10.1021/jo900441s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura M.; Nakayama Y.; Kato T.; Ito Y. Gold(I)-catalyzed asymmetric aldol reaction of N-methoxy-N-methyl-α-isocyanoacetamide (α-isocyano Weinreb amide). An efficient synthesis of optically active β-hydroxy α-amino aldehydes and ketones. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1727–1732. 10.1021/jo00111a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta K.; Panda G. Regioselective ring-opening of amino acid-derived chiral aziridines: an easy access to cis-2,5-disubstituted chiral piperazines. Chem. - Asian J. 2011, 6, 189–197. 10.1002/asia.201000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyasse B.; Grehn L.; Ragnarsson U. Mild, efficient cleavage of arenesulfonamides by magnesium reduction. Chem. Commun. 1997, 11, 1017–1018. 10.1039/a701408b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Z.Preparation of ruthenium complex ligand, ruthenium complexes, supported ruthenium complex catalysts for olefin metathesis. WO 2007003135A1.

- Corey E. J.; Fuchs P. L. Synthetic method for conversion of formyl groups into ethynyl groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 36, 3769–72. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)94157-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonogashira K. Development of Pd-Cu catalyzed cross-coupling of terminal acetylenes with sp2-carbon halides. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 653 (1–2), 46–49. 10.1016/S0022-328X(02)01158-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assay for inhibition of HIV-1 protease as described in the Supporting Information; potency is reported as an IC50 (average of at least n = 2 runs).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.