Abstract

Background:

This study was carried out to enumerate the level of difference in functional impairment and quality of life (QOL) in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) patients and normal control group to find out the relationship among ICD functional impairment and QOL.

Methodology:

Thirty patients diagnosed with OCD as per International Classification of Diseases Diagnostic Criteria for Research-10 were taken for study. The control group consists of 30 normal participants from the community. Functional impairment and QOL questionnaires were administered on both groups to measure functional impairment and QOL in OCD.

Results:

The mean age of onset of OCD was (23.8 ± 7.25), mean duration of illness was (6.3 ± 4.47), and mean duration of treatment was (2.56 ± 2.47). It was also observed that total score as well as all the domains of the World Health Organization QOL-BREF, OCD patients scored significantly less (P < 0.001) compared to normal controls. Dysfunctional Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ)-Social area and DAQ-Personal area had statistically significant positive correlation (P < 0.05) with an obsessive subscale of Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) whereas DAQ-social area (P < 0.05), DAQ-Personal Area (P < 0.05) had statistically significant positive correlation with a total score of Y-BOCS.

Conclusion:

The presence of functional impairment leads to poor QOL in the persons with OCD.

Keywords: Functional impairment, obsessive compulsive disorder, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is the fourth most common psychiatric disorder, occurring in 2%–3% of the U.S. population.[1] The lifetime prevalence of OCD is estimated to 1%–3% based on population-based surveys. OCD is a chronic and disabling illness that impacts negatively on the academic, occupational, social, and family function of patients.[2]

The course of OCD is typically chronic, with an increase of symptoms often associated with stressful life events.[3] Finally, whereas effective treatments have been developed, many sufferers either fail to respond, respond partially, or relapse shortly after pharmacological treatment[4,5] Such chronicity has led to the widespread view that OCD is associated with significant functional impairment and reduced quality of life (QOL). However, the range and degree of OCD-specific psychosocial dysfunction among affected adults have not yet to be systematically documented.

QOL is increasingly recognized as a pivotal outcome parameter in research on OCD. Studies using generic (i.e., illness-unspecific) instruments have confirmed poor QOL in OCD patients across a wide range of domains, especially with respect to social, work, role functioning, and mental health aspects. Depression and obsessions are the symptom clusters that most strongly contribute to low QOL. Scores are sometimes as low as those obtained by patients with schizophrenia.

Dysfunction can be found in QOL and functional impairment in OCD. However, there is a lack of data in the adult patients with OCD. Furthermore, there is a dearth of literature on the correlation between the QOL and functional impairment. Thus, the present study was focus on the functional impairment and QOL of a patient with OCD and find out the relationship among these variables. The finding will be helpful and useful in the management of this group to prevent from further deterioration of disease process.

METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted on the individuals visiting the OCD clinic scheduled once weekly in Psychosocial Unit as well as in outpatient department and inpatient department during September 2008–January 2010 at the Central Institute of Psychiatry, Kanke, Ranchi. Thirty patients diagnosed with OCD as per International Classification of Diseases Diagnostic Criteria for Research (ICD-10, DCR)[6] were included in the study and 30 normal individuals taken as control. Inclusion criteria for the case were (1) patient diagnosed with OCD as per ICD-10, DCR,[6] (2) age range 18–60 years and both sex, and (3) the patient who gave written informed consent. The inclusion criteria for the normal control group were match with age, sex, and education and the individual having General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 score <3. Exclusion criteria were (1) patient diagnosed with other psychiatric illness except mild to moderate depression, (2) comorbidity medical, physical or organic disorder, and (3) Age <18 and more than 60. The exclusion criteria for the control group were (1) GHQ >3, (2) Comorbidity medical, physical, or organic disorder, and (3) age <18 and more than 60.

Patients with diagnosis of OCD as per ICD-10, DCR[6] criteria were selected from OCD clinic on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the details of the study.

The scales like–Dysfunctional Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ), World Health Organization QOL scale (WHO-QOL-1996 Hindi version),[5] Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) (Goodman et al. 1992)[7] were administered on the patients.

The statistical analyses were done with SPSS Inc. Released 2007, Version 16.0. Chicago. The operating system used was window 7. Description of sample characteristics was done using descriptive statistics- percentage, mean and standard deviation. Pearson correlation was done to study the association between Y-BOCS scores with DAQ, WHO-QOL. The level of statistical significance was kept at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

RESULTS

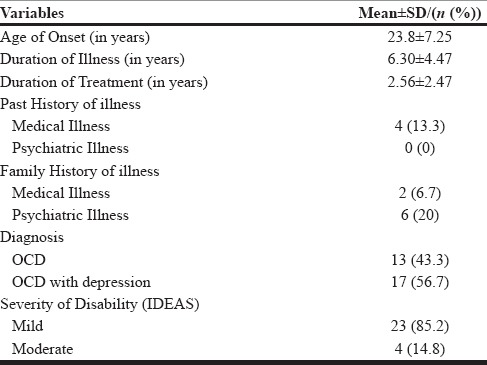

The mean age of onset of OCD was (23.8 ± 7.25), mean duration of illness was (6.3 ± 4.47), mean duration of treatment was (2.56 ± 2.47), (13.3%) of the patients had previous history of medical illness, no history of psychiatric illness and 56.7% of the patients had depression. 6.7% has a family history of Medical illness, and 20% has a family history of psychiatric Illness [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of OCD patients (N=30)

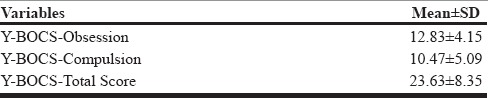

The severity of OCD was found to be severe in the obsessive subscale of Y-BOCS (mean = 6.07 ± 2.60), compulsive subscale of Y-BOCS (mean = 10.47 ± 5.09) and total Score of Y-BOCS (mean = 23.63 ± 8.35) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Scores obtained by Obsessive compulsive disorder patients (N=30) in different areas of Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

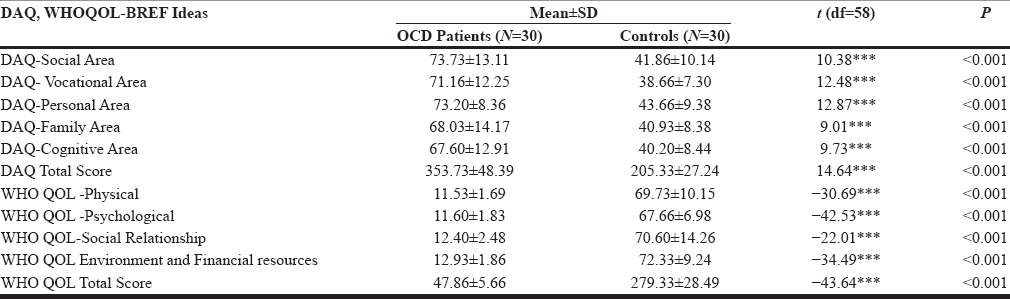

This table shows the group differences in DAQ Scores between OCD patients and normal controls groups. Statistically, significance difference was found between OCD patients and normal control (P < 0.001) in all the domains of DAQ. It was also observed that in total score as well as all the domains of WHOQOL-BREF, OCD patients scored significantly less compared to normal controls (P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Group differences in Dysfunctional Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ), World Health organization Quality of life- BRIEF (WHOQOL-BREF) Scores between OCD patients and normal controls

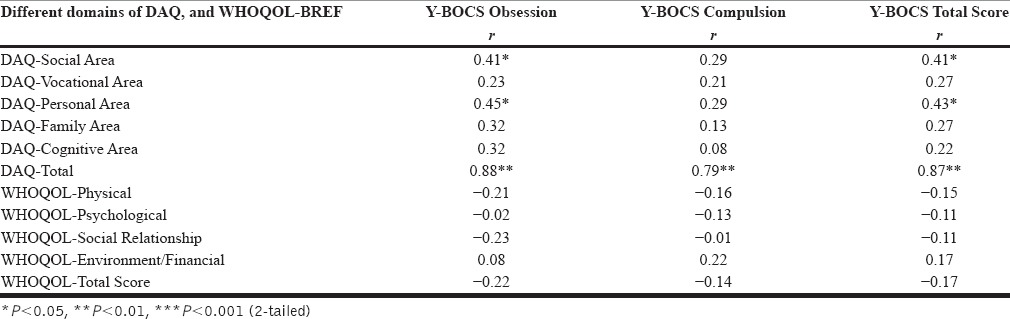

This table shows the correlation between scores of Y-BOCS with scores in different areas of DAQ, WHOQOL-BREF, in OCD patients (n = 30). It was observed that DAQ-Social Area (P < 0.05), DAQ-Personal Area (P < 0.05) had statistically significant positive correlation with obsessive subscale of Y-BOCS whereas DAQ-Social Area (P < 0.05), DAQ-Personal Area (P < 0.05) had statistically significant positive correlation with total score of Y-BOCS. DAQ-Total area was positively correlated with an obsessive subscale of Y-BOCS, compulsive subscale of Y-BOCS, total score of Y-BOCS. While the interpersonal activities of IDEAS have statistically significant correlation (P < 0.05) with total score of Y-BOCS [Table 4].

Table 4.

Correlation of Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) scores with scores of Dysfunctional Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ), World Health Organization Quality-of-Life-BREF obsessive-compulsive disorder patients (n=30)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported that significantly higher degree of functional impairment in OCD than healthy control. Particularly, the OCD patients had shown marked impairments in all areas of dysfunction measuring scale such as social, vocational, personal, family, and cognitive areas. This particular finding has also been found to be consistent with the observations made by earlier researchers regarding the dysfunction in OCD.[8,9,10,11]

The social dysfunction in OCD patients had shown dysfunction, and that dysfunction has been emerged as a major impediment to their social life. This finding was similar to the findings of previous studies.[9,12] Cooper (1996) reported persistence of OCD or complications in the course could cause “great” interference in family social activities of the affected people.[7] These authors reported that patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were found to have significantly more impairment at work, in social relationships, and at leisure. As OCD patient having higher levels of self-reported depression and anxiety and the patient had greater influence on emotional adjustment and particularly on self-reported anxiety.[13] Although these individuals did not show the syndromal diagnosis of OCD, some areas of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder do have commonalities with OCD.

OCD patients do also suffer impairment in their vocational or occupational functioning. Previous studies showed that occupational functioning was heavily affected by the presence of OCD; the patients showed significantly lower vocational functioning than the normal persons both in terms of quality and quantity.[14,15] Stein et al. made an observation that getting into the socialization process and maintaining the family relationships were the two most vulnerable areas which were affected by OCD.[16] These authors reported that OCD patients tended to develop either moderate or severe level of dysfunction in these two areas (60.5% and 59%, respectively). In addition to that severe or moderate interference with work was reported by 40% and in academic areas by 54.5% OCD patients).[16] In the present study, OCD patients had been found to have marked incapacity, and they scored significantly lower than the normal control group in this personal domain of DAQ. Previous researchers also found the same finding regarding this area, and they mentioned that intractable OCD might cause a very severe negative impact on the sufferers’ personal and interpersonal functions.[17] The domain of cognitive area found significant dysfunction in OCD group than controls as found by previous studies.[8,18] In some severe cases of OCD, patients may also develop considerable neuropsychological skills deficits in the forms of memory impairment, inability in decision-making, poor set shifting, poor motor, and cognitive inhibitory mechanisms.[11,18] Lawrence et al. (2006) observed that patients with prominent hoarding symptoms showed marked impairment in cognitive functioning such as decision-making ability and set shifting abilities.[19]

Family Area domain found significantly lower in OCD group than normal controls. This finding of the present study also has consistency with the findings of previous researchers.[15,20] Cooper (1996) reported that OCD patients have to face “great” interference in their family and social activities. This interference often leads to loss of friendships, marital discord, financial problems, family turmoil, interpersonal difficulties, and hardship on siblings. Jayakumar et al. noted deterioration in the quality of relationship of OCD patients with other family members, friends, and family stability, although the degree of impairment was comparable to that of schizophrenia.[21] However, one study we found as a contrast to our finding where family dysfunction was associated with more with ADHD but not with OCD.[22]

In total score as well as in all the domains of DAQ, statistically significance difference was found between OCD patients and normal control (P < 0.001) as found by the previous studies.[12,23] These groups differed significantly with regard to global dysfunction as well. This finding is in conformity with the results of the study by Bannon et al.

In the present study, it was also observed that in total score as well as all the domains of WHOQOL-BREF, physical, psychological, social relationship, environment and financial resources, OCD patients scored significantly less compared to normal controls (P < 0.001), which was supported by different previous studies.[24,25] This is probably the development of depression in OCD. This could imply that patients with OCD are at high risk for physical complications and consequently tend to perceive their physical QOL as poorer than the general population.[18,26]

On QOL measures, OCD patients had the lowest scores on the psychological health domain, which includes items on body image and appearance. OCD patients’ preoccupation with their appearance and cleanliness of body parts might have contributed to their poor assessment of QOL.

It is notable that OCD patients in the present study had relatively low scores in the social relationship domain, this consistent finding reported by previous studies.[24,27] This finding might be due to fear of criticism or may be associated with cluster C personality disorder.

Limitation and future direction

The limitation in our study that it was a cross-section study

The purposive sampling design left room for potential selection bias precluding generalization of the findings of the study. The study was a hospital-based study. Only those patients who came to utilize the hospital services were assessed. OCD patients live in a high number in the community, and many of them do not come to the hospital for treatment; many of them have not been treated so far. A community-based approach would have taken them into the study

Participants were treatment seeking, and therefore, our findings may not apply to those individuals with OCD who do not seek treatment. In addition, subjects were evaluated at only one-time point. The relationship between changes in OCD symptoms and changes in specific domains of QOL can best be assessed over time. Continued observation of the study participants will allow us to more fully understand the interaction between severity of OCD and its impact on QOL over time

A community-based study should be done which would provide more generalizable findings. Moreover, family views, housing and living conditions, social support could be more objectively and comprehensively assessed then

A longitudinal design is required to better identify the possible bidirectional Pathways between symptom functioning and QOL, as well as the stability of these associations over time

Additional research is needed to assess which aspects of QOL and psychosocial functioning are helped by pharmacologic and cognitive-behavioral therapy so that specific treatments can be targeted to specific psychosocial functioning deficits.

CONCLUSION

Among clinical parameters the total score as well as in all the domains of Dysfunctional Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ), statistically significance difference was found between OCD patients and normal control. It was also observed that the total score as well as all the domains of WHOQOL-BREF, OCD patients scored significantly less compared to normal controls. It was also observed that DAQ-Social Area, DAQ-Personal Area had statistically significant positive correlation with Obsessive subscale and total score of YBOCS. DAQ-Total area was positively correlated with obsessive and compulsive subscale of YBOCS.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1094–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollander E, Kwon JH, Stein DJ, Broatch J, Rowland CT, Himelein CA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders: Overview and quality of life issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 8):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cromer KR, Schmidt NB, Murphy DL. An investigation of traumatic life events and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1683–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Schwartz SA, Furr JM. Symptom presentation and outcome of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1049–57. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxena S, Brody AL, Schwartz JM, Baxter LR. Neuroimaging and frontal-subcortical circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;173:26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper M. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Effects on family members. The Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:296–304. doi: 10.1037/h0080180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramowitz JS, Storch EA, Keeley M, Cordell E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with comorbid major depression: What is the role of cognitive factors? Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:276–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buhlmann U, Deckersbach T, Engelhard I, Cook LM, Rauch SL, Kathmann N, et al. Cognitive retraining for organizational impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao NP, Reddy YC, Kumar KJ, Kandavel T, Chandrashekar CR. Are neuropsychological deficits trait markers in OCD? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1574–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Keller M, McCracken J. Functional impairment in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(Suppl 1):S61–9. doi: 10.1089/104454603322126359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasudev RG, Yallappa SC, Saya GK. Assessment of quality of life (QOL) in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and dysthymic disorder (DD): A comparative study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:VC04–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/8546.5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancebo MC, Eisen JL, Pinto A, Greenberg BD, Dyck IR, Rasmussen SA. The brown longitudinal obsessive compulsive study: Treatments received and patient impressions of improvement. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1713–20. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bannon S, Gonsalvez CJ, Croft RJ, Boyce PM. Executive functions in obsessive-compulsive disorder: State or trait deficits? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:1031–8. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein DJ, Bouwer C, van Heerden B. Pica and the obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. S Afr Med J. 1996;86(12 Suppl):1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabe HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, Rumpf HJ, Freyberger HJ, Dilling H, et al. Prevalence, quality of life and psychosocial function in obsessive-compulsive disorder and subclinical obsessive-compulsive disorder in Northern Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;250:262–8. doi: 10.1007/s004060070017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moritz S, Rufer M, Fricke S, Karow A, Morfeld M, Jelinek L, et al. Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder before and after treatment. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:453–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence NS, Wooderson S, Mataix-Cols D, David R, Speckens A, Phillips ML. Decision making and set shifting impairments are associated with distinct symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:409–19. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy BL, Lin Y, Schwab JJ. Work, social, and family disabilities of subjects with anxiety and depression. South Med J. 2002;95:1424–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayakumar C, Jagadheesan K, Verma AN. Caregiver's burden: A comparison between obsessive compulsive disorder and schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:337–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sukhodolsky DG, do Rosario-Campos MC, Scahill L, Katsovich L, Pauls DL, Peterson BS, et al. Adaptive, emotional, and family functioning of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1125–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moritz S, Hottenrott B, Randjbar S, Klinge R, Von Eckstaedt FV, Lincoln TM, et al. Perseveration and not strategic deficits underlie delayed alternation impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Psychiatry Res. 2009;170:66–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R. Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:783–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grover S, Dutt A. Perceived burden and quality of life of caregivers in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:416–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hertenstein E, Thiel N, Herbst N, Freyer T, Nissen C, Külz AK, et al. Quality of life changes following inpatient and outpatient treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A study with 12 months follow-up. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bobes J, González MP, Bascarán MT, Arango C, Sáiz PA, Bousoño M. Quality of life and disability in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16:239–45. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]