Abstract

It is known that transcription of kinB encoding a trigger for Bacillus subtilis sporulation is under repression by SinR, a master repressor of biofilm formation, and under positive stringent transcription control depending on the adenine species at the transcription initiation nucleotide (nt). Deletion and base substitution analyses of the kinB promoter (PkinB) region using lacZ fusions indicated that either a 5-nt deletion (Δ5, nt -61/-57, +1 is the transcription initiation nt) or the substitution of G at nt -45 with A (G-45A) relieved kinB repression. Thus, we found a pair of SinR-binding consensus sequences (GTTCTYT; Y is T or C) in an inverted orientation (SinR-1) between nt -57/-42, which is most likely a SinR-binding site for kinB repression. This relief from SinR repression likely requires SinI, an antagonist of SinR. Surprisingly, we found that SinR is essential for positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis indicated that SinR bound not only to SinR-1 but also to SinR-2 (nt -29/-8) consisting of another pair of SinR consensus sequences in a tandem repeat arrangement; the two sequences partially overlap the ‘-35’ and ‘-10’ regions of PkinB. Introduction of base substitutions (T-27C C-26T) in the upstream consensus sequence of SinR-2 affected positive stringent transcription control of PkinB, suggesting that SinR binding to SinR-2 likely causes this positive control. EMSA also implied that RNA polymerase and SinR are possibly bound together to SinR-2 to form a transcription initiation complex for kinB transcription. Thus, it was suggested in this work that derepression of kinB from SinR repression by SinI induced by Spo0A∼P and occurrence of SinR-dependent positive stringent transcription control of kinB might induce effective sporulation cooperatively, implying an intimate interplay by stringent response, sporulation, and biofilm formation.

Keywords: sporulation, biofilm formation, stringent transcription control, transcription initiation, SinR transcription regulator, RNA polymerase, decoyinine

Introduction

In Bacillus subtilis, entry into the sporulation pathway is governed by a member of the response regulator family of transcription factors known as Spo0A (Hoch, 1993). Spo0A is indirectly phosphorylated by a multicomponent phosphorelay system involving at least two kinases called KinA and KinB (Stephenson and Hoch, 2002). An increased level of phosphorylated Spo0A (Spo0A∼P) results in repression of abrB transcription (Strauch et al., 1990), leading to derepression of transcription of the σH (spo0H) gene encoding σH. kinA is transcribed by RNA polymerase (RNAP) possessing σH (Predich et al., 1992), but kinB is transcribed by RNAP possessing σA (Trach and Hoch, 1993; Dartois et al., 1996). Hence, kinB transcribed by σA-RNAP is supposed to be a trigger gene for sporulation rather than kinA.

Expression of the kinA and kinB genes is under positive stringent transcription control (Tojo et al., 2013). Their expression is induced upon amino acid starvation through GDP 3′-diphosphate (ppGpp) inhibition of GMP kinase (Kriel et al., 2012) or by the addition of decoyinine, a GMP synthase inhibitor (Mitani et al., 1977; Tojo et al., 2013), resulting in the reciprocal change of a GTP decrease and an ATP increase (Ochi et al., 1981; Tojo et al., 2010). The transcription initiation nucleotide (nt) of stringent promoters PkinA, PkinB and PilvB (Pilv-leu) under positive stringent transcription control is the adenine species; ilvB is the first gene of the ilv-leu operon for branched-chain amino acid synthesis (Krásný et al., 2008; Tojo et al., 2008, 2013). In contrast, the transcription initiation nt of stringent genes such as ptsG and pdhA for glucose catabolism under negative stringent transcription control is the guanine species (Tojo et al., 2010). It is likely that occurrence of both the positive and negative stringent transcription controls causes the B. subtilis cell to enter the sporulation phase (Fujita et al., 2012; Tojo et al., 2013).

The sinR gene was originally isolated as a sporulation inhibition (sin) gene in multiple copies (Gaur et al., 1986). SinR represses transcription from the Spo0A∼P-dependent promoters of sporulation genes such as spoIIA and spoIIG (Cervin et al., 1998). Moreover, transcription of kinB was found to be repressed by SinR on lacZ-fusion analysis (Dartois et al., 1996). Furthermore, the SinR repressor is the master regulator of the formation of a biofilm, a natural lifestyle for most bacteria formed on natural and artificial surfaces (Kearns et al., 2005; Stewart and Franklin, 2008). The wild-type B. subtilis secretes exopolysaccharides (EPSs) and proteins to form an extracellular matrix for building the biofilm (Stewart and Franklin, 2008; Vlamakis et al., 2013). The extracellular matrices are composed of EPSs synthesized from the gene products of the 15-gene epsA-O operon, TasA protein fibers, and the BslA surface layer protein (Vlamakis et al., 2013). SinR is one of the major regulators of the genes required for biofilm formation. SinR binds to the promoter regions of the epsA-O and tapA-sipW-tasA operons to repress their expression (Kearns et al., 2005; Chu et al., 2006). The consensus DNA binding sequence for SinR comprises a 7-bp pyrimidine-rich sequence (GTTCTYT, with Y representing an unspecified pyrimidine base), which can be found in an inverted and tandem repeat orientation/arrangement and in a monomer state at SinR operator sites (Kearns et al., 2005; Chu et al., 2006; Colledge et al., 2011). The direct interaction of amino acid residues of SinR with bases of its consensus sequences in an inverted repeat orientation was visualized in the crystal structure of the complex of SinR with operator DNA of the eps promoter (Newman et al., 2013). SlrR is a protein homologous to SinR. SlrR binding to SinR inhibits the DNA-binding activity of SinR, and slrR expression itself is repressed by SinR (Kobayashi, 2008; Chai et al., 2010). Thus, these proteins form a double-negative feedback loop. The SinR antagonist SinI determines which protein is dominant in this loop through protein–protein interaction with SinR (Bai et al., 1993; Chai et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2008). sinI expression is transcriptionally induced by Spo0A∼P (Shafikhani et al., 2002), which is a master regulator of sporulation (Chai et al., 2008; Lopez et al., 2009). It was recently reported that post-transcriptionally regulated heterogeneous expression of SinR is important for the differentiation of cells present in a biofilm (Ogura, 2016).

In this work, we identified a pair of SinR consensus sequences in an inverted orientation (SinR-1) between nt -57/-42 (+1 is transcription initiation nt) as a SinR-binding site for kinB repression. Unexpectedly, we found that SinR is essential for positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis indicated that SinR bound not only to SinR-1 but also to SinR-2 consisting of another pair of SinR consensus sequences in a tandem repeat arrangement (nt -29/-8) that partially overlap the ‘-35’ and ‘-10’ regions, respectively, which is likely involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Their Construction

The B. subtilis strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. To construct transcriptional promoter-lacZ fusion strains of kinB, PkinB regions comprising nt -75/+10, -75/+10 [with base substitution of A at nt +1 with G (A+1G)], -65/+10, -85/+10, -95/+10, -75/+10 [with 5-nt deletion (Δ5) (-61/-57)], -75/+10 [with 10-nt deletion (Δ10) (-64/-55)], and -75/+10 (with base substitution of G at -45 with A (G-45A) and Δ5] were amplified using the primer pairs of F75c/R10c1, F75c/R93, F90/R10c1, F92/R10c1, F82/R10c1, F95/R10c2, F96/R10c2, and F17/R17 (Supplementary Table S2-1), respectively, and DNA of strain 168 as a template. The PCR products were trimmed with XbaI and BamHI, and then ligated with the XbaI-BamHI arm of plasmid pCRE-test2 (Miwa and Fujita, 2001). The ligated DNAs were used for transformation of Escherichia coli strain DH5α to ampicillin-resistance (50 μg/ml) on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plates (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). The correct construction of the fusions in the resulting plasmids was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids carrying the PkinB regions with and without a base substitution and (or) deletion were linearized with PstI, and then used for double-crossover transformation of strain 168 to chloramphenicol-resistance (5 μg/ml) on tryptose blood agar base (Difco) with 10 mM glucose (TBABG) plates, which produced strains FU1191 PkinB (-75/+10), FU1193 PkinB (-75/+10 A+1G), FU1190 PkinB (-65/+10), FU1192 PkinB (-85/+10), FU1182 PkinB (-95/+10), FU1195 PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5), FU1196 PkinB (-75/+10 Δ10), and FU1217 PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A Δ5), respectively.

Table 1.

Bacillus subtilis strains used in this work.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | Anagnostopoulos and Spizizen, 1961 |

| FU1115 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ] | Tojo et al., 2013 |

| FU1116 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 A+1G)-lacZ] | Tojo et al., 2013 |

| FU1191 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1193 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 A+1G)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1190 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-65/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1192 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-85/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1182 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-95/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1195 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1196 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 Δ10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1204 | trpC2 ΔsinR::erm | This work |

| FU1206 | trpC2 ΔsinR::erm amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1210 | trpC2 ΔsinR::erm amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1216 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1217 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A Δ5)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1218 | trpC2 ΔsinR::erm amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1219 | trpC2 ΔsinR::erm amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A Δ5) -lacZ] | This work |

| FU1224 | trpC2 ΔsinR::erm amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10)Δ5-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1225 | trpC2 ΔsinI::spc | This work |

| FU1226 | trpC2 ΔslrR::tc | This work |

| FU1230 | trpC2 ΔsinI::spc amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1231 | trpC2 ΔslrR::tc amyE::[cat PkinB (-75/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1237 | trpC2 ΔsinI::spc amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1238 | trpC2 ΔslrR::tc amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1241 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 A-17G)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1242 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 G-16A)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1243 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 T-15C)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1244 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 G-14A)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1245 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 T-20C T-19C)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1246 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 T-18C A-17G)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1247 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 G-16A T-15C)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1248 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 C-26T T-25C)-lacZ] | This work |

| FU1249 | trpC2 amyE::[cat PkinB (-55/+10 T-27C C-26T)-lacZ] | This work |

| ASK2102 | trpC2 rpoC::pMUTinHis (Emr) sigB Δ2 (Cmr) sigH ΔHB (Kmr)sigW ΔHB (Spr) | Yano et al., 2011 |

To construct strains FU1216 PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A), FU1241 PkinB (-55/+10 A-17G), FU1242 PkinB (-55/+10 G-16A), FU1243 PkinB (-55/+10 T-15C), FU1244 PkinB (-55/+10 G-14A), FU1245 PkinB (-55/+10 T-20C T-19C), FU1246 PkinB (-55/+10 T-18C A-17G), FU1247 PkinB (-55/+10 G-16A T-15C), FU1248 PkinB (-55/+10 C-26T T-25C), and FU1249 PkinB (-55/+10 T-27C C-26T), the upstream and downstream parts of the PkinB region (nt -75/+10) and the PkinB region (nt -55/+10) were separately amplified with the respective two primer pairs F16a/R16b and F16c/R10c1, F55c/R41b and F41c/R10c3, F55c/R42b and F42c/R10c3, F55c/R43b and F43c/R10c3, F55c/R44b and F44c/R10c3, F55c/R45b and F45c/R10c3, F55c/R46b and F46c/R10c3, F55c/R47b and F47c/R10c3, F55c/R48b and F48c/R10c3, and F55c/R49b and F49c/R10c3 for FU1216, FU1241, FU1242, FU1243, FU1244, FU1245, FU1246, FU1247, FU1248, and FU1249 (Supplementary Table S2-1) using chromosomal DNA of strains 168 as a template for FU1216 and chromosomal DNA of strain FU1115 PkinB (-55/+10) as a template for FU1241 to FU1249. Next, the respective two PCR products were mixed, and extension reactions were carried out without any primer. PCR with the resultant fragment as a template and a primer pair (F16a/R10c1 for FU1216, or F55c/R10c3 for FU1241 to FU1249)(Supplementary Table S2-1) was performed to amplify the combined DNA fragment, which was then trimmed with XbaI and BamHI, and cloned into plasmid pCRE-test2 (Miwa and Fujita, 2001) in E. coli strain DH5α, and the constructed plasmids were used for transformation of strain 168, as described above, resulting in strains FU1216, and FU1241 to FU1249.

Strain FU1204 (ΔsinR::erm) was constructed as follows. The regions upstream and downstream of the sinR gene were firstly amplified by PCR using DNA of strain 168 as a template, and primer pairs F04a/F04b and F04e/F04f, respectively. The erm cassette was amplified by PCR using DNA of plasmid pMUTIN2 (Yoshida et al., 2000) as a template, and primer pair F04c/F04d. Secondly, recombinant PCR involving primer pair F04a/F04f and three PCR fragments resulted in a PCR product covering the region upstream of sinR, the erm gene, and the region downstream of sinR. The resultant recombinant PCR product was used to transform strain 168 to erythromycin-resistance (0.3 μg/ml) on TBABG plates to produce strain FU1204. Strains FU1206, FU1210, FU1218, FU1219, and FU1224, which carry ΔsinR::erm and each of the lacZ fusions, were obtained by transformation of FU1115, FU1191, FU1216, FU1217, and FU1195 with DNA of strain FU1204 to erythromycin-resistance, respectively.

Strains FU1225 (ΔsinI::spc) and FU1226 (ΔslrR::tc) were obtained by transformation of strain 168 with DNAs of strain NCIB3610 carrying ΔsinI::spc (Ogura, 2016) and strain 168 carrying ΔslrR::tc (Ogura et al., 2014) to resistance to spectinomycin (60 μg/ml) and tetracycline (10 μg/ml) on TBABG plates, respectively. Strains FU1230, FU1237, FU1231, and FU1238, which carry ΔsinI::spc or ΔslrR::tc, and each of the lacZ fusions, were obtained by transformation of strains FU1191, and FU1115 [PkinB (-55/+10)] with DNAs of strain FU1225 or FU1226.

Cell Cultivation and β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) Assaying

The lacZ-fusion strains were grown at 30°C overnight on TBABG plates containing the appropriate antibiotic(s); chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), erythromycin (0.3 μg/ml), spectinomycin (60 μg/ml), and (or) tetracycline (10 μg/ml). The cells were inoculated with an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in 50 ml of a nutrient sporulation medium (NSMP) (Fujita and Freese, 1981), and then cultivated. Then, 1 ml aliquots of the culture were withdrawn at 1-h intervals, and the β-Gal activity in crude cell extracts was measured spectrophotometrically, as described previously (Yoshida et al., 2000). The cells were also inoculated into 50 ml of a minimal sporulation medium containing 25 mM glucose and 50 μg/ml tryptophan (S6) (Fujita and Freese, 1981). (In the case of the inoculation of the ΔsinR, ΔsinI, and ΔslrR strains into S6 medium, the cells were first cultivated in LB medium before inoculation.) When the cells reached an OD600 of 0.5, 15 ml each culture was distributed into two flasks, and decoyinine was added to one flask to give a final concentration of 500 μg/ml (18 mM). Before and after decoyinine addition, 1-ml aliquots of the culture were withdrawn at 30-min intervals, and the β-Gal activity was measured.

Sporulation Percentage Measurement

The titers of viable cells (V) and spores (S) that were heat-resistant (75°C for 20 min), for the cultures of strains 168 and FU1204 (ΔsinR), were measured to obtain the sporulation percentages (S/V x 100) at T0 and T20 (0 and 20 h after entry into the stationary cell phase during sporulation in NSMP). The sporulation percentages for S6 cultures at 0 and 10 h after decoyinine addition (T0 and T10) were also measured.

Purification of SinR and RNAP

SinR was purified from E. coli RL4220, a BL21(DE3) derivative producing SinR (Kearns et al., 2005; Ogura et al., 2014), according to the method described previously, except for the use of a French pressure cell to prepare cell extracts (Chai et al., 2010). RNAP was purified from B. subtilis ASK2102 cells as described previously (Yano et al., 2011). The His tag was removed from His-SinR with biotinylated thrombin protease. SinR was dialyzed against dialysis buffer [10 mM Tris-Cl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 50% glycerol, pH 8.0]. His-RNAP was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, and 30% glycerol, pH 8.0. The proteins were stored at -20°C.

EMSA Analysis

The PCR primers and template DNA used for preparing biotinylated probes are shown in Supplementary Tables S1, S2-2. Site-directed mutagenesis of the probes was performed using an oligonucleotide-based PCR method as described previously (Ogura and Tanaka, 1996). For EMSA, appropriate amounts of SinR and (or) RNAP were incubated for 15 min at 28°C with a probe (20 fmol) in 16 μl of a reaction mixture (15 mM Tris-Cl, 4 mM MOPS-KOH, 15 mM KCl, 50 mM NaCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM DTT, and 12.5% glycerol, pH 7.8) containing 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) (GE Healthcare). After the addition of 2 μl of loading buffer [40% glycerol, 1× TBE (89 mM Tris-borate, and 2 mM EDTA, pH 8), 2 μg/ml bromophenol blue], the samples were applied onto a polyacrylamide gel, and electrophoresis was performed in 0.1× TBE buffer at 4°C. The method used for the detection of biotin-labeled DNA was described previously (Ogura and Tanaka, 1996).

Most EMSAs were performed with the gradient of the SinR concentration. Not a few critical EMSAs were duplicated.

Results

kinB Transcription and Its Regulation

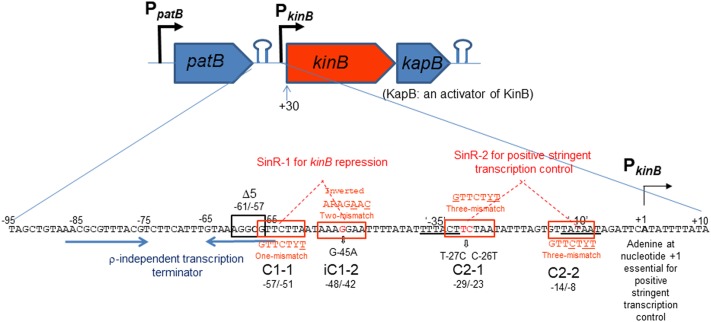

The kinB gene encoding one of the two major sensor kinases (KinA and KinB) of the phosphorelay system that phosphorylates Spo0A was identified, and its transcription was examined (Trach and Hoch, 1993). The kinB gene is transcribed from the σA-dependent promoter, which starts from adenine (nt +1) (Trach and Hoch, 1993) (Figure 1). It is co-transcribed with kapB encoding a lipoprotein involved in autophosphorylation of KinB and phosphorylation of Spo0F (Dartois et al., 1997). An ρ-independent transcription terminator was found downstream of kapB, which presumably results in the kinB-kapB transcript. The patB-encoding aminotransferase is located immediately upstream of kinB. Another ρ-independent transcription terminator was found downstream of the patB gene, suggesting that the read-through of patB transcription is blocked. It was communicated in SubtiWiki 2.01 (Michna et al., 2016) that the efficient blockage at the transcription terminator actually occurred. kinB transcription was reported to be repressed by SinR (Dartois et al., 1996). It was reported to be presumably repressed by AbrB (Strauch, 1995) and CodY (Molle et al., 2003). Recently, kinB expression was found to be under positive stringent transcription control (Tojo et al., 2013), that is, it is positively regulated upon stringent conditions such as amino acid starvation or on the addition of decoyinine, an inhibitor of GMP synthase, which induces stringent transcription control as well as sporulation. The positive stringent transcription control is strictly dependent on the adenine species at the transcription initiation nt, as described for kinB transcription (Tojo et al., 2013). However, kinB expression was not regulated by CodY or AbrB, at least as observed when examined by use of an lacZ fusion with the PkinB region (nt -55/+10)(Tojo et al., 2013). To determine if the CodY- or AbrB-binding site is located outside of this region, we attempted to fuse a larger PkinB region with lacZ to yield the largest PkinB -lacZ fusion carrying PkinB (nt -95/+120); the larger fragment including the patB gene upstream of kinB could not be cloned to plasmid pCRE-test2, presumably because patB is harmful in its multiple copy state in E. coli. No significant difference in lacZ expression by the largest lacZ-fusion strain was observed in the wild-type, ΔcodY, and ΔabrB genetic backgrounds, on cultivation in NSMP or S6 medium with and without decoyinine (data not shown), suggesting that the CodY- and AbrB-binding sites that affect PkinB are unlikely to be located in the PkinB region (nt -95/+120). This finding implied that kinB expression might not be directly regulated by AbrB and CodY.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the patB-kinB-kapB region of B. subtilis. Promoters (PpatB and PkinB) and two stem-loop structures are shown. The kinB gene is cotranscribed with the kapB gene encoding an activator of KinB. This kinB-kapB transcription terminates at the stem-loop structure (ρ-independent terminator) downstream of kapB. patB transcription from PpatB terminates at the stem-loop structure downstream of patB, which is indicated by two blue horizontal arrows. SinR-binding site 1 (SinR-1) consisting a pair of SinR consensus sequences (GTTCTYT) in an inverted orientation (C1-1, nt –57/–51 and iC1-2, nt –48/–42, boxed in red), which carries one mismatch and two mismatches to the consensus sequence (the mismatched nt are underlined), respectively. SinR-1 is involved in kinB repression. The Δ5 deletion (boxed in black, nt –61/–57) and G-45A substitution suppressed the repression. The ‘–35’ and ‘–10’ regions of PkinB are doubly underlined. SinR-binding site 2 (SinR-2) consisting of a pair of SinR consensus sequences in a tandem orientation (C2-1, nt –29/–23 and C2-2, nt –14/–8), both carrying three-mismatches to the consensus sequence. The T-27C C-26T substitution partially affected positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. SinR-2 is likely involved in positive stringent transcription control. The adenine species at transcription initiation nt (+1) is required for positive stringent transcription control to occur (Krásný et al., 2008; Tojo et al., 2010, 2013).

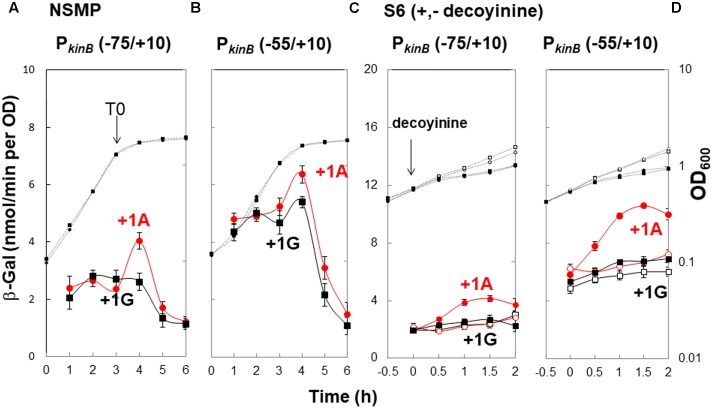

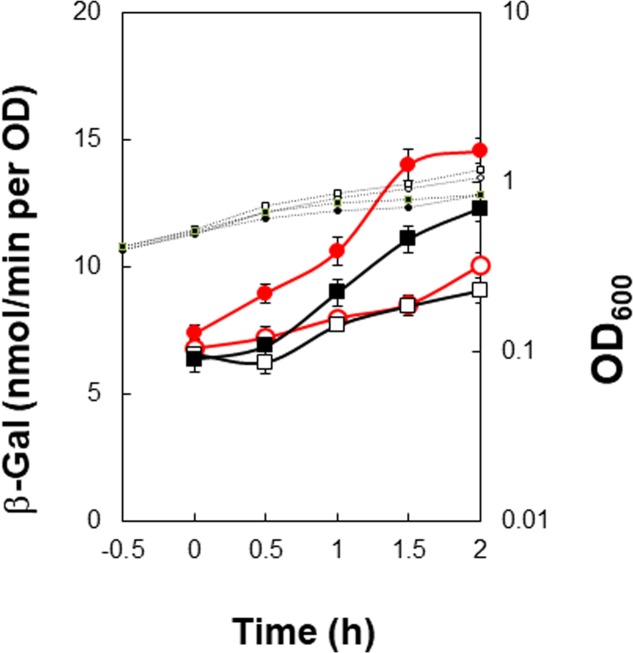

To confirm that positive stringent transcription control of PkinB during sporulation in nutrient NSMP medium and upon decoyinine addition in minimal S6 medium is dependent on the adenine species at the transcription initiation nt, we constructed lacZ fusion strains with the PkinB region (nt -75/+10) carrying adenine and guanine at the transcription initiation nt, and β-Gal synthesis was monitored during sporulation of the constructed strains, PkinB (-75/+10) and PkinB (-75/+10 A+1G), together with the previously constructed strains, PkinB (-55/+10) and PkinB (-55/+10 A+1G) (Tojo et al., 2013) (Figure 2). The positive stringent transcription control was clearly observed in strains PkinB (-75/+10) and PkinB (-55/+10) for both sporulation in NSMP medium and decoyinine-induced sporulation in S6 medium, that is, some enhancement around T0.5 for sporulation in NSMP, and roughly a 1.5-fold increase after decoyinine addition, respectively (Figure 2). But, this positive control was not observed for strains PkinB (-75/+10 A+1G) and PkinB (-55/+10 A+1G). These results clearly confirmed that positive stringent transcription of PkinB depends on the adenine species at the transcription initiation nt (+1). Furthermore, the basal level of β-Gal synthesis was somewhat repressed in strains PkinB (-75/+10) and PkinB (-75/+10 A+1G) in comparison with that in strains PkinB (-55/+10) and PkinB (-55/+10 A+1G) for both sporulation in NSMP medium and decoyinine–induced sporulation in S6 medium (Figure 2), implying that the PkinB region (nt -75/-55) might possess a binding site or part of one for a transcription repressor.

FIGURE 2.

Requirement of the adenine species at the transcription initiation base for positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. The PkinB regions of nt –75/+10 and –55/+10 were fused with lacZ to yield strains FU1191 PkinB (–75/+10) and FU1115 PkinB (–55/+10). The adenine at nt +1 was replaced with a guanine to yield strains FU1193 PkinB (–75/+10 A+1G) and FU1116 PkinB (–55/+10 A+1G). The synthesis of β-Gal encoded by lacZ in strains FU1191 and FU1115, and strains FU1193 and FU1116 was monitored during sporulation in a nutrient sporulation medium, NSMP (A,B), and after addition of decoyinine to the culture in minimal medium, S6 (C,D). Circles and squares indicate the PkinB with adenine and guanine at nt +1, respectively. β-Gal synthesis during sporulation in NSMP was indicated by closed symbols. In the case of S6 medium, closed and open symbols indicate with and without addition of decoyinine, respectively. Large and small symbols denote β-Gal activity and OD600, respectively. In all Figures of β-Gal monitoring, the standard deviations of the average β-Gal activity values from the multiple replicates are indicated by error bars (one experiment gives two activity values at an indicated time); tiny error bars are invisible due to their overlap with the symbols. In the case of β-Gal monitoring shown in (A,B), the experiments were performed with triple replicates.

In addition, it was notable that the positive stringent transcription control only partially contributed to enhancement of kinB transcription for sporulation in NSMP in contrast to a large contribution to it for decoyinine-induced sporulation in S6.

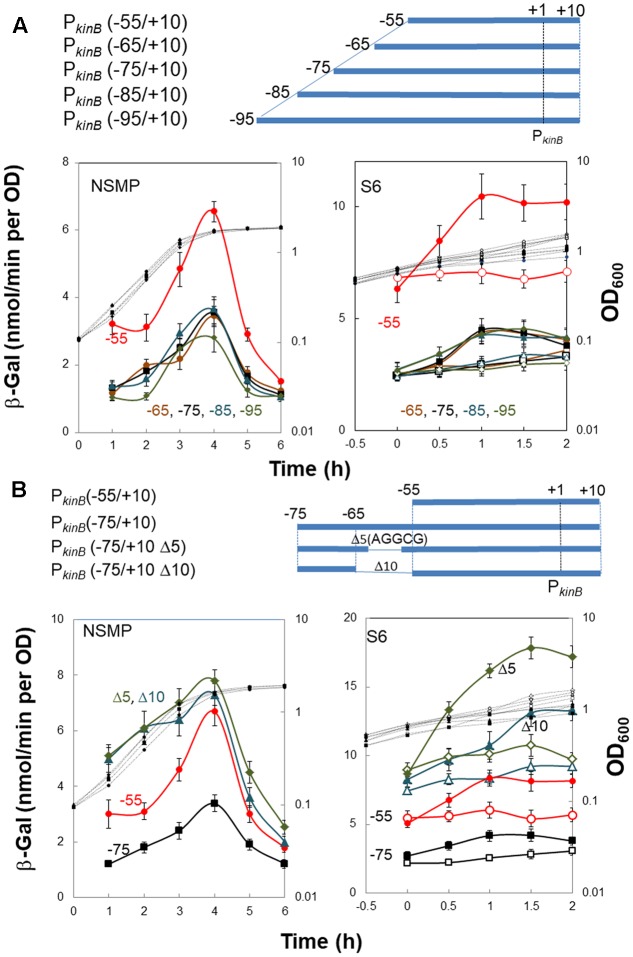

Truncation and Deletion Analysis of the PkinB Region to Identify a Repressor-Binding Site

To localize a repressor-binding site in the PkinB region (nt -95/-55), we constructed a successive series of lacZ-fused PkinB truncation derivatives [PkinB (-95/+10), PkinB (-85/+10), PkinB (-75/+10), PkinB (-65/+10), and PkinB (-55/+10)]. When β-Gal synthesis in these truncation derivatives was monitored during sporulation in NSMP (Figure 3A, left), the PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ derivative exhibited a higher level of β-Gal synthesis than the other truncation derivatives [PkinB (-95/+10), PkinB (-85/+10), PkinB (-75/+10), and PkinB (-65/+10)], which showed similar levels. When it was monitored upon decoyinine addition to the S6 cultures (Figure 3A, right), the basal level of β-Gal synthesis by the PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ derivative before decoyinine addition was higher in comparison with those by the other derivatives. However, the positive stringent transcription control of PkinB was observed to be nearly the same level, approx.1.5-fold increase, for all the truncation derivatives, suggesting that the relief from kinB repression is not involved in this positive stringent transcription control. These overall results suggest that a binding site of a repressor or part of it is likely located in the PkinB region (nt -65/-55), which is responsible for kinB repression but not involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB.

FIGURE 3.

Truncation and deletion analyses of the PkinB region to identify a repressor-binding site. (A) Truncation analysis. β-Gal synthesis in strains FU1115 PkinB (–55/+10) (red circles), FU1190 PkinB (–65/+10) (brown circles), FU 1191 PkinB (–75/+10) (squares), FU1192 PkinB (–85/+10) (triangles), and FU1182 PkinB (–95/+10) (diamonds) was monitored during sporulation in NSMP medium and after addition of decoyinine to S6 medium. (B) Inner deletion analysis. β-Gal synthesis in strains FU1115 PkinB (–55/+10) (circles), FU 1191 PkinB (–75/+10) (squares), FU1195 PkinB (–75/+10 Δ5)(triangles), and FU1196 PkinB (–75/+10 Δ10) (diamonds) was monitored during sporulation in NSMP medium and after addition of decoyinine to S6 medium.

Next, we introduced inner deletions [Δ10 (10-nt deletion, nt -64/-55) and Δ5 (5-nt deletion, nt -61/-57)] into the PkinB (-75/+10) region to confirm that the repressor-binding site is located between nt -65/-55. When β-Gal synthesis by the derivatives carrying each of the inner deletions [PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5) and PkinB (-75/+10 Δ10) was monitored together with that by strains carrying no inner deletion, PkinB (-75/+10) and PkinB (-55/+10) (Figure 3B), the inner deletion derivatives exhibited higher levels of β-Gal synthesis than that by the derivative without them [PkinB (-75/+10)] for sporulation in NSMP (Figure 3B, left) and in decoyinine-induced sporulation (Figure 3B, right). Moreover, the higher levels of β-Gal synthesis by these derivatives were in the order of PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5), PkinB (-75/+10 Δ10), PkinB (-55/+10), and PkinB (-75/+10). The differences could be attributed to newly created sequence variation of nt -65/-55 in these deletion derivatives, which might affect the binding of the assumed kinB repressor. However, nearly the same level of positive stringent transcription control was observed for these derivatives (Figure 3B, right). The overall deletion analysis (Figure 3) indicated that the inner deletion of Δ5 (AGGCG, nt -61/-57) disrupted a binding site or part of it for the assumed repressor for kinB transcription, which is not involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB.

Identification of a Putative Binding Site of SinR for kinB Repression, and Involvement of SinR in Positive Stringent Transcription Control of PkinB

The sinR gene was isolated as a sporulation inhibition gene in multiple copies (Gaur et al., 1986). At first, we determined the sporulation percentages (%) during cultivation in NSMP medium and during cultivation in S6 after decoyinine addition. The sporulation percentages for strains 168 and FU1204 (ΔsinR) in NSMP were < 5 × 10-5% at T0, and 80 and 100% at T20, respectively. The sporulation percentages for strains 168 and FU1204 in decoyinine-induced sporulation were 0.4% and 1.5% at T0 (at decoyinine addition time) and 40% and 98% at T10. (The sporulation experiments were repeated at least three times. Representative values were presented. The standard deviations were less than 15% of the values shown.) Hence, the ΔsinR deletion tended to promote the sporulation, especially on cultivation in S6 medium with decoyinine.

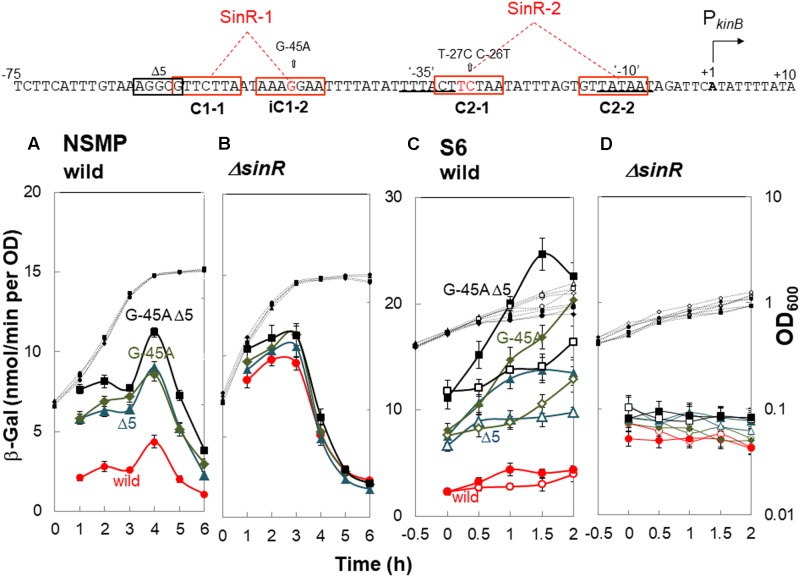

A previous study involving a lacZ-fusion with the PkinB region (Dartois et al., 1996) suggested that kinB expression is repressed by SinR, and the substitution of guanine at nt -45 in the PkinB region with adenine resulted in relief from SinR repression. Thus, we constructed four strains each carrying PkinB (-75/+10), PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5), PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A), and PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5 G-45A), in the wild-type (sinR+) and ΔsinR genetic backgrounds. In the sinR+ strains cultivated in NSMP medium, the introduction of the inner deletion of Δ5 or the base substitution (G-45A) greatly and equally relieved the severe repression of lacZ expression observed in strain [PkinB (-75/+10)] without the deletion or substitution (Figure 4A). Moreover, the introduction of both Δ5 and G-45A gave further relief from the repression. In the ΔsinR strains cultivated in NSMP, the severe repression of the strain without Δ5 and G-45A as well as the residual repression observed in the Δ5 or G-45A strain were well relieved on the introduction of ΔsinR (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

In vivo identification of SinR-1 for kinB repression by SinR. (Top) The nt sequence of the PkinB region (nt -75/+10) is shown, SinR-1 and SinR-2 being indicated. (A,C) β-Gal synthesis by strains FU1191 PkinB (-75/+10) (circles), FU1195 PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5) (triangles), FU1216 (PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A) (diamonds), and FU1217 PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5 G-45A) (squares) in the wild-type genetic background was monitored during sporulation in NSMP medium and after addition of decoyinine to S6 medium. (B,D) β-Gal synthesis by strains FU1210 [PkinB (-75/+10) ΔsinR] (circles), FU1224 [PkinB (–75/+10 Δ5) ΔsinR] (triangles), FU1218 [PkinB (-75/+10 G-45A) ΔsinR] (diamonds), and FU1219 [PkinB (-75/+10 Δ5 G-45A) ΔsinR] (squares) in the ΔsinR background was monitored during sporulation in NSMP medium and after addition of decoyinine to S6 medium.

For decoyinine-induced sporulation of the sinR+ background strains in S6 medium, Δ5 or G-45A equally well relieved the severe repression in strain PkinB (-75/+10) carrying no deletion or base substitution (Figure 4C). Also, it was completely relieved in strain PkinB (-75/+10) carrying both Δ5 and G-45A. In ΔsinR strains cultivated in S6 (Figure 4D), the levels of lacZ expression before decoyinine addition were nearly the same in strains PkinB (-75/+10) with and without Δ5 and (or) G-45A, indicating that the repression observed in strain PkinB (-75/+10) was well relieved on the introduction of ΔsinR. Surprisingly, positive stringent transcription control of PkinB, which is inducible through the addition of decoyinine, did not occur in any ΔsinR strain with and without Δ5 and (or) G-45A at all (Figure 4D). However, significant repression of lacZ expression was remained even in the genetic background of ΔsinR, as observed in Figure 4D as well as in Figure 4B. These results indicated that SinR is involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB.

A mild plateau of β-Gal synthesis around T0 and a clear decrease in it after T1 were observed in all ΔsinR strains for sporulation in NSMP (Figure 4B). We could not explain this sporulation phase-dependent variation of β-Gal synthesis without SinR regulation, because SinR repression of kinB transcription and positive stringent transcription control of PkinB did not occur in the ΔsinR strains during sporulation under the cultivation conditions (Figures 4B,D).

The consensus DNA binding sequence for SinR comprises a sequence (GTTCTYT) that can be found in inverted and tandem repeat arrangement/orientation and in a monomer state at SinR operator sites (Kearns et al., 2005; Chu et al., 2006; Colledge et al., 2011). Examination of the PkinB sequence around the Δ5 deletion and the G-45A substitution allowed us to identify a pair of SinR consensus sequences [C1-1 (nt -57/-51) and iC1-2 (-48/-42)] in an inverted repeat orientation (SinR-1 site), each consensus unit containing part of the Δ5 deletion or the G-45A substitution [Figures 1, 4 (Top)]. Therefore, SinR-1 is most likely a SinR-binding site for kinB repression.

As described above, SinR is essential for positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. Examination of the sequences around the ‘-35’ and ‘-10’ regions revealed another pair of SinR consensus sequences [C2-1 (nt -29/-23) and C2-2 (-14/-8)] in a tandem repeat arrangement (SinR-2 site)[Figures 1, 4 (Top)]. The C2-1 and C2-2 sequences partially overlap the ‘-10’ and ‘-35’ regions of PkinB, which might be possibly a SinR-binding site for positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. We attempted to isolate mutants of strain FU1115 [PkinB (-55/+10)-lacZ] that are defective in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. We arbitrarily introduced nine base substitutions to the SinR-2 sequence (nt -29/-8) in the PkinB (-55/+10) region [A-17G, G-16A, T-15C, G-14A, (T-20C T-19C), (T-18C A-17G), (G-16A T-15C), (C-26T T-25C), and (C-26T T-27C)], and examined if the strength of each mutant PkinB is comparable to that of the wild-type, and if β–Gal synthesis under the control of the mutant PkinB is positively regulated after decoyinine addition. Thus, we found that only one mutant, FU1249 PkinB (-55/+10 C-26T T-27C) carrying the substitution in the C2-1 consensus sequence of SinR-2, synthesized β-Gal almost at the same level as wild-type strain FU1115, and exhibited partially impaired positive stringent transcription control in comparison with strain FU1115 (Figure 5). Although the other eight substitutions affected the PkinB strength, they did not affect positive stringent transcription control significantly (Supplementary Figure S1). The T-15C, G-14A, and (G-16A T-15C) mutations abolished the PkinB activity. The A-17G, (T-20C T-19), and (T-18C A-17G) mutations decreased it by several-fold, but did not affect positive stringent transcription control. The G-16A and (C-26T T-25C) mutations considerably enhanced the PkinB activity, but they did not affect positive stringent transcription control significantly. These results suggested that the C2-1 consensus sequence of SinR-2, where the C-26T T-27C substitution only affecting positive stringent transcription control of PkinB is located, is likely involved in its positive stringent transcription control.

FIGURE 5.

Partial decrease of positive stringent transcription control of PkinB induced by base substitutions (T-27C C-26T). β-Gal synthesis by strains FU1115 PkinB (–55/+10) (circles), and FU1249 PkinB (–55/+10 T-27C C-26T) (squares) was monitored after addition of decoyinine to S6 medium. The β-Gal monitoring was performed with quadruple replicates.

Examination of the Effects of ΔsinR, ΔslrR, and ΔsinI on kinB Repression and Positive Stringent Transcription Control of PkinB

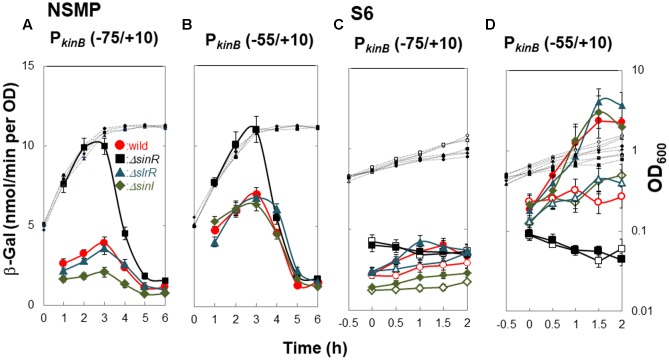

ΔsinR relieved the repression of kinB transcription involving SinR-1, as described above (Figure 4). It also abolished positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. Thus, we examined the effects of SlrR (Kobayashi, 2008), a paralog of SinR, and SinI (Bai et al., 1993), an antagonist of SinR, on kinB repression and positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. We constructed lacZ-fusion strains PkinB (-75/+10) carrying ΔslrR or ΔsinI, and PkinB (-55/+10) carrying ΔsinR, ΔslrR or ΔsinI. As shown in Figure 6A, β-Gal synthesis by strain [PkinB (-75/+10) ΔsinR] was largely relieved from the repression in the wild-type strain PkinB (-75/+10) in sporulation in NSMP medium. ΔslrR did not relieve the repression, but ΔsinI further strengthened it. Thus, kinB repression by SinR seemed hard to be relieved in the absence of SinI. Moreover, ΔsinR also relieved mild repression by SinR which resulted from partial deletion of the C1-1 sequence in PkinB (-55/+10) (Figure 6B). Neither ΔslrR nor ΔsinI affected this mild repression.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of ΔsinR, ΔslrR, and ΔsinI on β-Gal synthesis under the control of PkinB. (A,C) β-Gal synthesis by strains FU1191 PkinB (–75/+10)(circles), FU1210 [PkinB (–75/+10) ΔsinR] (squares), FU1231 [PkinB (–75/+10) ΔslrR] (triangles), and FU1230 [PkinB (–75/+10) ΔsinI] (diamonds) was monitored during sporulation in NSMP medium and after the addition of decoyinine to S6 medium. (B,D) β-Gal synthesis by strains FU1115 PkinB (–55/+10)(circles), FU1206 [PkinB (–55/+10) ΔsinR] (squares), FU1238 [PkinB (–55/+10) ΔslrR] (triangles), and FU1237 [PkinB (–55/+10) ΔsinI] (diamonds) was monitored similarly.

Strains [PkinB (-75/+10) ΔsinR] and [PkinB (-55/+10) ΔsinR] exhibited neither the repression nor positive stringent transcription control of PkinB on decoyinine-induced sporulation in S6 (Figures 6C,D). Strain [PkinB (-75/+10) ΔslrR] exhibited no significant difference in either the repression or positive stringent transcription control in comparison to wild-type strain PkinB (-75/+10) (Figure 6C). ΔsinI did not affect positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. But, lacZ expression in strain [PkinB (-75/+10) ΔsinI] was most severely repressed, that is, this strain exhibited the lowest level of β-Gal synthesis before decoyinine addition (Figure 6C). On the other hand, the lacZ fusion strains [PkinB (-55/+10) ΔsinI] and [PkinB (-55/+10) ΔslrR] exhibited almost the same level of the repression and positive stringent transcription control of PkinB as the wild-type strain PkinB (-55/+10) (∼1.5-fold increase) (Figure 6D). The overall results indicated that SinI deficiency causes stronger SinR-dependent repression and reduces derepression, but SlrR is not involved in the repression, and also indicated that SinR is involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB, but SinI and SlrR are not.

EMSA Analysis of SinR Binding with Probes Carrying Deletion and Base-Substitution That Affect kinB Regulation in Vivo

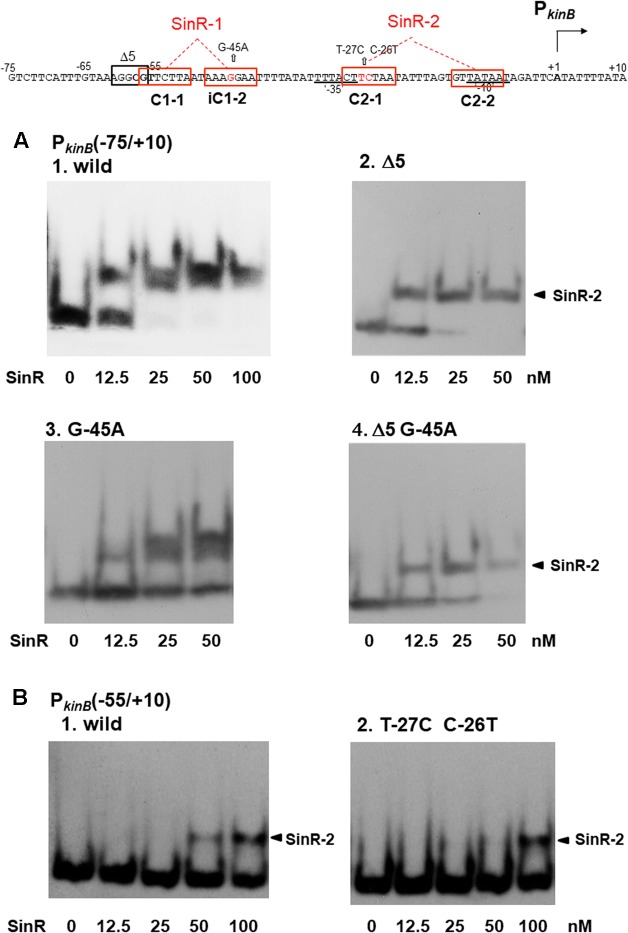

On lacZ fusion analysis using ΔsinR as well as Δ5, G-45A, and C-26T T-27C, SinR was found to be responsible not only for kinB repression involving SinR-1 consisting of C1-1 and iC1-2 (Figure 4), but also for positive stringent transcription control of PkinB probably involving SinR-2 consisting of C2-1 and C2-2 (Figures 4, 5). On EMSA analysis using the probes carrying Δ5 and G-45A, and C-26T T-27C, we found that these mutations actually affected in vitro SinR binding to SinR-1 and to SinR-2, respectively, as follows (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis of SinR binding to the PkinB region carrying deletion or base substitutions that affect β-Gal synthesis on lacZ-fusion analysis. (Top) The nt sequence of the PkinB region (nt –75/+10) is shown, SinR-1 and SinR-2 being indicated. (A) [1] EMSA results for SinR-binding to the PkinB (–75/+10) probe in a 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Increasing amounts of SinR (0, 12.5, 25, 50 nM) were used. (nM was calculated as the SinR monomer.) Upper and lower bands resulting from SinR-binding to the probe appeared. [2,3,4] EMSA results using the PkinB (–75/+10) probe carrying the Δ5 deletion, the G-45A base substitution, and Δ5 and G-45A, respectively. Hence, these mutant probes carry only an intact SinR-2. The arrowheads [2,4] indicate the position of the shifted band resulting from SinR binding to SinR-2. (B) EMSA results with the PkinB (-55/+10) probe carrying only SinR-2 consisting of C2-1 and C2-2. [1] EMSA results using the PkinB (–55/+10) probe (wild-type). [2] EMSA results using the PkinB (–55/+10) probe carrying the T-27C C-26T substitution in the C2-1 consensus sequence. DNA probes were prepared by use of primer pair and template DNA listed in Supplementary Tables S1, S2-2.

As shown in Figure 7A-1, the wild-type PkinB (-75/+10) probe gave the two closely located bands on EMSA, which likely resulted from SinR binding to SinR-1 and SinR-2. The upper band is invisible at 12.5 nM SinR, and visible at 25 nM with the PkinB (-75/+10) probe carrying the G-45A substitution, likely resulting from approximately 2-fold less binding affinity to SinR-1 (Figure 7A-3). This band disappeared with the probe carrying the Δ5 deletion or Δ5 and G-45A (Figures 7A-2,-4), suggesting that SinR cannot bind to SinR-1 if part of the C1-1 sequence is deleted by Δ5.

As described above, Figure 4C shows that in the wild-type cells with PkinB (-75/+10) during cultivation in S6 medium, as well as in those with PkinB (-75/+10) possessing Δ5 (and G-45A), approximately 1.5-fold positive stringent transcription control of PkinB steadily occurred, regardless of the level of kinB repression before decoyinine addition. The same level of positive stringent transcription control was also observed in the cells of a series of truncation and deletion derivatives of the PkinB region (nt -95/+10 to -55/+10) that exhibited different levels of kinB repression (Figure 3). These results suggested that SinR simultaneously binds to both SinR-1 and SinR-2 to form a larger complex than that on SinR binding to SinR-1 or SinR-2. Nevertheless, a more slowly migrating band other than the two closely located bands did not exist (Figure 7A). Thus, the closely located upper and lower bands were considered to probably result from simultaneous SinR binding to SinR-1 and -2, and from SinR binding to SinR-1 or SinR-2, respectively.

The C-26T T-27C substitution located in C2-1 partially affected the positive stringent transcription control (Figure 5). EMSA with the probe of PkinB (-55/+10) deleting part of C1-1 of SinR-1 gave only a shifted band most likely resulting from SinR binding to SinR-2 (Figure 7B). SinR binding affinity to SinR-2 with the probe carrying the C-26T T-27C substitution (Figure 7B-2) was significantly less than that of the wild-type PkinB (-55/+10) (Figure 7B-1).

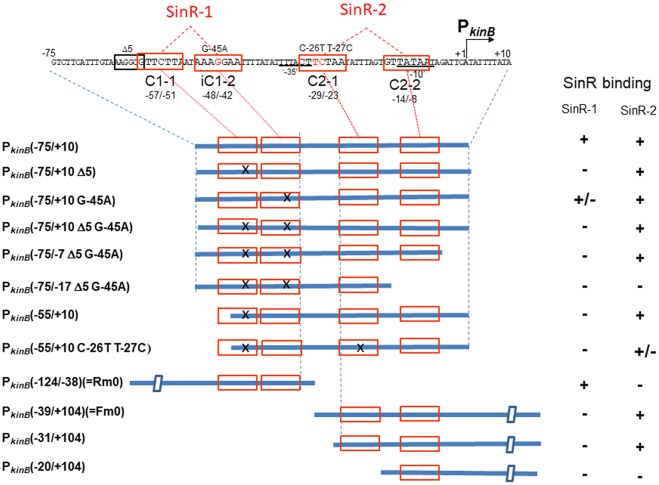

EMSA Analysis for SinR Binding to SinR-1 and SinR-2 Using Deleted and Mutated Probes

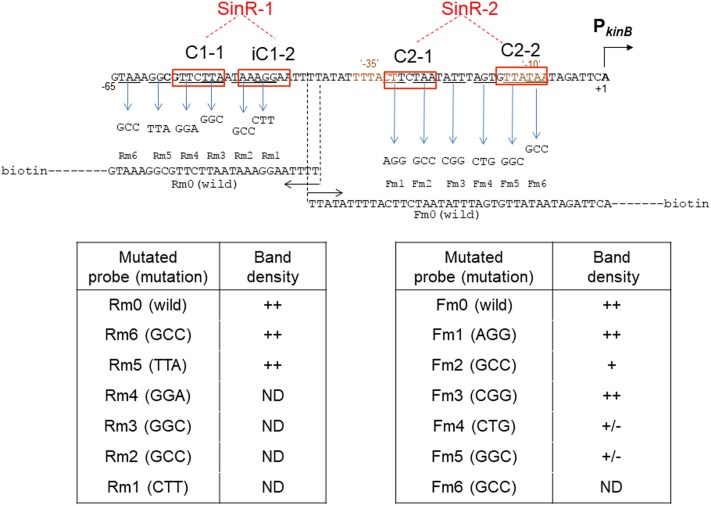

Figure 8 shows the arrangement of SinR-binding sites (SinR-1 and SinR-2), and illustrates the covering of the PkinB region by various probes for EMSA. The SinR binding ability to SinR-1 and (or) SinR-2 of the probes (+, +/- or -) is given in the right columns. SinR bound to SinR-1 and SinR-2 of the PkinB (-75/+10) probe, but it did not bind to SinR-1 of its mutant derivatives (Figure 7A). SinR bound to SinR-2 of the PkinB (-55/+10) probe, but it only partially bound to its mutant derivative (Figure 7B). SinR bound to SinR-1 of PkinB (-124/–38) (Rm0) and SinR-2 of PkinB-39/+104) (Fm0) (Supplementary Figure S3). It is particularly notable that the EMSA results that SinR bound to the PkinB (-75/-7 Δ5 G-45A) probe but not to the PkinB (-75/-17 Δ5 G-45A) probe (Supplementary Figures S2-1,-2) indicated that C2-2 is essential for SinR binding to SinR-2. (The migration rate of the very faint band observed in Supplementary Figure S2-2 was nearly half of that observed in Supplementary Figure S2-1, which might have resulted from binding of the SinR monomer to C1-1.) Moreover, the EMSA results that SinR bound to the PkinB (-31/+104) probe but not to the PkinB (-20/+104) probe (Supplementary Figures S2-3,-4) indicated that C2-1 is indispensable for SinR binding to SinR-2. (A very faint band observed in Supplementary Figure S2-4 is unknown.) These EMSA results involving deleted and base-substituted probes (Figure 8) allowed us to conclude that both C1-1 and iC1-2 of SinR-1 are necessary for SinR binding to SinR-1, whereas both C2-1 and C2-2 are necessary for SinR binding to SinR-2.

FIGURE 8.

Deletion analysis to localize SinR-binding sites (SinR-1 and SinR-2) by EMSA. (Top) The nt sequence of the PkinB region (nt –75/+10), where SinR-1 (C1-1 and iC1-2) and SinR-2 (C2-1 and C2-2) are localized, is shown. The EMSA probes cover various PkinB regions indicated by thick blue bars where SinR consensus sequences (red boxes) are shown; X means a defective consensus sequence.

It should be noted that EMSA analyses involving the probes of PkinB (-75/+10) and PkinB (-75/-7) carrying Δ5 G-45A gave an apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of approximately 10 nM for SinR binding to SinR-2 (Figure 7A and Supplementary Figure S2-1), but EMSA involving PkinB (-55/+10), PkinB (-31/+104), and PkinB (-39/+104) (Fm0) probes gave Kd of more than 100 nM for SinR binding to SinR-2 (Figure 7B-1 and Supplementary Figure S3-2). This finding implies that an unidentified sequence upstream of nt -55 might function to enhance SinR binding to SinR-2 without its binding to SinR-1. This unknown enhancement of SinR binding to SinR-2 remains to be studied.

Figure 9 summarizes the results of EMSA analyses involving a series of three-base substituted PCR probes to determine which parts of SinR-1 and SinR-2 sequences are necessary for SinR binding. For EMSA to determine which part of the SinR-1 is necessary for SinR binding, the mutant probes (Rm6, Rm5, Rm4, Rm3, Rm2, and Rm1) and the wild-type one (Rm0) were used, as illustrated on the left side of Figure 9. The EMSA results as to Rm0 and Rm1 to Rm6 are shown in the upper panel of Supplementary Figure S3-1. The relative densities of the shifted bands of the mutant probes [++, +, +/-, and ND (not detected)] to that of the wild-type (++) as to their binding to SinR-1 are arbitrary given in the lower left column from their vision (Supplementary Figure S3-1). The base-substitutions within C1-1 and iC1-2 of SinR-1 (Rm4, Rm3, Rm2, and Rm1) almost completely abolished the shifted band, whereas those upstream of C1-1 (Rm6 and Rm5) did not diminish the band density. The results indicated that both C1-1 and iC1-2 are essential for SinR-binding to SinR-1.

FIGURE 9.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis of SinR binding to the mutant PkinB probes. The wild-type probes [PkinB (–124/–38) ( = Rm0) and PkinB (–39/+104) ( = Fm0)], as well as the mutant ones carrying the respective three-base substitutions in the SinR-1 site (Rm1, Rm2, Rm3, Rm4, Rm5, and Rm6) and in the SinR-2 site (Fm1, Fm2, Fm3, Fm4, Fm5, and Fm6) were prepared using the wild-type and mutant primer pairs and a DNA template (Supplementary Tables S1, S2-2).

For EMSA of SinR binding to SinR-2, the mutant probes (Fm1, Fm2, Fm3, Fm4, Fm5, and Fm6) and the wild-type one (Fm0) were used, as illustrated on the right side of Figure 9. The EMSA data as to Fm0 and Fm1 to Fm6 are shown in the upper panel of Supplementary Figure S3-2. The relative band densities of the shifted bands of the mutant probes to that of the wild-type as to their binding to SinR-1 [++, +, +/-, and ND] are given in the lower right column. The base-substitutions in C2-1 (Fm2) only partially affected SinR binding to SinR-2, but those in C2-2 (Fm5) considerably affected it. Besides, the substitution (Fm4) immediately upstream of C2-2 partially affected it.

EMSA analysis with the mutant probes (Figure 9) indicated that SinR-binding to SinR-2 only partially requires C2-1 but it well requires C2-2. The EMSA results with deleted probes as described above (Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure S2) suggested that both C2-1and C2-2 are likely essential for SinR binding to SinR-2. This inconsistency might reflect the difference between the three-base substitution in C-2-1 (Figure 9) and its complete elimination (Figure 8). However, the role of AGT just upstream of C2-2 in SinR binding to SinR-2 is unknown. These EMSA results suggested that both C2-1 and C2-2 are likely necessary for SinR binding to SinR-2, although C2-1 might not be so strictly required in comparison with C2-2. Thus, the SinR binding site (SinR-2) likely comprises the two SinR consensus of C2-1 and C2-2 sequences in a tandem arrangement, which partially overlap the ‘-35’ and ‘-10’ regions of PkinB, respectively.

Lastly, the EMSA data (Supplementary Figures S3-1,-2, upper panels) as to the wild-type and mutant probes (Rm0, Rm2, Rm4, Rm5, Fm0, and Fm5) were confirmed by EMSA with the gradient of the SinR concentration (Supplementary Figures S3-1,-2, lower panels); the probes (Rm4, Rm2, and Fm5) whose three-base substitutions (GGA, GGC, and GGC) are located within C1-1, iC1-2 and C2-2, respectively. Kd for SinR binding to Rm0 was approximately 50 nM, whereas Kd for SinR binding to Fm0 was more than 400 nM (Supplementary Figures S3-1,-2). SinR did not bind to SinR-1 of Rm2 and Rm4 at 200 nM of the SinR concentration and it did not bind to SinR-2 of Fm5 at 800 nM, clearly confirming that C1-1 and iC1-2, and C2-2 are necessary for SinR binding to SinR-1 and SinR-2, respectively.

The overall EMSA analyses clearly indicated that SinR binds to SinR-1 consisting of C1-1 and iC1-2 for transcription repression of PkinB and it binds to SinR-2 consisting of C2-1 and C2-2 for its positive stringent transcription control.

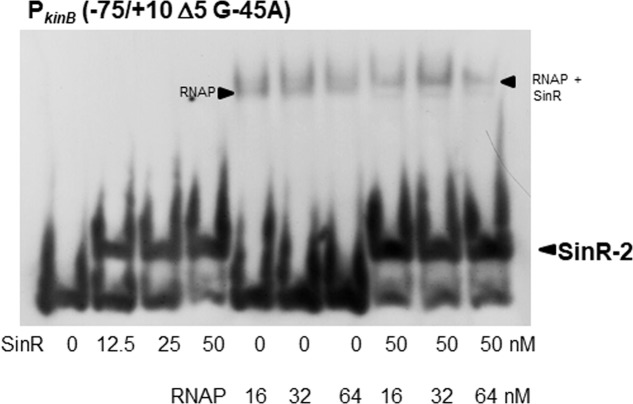

EMSA Analysis of the Binding of SinR and RNA Polymerase (RNAP) to the PkinB Region

We found that SinR-2 consists of C2-1 and C2-2 in tandem arrangement, which is likely involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB. C2-1 and C2-2 partially overlap the ‘-35’ and ‘-10’ regions of PkinB (Figure 1), so it was expected that SinR might bind to SinR-2 to form a transcription initiation complex of SinR, RNAP, and PkinB to exert its positive stringent transcription control. As shown in Figure 10, the electrophoretic band of a complex of the PkinB probe and RNAP appeared to shift to a slightly slower position when SinR was further added. This implies that a positively regulated stringent promoter such as PkinB might form a transcription initiation complex with SinR and RNAP for its positive stringent transcription control.

FIGURE 10.

EMSA analysis of the binding of SinR and RNA polymerase (RNAP) to the PkinB region. The PkinB (–75/+10 Δ5 and G-45A) probe was used for EMSA. The slightly lower and upper arrowheads denote the positions of the complexes of SinR and the probe, and of RNAP, SinR and the probe, respectively.

Discussion

ppGpp is synthesized by the RelA protein associated with ribosomes upon amino acid starvation (Fujita et al., 2012). In the case of E. coli, the target of ppGpp is RNAP, stringent genes being regulated positively and negatively, depending on their specific promoter sequences. In contrast, the ppGpp target is GMP kinase in B. subtilis, the in vivo GTP concentration being reduced (Kriel et al., 2012). The GTP concentration also decreased upon addition of decoyinine, an inhibitor of GMP synthase (Tojo et al., 2008). The GTP decrease reciprocally results in an ATP increase via feedback regulation (Tojo et al., 2010, 2013). The transcription initiation of negative stringent control genes such as rrn, ptsG, and pdhA, whose transcription initiation base is guanine, is reduced upon a GTP decrease, whereas that of positive stringent control genes such as ilvB, pycA, kinB, and kinA, whose transcription initiation base is adenine, is enhanced upon an ATP increase (Krásný and Gourse, 2004; Krásný et al., 2008; Tojo et al., 2008, 2010, 2013).

Decoyinine induces sporulation of B. subtilis cells exponentially growing in the presence of rapidly metabolizable carbon, nitrogen, and phosphate sources (Mitani et al., 1977). It is known that the stringent response also induces sporulation (Ochi et al., 1981, 1982). Recently, decoyinine was found to induce positive stringent transcription control of the kinB gene encoding a trigger of sporulation (Tojo et al., 2013), which might be the reason why decoyinine induces sporulation. The lacZ-fusion analysis using the mutant cells carrying the A+1G substitution (Figure 2) disclosed that positive stringent transcription control has a larger contribution to kinB expression in decoyinine-induced sporulation in minimal S6 medium than in sporulation in nutrient NSMP medium. Both kinB repression by SinR and SinR-dependent positive stringent transcription control of PkinB simultaneously occur, as inferred from that approx. 1.5-fold positive stringent transcription control of PkinB was constantly and steadily observed after decoyinine addition to the S6 culture, regardless of the level of kinB repression before decoynine addition (Figures 3, 4).

The sinR strain exhibits the sporulation-deficient phenotype when present in multiple copies (Gaur et al., 1986). The ΔsinR strain sporulated a little bit better than the wild-type strain. The kinB gene was repressed by SinR (Dartois et al., 1996) (Figure 4). SinR was also involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB (Figures 4, 5). SinI is an antagonist of SinR (Bai et al., 1993; Chai et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2008), which is induced by Spo0A∼P (Shafikhani et al., 2002; Lopez et al., 2009). SinI induced during sporulation initiation eventually inhibits SinR, leading to relief of kinB repression through SinR detachment from its binding site. Thus, SinI deficiency resulted in stronger SinR-dependent repression and reduced derepression (Figure 6). SrlR, a protein homologous to SinR (Kobayashi, 2008), was unlikely involved in the relief from this SinR repression. Furthermore, neither SinI nor SrlR was involved in its positive stringent transcription control (Figure 6).

It should be noted that the relief from kinB repression caused by SinR, presumably mediated by SinI, is supposed to be quite insufficient for sporulation to proceed, as observed for sporulation in NSMP and for decoyinine-induced sporulation in the wild-type sinR+ genetic background (Figures 3, 4). Thus, in the wild-type SinR+ cells, the limited level of derepression of kinB from SinR repression by SinI induced by Spo0A∼P and significant induction of SinR-dependent positive stringent transcription control of PkinB upon stringent response cooperatively induce effective sporulation. It is inferred from the results (Figures 4, 6) that the level of kinB expression on sporulation of the wild-type strain is likely lower than that on sporulation of the ΔsinR strain even if positive stringent transcription control is blocked by ΔsinR. This might be the reason why the ΔsinR strain sporulated a little bit better than the wild-type strain.

Examination of the sequence of the PkinB region revealed two SinR binding sites (SinR-1 and SinR-2), i. e. a pair of SinR consensus sequences (C1-1 and iC1-2) in an inverted orientation, and another pair of SinR ones (C2-1 and C2-2) in a tandem arrangement, respectively (Figure 1). Such SinR-binding motifs consisting of a pair of SinR consensus sequences in an inverted orientation and a tandem arrangement are often observed in the promoter regions of the operons involved in biofilm formation such as espA-O (Kearns et al., 2005) and tapA-sipW-tasA (Chu et al., 2006). In vivo deletion and base substitution analyses of SinR-1 for kinB repression (Figures 3, 4) and EMSA using various deleted and mutated probes (Figures 7–9) revealed that both C1-1 and iC1-2 are necessary for kinB repression and SinR binding to SinR-1. Moreover, the base substitution in C2-1, which was involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB (Figure 5), also affected SinR binding to SinR-2 (Figure 7). EMSA using various deleted and mutated probes (Figures 8, 9) suggested that both C2-1and C2-2 are necessary for SinR binding to SinR-2.

The sinR deletion (ΔsinR) abolished positive stringent transcription control of PkinB (Figure 4). lacZ-fusion analysis of the other stringently-controlled promoters (unpublished observation by S. Nii and Y. Fujita) indicated that ΔsinR also abolished the positive stringent transcription control of PilvB, PpycA, and PkinA. Interestingly, ΔsinR did not affect the negative stringent transcription control of PptsG and PpdhA. This observation suggested that positive stringent transcription control involves SinR, but negative stringent transcription control does not involve it. EMSA analyses (Figures 7–9) showed that the PkinB region actually possesses an SinR-binding site (SinR-2), i. e. a pair of C2-1 and C2-2 sequences partially overlapping the ‘-35’ and ‘-10’ regions, respectively, which is likely involved in positive stringent transcription control of PkinB (Figure 5). Furthermore, EMSA indicated that a complex of RNAP, SinR, and PkinB for transcription initiation is likely formed, implying that SinR might be involved in transcription initiation of positively controlled stringent genes (Figure 10). Detailed investigation of the molecular mechanism involving SinR underlying positive stringent transcription control is in progress.

Author Contributions

YF, SN, and KH performed in vivo study of kinB regulation by SinR in B. subtilis from April 2015 to March 2017 in Fukuyama University. YF moved from Fukuyama University to Tokai University April 2017. YF and MO (Tokai University) performed in vitro study of this work from April 2016 to July 2017.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. Ochi for giving us the decoyinine (Eli Lilly; not commercially available any more).

Funding. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants, numbers 15K07374 and 15K07367. It was also supported by the Research Programs of the Green Science Research Center, Fukuyama University, and the Institute of Oceanic Research and Development, Tokai University.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02502/full#supplementary-material

References

- Anagnostopoulos C., Spizizen J. (1961). Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 81 741–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai U., Mandic-Mulec I., Smith I. (1993). SinI modulates the activity of SinR, a developmental switch protein of Bacillus subtilis, by protein-protein interaction. Genes Dev. 7 139–148. 10.1101/gad.7.1.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervin M. A., Lewis R. J., Brannigan J. A., Spiegelman G. B. (1998). The Bacillus subtilis regulator SinR inhibits spoIIG promoter transcription in vitro without displacing RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 26 3806–3812. 10.1093/nar/26.16.3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y., Chu F., Kolter R., Losick R. (2008). Bistability and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 67 254–263. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06040.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y., Norman T., Kolter R., Losick R. (2010). An epigenetic switch governing daughter cell separation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 24 754–765. 10.1101/gad.1915010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F., Kearns D. B., Branda S. S., Kolter R., Losick R. (2006). Targets of the master regulator of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 59 1216–1228. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F., Kearns D. B., McLoon A., Chai Y., Kolter R., Losick R. (2008). A novel regulatory protein governing biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 68 1117–1127. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06201.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge V. L., Fogg M. J., Levdikov V. M., Leech A., Dodson E. J., Wilkinson A. J. (2011). Structure and organization of SinR, the master regulator of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 411 597–613. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartois V., Djavakhishvili T., Hoch J. A. (1996). Identification of a membrane protein involved in activation of the KinB pathway to sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178 1178–1186. 10.1128/jb.178.4.1178-1186.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartois V., Djavakhishvilli T., Hoch J. A. (1997). KapB is a lipoprotein required for KinB signal transduction and activation of the phosphorelay to sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 26 1097–1108. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6542024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Freese E. (1981). Isolation and properties of a Bacillus subtilis mutant unable to produce fructose-bisphosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 145 760–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Tojo S., Hirooka K. (2012). “Stringent transcription control of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis,” in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis: The Frontiers of Molecular Microbiology Revisited eds Sadaie Y., Matsumoto K. (Kerala: Research Signpost; ) 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur N. K., Dubnau E., Smith I. (1986). Characterization of a cloned Bacillus subtilis gene that inhibita sporulation in multiple copies. J. Bacteriol. 168 860–869. 10.1128/jb.168.2.860-869.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch J. A. (1993). Regulation of the phosphorelay and the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47 441–465. 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns D. B., Chu F., Branda S. S., Kolter R., Losick R. (2005). A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55 739–749. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K. (2008). SlrR/SlrA controls the initiation of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 69 1399–1410. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krásný L., Gourse R. L. (2004). An alternative strategy for bacterial ribosome synthesis: Bacillus subtilis rRNA transcription regulation. EMBO J. 23 4473–4483. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krásný L., Tišerová H., Jonák J., Rejman D., Sanderová H. (2008). The identity of the transcription +1 position is crucial for changes in gene expression in response to amino acid starvation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 69 42–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06256.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriel A., Bittner A. N., Kim S. H., Liu K., Tehranchi A. K., Zou W. Y., et al. (2012). Direct regulation of GTP homeostasis by (p)ppGpp: a critical component of viability and stress resistance. Mol. Cell 48 231–241. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez D., Vlamakis H., Kolter R. (2009). Generation of multiple cell types in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33 152–163. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michna R. H., Zhu B., Mäder U., Stülke J. (2016). SubtiWiki 2.0–an integrated database for the model organism Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D654–D662. 10.1093/nar/gkv1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani T., Heinze J. E., Freese E. (1977). Induction of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis by decoyinine or hadacidin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 77 1118–1125. 10.1016/S0006-291X(77)80094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa Y., Fujita Y. (2001). Involvement of two distinct catabolite-responsive elements in catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis myo-inositol (iol) operon. J. Bacteriol. 183 5877–5884. 10.1128/JB.183.20.5877-5884.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molle V., Nakaura Y., Shivers R. P., Yamaguchi H., Losick R., Fujita Y., et al. (2003). Additional targets of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation and genome-wide transcript analysis. J. Bacteriol. 185 1911–1922. 10.1128/JB.185.6.1911-1922.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. A., Rodrigues C., Lewis R. J. (2013). Molecular basis of the activity of SinR protein, the master regulator of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 288 10766–10778. 10.1074/jbc.M113.455592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi K., Kandala J. C., Freese E. (1981). Initiation of Bacillus subtilis sporulation by the stringent response to partial amino acid deprivation. J. Biol. Chem. 256 6866–6875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi K., Kandala J. C., Freese E. (1982). Evidence that Bacillus subtilis sporulation induced by the stringent response is caused by the decrease in GTP or GDP. J. Bacteriol. 151 1062–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M. (2016). Post-transcriptionally generated cell heterogeneity regulates biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Cells 21 335–349. 10.1111/gtc.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M., Tanaka T. (1996). Transcription of Bacillus subtilis degR is σD-dependent and suppressed by multicopy proB through σD. J. Bacteriol. 178 216–222. 10.1128/jb.178.1.216-222.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M., Yoshikawa H., Chibazakura T. (2014). Regulation of the response regulator gene degU through the binding of SinR/SlrR and exclusion of SinR/SlrR by DegU in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 196 873–881. 10.1128/JB.01321-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predich M., Nair G., Smith I. (1992). Bacillus subtilis early sporulation genes kinA, spo0F, and spo0A are transcribed by the RNA polymerase containing sigma H. J. Bacteriol. 174 2771–2778. 10.1128/jb.174.9.2771-2778.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2001). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Edn New York, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shafikhani S. H., Mandic-Mulec I., Strauch M. A., Smith I., Leighton T. (2002). Postexponential regulation of sin operon expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184 564–571. 10.1128/JB.184.2.564-571.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson K., Hoch J. A. (2002). Evolution of signaling in the sporulation phosphorelay. Mol. Microbiol. 46 297–304. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P. S., Franklin M. J. (2008). Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 199–210. 10.1038/nrmicro1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauch M. A. (1995). Delineation of AbrB-binding sites on the Bacillus subtilis spo0H, kinB, ftsAZ, and pbpE promoters and use of a derived homology to identify a previously unsuspected binding site in the bsuB1 methylase promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177 6999–7002. 10.1128/jb.177.23.6999-7002.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauch M. A., Webb V., Spiegelman G., Hoch J. A. (1990). The SpoOA protein of Bacillus subtilis is a repressor of the abrB gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87 1801–1805. 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tojo S., Hirooka K., Fujita Y. (2013). Expression of kinA and kinB of Bacillus subtilis, necessary for sporulation initiation, is under positive stringent transcription control. J. Bacteriol. 195 1656–1665. 10.1128/JB.02131-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tojo S., Kumamoto K., Hirooka K., Fujita Y. (2010). Heavy involvement of stringent transcription control depending on the adenine or guanine species of the transcription initiation site in glucose and pyruvate metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 192 1573–1585. 10.1128/JB.01394-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tojo S., Satomura T., Kumamoto K., Hirooka K., Fujita Y. (2008). Molecular mechanisms underlying the positive stringent response of the Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon, involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids. J. Bacteriol. 190 6134–6147. 10.1128/JB.00606-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trach K. A., Hoch J. A. (1993). Multisensory activation of the phosphorelay initiating sporulation in Bacillus subtilis: identification and sequence of the protein kinase of the alternate pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 8 69–79. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlamakis H., Chai Y., Beauregard P., Losick R., Kolter R. (2013). Sticking together: building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 157–168. 10.1038/nrmicro2960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K., Mien Y. L., Sadaie Y., Asai K. (2011). Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase incorporates digoxigenin-labeled nucleotide in vitro. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 57 153–157. 10.2323/jgam.57.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., Ishio I., Nagakawa E., Yamamoto Y., Yamamoto M., Fujita Y. (2000). Systematic study of gene expression and transcription organization in the gntZ-ywaA region of the Bacillus subtilis genome. Microbiology 146 573–579. 10.1099/00221287-146-3-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.