Abstract

Introduction

Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), depressive symptoms, and fatigue are common after stroke and are associated with reduced quality of life. We prospectively investigated their prevalence and course after a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or nonfocal transient neurological attack (TNA) and the association with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) lesions.

Methods

The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Subjective Fatigue subscale from the Checklist Individual Strength were used to assess subjective complaints shortly after TIA or TNA and six months later. With repeated measure analysis, the associations between DWI lesion presence or clinical diagnosis (TIA or TNA) and subjective complaints over time were determined.

Results

We included 103 patients (28 DWI positive). At baseline, SCI and fatigue were less severe in DWI positive than in DWI negative patients, whereas at follow-up, there were no differences. SCI (p = 0.02) and fatigue (p = 0.01) increased in severity only in DWI positive patients. There were no differences between TIA and TNA.

Conclusions

Subjective complaints are highly prevalent in TIA and TNA patients. The short-term prognosis is not different between DWI-positive and DWI negative patients, but SCI and fatigue increase in severity within six months after the event when an initial DWI lesion is present.

1. Introduction

Subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), depressive symptoms, and fatigue are highly prevalent after stroke and are related to stroke severity [1–4]. Although by definition the symptoms of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) subside completely within 24 hours [5], subjective cognitive complaints, depressive symptoms, and fatigue often persist in these patients as well [6–8].

Diagnosing TIA is notoriously difficult [9]. Patients often report attacks of atypical or nonfocal neurological symptoms. In the absence of an alternative diagnosis, these episodes are referred to as transient neurological attack (TNA) [10]. In one-third of TIA patients, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) shows signs of acute ischemia beyond the point of symptom resolution, ascertaining a cerebrovascular etiology of the attack [11]. Acute DWI lesions are however also present in more than 20% of clinically diagnosed TNA patients [12].

Previous studies on subjective complaints after short-lasting attacks of neurological symptoms have focused solely on TIA, did not take DWI findings into account, and were cross-sectional in nature [6–8]. Since subjective complaints are associated with a reduced quality of life and are possible harbingers of forthcoming cognitive decline, it is important to understand their prevalence and determinants [13, 14].

We prospectively investigated the prevalence, severity, and course of SCI, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and fatigue in a cohort of TIA and TNA patients and determined the relation with event type and DWI results. We hypothesized that patients with acute DWI lesions would report an increase in severity of complaints in the months after the initial event. Since TIA and TNA have a comparable prevalence of DWI positivity, we expected to find no differences between these patient categories [12].

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

This study was part of the prospective Cohort study ON Neuroimaging, Etiology, and Cognitive consequences of Transient neurological attacks (CONNECT), the details of which have been previously reported [15]. Consecutive stroke-free patients aged ≥ 45 years referred to a specialized outpatient TIA clinic within 7 days after an event of acute onset neurological symptoms lasting < 24 hours were included. Baseline measurements took place within seven days after the qualifying event, and follow-up was performed six months later. All baseline assessments were performed before the final diagnosis was discussed with the patient. The Medical Review Ethics Committee region Arnhem-Nijmegen approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Classification of Qualifying Event

Based on a detailed description of the signs and symptoms of the event including a structured assessment of the presence or absence of eighteen specific predefined symptoms (Table 1), three specialized stroke neurologists adjudicated each event as TIA, TNA, or a specified other diagnosis, using previously determined definitions of TIA and TNA [5, 10]. Events with both focal and nonfocal symptoms were classified as TIA. Qualifying neurologists were blinded to results from MRI, and in case of disagreement, a consensus meeting was held.

Table 1.

Predefined focal and nonfocal neurological symptoms.

| Focal | Nonfocal |

|---|---|

| Hemiparesis | Decreased consciousness or unconsciousness |

| Hemihypesthesia | Confusion |

| Dysphasia | Amnesia |

| Dysarthria | Unsteadiness |

| Hemianopia | Nonrotatory dizziness |

| Transient monocular blindness | Positive visual phenomena |

| Hemiataxia | Paresthesias |

| Diplopia | Bilateral weakness of arms or legs |

| Vertigo | Unwell feelings∗ |

Symptoms should have sudden onset, rapid clearance, and duration of <24 hours. ∗Referable to the nervous system if the referring physician considered TIA but patients were unable to specify further.

2.3. Brain Imaging

Brain MRI was performed within seven days after the qualifying event on a 1.5 Tesla Magnetom Scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and included DWI, FLAIR, T1-, T2-, and T2∗-weighted sequences. Two experienced raters individually evaluated the severity of white matter hyperintensities, the presence of (silent) territorial infarcts, lacunes, and microbleeds [16, 17]. DWI was visually assessed for signs of acute infarction. Raters were unaware of clinical information, and a consensus meeting was held in case of disagreement.

2.4. Subjective Cognitive Impairment

At baseline and follow-up, the presence and severity of SCI in the previous month was assessed with a 15-item semistructured interview based on the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) [18]. Items concerning remembering, word finding, planning, concentration, and slowness of thought were given a wider score range (0–3) than other items (0-1). SCI was considered present if ≥1 moderate problem (score ≥ 2) on an item with a score range of 0 to 3 or a score of 1 on a dichotomous item was reported [19]. Trained examiners, unaware of clinical diagnosis and DWI status, administered all semistructured interviews.

2.5. Other Measurements

At both baseline and follow-up, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was administered to measure the severity of symptoms of depression and anxiety [20]. Relevant symptoms of depression or anxiety were defined as a value of >7 on the subscales [21]. Fatigue was assessed with the subscale Subjective Fatigue of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R-fatigue) with a score > 35 considered indicative for severe fatigue [22]. Level of education was classified using seven categories (1 = less than primary school; 7 = academic degree) [23]. Vascular risk factors were assessed at baseline. Incident vascular events (stroke, TIA, and myocardial infarction) between baseline and follow-up were assessed with a standardized, structured questionnaire. All questionnaires were handed out at the baseline or follow-up visit. In case of limited time, these were filled in at home and returned within one week.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Only patients who completed follow-up were included. Baseline characteristics were compared between patients with complete and incomplete follow-up, between TIA and TNA between patients, and patients with and without DWI lesion, using Student's t-test, χ2 test, or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate.

Differences in prevalence of SCI, symptoms of depression or anxiety, and severe fatigue between groups (clinical diagnosis and DWI status) and time points were analyzed with McNemar's test. Subsequently, the effect of DWI lesion and clinical diagnosis on change in subjective outcomes over time was determined with repeated measures analyses of variance. Associations between SCI, fatigue, and depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed with multivariate regression analysis.

Age, sex, and level of education were regarded as potential confounders and adjusted for in all repeated measures analyses. Alpha was set at 0.05 and statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

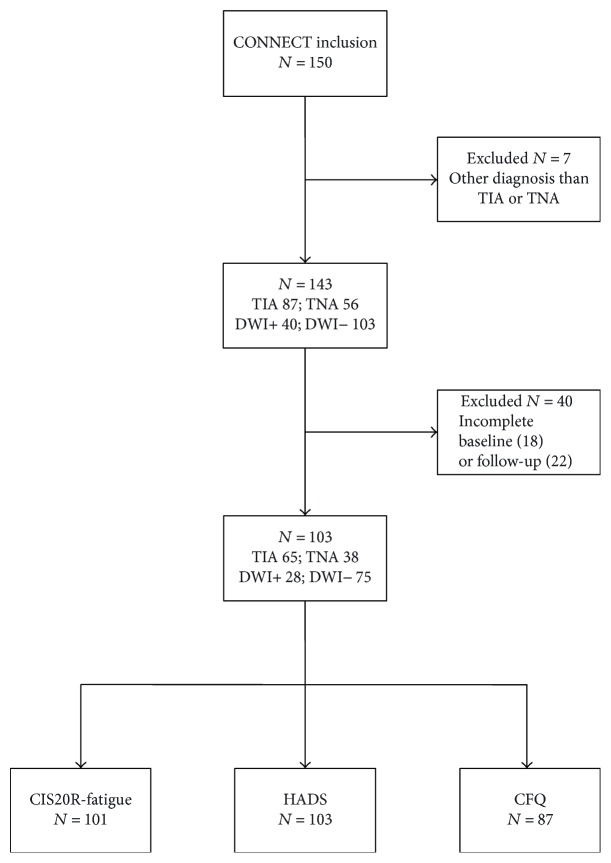

CONNECT included 150 patients, 87 of whom were diagnosed as TIA, 56 as TNA, and 7 with a specific diagnosis. Patients in the last category were excluded from further analyses, as were those with incomplete baseline or follow-up assessments, leading to 103 included patients (Figure 1). Reasons for incomplete assessment were failure to return questionnaires (>95%) and refusal (<5%). Patients with incomplete HADS or CIS20R-fatigue were slightly younger (mean 61.8 [SD 10.7] years versus 65.8 [SD 9.1] years, p = 0.04) than those with complete evaluations. There were no differences concerning clinical diagnosis, DWI lesion presence, level of education, or presence of vascular risk factors between patients with complete and incomplete assessments. Baseline characteristics of participants with complete assessments are presented by DWI results in Table 2. DWI lesions were more often present in clinically defined TIA patients, although 13% of included TNA patients also had a DWI lesion. Most DWI lesions were small cortical or subcortical lesions. There were no incident strokes or myocardial infarctions between baseline and follow-up, and five patients had an incident TIA. Excluding patients with incident TIA from the analyses did not change the results.

Figure 1.

Study population. CFQ: Cognitive Failures Questionnaire; CIS20R-fatigue: Checklist Individual Strength, fatigue subscale; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; TIA: transient ischemic attack; TNA: transient neurological attack.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics stratified by DWI result (n = 103).

| DWI+ (n = 28) |

DWI− (n = 75) |

p ∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 8 (29) | 29 (39) | 0.34 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 66.7 (8.5) | 65.6 (9.3) | 0.60 |

| Level of education, median (IQR) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 0.10 |

| TIA | 23 (82) | 42 (56) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 25 (89) | 60 (80) | 0.27 |

| Dyslipidemia | 18 (64) | 53 (71) | 0.53 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (7) | 7 (9) | 0.73 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (11) | 10 (13) | 0.72 |

| Smoking | 13 (46) | 17 (23) | 0.02 |

| Diffusion-weighted imaging lesions, total n | 45 | N/A | N/A |

| Lesion type | |||

| Small cortical | 26 (58) | ||

| Small subcortical | 14 (31) | ||

| Territorial | 5 (11) | ||

| Fazekas score, median (IQR) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.30 |

| Lacunes | 5 (18) | 12 (16) | 0.82 |

| Territorial infarcts | 2 (7) | 8 (11) | 0.59 |

| Microbleeds (available for 72 patients) | 1 (6) | 6 (11) | 0.49 |

Values are n (%) unless stated otherwise. ∗For difference using Student's t-test, χ2 test, or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; IQR: interquartile range; TIA: transient ischemic attack; N/A: not applicable.

3.1. Subjective Cognitive Impairment (n = 87)

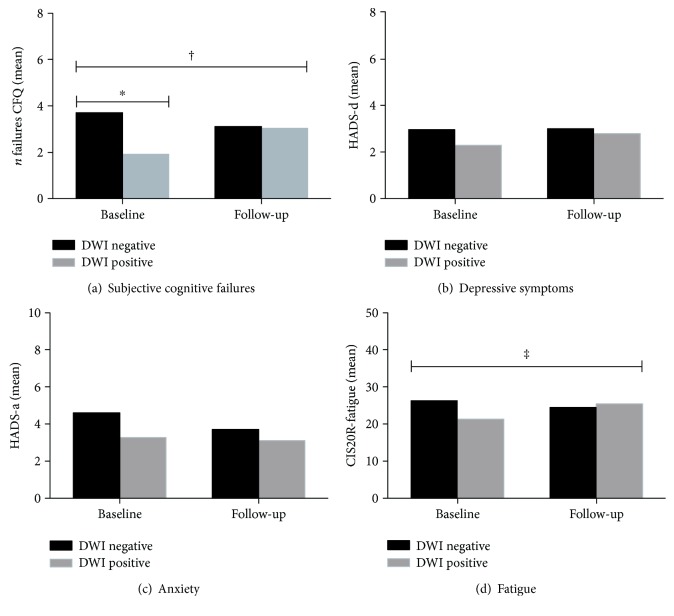

The overall prevalence of SCI in TIA and TNA patients was 82% at baseline and 77% at follow-up and was not significantly different between time points, DWI status, or clinical diagnosis. At baseline, the mean number of subjective cognitive failures was lower in patients with a DWI lesion than in those without (mean (SD) 1.83 (1.75) versus 3.77 (3.27), p = 0.01), while at follow-up, this increased to 3.00 (2.70) in the first group and decreased slightly to 3.14 (3.17) in the latter (p = 0.73) (Figure 2(a)). Repeated measures analysis (adjusted for age, sex, and level of education) showed that change over time in the number of subjective cognitive failures was significantly different between DWI positive and DWI negative patients (p = 0.01). There was no difference in SCI between TIA and TNA patients.

Figure 2.

Subjective cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and fatigue at baseline and follow-up in transient neurological attack patients with and without diffusion-weighted imaging lesions. CFQ: Cognitive Failures Questionnaire; CIS20R-fatigue: Checklist Individual Strength, fatigue subscale; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; HADS-a: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, anxiety; HADS-d: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, depression. ∗p = 0.02, analysis of covariance, adjusted for age, sex, and level of education. †p = 0.02, ‡p = 0.01, repeated measures analysis for the difference in change over time between DWI negative and DWI positive patients, adjusted for age, sex, and level of education.

3.2. Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety (n = 103)

Relevant depressive symptoms (HADS-depression subscore > 7) were present in 8% of all patients at baseline and 9% at follow-up. The prevalence of relevant anxiety symptoms (HADS-anxiety subscore > 7) was 15% at baseline and 11% at follow-up. Depressive and anxiety symptoms did not differ between DWI negative and DWI positive patients or between TIA and TNA patient groups (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)).

3.3. Fatigue (n = 101)

Severe fatigue (CIS20R-fatigue score > 35) was present in 23% of patients at baseline and in 19% six months later. Prevalence of severe fatigue did not differ between DWI positive and DWI negative patients or between TIA and TNA patients.

Mean (SD) CIS20R-fatigue score was 25.0 (12.7) at baseline and 24.8 (11.5) at follow-up. Baseline scores were lower in DWI positive patients (21.0 (12.7) compared to 26.6 (12.4) for those without; p = 0.07) but equal at follow-up (24.9 (11.6) in the DWI positive group versus 24.7 (11.6) in the DWI negative group; p = 0.86). Patients with and without DWI lesions differed with respect to change in CIS20R-fatigue scores (p = 0.01) (Figure 2(d)). The clinical diagnosis was unrelated to severity or change over time of fatigue.

At both baseline and follow-up, SCI was associated with higher CIS20R-fatigue scores (p = 0.001), but not with symptoms of depression or anxiety.

4. Discussion

Subjective complaints, especially SCI and fatigue, are highly prevalent in TIA and TNA patients both directly before the event and after six months. The initial qualifying diagnosis was unrelated to the presence, severity, and course of subjective complaints. Patients with signs of acute ischemia on DWI reported less severe SCI and fatigue in the month before the TIA or TNA than those without such a lesion. In this group of patients, severity subsequently increased in the six months after the event to a level equal to that of DWI negative patients.

Some methodological issues need to be considered when interpreting these results. First, given the loss to follow-up, selection bias might have occurred. Patients with missing follow-up HADS and CIS20R-fatigue assessments were on average slightly younger than participants. Since especially fatigue is more often reported in older patients, this might have resulted in an overestimation of its prevalence [24]. Alternatively, patients with incomplete assessments might have dropped out because of complaints, resulting in an underestimation. Other demographic variables however did not differ between patients with and without complete assessments, and we adjusted for age in our analyses. Therefore, we feel that selection bias has not largely influenced our results. The relatively small patient numbers in our study however limit statistical power, and our results need to be replicated in a larger cohort. Secondly, we used questionnaires to obtain information on the presence of SCI, depression, anxiety, and fatigue. These screening instruments, although validated, indicate whether patients experience dysfunction when actively asked about it. This differs from spontaneously reported complaints and may explain the high frequency of SCI observed in our cohort. The CFQ handles a strict cutoff for SCI, making it a sensitive but perhaps not very specific screening instrument. Thirdly, our study did not include a control group, limiting the interpretation of an added effect of TIA or TNA on subjective complaints.

The prevalence of SCI in our study is comparable to that in both stroke patients and those with evidence of small vessel disease on neuroimaging, using the same screening instrument [2, 19, 25]. Patients in those studies were on average older, had more often suffered stroke instead of TIA, and were tested several years after the initial event. Also, vascular lesions on neuroimaging were relatively sparse in our cohort, as compared to these studies [19, 25]. The high prevalence of SCI in TIA and TNA patients is therefore remarkable. Severe fatigue was less prevalent in our patients than in other stroke cohorts, as were depressive symptoms [4, 26, 27].

Interestingly, DWI positive patients reported less subjective cognitive failures and fatigue in the month before the event than those without a lesion. The DWI positive group by definition consisted of patients with a recent cerebrovascular event, independent of the clinical diagnosis. The DWI negative group possibly included some patients whose transient complaints have noncerebrovascular causes such as somatization, depression, or anxiety. Although this may explain the higher prevalence of premorbid SCI and fatigue, the lack of observed higher frequencies of depressive or anxiety symptoms does not support this hypothesis. Furthermore, we found no changes in subjective complaints in the DWI negative group, although one could expect these to increase after a disturbing event such as a TIA or TNA.

Within six months after TIA or TNA, severity of SCI and fatigue increased significantly in DWI positive patients. This can be explained in several ways. First, DWI hyperintensities are associated with permanent brain damage, which in turn is associated with cognitive decline, SCI, mood disorders, and fatigue in stroke patients [1, 3, 4, 28, 29]. Although the exact etiology remains to be established, a relationship between minor cognitive decline and recent lacunar infarct has been suggested [30]. Since the DWI lesions in our cohort were predominantly small cortical and subcortical lesions, a similar relationship may exist between these lesions and increasing subjective complaints over time. Second, the knowledge of having a DWI lesion could have influenced the perception of cognitive performance and have led to more subjective cognitive complaints. Third, secondary preventive medications including statins will more often have been started in the DWI positive patient group. Statins have been associated with cognitive complaints and fatigue. However, there are no consistent negative effects of statins on these outcome measures [31]. Finally, the increase in severity of SCI and fatigue observed in the DWI positive patient group could be merely a correction of an unexplained baseline difference, that is, regression towards the mean. However, no changes in prevalence or severity of these complaints were found in the DWI negative group, countering this explanation.

Fatigue was associated with subjective cognitive dysfunction. Possibly, both fatigue and SCI, as measured in our study, are expressions of the same underlying sense of unwell-being. We found no association between depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive dysfunction, suggesting that the increased severity of SCI observed in DWI positive patients was not influenced by mood changes.

5. Conclusions

Subjective complaints are highly prevalent in TIA and TNA patients. Larger sampled studies with longer follow-up need to determine whether subjective complaints last beyond six months after TIA or TNA and assess the course over time with respect to DWI lesion presence and the association with cognitive performance. Furthermore, the etiology of subjective cognitive impairment and fatigue after short-lasting cerebral ischemia and the association with radiological markers of cerebrovascular damage such as lacunes and cerebral atrophy should be subject to further research. Our results nevertheless add to the growing notion that TIA and TNA are more than just transient attacks but are associated with ongoing deficits and problems. This can be used to inform patients on the potential long-term prognosis of their TIA or TNA.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a fellowship from the Netherlands Brain Foundation received by Dr. Ewoud J. van Dijk (Grant F2009(1)-16).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lamb F., Anderson J., Saling M., Dewey H. Predictors of subjective cognitive complaint in postacute older adult stroke patients. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;94(9):1747–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maaijwee N. A., Schaapsmeerders P., Rutten-Jacobs L. C., et al. Subjective cognitive failures after stroke in young adults: prevalent but not related to cognitive impairment. Journal of Neurology. 2014;261(7):1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Husseini N., Goldstein L. B., Peterson E. D., et al. Depression and antidepressant use after stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43(6):1609–1616. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.643130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerdal A., Bakken L. N., Kouwenhoven S. E., et al. Poststroke fatigue—a review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;38(6):928–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Committee. Special report from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Classification of cerebrovascular diseases III. Stroke. 1990;21(4):637–676. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.21.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fens M., van Heugten C. M., Beusmans G. H., et al. Not as transient: patients with transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke experience cognitive and communication problems; an exploratory study. The European Journal of General Practice. 2013;19(1):11–16. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2012.715147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luijendijk H. J., Stricker B. H., Wieberdink R. G., et al. Transient ischemic attack and incident depression. Stroke. 2011;42(7):1857–1861. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winward C., Sackley C., Metha Z., Rothwell P. M. A population-based study of the prevalence of fatigue after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(3):757–761. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.527101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castle J., Mlynash M., Lee K., et al. Agreement regarding diagnosis of transient ischemic attack fairly low among stroke-trained neurologists. Stroke. 2010;41(7):1367–1370. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos M. J., van Rijn M. J., Witteman J. C., Hofman A., Koudstaal P. J., Breteler M. M. Incidence and prognosis of transient neurological attacks. JAMA. 2007;298(24):2877–2885. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.24.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazzelli M., Chappell F. M., Miranda H., et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging and diagnosis of transient ischemic attack. Annals of Neurology. 2014;75(1):67–76. doi: 10.1002/ana.24026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rooij F. G., Vermeer S. E., Goraj B. M., et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in transient neurological attacks. Annals of Neurology. 2015;78(6):1005–1010. doi: 10.1002/ana.24539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montejo P., Montenegro M., Fernandez M. A., Maestu F. Memory complaints in the elderly: quality of life and daily living activities. A population based study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2012;54(2):298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kryscio R. J., Abner E. L., Cooper G. E., et al. Self-reported memory complaints: implications from a longitudinal cohort with autopsies. Neurology. 2014;83(15):1359–1365. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rooij F. G., Tuladhar A. M., Kessels R. P., et al. Cohort study ON Neuroimaging, Etiology and Cognitive consequences of Transient neurological attacks (CONNECT): study rationale and protocol. BMC Neurology. 2015;15(1):p. 36. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fazekas F., Chawluk J. B., Alavi A., Hurtig H. I., Zimmerman R. A. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1987;149(2):351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardlaw J. M., Smith E. E., Biessels G. J., et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(8):822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broadbent D. E., Cooper P. F., FitzGerald P., Parkes K. R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;21(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Groot J. C., de Leeuw F. E., Oudkerk M., Hofman A., Jolles J., Breteler M. M. Cerebral white matter lesions and subjective cognitive dysfunction: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2001;56(11):1539–1545. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.11.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjelland I., Dahl A. A., Haug T. T., Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vercoulen J. H., Swanink C. M., Fennis J. F., Galama J. M., van der Meer J. W., Bleijenberg G. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38(5):383–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90099-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochstenbach J., Mulder T., van Limbeek J., Donders R., Schoonderwaldt H. Cognitive decline following stroke: a comprehensive study of cognitive decline following stroke∗. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1998;20(4):503–517. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.4.503.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loge J. H., Ekeberg O., Kaasa S. Fatigue in the general Norwegian population: normative data and associations. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1998;45(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Norden A. G., Fick W. F., de Laat K. F., et al. Subjective cognitive failures and hippocampal volume in elderly with white matter lesions. Neurology. 2008;71(15):1152–1159. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327564.44819.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maaijwee N. A., Arntz R. M., Rutten-Jacobs L. C., et al. Post-stroke fatigue and its association with poor functional outcome after stroke in young adults. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2015;86(10):1120–1126. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snaphaan L., van der Werf S., Kanselaar K., de Leeuw F. E. Post-stroke depressive symptoms are associated with post-stroke characteristics. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009;28(6):551–557. doi: 10.1159/000247598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oppenheim C., Lamy C., Touze E., et al. Do transient ischemic attacks with diffusion-weighted imaging abnormalities correspond to brain infarctions? American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2006;27(8):1782–1787. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pendlebury S. T., Rothwell P. M. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurology. 2009;8(11):1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanco-Rojas L., Arboix A., Canovas D., Grau-Olivares M., Oliva Morera J. C., Parra O. Cognitive profile in patients with a first-ever lacunar infarct with and without silent lacunes: a comparative study. BMC Neurology. 2013;13:p. 203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desai C. S., Martin S. S., Blumenthal R. S. Non-cardiovascular effects associated with statins. BMJ. 2014;349, article g3743 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]