Abstract

Background & Aims

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a syndrome characterized by an intense systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) and multi-organ system failure (MOSF). Platelet-derived microparticles increase in proportion to the severity of the SIRS and MOSF, and are associated with poor outcome. We investigated whether patients with ALF develop thrombocytopenia in proportion to the SIRS, MOSF, and poor outcome.

Methods

In a retrospective study, we collected data on post-admission platelet counts of 1598 patients included in the ALF Study Group Registry from 1998 through October, 2012. We investigated correlations between platelet counts and clinical features of ALF, laboratory test results, and outcomes. Of the patients studied, 752 (47%) survived without liver transplantation, 390 (24%) received liver transplants, and 517 (32%) died.

Results

In patients with SIRS, platelet counts decreased 2–7 days after admission, compared to patients without SIRS (P≤.001). Patients with abnormal levels of creatinine, phosphate, lactate, or bicarbonate had significantly lower platelet counts than patients with normal levels of these laboratories (all P≤.001). The decrease in platelets during days 1–7 after admission was proportional to the grade of hepatic encephalopathy and requirement for vasopressor and renal replacement therapy. Although platelet numbers decreased after admission in the overall population, platelets were significantly lower 2–7 days after admission in patients with outcomes of death or liver transplantation than in patients who made spontaneous recoveries and survived. In contrast, international normalized ratios over time were not associated with SIRS, laboratory test results associated with poor outcomes, grade of hepatic encephalopathy, or requirement for renal replacement therapy.

Conclusions

The development of thrombocytopenia in patients with ALF is associated with development of MOSF and poor outcome. We speculate that SIRS-induced activation of platelets, yielding microparticles, results in clearance of platelet remnants and subsequent thrombocytopenia.

Keywords: hemostasis, plasma membrane fragmentation, blood cell, INR

Introduction

The syndrome of acute liver failure (ALF) is characterized by deranged hemostasis and the development of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in a patient without previously known liver disease. In its most florid presentation, the primary liver injury initiates a systemic inflammatory response, resulting in multi-organ system failure (MOSF), which involves almost every organ system. Furthermore, a pro-thrombotic state within the microvasculature of the injured liver1 and peripheral tissues2 may exacerbate the primary liver injury and MOSF, respectively, with a secondary hypoxic injury. Although the severity of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)3 and laboratory markers of MOSF (pH, creatinine, ammonia, lactate, phosphate, and INR) correlate with poor outcome in ALF4–7, the mechanisms by which liver injury triggers MOSF and activation of hemostasis have not been well-defined.

Platelets are increasingly recognized as important mediators of the SIRS and MOSF in patients with sepsis and other critical illnesses8,9. Indeed, a decreasing platelet count after admission to an intensive care unit is an ominous sign strongly associated with death10,11. Platelets occupy a central role in coordinating hemostasis and inflammation, and both activate, and are activated by, systemic inflammation, leading to end-organ injury8,12. Some pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic functions of platelets are mediated by platelet microparticles, fragments of plasma membrane measuring 0.1–1.0μm, which are liberated following platelet activation and released into the circulation in response to the SIRS13.

Patients with ALF frequently develop thrombocytopenia by poorly understood mechanisms. Serum concentrations of thrombopoietin, a liver-derived hormone, do not correlate with the degree of thrombocytopenia and have been shown to be normal or increased in patients with ALF14, suggesting the presence of other mechanisms. In patients with ALF, we have recently shown that the plasma concentrations of pro-thrombotic microparticles, the majority of which were platelet-derived, increased in proportion to the severity of the SIRS15. Furthermore, concentrations of microparticles paralleled increased laboratory markers of poor outcome, the systemic complications of ALF (ie., MOSF) including progression to high grade HE, hypotension requiring vasopressors, renal failure, and death. As suggested by these data, if increased platelet-derived microparticles play a role in the pathogenesis of MOSF, we hypothesized that the converse would also be true, that the platelet count would decline after admission for ALF in proportion to the severity of the SIRS, development of MOSF, and poor outcome.

Herein, we test the hypothesis that a decline in platelet count after admission for ALF signifies activation of the SIRS, and predicts evolution to MOSF and poor outcome (LT or death). In order to demonstrate that changes in platelet count do not simply reflect the extent of liver injury, we compared the relationship of these clinical endpoints to the most important laboratory marker of liver injury, the International Normalized Ratio (INR) of the prothrombin time.

Methods

Patients and data collection

Consecutive participants in the ALF Study Group Registry from its inception in 1998 until October, 2012 were assessed for eligibility. Inclusion criteria included acute injury (defined as a jaundice-to-HE interval of <26 weeks), the presence of coagulopathy (defined as INR ≥1.5), the presence of HE, and the absence of a previously-identified chronic liver disease16. Laboratory data and systemic complications were collected for a maximum of seven days (ie., day 1-day 7) after enrollment. Data were no longer collected on patients who received a LT, were discharged from the hospital, or died. All 4 SIRS components were available for day 1 only. Of the 1,974 subjects enrolled before October 1, 2012, we restricted analysis to those patients who had complete bleeding, INR, and platelet measurements for the period from enrollment to last observation day. Of the patients in the Registry, 81% (N=1,598) had data available on day 1 and of these, 40% (N=636) and 43% (N=682) of subjects had INR and platelet data, respectively, for all 7 evaluable days (Supplemental Figure 1).

The ALF Study Group Registry has been approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating centers, and informed consent was obtained from the nearest-of-kin of all participants.

Definitions of complications and outcomes

Definition of the SIRS was according to standard criteria17. Components of MOSF were defined as follows: high grade (grade 3 or 4) HE according to standard West Haven Criteria; renal failure defined by the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT); and cardiovascular collapse defined as the need for vasopressors to maintain blood pressure in a range for adequate peripheral organ perfusion (not further specified). Spontaneous (transplant-free) survival, LT, and death were assessed at 21 days after enrollment.

Statistics

SAS software (version 9.3; Cary, NC) was used to perform statistical analyses. Baseline variables were described using counts and percentages for categorical data, or means and standard deviations (medians and interquartile ranges) for continuous normal (skewed) data. For variables identified as clinically relevant, statistical tests were performed using Chi-square, ANOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Modeling of platelet and INR values over time was performed using a linear mixed model with unstructured covariance for each patient to account for the within-patient correlation across measurement days. All figures illustrate mean platelet and INR estimates for each observation day adjusted for the correlation across measurement days (ie., least square means).

Some subjects received platelet and/or plasma transfusions within days 1–7 after enrollment, which could have affected the analysis of platelet count and INR, respectively. Specifically, 45% of patients received plasma and 9.8% platelets on day 1; the cumulative receipt of plasma and/or platelets for days 1–7 was 60% and 23%, respectively. The effects of plasma/platelets on the results of this study were also examined in statistical models using transfusion as a covariate.

All statistical tests are reported as two-sided with a type I error rate of 5%.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

Baseline demographic and median laboratory values for the 1598 study patients are depicted in Table 1. Young Caucasian women dominated the study population (mean age 41 years, 76% Caucasian, 70% female). Nearly half (47%) of study participants had ALF due to acetaminophen (APAP) overdose. Eighty-five percent of study subjects had at least one positive element of the SIRS on admission, 32% developed hypotension requiring vasopressors, 33% developed renal failure requiring RRT, 35% developed infectious complications, 50% developed high grade (grade 3 or 4) HE, and 14% underwent intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor placement for high grade HE during days 1–7 after enrollment. Of all study participants, 752 (47%) recovered without LT (spontaneous survivors), 390 (24%) underwent LT, and 517 (32%) died, 61 of whom died after LT (16% of those transplanted) by day 21. On admission to the hospital, 845 patients (55%) had the SIRS. The presence of the SIRS was significantly associated with admission laboratories associated with poor outcome, MOSF, and death (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Feature | N with Data | N (%)/Value ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 1598 | 41.3±14.5 |

| Gender (% female) | 1598 | 1111(69.5) |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 1598 | 1214(76.0) |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 1264 | 28.8±13.0 |

| Etiology of ALF | ||

| Acetaminophen | 1590 | 750(47.2) |

| ALF in pregnancy | 1590 | 13(0.8) |

| Autoimmune ALF | 1590 | 109(6.9) |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 1590 | 11(0.7) |

| Drug-Induced (idiosyncratic) | 1590 | 180(11.3) |

| Hepatitis A | 1590 | 31(1.9) |

| Hepatitis B (+/− delta) | 1590 | 116(7.3) |

| Hepatitis C | 1590 | 3(0.2) |

| Hepatitis E | 1590 | 3(0.2) |

| Mushroom Intoxication | 1590 | 11(0.7) |

| Shock/Ischemia | 1590 | 79(5.0) |

| Wilson Disease | 1590 | 18(1.1) |

| Indeterminate | 1590 | 190(11.9) |

| Other viruses | 1590 | 14(0.9) |

| Other Etiology | 1590 | 62(3.9) |

| SIRS on Admission | ||

| 0 | 1545 | 225(14.6) |

| 1 | 1545 | 475(30.7) |

| 2 | 1545 | 453(29.3) |

| 3 | 1545 | 313(20.3) |

| 4 | 1545 | 79(5.1) |

| Hepatic Encephalopathy Grade on Admission | ||

| 1 | 1570 | 407(25.9) |

| 2 | 1570 | 378(24.1) |

| 3 | 1570 | 333(21.2) |

| 4 | 1570 | 452(28.8) |

| Complications During First 7 Days after Admission | ||

| Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 1598 | 514(32.2) |

| Renal failure requiring RRT | 1598 | 532(33.3) |

| Infection | 1598 | 563(35.2) |

| Intracranial Pressure Monitor | 1598 | 224(14.0) |

| Outcome at 21 Days from Admission | ||

| Spontaneous Survival | 1598 | 752(47.1) |

| Liver Transplantation (LT) | 1598 | 390(24.4) |

| Death | ||

| All Deaths | 1598 | 517(32.4) |

| Death after LT | 390 | 61(15.6) |

A decline in platelet count after admission for ALF is associated with the SIRS, the development of MOSF, and poor outcome

Analysis of platelet values over time showed a decline in the adjusted mean platelet count in the overall study population from day 1 (165±20×109/L) to a nadir at day 5 (113±2×109/L), increasing slightly thereafter at day 7 (118±3×109/L) (data not shown). Patients with APAP- and non-APAP-induced ALF had a very similar magnitude of platelet count decline after admission (Supplementary Figure 2). As expected considering the characteristic early resolution of ALF due to APAP, the INR progressively declined after day 2. In contrast, the INR remained elevated and relatively unchanged after day 2 in patients with non-APAP-induced ALF.

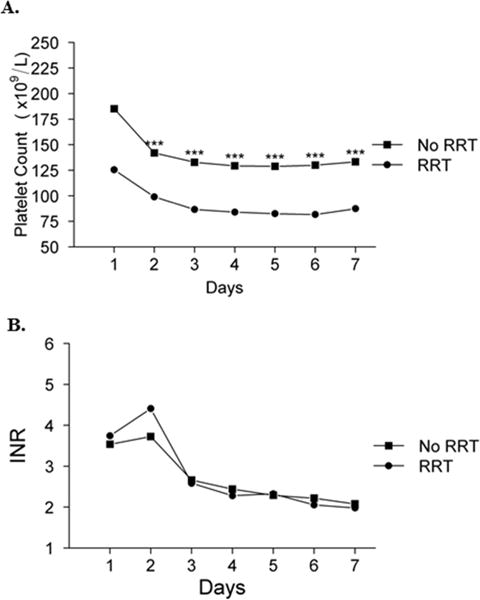

Although day 1 platelet counts were similar in patients with and without the SIRS on admission (182±27 vs. 146±30×109/L, respectively; P=0.38), the platelet count in patients with the SIRS declined dramatically from day 1 to day 2 (119±3×109/L), with a nadir at day 6 (103±3.20×109/L) (Figure 1a). In contrast, patients admitted without the SIRS maintained a relatively stable mean platelet count between days 1–7. Furthermore, platelet counts were significantly lower in patients with, compared to those without, the SIRS on each day between days 2–7 (P≤0.001). In contrast, the INR was significantly higher in patients with the SIRS only on day 1, but similar between the groups on all subsequent days after admission (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Platelet count (A) and INR (B) on days 1–7 according to the presence or absence of the SIRS on admission.

Presence of SIRS is defined as presence of at least 2 positive components. Mixed model estimates: ***p ≤0.001, **p ≤0.01, *p ≤0.05.

The grade of HE, which has been shown to be related to the presence of the SIRS, was also related to platelet count on days 2–7 after enrollment. As shown in Figure 2a, the mean platelet count in patients with high grade HE on admission declined to significantly lower levels on each day between days 2–7 than in patients with low grade HE (P ≤0.001). In contrast, the INR was not significantly different between the two groups after admission (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Platelet count (A) and INR (B) on days 1–7 according to the grade of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) on admission.

Mixed model estimates: ***p ≤0.001, **p ≤0.01, *p ≤0.05.

Previous studies have shown that certain admission blood chemistries reflect the onset of MOSF and predict poor outcome in patients with ALF, including the presence of acidosis and high lactate, phosphate, and creatinine. As depicted in Supplemental Figure 3, these laboratories also predict the magnitude of decline in platelet count after admission; patients with higher than normal admission lactate (>2.2mg/dl), creatinine (>1.2mg/dl), and phosphate (>4.6mg/dl), and lower than normal bicarbonate (≤21mg/dl), had significantly lower mean platelet counts on each day between days 2 and 7 compared to patients with normal admission laboratories (P≤0.001 for each laboratory, for each day).

The relationship between mean platelet count and development of systemic complications (MOSF) after admission for ALF was also explored (Figures 3 and 4). As depicted in Figure 3a, platelet counts in patients who required vasopressor support were significantly lower than in patients who did not on each day between days 2–7 (P≤0.001 for each day). In contrast, the INR was inconsistently higher in patients who required vasopressors than in those who did not (Figure 3b), and differences were very small notwithstanding intermittent statistical significance. Similarly, mean platelet count in patients who required RRT during days 1–7 were significantly lower than in patients who did not on each day between days 2–7 (P ≤0.001 for each day), despite the fact that many in the former group were likely to have been transfused platelets prior to insertion of a dialysis catheter (Figure 4a). In contrast, mean INR was not significantly different in patients who received or did not receive RRT between days 1–7 despite the probability that the former group received plasma transfusion for RRT catheter placement (Figure 4b). Finally, platelet counts in patients who had an ICP monitor placed between days 1–7 were also significantly lower than in those who did not on days 4–7 despite the probability of platelet transfusion in the former group prior to the insertion of the device. In contrast, there was no significant difference in INR between patients in whom an ICP monitor was, and was not, placed, despite the probability of plasma infusion in the former group (data not shown).

Figure 3. Platelet count (A) and INR (B) on days 1–7 according to the need for vasopressors.

Mixed model estimates: ***p ≤0.001, **p ≤0.01, *p ≤0.05.

Figure 4. Platelet count (A) and INR (B) on days 1–7 according to the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Mixed model estimates: ***p ≤0.001, **p ≤0.01, *p ≤0.05.

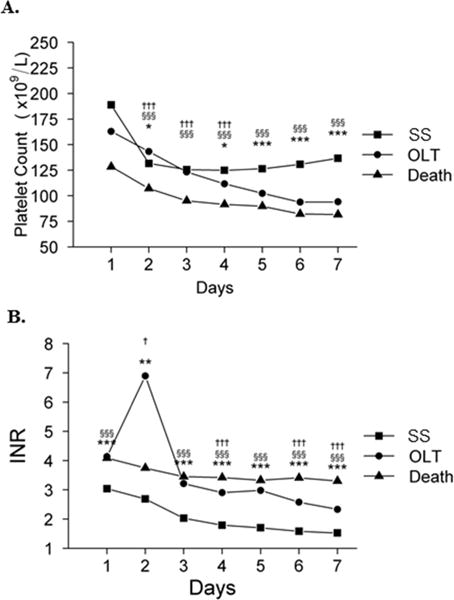

Platelet counts after admission also varied depending upon outcome at day 21 (Figure 5a). Although differences were not statistically significant on admission, mean platelet counts in spontaneous survivors were higher than patients who underwent LT, and were lowest in patients who died. Moreover, platelet counts in spontaneous survivors initially declined between days 1–2, but thereafter, began to recover (from 132 to 138 ×109/L between day 2–7). In contrast, platelet counts in patients who underwent LT or died declined progressively each day between days 1–7, with counts in LT recipients intermediate between spontaneous survivors and those who died. Platelet counts were significantly lower between days 2–7 in patients who died than in spontaneous survivors (P≤0.001 for each day), were significantly lower between days 2–4 in patients who died than in those transplanted (P≤0.001 for each day), and were significantly lower between days 5–7 in transplanted patients than spontaneous survivors (P≤0.001 for each day).

Figure 5. Platelet count (A) and INR (B) on days 1–7 according to outcome at Day 21.

Three symbols, p ≤0.001; two symbols, p ≤0.01; one symbol, p ≤0.05. *SS vs. LT, §SS vs. death, and †LT vs. death. (SS, spontaneous survival; LT, liver transplantation).

The trends in the INR over time according to outcome at day 21 were similar to the platelet counts in several respects. As seen in Figure 5b, mean INR improved daily from day 1–7 in spontaneous survivors. In contrast, mean INR remained relatively high and unchanged between days 1–7 in patients who died. The INR was significantly higher on day 1 and 3–7 in patients who died than in spontaneous survivors (P ≤0.001 for each day), and was intermediate on days 3–7 in LT recipients between spontaneous survivors and those who died.

As noted in Methods, some study patients received transfusion of platelets or plasma over days 1–7, which could have affected these results. Accordingly, the data were reanalyzed in statistical models including transfusion of platelets or plasma as a covariate. The reanalysis shows almost no change from the unadjusted results reported above (data not shown).

Discussion

The current study documents a relationship between a declining platelet count, the presence of the SIRS, development of MOSF, and outcome in patients with ALF. We have recently shown that plasma microparticles are primarily derived from platelets in patients with ALF, and increase in proportion to the intensity of the same clinical parameters15, suggesting that the SIRS drives platelets to generate microparticles, which in turn, play a role in the pathogenesis of the ALF syndrome. The potential role of platelet-derived microparticles in mediating ALF may include effects that are both pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic.

Precedence exists for a pro-inflammatory role of platelets in mediating other syndromes characterized by intense systemic inflammation. In severe sepsis, a syndrome with many similarities to ALF18, platelet-derived microparticles have been suggested to cause cardiovascular collapse by promoting systemic inflammation, and thereby MOSF, by mechanisms that involve loss of microvascular tone, peripheral tissue shunting and ischemia, and the activation of hemostasis within the microvasculature19. Similar to the work presented herein, a decline in platelet count after admission to the hospital with sepsis portends an ominous prognosis. The decline in platelets is a component of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score20, which has also been shown to predict outcome in ICU patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure, the syndrome of MOSF in patients with cirrhosis21. Moreover, in a general intensive care population of >1000 patients with inflammatory medical conditions other than liver disease, a decline in platelets after admission of >30% was an independent predictor of mortality11. In the current analysis, the association of the SIRS and MOSF was more highly associated with the decline in platelet count than with the increase in INR, but both were associated with prognosis, suggesting that these laboratory parameters may reflect different types of injury: INR, the extent of primary liver injury, and platelets, the severity of systemic inflammation secondary to liver injury.

Recent observations from our lab15,22–24 and others25,26 have suggested that, in a conceptual paradox to the high INR, patients with ALF often have hypercoagulability. The pro-thrombotic state of ALF is partially mediated through SIRS-mediated platelet activation, since maximal clot firmness in thromboelastography (TEG), primarily a function of platelets, increased in direct proportion to the severity of the SIRS22. SIRS-mediated platelet activation may thereby explain the development of thrombocytopenia by inducing the clearance of platelet remnants, as well as the increase in microparticles, which are liberated from platelets upon activation. Other potential mechanisms contribute to the pro-thrombotic state of ALF and are also driven by the SIRS. For example, levels of the platelet-adhesive protein, vonWillebrand Factor (VWF), are markedly elevated in patients with ALF compared to normal controls23, as are levels of Factor VIII22, presumably due to activation of endothelial cells by the SIRS. Thus, deficiencies in the number of platelets or in liver-derived, pro-hemostatic coagulation factors appear to be compensated by systemic inflammation that maintains hemostasis at or above normal balance. Finally, as noted above, increased platelet-derived microparticles in patients with ALF may over-compensate for thrombocytopenia, since their pro-thrombotic potential in tissue factor-dependent assays was nearly 40-fold higher than a control population of healthy subjects, higher than in any other pro-inflammatory state studied to date15.

A pro-thrombotic state is consistent with evidence of activation of intrahepatic hemostasis and peripheral tissue ischemia, both of which occur in patients with ALF. Evidence of activation of hemostasis (fibrin) has long been noted in liver biopsy specimens from patients with acetaminophen-induced ALF27, leading to an early trial of heparin to treat the disorder28. More recently, two studies have shown that administering heparin to mice with APAP-induced acute liver injury ameliorated the severity of hepatic necrosis1,29, and a third documented platelet sequestration within the necrotic liver (at the expense of peripheral platelet numbers) also contributes to liver injury30. These observations suggest that intra-sinusoidal activation of hemostasis may lead to a secondary ischemic injury. The recent observation that acute liver injury may de-encrypt hepatocyte-derived tissue factor31 provides a plausible mechanism by which such injury generates thrombin. In turn, thrombin generation may activate platelets and generate platelet microparticles; alternatively, platelet activation in patients with ALF might ensue via inflammatory mediators, which is perhaps more consistent with the data presented herein.

We acknowledge deficiencies in our data. First, due to drop-out from the ALFSG Registry from LT and death, the study population changes from day to day. This limitation has hampered our ability to identify a specific threshold predictive of poor outcome, and to analyze the data using competing risks Cox proportional hazard models. Second, the transfusion of platelets and/or plasma during days 1–7 could have affected our results. We believe the effect of transfusion was minimal, however, since only a small minority of subjects received platelet transfusions, the effects of transfusion on the INR and platelet counts were not discernable when patients who received transfusions were compared to those who did not (data not shown), and no significant effect was seen in our results using statistical models in which receipt of transfusions was included as a covariate.

We conclude that the platelet count after admission to the hospital conveys important information about the impending complications and outcome of a patient with ALF. A decreasing platelet count is a sign of systemic inflammation and the likelihood of developing serious systemic complications including high grade HE, cardiovascular collapse, and death or the need for LT. We hypothesize that the decrease in platelet count represents an integral event in the pathogenesis of the ALF syndrome rather than a non-specific marker of suppressed bone marrow production. Further studies will be needed to prove the pivotal role of platelets in mediating the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic features of the ALF syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Number of observations available for each day of follow-up.

Supplemental Figure 2. Platelet count and INR according to etiology of ALF (acetaminophen vs. non-acetaminophen).

Supplemental Figure 3. Platelet count on Days 1–7 according to admission laboratories.

Supplemental Table 1. Clinical characteristics according to the presence of SIRS on admission.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/NIDDK Grant #U-01 DK-58369.

Abbreviations

- ALF

acute liver failure

- SIRS

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- MOSF

multi-organ system failure

- LT

liver transplantation

- RRT

renal replacement therapy

- INR

International Normalized Ratio of the prothrombin time

- ALFSG

ALF Study Group

- WBC

white blood cell count

- APAP

acetaminophen (paracetamol)

- ICP

intracranial pressure

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score

- ICU

intensive care unit

- TEG

thromboelastography

- VWF

von Willebrand Factor

- ADAMTS-13

a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type-1 motifs 13

- ARDS

adult respiratory response syndrome

- DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

- SS

spontaneous survival

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Author’s Contributions: R. Todd Stravitz: concept and design of study, primary author of manuscript; C. Ellerbe and D. Durkalski: data acquisition and statistical analysis; A. Reuben, T. Lisman, and W.M. Lee: scientific and manuscript review.

Prior presentation. These data were presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (Plenary Session).

References

- 1.Ganey PE, Luyendyk JP, Newport SW, et al. Role of the coagulation system in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Hepatology. 2007;46:1177–1186. doi: 10.1002/hep.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison PM, Wendon JA, Gimson AE, et al. Improvement by acetylcysteine of hemodynamics and oxygen transport in fulminant hepatic failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1852–1857. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106273242604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolando N, Wade J, Davalos M, et al. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2000;32:734–739. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemmesen JO, Larsen FS, Kondrup J, et al. Cerebral herniation in patients with acute liver failure is correlated with arterial ammonia concentration. Hepatology. 1999;29:648–653. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal W, Donaldson N, Wyncoll D, Wendon J. Blood lactate as an early predictor of outcome in paracetamol-induced acute liver failure: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:558–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K. Serum phosphate is an early predictor of outcome in severe acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2002;36:659–665. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz JN, Kolappa KP, Becker RC. Beyond thrombosis: the versatile platelet in critical illness. Chest. 2011;139:658–668. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Yang F, Dunn S, et al. Platelets as immune mediators: their role in host defense responses and sepsis. Thromb Res. 2011;127:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nijsten MW, ten Duis HJ, Zijlstra JG, et al. Blunted rise in platelet count in critically ill patients is associated with worse outcome. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3843–3846. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200012000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreau D, Timsit JF, Vesin A, et al. Platelet count decline: an early prognostic marker in critically ill patients with prolonged ICU stays. Chest. 2007;131:1735–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth SS, McEver RP, Weyrich AS, et al. Platelet functions beyond hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1759–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siljander PR. Platelet-derived microparticles - an updated perspective. Thromb Res. 2011;127:S30–S33. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(10)70152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiodt FV, Balko J, Schilsky M, et al. Thrombopoietin in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2003;37:558–561. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stravitz RT, Bowling R, Bradford RL, et al. Role of procoagulant microparticles in mediating complications and outcome of acute liver injury/acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2013;58:304–313. doi: 10.1002/hep.26307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trey C, Davidson C. The management of of fulminant hepatic failure. Progress in Liver Dis. 1970;3:282–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer DJ, Canabal JM, Arasi LC. Application of intensive care medicine principles in the management of the acute liver failure patient. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:S85–S89. doi: 10.1002/lt.21649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meziani F, Delabranche X, Asfar P, Toti F. Bench-to-bedside review: circulating microparticles–a new player in sepsis? Crit Care. 2010;14:236. doi: 10.1186/cc9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wehler M, Kokoska J, Reulbach U, et al. Short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with cirrhosis assessed by prognostic scoring systems. Hepatology. 2001;34:255–261. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stravitz RT, Lisman T, Luketic VA, et al. Minimal effects of acute liver injury/acute liver failure on hemostasis as assessed by thromboelastography. J Hepatol. 2012;56:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hugenholtz GC, Adelmeijer J, Meijers JC, et al. An unbalance between von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 in acute liver failure: implications for hemostasis and clinical outcome. Hepatology. 2013;58:752–761. doi: 10.1002/hep.26372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lisman T, Bakhtiari K, Adelmeijer J, et al. Intact thrombin generation and decreased fibrinolytic capacity in patients with acute liver injury or acute liver failure. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1312–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habib M, Roberts LN, Patel RK, et al. Evidence of rebalanced coagulation in acute liver injury and acute liver failure as measured by thrombin generation. Liver Int. 2013 Oct 27; doi: 10.1111/liv.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal B, Wright G, Gatt A, et al. Evaluation of coagulation abnormalities in acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012;57:780–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillenbrand P, Parbhoo SP, Jedrychowski A, Sherlock S. Significance of intravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis in acute hepatic failure. Gut. 1974;15:83–88. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gazzard BG, Clark R, Borirakchanyavat V, Williams R. A controlled trial of heparin therapy in the coagulation defect of paracetamol-induced hepatic necrosis. Gut. 1974;15:89–93. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weerasinghe SV, Moons DS, Altshuler PJ, et al. Fibrinogen-gamma proteolysis and solubility dynamics during apoptotic mouse liver injury: heparin prevents and treats liver damage. Hepatology. 2011;53:1323–1332. doi: 10.1002/hep.24203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyakawa K, Joshi N, Sullivan BP, et al. Platelets and protease-activated receptor-4 contribute to acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Blood. 2015 doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-598656. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan BP, Kopec AK, Joshi N, et al. Hepatocyte tissue factor activates the coagulation cascade in mice. Blood. 2013;121:1868–1874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Number of observations available for each day of follow-up.

Supplemental Figure 2. Platelet count and INR according to etiology of ALF (acetaminophen vs. non-acetaminophen).

Supplemental Figure 3. Platelet count on Days 1–7 according to admission laboratories.

Supplemental Table 1. Clinical characteristics according to the presence of SIRS on admission.