Abstract

The present study extends an earlier report that retinoic acid (RA) down-regulates IgE Ab synthesis in vitro. Here, we show the suppressive activity of RA on IgE production in vivo and its underlying mechanisms. We found that RA down-regulated IgE class switching recombination (CSR) mainly through RA receptor α (RARα). Additionally, RA inhibited histone acetylation of germ-line ε (GLε) promoter, leading to suppression of IgE CSR. Consistently, serum IgE levels were substantially elevated in vitamin A-deficient (VAD) mice and this was more dramatic in VAD-lecithin:retinol acyltransferase deficient (LRAT−/−) mice. Further, serum mouse mast cell protease-1 (mMCP-1) level was elevated while frequency of intestinal regulatory T cells (Tregs) were diminished in VAD LRAT−/− mice, reflecting that deprivation of RA leads to allergic immune response. Taken together, our results reveal that RA has an IgE-repressive activity in vivo, which may ameliorate IgE-mediated allergic disease.

Keywords: CSR, IgE, food allergy, retinoic acid, RARα, vitamin A deficient mice

1. Introduction

IgE antibody is a key mediator of allergic diseases. It is well established that IgE class switch recombination (CSR) is stimulated by IL-4 [1]. Ig CSR requires germ-line (GL) transcription through target S regions [2] and expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) [3, 4]. CSR is directed to a particular constant region of heavy chain (CH) gene by cytokines that induce transcription from GL CH genes before switch recombination to the same CH gene [2].

Retinoic acid (RA), a vitamin A metabolite, plays an important role in the regulation of mucosal immunity. RA is synthesized from its precursor molecules such as retinol in gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT)-dendritic cells (DCs) [5]. RA promotes Foxp3+ Tregs differentiation [6–8] while inhibits Th17 differentiation through inhibiting the expression of RORγt, a canonical Th17 transcriptional factor [9, 10]. In addition, RA is relevant to differentiation and migration of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). Thus, vitamin A deficiency dramatically expands ILC2 and suppress ILC3 in the gut, and RA differentially regulates the migration of ILC subsets to the gut [11, 12]. We have recently demonstrated that RA alone can enhance IgA CSR and that this activity of RA is more selective than that of TGF-β1 [13]. Related to the IgE response, RA inhibits IL-4-induced IgE expression by murine and human B cells in vitro [14, 15]. Nevertheless, it is virtually unknown if RA has such activity in vivo and its underlying mechanism. In this study, we found that RA acts a negative regulator of IgE production in mice and that RA represses IgE CSR mainly through RA receptor α (RARα) and maintaining RAR corepressor.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

C57BL/6 mice were purchased and maintained in an animal environmental control chamber from Daehan biolink. Co. Ltd (Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea). Animals were fed Purina Laboratory Rodent Chow 5001 ad libitum. Animal care was performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines set forth by Kangwon National University. Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase deficient (LRAT−/−) mice [16] were provided by Dr. J. Rodrigo Mora (Harvard Medical School, USA) [17].

2.2. Preparation and characterization of vitamin A-deficient (VAD) mice

To produce vitamin A-deficient mice (VAD), the mice were bred, and gravid females received either a diet that lacked vitamin A (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan) or a regular diet containing retinyl acetate. These diets started at 7–10 days of gestation. The pups were weaned at 4 weeks of age and maintained on the same diet over 12 weeks of age [5]. Vitamin A deficiency was confirmed by analyzing the levels of fecal IgA [18] or serum retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) [19]. Serum mMCP-1 level was determined using ELISA kit (eBioscience). For regulatory T cells (Treg) analysis, cells were isolated and stained as described [20].

2.3. B cell preparations and culture

Mouse spleen B cells were prepared as previously described [13]. CD43− resting B cells were purified using anti-mouse CD43-conjugated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, CA). A total of 0.25 ~ 2× 105 B cells/well were cultured in flat-bottomed, 96-well tissue culture plates in a volume of 200 µl complete medium with LPS in the presence or absence of retinoic acid, IL-4, LE540, and/or AM80.

2.4. Reagents

RA, IL-4, and LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. AM80 and LE540 were purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). The antibodies used in ELISA and anti-histone H3 Ab were purchased from Southern Biotechnology and Santa Cruze, respectively.

2.5. Isotype-specific ELISA

ELISA was performed as described previously[21]. The reaction products were measured at 415 nm with an ELISA reader (iMark™ Microplate Absorbance Reader, Bio-Rad). For the detection of IgA retained in fecal pellets were diluted in PBS, centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min, and supernatants collected.CA). For IgE ELISA, plates were coated with purified rat anti-mouse IgE (R35–72, BD Pharmingen) overnight at 4°C, and blocked for 1 h with 3% BSA-PBS. Standard mouse IgE and culture supernatants incubated for 1 h, and antibodies were detected with biotin rat anti-mouse IgE (R35–118, BD Pharmingen) and streptavidin-HRP using a mouse IgE standard (BD Biosciences).

2.6. RNA preparation and RT-PCR

RNA preparation, reverse transcription, and PCR were performed as described previously [21]. Sense/antisense primers of GLTα and β-actin were the same as described before [21]. GLTε sense, 5’-ACT AGA GAT TCA CAA CG-3’, and antisense, 5’-AGC GAT GAA TGG AGT AGC-3’ were purchased from Bioneer (Seoul, Korea).

2.7. Transfection and Luciferase assay

GLε-Luc reporter plasmid was provided by Dr. J. Stavnezer (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA)[22]. CH12F3.2A B lymphoma cells (provided by Dr. T. Honjo, Osaka University, Japan, [31]) were transfected by electroporation with a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad, CA) as previously described [21]. Reporter plasmids were cotransfected with expression plasmids and pCMVβgal (Stratagene) and luciferase and β-gal assays were performed as described [21].

2.8. ChIP assay

This was performed using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology). The primer sequences were the following: pGLε promoter region, forward, 5-GTG TCT CCT AGA AAG AGG CCT CAC-3, and reverse, 5- TGT GCA GGC TCC CCA GGC GTT GTG-3, and the products were resolved by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between experimental groups were determined by ANOVAs, and values of P < 0.05 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test were considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Inhibitory effect of RA on IL4-induced IgE secretion and B cell growth

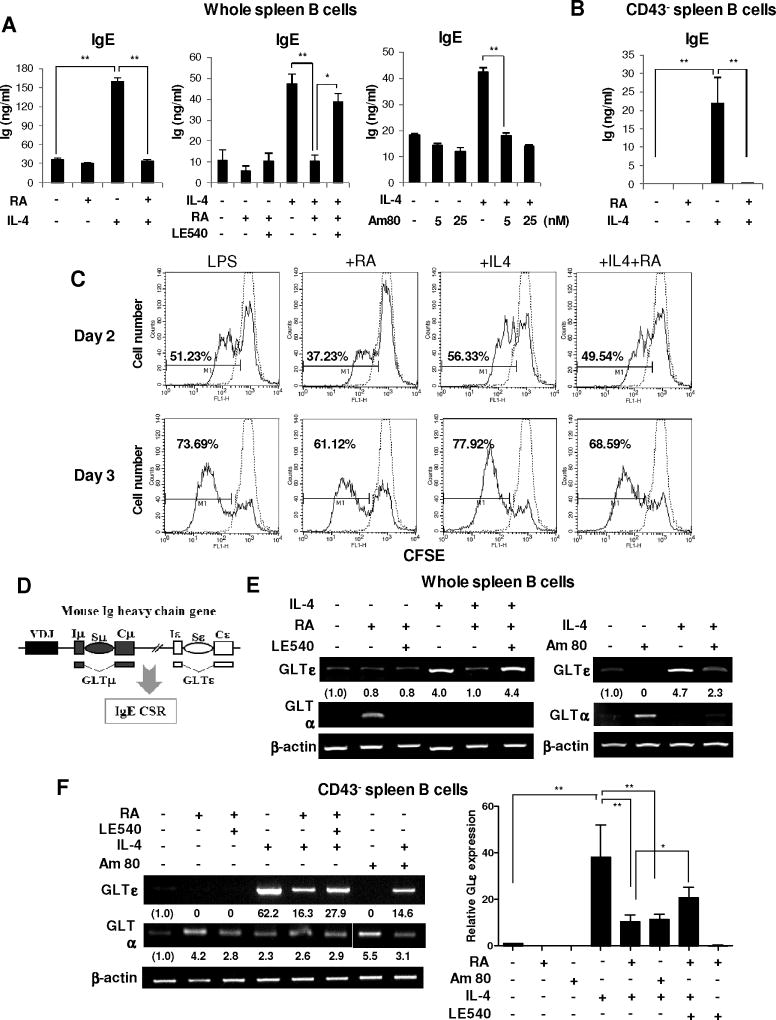

We first determined the mechanisms by which RA decreases IgE production. We adopted in vitro system in which IgE production is stimulated by IL-4 as well documented in humans and mice [14, 15]. Since IgE production in vitro is known to be dependent on cell density[23], we examined the effect of RA on IL4-induced IgE production by different densities of B cells. RA completely abrogated the IL4-induced IgE production by B cells (2×105) (Fig. 1A, B) and by lower densities of B cells (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). It was conceivable that the decrease of IgE production by RA is simply due to the anti-proliferative activity of RA. However, CFSE assay revealed that RA slightly decreased B cell proliferation in the presence of IL-4 at high and low densities of B cells (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 1C), indicating that anti-proliferative activity of RA is marginal in the suppression of IgE production and that this suppression of IgE by RA is mostly attributable to its effect on B cell differentiation.

Fig. 1. Effect of RA on IL4-Induced IgE expression and B cell proliferation.

(A, B) Whole splenic B cells (panel A) and resting splenic CD43− B cells (2 × 105) (panel B) from BALB/c mice were cultured with LPS (12.5 µg/ml), RA (25 nM), IL-4 (10 ng/ml), LE540 (3 µM), and Am80 as indicated. After 7 days of culture, Ig production was determined by ELISA. (C) Cell proliferation was assessed after 48 h and 72 h analyzing the dilution of CFSE in the same number of viable cells. Dotted line indicates CFSE-labeled unstimulated B cells at day 0. (D) A diagram of DNA recombination events occurring during switching to IgE. RNA transcripts are indicated beneath the DNA diagrams. (E, F) Culture conditions were the same as in panel A. After 2 days of culture, levels of GLTs and β-actin were measured by RT-PCR. The graphs show relative GLTε cDNA levels normalized to the expression of β-actin cDNA by ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) analysis. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (mean±SEM) *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

3.2. Molecular characterization of the suppressive activity of RA

RA transduce its signal mostly through binding to a heterodimer of nuclear receptors, RARs and retinoid X receptors (RXRs) [24, 25]. To verify the specific activity of RA, AM80 (a RARα agonist) and LE540 (a RAR antagonist) were tested. LE540 blocked the RA-induced IgE suppression, whereas AM80 suppressed the IL4-induced IgE production (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that RA down-regulates IgE production primarily through RAR.

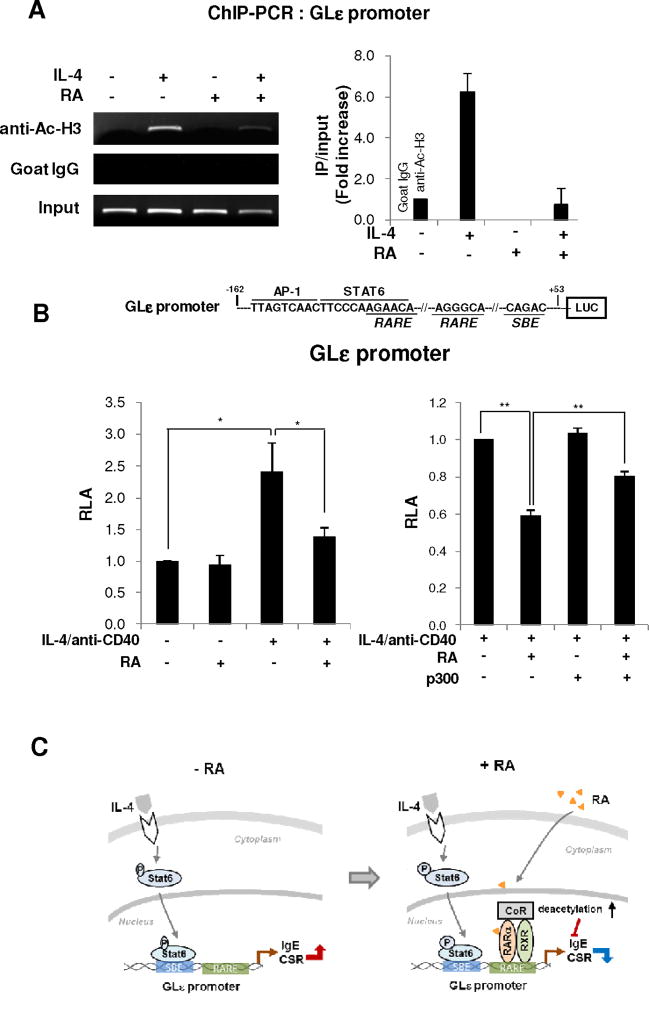

Transcription of unrearranged Cε gene to produce germ-line transcript ε (GLTε) precedes CSR to IgE (Fig. 1D). Therefore, expression of GLTε is used to indicate active IgE CSR. Expression of GLTε was increased by IL-4 and this increase was virtually abolished by RA. Again, LE540 blocked the RA-induced GLTε suppression and AM80 suppressed the IL4-induced GLTε expression. Here, expression patterns of GLTα were sharply contrasted to those of GLTε (Fig. 1E, F). These results suggest that RA specifically downregulates IgE CSR mainly through RAR. Chromatin acetylation is generally associated with transcriptional activation. Several histone acetyltransferases (HATs) including p300 have been identified as transcription coactivators while corepressor HDACs are considered to repress/inhibit transcription by associating with gene promoters [26]. RAR is associated with co-activator interacting domain (CoA-ID) and corepressor ID (CoR-ID) [27] and acetyl-histone H3 (Ac-H3) and Ac-H4 are strongly correlated with GLT expression [28]. We therefore examined the effect of RA on the histone acetylation of GLε promoter using ChIP assay. IL-4 increased histone acetylation of GLε promoter and this increase was abolished by RA (Fig. 2A). We also examined the effect of RA on GLε promoter activity. IL-4/ CD40-induced GLε promoter activity was inhibited by RA (Fig. 2B, left panel). Subsequently, we assessed whether inhibitory effect of RA is affected by p300 (a histone acetyltransferase). In fact, the inhibitory activity of RA on GLε promoter was partially blocked by overexpressed p300 (Fig. 2B, right panel). These results suggest that RA inhibits histone acetylation of GLε promoter, leading to suppression of IgE CSR.

Fig. 2. Analyses of GLε promoter activity.

(A) ChIP assay for acetylated histone H3 to GLε promoter. Spleen B cells (2 × 107) from BALB/c mice were cultured with LPS (12.5 µg/ml), RA (25 nM), and IL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 48 h. Soluble chromatin was immunoprecipitated with control (irrelevant goat IgG) or anti-acetylated histone H3 Ab (10 µg/ml). PCR primers for the regions of the GLε promoter gene were used to amplify the DNA isolated from the immunoprecipitated chromatin. The value is normalized for the expression level of the inputs. (B) Effect of p300 on GLε promoter activity. Two putative retinoic acid response element (RARE) (PuG(G/T)TCA [23]) were identified using two software, TFSEARCH Ver 1.3 (Parallel Application TRC Lab., RWCP, Japan) and MatInspector Ver 3.0 (Genomatix Software). CH12F3-2A B lymphoma cells (1.2 × 107) were transfected with GLε-Luc (−162/+53) reporter (15 µg) and p300 (10 µg). RA (10 µM), IL-4 (10 ng/ml), and anti-CD40 Ab (10 ng/ml) was added, and luciferase activities measured 16 h later. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (mean±SEM) *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. (C) Proposed mechanisms by which RA suppresses IL4-induced IgE expression.

3.3. RA contributes to suppression of IgE production in vivo

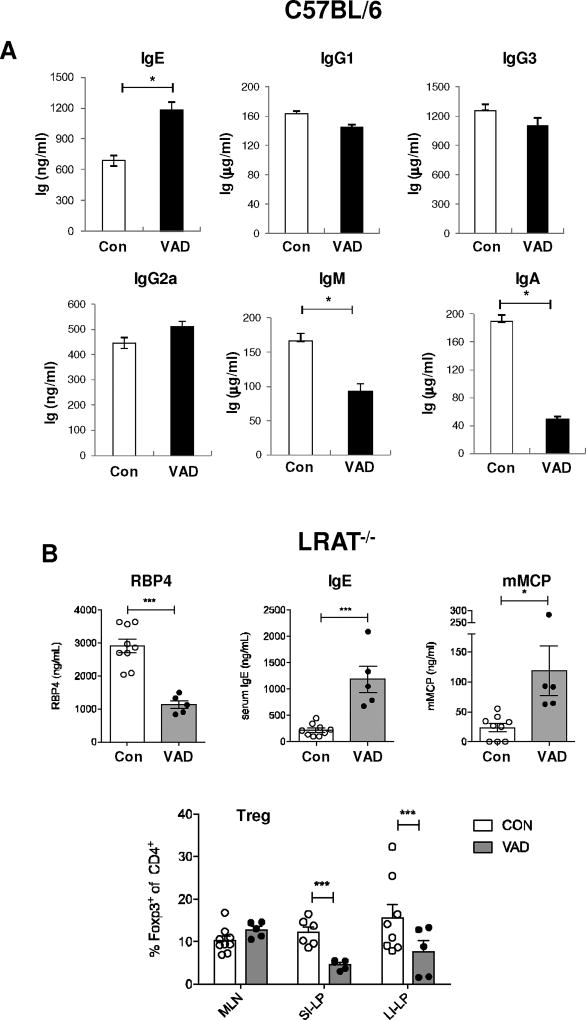

We assessed whether RA is physiologically relevant by investigating the role of RA in IgE production in vitamin A-deficient (VAD) mice. In VAD mice, serum IgE levels were elevated by 2-fold, while levels of other isotypes were little changed (IgG1, IgG3, and IgG2b) and decreased (IgM and IgA) (Fig. 3A). Not shown, the amount of fecal IgA was decreased in VAD mice as shown before [13]. We also examined the effect of RA in lecithin:retinol acyltransferase deficient (LRAT−/−) mice because it is difficult to deplete vitamin A completely in WT mice. As expected, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) expression was substantially diminished, indicating that RA is not retained in this mice. The increase of serum IgE level was more dramatic in VAD LRAT−/− mice (Fig. 3B), suggesting that RA down-regulates IgE production in vivo. Furthermore, in VAD LRAT−/− mice, serum level of mouse mast cell protease-1 (mMCP-1) which plays a role in the induction of allergic response [29] was elevated (Fig. 3B). In contrast, frequency of intestinal Tregs, which are involved in the control of the food allergy [30], was diminished as shown in Fig. 3B. These results suggest that RA inhibits allergic response by downregulating IgE/mast cell response, which is possibly attributed in part to the induction of Tregs differentiation by RA [6–8]. Recently, it has been shown that RA-skewed DC can reduce allergen-specific IgE level and anaphylactic responses [31]. Thus, RA can contribute to control of allergic response at the multiple steps including the direct effect on B cells.

Fig. 3. Immunological and physiological changes in vitamin A-deficient (VAD) mice.

(A) Serum Ig levels were measured by ELISA in WT C57BL/6. Data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples with five mice per group. (B) Serum levels of RPB4, IgE and mMCP were measured by ELISA in LRAT−/− mice. Proportion of Foxp3+ Tregs among CD4+ T cells in the mensentric lymph node (MLN), the small intestine laminar proplia (SI-LP) and large intestine LP (LI-LP) of control diet LRAT−/− (open circle) and VAD LRAT−/− (closed circle) mice. (n = 9~13 mice per group). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

4. Concluding Remarks

In the present study, we found that IgE suppressive activity of RA is possible mainly through RAR and maintaining RAR corepressor as proposed in Fig. 2C. We demonstrate that RA has an IgE-repressive activity in vivo. Vitamin A is abundant in colostrum and milk [32] and it is converted to RA in the mucosal tissue [5]. Thus, it is highly plausible that RA plays a pivotal role in maintaining mucosal homeostasis by down-regulating IgE level in newborns and post-weaning life as well.

Supplementary Material

Hightlights.

-

-

RA represses IgE CSR through RA receptor alpha (RARα).

-

-

RA inhibits histone acetylation of Ig germ-line ε (GLε) promoter.

-

-

RA has an IgE-repressive activity in vivo, which may ameliorate IgE-mediated allergic disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mi-Na Kweon (Ulsan Univ., Seoul, South Korea) and Sun-Young Chang (Ajou Univ., Suwon, South Korea) for their valuable advice on the VAD mice model. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2013R1A1A2057931 to GY.S. and 2016R1A4A1010115 to PH.K.), 2014 Research Grant from Kangwon National University (C1010721-01-01) and US National Institutes of Health Grants (R01 AI106302 to C.R.N.).

Abbreviations

- AID

activation-induced cytidine deaminase

- CSR

class switch recombination

- GALT

gut-associated lymphoid tissues

- GLε

germ-line ε

- GLT

Ig germ-line transcript

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- LRAT−/−

lecithin:retinol acyltransferase deficient

- MCP-1

mast cell protease-1

- RA

retinoic acid

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- RBP4

retinol binding protein 4

- VAD

vitamin A-deficient

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Honjo T, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. Molecular mechanism of class switch recombination: linkage with somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:165–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.090501.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stavnezer J. Molecular processes that regulate class switching. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;245:127–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59641-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Z, Zan H, Pone EJ, Mai T, Casali P. Immunoglobulin class-switch DNA recombination: induction, targeting and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:517–531. doi: 10.1038/nri3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, Belkaid Y. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CC, Esterhazy D, Sarde A, London M, Pullabhatla V, Osma-Garcia I, Al-Bader R, Ortiz C, Elgueta R, Arno M, de Rinaldis E, Mucida D, Lord GM, Noelle RJ. Retinoic acid is essential for Th1 cell lineage stability and prevents transition to a Th17 cell program. Immunity. 2015;42:499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer SP, Wilhelm C, Yang Q, Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Boyd A, Nutman TB, Urban JF, Jr, Wang J, Ramalingam TR, Bhandoola A, Wynn TA, Belkaid Y. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science. 2014;343:432–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1247606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MH, Taparowsky EJ, Kim CH. Retinoic Acid Differentially Regulates the Migration of Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets to the Gut. Immunity. 2015;43:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo GY, Jang YS, Kim HA, Lee MR, Park MH, Park SR, Lee JM, Choe J, Kim PH. Retinoic acid, acting as a highly specific IgA isotype switch factor, cooperates with TGF-beta1 to enhance the overall IgA response. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:325–335. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokuyama H, Tokuyama Y, Nakanishi K. Retinoids inhibit IL-4-dependent IgE and IgG1 production by LPS-stimulated murine splenic B cells. Cell Immunol. 1995;162:153–158. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worm M, Krah JM, Manz RA, Henz BM. Retinoic acid inhibits CD40 + interleukin-4-mediated IgE production in vitro. Blood. 1998;92:1713–1720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Byrne SM, Wongsiriroj N, Libien J, Vogel S, Goldberg IJ, Baehr W, Palczewski K, Blaner WS. Retinoid absorption and storage is impaired in mice lacking lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35647–35657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507924200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villablanca EJ, Wang S, de Calisto J, Gomes DC, Kane MA, Napoli JL, Blaner WS, Kagechika H, Blomhoff R, Rosemblatt M, Bono MR, von Andrian UH, Mora JR. MyD88 and retinoic acid signaling pathways interact to modulate gastrointestinal activities of dendritic cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:176–185. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mora JR, Iwata M, Eksteen B, Song SY, Junt T, Senman B, Otipoby KL, Yokota A, Takeuchi H, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Rajewsky K, Adams DH, von Andrian UH. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaensson-Gyllenback E, Kotarsky K, Zapata F, Persson EK, Gundersen TE, Blomhoff R, Agace WW. Bile retinoids imprint intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells with the ability to generate gut-tropic T cells. Mucosal immunology. 2011;4:438–447. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefka AT, Feehley T, Tripathi P, Qiu J, McCoy K, Mazmanian SK, Tjota MY, Seo GY, Cao S, Theriault BR, Antonopoulos DA, Zhou L, Chang EB, Fu YX, Nagler CR. Commensal bacteria protect against food allergen sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13145–13150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412008111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SR, Lee JH, Kim PH. Smad3 and Smad4 mediate transforming growth factor-beta1-induced IgA expression in murine B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1706–1715. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1706::aid-immu1706>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delphin S, Stavnezer J. Characterization of an interleukin 4 (IL-4) responsive region in the immunoglobulin heavy chain germline epsilon promoter: regulation by NF-IL-4, a C/EBP family member and NF-kappa B/p50. J Exp Med. 1995;181:181–192. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabah D, Conrad DH. Effect of cell density on in vitro mouse immunoglobulin E production. Immunology. 2002;106:503–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastien J, Rochette-Egly C. Nuclear retinoid receptors and the transcription of retinoid-target genes. Gene. 2004;328:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebvre P, Martin PJ, Flajollet S, Dedieu S, Billaut X, Lefebvre B. Transcriptional activities of retinoic acid receptors. Vitam Horm. 2005;70:199–264. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)70007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Germain P, Iyer J, Zechel C, Gronemeyer H. Co-regulator recruitment and the mechanism of retinoic acid receptor synergy. Nature. 2002;415:187–192. doi: 10.1038/415187a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Whang N, Wuerffel R, Kenter AL. AID-dependent histone acetylation is detected in immunoglobulin S regions. J Exp Med. 2006;203:215–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forbes EE, Groschwitz K, Abonia JP, Brandt EB, Cohen E, Blanchard C, Ahrens R, Seidu L, McKenzie A, Strait R, Finkelman FD, Foster PS, Matthaei KI, Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. IL-9- and mast cell-mediated intestinal permeability predisposes to oral antigen hypersensitivity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:897–913. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noval Rivas M, Chatila TA. Regulatory T cells in allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:639–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawicki W, Li C, Town J, Zhang X, Gordon JR. Therapeutic reversal of food allergen sensitivity by mature retinoic acid-differentiated dendritic cell induction of LAG3+CD49b-Foxp3- regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1608–1620. e1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haskell MJ, Brown KH. Maternal vitamin A nutriture and the vitamin A content of human milk. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 1999;4:243–257. doi: 10.1023/a:1018745812512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.