Abstract

Background & Aims

Oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment offer new hope to both pre- and post-liver transplant (LT) patients. However, whether to treat HCV patients pre- versus post-LT is not clear, as treatment can improve liver function but could reduce the chance of receiving a LT while on the waiting list. Our objective was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment with oral DAAs in decompensated cirrhotic patients on the LT waiting list.

Methods

We used a validated mathematical model that simulated a virtual trial comparing long-term clinical and cost outcomes of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment with oral DAAs. Model parameters were estimated from United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data, SOLAR-1 and 2 trials, and published studies. For each strategy, we estimated the quality-adjusted life year (QALY), life expectancy, cost, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Results

For lower MELD scores, QALYs were higher with pre-LT HCV treatment compared to post-LT treatment. Pre-LT HCV treatment was cost-saving in patients with MELD ≤15, and cost-effective in patients with MELD 16–21. In contrast, post-LT HCV treatment was cost-effective in patients with MELD 22–29 and cost-saving if MELD ≥30. Results varied by drug prices and by UNOS regions.

Conclusions

For cirrhotic patients awaiting LT, pre-LT HCV treatment with DAAs is cost-effective/saving in patients with MELD≤21, whereas post-LT HCV treatment is cost-effective/saving in patients with MELD≥22.

Keywords: simulation model, sofosbuvir, health economics

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma and the leading indication for liver transplantation (LT) in the United States and Europe (1). About 15–20% of patients with HCV-related cirrhosis advance to decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma within 10 years (1). For these patients, mortality rates increase to approximately 15–20% per year, and liver transplant becomes the only viable option for long term survival (2).

Historically, treatment of HCV patients with decompensated cirrhosis who were candidates for LT or who underwent LT had been challenging because of the low efficacy and tolerability of interferon-based therapies (3). However, with the availability of oral direct-acting antivirals (DAA), HCV treatment can now be offered with high success rates, in both the pre and post-LT settings (4).

Despite the clear benefits of DAAs, the optimal timing of HCV treatment—pre LT versus post-LT, is not clear (2, 5). There is a trade-off—pre-LT HCV treatment can improve patients’ Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and reduce mortality while on the waiting list; however, it may also delay LT by decreasing patients’ priority on the waiting list. This situation has been termed “MELD limbo” or “MELD purgatory” (5). Furthermore, by eradicating HCV before transplant, some patients would no longer be eligible to receive an HCV-positive liver, which could further reduce their chance of getting a transplant. On the other hand, for some patients, not receiving pre-LT HCV treatment and waiting until LT could result in worsening of the underlying liver condition and increasing mortality on the waiting list. Such trade-offs need to be balanced to optimize patient outcomes.

In addition, the decision regarding the optimal time to treat HCV should take into account limited monetary resources. The high price of DAAs has created concerns about their impact on health care budgets, delaying timely treatment for many HCV patients, and has led to a debate about the value and affordability of these drugs (6). Three recent studies addressed this topic but reached conflicting conclusions—two concluded that pre-LT HCV treatment is always cost-effective (7, 8), whereas another study concluded that pre-LT HCV treatment is cost-effective if patients’ MELD score ≤25 and post-LT treatment is cost-effective if MELD>25 (9). Therefore, the objective of our study was to generate evidence for the optimal timing of HCV treatment by determining the cost-effectiveness of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment with approved oral DAAs in decompensated cirrhotic patients on the waiting list.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model Overview

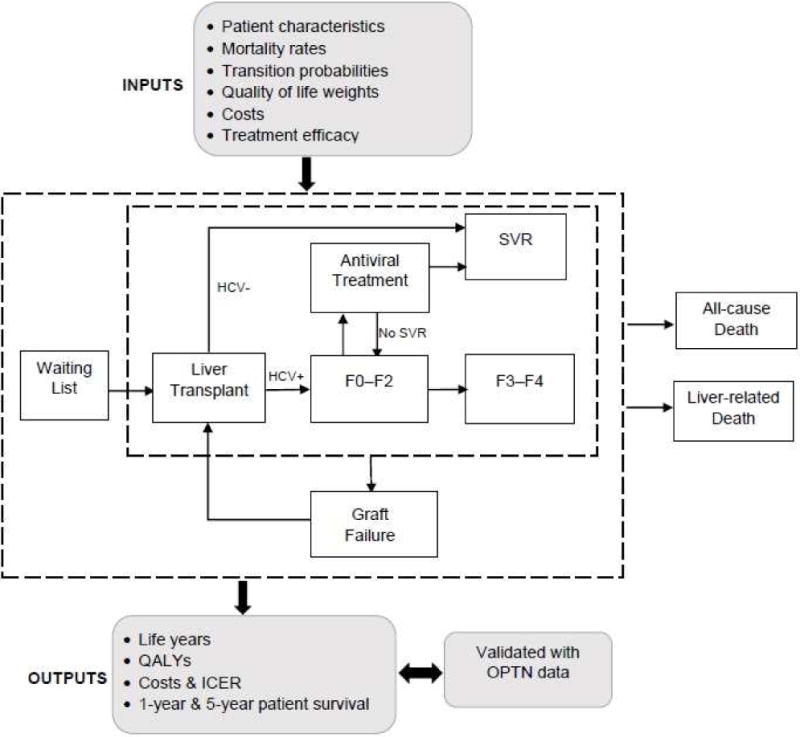

We used a validated individual-level state-transition model, SIM-LT (simulation of liver transplant candidates), that simulated a virtual trial comparing long-term outcomes of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment with oral DAAs (10). The model simulated the lifetime course of patients on the transplant waiting list and after LT (Figure 1). The model’s outcomes were validated using data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). In this analysis, we extended that model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment. We used a weekly cycle to advance time in the model and simulated 1 million patients to reduce simulation noise.

Figure 1. Model schematic showing the flow of patients pre- and post-liver transplantation (LT).

For each patient profile, the model simulated two treatment strategies: (1) pre-LT HCV treatment with DAAs, and (2) post-LT HCV treatment with DAAs.

Baseline population

We simulated patients with decompensated cirrhosis (without HCC) having HCV genotypes 1 or 4. The mean age of patients in the model was 50 and their MELD scores were in the range of 10–40.

Interventions

For each patient, we simulated two scenarios: 1) HCV treatment before LT (pre-LT treatment), and 2) HCV treatment after LT (post-LT treatment). Patients were treated with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir plus ribavirin for up to 12 weeks. The sustained virologic response (SVR) rates of sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir for pre-LT and post-LT were derived from the SOLAR-1 and SOLAR-2 studies (11–13).

In pre-LT treatment, HCV patients were treated while on the waiting list. If a patient underwent LT after less than 6 weeks of antiviral therapy, the treatment was assumed to be incomplete. On the other hand, if patients received at least 6 weeks of antiviral therapy before the transplant, we assumed that the treatment was complete and patients could achieve SVR. Our assumption was based on data from Curry et al. that reported that 93% of patients by week 4 of their treatment had undetectable HCV RNA, and among those who remained HCV RNA negative for 4 weeks or longer at the time of LT and cessation of antiviral therapy, only 1/26 experienced post-LT recurrence of viremia (4). The SVR rate for pre-LT treatment was 84%, as reported by the SOLAR-1 and SOLAR-2 studies (11–13). If patients failed to achieve SVR, they were retreated three months after LT. We selected the 3-month window as a time point that was sufficiently distanced from LT to minimize any perturbations of the immediate post-LT period but sufficiently early before progressive allograft disease could develop. Patients’ MELD score was adjusted according to their SVR status after the treatment.

In post-LT treatment, patients were not treated until after the LT. Patients’ MELD score could change while on the waiting list. All patients were offered HCV treatment three months after LT. The SVR rate for post-LT treatment was 95%, as reported by SOLAR-1 and SOLAR-2 studies (11–13). We varied the SVR rates in the sensitivity analysis. For both strategies, patients were treated only once after the transplant.

Disease Progression

While on the waiting list, patients’ MELD scores could increase, decrease or remain the same. Based on their MELD score, patients could undergo LT or die either because of liver-related or all-cause mortality. If patients were treated on the waiting list, we determined patients’ SVR status four weeks after the treatment ended. If patients achieved SVR, their MELD scores were adjusted based on the reported data (Supplementary Figure S1); otherwise, their MELD scores continued to follow the natural course of the disease until they received a transplant. To determine the clinical course of patients, we used a previously published study based on UNOS data to estimate weekly increase or decrease in MELD score, i.e., the natural course of the disease (14, 15). We also estimated mortality on the waiting list based on the MELD score from the same data source (Supplementary Table S1).

Three months after the liver transplant, patients received treatment if they were still viremic. If patients cleared HCV RNA, they moved to the SVR state; otherwise, they progressed to F0–F2 state (Figure 1). Patients’ graft could fail; in that case they would go back to the waiting list and would be eligible for re-transplantation.

Liver transplant

We used a published study to estimate weekly probability of receiving an LT based on a patient’s current MELD score (16) (Supplementary Table S2). For patients who were treated for HCV on the waiting list, we accounted for reduction in the probability of getting a LT since they will no longer be eligible to receive HCV-positive liver. Specifically, we narrowed the donor pool by 8% and adjusted the probability of getting an LT accordingly (17). Patients who needed retransplantation went back to the LT waiting list. Because we did not know their MELD score at that time, we assigned the average probability of liver transplant and liver-related mortality to these patients, which were estimated from UNOS data. Specifically, the weekly probability of death and receiving an LT in patients who had graft failure were estimated as 0.020 and 0.0308, respectively (Supplementary Table S3).

Costs

Patients in both strategies incurred costs that included the cost on the waiting list, one-time cost of the transplantation, and the annual cost of post-LT patient management. We used previously published studies to determine the health-state costs in our model (Supplementary Table S3) (18, 19). Treatment costs included the wholesale acquisition costs of sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and ribavirin (20). All costs were converted to 2016 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index. We conducted sensitivity analysis on a wide range of costs.

Health-related quality of life

We assigned health-related quality-of-life (QoL) utilities for each health state in our model, with 0 denoting death and 1 denoting perfect health, and adjusted them for age and sex. We derived EuroQol-5D instrument values from published studies and adjusted them to the US population norm (Supplementary Tables S3–S4) (21–23).

Model Outcomes

For each MELD score, we estimated total costs, life years, QALYs and the ICER for pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment. We also projected these outcomes for each of the 11 UNOS regions. Specifically, we adjusted the probability of undergoing LT and mortality on the waiting list for each region using region-specific transplantation and death rates (Supplementary Table S5). We also compared regions according to the incremental net monetary benefit of treating patients before LT in that region. All future costs and QALYs were discounted at 3% per year.

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed one-way sensitivity analysis on the selected MELD scores where the cost-effectiveness results changed and estimated the impact of model parameters on the ICER. We further conducted probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) by simultaneously changing all model parameters for 50,000 first-order and 1,000 second-order samples using the recommended statistical distributions to define uncertainty around each model parameter (Supplementary Table S3). We then calculated the probability of cost-effectiveness of pre-LT HCV treatment for each MELD score at the commonly accepted willingness to pay (WTP) threshold, i.e. $100,000.

RESULTS

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

QALYs of pre-LT and post-LT treatment varied by patients’ MELD scores. For lower MELD scores, QALYs were higher with pre-LT HCV treatment compared to post-LT treatment, implying that pre-LT HCV treatment was more effective. However, for higher MELD scores, the trend was reversed (Table 1). Patients with MELD score ≤ 27 could benefit from HCV treatment before LT, and those above the threshold would benefit from waiting until after LT for treatment.

Table 1.

Cost-effectiveness of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment by MELD score

| MELD Score | QALYs | Difference in QALYs (95% CI) | Cost | ICER* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-LT | Post-LT | Pre-LT | Post-LT | |||

| 10–11 | 9.27 | 7.42 | 1.85 (0.31–3.13) | $ 411,458 | $ 534,466 | Pre-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 12–13 | 9.49 | 7.36 | 2.13 (0.51–3.45) | $ 439,847 | $ 554,485 | Pre-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 14–15 | 9.12 | 7.21 | 1.91 (0.56–3.03) | $ 493,009 | $ 568,479 | Pre-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 16–17 | 8.68 | 7.05 | 1.63 (0.78–2.31) | $ 582,284 | $ 577,394 | $3,006 (pre-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 18–19 | 7.84 | 6.79 | 1.05 (0.65–1.46) | $ 615,175 | $ 570,057 | $42,630 (pre-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 20–21 | 7.26 | 6.53 | 0.73 (0.49–0.95) | $ 625,528 | $ 557,484 | $92,764 (pre-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 22–23 | 6.66 | 6.18 | 0.48 (0.30–0.65) | $ 598,155 | $ 535,725 | $128,322 (post-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 24–25 | 6.05 | 5.74 | 0.31 (0.17–0.42) | $ 561,653 | $ 502,224 | $195,228 (post-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 26–27 | 4.94 | 4.80 | 0.14 (0.04–0.24) | $ 467,435 | $ 422,828 | $336,557 (post-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 28–29 | 3.96 | 3.93 | 0.03 (−0.04–0.12) | $ 379,605 | $ 347,232 | $991,565 (post-LT Tx is cost-effective) |

| 30–31 | 2.98 | 3.03 | −0.05 (−0.12–0.03) | $ 289,873 | $ 268,505 | Post-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 32–33 | 2.36 | 2.42 | −0.06 (−0.12–0.01) | $ 232,408 | $ 215,166 | Post-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 34–35 | 1.92 | 1.97 | −0.05 (−0.10–0.01) | $ 191,277 | $ 175,296 | Post-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 36–37 | 1.38 | 1.41 | −0.03 (−0.08–0.02) | $ 139,192 | $ 125,081 | Post-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 38–39 | 1.05 | 1.09 | −0.04 (−0.06–0.02) | $ 107,594 | $ 96,490 | Post-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

| 40 | 0.65 | 0.66 | −0.01 (−0.05–0.02) | $ 67,896 | $ 58,624 | Post-LT Tx is cost saving (ICER < $0) |

ICER of pre-LT HCV treatment with DAAs compared with post-LT HCV treatment using the price of DAAs equal to $95,523 for 12 weeks

Shaded rows show MELD scores below which pre-LT HCV treatment is clinically more effective because difference in QALYs was statistically positive (i.e. 95% CI was above 0).

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; Tx, Treatment; QALY, Quality-adjusted life years; CI, Confidence interval, ICER, Incremental cost effectiveness ratio.

When we accounted for costs, we found that pre-LT HCV treatment was cost-saving (i.e., increase QALYs and decrease costs) in patients with MELD score ≤15, and cost-effective (i.e. increase QALYs and costs but one is willing to pay for higher costs) in patients with MELD scores 16–21 at the commonly accepted WTP threshold of $100,000-per-QALY (Table 1).

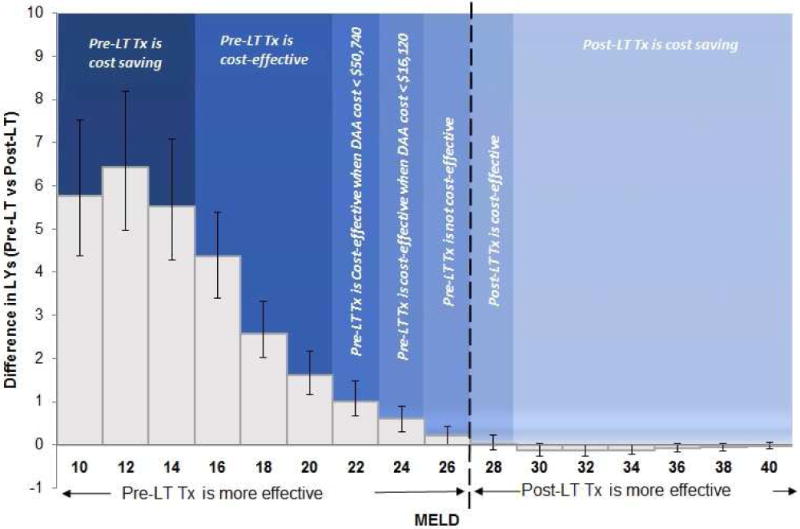

However, in patients with MELD scores 22–27, even though pre-LT HCV treatment resulted in higher QALYs, treatment was not cost-effective (ICER > $100,000/QALY). If the price of DAAs decreased below $51,000 (i.e., $4,250/week) and $16,000 (i.e., $1,333/week), pre-LT treatment became cost-effective in patients with MELD 22–23 and MELD 24–25, respectively. However, for MELD 26–27 no price reduction could make pre-LT treatment cost-effective (Figure 2). For patients with MELD score ≥ 27, post-LT HCV treatment was more effective as well as cost-effective. Furthermore, in patients with MELD score ≥ 30, post-LT HCV treatment resulted in cost-savings.

Figure 2. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment with DAAs before versus after the liver transplant.

The dotted line shows the clinical threshold below which pre-LT treatment is more effective than post-LT treatment. Different shaded regions represent the cost-effectiveness of the timing of HCV treatment.

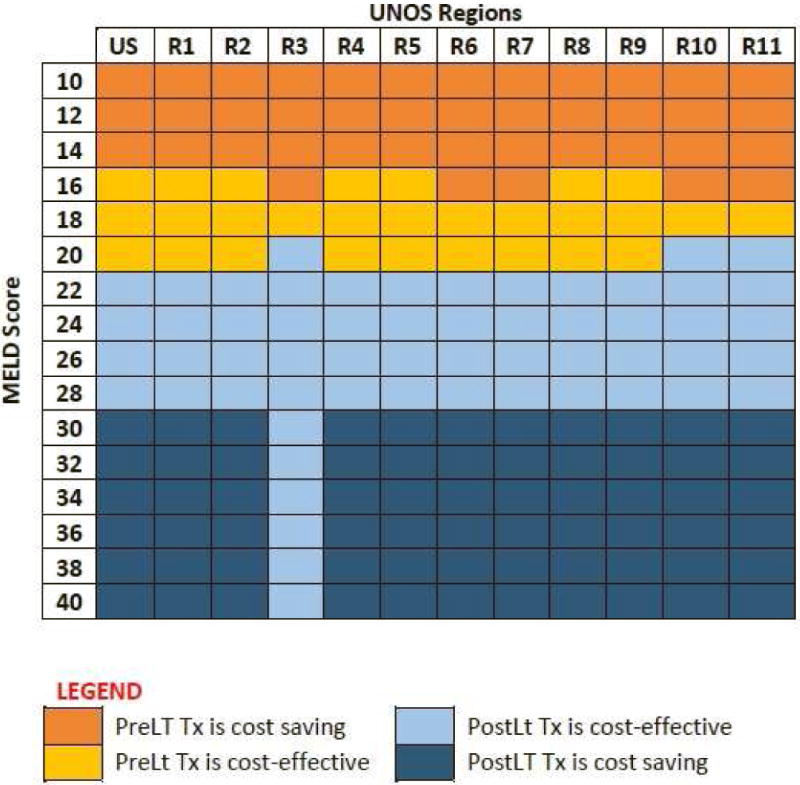

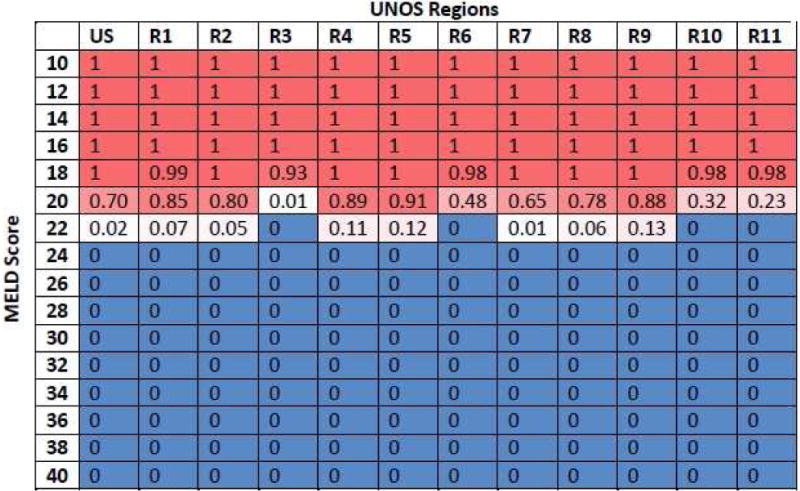

Cost-Effectiveness by UNOS Regions

We also analyzed the results for each UNOS region to account for differences in waiting time for LT. For Region 3, Region 10 and Region 11, which had relatively shorter waiting times for LT, pre-LT treatment was cost-effective/saving in patients with MELD ≤ 19 (rather than 21). For the other regions, cost-effectiveness results remained the same as the national results (Figure 3). The price threshold for DAAs below which pre-LT HCV treatment remained cost-effective varied between $8,600–$74,000, depending on the MELD score and UNOS region (Supplementary Figure S2–S12). The incremental net monetary benefit or pre-LT treatment was lower for regions having shorter time on the waiting list (Supplementary Figure S13).

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness of pre- versus post-LT HCV treatment by MELD score and UNOS regions.

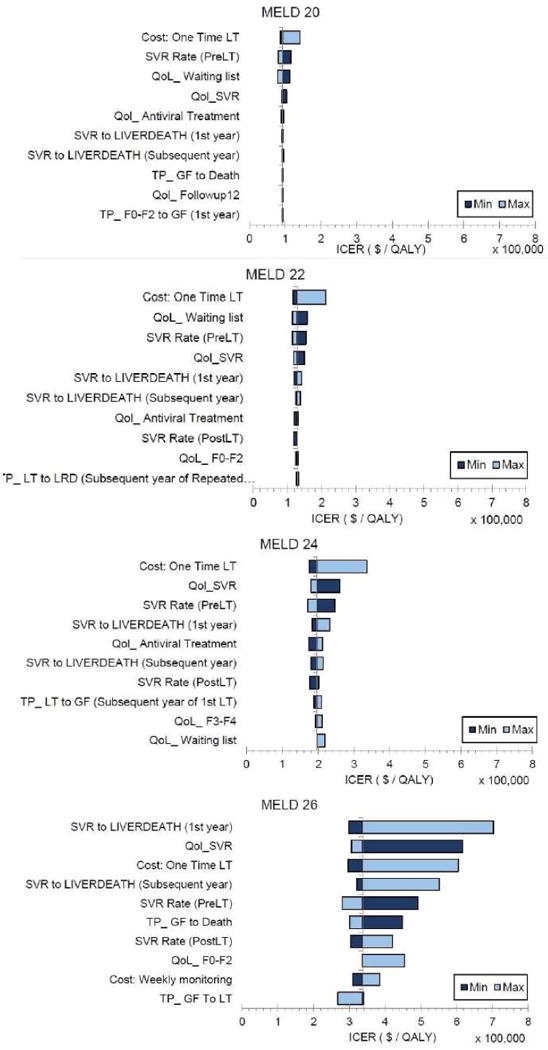

Sensitivity Analysis

Because the cost-effectiveness decisions changed at MELD scores 20, 22, 24, and 26, we conducted one-way sensitivity analysis on these MELD scores to estimate the impact of model parameters on the ICER. The 10 most sensitive model parameters for each MELD score are shown by tornado diagrams (Figure 4). For MELD scores 22, 24 and 26, none of the parameters changed the cost effectiveness of pre-LT HCV treatment. For MELD 20, the model was sensitive to the cost of the liver transplant, SVR rate for pre-LT HCV treatment and QoL of patients on the waiting list and those who had SVR.

Figure 4.

Tornado Diagrams Showing 10 Most Sensitive Model Parameters for MELD 20, 22, 24 and 26.

The probabilistic sensitivity analysis at the national level found that pre-LT HCV treatment was cost-effective with a high probability (0.7–1.0) in patients having MELD scores ≤ 21, and vice versa (Figure 5). Some variation was observed in the results of UNOS regions 3, 6, 10, 11 in patients having MELD scores 20–21, where the probability of cost-effectiveness of pre-LT HCV treatment was below 0.5.

Figure 5.

Probability of cost-effectiveness of pre-LT treatment at the willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000-per-QALY

DISCUSSION

Oral DAAs offer new hope for improving long-term outcomes in HCV-infected patients with decompensated cirrhosis. However, the decision to treat HCV—pre-LT versus post-LT, needs to balance the benefits and potential harms of HCV treatment in patients on the LT waiting list. In addition, such trade-offs need to factor-in the cost-effectiveness and value of pre-LT versus post-LT HCV treatment. In this study, we simulated a virtual clinical trial to evaluate such trade-offs and found that pre-LT HCV treatment was cost-effective/saving in patients with MELD scores ≤ 21. Waiting to treat until after LT was the most cost-effective/saving strategy in patients with higher MELD score. These results may guide clinicians and payers about the optimal timing of HCV treatment in decompensated cirrhotic patients who are liver transplant candidates.

Prior studies have provided conflicting evidence about the cost-effectiveness of timing of HCV treatment (7–9). Our study supports the results by Njei et al. (9), that found that pre-LT HCV treatment is cost-effective in patients with lower MELD scores (MELD ≤ 25) and post-LT treatment is cost-effective in patients with higher MELD scores. In contrast, Ahmed et al. (7) and Tapper et al. (8) concluded that pre-LT HCV treatment was always cost-effective in patients on the waiting list. We believe the reason for these conflicting findings is that these studies aggregated all patients with MELD scores ≥15 into one category and thus failed to identify a threshold above which post-LT HCV treatment could be cost-effective. In fact, a previous study showed that pre-LT HCV treatment in patients having MELD>27 could harm them by delaying their LT (10). Our study, because it considered MELD as a continuum, provides more granular results by MELD scores and thus aids patient-level decision making. Furthermore, we also analyzed results for each UNOS region, which had not been previously performed.

Our study has numerous strengths. First, we conducted a comprehensive analysis to determine the optimal time for HCV treatment in terms of cost-effectiveness. We used a validated mathematical model that simulated a virtual trial comparing the long-term clinical and cost outcomes in decompensated cirrhotic patients (10). Second, our study analyzed cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment timing by each MELD score between 10 and 40. Third, we accounted for lower transplant rates if HCV patients were treated on the waiting list; therefore, these patients would not be eligible for HCV-infected donor organs. Fourth, although we used sofosbuvir-based therapy, our analysis is not limited to any particular regimen and applies to other DAAs that are currently used or will be approved in the near future. Finally, our study incorporated the differences between regions in terms of transplant rates and provided cost-effectiveness of pre-LT HCV treatment by each UNOS region.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, our analysis did not include cirrhotic patients with HCC who receive disease exception points. Second, we did not explicitly model Child Turcotte-Pugh class in our analysis and this should be considered in future studies as more data become available. Third, we assumed that patients could receive post-LT HCV treatment only once; however re-treatments with oral DAAs may be offered to LT patients in the future. Fourth, we did not model patient dropout from the waiting list resulting from MELD improvement. Although we did not consider patient delisting, recent clinical data shows that only 20% patients and those having MELD≤20 were delisted because of treatment with DAAs (24). Because our model recommended that patients with MELD≤23 receive pre-LT HCV treatment, consideration of “delisting” would not have changed our conclusions. However long-term data are necessary to determine the true benefit of DAAs and their impact of delisting. Fifth, our model did not adjust for survival based on MELD score at transplant; adjusting for survival could have resulted in a higher MELD threshold to provide post-LT HCV treatment. Sixth, our model did not incorporate MELD-Na, which is not expected to impact our results because changes in MELD-Na after SVR would be anticipated to follow the same trend as that observed with MELD. Seventh, we did not consider the fact that some patients will not tolerate ribavirin and thus would need 24 weeks of SOF/LDV. Finally, our model did not account for potential reduction in the LT waiting list size because of delisting of HCV patients after successful antiviral therapy and decreasing need for LT in HCV patients because of the availability of DAAs.

Sensitivity analysis suggested that our model’s results remained robust with an exception in patients having MELD score of 20. The most sensitive parameter at that MELD score was the cost of liver transplant—lower cost of LT could make pre-LT HCV treatment more cost-effective. In addition, the MELD threshold below which pre-LT treatment would be cost-effective/saving increased from 21 to 25 as the price of DAAs reduced from $95,500 to $16,100. We also accounted for uncertainty in model parameters by conducting probabilistic sensitivity analysis and presented the probability of cost-effectiveness of pre-LT treatment. We found that our results and conclusions remain robust when simultaneously accounting for uncertainty in model parameters. We also observed small differences in the cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment timing by UNOS regions. Because liver transplant rates vary across regions, patient-level decisions for cost-effectiveness of pre- versus post-LT treatment should be dependent on UNOS region.

We do not recommend that clinicians or payers should make decision about the timing of HCV treatment guided exclusively by cost-effectiveness analysis. Instead, we propose a comprehensive approach to the decision that includes patients’ perspective, clinical effectiveness, budget constraints, and medical urgency not captured by MELD score. For example, some patients could benefit from pre-LT HCV treatment (i.e., long-term survival will be higher) compared with waiting until after the LT, even if pre-LT HCV treatment is not cost-effective. In such cases, lower prices of DAAs could make pre-LT treatment cost-effective.

In conclusion, our study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of providing HCV treatment before and after LT in decompensated cirrhotic patients. Pre-LT HCV treatment was cost-effective/saving in patients with MELD ≤ 21, and could be cost-effective in patients with MELD scores between 22 and 25 at lower DAA prices. Post-LT treatment was the most cost-effective/saving strategy in patients with higher MELD score. These data should be useful in informing decision making for patients with HCV infection who are awaiting LT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Chung has received research grants from Gilead, Abbvie, Merck, BMS; Chhatwal has received research grant from Gilead and consulting fee from Merck and Gilead.

Abbreviations

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- DAAs

Oral direct-acting antivirals

- LT

Liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End-stage Liver Disease

- SIM-LT

simulation of liver transplant candidates

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- QALY

Quality-adjusted life year

- ICER

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- SVR

Sustained virologic response

- QoL

Quality-of-life

- PSA

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

- WTP

Willingness to pay

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Author contributions:

Study concept and design: SS, BK, TA, JC, RC

Acquisition of data: SS, BK, JC, DMD

Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors

Drafting of the manuscript: SS, JC

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors

Statistical analysis: SS, DMD

Study supervision: JC

References

- 1.Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:2429–2438. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Management of Hepatitis C Before and After Liver Transplantation in the Era of Rapidly Evolving Therapeutic Advances. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology. 2014;2:124–133. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roche B, Samuel D. Hepatitis C virus treatment pre- and post-liver transplantation. Liver International. 2012;32:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curry MP, Forns X, Chung RT, Terrault NA, Brown R, Jr, Fenkel JM, Gordon F, et al. Sofosbuvir and Ribavirin Prevent Recurrence of HCV Infection After Liver Transplantation: An Open-Label Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:100–107 e101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrion AF, Khaderi SA, Sussman NL. Model for end-stage liver disease limbo, model for end-stage liver disease purgatory, and the dilemma of treating hepatitis C in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. 2016;22:279–280. doi: 10.1002/lt.24383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canary LA, Klevens R, Holmberg SD. LImited access to new hepatitis c virus treatment under state medicaid programs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163:226–228. doi: 10.7326/M15-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed A, Gonzalez SA, Cholankeril G, Perumpail RB, McGinnis J, Saab S, Beckerman R, et al. Treatment of Patients Waitlisted for Liver Transplant with an All‐Oral DAAs is a Cost‐ Effective Treatment Strategy in the United States. Hepatology. 2017 Mar 3; doi: 10.1002/hep.29137. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tapper EB, Hughes MS, Buti M, Dufour J-F, Flamm S, Firdoos S, Curry MP, et al. The optimal timing of hepatitis C therapy in transplant eligible patients with Child B and C Cirrhosis: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Transplantation. 2016 Aug 4; doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001400. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Njei B, McCarty TR, Fortune BE, Lim JK. Optimal timing for hepatitis C therapy in US patients eligible for liver transplantation: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1090–1101. doi: 10.1111/apt.13798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chhatwal J, Samur S, Kues B, Ayer T, Roberts MS, Kanwal F, Hur C, et al. Optimal timing of hepatitis C treatment for patients on the liver transplant waiting list. Hepatology. 2017;65:777–788. doi: 10.1002/hep.28926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL, Kumar P, Landis C, Brown RS, Jr, Fried MW, et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir Plus Ribavirin for Treatment of HCV Infection in Patients With Advanced Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:649–659. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manns M, Samuel D, Gane EJ, Mutimer D, McCaughan G, Buti M, Prieto M, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus infection and advanced liver disease: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16:685–697. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gane E, Manns M, McCaughan G, Curry MP, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Vlierberghe HV, Arterburn S, et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with ribavirin in patients with decompensated cirrhosis or liver transplantation and HCV infection: SOLAR-1 and -2 trials. AASLD Abstract. 2015;1049:2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shechter SM, Bryce CL, Alagoz O, Kreke JE, Stahl JE, Schaefer AJ, Angus DC, et al. A clinically based discrete-event simulation of end-stage liver disease and the organ allocation process. Medical Decision Making. 2005;25:199–209. doi: 10.1177/0272989X04268956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alagoz O, Maillart LM, Schaefer AJ, Roberts MS. The optimal timing of living-donor liver transplantation. Management Science. 2004;50:1420–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massie AB, Caffo B, Gentry SE, Hall EC, Axelrod DA, Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, et al. MELD Exceptions and Rates of Waiting List Outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2362–2371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai JC, O’Leary JG, Trotter JF, Verna EC, Brown RS, Jr, Stravitz RT, Duman JD, et al. Risk of advanced fibrosis with grafts from hepatitis C antibody-positive donors: a multicenter cohort study. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:532–538. doi: 10.1002/lt.23396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saab S, Hunt DR, Stone MA, McClune A, Tong MJ. Timing of hepatitis C antiviral therapy in patients with advanced liver disease: a decision analysis model. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:748–759. doi: 10.1002/lt.22072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAdam-Marx C, McGarry LJ, Hane CA, Biskupiak J, Deniz B, Brixner DI. All-cause and incremental per patient per year cost associated with chronic hepatitis C virus and associated liver complications in the United States: a managed care perspective. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17:531–546. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.7.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RedBook Online. 2014 Available from: http://www.redbook.com/redbook/online/. Accessed November 10, 2015.

- 21.Chhatwal J, Kanwal F, Roberts MS, Dunn MA. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis C virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:397–406. doi: 10.7326/M14-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson Coon J, Rogers G, Hewson P, Wright D, Anderson R, Jackson S, Ryder S, et al. Surveillance of cirrhosis for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-utility analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1166–1175. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong CAKY, Gulamhussein A, Heathcote EJ, Lilly L, Sherman M, Naglie G, Krahn M. Health-state utilities and quality of life in hepatitis C patients. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98:630–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belli LS, Berenguer M, Cortesi PA, Strazzabosco M, Rockenschaub SR, Martini S, Morelli C, et al. Delisting of liver transplant candidates with chronic hepatitis C after viral eradication: A European study. J Hepatol. 2016;65:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.