Abstract

Changes in dietary patterns may partly explain the epidemic of asthma in industrialized countries. The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between dietary patterns and lung function and asthma exacerbations in Puerto Rican children. This is a case–control study of 678 Puerto Rican children (ages 6–14 years) in San Juan (Puerto Rico). All participants completed a respiratory health questionnaire and a 75-item food frequency questionnaire. Food items were aggregated into 7 groups: fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, dairy, fats, and sweets. Logistic regression was used to evaluate consumption frequency of each group and asthma. Based on the results, a dietary score was created [range from −2 (unhealthy diet: high consumption of dairy and sweets, low consumption of vegetables and grains) to 2 (healthy diet: high consumption of vegetables and grains and low consumption of dairy and sweet)]. Multivariable linear or logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between dietary score and lung function or asthma exacerbations. After adjustment for covariates, a healthier diet (each 1-point increment in dietary score) was associated with significantly higher %predicted forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and %predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) in control subjects. Dietary pattern alone was not associated with asthma exacerbations, but children with an unhealthy diet and vitamin D insufficiency (plasma 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL) had higher odds of ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation [odds ratio (OR) = 3.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.5–7.5] or ≥1 hospitalization due to asthma (OR = 3.9, 95% CI = 1.6–9.8, OR = 3.4, 95% CI = 1.5–7.5) than children who ate a healthy diet and were vitamin D sufficient. A healthy diet, with frequent consumption of vegetables and grains and low consumption of dairy products and sweets, was associated with higher lung function (as measured by FEV1 and FVC). Vitamin D insufficiency, together with an unhealthy diet, may have detrimental effects on asthma exacerbations in children.

Keywords: : diet, asthma, lung function, asthma exacerbation, children

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common respiratory diseases among children worldwide.1 Whereas the prevalence of asthma in industrialized countries has reached a relative plateau (after a sharp rise from the 1960s to the 1990s), such prevalence has continued to increase in low and middle income countries.2 Changes in dietary patterns or nutrient intake could partly explain this “asthma epidemic” over the past few decades.3

Recent studies of the diet–disease link have shifted their focus from single nutrients to dietary patterns. An unbalanced diet, such as that having excessive intake of calories and saturated fat but deficient intake of micronutrients or vitamins from fruits and vegetables, can modulate allergic airway inflammation by affecting both innate and adaptive immune responses.4 A “Mediterranean diet” (characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, and olive oil, but low intake of refined grains and saturated fats) may protect against the development of asthma or asthma symptoms during childhood.5,6 In contrast, a “Western” diet (low in fruits and vegetables, but high in refined grains and saturated fats) could increase the risk of asthma in children.7 Frequent consumption of sugar-added drinks8 or total excess free fructose9 has also been associated with childhood asthma.

In the United States, Puerto Rican children share a disproportionate burden of asthma.10,11 Unhealthy dietary habits have been reported among Puerto Rican adolescents, including low intake of fruits or vegetables but high consumption of sweetened drinks.12 We previously reported that frequent consumption of vegetables or grains was associated with lower odds of asthma, whereas frequent consumption of dairy products or sweets was associated with higher odds of asthma in Puerto Rican children, and that such findings may be partly explained by dietary effects on interleukin (IL)-17F-dependent pathways.13 Thus, we hypothesized that such dietary patterns may affect lung function and asthma attacks among these children. We examined whether dietary patterns are associated with lung function and asthma exacerbations in Puerto Rican children. Because vitamin D insufficiency (a plasma 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL) has been linked to asthma exacerbations in Puerto Rican children, the second aim is to assess potential synergistic effects of an unhealthy diet and vitamin D insufficiency on asthma exacerbations in the study participants.14

Materials and Methods

Study population

Subject recruitment and study procedures have been previously described in detail.15,16 In brief, study participants were recruited from randomly selected households in the metropolitan area of San Juan (Puerto Rico) from March 2009 through June 2010. Households were selected by a multistage probability sampling design. Primary sampling units were randomly selected neighborhood clusters based on the 2000 U.S. census, and secondary units were randomly selected households within each primary sampling unit. A household was eligible if at least 1 resident was a child 6–14 years old. Of the 7,073 selected households, 6,401 (∼91%) were contacted. Of these 6,401 households, 1,111 had at least 1 child aged 6–14 years who met other inclusion criteria (4 Puerto Rican grandparents and residence in the same household for at least 1 year). Of these 1,111 households, 438 (39.4%) had at least 1 eligible child with asthma (a case, defined as parental report of having physician-diagnosed asthma and at least 1 episode of wheeze in the previous year). From these 438 households, 1 child with asthma was selected (at random if there was more than 1 eligible child). Similarly, only 1 child without asthma (a control, defined as parental report of having neither physician-diagnosed asthma nor wheeze in the previous year) was randomly selected from the remaining 673 households. To reach a target sample of ∼700 children, the study attempted to enroll a random sample (n = 783) of these 1,111 children. Parents of 105 of these 783 households refused to participate or could not be reached. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or area of residence between eligible children who did [n = 678 (86.6%)] and did not [n = 105 (13.4%)] participate.

Written parental consent and assent were obtained for participating children. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Puerto Rico (San Juan, Puerto Rico) Brigham, and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA), and the University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA).

Study procedures

One of the child's caretakers (usually the mother) completed a questionnaire slightly modified from that used in the Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Asthma,17 containing questions about demographics, the child's general and respiratory health, family history of asthma, breastfeeding, second-hand tobacco smoke, and outdoor physical activity. Height and weight were measured to the nearest centimeter and kilogram, respectively. Dietary data were collected using a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) adapted from that developed and validated to measure intake of 75 food items in a Hispanic population (Costa Ricans).18

Spirometry was conducted with an EasyOne spirometer (NDD Medical Technologies, Andover, MA), following American Thoracic Society recommendations for children.19 The best forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were selected for data analysis. Serum levels of total immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgEs specific to common allergens [dust mite (Der p 1), cockroach (Bla g 2), cat dander (Fel d 1), dog dander (Can f 1), and mouse urinary protein (Mus m 1)] were determined using the UniCAP 100 system (Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI). For data analysis, total serum IgE was converted to a log10 scale; for each allergen, an IgE ≥0.35 IU/mL was considered positive. Vitamin D (25(OH)D) was measured using the Waters high-performance liquid chromatography system with tandem mass spectrophotometry (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). Plasma IL-17F was measured using the Bio-Plex Pro Human TH17 cytokine panel on the BioPlex HTF system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA), as previously described13; levels are presented as pg/mL. Undetectable IL-17F levels were assigned a constant (half the lowest limit of detection), and IL-17F levels were then log-transformed for data analysis.

Dietary score

The dietary score was defined by frequency of food group consumption, as previously described.13 Based on a food guidance system developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion,20 each of the 75 FFQ items was assigned to 1 of 6 food groups: fruits, vegetables, grains, proteins, dairy, and fats. A seventh group (sweets, soda, and snacks) was added for completeness. Multivariate logistic regression was then used to analyze quartiles of food group consumption and asthma, and a dietary score was created including food groups that were significantly associated with increased (vegetables and grains, healthy food groups) or decreased (dairy and sweets, unhealthy food groups) odds of asthma. Because fruits, proteins, and fats were not associated with asthma, these 3 groups were not considered in the dietary score.13 Study participants were assigned a score of +1 for high consumption of healthy food groups or −1 for consumption of unhealthy food groups. Thus, the dietary score ranges from −2 (most “unhealthy diet”) to +2 (most “healthy diet”).

Statistical analysis

Our outcomes of interest were lung function measures (FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC) and asthma exacerbation outcomes ≥1 severe exacerbation [defined as a visit to the ED/urgent care or a hospitalization for asthma, requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids (oral, intramuscular, or intravenous) for at least 3 days] and ≥1 hospitalization for asthma in the previous year. Secondary outcomes included total IgE, atopy (≥1 positive allergen-specific IgE), and IL-17F level. FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC z-scores and percentage (%) predicted FEV1 and FVC were calculated using Global Lung Initiative equations that account for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and height.21 The %predicted values of lung function were used as the primary outcomes and z-scores were used in a confirmatory analysis.

Data analysis was first conducted in all subjects, and then separately in cases and control subjects. Bivariate analyses were performed using 2-sample t-tests (for pairs of binary and continuous variables) or χ2 tests (for categorical variables). Linear or logistic regression was used for the multivariable analysis of dietary score or dietary pattern and the outcomes of interest. Covariates included in the regression models were age, sex, annual household income (<$15,000 or ≥$15,000, the median annual household income in Puerto Rico in 2008–2009), health insurance (private or employer-based versus others), parental history of asthma, early life (in utero or before 2 years of age) exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS), body mass index (BMI) z-score, outdoor physical activity (moderate to intense versus none to minimal), breastfeeding (never, ≤6 months, or >6 months), and (for the analysis in all subjects) case–control status.

Because we previously showed that vitamin D insufficiency (defined as a serum 25(OH)D level <30 ng/mL) is associated with severe asthma exacerbations in Puerto Rican children,14 we tested for an interaction between dietary score (dichotomized—for ease of exposition) as healthy (a dietary score ≥1) or unhealthy (a dietary score ≤0) and vitamin D insufficiency on severe asthma exacerbations. Given a significant interaction, we next conducted an analysis of the binary dietary score (as mentioned) and asthma exacerbations, stratified by vitamin D insufficiency. Since we previously reported that vitamin D insufficiency has a stronger effect on disease exacerbations in children with nonatopic asthma than in those with atopic asthma,14 we repeated this stratified analysis separately in children with asthma and ≥1 positive IgE to allergens (atopic asthma) and in those with asthma but no positive IgE to any allergen (nonatopic asthma)

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of participating children. Compared with children without asthma (n = 327), those with asthma (n = 351) were slightly younger, more likely to be male and atopic, and to have a parental history of asthma, early life exposure to SHS, lower dietary score and lung function measures (FEV1 and FEV1/FVC), and higher levels of total IgE and IL-17F. Most asthmatic children (96%) had mild to moderate airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC >60%, data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Covariate | Control (n = 327) | Case (n = 351) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 10.5 (2.7) | 10.0 (2.6)* |

| Sex (male) | 159 (48.6) | 201 (57.3)* |

| BMI, z-score | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.2) |

| Annual household income <$15,000 | 196 (62.8) | 225 (65.4) |

| No private or employer-based health insurance | 205 (62.7) | 239 (68.1) |

| Breastfed | ||

| Never | 142 (44.4) | 159 (45.6) |

| ≤6 months | 152 (47.5) | 144 (41.3) |

| >6 months | 26 (8.1) | 46 (13.2) |

| Parental asthma | 103 (31.7) | 232 (66.3)* |

| Early life exposure to SHS | 131 (41.9) | 174 (51.6)* |

| Outdoor activitya | 240 (73.4) | 268 (76.4) |

| Vitamin D insufficiency (25[OH]D <30 ng/mL) | 136 (46.4) | 135 (43.4) |

| Dietary score | 0.9 (1.0)* | 0.6 (1.0)* |

| Atopy (≥1 positive allergen-specific IgE) | 143 (49.8) | 210 (68.9)* |

| Total IgE (IU/mL) | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.9)* |

| Interleukin-17Fb | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.0)* |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1 (L) | ||

| %Predicted | 97.8 (15.0) | 92.9 (15.3)** |

| z-Score | −0.17 (1.25) | −0.58 (1.25)** |

| Prebronchodilator FVC (L) | ||

| %Predicted | 104.8 (18.0) | 102.1 (15.8) |

| z-Score | 0.40 (1.56) | 0.17 (1.38) |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1/FVC | ||

| Ratio (%) | 83.5 (9.0) | 80.9 (9.0)** |

| z-Score | −0.82 (1.27) | −1.19 (1.16)** |

| At least 1 severe asthma exacerbation in the prior year | 96 (27.4) | |

| At least 1 hospitalization for asthma in the prior year | 75 (21.4) | |

Data are presented as number (percentage) for binary variables or mean (SD) for continuous variables. Percentages were calculated for children with complete data.

At least a moderate amount of outdoor activity including playing, practicing sports, and walking.

Data were log10 transformed.

P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 for the comparison between control and case groups (conducted using 2-sample t-tests or χ2 tests, as appropriate).

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity; SD, standard deviation; SHS, second-hand smoke.

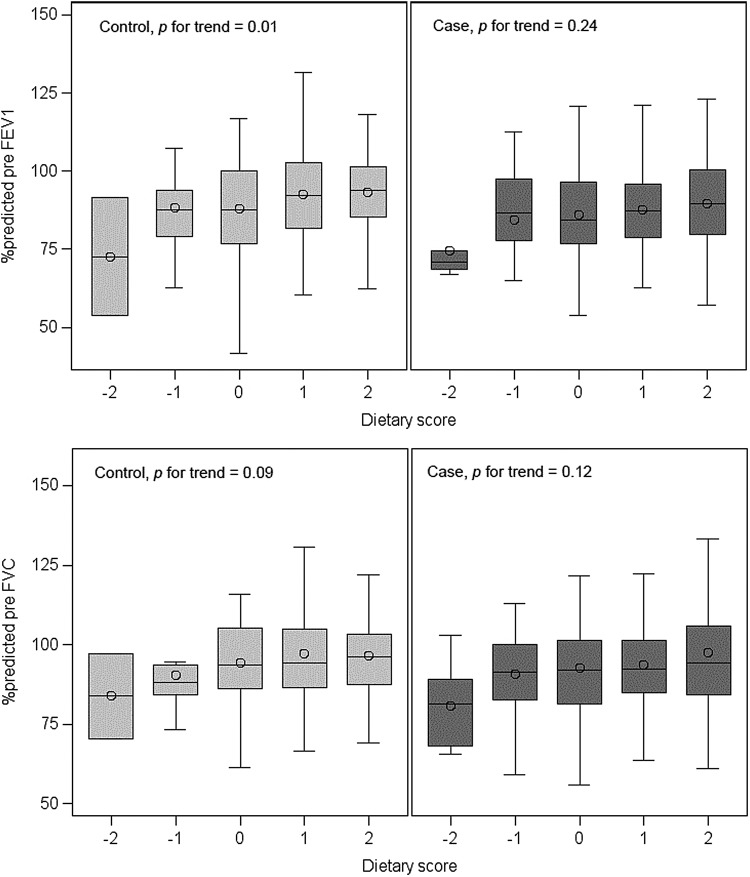

The bivariate analysis of dietary score and %predicted FEV1 and FVC, conducted separately in cases and in control subjects, is illustrated in Figure 1. Dietary score was positively associated with FEV1 (P for trend = 0.01) and FVC (P for trend = 0.09) in control subjects, but not in cases. After adjustment for relevant covariates, dietary score was significantly associated with higher FEV1 [β per each 1-point increment in dietary score = 2.79%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.83–4.76], higher FVC (β per each 1-point increment in dietary score = 2.43%, 95% CI 0.32–4.54), and lower IL-17F levels (β per each 1-point increment in dietary score = −0.26, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.13) in control subjects, but not in cases (Table 2). Similar results were obtained when lung function measures were analyzed as z-scores. Dietary score was not significantly associated with FEV1/FVC, total IgE, or ≥1 positive allergen-specific IgE in cases or control subjects.

FIG. 1.

Lung function and dietary score by case–control status. Dietary score ranges from −2 (most “unhealthy diet”) to +2 (most “healthy diet”). Study participants were assigned a score of +1 for high consumption of healthy food groups or −1 for consumption of unhealthy food groups.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Dietary Score and Lung Function and Other Outcomes

| Dietary scorea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | All subjects | Controls only | Cases only |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1 | |||

| %Predicted | 1.82 (0.50 to 3.14)** | 2.79 (0.83 to 4.76)** | 0.88 (−0.91 to 2.67) |

| z-Score | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.26)** | 0.23 (0.07 to 0.40)** | 0.07 (−0.08 to 0.22) |

| Prebronchodilator FVC | |||

| %Predicted | 1.85 (0.47 to 3.22)** | 2.43 (0.32 to 4.54)* | 1.27 (−0.54 to 3.08) |

| z-Score | 0.16 (0.04 to 0.28)** | 0.22 (0.03 to 0.40)* | 0.11 (−0.05 to 0.27) |

| Prebronchodilator FEV1/FVC | |||

| Ratio (%)b | 0.26 (−0.52 to 1.04) | 0.54 (−0.60 to 1.68) | 0.09 (−1.01 to 1.19) |

| z-Score | 0.03 (−0.08 to 0.13) | 0.07 (−0.08 to 0.25) | −0.03 (−0.17 to 0.12) |

| Interleukin-17Fb | −0.15 (−0.24 to −0.06)** | −0.26 (−0.39 to −0.13)** | −0.05 (−0.18 to 0.07) |

| Total IgEb | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.07) | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.12) | −0.01 (−0.09 to 0.08) |

| ≥1 positive allergen-specific IgEb | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) | 0.03 (−0.04 to 0.09) | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.10) |

Data are presented as β (95% confidence interval).

All models were adjusted for annual household income, parental history of asthma, BMI z-score, breastfeeding, outdoor physical activity, early life exposure to SHS, and case–control status (for all subjects).

Dietary score ranges from −2 for the most “unhealthy diet” to 2 for the most “healthy diet.”

In addition adjusting for age and sex.

P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

IgE, immunoglobulin E.

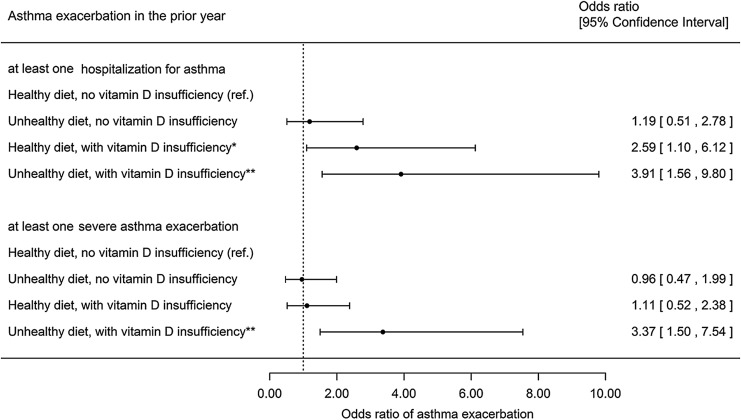

Dietary pattern alone was not significantly associated with asthma exacerbations (eg, OR 1.55, 95% CI 0.92–2.63 for ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation). Next, we tested whether vitamin D insufficiency modifies the estimated effect of diet on asthma exacerbation outcomes. Since we found a significant interaction between vitamin D insufficiency and dietary score (P = 0.04, data not shown) in a multivariable model, we repeated the analysis after stratification by vitamin D insufficiency (Fig. 2). In this analysis, children with an unhealthy diet and vitamin D insufficiency had significantly higher odds of ≥1 hospitalization for asthma (OR 3.91, 95% CI 1.56–9.80) or ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation (OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.50–7.54) in the previous year than those who ate a healthy diet and had sufficient vitamin D levels. Similar results were obtained when the analysis was additionally adjusted for season of collection of the blood sample for vitamin D measurement.

FIG. 2.

Multivariate analysis of asthma exacerbation by dietary pattern and vitamin D status. All models were compared with children with healthy diet without vitamin D insufficiency (reference group) and adjusted for age, sex, annual household income, parental history of asthma, BMI z-score, breastfeeding, outdoor physical activity, and early life exposure to second-hand smoke. Dietary pattern: healthy diet (dietary score ≥1) as compared with unhealthy diet (dietary score ≤0). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. BMI, body mass index.

We then conducted an exploratory analysis of vitamin D insufficiency and the binary dietary score, separately in children with atopic asthma and those with nonatopic asthma (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary materials are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ped). In this analysis, an unhealthy diet and vitamin D insufficiency were significantly associated with increased odds of ≥1 hospitalization for asthma in the previous year, both in children with atopic asthma and in children with nonatopic asthma. However, the magnitude of the observed association was ∼9-fold stronger in children with nonatopic asthma than in those with atopic asthma. Whereas similar findings were obtained for ≥1 severe exacerbation among children with atopic asthma, nonsignificant results were obtained for nonatopic asthma.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that a healthy diet—with frequent consumption of vegetables and grains and low consumption of dairy products and sweets—is associated with higher lung function in Puerto Rican children and adolescents without asthma. Moreover, our findings suggest that an unhealthy diet—low in vegetables and grains and high in dairy and sweets—has synergistic detrimental effects with vitamin D insufficiency on severe disease exacerbations in Puerto Rican children with asthma.

A diet derived from fruit and vegetables, rich in antioxidants (vitamins A, C, and E) and ω-3 and ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, has been shown to have favorable effects on pulmonary health.22 Similarly, 2 population-based studies in adults demonstrated that high fiber intake was positively associated with FEV1 and FVC,23 and that a diet high in processed products (high energy intake from fat, snacks, bread, and fast food, but low in micronutrients and fiber) was associated with a lower FEV1 and FVC.24 Moreover, dietary patterns high in refined foods (fat, salty snacks, high-sugar beverages, and low intake of vegetables, fruit, and whole grain) have been associated with an accelerated longitudinal decline in FEV1.25 Data from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study showed that a “prudent” dietary pattern (high consumption of fruit, vegetables, oily fish, and whole-meal cereals) and dietary “total antioxidant capacity” (TAC) are positively associated with lung function, whereas higher processed meat consumption was associated with lower lung function, particularly in men who also consumed less fruits and vegetables or had low dietary TAC.26 Among adult smokers without respiratory disease, a Westernized diet was associated with impaired lung function, whereas a Mediterranean diet was linked to preserved lung function.27

The effect of dietary patterns on lung function or asthma control in children is less clear. Because asthmatic children typically have lower lung function and greater airway inflammation, dietary intake might affect lung function differently among asthmatic and nonasthmatic children. We report that higher dietary score did not affect FEV1 and FVC among asthmatic children, who have airway inflammation and in whom diet alone may not suffice to improve lung function. On the contrary, higher intake of fruit and vegetables, as well as a Mediterranean diet, has been positively associated with FEV1 and FVC, but inversely associated with IL-8 levels in nasal lavage in asthmatic children, but not in healthy controls.28 Such discrepant findings may be explained by different definitions of dietary patterns across studies, and potential residual confounding (eg, by air pollution) in our study. A higher Mediterranean diet score, defined by high frequent consumption of pro-Mediterranean food and low frequent consumption of anti-Mediterranean food, has been associated with lower odds of asthma but not with asthma control or FEV1 among children with asthma.29 In a separate study, a dietary pattern with “high fat, sugar, and salt” was associated with 23% higher odds of emergency visits for asthma, whereas a dietary pattern rich in “fish, fruit, and vegetables” was associated with 16% lower odds of current use of asthma medications.30 To our knowledge, this study is the first to report combined detrimental effects of an unhealthy diet and vitamin D insufficiency on asthma exacerbations, highlighting potential synergistic effect of diverse nutrients and dietary patterns on asthma outcomes. Our findings require validation in larger studies that also examine potential underlying mechanisms.

Dietary components can modulate immune function by regulating T-helper (Th)1 and Th2 (proallergic) immune responses that lead to airway and systematic inflammation,4 but we found no significant association between a dietary score and total or allergen-specific IgE. Animal models show that a diet rich in saturated fatty acids and cholesterol can facilitate airway inflammation mediated by IL-17,31 whereas a diet rich in unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, and fiber can attenuate airway inflammation by promoting Th2 cell responses.32 Epidemiologic studies also show associations between diet, inflammation markers, and lung function. Consumption of a healthy, plant food-based diet has been associated with a significant reduction in C-reactive protein.33 The dietary inflammatory index (DII), a score that categorizes individual diet on a continuum from most anti-inflammatory to most proinflammatory based on FFQs, has been found to be higher in subjects with asthma than in healthy controls. Moreover, higher DII score has been associated with increased odds of asthma and increased IL-6 levels, but decreased FEV1.34 Likewise, we report that dietary score is inversely associated with reduced plasma IL-17F, particularly in healthy controls. We previously reported that a healthier diet (high in vegetables and grains and low in dairy and sweet) is associated with decreased odds of asthma and lower levels of IL-17F in Puerto Rican children, indicating that diet could have beneficial effects by downregulating Th-17 cytokines.13 Of interest, the estimated effect of combined vitamin D insufficiency and an unhealthy diet on hospitalizations for asthma was stronger in children with nonatopic asthma than in children with atopic asthma, further suggesting nonallergic mechanisms (eg, immune modulation of viral illness) for our findings. However, these results must be cautiously interpreted, given small sample size and the exploratory nature of the analysis.

Longitudinal studies or whole-diet interventions are still lacking. Current studies of dietary interventions or weight loss and asthma control have mostly focused on “obese asthma,”35,36 but our findings for lung function and asthma exacerbations were independent of obesity. Although a 16-week randomized control trial of vegetable and fruit concentrates, fish oil, and probiotics significantly improved lung function and reduced the use of asthma medications in school-aged children,37 prospective studies are still needed to evaluate whether change of diet toward healthier pattern improves asthma control and disease outcomes.

This study has considerable strengths, including a study sample representative of children in Puerto Rico, detailed and objective measurement of pertinent phenotypes, and the ability to account for several socioeconomic and lifestyle confounders. We also acknowledge several limitations. First, we cannot determine temporal relationship between dietary patterns and lung function or asthma exacerbations in our cross-sectional study. However, it is unlikely that children with worse lung function or asthma exacerbations would adopt an unhealthy dietary pattern. Second, recall bias and social desirability bias may introduce misclassification of food frequency consumption by the participants' parents. Nonetheless, parental report of FFQ or dietary patterns among young children has been shown to be accurate.38 Third, unmeasured or residual confounding (eg, by air pollution and the gut microbiota) may have affected our results. Confounding by socioeconomic status (SES) is unlikely, as our results were unchanged after adjustment for household income and remained similar in models adjusting for other SES indicators (parental education and type of health insurance). Lastly, the generalizability of our findings in Puerto Ricans to children in other underserved racial or ethnic groups would require further investigation.

In summary, our study in Puerto Rico suggests beneficial effects of healthy dietary patterns on lung function in children without asthma, as well as synergistic detrimental effects of an unhealthy diet and vitamin D insufficiency on severe exacerbations in children with asthma. These results further support the general benefits of a healthy diet in underserved children such as Puerto Ricans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating children and their families for their invaluable contribution to the study. This work was supported by grants HL079966, HL117191, and HL119952 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by The Heinz Endowments. Sponsors had no role in the design of the study, collection of data, data analysis, or in the preparation of the article. Dr. Celedón had full access to all data and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the analysis.

Authors' Contribution

Conception and study design were done by Y.-Y.H., G.C., and J.C.C.; data collection was performed by M.A., A.C.-S., and E.A.-P; data analysis and interpretation were by Y.-Y.H., E.F., and J.C.C.; drafting of the article for intellectual content was done by Y.-Y.H., E.F., and J.C.C. All authors approved the final version of the article before submission.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Asher I, Pearce N. Global burden of asthma among children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18:1269–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006; 368:733–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han YY, Blatter J, Brehm JM, Forno E, Litonjua AA, Celedón JC. Diet and asthma: vitamins and methyl donors. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1:813–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julia V, Macia L, Dombrowicz D. The impact of diet on asthma and allergic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:308–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurmatov U, Devereux G, Sheikh A. Nutrients and foods for the primary prevention of asthma and allergy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:724–733 e721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv N, Xiao L, Ma J. Dietary pattern and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma Allergy 2014; 7:105–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tromp II, Kiefte-de Jong JC, de Vries JH, Jaddoe VW, Raat H, Hofman A, de Jongste JC, Moll HA. Dietary patterns and respiratory symptoms in pre-school children: the Generation R Study. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:681–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berentzen NE, van Stokkom VL, Gehring U, Koppelman GH, Schaap LA, Smit HA, Wijga AH. Associations of sugar-containing beverages with asthma prevalence in 11-year-old children: the PIAMA birth cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015; 69:303–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeChristopher LR, Uribarri J, Tucker KL. Intakes of apple juice, fruit drinks and soda are associated with prevalent asthma in US children aged 2–9 years. Public Health Nutr 2016; 19:123–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey, 2014. In: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, ed. March 1, 2016. ed. Atlanta, GA, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oraka E, Iqbal S, Flanders WD, Brinker K, Garbe P. Racial and ethnic disparities in current asthma and emergency department visits: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 2001–2010. J Asthma 2013; 50:488–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigo-Valentín A, Hodge SR, Kozub FM. Adolescents' dietary habits, physical activity patterns, and weight status in Puerto Rico. Childhood Obes 2011; 7:488–494 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han YY, Forno E, Brehm JM, Acosta-Perez E, Alvarez M, Colon-Semidey A, Rivera-Soto W, Campos H, Litonjua AA, Alcorn JF, Canino G, Celedon JC. Diet, interleukin-17, and childhood asthma in Puerto Ricans. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 115:288–293 e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brehm JM, Acosta-Perez E, Klei L, Roeder K, Barmada M, Boutaoui N, Forno E, Kelly R, Paul K, Sylvia J, Litonjua AA, Cabana M, Alvarez M, Colon-Semidey A, Canino G, Celedon JC. Vitamin D insufficiency and severe asthma exacerbations in Puerto Rican children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186:140–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bird HR, Davies M, Duarte CS, Shen S, Loeber R, Canino GJ. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: II. Baseline prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates in two sites. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1042–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brehm JM, Acosta-Perez E, Klei L, Roeder K, Barmada MM, Boutaoui N, Forno E, Cloutier MM, Datta S, Kelly R, Paul K, Sylvia J, Calvert D, Thornton-Thompson S, Wakefield D, Litonjua AA, Alvarez M, Colon-Semidey A, Canino G, Celedon JC. African ancestry and lung function in Puerto Rican children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:1484–1490 e1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumenthal MN, Banks-Schlegel S, Bleecker ER, Marsh DG, Ober C. Collaborative studies on the genetics of asthma—National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Clin Exp Allergy 1995; 25 Suppl 2:29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabagambe EK, Baylin A, Allan DA, Siles X, Spiegelman D, Campos H. Application of the method of triads to evaluate the performance of food frequency questionnaires and biomarkers as indicators of long-term dietary intake. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 154:1126–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152:1107–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Department of Agriculture. ChooseMyPlate.gov Website, Food Groups Overview; Washington, DC, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MS, Zheng J, Stocks J. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:1324–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han YY, Forno E, Holguin F, Celedon JC. Diet and asthma: an update. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 15:369–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson C, Lyden E, Rennard S, Mannino DM, Rutten EP, Hopkins R, Young R. The relationship between dietary fiber intake and lung function in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13:643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho Y, Chung HK, Kim SS, Shin MJ. Dietary patterns and pulmonary function in Korean women: findings from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2011. Food Chem Toxicol 2014; 74:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Cassano PA, Ocke M, Burney P, Britton J, Smit HA. Patterns of dietary intake and relation to respiratory disease, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, and decline in 5-y forced expiratory volume. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92:408–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okubo H, Shaheen SO, Ntani G, Jameson KA, Syddall HE, Sayer AA, Dennison EM, Cooper C, Robinson SM. Processed meat consumption and lung function: modification by antioxidants and smoking. Eur Respir J 2014; 43:972–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorli-Aguilar M, Martin-Lujan F, Flores-Mateo G, Arija-Val V, Basora-Gallisa J, Sola-Alberich R. Dietary patterns are associated with lung function among Spanish smokers without respiratory disease. BMC Pulm Med 2016; 16:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romieu I, Barraza-Villarreal A, Escamilla-Nunez C, Texcalac-Sangrador JL, Hernandez-Cadena L, Diaz-Sanchez D, De Batlle J, Del Rio-Navarro BE. Dietary intake, lung function and airway inflammation in Mexico City school children exposed to air pollutants. Respir Res 2009; 10:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rice JL, Romero KM, Galvez Davila RM, Meza CT, Bilderback A, Williams DL, Breysse PN, Bose S, Checkley W, Hansel NN. association between adherence to the mediterranean diet and asthma in Peruvian children. Lung 2015; 193:893–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barros R, Moreira A, Padrao P, Teixeira VH, Carvalho P, Delgado L, Lopes C, Severo M, Moreira P. Dietary patterns and asthma prevalence, incidence and control. Clin Exp Allergy 2015; 45:1673–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HY, Lee HJ, Chang YJ, Pichavant M, Shore SA, Fitzgerald KA, Iwakura Y, Israel E, Bolger K, Faul J, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med 2014; 20:54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, Sichelstiel AK, Sprenger N, Ngom-Bru C, Blanchard C, Junt T, Nicod LP, Harris NL, Marsland BJ. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med 2014; 20:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neale EP, Batterham MJ, Tapsell LC. Consumption of a healthy dietary pattern results in significant reductions in C-reactive protein levels in adults: a meta-analysis. Nutr Res 2016; 36:391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wood LG, Shivappa N, Berthon BS, Gibson PG, Hebert JR. Dietary inflammatory index is related to asthma risk, lung function and systemic inflammation in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2015; 45:177–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood LG, Garg ML, Gibson PG. A high-fat challenge increases airway inflammation and impairs bronchodilator recovery in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:1133–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forno E, Celedon JC. The effect of obesity, weight gain, and weight loss on asthma inception and control. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 17:123–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SC, Yang YH, Chuang SY, Huang SY, Pan WH. Reduced medication use and improved pulmonary function with supplements containing vegetable and fruit concentrate, fish oil and probiotics in asthmatic school children: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 2013; 110:145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burrows TL, Warren JM, Colyvas K, Garg ML, Collins CE. Validation of overweight children's fruit and vegetable intake using plasma carotenoids. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17:162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.