Abstract

Objectives

To assess the validity of categorization of chronic hepatitis B viral infection into stages or phases based upon measures of disease activity and viral load, assuming these phenotypes will be useful for prognostication and determining the need for antiviral therapy.

Design

We assessed the phenotype of hepatitis B of 1,390 adult participants enrolled in the Hepatitis B Research Network Cohort Study, using a computer algorithm.

Results

Only 4% were immune tolerant, while 35% had chronic hepatitis B (18% e antigen positive and 17% e antigen negative) while 23% were inactive carriers. Strikingly, 38% of participants did not fit clearly into any one of these groups and were considered indeterminant. The largest subset of indeterminants had elevated serum aminotransferases with low levels of HBV DNA (less than 10,000 iu/ml). Subsequent determination of hepatitis B phenotype on the next available laboratory tests showed that 64% remained indeterminant. These findings call into question the validity of conventional staging of hepatitis B, in large part because of the substantial proportion of patients who do not fit readily into one of the usual stages or phases.

Conclusions

Further studies are needed of the indeterminant category of chronic hepatitis B viral infection, including assessments of whether patients in this group are perhaps in transition to another phase or if they are a distinct phenotype where there is a need to assess liver disease severity and need for antiviral therapy. (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01263587)

Keywords: hepatitis B, phenotype, stages, phases, algorithm

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a frequent, serious human viral infection, affecting nearly 350 million persons worldwide and representing a major cause of morbidity and mortality from end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (1). The natural history of this infection is complex, involving several phases or stages. Patients with higher levels of HBV DNA in serum and more active liver disease (as shown by elevated serum aminotransferase levels) are at higher risk of developing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (2). Treatment, however, is generally recommended only for patients with chronic HBV infection with active liver disease who are more likely to develop cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (3). A high proportion of individuals seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) have inactive or minimally active disease and are at low risk for developing its long-term complications, making treatment of these individuals inadvisable (3).

Several professional societies have published practice guidelines with recommendations on who should be treated based upon virological, serological and biochemical evaluations that allow patients to be classified into one of several patterns of disease (3–5). Various terms have been used for these patterns, including stage and phase – we have used the term phenotype as it does not necessarily imply transition from one phase to another. Antiviral treatment is recommended for those with immune active hepatitis B, while deferral of treatment is suggested for inactive carriers and immune tolerant or high viral load carriers.

Although there is general consensus that the course of chronic HBV infection comprises four phases, definition of these phases (cutoffs for ALT and HBV DNA) varies, and clinicians often use their clinical impression to assess which phase patient is in. Our aim, therefore, was to determine the distribution of phenotypes in a large cohort of North American patients with chronic HBV infection using objective measures. The Hepatitis B Research Network (HBRN) is an NIH-funded clinical network that has enrolled more than 2,000 participants with chronic HBV infection to provide a “pool” of potential participants for other studies, including of treatment (6). This manuscript describes the process for developing a computer algorithm for assigning participants into various phenotypes at baseline, to examine relationships with demographic, biochemical, immunological and epidemiological features and will be used ultimately to identify changes over time and the long-term clinical implications of different HBV phenotypes.

METHODS

Participants were enrolled into one of the HBRN Cohort or Treatment studies, as previously described (6). All participants were seropositive for HBsAg. Major exclusion criteria included current antiviral therapy, hepatic decompensation, known co-infection with human immunodeficiency (HIV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatocellular carcinoma or previous liver transplantation. The HBRN protocols were developed centrally by network investigators but were approved by the institutional review boards of each of the participating institutions, and all participants gave written informed consent. Participants underwent an initial evaluation which included medical history, physical examination and several questionnaires meant to capture dietary habits, alcohol and tobacco use, clinical symptoms and quality of life. Demographic features including age, sex, self-identified race and place of birth were recorded as was the patient’s history of prior antiviral therapy. Participants’ alcohol consumption was estimated using a validated Alcohol Risk Score (6) and was categorized into a) none (fewer than 12 drinks in last 12 months), b) moderate (12 or more drinks in the past year but not in ‘At-risk’ category) or c) at-risk use (7–9).

Blood samples were drawn at baseline and at subsequent visits at 12 and 24 weeks and every 24 weeks thereafter. Routine laboratory testing for complete blood counts and chemistry panels including serum aminotransferase levels was done locally and the results recorded in a central database maintained by the HBRN Data Coordinating Center. Additional serum samples were shipped to a central repository and from there to various laboratories for uniform virologic testing. HBV DNA levels were determined using a real time PCR assay (COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS TaqMan HBV Test, v2.0; Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ). HBV genotype was determined by mass spectrometry at the Molecular Epidemiology and Bioinformatics Laboratory of the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (10). Serum samples from all participants were also tested centrally for anti-HDV using a commercially available enzyme immunoassay (EIA: DiaSorin, Italy). Data on other serological and biochemical parameters including hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), prior serum hepatitis B viral DNA (HBV DNA) levels and prior serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were captured from participants’ medical records and also entered into the database.

Liver biopsies were not routinely done in participants, so estimates of liver disease severity were made using FIB-4 (a parameter calculated using ALT and AST values, platelet count and age) and (APRI) AST to platelet ratio, well validated methods for estimating liver disease severity with a relatively high predictive value for detecting the presence of cirrhosis (11–13).

HBV phenotype designation was based upon previously published definitions (3,11) with some modifications, as follows: Immune tolerant HBV infection was defined by presence of normal serum ALT levels despite the presence of HBeAg and high levels of HBV DNA in serum (≥105 IU/mL). The diagnosis of “immune active” chronic hepatitis B was based on presence of elevated ALT levels and HBsAg accompanied by high levels of HBV DNA (i.e. ≥105 IU/mL for HBeAg-positive and >104 IU/mL for HBeAg-negative patients). The inactive carrier state was defined by presence normal serum ALT levels and HBsAg in serum but absence of HBeAg and with no detectable or only low levels of HBV DNA (≤104 IU/mL). Participants who did not fulfill criteria for any one of these four categories were categorized as having an “indeterminant” phenotype.

Phenotype was calculated using a single ALT and HBV DNA value at or near the baseline study visit, with a computer algorithm. The proportion of participants in each phenotype were compared using two methods of calculation – one in which the upper limit of the normal range (ULN) for ALT was “fixed” (i.e. 30 U/L for men and 20 U/L for women, according to the AASLD Practice Guideline) (3) and the other in which it varied based on the normal range of ALT for the local laboratory. These assigned phenotypes were then also compared to the phenotypes assigned by local physician investigators at baseline based on all laboratory values available to them at that time.

Baseline characteristics were summarized either as frequencies and percentages in the case of categorical variables. The denominator used for the calculation of percentages is the number of participants who have non-missing data, and this number can differ from the maximum possible number shown in the heading: 83% of maximum possible for the anti-HDV test, 89% for both the APRI and FIB-4 scores, 96% for BMI, and > 99% for all other variables. The median was used to describe the average characteristics of a group, with interquartile ranges. To test whether observed differences in baseline characteristics across phenotype groups where statistically significant, we performed Pearson’s chi-squared tests in the case of categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. Comparisons between, or among, subsets of phenotypes were not performed. Agreement between various phenotype determinations was measured with Cohen’s kappa coefficient, a statistic with numerical value between 0 and 1 describes various strengths of agreement: 0–0.20 slight, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 substantial, and 0.81–1 almost perfect (14,15). General associative patterns between ALT and HBV DNA within HBeAg positive and negative subgroups were described with scatterplots using a log10 transformation of HBV DNA as the horizontal axis and a log2 transformation of ALT as the vertical axis. HBV DNA averages in the log2 scale were estimated for all observed values of HBV DNA in the log10 scale, and the resulting moving average line was superimposed on the scatterplots. For all statistical tests, a significance level of 0.05 was used to establish statistical significance. The statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

As of January 26 2015, 2,290 participants had been enrolled into one of the HBRN studies. The current analysis was limited to adults with chronic HBV infection, who were not on antiviral therapy and had undergone a washout period of at least 6 months. The specific reasons for exclusion and numbers in each group are shown in the CONSORT diagram as Supplementary Figure 1a. Among 1,571 adult participants who met all inclusion criteria, 1,390 had sufficient data available to allow a baseline phenotype to be determined (Table 1). Their mean age was 43.0 years (range18 to 80 years) and 51% were male. Asians comprised 72% of the cohort, blacks 14% and whites 11%. Only 1% reported of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Strikingly, only 19% of patients had been born in North America. Of the rest, 83% were born in Asia and 13% in Africa. HBV genotype distribution appeared to reflect place of birth with 64% having HBV genotypes B or C. While 28% of the cohort admitted to consuming alcohol, “at risk” intake was admitted by only 8%. This cohort of 1,390 participants were enrolled in 19 different medical sites across the United States (See Supplementary Table 1) plus a single Canadian site, the University of Toronto, which contributed the highest number of participants (18% of the total).

Table 1.

Demographic, epidemiologic, biochemical and serological characteristics of 1,390 adult participants with chronic hepatitis B

| Characteristic | Feature | Number (proportion) or Median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.1 (18.1–80.2) | |

| Sex | Male | 710 (51%) |

| Race | White | 157 (11%) |

| 999 Black | 199 (14%) | |

| Asian | 995 (72%) | |

| Other | 37 (3%) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 15 (1%) |

| Place of Birth | Africa | 140 (10%) |

| Asia | 923 (67%) | |

| Europe | 43 (3%) | |

| North America | 268 (19%) | |

| Other | 10 (1%) | |

| Alcohol Risk Level | None | 993 (72%) |

| Moderate | 284 (21%) | |

| At-Risk | 105 (8%) | |

| Other Characteristics | Pregnant | 50 (7%) |

| HBV therapy history | Yes | 165 (12%) |

| BMI* (kg/m2) | Median (min-max) | 24.2 (14.8–52.2) |

| Anti-HDV | Positive | 34 (3%) |

| HBV Genotype | A | 222 (16%) |

| B | 467 (34%) | |

| C | 416 (30%) | |

| D | 96 (7%) | |

| Other | 41 (3%) | |

| Not Determined | 148 (11%) |

BMI, body mass index

Table 2 shows the distribution of participants by phenotype. In this adult population, only 4% were categorized as immune tolerant, while 19% had HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B, 17% HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and 23% were classified as inactive carriers. A striking finding was the large proportion of patients who did not fit into any of the four conventional phenotypes. Indeed, the largest single phenotype (38% of the total) was indeterminant when using fixed ALT criteria of ULN of 30 U/L for men and 20 U/L for women. The immune tolerant group (IT) comprised only 57 participants, who were observed to be on average younger in age, less frequently male, almost exclusively of Asian race (98%), more frequently born outside North America (89%) and most frequently infected with HBV genotypes B or C (93%). Patients with chronic hepatitis B with HBeAg were observed to be younger than those without (median age = 37 vs 46 years), infected with HBV genotype C somewhat more frequently (45% vs 27%) and with genotype B less frequently (31% vs 49%). Participants with chronic hepatitis B had biochemical markers of more severe liver disease, including higher serum aminotransferases and a larger number had APRI and FIB-4 scores in the highest stratum than subjects with other phenotype designations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of adult participants in each of the protocol-defined phases or phenotypes of chronic hepatitis B

| Characteristic | Feature | Immune Tolerant |

Chronic Hepatitis B | Inactive Carrier | Indeterminant | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg + | HBeAg − | ||||||

| No. | 57 | 258 | 233 | 318 | 524 | ||

| Age (years) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 31 (25.6–37.2) | 37 (27.1–44.7) | 46 (37.3–53.0) | 46 (36.8–55.2) | 42 (34.8–52.7) | <0.0001 |

| Gender | Male | 21 (37%) | 131 (51%) | 142 (61%) | 170 (54%) | 246 (47%) | 0.0012 |

| Race | White | 1 (2%) | 22 (9%) | 18 (8%) | 31 (10%) | 85 (16%) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 19 (7%) | 22 (9%) | 73 (23%) | 85 (16%) | ||

| Asian | 56 (98%) | 209 (81%) | 189 (81%) | 206 (65%) | 335 (64%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 8 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 18 (3%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 0.03 |

| Place of birth | Africa | 0 (0%) | 8 (3%) | 16 (7%) | 51 (16%) | 65 (12%) | <0.0001 |

| Asia | 51 (89%) | 188 (73%) | 177 (76%) | 186 (59%) | 321 (61%) | ||

| Europe | 0 (0%) | 4 (2%) | 6 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 23 (4%) | ||

| North America | 6 (11%) | 57 (22%) | 32 (14%) | 66 (21%) | 107 (20%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Alcohol Risk Level | None | 41 (72%) | 187 (73%) | 170 (74%) | 228 (72%) | 367 (70%) | n.s.*** |

| Moderate | 12 (21%) | 48 (19%) | 45 (19%) | 68 (22%) | 111 (21%) | ||

| At-Risk | 4 (7%) | 22 (9%) | 16 (7%) | 20 (6%) | 43 (8%) | ||

| Other Characteristics | Pregnant | 10 (28%) | 12 (9%) | 3 (3%) | 9 (6%) | 16 (6%) | <0.0001 |

| HBV therapy history | Yes | 7 (12%) | 33 (13%) | 27 (12%) | 33 (10%) | 65 (12%) | n.s.*** |

| BMI* (kg/m2) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 22.4 (20.0–24.9) | 23.7 (21.1–26.3) | 23.9 (22.1–26.7) | 24.6 (21.9–27.8) | 25.0 (22.1–28.0) | <0.0001 |

| Anti-HDV | Positive | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 5 (2%) | 24 (6%) | 0.001 |

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 8.3 (7.9–8.6) | 8.1 (7.0–8.4) | 5.0 (4.6–5.7) | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 2.9 (2.1–3.5) | <0.0001 |

| ALT (U/L) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 18 (15–23) | 54 (36–93) | 52 (35–80) | 19 (16–23) | 34 (25–44) | <0.0001 |

| AST (U/L) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 22 (18–24) | 39 (28–56) | 36 (29–49) | 21 (18–25) | 27 (23–34) | <0.0001 |

| APRI** | <=0.50 | 52 (98%) | 131 (54%) | 111 (55%) | 264 (95%) | 367 (80%) | <0.0001 |

| >0.50–2.0 | 1 (2%) | 93 (38%) | 75 (37%) | 13 (5%) | 88 (19%) | ||

| >2.0 | 0 (0%) | 19 (8%) | 15 (7%) | 1 (0%) | 5 (1%) | ||

| FIB-4 | <1.45 | 47 (89%) | 186 (77%) | 134 (67%) | 221 (79%) | 369 (80%) | 0.0009 |

| 1.45–3.25 | 6 (11%) | 44 (18%) | 58 (29%) | 53 (19%) | 78 (17%) | ||

| >3.25 | 0 (0%) | 13 (5%) | 9 (4%) | 4 (1%) | 13 (3%) | ||

| HBV Genotype | A | 2 (4%) | 37 (14%) | 30 (13%) | 53 (17%) | 100 (19%) | <0.0001 |

| B | 18 (32%) | 81 (31%) | 114 (49%) | 98 (31%) | 156 (30%) | ||

| C | 35 (61%) | 116 (45%) | 62 (27%) | 75 (24%) | 128 (24%) | ||

| D | 0 (0%) | 12 (5%) | 15 (6%) | 25 (8%) | 44 (8%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 5 (2%) | 8 (3%) | 8 (3%) | 20 (4%) | ||

| Not determined | 2 (4%) | 7 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 59 (19%) | 76 (15%) | ||

BMI, body mass index;

APRI, AST to platelet ratio,

n.s. not significant

A large proportion of those enrolled in the HBRN cohort study were classified as inactive carriers (n=318, 23%). The demographic features of inactive carriers appeared to be not substantially different than participants in other categories except that it included more blacks than were in any of the other phenotypes (23%). Their ALT and HBV DNA levels were, by definition, lower than in other groups, and importantly the indirect markers of disease stage and fibrosis (FIB-4 and APRI) were generally low with only 1% having values suggestive of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. Finally, the largest group of patients (n=524, 38%) were classified as indeterminant. The indeterminant group did not appear to be clearly different from the cohort as a whole with regard to sex, age, race, place of birth and alcohol risk. Although the presence of anti-HDV was infrequent overall, it was observed to be highest in this group (6% vs 1% overall).

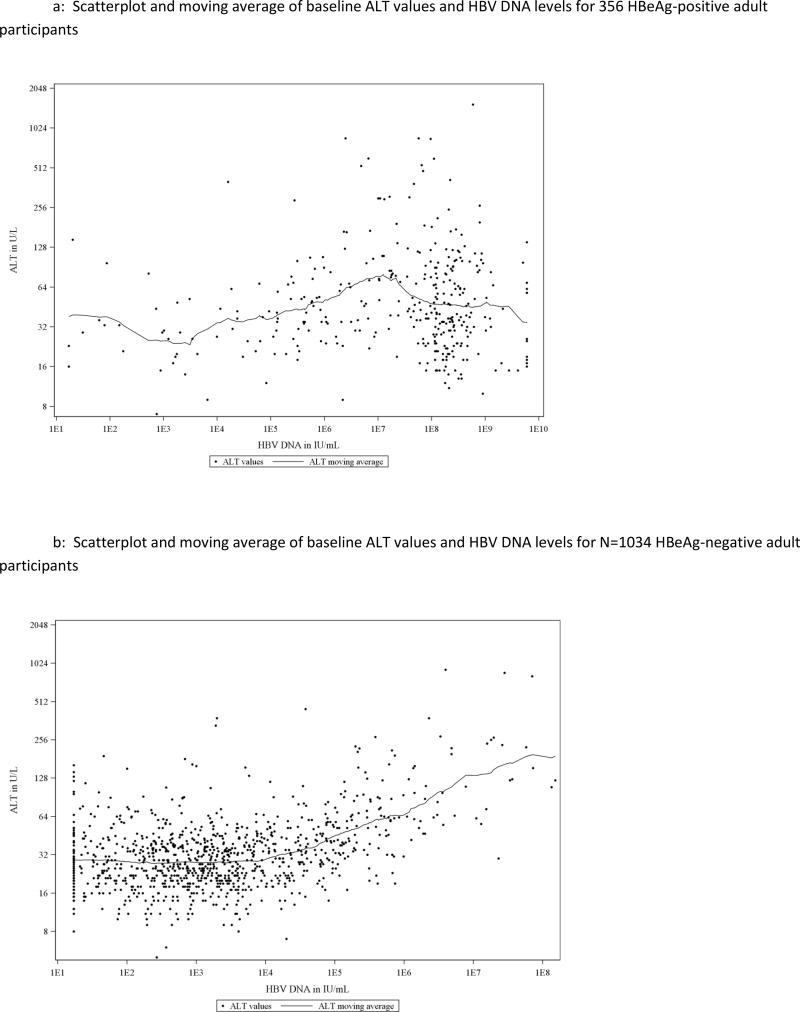

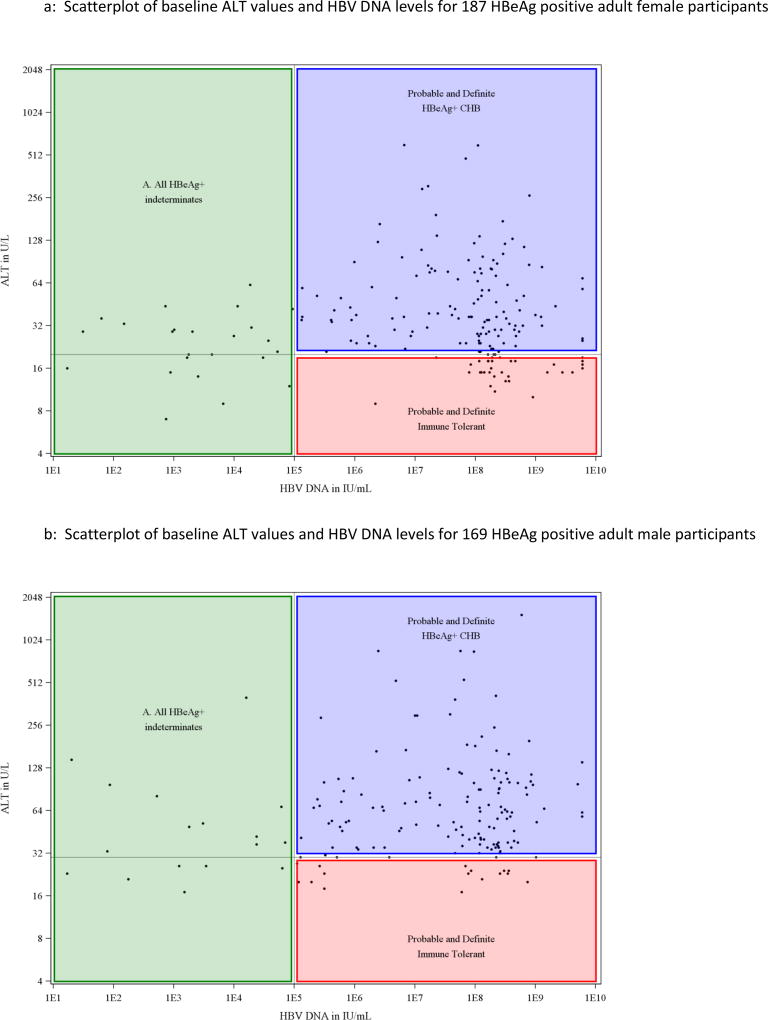

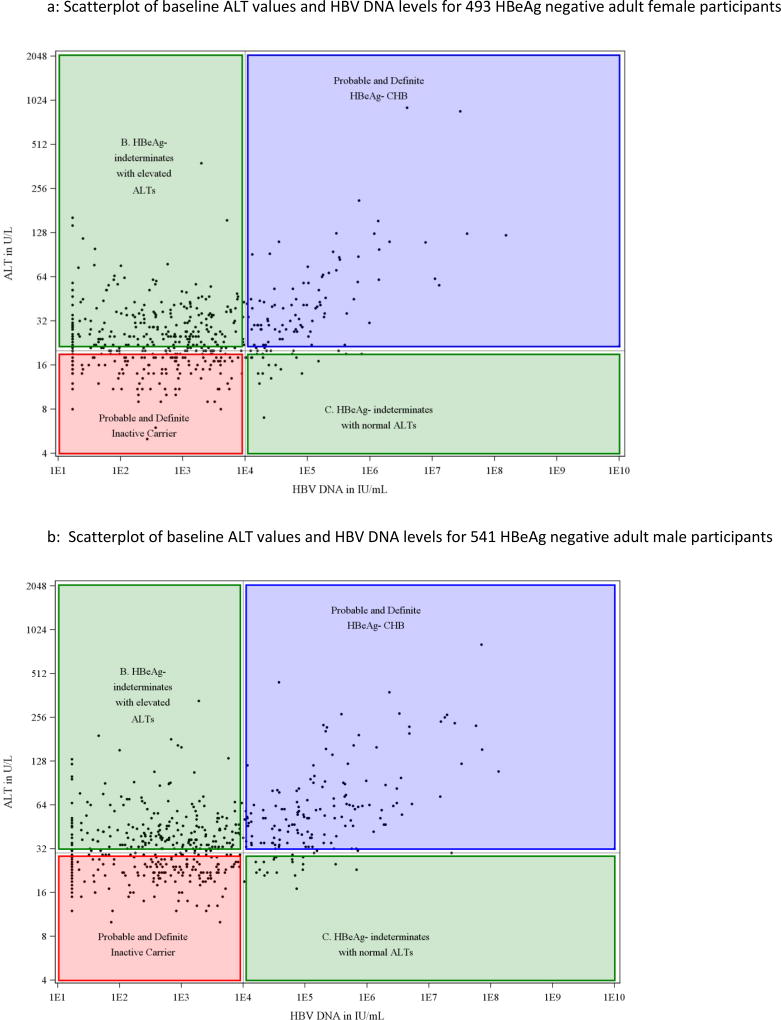

Serum ALT levels at baseline for all individual participants were plotted against their HBV DNA values (Figure 1). Among HBeAg positive participants, there was not an apparent linear association between ALT and HBV DNA (Figure 1a, Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.10, p=0.06) but in the HBeAg-negative cohort, ALT levels appeared to rise progressively with HBV DNA values above 104 IU/mL (Figure 1b: correlation coefficient = 0.41, p<0.0001). For serum HBV DNA levels up to 104 IU/mL (the apparent inflection point in the HBeAg-negative group), the correlation coefficient was −0.01 (p=0.78) while above that level it was 0.58 (p<0.0001). Separate scatterplots of ALT vs HBV DNA were then created for men and women using the fixed cutoff for normal ALT for each of these groups shown as a horizontal line and HBV DNA cutoffs as a vertical line (Figures 2 and 3). This display allowed each participant to be fitted into one of the conventional HBV phenotypes and demonstrated that a large number were indeterminant for both men and women.

Figure 1.

A: Scatterplot and moving average of baseline ALT values and HBV DNA levels for 356 HBeAg-positive adult participants

B: Scatterplot and moving average of baseline ALT values and HBV DNA levels for N=1034 HBeAg-negative adult participants

Figure 2.

A: Scatterplot of baseline ALT values and HBV DNA levels for 187 HBeAg positive adult female participants

B: Scatterplot of baseline ALT values and HBV DNA levels for 169 HBeAg positive adult male participants

Figure 3.

A: Scatterplot of baseline ALT values and HBV DNA levels for 493 HBeAg negative adult female participants

B: Scatterplot of baseline ALT values and HBV DNA levels for 541 HBeAg negative adult male participants

Using HBeAg, ALT and HBV DNA results, three separate groups were discernible, referred to as indeterminant A, B and C. The indeterminant A group comprised 41 subjects who were HBeAg positive but had HBV DNA levels below 105 IU/mL. Their serum ALT levels were raised in 25 (61%), but generally only modestly (median=29 U/L, and less than twice the upper limit of normal in 78%). The indeterminant B phenotype included the largest number of participants (n=433; 83%) and was defined by lack of HBeAg and low levels of HBV DNA (≤104 IU/mL) but raised ALT values (median 36 U/L, range 21 to 380 U/L). The indeterminant C cohort comprised 50 individuals who lacked HBeAg and had normal ALT levels but moderate-to-high concentrations of HBV DNA (median 4.49, range 4.0–7.4 log10 IU/mL).

The demographic and clinical features of the three indeterminant groups are compared in Table 3. Participants in the indeterminant A phenotype group (HBeAg positive low viral load) were slightly younger than those in the other indeterminant groups, but younger age is characteristic of HBeAg-positive versus -negative subjects as a whole. Importantly, few participants with an indeterminant phenotype had cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis as indicated by FIB-4 or APRI scores. These surrogate markers of liver disease severity were not significantly different among the three indeterminant groups.

Table 3.

Subset of participants in Table 2 with indeterminate phenotype (calculated): Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Feature | Indeterminant A |

Indeterminant B |

Indeterminant C |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=41 | N=433 | N=50 | |||

| Age (years) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 37.5 (30.2–46.7) | 42.4 (35.2–52.5) | 44.5 (36.0–55.0) | 0.02 |

| Gender | Male | 17 (41%) | 206 (48%) | 23 (46%) | n.s. |

| Race | White | 9 (22%) | 74 (17%) | 2 (4%) | 0.051 |

| Black | 5 (12%) | 75 (17%) | 5 (10%) | ||

| Asian | 24 (59%) | 270 (63%) | 41 (82%) | ||

| Other | 3 (7%) | 13 (3%) | 2 (4%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 8 (2%) | 0 (0%) | n.s. |

| Place of birth | Africa | 4 (10%) | 57 (13%) | 4 (8%) | 0.06 |

| Asia | 21 (51%) | 260 (60%) | 40 (82%) | ||

| Europe | 2 (5%) | 21 (5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| North America | 14 (34%) | 88 (20%) | 5 (10%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 6 (1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Alcohol Risk Level | None | 26 (65%) | 303 (70%) | 38 (76%) | n.s. |

| Moderate | 8 (20%) | 92 (21%) | 11 (22%) | ||

| At-Risk | 6 (15%) | 36 (8%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Other Characteristics | Pregnant | 3 (13%) | 12 (5%) | 1 (4%) | n.s. |

| HBV therapy history | Yes | 7 (17%) | 51 (12%) | 7 (14%) | n.s. |

| BMI* (kg/m2) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 24.8 (21.9– 27.6) | 25.1 (22.4–28.4) | 23.2 (21.6–25.9) | 0.02 |

| Anti-HDV | Positive | 5 (15%) | 19 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.02 |

| HBV DNA (log10 iu/mL | Median (Q1–Q3) | 3.3 (2.9–4.3) | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 4.5 (4.3–4.9) | <0.0001 |

| ALT (U/L) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 29 (20–42) | 36 (29–46) | 20 (18–25) | <0.0001 |

| AST (U/L) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 29 (23–37) | 28 (23–35) | 22 (18–25) | <0.0001 |

| APRI** | <=0.50 | 25 (66%) | 301 (79%) | 41 (98%) | 0.01 |

| >0.50–2.0 | 12 (32%) | 75 (20%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| >2.0 | 1 (3%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| FIB-4 | <1.45 | 26 (68%) | 308 (81%) | 35 (83%) | n.s. |

| 1.45–3.25 | 10 (26%) | 61 (16%) | 7 (17%) | ||

| >3.25 | 2 (5%) | 11 (3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| HBV Genotype | A | 9 (22%) | 85 (20%) | 6 (12%) | 0.004 |

| B | 8 (20%) | 119 (27%) | 29 (58%) | ||

| C | 15 (37%) | 106 (24%) | 7 (14%) | ||

| D | 3 (7%) | 37 (9%) | 4 (8%) | ||

| Other | 1 (2%) | 18 (4%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Not determined | 5 (12%) | 68 (16%) | 3 (6%) |

BMI, body mass index;

APRI, AST to platelet ratio

To determine whether indeterminant phenotypes might represent individuals in transition from one of the conventional phases to another, phenotype was recalculated using the next available set of laboratory values (Table 5). Repeat laboratory results for ALT and HBV DNA levels were available from 1,112 adult participants. Overall, the assignment to a specific phenotype did not change in 818 patients (74%), the stability being greatest for HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B (87%), intermediate for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (78%) and indeterminant A (78%), minimally less for inactive carriers (70%), immune tolerant patients (67%) and indeterminant B (HBeAg negative, elevated ALT) (71%) but considerably less for those in the indeterminant C group (HBeAg negative, high viral load) (32%: p<0.0001), the HBeAg negative patients with moderate levels of HBV DNA but normal serum ALT levels.

Table 5.

Stability of phenotype calculation when repeated 4–40 (median 14) weeks after HBRN enrollment.

| Total | Immune Tolerant |

Chronic Hepatitis B | Inactive Carrier |

Indeterminant. A |

Indeterminant. B |

Indeterminant. C |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg + | HBeAg − | |||||||

| 1390 | 57 | 258 | 233 | 318 | 41 | 433 | 50 | |

| No. with repeat lab data | 1112 | 46 | 202 | 194 | 244 | 32 | 353 | 41 |

| Proportion with unchanged phenotype | 818 74% | 31 67% | 176 87% | 151 78% | 171 70% | 25 78% | 251 71% | 13 32% |

To assess the impact of the low cutoff used to define normal ALT values (<30 U/L for men and <20 U/L for women), the computer algorithm was rerun using reported ULN for local laboratories, which in this study ranged from 24 to 78 U/L for men and women (median 48 U/L). As might be expected, the indeterminant phenotype was less common (see table 5; 22% vs 38%) and the inactive carrier state more frequent (30% vs. 17%) using the local ULN definition. Objective determinations of phenotype based upon specific laboratory values were compared to the semi-subjective determination made by the enrolling principal investigator (Table 4). The subjective assessments were more likely to place participants into a conventional phenotype, the proportion of cases designated as indeterminant being 13% by the physician investigator compared to 38% by computer using fixed ALT ULN values and 22% by computer using locally defined ALT ULN values.

Table 4.

Agreement Between Physician Assigned and Calculated Phenotypes (Using Fixed or site specific ULN)

| Calculated Phenotype |

Physician Assigned Phenotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using Fixed ULN |

IT | HBeAg+ Active |

HBeAg− Active |

Inactive | Indeterminant | All | Kappa correlation coefficient |

| Immune Tolerant | 44 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 57 | Κ=0.39 95% CI=(0.36,0.42) |

| HBeAg+ CHB | 63 | 173 | 7 | 1 | 14 | 258 | |

| HBeAg− CHB | 7 | 6 | 162 | 22 | 36 | 233 | |

| Inactive carrier | 7 | 1 | 49 | 236 | 25 | 318 | |

| Indeterminant | 12 | 13 | 152 | 246 | 100 | 523 (of 524) | |

| Using Site Specific ULN | |||||||

| Immune Tolerant | 92 | 50 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 161 | =0. 47 5% CI=(0.44,0.51) |

| HBeAg+ CHB | 15 | 130 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 154 | |

| HBeAg− CHB | 1 | 5 | 115 | 2 | 8 | 131 | |

| Inactive carrier | 12 | 1 | 131 | 422 | 72 | 638 (of 639) | |

| Indeterminant | 13 | 14 | 117 | 80 | 81 | 305 | |

| All | 133 | 200 | 371 | 506 | 179 | 1389 | |

DISCUSSION

The relative risk for individuals with chronic HBV infection of developing progressive liver disease and HCC varies greatly, based largely on disease activity and level of viral replication and may be predicted by their phenotype (17–23). Although these broad categories have been characterized as “phases” or “stages” there is little evidence that individual patients pass through each of these sequentially. However, transitions from one phase to another, and back, are well described, such as “seroconversion” in which HBeAg is lost, often associated with a decrease in serum HBV DNA levels and reduction in aminotransferase activity (24–26). Reactivation may also occur, typically in association with immune suppression for various reasons or sometimes simply spontaneously (27). Variability in phenotype definitions has been exaggerated by technical advances over time in the assays used to measure HBV DNA with improvements in sensitivity and dynamic range, as well as variability in what is considered to be normal for serum ALT activity (28,29). Furthermore, much of the data upon which the description of these phases is based has been derived from studies done in Asia (30).

HBRN patients were enrolled into a large registry with the goal of tracking serological and biochemical changes over time. The cohort excluded patients who were currently or recently on antiviral treatment and could therefore have under-represented those with the active phenotypes and over-represented immune tolerant and inactive carrier phenotypes. This limitation notwithstanding, the clinical features of the four conventional phenotypes can be compared. Strikingly, the immune tolerant phenotype was uncommon (only 4%) and was limited to Asian patients, generally in the younger age groups. Original descriptions of the immune tolerant phase of chronic HBV infection came from Asia (30) and it appears may not particularly apply to Western populations although it is not clear what factors might account for this. With regard to HBV genotype, genotype C was the most frequent in this cohort and was somewhat over-represented among the immune tolerant participants (61%), consistent with previous reports that genotype C is associated with delay in HBeAg seroconversion (31). Among the three indeterminant groups, genotype B was most common in the group with HBeAg negative but high HBV DNA levels (indeterminant C, 58%) while genotype C was the most frequent among participants with HBeAg and low HBV DNA levels (indeterminant A, 37 (31).

One of the key findings from our data and perhaps the most surprising was the relatively large number of individuals who did not fit neatly into one of the well-described phenotypes. The AASLD Practice Guideline on management of Hepatitis B includes a description of individuals with serum ALT 1 to 2 times the upper limit of normal and serum HBV DNA values between 2,000 and 20,000 (3). This guideline does not provide a name for this “in between” group of patients but does recommend regular monitoring and consideration for liver biopsy. We refer to these individuals as being indeterminant and found them to be the most frequent phenotype (38% overall when using fixed ALT values). This is similar to the proportion of patients found to be “undetermined” in a study of a smaller cohort of Asian Americans (32). It appears that current thinking about HBV infection is an oversimplification and does not match with the diversity of disease expression (33). Three distinct patterns of indeterminant hepatitis B could be determined and the significance of each of these patterns will need to be clarified, particularly with regard to their natural history and whether these patients should be offered antiviral therapy.

It is possible too that the use of a fixed low value to define normal ALT value may have artificially inflated the size of the indeterminant group, but this issue still persists even when using laboratory-specific definition of normal ALT. There has been some controversy about what is thought to represent the normal range for ALT levels (34). Typically these are determined by each local laboratory and might vary based on the equipment used to measure ALT and on the prevalent ALT levels among the normal control subjects used to calibrate the assay at that site. The fixed values of 30 U/L and 20 U/L respectively for men and women have been adopted as a part of the AASLD practice guideline on management of hepatitis B (3), but the use of these numbers clearly affects the determination of phenotype for many patients. A similar observation was made by Hsu and colleagues (32) who looked at the disease phases of patients with chronic hepatitis B and found a very different distribution of phases (or phenotypes) according to whether an upper limit of normal for ALT of 40 U/L was used compared to the standardized values of 30 U/L for men and 20 U/L for women. Lai and colleagues studied approximately 200 patients with chronic hepatitis B and evaluated the severity of their underlying liver disease based on serum ALT activities (34). They found that 37% of patients with persistently normal ALTs had significant liver disease on biopsy. They further divided patients with normal ALT into those with values from 0–25 U/L and 26–40 U/L and again found that the degree of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis was somewhat less among those with ALTs <25.

To establish whether other co-existent forms of liver disease might explain some of the indeterminants, particularly those with elevated ALTs but low HBV DNA levels, we evaluated HDV infection, obesity (as a possible indicator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) and alcohol consumption. Thus, anti-HDV was more frequent in the indeterminant group (6%) than the conventional phenotypes (1%), but was present in only 19 of the 433 indeterminant B group. Similarly, at-risk alcohol intake, pregnancy and obesity were not significantly more frequent in the indeterminant groups compared to the entire cohort. Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 affected 76 (18%) of the indeterminant B phenotype group (low HBV DNA, elevated ALT), compared to 163 (12%) overall. There were no obvious differences in alcohol consumption among participants in the various phenotypes. There were a few indeterminant B participants who were pregnant at baseline and the pregnant state is well known to cause disruptions to otherwise stable HBV infection (34).

Another interesting finding that emerged from this study is the fairly substantial discrepancy between the formal calculated phenotype for each participant and what the local clinician investigator thought it should be. Clinicians were much more likely to categorize patients into one of the well-defined phenotypes. One possible reason for this is the relative novelty of the indeterminant terminology, something that has not been widely used in clinical practice or research up until now. Again, it is not clear whether the computer algorithm or physicians’ impression gives a better representation of the patient’s status or risk of liver disease progression – this may only be determined over time but researchers and the writers of practice guidelines will need to take this issue into account in the meantime.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Flow of patients enrolled in the HBRN Cohort Study and included in this analysis of HBv phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The HBRN was funded by a U01 grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to the following investigators Lewis R. Roberts, MB, ChB, PhD (DK 082843), Anna Suk-Fong Lok, MD (DK082863), Steven H. Belle, PhD, MScHyg (DK082864), Kyong-Mi Chang, MD (DK082866), Michael W. Fried, MD (DK082867), Adrian M. Di Bisceglie, MD (DK082871), William M. Lee, MD (U01 DK082872), Harry L. A. Janssen, MD, PhD (DK082874), Daryl T-Y Lau, MD, MPH (DK082919), Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc (DK082923), Steven-Huy B. Han, MD (DK082927), Robert C. Carithers, MD (DK082943), Norah A. Terrault, MD, MPH (U01 DK082944), an interagency agreement with NIDDK: Lilia M. Ganova-Raeva, PhD (A-DK-3002-001) and support from the intramural program, NIDDK, NIH: Marc G. Ghany, MD. Additional funding to support this study was provided to Kyong-Mi Chang, MD, the Immunology Center, (NIH/NIDDK Center of Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases P30DK50306, NIH Public Health Service Research Grant M01-RR00040), Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc (UL1TR000058, NCATS (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH), Norah A. Terrault, MD, MPH (CTSA Grant Number UL1TR000004), Michael W. Fried, MD (CTSA Grant Number UL1TR001111), and Anna Suk-Fong Lok (CTSA Grant Number UL1RR024986.) Additional support was provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc. and Roche Molecular Systems via a CRADA through the NIDDK.

ROLE OF THE SPONSOR

NIDDK (NIH) provided financial support for each of the clinical centers and a data coordinating center though grants (UO1’s). NIDDK project officers participate in meetings of the network investigators and offer suggestions on data analysis. Dr Hoofnagle is an NIDDK official and is also a co-author on this manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Adrian Di Bisceglie, Manuel Lombardero, Jeffrey Teckman, Lewis Roberts, Harry Janssen, Steven Belle and Jay Hoofnagle were involved in conceptualizing this manuscript, based on data collected by the Hepatitis B research Network (HBRN), reviewing the data, reviewing drafts of the manuscript and giving final approval to the manuscript prior to submission. In addition Adrian Di Bisceglie was responsible for writing the first draft of the manuscript, Manuel Lombardero was the primary person responsible for data analysis and statistical support.

DISCLOSURES

No authors have any relevant financial disclosures or other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, et al. T. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis B. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150:104–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: A 2012 update. Hepatology International. 2012;6:531–61. doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghany MG, Perrillo R, Li R, Belle SH, Janssen HLA, Terrault NA, et al. Characteristics of Adults in the Hepatitis B Research Network in North America Reflect Their Country of Origin and Hepatitis B Virus Genotype. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994, NHANES III Household Adult Data File. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. National Center for Health Statistics. Public use data file documentation number 77560. [Google Scholar]

- 8.http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

- 9.Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college student: what's five drinks? Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:287–291. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganova-Raeva L, Ramachandran S, Honisch C, et al. Robust hepatitis B virus genotyping by mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4161–4168. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00813-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok ASF. Management of hepatitis B: Summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45:1056–1075. doi: 10.1002/hep.21627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, et al. FIB-$: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and FibroTest. Hepatology. 2007;46:32–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.21669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin WG, Park SH, Jang MK, et al. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ration (APRI) can predict liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis. 2008:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple non-invasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Chen CL, et al. Risk Stratification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hepatitis B Virus e Antigen-Negative Carriers by Combining Viral Biomarkers. J Infect Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan HL, Wong VW, Tse AM, et al. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen quantitation can reflect hepatitis B virus in the liver and predict treatment response. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1462–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaroszewicz J, Serrano BC, Wursthorn K, et al. Hepatitis b surface antigen (HBsAg) levels in the natural history of hepatitis b virus (HBV)-infection: A European perspective. J Hepatol. 2010;52:514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broderick AL, Jonas MM. Hepatitis B in children. Semin Liver Disease. 2003;23:59–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volz T, Lutgehetmann M, Wachtler P, et al. Impaired intrahepatic hepatitis B virus productivity contributes to low viremia in most HBeAg-negative patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:843–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong MJ, Trieu J. Hepatitis B inactive carriers: clinical course and outcomes. J Digestive Dis. 2013;14:311–7. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu CM, Hung SJ, Lin J, Tai DI, Liaw YF. Natural history of hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion in patients with normal serum aminotransferase levels. Am J Med. 2004;116:829–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu C-M, Hung S-J, Lin J, Tai D-I, Liaw Y-F. Natural history of hepatitis B e antigen to antibody conversion in patients with normal serum aminotransferase levels. Am J Med. 2004;116:829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in Taiwanese hepatitis B carriers. Journal of Medical Virology. 2004;72:363–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoofnagle JH. Reactivation of hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:S156–SA165. doi: 10.1002/hep.22945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunetto MR, Oliveri F, Coco B, et al. Outcome of anti-HBe positive chronic hepatitis B in alpha-interferon treated and untreated patients: a long term cohort study. J Hepatol. 2002;36:263–70. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chudy M, Hanschmann KM, Kress J, Nick S, Campos R, Wend U, Gerlich W, Nubling CM. First WHO International Reference Panel containing hepatitis B virus genotypes A-G for assays of the viral DNA. J Clin Virol. 2012;55:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tseng T-C, Kao J-H. Treating immune-tolerant hepatitis B. J Viral hepatitis. 2015;22:77–84. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wai CT, Chu C-J, Hussain M, Lok ASF. HBV genotype B is associated with better response to interferon therapy in HBeAg(+) chronic hepatitis than genotype C. Hepatology. 2002;36:1525–1430. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu Y-N, Pan CQ, Abbasi A, Xia V, Bansal R, Hu K-Q. Clinical presentation and disease phases of chronic hepatitis B using conventional versus modified ALT criteria in Asian Americans. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:865–871. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yapali S, Talaat N, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: Our practice and how it relates to the guidelines. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2014;12:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai M, Hyatt BJ, Nasser I, Curry M, Afdhal NH. The clinical significance of persistently normal ALT in chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2007;47:760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borgia G, Carleo MA, Gaeta GB, Gentile I. Hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4677–4683. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i34.4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Flow of patients enrolled in the HBRN Cohort Study and included in this analysis of HBv phenotypes.