Abstract

The quest for a reliable means to detect cannabis intoxication with a breathalyzer is ongoing. To design such a device, it is important to understand the fundamental thermodynamics of the compounds of interest. The vapor pressures of two important cannabinoids, cannabidiol (CBD) and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), are presented, as well as the predicted normal boiling temperature (NBT) and the predicted critical constants (these predictions are dependent on the vapor pressure data). The critical constants are typically necessary to develop an equation of state (EOS). EOS-based models can provide estimations of thermophysical properties for compounds to aid in designing processes and devices. An ultra-sensitive, quantitative, trace dynamic headspace analysis sampling called porous layered open tubular-cryoadsorption (PLOT-cryo) was used to measure vapor pressures of these compounds. PLOT-cryo affords short experiment durations compared to more traditional techniques for vapor pressure determination (minutes versus days). Additionally, PLOT-cryo has the inherent ability to stabilize labile solutes because collection is done at reduced temperature. The measured vapor pressures are approximately 2 orders of magnitude lower than those measured for n-eicosane, which has a similar molecular mass. Thus, the difference in polarity of these molecules must be impacting the vapor pressure dramatically. The vapor pressure measurements are presented in the form of Clausius-Clapeyron (or van’t Hoff) equation plots. The predicted vapor pressures that would be expected at near ambient conditions (25 °C) are also presented.

Keywords: cannabidiol (CBD), headspace (HS), porous layer open tubular-cryoadsorption (PLOT-cryo), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)

1. Introduction

1.1 Cannabis

Cannabis is currently a Schedule 1 drug (illegal under federal law). In recent years, however, there has been a shift in some local or state policies towards the decriminalization of cannabis use. Decreased criminalization may lead to an increase in cannabis use and cannabis-related harm.[1, 2] Potentially negative impacts include: a rise in intoxicated drivers and workers, an increase in cannabis use among adolescents, and negative health effects from chronic cannabis use.[3–7] Unlike alcohol consumption, which can be detected by monitoring the concentration of ethanol in the blood or breath, determination of cannabis intoxication is not as straightforward.

The cannabis plant contains over 500 compounds, including more than 100 plant cannabinoids that have been isolated and identified.[8–10] Some of these plant cannabinoids impart therapeutic or psychoactive affects, e.g., cannabidiol (CBD) and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), respectively.[11] CBD is thought to effect pain sensation and mood but very little research substantiating these claims exist. Because of its psychoactive properties, Δ9-THC is a molecule of great interest in the research and law enforcement communities. However, there are several aspects of the compound Δ9-THC that make collecting and analyzing it in bodily fluids complex. For one, Δ9-THC is rapidly metabolized in the body into both a psychoactive (the hydroxylated metabolite) and a non-psychoactive (the carboxylated metabolite) compound. Δ9-THC is excreted in the urine as a glucuronic acid conjugate. Additionally, a small portion of Δ9-THC is stored in adipose tissue and is released slowly over long time periods (hours, days, weeks). Δ9-THC levels also depend on the mode of consumption (smoking versus eating),[12] when the user consumed,[13] whether or not they are a chronic, an occasional, or a first time user,[14] and of course, what body fluid is sampled.[15] In lieu of these complexities, some countries and states have set legal limits of Δ9-THC concentrations in the blood, including zero tolerance laws to established impairment.

One major problem in addressing potential public health impacts of cannabis use is the lack of a noninvasive testing method to determine use, impairment, and intoxication. The most common methods for determining cannabis usage detect Δ9-THC.[6, 7, 12–21] Devices that detect Δ9-THC in the breath are currently being developed and have many advantages. Breath sampling is attractive because it is non-invasive, can be portable, and has been shown to indicate recent use within 0.5 hours to 2 hours.[17] Impairment, however, may last longer than can be observed by examining the exhaled vapors.[17] The ultimate goal for breath testing of Δ9-THC is correlating Δ9-THC concentrations in the breath to concentration in the blood, and thus, a potential determination of impairment, but the science for this correlation is still lacking.

To provide law enforcement personnel with the best breathalyzer for Δ9-THC detection, a three-pronged research approach has been developed. First, fundamental data and models necessary for developing a Δ9-THC breathalyzer will be provided; material properties for choosing the best materials for “catch” and “release” of Δ9-THC will be investigated; and research into the chemical signature of breath that corresponds with cannabis intoxication will be conducted with “breatholomics” efforts. This approach is collaborative, and each prong is necessary for (and enables) the other efforts. For example, in order to develop the measurement science necessary to obtain fundamental data measurements and develop useful models, material properties will be characterized. Additionally, the chemical signature of the breath while intoxicated from cannabis usage will dictate which compounds require fundamental data measurements and where to focus modeling efforts. Collecting this chemical signature will require advances in material design and apparatus development. The focus of this work is fundamental data and models, specifically vapor pressure measurements.

1.2. Vapor Pressure

Vapor pressure is the very first thing needed to begin a rudimentary equation of state (EOS). An EOS is necessary to provide an avenue for predicting thermophysical properties that are important for designing and engineering a specialized device such as a cannabis breathalyzer. Vapor pressure measurements can be used to predict the normal boiling temperature (NBT, temperature that the fluid boils at 1 atm), which can then be used to predict the critical constants (critical temperature, critical pressure and critical volume). The uncertainty of calculations from these models is of course dependent on the uncertainty of the input data; more data and lower uncertainty is always desirable. For cannabinoids, there are no available data, thus these will be the first available measurements for the field. Well-developed models like standard reference equations are based on hundreds of measurements, whereas the models developed here are a rudimentary beginning but are far better than “chemical intuition” for predicting the important thermophysical properties for device optimization.

Most commercial methods for measuring vapor pressure are designed to measure volatile or moderately volatile compounds. These methods typically require day to weeks to collect sample and can require large sample sizes. A previously developed technique employing porous layer open tubular-cryoadsorption (PLOT-cryo) technology made vapor pressure measurements of cannabinoids possible [22, 23].

1.2 PLOT-cryoadsorption (PLOT-cryo)

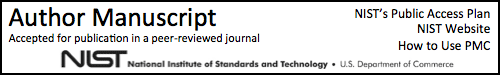

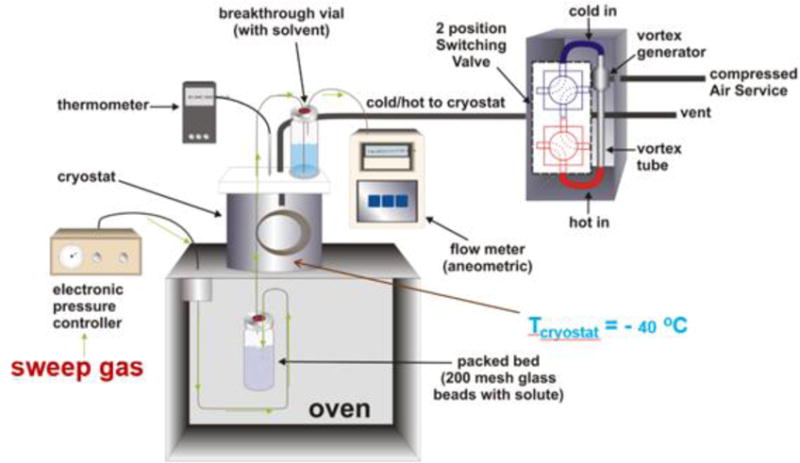

PLOT-cryo is an ultra-sensitive, quantitative, trace dynamic headspace (HS) analysis technique that was used to determine the mass of sample collected from the vapor phase at a given HS collection temperature. This method is used for trace vapor analysis (of polar and non-polar solutes of moderate to low volatility) with high reproducibility and thermodynamic consistency. In PLOT-cryo, a sweep gas is carried through a fused silica tube into a sealed vial containing the sample, with the entire assembly located in an oven (Figure 1). The HS vapors are then carried by the sweep gas and trapped on a PLOT capillary (Figure 2) contained in a temperature-controlled cryostat. PLOT-cryo has the inherent ability to stabilize labile solutes because collection is done at reduced temperature. The PLOT capillary column is robust, reusable, inexpensive and has a large temperature operability for less volatile solutes. While alumina is used in this research, the sorbent phase can be tailored for the chemistry of interest. Analytes are eluted from the PLOT capillary using a suitable solvent or thermal desorption and a gas flow. The collected analytes are then determined by use of any instrumental technique, but typically gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

Figure 1.

A schematic of the experimental apparatus used for ultra-sensitive, quantitative, trace dynamic headspace analysis with an adaptation of PLOT-cryoadsorption. Arrows indicate the flow of the sweep gas. The temperature of the cryostat can reach temperatures as low as −40 °C.

Figure 2.

A schematic of the porous layer open tubular (PLOT) capillary used as a cryoadsorber trap. The PLOT capillary is coated with alumina, is approximately 1 meter long, can be as short as 0.1 meter, and is typically coiled at an 8 cm diameter to allow the capillary to be housed in the cryostat chamber (see Figure 1).

Since the invention of PLOT-cryo, it has been applied to sampling spoiled poultry, gravesoil, pyrolysis products, explosives, and characterizing natural gas and fire debris [23–28]. For the gravesoil experiment, the method was modified to sample the HS air above gravesoil with a motorized pipetter and a PLOT capillary at ambient temperatures. This modified approach provided us with the first generation of an in-the-field trace vapor collection device. Since the gravesoil work, a much more capable in-the-field trace vapor collection device has been built, which utilizes the air compressor from a typical fire truck to provide the suction and temperature control [29, 30]. No other energy inputs are necessary.

PLOT-cryo is an ideal technique for the determination of vapor pressures of cannabinoids. These compounds have very low vapor pressures and are unstable (reactive with oxygen). PLOT-cryo has the advantages of short sampling durations to minimize sample degradation allowing for highly accurate thermophysical properties data measurements on unstable (reactive) compounds. Additionally, PLOT-cryo has the inherent ability to stabilize labile solutes because collection is done at reduced temperature. Providing law enforcement with vapor pressure measurements on the main two important cannabinoids, Δ9-THC and CBD, will help to develop correlations between cannabinoid concentration detected in the breath and cannabinoid concentrations in the blood. Ultimately, these data will help make a breathalyzer for determining driving und the influence of cannabis.

2. Experimental

2.1 Materials

The solvents used in this work were acetonitrile and methanol. They were obtained from a commercial supplier. GC analyses (30 m capillary column of 5 %-phenyl-95 %-dimethyl polysiloxane having a thickness of 0.25 μm, temperature program from 50 °C to 170 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C per minute) with flame ionization (FID) and MS detection revealed the purity to be greater than 99 %. These solvents were used without further purification [31, 32]. CBD and Δ9-THC were also purchased from a commercial supplier. Δ9-THC was reported by the supplier to have a purity of ≥ 98 % and it was provided as a solution in acetonitrile. The CBD was reported to have a purity of ≥ 99 % and it was provided as a crystalline solid. These reported purities were confirmed with GC-MS analyses before experimentation. Δ9-THC was already in solution and thus was used as received, and CBD solutions were prepared with methanol. Purity checks were made on a 30 m capillary column of 5 %-phenyl-95 %-dimethyl polysiloxane having a thickness of 0.25 μm. The inlet temperature was 250 °C with an inlet pressure of 82.73 kPa (12 psi). The initial oven temperature was 150 °C with a 40 °C / min ramp rate to 260 °C, and then a 20 °C / min ramp rate to 300 °C. The oven temperature was held at 300 °C for 2.0 minutes to check for any larger molecular weight impurities. For CBD, the final oven temperature was 325 °C for 2.5 minutes. Chemical data on the cannabinoids and structures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data on the cannabinoids studied in this work. In this table INChI is the International Chemical Identifier, and RMM is the relative molecular mass [33, 34].

| cannabidiol: |

|

| CAS Registry No. 13956-29-1 |

| InChI=1S/C21H30O2/c1-5-6-7-8-16-12-19(22)21(20(23)13-16)18-11-15(4)9-10-17(18)14(2)3/h9,12-13,17-18,22-23H,2,5-8,10-11H2,1,3-4H3/t17-,18+/m0/s1 |

| SMILES=Oc1c(c(O)cc(c1)CCCCC)[C@@H]2\C=C(/CC[C@H]2\C(=C)C)C |

| RMM = 314.463 |

| State = a crystalline solid |

| UV/Vis = λmax: 209 / 275 nm |

| Synonyms: (3R, 4R)-2-p-Menta-1,8-dien-3-yl-5-pentylresorcinol, 2-[1R-3-methyl-6R-(1-methylethenyl)-2-cyclohexen-1-yl]-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol, 2-[(1R,6R)-6-isopropenyl-3-metylcyclohex-2-en-1-yl]-5-pentylbenzene-1,3-diol (IUPAC), CBD, epidolex, trans-(−)-2-p-menta-1,8-dien-3-yl-5-pentylresorcinol |

| Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol: |

|

| CAS Registry No. 1972-08-3 |

| INChI = 1S/C21H30O2/c1-5-6-7-8-15-12-18(22)20-16-11-14(2)9-10-17(16)21(3,4)23-19(20)13-15/h11-13,16-17,22H,5-10H2,1-4H3/t16-,17-/m1/s1 |

| SMILES=CCCCCc1cc(c2c(c1)OC([C@H]3[C@H]2C=C(CC3)C)(C)C)O |

| RMM = 314.469 |

| Synonyms: (−)-(6aR,10aR)-6,6,9-Trimethyl-3-pentyl-6a,7,8,10a-tetrahydro-6H-benzo[c]chromen-1-ol, Δ9-THC, dronabinol, marinol, NSC 134454 |

2.2 PLOT-cryo apparatus and technique

The experimental apparatus developed previously, along with the associated PLOT capillary, are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively [22]. There are seven basic steps to conduct a PLOT-cryo measurement.

the sample compound of interest is placed in a crimp-sealed autosampler vial and heated.

the PLOT capillary is chilled in a separate compartment.

the PLOT capillary is connected to the vial containing the sample and the vial is connected to a gas flow line.

gas is used to sweep the vapors generated by the compound of interest onto a PLOT capillary.

after HS sampling is completed, the PLOT capillary is removed from the PLOT-cryo apparatus.

collected analytes are removed from the PLOT capillary by solvent elution.

collected analytes and solvent are analyzed with an appropriate analytical technique such as GC-MS.

More specifically, to conduct a measurement, a 2 mL crimp-sealed autosampler vial with a small amount of cannabinoid deposited on 2 mm glass beads was placed in a temperature-controlled chamber (the oven in Figure 1). An uncoated capillary was pierced through the autosampler vial septum to direct a flow of the sweep gas into the vial. The tip of the capillary column was placed just above the level of the glass beads. Helium (He) was selected for the sweep gas because solutes diffuse readily through the He gas. Moreover, He has a high thermal conductivity, which is helpful in achieving thermal equilibrium. An activated alumina-coated PLOT capillary (see Figure 2) was pierced through the septum to allow the sweep gas and the constituents in the HS to flow out of the vial and pass through the PLOT capillary.

To increase the collection efficiency, most of the length of each PLOT capillary is housed in a cryostat (a low-temperature chamber) that was cooled with a vortex tube (see Figure 1) [35]. The vortex tube can be adjusted to cool to temperatures as low as -40 °C. In this work, temperatures from 0 °C to -5 °C were used. For the first few experiments with new compounds/samples, sample breakthrough from the PLOT capillary is always checked by allowing the sweep gas exiting the PLOT capillary to bubble through a vial filled with solvent and a small amount of n-tetradecane to serve as a “keeper” solvent. This solution is then analyzed by GC-MS or GC-FID for solute carry-over. Carry-over was not observed for these compounds. Carry-over is rarely observed, however, if carry-over is found than experimental changes can be made to ensure all the compound of interest is trapped on the PLOT capillary. Elimination of carry-over is necessary for quantitative measurements. A few of the experimental parameters that would need to be investigated to develop a method for a compound that exhibited carry-over include the chemistry of the PLOT capillary stationary phase, the length of the PLOT capillary, and the sample collection period.

The flow rate of the He carrier gas at the exit end of the PLOT capillary was monitored periodically over the duration of a collection period with a digital flow meter having an uncertainty of 5 %. An average flow rate was calculated for each HS sampling period. Flow rates ranged from 0.5 to 3.0 mL/min [22]. Headspace collection periods varied depending on the collection temperature. Lower sample temperatures required longer collection periods. The collection temperatures used herein were 60 °C, 80 °C, 100 °C, 120 °C, and 140 °C.

After HS collection, analytes were removed from the PLOT capillary by solvent desorption with acetonitrile for Δ9-THC and methanol for CBD. Solutions of solvent and analytes eluted from the PLOT capillary were subsequently analyzed with GC-MS on a non-polar column (30 m capillary of 5 % phenyl-95 %-dimethyl polysiloxane having a thickness of 0.25 μm). The GC-MS temperature programs were optimized for each cannabinoid and were the same as reported above for determining the starting material purity upon acquisition from the commercial source.

The GC-MS was operated in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode. This process requires external standardization with the pure compounds [32, 36]. Four concentrations of each pure compound were prepared by diluting the external standard in either acetonitrile or methanol; each sample and standard solution was subjected to three replicate analyses to quantify the recovered analyte masses. The recovered masses were corrected for solvent used to desorb analytes from the PLOT capillary and the amount of sweep gas used during the HS collection. Blanks were run frequently by flushing the PLOT capillary with solvent and analyzing the resulting solution.

The sources of uncertainty in evaluating the recovered mass of trace components from the HS are uncertainty in the area quantitation, in the mass calibration, in the temperature measurement, and in the measurement of the total volume of sweep gas. Additionally, there is uncertainty due to the sample impurity and in assuming the ideal gas law. The standard uncertainty, associated with the recovered mass and subsequent vapor pressure calculations for Δ9-THC and CBD with PLOT-cryo was determined to be 13.5 % at the extremely low concentrations (vapor pressures) encountered in this work.

3. Results

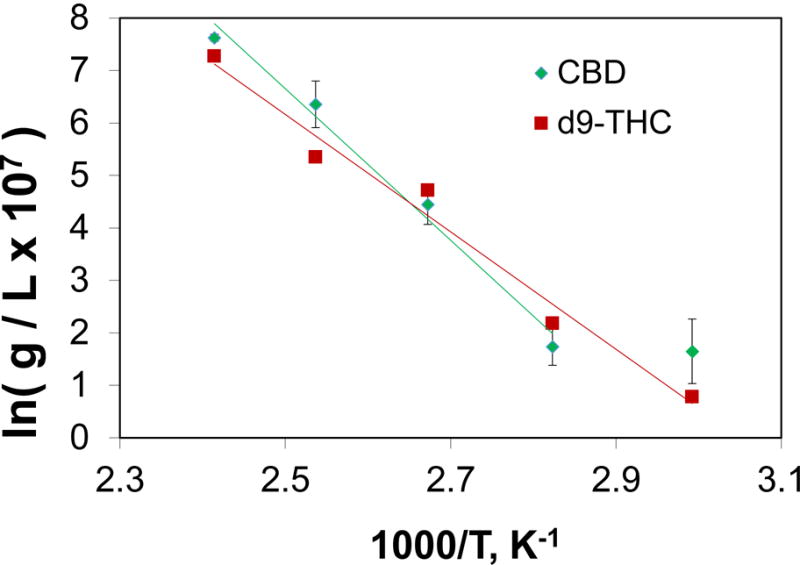

The data in Figures 3 and 4 are presented in the form of Clausius-Clapeyron (or van’t Hoff) equation plots. When a linear relationship of the mass collected (normalized by the volume of sweep gas used to collect the mass) as a function of inverse collection temperature is observed it may be considered confirmation of the thermodynamic consistency and predictive capabilities of the methodology employed here.

Figure 3.

Mass collected of Δ9-THC (squares) and CBD (diamonds) from the HS measurements as a function of collection temperatures. The data are presented in the form of a Clausius-Clapeyron equation plot.

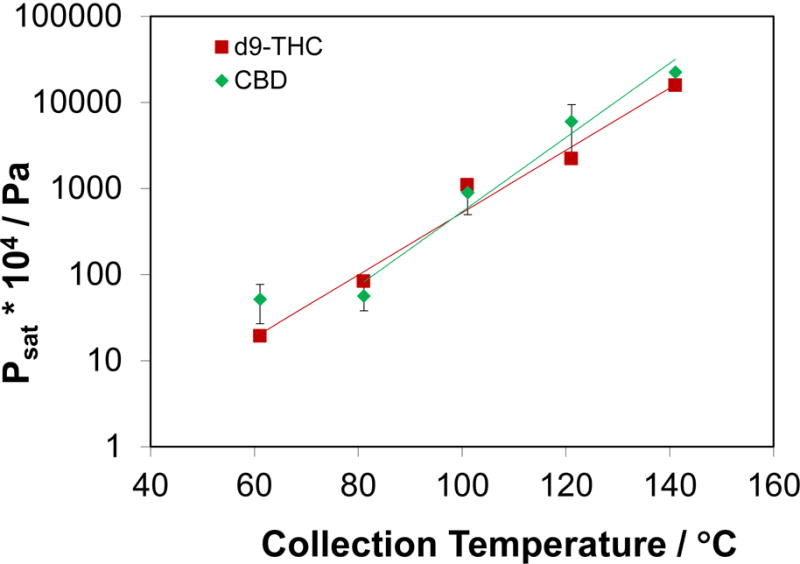

Figure 4.

Vapor pressures of Δ9-THC (squares) and CBD (diamonds) calculated from the HS measurements as a function of collection temperatures.

Of note in Figure 3 is the extremely small amounts of collected analyte in the vapor phase. The data were multiplied by 107 to get values that are positive on a natural log axis. Each data point represents the average of 3–10 repeat measurements at each collection temperature. The uncertainty bars for the Δ9-THC measurements are very small and are almost completely obscured by the symbol size selected for data presentation. Interestingly, the uncertainty of measurements for CBD is much higher. This result is attributed to the decomposition of CBD that was observed by GC-MS (even for the short HS collection times afforded by PLOT-cryo).

Figure 3 also shows that at 60 °C and 80 °C (the last two data points) an equivalent mass of CBD is collected (within the standard deviation). The melting point of CBD is reported to be 67.5 °C ± 0.3 [37]. No melting point data for THC was available in the literature. To estimate the melting point for Δ9-THC, the group contribution method developed by Constantinou was used because it was the prediction method that was most accurate for predicting CBD’s melting point [38]. The predicted melting points were 88.54 °C for CBD and 64.01 °C for Δ9-THC. From these predictions and the experimental data, it is highly likely that CBD is not completely in a melted form until the 80 °C HS collection temperature and it is possible that Δ9-THC is liquid for the entire temperature range investigated. Thus, linear fits to the data exclude the 60 °C measurement for CBD.

Vapor pressure is a pure component property, thus, when PLOT-cryo measurements are made on pure components, these data are readily converted to vapor pressure. The most facile way to convert mass collected to vapor pressure is by use of an EOS, for example, the ideal gas law, equation 1:

| (1) |

where psat is the calculated vapor pressure, m is the recovered mass of vapor (which is determined by calibrated GC-MS), R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 L·kPa·K−1·mol−1), T is the temperature of the oven during HS collection, V is the total volume of sweep gas that flowed through the PLOT capillary, and M is the molar mass of the compound being measured. Figure 4 presents the calculated vapor pressure data for both Δ9-THC and CBD for a range of HS collection temperatures. Figure 4 shows that the vapor pressures for both Δ9-THC and CBD increase with increasing HS collection temperatures.

4. Discussion

On Figures 3 and 4 a linear fit to the data is presented to afford both predictive capability and insight into the important equilibrium processes that dictate mass transfer of these cannabinoids from the liquid phase into the vapor phase. The equilibrium processes that govern this transfer are a combination of the enthalpies of solution and vaporization. To calculate the equilibrium enthalpy of transition (most likely dominated by vaporization), the slopes of the lines presented in Figure 3 are multiplied by the ideal gas constant, R. For Δ 9-THC the enthalpy of transition value is 9.30 × 104 J/mol, and for CBD this value is 1.20 × 105 J/mol. The uncertainties in the slope calculation are 8.1 % for Δ9-THC and 7.1 % for CBD. It is important to note that the enthalpy is often exhibits a temperature dependence itself.

The data presented in Figures 3 and 4 were used to predict the recovered mass of each cannabinoid that would be expected to be collected at room temperature or other interesting temperatures (for example, body temperature, 37 °C). Table 2 presents the experimental values of psat (shown in Figure 4) for Δ9-THC and CBD for 60 °C, 80 °C, 100 °C, 120 °C, and 140 °C. Table 2 also shows the predicted values of p for Δ9 sat -THC and CBD for the experimental temperatures and 25 °C, 30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C. These predictions were corrected to account for the heat capacity due to the phase transition from liquid to solid at the lower temperatures. To place these data in context, previously measured [39] values on n-eicosane by use of concatenated gas saturation techniques are also presented at 30 °C, 40 °C, and 50 °C. This table shows that the vapor pressures for Δ9-THC and CBD at near ambient conditions (25 °C) are approximately 2 orders of magnitude lower than what was measured at 60 °C. Additionally, the vapor pressures measured for these two cannabinoids are approximately 2 orders of magnitude lower than what were measured for n-eicosane, a stable compound with a well-known low vapor pressure.[39]

Table 2.

The experimental values of psat for Δ9-THC and CBD, the predicted values of psat for Δ9-THC and CBD, and the previously measured [39] values on n-eicosane by use of concatenated gas saturation techniques are presented. The experimental uncertainty is 13.5% (1σ) and is discussed in section 2.2. The uncertainties in the slope calculation are 8.1 % for Δ9-THC and 7.1 % for CBD.

| measured Δ 9-THC | measured CBD | predicted Δ 9-THC | predicted CBD | measured n-eicosane | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp / °C | Psat / Pa | Psat / Pa | Psat / Pa | Psat / Pa | Psat / Pa |

| 25 | 2.57E-05 | 2.73E-06 | |||

| 30 | 4.87E-05 | 6.16E-06 | 2.18E-03 | ||

| 40 | 1.15E-04 | 2.90E-05 | 1.29E-02 | ||

| 50 | 5.15E-04 | 1.24E-04 | 4.30E-02 | ||

| 61.1 | 1.93E-03 | 5.18E-03 | 1.69E-03 | 5.60E-04 | 1.30E-01 |

| 81.1 | 8.35E-03 | 5.65E-03 | 1.19E-02 | 6.71E-03 | |

| 101.1 | 1.10E-01 | 8.95E-02 | 6.82E-02 | 6.16E-02 | |

| 121.1 | 2.20E-01 | 6.00E-01 | 3.27E-01 | 4.51E-01 | |

| 141.1 | 1.58E+00 | 2.24E+00 | 1.35E+00 | 2.73E+00 |

The difference in vapor pressures observed for the cannabinoids and n-eicosane can partially be explained by the differences in the molecular structure of these molecules. While n-eicosane is made up of only carbon and hydrogen, the cannabinoids have carbon, hydrogen, and two oxygens in their chemical structure. The oxygen atoms increase the polarity of the compounds, which can affect the thermophysical properties dramatically. Whether polarity alone can account for this interesting result will require additional investigation of the intermolecular interactions of these cannabinoids.

The data were also compared with the predictions using the ThermoDataEngine (TDE) software available from the Thermodynamic Research Center (TRC) at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [40]. Properties were predicted based on group contributions using the Joback, Ambrose-Walton and Wilson-Jasperson methods, correlated by use of the Wagner 25 equation. An uncertainty of 10 percent was chosen (based on decades of TRC experience in the correlation of thermophysical property data) to compare the predictions with the measurements. The measurements made herein fit the TDE predictions within the assumed uncertainty, another indication of their thermochemical consistency.

These vapor pressure measurements were also used to predict a NBT for each cannabinoid. The prediction of the NBT for Δ 9-THC and CBD by three methods are presented in Table 3. Table 3 presents the NBT predicted by the PLOT-cryo experimental data (the predicted data were corrected for changes in heat capacity with the TDE software) and both the Nannoolal and the Joback group contribution methods [41–43]. There are huge discrepancies between the Nannoolal and the Joback group contribution methods used to predict the NBT herein of over 170 °C. It is this kind of discrepancy among these predicted values that shows the importance of having reliable experimental data with which to validate predicted properties. The prediction method used herein clearly agrees more closely with the Nannoolal prediction method. The critical temperature, critical pressure, and critical volume, were all calculated using the NBT predicted with the PLOT-cryo experimental data and are also presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

| Property | Prediction Method | Δ9-THC | CBD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Boiling Point | herein | 690.4 K | 695.1 K |

| Normal Boiling Point | Nannoolal method | 674.5 K | 692.5 K |

| Normal Boiling Point | Joback method | 845.8 K | 888.4 K |

| Critical Temperature | Joback method using NBT predicted herein | 882.4 K | 876.1 K |

| Critical Pressure | Joback method using NBT predicted herein | 1.66×106 Pa | 1.77×106 Pa |

| Critical Volume | Joback method using NBT predicted herein | 939.5 cm3 | 935.5 c m3 |

5. Conclusion

The vapor pressures of two important cannabinoids, CBD and Δ9-THC were measured. These measurements were only possible because of the use of an ultra-sensitive, quantitative, trace dynamic HS analysis technique called porous layered open tubular-cryoadsorption (PLOT-cryo). The vapor pressures measured herein are approximately 2 orders of magnitude lower than those measured for n-eicosane. Differences in the polarity of these molecules can explain part of the observed differences, but further investigated to understand the intermolecular interactions that are impacting the vapor pressures so dramatically are necessary. Additionally, the predicted vapor pressures that would be expected at near ambient conditions (25 °C) were determined to be 2.57×10−5 Pa for Δ9-THC and 3.20×10−5 Pa for CBD. Predictions for the critical temperature, critical pressure and critical volume are also presented. These values are required for rudimentary equation of state development, providing a means for predicting thermophysical properties needed to optimize and design in-the-field breathalyzers for cannabis abuse. Such a device would enable law enforcement personnel to detect driving under the influence of drugs and allow industries to better enforce workplace safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Programs Office (SPO) for its support of this research.

Abbreviations

- 1CBD

cannabidiol

- Δ9-THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- EOS

equation of state

- PLOT-cryo

porous layered open tubular cryoadsorption

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- NBT

normal boiling temperature

- FID

flame ionization detection

- INChI

International Chemical Identifier

- HS

headspace

- TDE

ThermoDataEngine

- TRC

Thermodynamic Research Center

- SIM

selected ion monitoring

- NIST

National Institute of Standards and Technology

References

- 1.Hall W, Lynskey M. Evaluating the public health impacts of legalizing recreational cannabis use in the United States. Addiction. 2016;111(10):1764–73. doi: 10.1111/add.13428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall W, Weier M. Assessing the public health impacts of legalizing recreational cannabis use in the USA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(6):607–15. doi: 10.1002/cpt.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masten SV, Guenzburger GV. Changes in driver cannabinoid prevalence in 12 U.S. states after implementing medical marijuana laws. J Safety Res. 2014;50:35–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huestis MA. Cannabis-impaired driving: a public health and safety concern. Clin Chem. 2015;61(10):1223–5. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.245001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman RL, Huestis MA. Cannabis effects on driving skills. Clin Chem. 2013;59(3):478–92. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.194381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetz G, Spurgin A, Pierce RS, Gorelick DA, Gaffney G, Huestis MA. Cannabis effects on driving longitudinal control with and without alcohol. J Appl Toxicol. 2016;36(11):1418–29. doi: 10.1002/jat.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemos NP, San Nicolas AC, Volk JA, Ingle EA, Williams CM. Driving Under the Influence of Marijuana Versus Driving and Dying Under the Influence of Marijuana: A Comparison of Blood Concentrations of Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol, 11-Hydroxy-Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol, 11-Nor-9-Carboxy-Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Other Cannabinoids in Arrested Drivers Versus Deceased Drivers. J Anal Toxicol. 2015;39(8):588–601. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkv095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariotti Kde C, Marcelo MC, Ortiz RS, Borille BT, Dos Reis M, Fett MS, Ferrao MF, Limberger RP. Seized cannabis seeds cultivated in greenhouse: A chemical study by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and chemometric analysis. Sci Justice. 2016;56(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Backer B, Maebe K, Verstraete AG, Charlier C. Evolution of the content of THC and other major cannabinoids in drug-type cannabis cuttings and seedlings during growth of plants. J Forensic Sci. 2012;57(4):918–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Happyana N, Agnolet S, Muntendam R, Van Dam A, Schneider B, Kayser O. Analysis of cannabinoids in laser-microdissected trichomes of medicinal Cannabis sativa using LCMS and cryogenic NMR. Phytochemistry. 2013;87:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanuš LO. Cannabidiol – Recent Advances. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2007;4(8):1678–1692. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swortwood MJ, Newmeyer MN, Andersson M, Abulseoud OA, Scheidweiler KB, Huestis MA. Cannabinoid disposition in oral fluid after controlled smoked, vaporized, and oral cannabis administration. Drug Test Anal. 2016 doi: 10.1002/dta.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetz G, Spurgin A, Gorelick DA, Gaffney GR, Huestis MA. Effect of Blood Collection Time on Measured Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Concentrations: Implications for Driving Interpretation and Drug Policy. Clin Chem. 2016;62(2):367–77. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.248492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anizan S, Milman G, Desrosiers N, Barnes AJ, Gorelick DA, Huestis MA. Oral fluid cannabinoid concentrations following controlled smoked cannabis in chronic frequent and occasional smokers. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405(26):8451–61. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsot A, Audebert C, Attolini L, Lacarelle B, Micallef J, Blin O. Comparison of Cannabinoid Concentrations in Plasma, Oral Fluid and Urine in Occasional Cannabis Smokers After Smoking Cannabis Cigarette. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;19(3):411–422. doi: 10.18433/J3F31D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson M, Scheidweiler KB, Sempio C, Barnes AJ, Huestis MA. Simultaneous quantification of 11 cannabinoids and metabolites in human urine by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry using WAX-S tips. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(23):6461–71. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9765-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Himes SK, Scheidweiler KB, Beck O, Gorelick DA, Desrosiers NA, Huestis MA. Cannabinoids in exhaled breath following controlled administration of smoked cannabis. Clin Chem. 2013;59(12):1780–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.207407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee D, Bergamaschi MM, Milman G, Barnes AJ, Queiroz RH, Vandrey R, Huestis MA. Plasma Cannabinoid Pharmacokinetics After Controlled Smoking and Ad libitum Cannabis Smoking in Chronic Frequent Users. J Anal Toxicol. 2015;39(8):580–7. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkv082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee D, Vandrey R, Mendu DR, Anizan S, Milman G, Murray JA, Barnes AJ, Huestis MA. Oral fluid cannabinoids in chronic cannabis smokers during oral delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol therapy and smoked cannabis challenge. Clin Chem. 2013;59(12):1770–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.207316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Racamonde I, Villaverde-de-Saa E, Rodil R, Quintana JB, Cela R. Determination of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-nor-9-carboxy-Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in water samples by solid-phase microextraction with on-fiber derivatization and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1245:167–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilsey BL, Deutsch R, Samara E, Marcotte TD, Barnes AJ, Huestis MA, Le D. A preliminary evaluation of the relationship of cannabinoid blood concentrations with the analgesic response to vaporized cannabis. J Pain Res. 2016;9:587–98. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S113138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno TJ. Simple Quantitative Headspace Analysis by Cryoadsorption on a Short Alumina PLOT Column. Journal of Chromatographic Science. 2009;47(8):569–574. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/47.7.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovestead TM, Bruno TJ. Trace Headspace Sampling for Quantitative Analysis of Explosives with Cryoadsorption on Short Alumina PLOT Columns. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82(13):5621–5627. doi: 10.1021/ac1005926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovestead TM, Bruno TJ. Detection of poultry spoilage markers from headspace analysis with cryoadsorption on short alumina PLOT columns. Food Chemistry. 2010;121(4):1274–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovestead TM, Bruno TJ. Detecting gravesoil with cryoadsorption on short alumina PLOT columns. Forensic Sci Int. 2011;204:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burger JL, Lovestead TM, Bruno TJ. Composition of the C6+ Fraction of Natural Gas by Multiple Porous Layer Open Tubular Capillaries Maintained at Low Temperatures. Energy & Fuels. 2016;30(3):2119–2126. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichols JE, Harries ME, Lovestead TM, Bruno TJ. Analysis of arson fire debris by low temperature dynamic headspace adsorption porous layer open tubular columns. Journal of Chromatography A. 2014;1334:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruno TJ, Nichols JE. Method and apparatus for pyrolysis–porous layer open tubular column--cryoadsorption headspace sampling and analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1286:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruno TJ. Field portable low temperature porous layer open tubular cryoadsorption headspace sampling and analysis part I: Instrumentation. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1429:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harries M, Bukovsky-Reyes S, Bruno TJ. Field portable low temperature porous layer open tubular cryoadsorption headspace sampling and analysis part II: Applications. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1429:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruno TJ, Svoronos PDN. CRC Handbook of Fundamental Spectroscopic Correlation Charts, Taylor and Francis CRC Press. Boca Raton, FL. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruno TJ, Svoronos PDN. CRC Handbook of Basic Tables for Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed., CRC Taylor and Francis. Boca Raton. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Product information, Cayman Cchemical. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linstrom PJ, Mallard WG, NIST Chemistry WebBook . NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology. Gaithersburg MD: Jun, 2011. 20899 ( http://webbook.nist.gov) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruno TJ. Vortex cooling for subambient temperature gas chromatography. Analytical Chemistry. 1986;58(7):1595–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.NIST/EPA/NIH Mss Spectral Database, Standard Reference Database 1, 2005. SRD Program, National Institute of Standards and Technology; Gaithersburg, MD: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stinchcomb AL, Valiveti S, Hammell DC, Ramsey DR. Human skin permeation of Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and cannabinol. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2004;56(3):291–297. doi: 10.1211/0022357022791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constantinou L, Gani R. New Group Contribution Method for Estimating Properties of Pure Compounds. AIChE J. 1994;40(10):1697. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widegren JA, Bruno TJ. Vapor Pressure Measurements on Low-Volatility Terpenoid Compounds by the Concatenated Gas Saturation Method. Environmental Science & Technology. 44(1):388–393. doi: 10.1021/es9026216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diky V, Chirico RD, Frenkel M, Bazyleva A, Magee JW, Paulechka E, Kazakov A, Lemmon EW, Muzny CD, Smolyanitsky AY, Townsend SA, Kroenlein K. ThermoData Engine (TDE) Version 10.1 - Pure Compounds, Binary Mixtures, Ternary Mixtures, and Chemical Reactions, NIST Standard Reference Database 103b. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Standard Reference Data Program; Gaithersburg, MD: 2016. http://nist.gov/srd/nist103b.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nannoolal Y, Rarey J, Remjugernath D, Cordes W. Estimation of pure component properties Part 1. Estimation of the normal boiling point of non-electrolyte organic compounds via group contributions and group interactions. Fluid Phase Equilibria. 2004;226:45–63. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joback KG. M.S. Thesis in Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cambridge, MA: Jun, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid RC, Prausnitz JM, Poling BE. The Properties of Gases & Liquids. 4th. McGraw-Hill Book Company; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]