Abstract

Background

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are an important cause of death and disability in Africa. This study estimates the monetary value of human lives lost due to NTDs in the continent in 2015.

Methods

The lost output or human capital approach was used to evaluate the years of life lost due to premature deaths from NTDs among 10 high/upper-middle-income (Group 1), 17 middle-income (Group 2) and 27 low-income (Group 3) countries in Africa. The future losses were discounted to their present values at a 3% discount rate. The model was re-analysed using 5% and 10% discount rates to assess the impact on the estimated total value of human lives lost.

Results

The estimated value of 67 860 human lives lost in 2015 due to NTDs was Int$ 5 112 472 607. Out of that, 14.6% was borne by Group 1, 57.7% by Group 2 and 27.7% by Group 3 countries. The mean value of human life lost per NTD death was Int$ 231 278, Int$ 109 771 and Int$ 37 489 for Group 1, Group 2 and Group 3 countries, respectively. The estimated value of human lives lost in 2015 due to NTDs was equivalent to 0.1% of the cumulative gross domestic product of the 53 continental African countries.

Conclusions

Even though NTDs are not a major cause of death, they impact negatively on the productivity of those affected throughout their life-course. Thus, the case for investing in NTDs control should also be influenced by the value of NTD morbidity, availability of effective donated medicines, human rights arguments, and need to achieve the NTD-related target 3.3 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 (on health) by 2030.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40249-017-0379-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Neglected tropical diseases, Non-health gross domestic product loss, Value of life, Lost output approach, Human capital approach, Africa

Multilingual abstracts

Please see Additional file 1 for translations of the abstract into the five official working languages of the United Nations.

Background

Africa has 54 countries: 1 (1.9%) high-income, 9 (16.7%) upper-middle-income, 17 (31.5%) lower-middle-income and 27 (50%) low-income countries (see Table 1) [1]. The continent had a population of approximately 1 184 500 000 people in 2015 [2]. The total gross domestic product (GDP) for Africa that year was approximately International Dollars (Int$) 6 045 831 000 000 in 2015 [3].

Table 1.

World Bank analytical classifications

| Economic classification | Gross national income per capita in US$ (the World Bank’s fiscal year – 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016) | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| High-income economies | > 12 475 | Seychelles (1) |

| Upper-middle-income economies | 4 036–12 475 | Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Libya, Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa (9) |

| Lower-middle-income economies | 1 026–4 035 | Cape Verde, Cameroon, Republic of Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Sudan, Swaziland, Tunisia, Zambia (17) |

| Low-income economies | ≤ 1 025 | Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zimbabwe (27) |

Source: World Bank [1]

Globally, an estimated total of 56 228 951 deaths from all causes occurred in 2015. Approximately 10 522 529 of those deaths happened in the African continent. Of these, 5 497 996 (52.2%) were from communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions; 3 985 251 (37.9%) were from non-communicable diseases; and 1 039 282 (9.9%) were from injuries [4].

Out of the total global number of deaths, 206 155 resulted from NTDs, of which 67 860 (32.9%) occurred in Africa [4].

According to various reports [5–13], NTDs afflict mainly the poorest people in Africa, often with devastating effects for their entire life-course. They erode patients’ intellectual capacities, school attendance and educational performance, labour productivity and income earning potential, and thus aggravate and perpetuate inter-generational poverty among societies living in endemic areas [5–13].

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted resolution A/69/L.85 on the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. It contains 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), of which SDG 3 is centred on ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all. The SDG has 13 targets, of which target 3.3 reads: “By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases” (p. 16) [14]. There is therefore an urgent need for collating economic burden evidence to use in advocacy in African countries among the ministries of finance, the private sector and development partners to increase investment towards global efforts to achieve the abovementioned target on ending the NTD epidemic.

Globally, a number of studies have been conducted on the economic burden of a single NTD [15–31] in one or a few countries [32, 33]. To date, no study has attempted to measure the value of human lives lost due to NTDs in all or the majority of countries in continental Africa. Therefore, the study reported in this paper was an attempt to contribute to bridging this knowledge gap.

The paper answers the question: What is the value of human lives lost due to NTDs in continental Africa? More specifically, the objective was to estimate the monetary value of human lives lost due to NTDs in Africa in 2015.

Methods

Study area and population

This study was conducted in the African continent, which has a total of 54 countries. Somalia was excluded from the study, as it did not have data on per-capita GDP and per-capita total health expenditure.

The study includes the following 16 NTDs as listed in the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Estimates 2015: African trypanosomiasis, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, cysticercosis, echinococcosis, dengue, rabies, ascariasis, leprosy, Chagas disease, trachoma, onchocerciasis, trichuriasis, hookworm disease and food-borne trematodes. There were no deaths reported in the WHO [4] source for the last six NTDs in African countries.

Study design: The lost output approach or human capital approach (HCA)

The late Professor Gavin Mooney [34] outlined three types of approaches used in deriving monetary values for human life: (a) the implied values (or revealed preferences) approach, which is based on values implied by past healthcare decisions; (b) the HCA or lost output approach, which equates the value of human life with the value of livelihood; and (c) the willingness-to-pay (or contingent valuation) approach, which is based on how much individuals are prepared to pay to reduce the risk of morbidity or death. The strengths and weaknesses of each approach have been exhaustively discussed in Linnerooth [35], Mooney [36] and Jones-Lee [37].

The HCA or lost output approach was first applied by Petty [38]. However, its theoretical and practical underpinnings have been refined and enhanced by Fein [39], Mushkin and Collings [40], Weisbrod [41], and Landefeld and Seskin [42]. The approach has been widely applied in Asia-Pacific countries [43–53], North America [54–60] and Europe [61–66]. It has been applied in Africa to estimate the economic burdens of cholera [67], malaria [68, 69], HIV/AIDS [70, 71] and diabetes mellitus [72]. The specific approach used in the current study is similar to that developed and applied in estimating the indirect costs of child mortality [73], Ebola virus disease [74], tuberculosis [75] and maternal mortality [76] in the African region.

The choice of the HCA or lost output approach to place monetary values on years of human lives lost due to NTDs was based on successful past applications in estimating indirect costs of a number of health conditions in the region [73–76]; and availability of data on GDPs and total health expenditure per capita for all countries (except one) in Africa.

According to Mooney [34], this approach:

“suggests that a life’s value can be measured in terms of the future expected life-time earnings of the individual concerned, adjusted to allow for working life expectancy, participation rates in the labour force, and various other factors. The value of life or, more accurately in this context, of livelihood is then obtained by discounting these future earnings to their present value as is usual in public and private investment decisions. For this reason, economists term it the ‘human capital’ approach.” (p.7)

The GDP is a monetary measure of the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a specific period, e.g. yearly in our case [77, 78]. The NTD premature mortality impacts negatively on all the components of the GDP, including consumption expenditure, investment, government expenditure and net exports, i.e. exports less imports. We used per-capita GDP data to value the years of life lost (YLLs) to premature mortality from NTDs. The per-capita GDP is obtained by dividing the total GDP of a country by its population. The WHO [79] and Chisholm et al. [80] advise that when the focus of an economic burden of a disease study is on overall productivity losses, the quantity of interest should be the effect on the pooled output of remunerated and unremunerated labour as measured by non-health GDP.

The value of human lives lost (VHLLost) due to NTDs in Africa is equal to the sum of non-health GDP losses of the 53 countries. The VHLLostdue to NTD deaths (NTDDs) in a country is the sum of the potential non-health GDP lost due to NTDDs among people aged 0–4 years (VHLLost 0 − 4), 5–14 years (VHLLost 5 − 14), 15–29 years (VHLLost 15 − 29), 30–49 years (VHLLost 30 − 49), 50–59 years VHLLost 50 − 59, 60–69 years (VHLLost 60 − 69), and 70 years and above VHLLost ≥70 [73–76].

The VHLLostassociated with NTDDs among persons of a specific age group equals the total discounted YLLs per-capita non-health GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) and the total NTDDs for the age group [73, 74, 76]. Each country’s discounted value of human lives loss associated with NTDDs was appraised using the eqs. (1) to (8), as shown below:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

Where: 1/(1 + r)k is the discount factor that converts future VHLLostinto today’s dollars; r is an interest rate that measures the opportunity cost of lost livelihood or output; is the summation from year i to k; i is the first year of life lost, and k is the final year of the total number of YLLs per NTDD, which is obtained by subtracting the mean age at death for NTD-related causes from global maximum average life expectancy; NHGDPPC Int$ is per capita non-health GDP in PPP, which is obtained by subtracting per-capita total health expenditure (PCTHE) from per-capita GDP (GDPPC Int$ ); NTDD 0 − 4 is the number of NTDDs among those aged 0–4 years in country m in 2015; NTDD 5 − 14 is the number of NTDDs among those aged 5–14 years in country m in 2015; NTDD 15 − 29 is the number of NTDDs among those aged 15–29 years in country m in 2015; NTDD 30 − 49 is the number of NTDDs among those aged 30–59 years in country m in 2015; NTDD 50 − 59is the number of NTDDs among those aged 50–59 years in country m in 2015;NTDD 60 − 69is the number of NTDDs among those aged 60–69 years in country m in 2015; and NTDD ≥70 is the number of NTDDs among those aged 70 years and above in country m in 2015. The base year to which future losses in value of human life were discounted was 2015. The discount factor used for losses occurring at diverse years hinge on both the number of years, k , over which discounting is done and the discount rate (r) [76, 81–83].

Data sources

The abovementioned eight equations were estimated using data from the WHO, International Labour Organization (ILO) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) sources. The parameters used in the analysis and data sources are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters used in the analysis

| Variable | Indicator | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality in 2015 | Numbers and ratios of NTDDs occurring in the seven age brackets, per country | WHO [4] |

| YLLs | Global maximum YLLs for each of the seven age brackets | WHO [85] |

| Legal minimum age for employment | 15 years | ILO [86] |

| Population in 2015 | Population per country | WHO [2] |

| Average economic output per person in each of the 53 African countries with data in 2015 | GDP per capita per country | IMF [3] |

| Expenditure on health in 2015 | Projected 2015 total expenditure on health (THE) per person per country in Africa (projected using 2013 and 2014 THE data) | WHO [87] |

Data analysis

The analysis was done using Excel software (Microsoft, New York) following a number of steps:

Step 1: The countries were categorised into three economic groups for comparative purposes, as shown in Table 2. Group 1: 10 high- and upper-middle-income countries; Group 2: 17 lower-middle-income countries; and Group 3: 27 low-income countries [1].

Step 2: The eight formulas outlined above were built into a spreadsheet for each of the 53 countries.

Step 3: The NTDDs by country and age brackets were downloaded from the WHO Global Health Estimates 2015 [4] (see Additional file 2). The methodological details of how the number of deaths for each NTD by age bracket per country was calculated are detailed in a WHO source [84].

Step 4: The life expectancy data used for all countries were sourced from Table 2.1 of the WHO document entitled “WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000 – 2015” [85] (see Additional file 3). Thus, following this estimation, instead of using individual African country’s life expectancies, we used the highest global projected life expectancies achieved by women in Japan and the Republic of Korea, with a life expectancy at birth of 91.9 years [85]. According to the WHO, this represents the maximum life span of an individual in good health who is not exposed to avoidable health risks or severe injuries, and receives appropriate health services. The WHO [85] provides maximum life spans for 20 age groups, while our study has seven age groups. The maximum life spans (in years) for the seven age groups under consideration in this study were obtained as follows:

0–4 is the average of the highest global life spans for neonatal (91.93 years), post-neonatal (91.55 years) and 1–4 years (89.41 years), i.e. (91.93 + 91.55 + 89.41)/3 = 90.96 years;

5–14 is the average of the highest global life spans for those aged 5–9 and 10–14 years, i.e. (84.52 + 79.53)/2 = 82.025 years;

15–29 is the average of the highest global life spans for those aged 15–19, 20–24 and 25–29 years, i.e. (74.54 + 69.57 + 64.6)/3 = 69.57 years;

30–49 is the average of the highest global life spans for those aged 30–34, 35–39, 40–44 and 45–49 years, i.e. (59.63 + 54.67 + 49.73 + 44.81)/4 = 52.21 years;

50–59 is the average of the highest global life spans for those aged 50–54 and 55–59 years, i.e. (39.92 + 35.07)/2 = 37.495 years;

60–69 is the average of the highest global life spans for those aged 60–64 and 65–69 years, i.e. (30.25 + 25.49)/2 = 27.87 years;

70+ years is the average of the highest global life spans for those aged 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and 80 + years, i.e. (20.77 + 16.43 + 12.51 + 7.6)/4 = 14.3275 years.

Given that the legal minimum working age is 15 years, as according to the ILO [86], only the years above 14 were considered when calculating the productive YLLs for the 0–4 and 5–14 years’ age brackets.

Step 5: The YLLs obtained in Step 4 were discounted at a discount rate of 3%.

Step 6: The national and per-capita GDP in Int$ (or PPP) were downloaded from the IMF website [3].

Step 7: The non-health per-capita GDP in Int$ or PPP (NHGDPPC) was estimated (see Additional file 4). The NHGDPPC was obtained by subtracting per-capita total health expenditure from per-capita GDP [87].

Step 8: Sensitivity analysis was conducted. This study used a 3% discount rate, which has been used in past economic evaluation and health systems studies [67, 73, 84, 85, 88–90]. In order to gauge the sensitivity of the value of human life estimates to discount rate, eqs. (1) to (8) were re-estimated with 5% and 10% discount rates. Those equations were subsequently re-estimated assuming Africa’s maximum life expectancy of 75.6 years (i.e. life expectancy for Algeria) for all countries instead of their actual life expectancies to determine the impact on the value of human life estimates.

Step 9: Each country’s population and NTDDs were sorted into three economic groups, i.e. Group 1, Group 2 and Group 3 (see Table 3).

Step 10: The value of human life estimates for various countries were grouped into the three groups and descriptive statistics were calculated.

The process of estimating value of human life lost due to NTDDs is illustrated in Additional file 5 using actual data on Egypt.

Table 3.

Total population and NTDDs by economic group in Africa

| Economic class | Population in 2015 | NTDDs in 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| High-income and upper-middle-income countries (Group 1) | 134 117 000 | 3 225 |

| Lower-middle-income countries (Group 2) | 509 004 000 | 26 888 |

| Low-income countries (Group 3) | 541 379 000 | 37 747 |

| TOTAL | 1 184 500 000 | 67 860 |

Source: WHO [2]

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not require approval from the Meru University of Science and Technology Institutional Research Ethics Review Committee because it did not involve the use of any animal, or human data or tissue. In addition, the study did not involve any participation of human beings. It was based completely on secondary statistical data published on the WHO, World Bank and IMF websites.

Results

An estimated 67 860 (1.23%) of communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions deaths resulted from 16 NTDs [4]. About 8.1% of these deaths occurred among those aged 0–4 years, 16.7% among those aged 5–14 years, 21.4% among those aged 15–29 years, 23.8% among those aged 30–49 years, 10.1% among those aged 50–59 years, 10.2% among those aged 60–69 years, and 9.7% among those aged 70 years and above. Thus, 55.3% of NTDDs occurred among the most productive age bracket of 15–59 years.

About 4.75% of the NTDDs were borne by the high- and upper-middle-income countries (Group 1), 39.62% by the lower-middle-income countries (Group 2) and 55.62% by the low-income countries (Group 3). The mean NTDDs per country was 1257 (STD = 2329); varying from a minimum of 1 in Seychelles to a maximum of 13 944 in Nigeria. The non-health GDP per capita in the continent was Int$ 5724 (STD = 7233), ranging from Int$ 739 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to Int$ 37 598 in Equatorial Guinea. The continental mean total expenditure on health in 2015 was Int$ 315 (STD = 325), varying from Int$ 24.7 in Madagascar to Int$ 1200 in South Africa.

Value of human life loss attributable to NTDs

The 67 860 NTDDs led to a loss of human life worth Int$ 5 112 472 607; which is approximately 0.1% of the Continent’s GDP in 2015 (see Table 4). Almost 14.6% of the loss was suffered by Group 1, 57.7% by Group 2 and 27.7% by Group 3 countries. The mean value of human life lost was Int$ 75 339 per NTDD. The expected value of human lives lost across the continent varied widely, from Int$ 185 766 in Sao Tome and Principe to Int$ 1 625 450 009 in Nigeria. The potential value of human lives lost was under Int$ 10 million in 16 countries, between Int$ 10 million and Int$ 50 million in 21 countries, between Int$ 51 million and Int$ 100 million in one country, and over Int$ 100 million in 15 countries.

Table 4.

Present value of human lives lost due to NTDDs in Africa (Int$ or PPP, in 2015)

| Summary of indirect costs | High-income and upper-middle- income countries Sub-total cost (Int$) |

Lower-middle- income countries Sub-total cost (Int$) |

Low-income countries Sub-total cost (Int$) |

Grand total cost (Int$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1). Total present value of NTDDs | 745 815 366 | 2 951 569 697 | 1 415 087 545 | 5 112 472 607 |

| (2). Average present value per NTDD | 231 278 | 109 771 | 37 489 | 75 339 |

| (3). Average present value per person in population | 5.6 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 4.3 |

| % of grand total | 14.6 | 57.7 | 27.7 | 100 |

Out of the total loss in the entire continent, 19.1% was borne by those aged 0–4 years, 21.9% by those aged 5–14 years, 28.4% by those aged 15–29 years, 25.8% by those aged 30–49 years, 4% by those aged 50–59 years, 0.5% by those aged 60–69 years, and 0.2% by those aged 70 years and above. Thus, those in the most productive age bracket of 15–59 years bore 58.2% of the losses.

Value of human life lost among group 1 countries

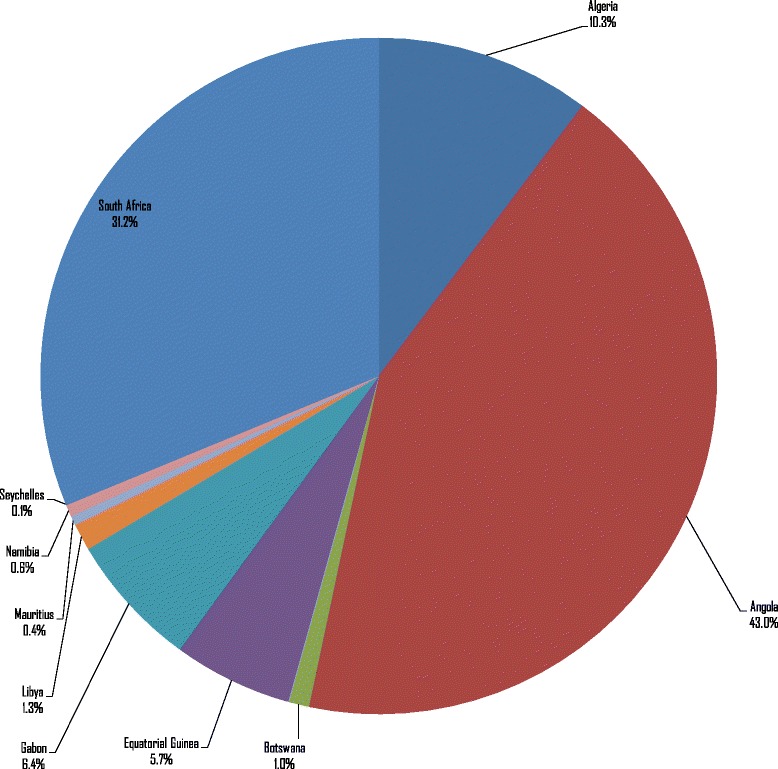

The 3225 NTDDs in Group 1 countries resulted in an expected loss of Int$ 745 815 366 in terms of the value of human life in 2015, which was equal to 0.04% of the group’s total GDP. The total value of human lives lost varied greatly, from Int$ 496 645 in Seychelles to Int$ 321 053 534 in Angola. Figure 1 shows the distribution of Group 1’s total value of human lives lost. Approximately 74.2% of the loss was borne by Angola and South Africa.

Fig. 1.

Value of human lives lost due to NTDDs in high-income and upper-middle-income countries (Group 1) of Africa (Int$, in 2015)

Group 1’s total present value of human life lost was distributed as follows across the NTDs: 42% schistosomiasis, 25.8% cysticercosis, 15.6% rabies, 5.2% ascariasis, 3.7% African trypanosomiasis, 3.3% leprosy, 2.3% leishmaniasis, 1.2% dengue, and 0.9% echinococcosis (see Table 5). Thus, the first three diseases accounted for 83.3% of losses incurred by Group 1.

Table 5.

Distribution of present value of human lives lost in Africa across economic groups and NTDs (in 2015 Int$ or PPP)

| NTDs | Group 1 Deaths in 2015 | Group 1 Present Values in 2015 INT$ | % | Group 2 Deaths in 2015 | Group 2 Present Values in 2015 INT$ | % | Group 3 Deaths in 2015 | Group 3 Present Values in 2015 INT$ | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Trypanosomiasis | 122 | 28 205 045 | 3.8 | 157 | 17 233 681 | 0.6 | 5132 | 192 392 224 | 13.6 |

| Chagas disease | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Schistosomiasis | 1354 | 313 029 760 | 42.0 | 10 798 | 1 185 282 070 | 40.2 | 10 645 | 399 067 659 | 28.2 |

| Leishmaniasis | 74 | 17 107 978 | 2.3 | 2467 | 270 799 302 | 9.2 | 3331 | 124 875 000 | 8.8 |

| Lymphatic filariasis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Onchocerciasis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cysticercosis | 832 | 192 349 158 | 25.8 | 6610 | 725 570 891 | 24.6 | 8907 | 333 912 225 | 23.6 |

| Echinococcosis | 28 | 6 473 289 | 0.9 | 176 | 19 319 285 | 0.7 | 189 | 7 085 372 | 0.5 |

| Dengue | 39 | 9 016 367 | 1.2 | 353 | 38 748 340 | 1.3 | 311 | 11 658 999 | 0.8 |

| Trachoma | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rabies | 504 | 116 519 202 | 15.6 | 4835 | 530 731 507 | 18.0 | 6883 | 258 035 011 | 18.2 |

| Ascariasis | 167 | 38 608 545 | 5.2 | 932 | 102 304 398 | 3.5 | 604 | 22 643 200 | 1.6 |

| Trichuriasis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hookworm disease | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Food-borne trematodes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Leprosy | 106 | 24 506 023 | 3.3 | 561 | 61 580 222 | 2.1 | 1745 | 65 417 855 | 4.6 |

| TOTAL | 3225 | 745 815 366 | 100 | 26 888 | 2 951 569 697 | 100 | 37 747 | 1 415 087 545 | 100 |

Value of human life lost among group 2 countries

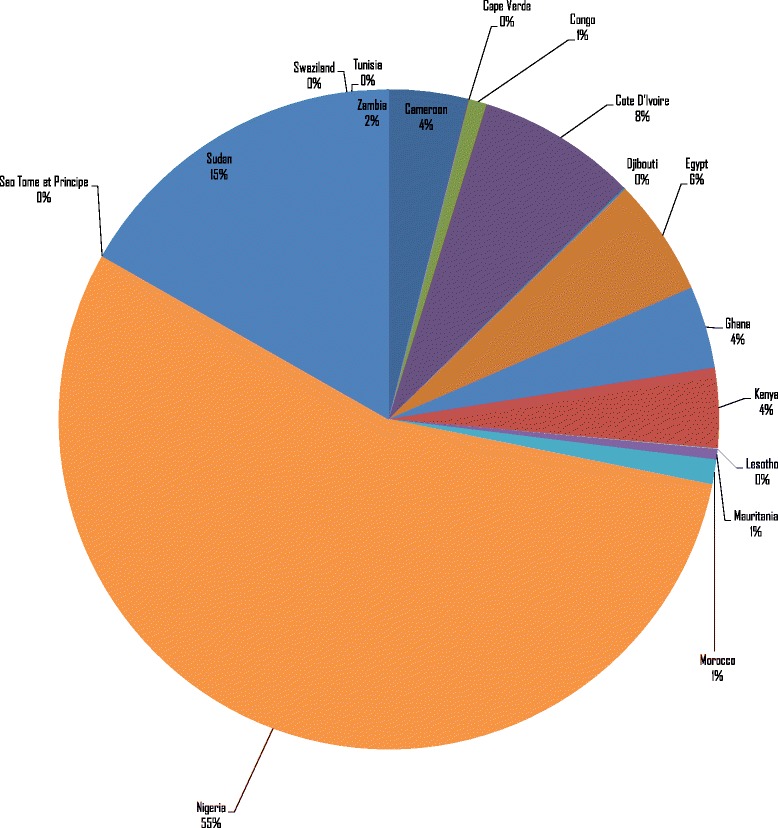

The 26 888 NTDDs in Group 2 countries resulted in an expected total loss of Int$ 2 951 569 697 in the value of human life in 2015, or 0.09% of the group’s total GDP. The loss varied from Int$ 185 766 in Sao Tome and Principe to Int$ 1 625 450 009 in Nigeria. Figure 2 shows the distribution of Group 2’s total value of human lives lost. Approximately 55.1% of Group 2’s expected loss was borne by Nigeria alone. About 83% of Group 2’s expected loss was borne by Cote d’Ivoire, Egypt, Nigeria and Sudan.

Fig. 2.

Value of human lives lost due to NTDDs in lower-middle-income countries (Group 2) of Africa (Int$, in 2015)

Group 2’s total present value of human life lost was distributed as follows across the NTDs: 40.0% schistosomiasis, 24.6% cysticercosis, 18% rabies, 9.2% leishmaniasis, 3.5% ascariasis, 2.1% leprosy, 1.3% dengue, 0.7% echinococcosis, and 0.6% African trypanosomiasis. Therefore, the first three diseases were responsible for 82.6% of the Group 2 losses (see Table 5).

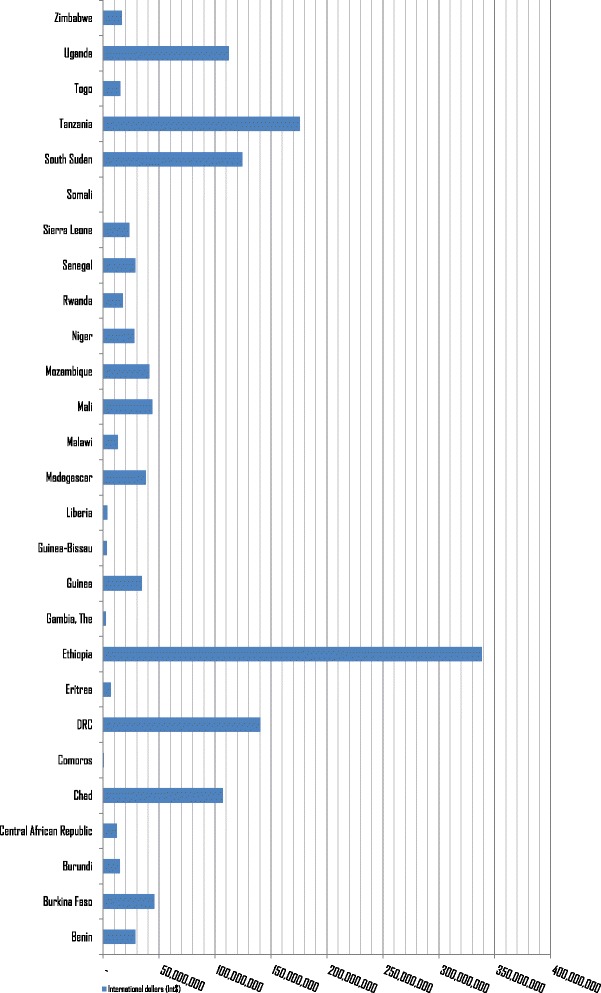

Value of human life lost among group 3 countries

The estimated 37 747 NTDDs that occurred among Group 3 countries led to a total expected loss in value of human life of Int$ 1 415 087 545 in 2015, which is equivalent to 0.2% of the group’s total GDP. The expected loss ranged from Int$ 725 391 in Comoros to Int$ 338 485 350 in Ethiopia, which bore 23.9% of the group’s loss. The distribution of Group 3’s total value of human lives lost is depicted in Fig. 3. The DRC, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda together accounted for 63% of the expected loss in this group. It is interesting to note that although Group 3 had 10 000 more NTDDs than Group 2, the value of human lives lost of Group 2 was higher than that of Group 3 by Int$ 1.54 billion because Group 2 had higher per-capita GDP.

Fig. 3.

Value of human lives lost due to NTDDs in low-income countries (Group 3) of Africa (Int$, in 2015)

Group 3’s total present value of human life lost was distributed as follows across the NTDs: 28.2% schistosomiasis, 23.7% cysticercosis, 18.2% rabies, 13.6% African trypanosomiasis, 8.8% leishmaniasis, 4.6% leprosy, 1.6% ascariasis, 0.8% dengue and 0.5% echinococcosis. Thus, the first three diseases were responsible for 70% of Group 3’s losses (see Table 5).

Average value of human life losses

The mean value of human lives lost per NTDD and per person in the population for the 53 countries are displayed in Table 6. These values were obtained by dividing each group’s total value of human life lost by its total NTDDs. The mean value of human life lost per person in the population for each group was calculated by dividing the group’s total value of human life lost by its population.

Table 6.

Discounted value of human lives lost due to NTDDs among continental Africa countries (Int$ or PPP, in 2015)

| Country | (A) Population | (B) NTDDs | (C) Total value of all human lives lost due to NTDs (Int$) | (D) Value of human life lost per NTDD (Int$) [D = (C/B)] |

(E) Value of human life lost per person in population (Int$) [E = (C/A)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 39 667 000 | 25 | 76 687 914 | 304 735 | 1.9 |

| Angola | 25 022 000 | 1854 | 321 053 534 | 173 188 | 12.83 |

| Benin | 10 880 000 | 599 | 28 473 736 | 47 543 | 2.62 |

| Botswana | 2 262 000 | 22 | 7 430 499 | 341 854 | 3.28 |

| Burkina Faso | 18 106 000 | 1088 | 45 761 966 | 42 074 | 2.53 |

| Burundi | 11 179 000 | 751 | 14 673 682 | 19 547 | 1.31 |

| Cameroon | 23 344 000 | 1505 | 115 191 263 | 76 543 | 4.93 |

| Cape Verde | 521 000 | 4 | 642 650 | 149 761 | 1.23 |

| Central African Republic | 4 900 000 | 742 | 12 132 085 | 16 357 | 2.48 |

| Chad | 14 037 000 | 1659 | 106 702 194 | 64 305 | 7.60 |

| Comoros | 788 000 | 20 | 727 391 | 35 531 | 0.92 |

| Congo Republic of | 4 620 000 | 175 | 26 065 572 | 148 966 | 5.64 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 22 702 000 | 2758 | 231 097 654 | 83 803 | 10.18 |

| DRC | 77 267 000 | 7298 | 140 486 238 | 19 250 | 1.82 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 845 000 | 47 | 42 493 865 | 895 595 | 50.29 |

| Eritrea | 5 228 000 | 279 | 6 786 209 | 24 350 | 1.30 |

| Ethiopia | 99 391 000 | 7315 | 338 483 350 | 46 275 | 3.41 |

| Gabon | 1 725 000 | 107 | 47 986 750 | 447 687 | 27.82 |

| Gambia The | 1 991 000 | 68 | 2 574 353 | 37 974 | 1.29 |

| Ghana | 27 410 000 | 1150 | 119 008 952 | 103 489 | 4.34 |

| Guinea | 12 609 000 | 1271 | 34 402 618 | 27 069 | 2.73 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 844 000 | 95 | 3 193 144 | 33 478 | 1.73 |

| Kenya | 46 050 000 | 1469 | 114 657 578 | 78 047 | 2.49 |

| Lesotho | 2 135 000 | 29 | 1 897 047 | 66 004 | 0.89 |

| Liberia | 4 503 000 | 192 | 3 459 176 | 18 030 | 0.77 |

| Madagascar | 24 235 000 | 1017 | 38 131 704 | 37 481 | 1.57 |

| Malawi | 17 215 000 | 554 | 13 198 778 | 23 832 | 0.77 |

| Mali | 17 600 000 | 1009 | 43 813 514 | 43 425 | 2.49 |

| Mauritania | 4 068 000 | 154 | 14 928 594 | 97 022 | 3.67 |

| Mauritius | 1 273 000 | 7 | 3 212 952 | 441 942 | 2.52 |

| Mozambiqu | 27 978 000 | 1543 | 41 035 562 | 26 597 | 1.47 |

| Namibia | 2 459 000 | 18 | 4 305 273 | 234 472 | 1.75 |

| Niger | 19 899 000 | 1428 | 27 871 413 | 19 517 | 1.40 |

| Nigeria | 182 202 000 | 13 944 | 1 625 450 009 | 116 572 | 8.92 |

| Rwanda | 11 610 000 | 408 | 17 313 494 | 42 472 | 1.49 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 190 000 | 3 | 185 766 | 65 785 | 0.98 |

| Senegal | 15 129 000 | 474 | 28 758 809 | 60 629 | 1.90 |

| Seychelles | 96 000 | 1 | 496 645 | 683 843 | 5.17 |

| Sierra Leone | 6 453 000 | 665 | 23 115 300 | 34 786 | 3.58 |

| South Africa | 54 490 000 | 882 | 232 433 738 | 263 625 | 4.27 |

| South Sudan | 12 340 000 | 3013 | 124 210 140 | 41 228 | 10.07 |

| Swaziland | 1 287 000 | 23 | 4 630 328 | 197 374 | 3.60 |

| Tanzania | 53 470 000 | 2278 | 175 770 061 | 77 176 | 3.29 |

| Togo | 7 305 000 | 443 | 15 077 774 | 34 028 | 2.06 |

| Uganda | 39 032 000 | 2344 | 112 108 332 | 47 836 | 2.87 |

| Zambia | 16 212 000 | 618 | 48 509 819 | 78 483 | 2.99 |

| Zimbabwe | 15 603 000 | 346 | 16 826 522 | 48 696 | 1.08 |

| Djibouti | 888 000 | 34 | 2 285 624 | 67 853 | 2.57 |

| Egypt | 91 508 000 | 630 | 169 948 068 | 269 620 | 1.86 |

| Libya | 6 278 000 | 35 | 9 714 196 | 278 383 | 1.55 |

| Morocco | 34 378 000 | 175 | 35 758 333 | 204 524 | 1.04 |

| Sudan | 40 235 000 | 4184 | 432 348 755 | 103 325 | 10.75 |

| Tunisia | 11 254 000 | 34 | 8 963 687 | 266 963 | 0.80 |

The value of human life lost per NTDD was Int$ 231 278 for Group 1, Int$ 109 771 for Group 2 and Int$ 37 489 for Group 3. The mean value of human life lost per person in the population was Int$ 5.6 for Group 1, Int$ 5.8 for Group 2 and Int$ 2.6 for Group 3 (see Table 4). The mean value of human life lost per NTDD in Group 1 was over two times that of Group 2 and almost six times that of Group 3.

The main determinant of expected value of human life lost is the magnitude of GDP per person. For instance, even if deaths in Group 1 countries such as Botswana, Libya, Mauritius and Seychelles were only 22, 35, 7 and 1, respectively, the value of human life lost per NTDD for these countries were considerable at Int$ 341 854 for Botswana, Int$ 278 383 for Libya, Int$ 441 942 for Mauritius and Int$ 683 843 for Seychelles. Group 3 countries with comparatively higher number of NTDDs such as for the DRC with 7298 deaths, Ethiopia with 7315 deaths, South Sudan with 3013 deaths and Uganda with 2344 deaths have relatively lower values of human life lost per NTDD of Int$ 19 250, Int$ 46 275, Int$ 41 228 and Int$ 47 836, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis results

The use of a 5% discount rate resulted in a reduction in the total value of human life loss of Int$ 1 446 559 015 (28.3%) and the mean value of human life loss per NTDD by Int$ 21 317. Application of a 10% discount rate reduced the overall total value of human life loss by Int$ 3 030 347 733 (59.3%) and the mean value of human life loss per NTDD by Int$ 44 656.

Discussion

The estimated total value of human life loss attributed to NTDDs is about 0.1% of the 2015 GDP of the 53 African countries. As demonstrated by the sensitivity analysis, the magnitude of the total value of human life loss hinges on the discount rate [73–75].

The total value of human life loss attributed to NTDDs is higher than the Int$ 1.69 billion for diabetes in Africa [72]. However, it was lower than that the Int$ 5.53 billion for maternal mortality and Int$ 50.4 billion for tuberculosis deaths in Africa [75, 76].

It may be argued that there is not much point to continue investing in NTDs, which cause a relatively lower number of deaths and productivity losses compared to, for example, maternal mortality and tuberculosis mortality. Such critiques should take into account that while NTDs are not a major cause of death, they have life-long debilitating effects on health-related quality of life of populations living in endemic areas [91–95], educational achievements of children, worker productivity and agricultural outputs [6, 92, 96, 97].

There are six main arguments for continued (and probably increased) investment to control, eliminate and eventually eradicate NTDs. First, in line with the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is the right of every person living in NTD-endemic areas to have unconstrained access to all effective preventive and treatment interventions [98, 99]. Thus, we concur with Molyneux [100] that the “continuing advocacy for the relevance of control or elimination of NTDs must be placed in the context of universal health coverage and access to donated essential medicines for the poor as a [human] right” (p. 1).

Second, the resources required for implementing the regional strategic plan for eliminating NTDs in the African region have been estimated at US$ 2.57 billion over a six-year period, which translates to US$ 428.33 million per year [101, 102]. This cost of implementing national-level “NTD Master Plans” for controlling NTDs is by far much lower than our estimated NTD-related productivity losses of Int$ 5.1 billion.

Third, effective medicines for treating all NTDs are available and a sufficient amount of donated drugs has been pledged by their manufacturers to meet the needs in endemic countries [102, 103].

Fourth, even though NTDs are not a major cause of death, every year they lead to a substantive loss of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in Africa. For example, the WHO estimated that in 2015, the African continent lost 10.3 million DALYs due to neglected parasitic diseases and intestinal nematodes [104].

Fifth, global and continental plans and programmes for combating NTDs exist. They provide detailed guidance on the cost-effective NTD interventions that individual countries should invest in. These plans include: the WHO global strategy 2015–2020 on water, sanitation and hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on neglected tropical diseases [105]; regional strategy on NTDs [106]; regional strategic plan for NTDs [106]; roadmap for accelerating work to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases [107]; and the global plan to combat neglected tropical diseases 2008–2015 [108]. In 2015, the Expanded Special Project for Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases was established in Africa [109].

Sixth, continental and global political commitment exists for ending the morbidity and mortality from NTDs. In January 2014, the Twenty-Fourth Ordinary Session of the African Union Executive Council adopted the Continental Framework on the Control and Elimination of NTDs in Africa by 2020 and committed to using it for developing and revising national NTD plans [110]. In 2013, the World Health Assembly, through resolution WHA66.12, adopted a comprehensive global strategy for combatting NTDs [111]. In the same year, the Sixty-Third Regional Committee for Africa through resolution AFR/RC63/R6 adopted both the regional strategy and the strategic plan on NTDs [112]. The African Union decisions and WHO Regional Committee for Africa resolutions urge African countries and their partners to commit more resources and use them efficiently to implement the Continental Framework on the Control and Elimination of NTDs through national NTD plans.

Limitations

There are seven broad limitations of the current study. First, some costs were omitted. For example, direct costs of NTD prevention programmes, and diagnosis and treatment services were not taken into account because the current study focused on years of life lost due to premature mortality. The study also excluded the indirect costs of productive labour time lost due to morbidity, including cost of time spent seeking treatment, reduced level of performance of activities/functions of daily living, and time expended by caregivers (family and friends) and those accompanying the sick to sources of care, e.g. health facilities, private pharmaceutical shops, traditional healers. The intangible/psychological costs related to stigmatisation, discrimination, pain, anxiety and bereavement were also omitted.

Second, to date there is no consensus in the published literature on the discount rate that should be applied in health sector studies. In this study, we used discount rate of 3%, which has been applied frequently in past health-related studies [81, 113–115].

Third, there is no agreement in literature about whether mortality occurring at different age groups should be weighted differently. In our study, we assumed all life to be intrinsically valuable and thus a year lost in an age group was considered to be of equal value [116]. This is why the current study used per-capita GDP to value YLLs at any age group.

Fourth, various authors have underscored a few weaknesses inherent in the use of per-capita GDP as a measure of societal economic and wellbeing: (a) per-capita GDP is an average value, which is distorted by high-income earners and corporate supernormal profits, and does not reflect distribution of income, consumption and wealth [117]. Therefore, if a country’s GDP distribution is skewed, a small wealthy class can increase per-capita GDP substantially while the majority of the population does not experience any economic and social progress [117]. (b) Per-capita GDP does not factor in the negative externalities of goods and services production and delivery processes, e.g. depletion of natural resources, air pollution from carbon emissions of airplanes and vehicles, global warming, and contamination of water with industrial waste [117]. (c) The value of household and other unpaid work is not measured in the system of national accounts that produces GDP. A substantial burden of unpaid domestic work (preparing food, cleaning and maintaining the home) and unpaid care work (care a person provides to their own family and household members) in Africa is borne by women [118–121]. We concur with Hirway [121] that the exclusion of unpaid domestic and caring work from national accounts and from the conventional economy is not justifiable, as both contribute to the conventional economy.

Fifth, a number of weaknesses characterise the lost output approach or HCA: (a) It assumes that the objective of health care is getting sick people back to productive employment. However, there are other objectives, such as preventing morbidity and death so that people can enjoy life (flourish), enjoy leisure and perform non-economic societal functions, etc. (b) In its pure form, the HCA would value the lives of pensioners (elderly), full-time homemakers and non-working children at zero. In this study, we value all lives using per-capita GDP prevailing in each country. (c) The HCA does not capture intangible psychological costs of NTDs, e.G. stigma, pain, bereavement, anxiety and suffering [122, 123].

Sixth, the values of life loss estimates reported in this paper are not a guide to setting priorities in the research, prevention and treatment of NTDs [124, 125]. The estimated value of human lives lost due to NTDs are only meant for use in raising public awareness and advocacy with ministries of finance in African countries on the magnitudes of potential economic losses arising from mortality associated with NTDs. Therefore, we are cognisant of the fact that setting priorities in NTD research, prevention and treatment must be guided by economic evaluation evidence on costs and consequences of competing research, prevention and treatment strategies [81, 82].

Seventh, it is common knowledge that vital registration systems in many countries in Africa are either non-existent or very weak. That is why the deaths and burden of disease estimates reported by international organisations are often projections based on second-best approaches. Thus, it is usually not possible to verify the coverage and quality of secondary mortality data among the analysed countries.

Conclusions

Even though NTDs are not a major cause of death, they impact negatively on the productivity of those affected throughout their life-course. Thus, the case for investing in NTD control should also be influenced by the value of NTD morbidity, availability of effective donated medicines, human rights arguments and need to achieve the NTD-related target 3.3 of the UN SDG 3 (on health) by 2030.

In order for the African continent to have a fair chance of ending the epidemic of NTDs by 2030, as envisioned in SDG 3, the national governments, African Union, Regional Economic Communities and all partners need to continue fighting the war against NTDs until they are all controlled, eliminated, eradicated and eventually extinct from the continent. As long as corruption and lack of accountability remain endemic due to weak leadership [126–129] and governance [130–132], the war against NTDs (and other causes of ill-health) is unlikely to be won. Thus, African governments and development partners need to continue their efforts to fully implement the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action [133] to ensure strategic policy frameworks exist and are combined with effective integration, coordination, oversight (to assure efficiency), coalition building, the provision of appropriate regulations and incentives, attention to system-design and accountability [134–136].

Additional files

Multilingual abstracts in the five official working languages of the United Nations. (PDF 392 kb)

Number of NTD deaths in Africa in 2015. (DOCX 13 kb)

WHO Global Health Estimates of Frontier Years of Life Lost (not age weighted or discounted). (DOCX 12 kb)

Non-health GDP per capita. (DOCX 13 kb)

Illustration of estimation of value of human life lost in a country. (DOCX 310 kb)

Acknowledgements

Jehovah-Jireh met all our needs in the process of writing this paper. We dedicate this article to all those who died prematurely from NTDs; all those living with NTDs; the African Union (and its organs) and Regional Economic Communities; the WHO; and all the leaders, health workers, communities, researchers, educators, journal editors and health development partners who are unremittingly fighting to make NTDs extinct in Africa. This paper contains solely the views of the authors and does not represent the views or policies of the Meru University of Science and Technology.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during this study are outlined in the attached Additional Files.

Additional file 2: Number of NTDDs in Africa in 2015.

Additional file 3: Life expectancies and YLLs per country in Africa in 2015.

Additional file 4: Non-health GDP per capita in Africa in 2015.

Abbreviations

- GDPPCInt$

Per capita GDP in international dollars

- NHGDPPCInt$

Per capita non-health GDP in PPP

- VHLLost0 − 4

Value of human lives lost among those aged 0–4 years

- VHLLost15 − 29

Value of human lives lost among those aged 15–29 years

- VHLLost30 − 49

Value of human lives lost among those aged 30–49 years

- VHLLost50 − 59

Value of human lives lost among those aged 50–59 years

- VHLLost5 − 14

Value of human lives lost among those aged 5–14 years

- VHLLost60 − 69

Value of human lives lost among those aged 60–69 years

- VHLLost≥70

Value of human lives lost among those aged 70 years and above

- DALY

Disability-adjusted life year

- DRC

Democratic Republic of the Congo

- GDP

Gross domestic product

- ILO

International Labour Organization

- IMF

International Monetary Fund

- Int$

International dollars

- NTD

neglected tropical disease

- NTDD

NTD death

- PCTHE

Per-capita total health expenditure

- PPP

Purchasing power parity

- r

Rate of discount of future losses

- UN

United Nations

- VHLLost

Value of human lives lost

- WHO

World Health Organization

- YLL

Year of life lost

Authors’ contributions

JMK and GNM designed the study, conducted the literature review, analysed the data and wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study did not involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue. It was based completely on secondary statistical data published on the WHO and IMF websites.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40249-017-0379-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.World Bank. Country and lending groups – country classification. Washington, D.C. 2016. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 30 Nov 2016.

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) World Health Statistics 2016. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook Database. Washington, D.C. 2016. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/weorept.aspx? Accessed 7 Feb 2017.

- 4.WHO. Global Health estimates 2015: Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000-2005. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

- 5.Remme JHF, Feenstra P, Lever PR, Medici AC, Morel CM, Noma M, et al. Tropical diseases targeted for elimination: Chagas disease, lymphatic Filariasis, Onchocerciasis, and leprosy. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 433–450. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris J, Adelman C, Spantchak Y, Marano K. Social and economic impact review on neglected tropical diseases. Washington, D.C.: Hudson Institute’s Center for Science in Public Policy & The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases an initiative of the Sabin Vaccine Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotez PJ, Fenwick A, Savioli L, Molyneux DH. Rescuing the bottom billion through control of neglected tropical diseases. Lancet. 2009;373:1570–1575. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO . First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases: working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO . Sustaining the drive to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: second WHO report on neglected diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Research Council . The causes and impacts of neglected tropical and Zoonotic diseases: opportunities for integrated intervention strategies - workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels F, Pose R. Why neglected tropical disease matter in reducing poverty. Development progress. Working paper 03. London: ODI; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quansah E, Sarpong E, Karikari TK. Disregard of neurological impairments associated with neglected tropical diseases in Africa. eNeurologicalSci. 2016;3:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.African Union (AU) Neglected tropical diseases in the Africa region. Sixth conference of AU ministers of health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 22–26 April 2013. Addis Ababa: AU; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations (UN) Seventieth session of the United Nations general assembly resolution a/RES/70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: UN; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frick KD, Basilion E, Hanson C, Colchero M. Estimating the burden and economic impact of trachomatous visual loss. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10(2):121–132. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.2.121.13899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frick KD, Hanson CL, Jacobson GA. Global burden of trachoma and economics of the disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69((5) suppl 1):1–10. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.69.5_suppl_1.0690001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramaiah KD, Das PK, Michael E, Guyatt H. The economic burden of lymphatic filariasis in India. Parasitol Today. 2000;16(6):251–253. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boelaert M, Meheus F, Robays J, Lutumba P. Socio-economic aspects of neglected tropical diseases: sleeping sickness and visceral leishmaniasis. Pathog Glob Health. 2010;104(7):535–542. doi: 10.1179/136485910X12786389891641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King CH, Dickman K, Tisch DJ. Reassessment of the cost of chronic helminthic infection: a meta-analysis of disability-related outcomes in endemic schistosomiais. Lancet. 2005;365:1561–1569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meltzer M. Using disability adjusted life years to assess the economic impact of dengue in Puerto Rico: 1984-1994. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59(2):265–271. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Allmen SD, Lopez-Correa RH, Woodall JP, Morens DM, Chiriboga J, Casta-Valez A. Epidemic dengue fever in Puerto Rico, 1977: a cost analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:1040–1044. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouri GP, Guzman MG, Bravo JR, Triana C. Dengue haemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: lessons from the Cuban epidemic, 1981. Bull World Health Organ. 1989;67:375–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sornmani S, Okanurak K, Indaratna K. Social and economic impact of dengue haemorrhagic fever in Thailand. Bangkok: Social and Economic Research Unit, Mahidol University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyapong JO, Gyapong M, Evans DB, Aikins MK, Adjei S. The economic burden of lymphatic filariasis in northern Ghana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90(1):39–48. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meheus F, Abuzaid AA, Baltussen R, Younis BM, Balasegaram M, Khalil EAG, et al. The economic burden of visceral Leishmaniasis in Sudan: an assessment of provider and household costs. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(6):1146–1153. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rijal S, Koirala S, Stuyft PV, Boelaert M. The economic burden of visceral leishmaniasis in Nepal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(9):839–841. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knobel DL, Cleaveland S, Coleman PG, Fevre EM, Meltzer MI, Miranda MEG, et al. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:360–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogochukwu I, Onwujekwe O, Uzochukwu B, Ajuba M, Okonkwo P. Exploring consumer perceptions and economic burden of onchocerciasis on households in Enugu state, south-East Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(11):e0004231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: a computational simulation model. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(4):342–348. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandler DJ, Hansen KS, Mahato B, Darlong J, John A, Lockwood DNJ. Household costs of leprosy reactions (ENL) in rural India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(1):e0003431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw APM. Economics of African trypanosomiais. In: Maudlin I, Holmes PH, Miles MA, editors. The Trypanosomiasis. London: CAB International; 2004. pp. 369–402. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conteh L, Engels T, Molyneux D. Socioeconomic aspects of neglected tropical diseases. Lancet. 2010;375:239–247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright WH. A consideration of the economic impact of schistosomiasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47(5):559–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mooney GH. Valuing human life in health service delivery policy. Nuffield/York portfolios. Folio 3. Nuffield: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1983. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linnerooth J. The value of human life: a review of the models. Econ Inq. 1979;17(1):52–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1979.tb00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mooney GH. The valuation of human life. London: Macmillan; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones-Lee MW. The value of life and safety. Amsterdam: North Holland; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petty W. Political Arithmetrick, or a discourse concerning the extent and value of lands, people, buildings, etc. London: Robert Caluel. p. 1699.

- 39.Fein R. Economics of mental illness. New York: Basic Books; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mushkin SJ, Collings FA. Economic costs of disease and injury. Public Health Rep. 1959;74:795–809. doi: 10.2307/4590578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisbrod B. Costs and benefits of medical research: a case study of poliomyelitis. J Political Econ. 1971;79:527–544. doi: 10.1086/259766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landefeld JS, Seskin EP. The economic value of life: linking theory to practice. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:555–566. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.72.6.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoque ME, Mannan M, Long KZ, Al Mamun A. Economic burden of underweight and overweight among adults in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review. Tropical Med Int Health. 2016;21(4):458–469. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yesudian CAK, Grepstad M, Visintin E, Ferrario A. The economic burden of diabetes in India: a review of the literature. Glob Health. 2014;10:80. doi: 10.1186/s12992-014-0080-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD. Low Back Pain in Australian Adults: The Economic Burden. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2003;15(2):79–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Dror DM, Putten-Rademaker OV, Koren R. Cost of illness: evidence from a study in five resource-poor locations in India. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:347–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.John RM, Sung H-Y, Max W. Economic cost of tobacco use in India, 2004. Tob Control. 2009;18:138–143. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng Y, Ji L, Wu J. Cost-of-illness studies of diabetes mellitus in China: a systematic review. Chin J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;28(10):821–825. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hosung S, Suehyung L, Soo KJ, Jinsuk K, Hong HK. Socioeconomic costs of food-borne disease using the cost-of-illness model: applying the QALY method. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010;43(4):352–361. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2010.43.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper GJS, Scott DJ. The cost of diabetes in South Auckland. N Z Med J. 1985;98(773):113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott WG, White HD, Scott HM. Cost of coronary heart disease in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 1993;106(962):347–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alzheimer’s New Zealand, Access Economics . The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand. Wellington: Arthritis New Zealand; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Easton B. The social costs of tobacco use and alcohol misuse. Wellington: Wellington School of Medicine, Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand and Public Health Commission; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anis AH, Zhang W, Bansback N, Guh DP, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL. Obesity and overweight in Canada: an updated cost-of-illness study. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Claubaugh G, Ward MM. Cost-of-illness studies in the United States: a systematic review of methodologies used for direct cost. Value Health. 2008;11:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U. S. in 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):596–615. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, Adams E, Cronin K, Goodman C, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(5):1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolf AM, Colditz GA. Current estimates of the economic cost of obesity in the United States. Obes Res. 1998;6(7):97–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rice DP. Estimating the costs of illness. Am J Public Health. 1967;57:424–440. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.57.3.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hartunian NS, Smart CN, Thompson MS. The incidence and economic costs of cancer, motor vehicle injuries, coronary heart disease, and stroke: a comparative analysis. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:1249–1260. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.70.12.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leal J, Luengo-Fernandez R, Sullivan R, Witjes JA. Economic burden of bladder cancer across the European Union. Eur Urol. 2016;69(3):438–447. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luengo-Fernandez R, Burns R, Leal J. Economic burden of non-malignant blood disorders across Europe: a population-based cost study. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3(8):e371–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gordois AL, Toth PP, Quek RG, Proudfoot EM, Paoli CJ, Gandra SR. Productivity losses associated with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):759–769. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2016.1259571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ignatyeva VI, Derkach EV, Avxeentyeva MV, Omelyanovsky VV. The cost of melanoma and kidney, prostate, and ovarian cancers in Russia. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014;4C:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klimes J, Vocelka M, Sedova L. Medical and productivity costs of rheumatoid arthritis in the Czech Republic: cost-of-illness study based on disease severity. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014;4C:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hillemanns P, Breugelmans JG, Gieseking F, Benard S, Lamure E, Littlewood KJ, et al. Estimation of the incidence of genital warts and the cost of illness in Germany: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirigia JM, Sambo LG, Yokouide A, Soumbey-Alley E, Muthuri LK, Kirigia DG. Economic burden of cholera in the WHO African region. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orem JN, Kirigia JM, Azairwe R, Kasirye I, Walker O. Impact of malaria morbidity on gross domestic product in Uganda. Int Arch Med. 2012;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chima RI, Goodman C, Mills A. The economic impact of malaria in Africa: a critical review of the evidence. Health Policy. 2003;63:17–36. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barnett TA, Whiteside A, Desmond C. The social and economic impact of HIV/AIDS in poor countries: a review of studies and lessons. Prog Dev Stud. 2001;1:151–170. doi: 10.1191/146499301701571426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Russell S. The economic burden of illness for households in developing countries: a review of studies focusing on malaria, tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kirigia JM, Sambo HB, Sambo LG, Barry SP. Economic burden of diabetes mellitus in the WHO African region. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kirigia JM, Muthuri RDK, Nabyonga-Orem J, Kirigia DW. Counting the cost of child mortality in the World Health Organization African region. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1103. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2465-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kirigia JM, Masiye F, Kirigia DW, Akweongo P. Indirect costs associated with deaths from the Ebola virus disease in West Africa. Infect Dis Poverty. 2015;4:45. doi: 10.1186/s40249-015-0079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kirigia JM, Muthuri RDK. Productivity losses associated with tuberculosis deaths in the World Health Organization African region. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:43. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0138-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kirigia JM, Mwabu GM, Orem JN, Muthuri RDK. Indirect cost of maternal deaths in the WHO African region, 2013. Int J Soc Econ. 2016;43(5):532–548. doi: 10.1108/IJSE-05-2014-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fourie FCN. How to think and reason in macroeconomics. Cape Town: Juta & Co.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mooney MH. Economics, medicine and health care. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 79.WHO . WHO guide to identifying the economic consequences of disease and injury. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chisholm D, Stanciole AE, Edejer TTT, Evans DB. Economic impact of disease and injury: counting what matters. BMJ. 2010;340(c924):583–586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kirigia JM. Economic evaluation of public health problems in sub-Saharan Africa. Nairobi: University of Nairobi Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Drummond MF, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Curry S, Weiss J. Project analysis in developing countries. London: The MacMillan Press LTD; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 84.WHO . WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000–2015. Global Health estimates technical paper WHO/HIS/IER/GHE/2016.3. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 85.WHO . WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000–2015. Global Health estimates technical paper WHO/HIS/IER/GHE/2017.1. Geneva: WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 86.International Labour Organization (ILO) C138 - minimum age convention, 1973 (no. 138) Geneva: ILO; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 87.WHO. Global Health expenditure database, Geneva. 2017. http://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/Indicators/en. Accessed 7 Feb 2017.

- 88.Murray CJL. Rethinking DALYs. In: Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease - a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 89.WHO . World health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murray CJL, David B. Health systems performance assessment: debates, methods and empiricism. Geneva: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Adenowo AF, Oyinloye BE, Ogunyinka BI, Kappo AP. Impact of human schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fenwick A. Neglected tropical diseases: can we take the ‘neglected’ out of the name? A Global Village. Imperial College International Affairs J. 2010;2:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hollingsworth TD, Adams ER, Anderson RM, Atkins K, Bartsch S, Basáñez M-G, et al. NTD Modelling consortium: quantitative analyses and modelling to support achievement of the 2020 goals for nine neglected tropical diseases. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:630. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1235-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cattand P, Desjeux P, Guzmán MG, Jannin J, Kroeger A, Médici A, et al. Tropical diseases lacking adequate control measures: Dengue, Leishmaniasis, and African Trypanosomiasis. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries (DCP2) New York: The World Bank and Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 451–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hotez PJ, Bundy DAP, Beegle K, Brooker S, Drake L, de Silva N, et al. Helminth infections: soil-transmitted Helminth infections and Schistosomiasis. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries (DCP2) New York: The World Bank and Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lenk EJ, Redekop WK, Luyendijk M, Rijnsburger AJ, Severens JL. Productivity loss related to neglected tropical diseases eligible for preventive chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats . The causes and impacts of neglected tropical and Zoonotic diseases: opportunities for integrated intervention strategies. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.UN . Universal declaration of human rights. New York: UN; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 99.WHO . Neglected diseases: a human rights analysis. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Molyneux DH. Neglected tropical diseases: now more than just ‘other diseases’ – the post-2015 agenda. Int Health. 2014;6(3):172–180. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihu037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa (WHO/AFRO) Regional strategy on neglected tropical diseases in the WHO African region: 2014–2020. Brazzaville: WHO/AFRO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Seddoh A, Onyeze A, Gyapong JO, Holt J, Bundy D. Towards an investment case for neglected tropical diseases - including new analysis of the cost of intervening against preventable NTDs in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet commission on investing in health working paper. London: Lancet; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Uniting to Combat NTDs . London declaration on neglected tropical diseases. Ending the neglect and reaching 2020 goals. London: Uniting to Combat NTDs; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 104.WHO . Global Health estimates 2015: DALYs by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2015. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 105.WHO . Water, sanitation and hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on neglected tropical diseases: a global strategy 2015–2020. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.WHO/AFRO . Regional strategic plan for neglected tropical diseases in the African region 2014–2020. Brazzaville: WHO/AFRO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 107.WHO . Accelerating work to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: a roadmap for implementation. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 108.WHO . Global plan to combat neglected tropical diseases 2008–2015. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 109.WHO/AFRO . Framework for the establishment of the expanded special project for elimination of neglected tropical diseases. Brazzaville: WHO/AFRO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 110.African Union. Decision on the report of the sixth session of the conference of African union ministers of health and report of the fifth meeting of the African task force on food and nutrition development. The executive council decision EX.CL/Dec.795(XXIV). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: AU; 2014.

- 111.WHO . Neglected tropical diseases. Sixty-sixth world health assembly resolution WHA66.12. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 112.WHO/AFRO . Regional strategy on neglected tropical diseases in the WHO African region. Sixty-third Regional Committee for Africa Resolution AFR/RC63/R6. Brazzaville: WHO/AFRO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease in 1990: final results and their sensitivity to alternative epidemiological perspectives, discount rates, age-weights and disability weights. In: Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease. Geneva: WHO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kirigia JM. The economics of Schistosomiasis interventions: a case study of the Mwea irrigation scheme in Kenya. Doctor of philosophy thesis. York: University of York; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 115.World Bank . World development report, 1993: investing in health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 116.The Ghana Health Assessment Team A quantitative method of assessing the health impact of different diseases in less developed countries. Int J Epidemiol. 1981;10:73–80. doi: 10.1093/ije/10.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P. Report of the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: The Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nancy F. The invisible heart: economics and family values. New York: New Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nancy F. Holding hands at midnight: the paradox of caring labour. Fem Econ. 1995;1(1):73–92. doi: 10.1080/714042215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Luisella GC. Economic valuations of unpaid household work: Africa, Asia, Latin America and Oceania. In: women, work and development. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hirway I. Unpaid work and the economy: linkages and their implications. J Labor Econ. 2015;58(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s41027-015-0010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Saha S, Gerdtham UG. Cost of illness studies on reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: a systematic literature review. Health Econ Rev. 2013;3:24. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Weiss MG. Stigma and the social burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(5):e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wiseman V, Mooney G. Burden of illness estimates for priority setting: a debate revisited. Health Policy. 1998;43(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(98)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shiell A, Gerard K, Donaldson C. Cost of illness studies: an aid to decision-making? Health Policy. 1987;8(3):317–323. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(87)90007-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rispel LC, de Jager P, Fonn S. Exploring corruption in the south African health sector. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(2):239–249. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mostert S, Njuguna F, Olbara G, Sindano S, Sitaresmi MN, et al. Corruption in health-care systems and its effect on cancer care in Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):e394–e404. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.World Bank . Africa development indicators 2010: silent and lethal, how quiet corruption undermines Africa’s development efforts. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Transparency International . Global corruption report 2006: corruption and health. London: Pluto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kirigia JM. The essence of leadership in health development. Afr J Health Sci. 2008;15(1–2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Uneke CJ, Ezoeha AE, Ndukwe CD. Enhancing leadership and governance competencies to strengthen health systems in Nigeria: assessment of organizational human resource development. Healthc Policy. 2012;79(3):73–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kirigia JM, Kirigia DG. The essence of governance in health development. Int Arch Med. 2011;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.OECD . The Paris declaration on aid effectiveness and the Accra agenda for action. Paris: OECD; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 134.WHO . Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 135.African Union & WHO . Commitment on accountability mechanism to assess the implementation of commitments made by African ministers of health (AUC-WHO/COM.6/2014). First meeting of African ministers of health jointly convened by the AUC and WHO Luanda, Angola, 16–17 April, 2014. Addis Ababa: AU; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kirigia JM, Diarra-Nama AJ. Can countries of the WHO African region wean themselves off donor funding for health? Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:889–895. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.054932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multilingual abstracts in the five official working languages of the United Nations. (PDF 392 kb)

Number of NTD deaths in Africa in 2015. (DOCX 13 kb)

WHO Global Health Estimates of Frontier Years of Life Lost (not age weighted or discounted). (DOCX 12 kb)

Non-health GDP per capita. (DOCX 13 kb)

Illustration of estimation of value of human life lost in a country. (DOCX 310 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during this study are outlined in the attached Additional Files.

Additional file 2: Number of NTDDs in Africa in 2015.

Additional file 3: Life expectancies and YLLs per country in Africa in 2015.

Additional file 4: Non-health GDP per capita in Africa in 2015.