Abstract

Background

There is paucity of data on prevalence of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) and adherence and clinical outcomes of antidepressants. The present study determined the magnitude of ADRs of antidepressants and their impact on the level of adherence and clinical outcome.

Methods

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted among depression patients from September 2016 to January 2017 at Gondar University Hospital psychiatry clinic. The Naranjo ADR probability scale was employed to assess the ADRs. The rate of medication adherence was determined using Morisky Medication Adherence Measurement Scale-Eight.

Results

Two hundred seventeen patients participated in the study, more than half of them being males (122; 56.2%). More than one-half of the subjects had low adherence to their medications (124; 57.1%) and about 186 (85.7%) of the patients encountered ADR. The most common ADR was weight gain (29; 13.2%). More than one-half (125; 57.6%) of the respondents showed improved clinical outcome. Optimal level of medication adherence decreased the likelihood of poor clinical outcome by 56.8%.

Conclusion

ADRs were more prevalent. However, adherence to medications was very poor in the setup. Long duration of depression negatively affects the rate of adherence. In addition, adherence was found to influence the clinical outcome of depression patients.

1. Introduction

Major Depression (MD) is the most common mental health problem in the world. Life time prevalence of 16.2% million among adults has been reported in United States [1]. The scale of global impact of mental illness is substantial, constituting an estimated 7.4% of the world's measurable burden of disease [2]. Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) globally and ranks among the four largest contributors to YLDs [2]. In economic terms, a study commissioned by the World Economic Forum concluded that the world encountered a cumulative output loss of $47 trillion between 2011 and 2030 due to noncommunicable diseases and mental illness [3].

In Ethiopia different studies among varying groups of participants reported a range of findings. In the northern part of the country, the burden of depression was found to be about 17.5% among community dwellers [4]. Another study among women attending antenatal care in a teaching referral hospital reported a 23% prevalence [5]. Prevalence of the disease among epileptic patients in northwest Ethiopia was estimated to be 45.2% [6]. A systematic review, which determined a pooled prevalence of the diseases in Ethiopia, reported a prevalence of 6.8% [7]. As to the mortality caused by depression, a population based study determined that the mortality rate of the disease was 3.5% [8]. Etiologies such as psychological, biological, and environmental factors contributed to its prevalence [9].

Once it happened, depression requires a due attention to treat or hold its progression. The management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) requires the combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs) medications are the common pharmacologic agents [10]. The coincidence of depression along with other clinical characteristics such as psychotic and bipolar features requires initiation of combination medication which predisposes patients to Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs). After initiation of antidepressants, a significant number of patients report ADRs. Self-reported ADRs encompass spontaneous reporting or easy probing by health care providers [11]. Different types of ADRs have been reported due to antidepressant. A study among elderly inpatients in Italy demonstrated that cardiovascular and arrhythmic complications and gastrointestinal ADRs were the most common ones. It showed that ADRs were associated with frequency of depression and women were found to suffer higher incidence of depression and mostly affected by ADRs [12].

Though patients report untoward effect of medications, the temporal-relationship of ADR with the drug is established by the utilization of standard tools [13]. ADRs affect the compliance of patients to their medications. A study in the USA reported participants with worrying side-effects tended to be nonadherent to their antidepressant medications [14]. The efficacy of antidepressants, on the other hand, is affected by the rate of adherence to medications. A review article revealed that nonadherence remains a major challenge in achieving good clinical outcomes [15]. Another review reported uncontrolled depression also might lead to medication discontinuation [16]. In addition, factors such sex, age, and duration of illness and side-effects were associated with level of adherence [17]. Hence, medication safety, efficacy, and level of adherence are considered to be interrelated [18].

Despite the interdependency of the above parameters, there is paucity of data that reveal the impact of ADRs on the level of medication adherence in patients with depression in developing setting. Investigation of the magnitude of ADRs, medication adherence, and clinical outcome will provide a clue to design coping strategies against the most deleterious ADRs based on severity and probability of the ADR. In addition, determination of the overall adherence and clinical status of patients would enable evaluating the effectiveness of our interventions. Hence, the present study sought to determine the level of adherence to and clinical outcome of antidepressants and magnitude of their ADRs. In addition, the study has also aimed to identify factors affecting adherence and clinical outcome in depression patients attending psychiatry clinic of referral and teaching hospital.

2. Patients and Methods Study Setting and Design

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Gondar University Hospital (GUH) from September 2016 to January 2017. GUH is a teaching referral hospital that serves more than 5 million people in northwest Ethiopia. It has both inpatient and outpatient departments. The medical outpatient department comprised chronic disease clinics including psychiatry unit. The psychiatry clinic provides inpatient service to admitted patients and the outpatients for follow-up of bipolar, depression, substance abuse and schizophrenic patients.

2.1. Study Subjects and Population

All depression patients that do have regular visit at GUH constituted our source population. Patients who have been taking antidepressant for at least one month were included in the study.

2.2. Study Variables

Level of adherence to antidepressants, patient clinical outcome, and ADRs were our primary end points whereas sociodemographic characteristics of the patient including age, gender, residence, distance from hospital, and disease duration were the independent variables.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.3.1. Data Collection Tools

The Naranjo ADR probability scale, which contains ten items, was employed to assess the ADRs due to antidepressants. Based on the scale, ADR is considered to be definite if the score is ≥9, probable if the score is 5–8, possible if the score is 1–4, and doubtful if the score is 0 [19]. The Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist (ASEC) which was developed by Royal College of Psychiatrists was applied to classify the MSE into mild, moderate, and sever [20]. In addition, the type of ADR reported by the patient was reported from ASEC as all ADRs have been listed in ASEC. Clinical outcomes of patients were assessed by using patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) developed by Kroenke and Spitzer and adopted to our setup [21]. According to these criteria, patients' status was classified as mild, moderate, moderately sever, and severe depression by presenting nine questions that have bothered patients in the last two weeks. To make the clinical outcome a dichotomous categorical variable, patients were classified as “improved” by combining mild and moderate and “not improved” (moderately severe and severe depression), based on the PHQ-9. The rate of medication adherence (MA) was determined using Morisky Medication Adherence Measurement Scale-Eight (MMAS-8). According to this scale a score less than six indicates low adherence, a score of 6-7 moderate level of adherence, and a score of 8 high level of adherence. In this study, high adherence was considered optimal adherence and low and medium adherence were defined as suboptimal adherence [22]. All tools were translated in Amharic version and showed reliability of more than 80% (Cronbach alpha).

2.3.2. Data Collection Process

Data was collected by clinical psychiatrist using a pretested structured data collection tool. The data collector was trained intensively on contents of questionnaire, data collection methods, and ethical concerns. The data collector utilized a face-to-face interview with patients. Data collection has been conducted in both the inpatient and outpatient clinic of GUH. Patients were requested to report only the one most annoying ADR during the last one month.

2.4. Data Analysis

All the statistical data were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 21 (SPSS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented using means with standard deviation (±SDs) and percentages (%). P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Multivariable logistic regression was carried out to determine factors for MA and clinical outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

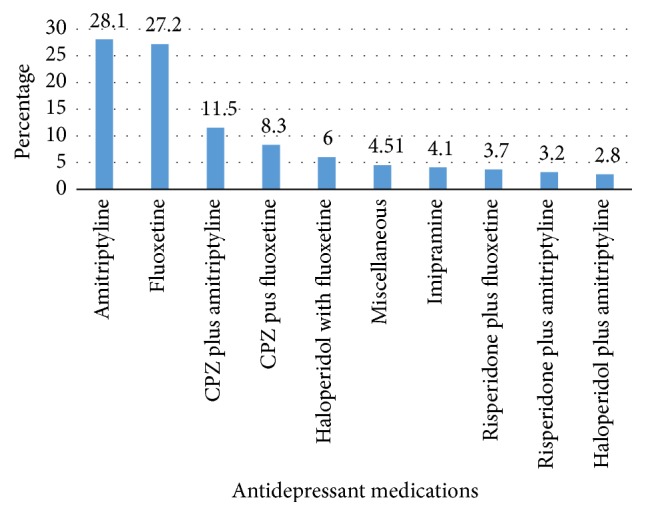

Two hundred seventy patients participated in the study giving a 100% response rate. More than half of the respondents were males (122; 56.2%). The mean age of the participants was 30.94 ± 8.85. About 125 (57.6%) of them came from urban area. The majority of the patients were farmers and laborers (75; 34.6). Nearly forty percent of them complete some college or university education (91; 41.9%). The mean duration of the disorder was 1.67 ± 0.948 years. The prevalence of comorbid disorder was 13 (6.0%). Diabetes and human immune virus (HIV) were the most common ones. The mean distance in hours from the hospital was 1.027 ± 0.78 hr. Around 125 (57.6%) had improved outcome. The most common prescribed monotherapy medication was amitriptyline (61; 28.1%) followed by fluoxetine (59; 27.2%). Combination of chlorpromazine plus amitriptyline (25; 11.5%) was frequently prescribed dual therapy. More than one-half of 125 (57.6%) patients had concomitant psychiatric illness. The most common comorbid psychiatric condition was MDD with psychotic feature (16.61%) whereas the list coincident was MDD with manic episodes (3.7%) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the respondents.

| Variables | Frequency N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 30.94 ± 8.853 |

| Male | 122 (56.2%) |

| Duration of the disease | 1.67 ± 0.948 yrs |

| Urban | 125 (57.6%) |

| Education, college and university | 91 (41.9%) |

| Occupation, labor | 75 (34.6) |

| Distance (mean ± SD) | 1.027 ± 0.78 hr |

| Comorbidity | 13 (6.0%) |

| Comorbid psychiatric features (n = 125) | |

| Depression with psychotic feature | 40 (18.4%) |

| Depression with GAD | 36 (16.61%) |

| Depression with otherwise not specified characteristics | 17 (7.8%) |

| Depression with manic episode | 32 (14.7%) |

CPZ: chlorpromazine, generalized anxiety disorder.

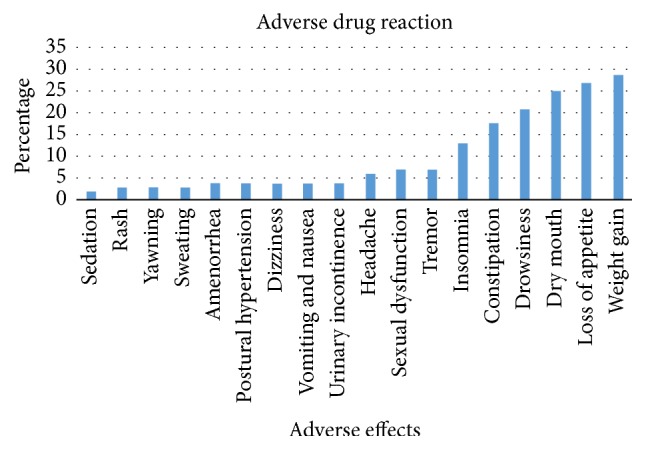

Figure 1.

The frequency of patient reported side-effects (n = 217).

3.2. Level of Medication Adherence

The mean level of adherence was 4.74 ± 2.19 out of eight scores. More than one-half of the subjects had low adherence to their medications (124; 57.1%). Nearly one-third of them had moderate adherence (70; 32.3%). Only 23 (10.6%) of them achieve high adherence level.

3.3. Adverse Drug Reaction

About 186 (85.7%) of patients encountered ADR. The most common ADR was weight gain (29; 15.59%) followed by loss of appetite (27; 14.52%). Sedation was rarely reported ADR (2; 1.1%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Antidepressant medications.

3.4. ADR Severity Score and Naranjo Probability Scale

According to ASEC majority of the ADRs were moderate (150; 69.1%), followed by severe (33; 15.2) and mild (3; 1.4%). Based on Naranjo score, about 198 (92.2%) ADRs were probable and 19 (8.8%) were possible (Table 2).

Table 2.

Severity and probability of ADRs.

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Severity | |

| Mild | 3 (1.4) |

| Moderate | 150 (69.1) |

| Sever | 33 (15.2) |

| Probability | |

| Probable | 198 (92.2) |

| Possible | 19 (8.8) |

3.5. Factors Associated with Medication Adherence

According to bivariate analysis, age, education, work, and comorbidity were not found to be correlated with the dependent variable. Patients with long duration of disease (above two years) were 2.5 times more likely to be nonadherence, adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 2.424 [1.185–4.961], and those who came from long distance were found to be five times nonadherent to their medications as compared to short distance, AOR: 5.061 [1.792–14.928]. Patients with concomitant psychiatric illness tended to be more nonadherent, AOR: 2.228 [1.009–4.518] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with medication adherence.

| Variable | Level of adherence | Crude OR [95% CI] |

Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal | Suboptimal | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 55 (25.34) | 67 (30.88) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 38 (17.51) | 57 (26.26) | 1.231 [0.715–2.121] | 1.103 [0.551–2.208] |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 72 (33.18) | 53 (24.42) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 21 (9.68) | 71 (42.72) | 4.593 [2.515–8.389]∗ | 2.008 [0.933–4.32] |

| Disease duration | ||||

| Less than two years | 51 (23.03) | 41 (18.89) | 1 | 1 |

| More than two years | 42 (19.35) | 83 (9.68) | 2.458 [4.413–4.227]∗∗ | 2.424 [1.185–4.961]∗ |

| Distance | ||||

| <2 hours | 82 (37.78) | 71 (32.72) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥2 hours | 11 (5.10) | 53 (24.42) | 5.565 [2.701–11.466]∗∗ | 5.061 [1.792–14.928]∗ |

| Other psychiatric illness | ||||

| Yes | 40 (18.43) | 85 (39.17) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 53 (24.42) | 39 (17.97) | 2.888 [1.652–5.049]∗∗ | 2.228 [1.009–4.518]∗ |

| Naranjo score | ||||

| Possible | 12 (5.53%) | 7 (3.22%) | 1 | 1 |

| Probable | 56 (28.80%) | 112 (51.61%) | 3.429 [1.279–9.188]∗ | 2.838 [0.923–8.701] |

| Severity of ADR | ||||

| Moderate | 59 (27.18%) | 91 (41.93) | 1 | 1 |

| Sever | 8 (3.69%) | 28 (12.90) | 2.269 [0.969–5.319] | 1.172 [0.422–3.254] |

∗Statistically significant at 0.05. ∗∗Significant at 0.01.

More than one-half (125; 57.6%) of respondents showed improved outcome. Optimal level of medication adherence decreased the likelihood of poor clinical outcome by 56.8%, AOR: 0.432 [0.201–0.909], whereas female gender increases the likelihood of poor outcome by threefold as compared to males, AOR: 2.919 [1.527–5.279] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with the clinical outcome.

| Variable | Treatment outcome | Crude OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (125; 57.6%) | Unimproved (92; 42.4%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 83 (38.25) | 39 (17.97) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 42 (19.35) | 53 (24.42) | 2.686 [1.541–4.681]∗∗ | 2.919 [1.527–5.279]∗∗ |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 74 (34.01) | 51 (23.51) | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 51 (23.50) | 41 (18.89) | 1.166 [0.677–2.010] | 0.812 [0.380–1.734] |

| Disease duration | ||||

| Less than two years | 41 (18.89) | 51 (23.50) | 1 | 1 |

| More than two years | 84 (15.47) | 41 (18.89) | 0.392 [0.225–1.684] | 0.249 [0.122–1.508] |

| Distance | ||||

| <2 hours | 94 (43.32) | 59 (27.19) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥2 hours | 31 (14.29) | 33 (15.21) | 1.333 [0.49–2.686] | 1.367 [0.603–3.099] |

| Other psychiatric illnesses | ||||

| Yes | 68 (43.31) | 57 (26.26) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 57 (26.26) | 35 (16.13) | 1.365 [0.789–2.363] | 0.824 [0.414–1.642] |

| Naranjo score | ||||

| Possible | 10 (4.60) | 9 (4.15) | 1 | Ref |

| Probable | 91 (41.93) | 77 (35.48) | 0.940 [0.363–2.432] | 0.898 [0.303–2.669] |

| Level of adherence | ||||

| Optimal | 62 (28.57) | 31 (14.28) | 0.37 [0.110–5.379]∗ | 0.432 [0.201–0.909]∗ |

| Suboptimal | 63 (29.03) | 61 (28.11) | 1 | 1 |

| Severity of ADR | ||||

| Moderate | 86 (39.63) | 64 (29.49) | 1 | 1 |

| Sever | 14 (6.45) | 22 (10.14) | 2.112 [1.003–4.444]∗ | 2.133 [0.912–4.990] |

∗Statistically significant at 0.05. ∗∗Significant at 0.01.

4. Discussion

Depression is one of the common psychiatric illnesses which requires adequate medical treatment. Initiation of antidepressant along with psychotherapy is expected to alleviate symptoms. However, the clinical outcome depends on patients' persistence with medications with no significant apparent ADRs. The present study assessed three interrelated issues including self-reported ADRs, medication adherence, and clinical outcomes of patients receiving antidepressants. This study has found that ADRs were more prevalent in MDD patients as above eighty percent of the respondents reported ADRs. Nearly twenty types of ADRs were identified. The most common ADR was weight gain which might be due to the prescription of tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline [23]. Moreover, our study has found that the most common prescribed monotherapy medication was amitriptyline (61; 28.1%) followed by fluoxetine (59; 27.2%). Older generation antidepressants are associated with wide range of side-effects and they are commonly prescribed in Ethiopia due to reduced cost. These traditional medications were also given in combination. For instance, combination of chlorpromazine plus amitriptyline (25; 11.5%) was frequently prescribed dual therapy. In addition to different classes of antidepressants, the lack of improvement of the disease might contribute to the weight bearing effect of the disease [24]. The self-reported ADRs including weight gain should be given attention because more than ninety percent of them were probably due to the medications according to the Naranjo ADR probability scale. The underreporting of side-effects such as sexual dysfunction by depression patients could lead to nonadherence and poor improvement which increases suicidal ideation [25]. Even though the majority of them were mild to moderate, it requires reassurance of the patients so as to maintain high medication adherence which could be achieved with collaborative care [26].

In this study, only one-tenth of subjects achieved adequate medication adherence. The rate of adherence was also low among depression patients in Thailand [27]. A ten-year cumulative evidence reported that approximately fifty percent of depression patients discontinue their medications [28]. Sriharsha (2015) has reported that various factors such as duration of therapy and disease were found to influence adherence [29]. Our study has also found that long-standing depression and comorbid psychiatric features increased the chance of nonadherence. Another study from India also identified that nonadherence was higher among female participants which revealed the same finding with the present study [30]. According to a result of patient survey, individual side-effects including weight gain and being unable to orgasm were associated with nonadherence [20, 31]. However, the current study was not able to assess correlation with respect to each type of ADRs due to violation of assumptions of logistic regressions; rather the level of adherence was not found to be associated with the probability and severity of ADRs. Other factors play a pivotal role in predicting adherence in the set. Whenever depression occurs with other unspecified psychiatric features, there might be misdiagnosis of one or more components which could lead to undertreatment and nonadherence [32]. In addition, long duration of disease remains to be an important determinant for poor adherence; this is due to the lack of improvement of the disease which might make patient lose belief in the effectiveness of their medications. Overall, to address these challenges and to achieve optimal medication adherence, application of adherence-enhancement interventions is vital [33]. In addition, adherence to medications could be promoted by the establishment of close communication between the patient and the physician [27].

More than fifty percent of patients attained optimal control of the disease in the present study. In contrast to this, another study reported low rate of remission among major depression patients attending primary care. This might be due to the difference in the level of care, therapeutic alternatives, and scale of measurements of the clinical outcome [34]. In our study, the optimal antidepressant medication adherence decreases the incidence of poor treatment outcome. Gender difference also has been observed in terms of achieving improved outcome. Accordingly, females tended to have poor outcome compared to males. This might be due to undiagnosed past history of sexual assaults among females. According to previous reports sexual assault was considered to be correlated with poor outcome [35]. In addition, biological factors such as postnatal depression might pose significant barriers to treatment outcome among women [36]. In our study clinical outcome was measured only at a single visit; hence the frequency of relapse was not determined. Evidences have indicated that a significant number of patients who achieved remission developed a relapse [37]. Investigation of clinical outcome of more than one visit would enable designing more effective interventions for patients who do not show robust improvement in treatment. These interventions include the implementation of nonpharmacologic psychotherapy that has been shown to provide more benefits over pharmacotherapy alone [38].

Generally, this study highlighted the extent of adherence, clinical outcomes, and prevalence of patient reported ADRs. However, it is limited to single center and the current sample size decreases the power of the study to determine associating factors of adherence and clinical outcomes. The authors call for a large multicenter study which evaluates clinical outcome based on comparative effectiveness of antidepressants and by measuring clinical outcome in subsequent visits.

5. Conclusion

The current study identified that patient reported ADRs were highly prevalent among MDD patients, weight gain being the most common. Adherence to medications was very poor in the hospital which was attributed to factors such as long-standing depression, distance from the follow-up clinic, and comorbid psychiatric illness. In addition, clinical outcome of patients was affected by nonadherence to antidepressant medications. The authors recommend that clinicians implement adherence enhancing interventions for their patients. Moreover, further research would establish that ADRs, adherence, and clinical outcome influence each other. Furthermore patients should be asked for ADRs so as to insure the safety of antidepressants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge University of Gondar for allowing conducting this study, and, in addition, the Department of Psychiatry Clinic for overall support.

Abbreviations

- ADR:

Adverse Drug Reaction

- AOR:

Adjusted odds ratio

- ASEC:

Antidepressant Side-Effect Check list

- COR:

Crude Odds Ratio

- GUH:

Gondar University Hospital

- MA:

Medication adherence

- MDD:

Major Depressive Disorder

- MMAS-8:

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-Eight

- MSE:

Medication Side-Effect

- PHQ-9:

Patient Health Questionnaire-Nine

- PR-ADR:

Patient Reported Adverse Drug Reaction

- SNRI:

Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- SSRI:

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- TCA:

Tricyclic antidepressant

- YLD:

Years lived with disability.

Additional Points

Availability of Data and Material. Supplementary data could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted after ethical clearance letter was received from research and ethics review committee of school of pharmacy, University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Science.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to participation.

Disclosure

The abstract of this study was submitted to the 19th International Conference on Mental Health which was conducted in Berlin, Germany, on May 21-22, 2017.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Tadesse Melaku Abegaz conceived the study, prepared the study protocol, did the analysis, and wrote the final version of the manuscript. Lamessa Melese Sori designed the questionnaire, reviewed the manuscript, and participated in data collection, Hussien Nurahmed Toleha did the data entry and was involved in data analysis and manuscript write-up. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kessler R. C., Berglund P., Demler O., et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker A. E., Kleinman A. Mental health and the global agenda. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(1):66–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1110827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter D. J., Reddy K. S. Noncommunicable diseases. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(14):1336–1343. doi: 10.1056/nejmra1109345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molla G. L., Sebhat H. M., Hussen Z. N., Mekonen A. B., Mersha W. F., Yimer T. M. Depression among ethiopian adults: cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Journal. 2016;2016:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2016/1468120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayele T. A., Azale T., Alemu K., Abdissa Z., Mulat H., Fekadu A. Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression among women attending antenatal care service at gondar university hospital, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155125.e0155125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bifftu B. B., Dachew B. A., Tiruneh B. T., Birhan Tebeje N. Depression among people with epilepsy in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional institution based study. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(1, article no. 1515) doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1515-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitew T. Prevalence and risk factors of depression in Ethiopia: a review. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2014;24(2):161–169. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v24i2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mogga S., Prince M., Alem A., et al. Outcome of major depression in Ethiopia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:241–246. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.013417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein B., Rosselli F. Etiological paradigms of depression: The relationship between perceived causes, empowerment, treatment preferences, and stigma. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12(6):551–563. doi: 10.1080/09638230310001627919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connolly K. R., Thase M. E. Emerging drugs for major depressive disorder. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 2012;17(1):105–126. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2012.660146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakkarainen K. M., Andersson Sundell K., Petzold M., Hägg S. Prevalence and Perceived Preventability of Self-Reported Adverse Drug Events - A Population-Based Survey of 7099 Adults. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073166.e73166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onder G., Penninx B. W. J. H., Landi F., et al. Depression and adverse drug reactions among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2003;163(3):301–305. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milane M. S., Suchard M. A., Wong M.-L., Licinio J. Modeling of the temporal patterns of fluoxetine prescriptions and suicide rates in the United States. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(6):0816–0824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamburrino M. B., Nagel R. W., Chahal M. K., Lynch D. J. Antidepressant medication adherence: A study of primary care patients. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;11(5):205–211. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman S. C. E., Horne R. Medication nonadherence and psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2013;26(5):446–452. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283642da4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiMatteo M. R., Lepper H. S., Croghan T. W. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Jumah K., Hassali M. A., Al Qhatani D., El Tahir K. Factors associated with adherence to medication among depressed patients from Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2014;10:2031–2037. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S71697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho P. M., Rumsfeld J. S., Masoudi F. A., et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2006;166(17):1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naranjo C. A., Busto U., Sellers E. M. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1981;30(2):239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uher R., Farmer A., Henigsberg N., et al. Adverse reactions to antidepressants. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):202–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):509–515. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yue Z., Li C., Weilin Q., Bin W. Application of the health belief model to improve the understanding of antihypertensive medication adherence among Chinese patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2015;98(5):669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berilgen M. S., Bulut S., Gonen M., Tekatas A., Dag E., Mungen B. Comparison of the effects of amitriptyline and flunarizine on weight gain and serum leptin, C peptide and insulin levels when used as migraine preventive treatment. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(11):1048–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merikangas A. K., Mendola P., Pastor P. N., Reuben C. A., Cleary S. D. The association between major depressive disorder and obesity in US adolescents: Results from the 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35(2):149–154. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins A., Nash M., Lynch A. M. Antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: Impact, effects, and treatment. Journal of Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety. 2010;2(1):141–150. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson T. J., Fortney J. C., Pyne J. M., Lu L., Mittal D. Reduction of patient-reported antidepressant side effects, by type of collaborative care. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66(3):272–278. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawada N., Uchida H., Suzuki T., et al. Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: A chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9, article no. 38 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sansone R. A., Sansone L. A. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 2012;9(5-6):41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sriharsha M. A. P. Treatment and disease related factors affecting non-adherence among patients on long term therapy of antidepressants. Journal of Depression and Anxiety. 2015;4(2) doi: 10.4172/2167-1044.1000175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee S., Varma R. P. Factors affecting non-adherence among patients diagnosed with unipolar depression in a psychiatric department of a tertiary hospital in Kolkata, India. Depression Research and Treatment. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/809542.809542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashton A. K., Jamerson B. D., Weinstein W. L., Wagoner C. Antidepressant-related adverse effects impacting treatment compliance: Results of a patient survey. Current Therapeutic Research - Clinical and Experimental. 2005;66(2):96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothschild A. J. Challenges in the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39(4):787–796. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Servellen G., Heise B. A., Ellis R. Factors associated with antidepressant medication adherence and adherence-enhancement programmes: A systematic literature review. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2011;8(4):255–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelsey J. E. Achieving remission in major depressive disorder: the first step to long-term recovery. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2004;104(3):p. -10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cort N. A., Gamble S. A., Smith P. N., et al. Predictors of treatment outcomes among depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(6):479–486. doi: 10.1002/da.21942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Mahen H. A., Grieve H., Jones J., McGinley J., Woodford J., Wilkinson E. L. Women's experiences of factors affecting treatment engagement and adherence in internet delivered Behavioural Activation for Postnatal Depression. Internet Interventions. 2015;2(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitiello B., Emslie G., Clarke G., et al. Long-term outcome of adolescent depression initially resistant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: A follow-up study of the TORDIA sample. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):388–396. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05885blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sofia S., Gérard S., Brigitte H., Catherine V., Maria S., Alexandros P., et al. 8th Santorini Conference: Systems medicine and personalized health and therapy, Santorini, Greece, 3–5 October 2016. Official journal of the European Society of Pharmacogenomics and Personalised Therapy. 2017;32(2) doi: 10.1515/dmpt-2016-0030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]