Abstract

Introduction

In Los Angeles County, about 25% of men who have sex with men (MSM) are unaware of their HIV positive status.

Methods

An advertisement publicizing free HIV self-tests was placed on Grindr™, a smartphone social networking application, from April 17 to May 29, 2014. Users were linked to http://freehivselftests.weebly.com/ to choose a self-test delivery method: U.S. mail, a Walgreens® voucher, or from a vending machine. Black or Latino MSM ≥ 18 years old were invited to take a testing experiences survey.

Results

During the campaign, the website received 11,939 unique visitors (average: 284 per day) and 334 self-test requests. Among 57 survey respondents, fifty-five (97%) reported using the self-test was easy; two persons reported testing HIV positive and both sought medical care.

Conclusions

Social networking application self-testing promotion resulted in a large number of self-test requests and has high potential to reach untested high-risk populations who will link to care if positive.

Keywords: Grindr, mobile apps, MSM, HIV, self-testing

INTRODUCTION

In Los Angeles County, men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV infection, accounting for 84% of all HIV diagnoses (Division of HIV and STD Programs, 2014). Among MSM, Blacks/African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos experience higher incidence rates and have lower percentages of serostatus awareness and linkage to care than any other racial/ethnic group (Prejean et al., 2011; Sharma, Stephenson, White, & Sullivan, 2014). The racial disparity in HIV incidence may be explained in part by the high proportions of unrecognized and untreated HIV infections among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM (MacKellar et al., 2005). Increasing HIV serostatus awareness by expanding HIV testing efforts in high-risk groups is critical to reduce ongoing HIV transmission and the number of new infections (Pinkerton, Holtgrave, & Galletly, 2008).

Engaging Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM in HIV testing has been challenging because of the high prevalence of HIV-related stigma in these communities and limited access to physician or community-based HIV testing sites (Brooks, Etzel, Hinojos, Henry, & Perez, 2005; Mahajan et al., 2008; Millett, Malebranche, Mason, & Spikes, 2005; Young, Shoptaw, Weiss, Munjas, & Gorbach, 2011). Increased use of self-testing using oral fluid rapid HIV tests might reduce the stigma associated with HIV testing, improve access and increase testing rates. Those tests allow individuals to conduct their oral fluid rapid tests and interpret their results in the privacy of their own homes. Although concerns about affordability have been raised, HIV self-tests have been found to be acceptable in high-risk communities (Carballo-Diéguez, Frasca, Balan, Ibitoye, & Dolezal, 2012; Myers et al., 2014). Optimizing uptake of HIV self-tests could play an important role in increasing the frequency of testing among previously untested Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM.

Recent studies by our team evaluated the use of electronic vending machines and vouchers as potential delivery models for HIV self-tests (Marlin et al., 2014; Young SD, 2014). Both using vending machines to dispense HIV tests and distributing vouchers redeemable for an HIV test were found to be feasible delivery models that were also acceptable among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM (Marlin et al., 2014; Young SD, 2014). However, the best way to reach MSM and link them to those delivery models has not been assessed.

The expansion of information and communication technologies, including smartphone applications, provide the potential for delivering health interventions to hard-to-reach populations, especially those who may not access in-person programs. In particular, the rapid increase in mobile phone and online social networking usage among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM, is creating new opportunities for HIV prevention and testing efforts targeting these groups (Jaganath, Gill, Cohen, & Young, 2012; Muessig et al., 2013; Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project, 2013; Young et al., 2013). MSM were early adopters of the Internet for sex-seeking purposes (Klausner, Wolf, Fischer-Ponce, Zolt, & Katz, 2000; McFarlane, Bull, & Reitmeijer, 2000), and many MSM now use their mobile phones to meet sexual partners as well as access health information (Muessig et al., 2013). New smartphone social networking applications like Grindr™, SCRUFF, and Jack’d, which allow MSM to find potential new sexual partners based on geographical proximity, have been found effective at reaching and recruiting MSM for HIV prevention research (Burrell et al., 2012; Landovitz et al., 2013; Martinez et al., 2014). These applications represent possible venues through which to promote HIV self-testing.

An innovative HIV testing strategy that addresses common barriers, including poor access, stigma, and cost, is needed. This study evaluated an HIV testing program that linked social networking advertisements with an online test request system to distribute HIV self-tests to Black and Latino MSM in Los Angeles.

METHODS

Social Networking Advertisements

From April 17 to May 29, 2014, we placed advertisements publicizing free HIV self-testing kits on Grindr™, a smartphone geosocial networking application available on iOS and Android [Figure 1]. Grindr™ users were able to access our study website by clicking through: (1) a broadcast message shown as a pop-up the first time users logged on to the application within a 24-hour period; or (2) a banner advertisement shown continuously to users while they were logged on to the application. Both the broadcast messages and the banner advertisements were only visible to Grindr™ users who logged on to the application in the specific geographic regions of West Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles. The broadcast messages were displayed to all Grindr™ users logging on within the 24-hour periods of April 23, April 28, May 5, and May 11, 2014, while the banner advertisements were displayed 300,000 times from April 17 to May 29, 2014.

Figure 1.

A banner advertisement displayed on a smartphone

Online Test Request System

Grindr™ users who clicked on an advertisement were directed to our study website (http://freehivselftests.weebly.com/), where they were asked to choose one of three methods for self-test delivery: (1) USPS mail, (2) a Walgreens voucher, or (3) from a vending machine. After indicating their preference, all website visitors were invited to participate in an online research study on HIV self-testing, and were subsequently presented with an online informed consent form. Interested visitors who provided consent were assigned a study ID and directed to a baseline survey, which gathered data on demographics, recent sexual history, HIV testing history, and alcohol and drug use. Eligible study participants were aged ≥ 18 years who self-identified as Black/African American or Hispanic/Latino MSM. Computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses were tracked, and multiple survey entries from the same IP address were not accepted.

HIV Self-Test Delivery

All website visitors who submitted a test request through our study website, regardless of their study participation status, received one free OraQuick® In-Home HIV Test via their preferred delivery method. For visitors who chose the mail delivery method, tests were sent using USPS Priority Mail® to visitor-provided mailing addresses. Test delivery was confirmed through USPS Delivery Confirmation™. Visitors who requested a Walgreens voucher were emailed a printable, double-sided voucher that could be redeemed for one free test at participating Walgreens stores in West Hollywood and Los Angeles. Each voucher was encoded with a unique number that allowed us to track where and when it was redeemed. Visitors who preferred the vending machine option were sent a unique, one-time use personal identification number (PIN) code that could be used to dispense one free test at a customized UCapIt™ machine located in the parking lot of the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center. PIN code usage was tracked using web-based software.

Follow-Up Surveys

Two weeks after confirming mailed test delivery, voucher redemption, or PIN code usage, eligible study participants were sent hyperlinks via email or SMS asking them to complete a follow-up survey on their home self-testing experience. Using Likert scales, participants were asked to rate the ease of use of the HIV self-test, as well as the comfort, convenience/ease of use, and overall satisfaction of the test delivery method they chose. Study participants were also asked about their test result, linkage-to-care activities, and HIV testing preferences. Follow-up and baseline survey entries were linked using the participant’s study ID.

Data Collection and Analysis

The surveys were administered using the online survey assessment tool SurveyMonkey. Survey responses were collected over secured, encrypted SSL connections. All protected health information (PHI) was coded with unique study IDs available only to the researchers. Coded data were stored and secured on a password-protected network folder that was accessed only by password-protected computers with firewalls. Google Analytics was used to track and measure website traffic. Baseline and follow-up survey data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

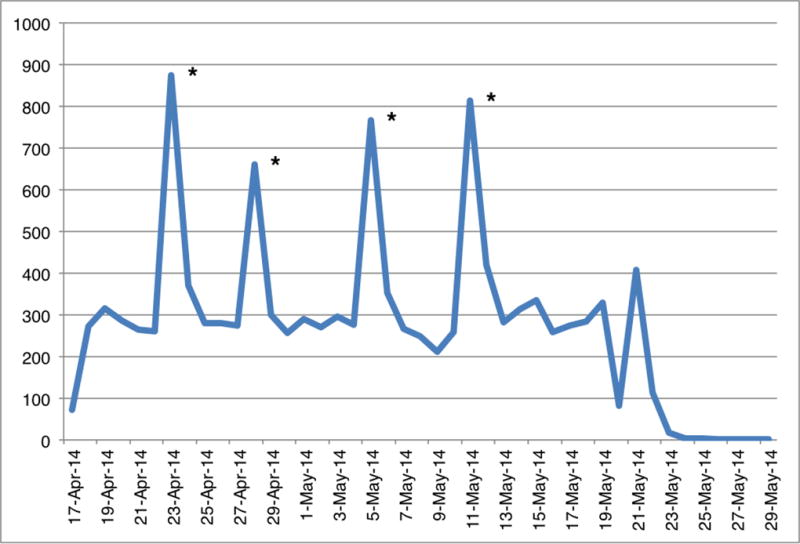

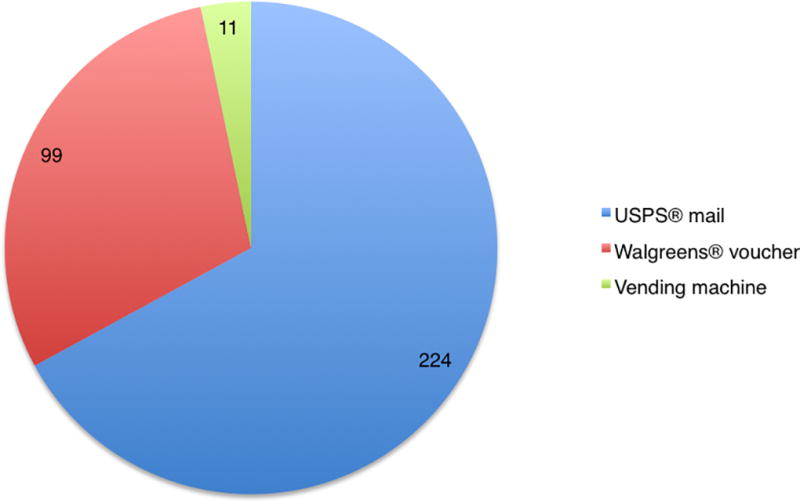

In 2014, Grindr™ had 349,000 Los Angeles users, 6% of whom identified as Black and 12% as Latino. This results in 62,820 Black and Latino users who saw our advertisements. Over the six-week advertisement period, four broadcast messages and 300,000 banner advertisement impressions were delivered, and the study website received 11,939 unique visitors (average: 284 per day) [Figure 2], yielding an overall click-through rate of 2.8%. Of the 334 total test requests received, 224 (67%) were requests for mailed tests, 99 (30%) were for vouchers, and 11 (3%) were to use the vending machine [Figure 3]. A total of 238 website visitors were interested in participating in the study and completed the baseline survey; 122 (51.3%) met our eligibility criteria (i.e., MSM aged ≥ 18 years self-identifying as Black/African American or Hispanic/Latino) and were enrolled in the study.

Figure 2.

Daily number of unique visits to the HIV self-test program website (17 Apr – 29 May)

* The peaks in the graph correspond to dates on which broadcast messages were displayed.

Figure 3.

Number of HIV self-test kit requests by delivery method

Among the 122 study participants [Table 1a], 64.8% were between 18–30 years old, 13.9% identified as Black/African American, 86.1% identified as Hispanic/Latino, 61.5% had tested for HIV in the past year, 27.9% last tested over a year ago, and 10.7% had never tested. A high proportion (91.0%) of participants reported at least one episode of condomless anal sex in the past three months, with an average of 2.8 condomless anal sex acts in the past three months.

Table 1.

| a: HIV Self-Test Program Study Participant Characteristics (N=122), Los Angeles, 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Survey response | Total |

| Age (years): | |

| 18–30 | 79 (65%) |

| 31–40 | 31 (25%) |

| 41+ | 12 (10%) |

| Race/Ethnicity: | |

| Black/African American | 17 (14%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 105 (86%) |

| Highest level of education: | |

| Less than high school | 6 (5%) |

| High school | 28 (23%) |

| Greater than high school | 88 (72%) |

| Number of condomless receptive anal sex acts in past three months: | |

| None | 64 (52%) |

| 1–3 | 43 (35%) |

| 4+ | 15 (12%) |

| Number of condomless insertive anal sex acts in past three months: | |

| None | 55 (45%) |

| 1–3 | 42 (34%) |

| 4+ | 25 (20%) |

| History of STD diagnosis: | |

| Yes | 41 (34%) |

| No | 80 (66%) |

| Refuse to answer | 1 (1%) |

| Last HIV test: | |

| < 6 months | 38 (31%) |

| 6 – 12 months | 37 (30%) |

| > 12 months | 34 (28%) |

| Never | 13 (11%) |

| Illicit drug use in past year: | |

| Yes | 17 (14%) |

| No | 100 (82%) |

| Refuse to answer | 5 (4%) |

| b: HIV Self-Test Program Testing Experiences Survey (N=57), Los Angeles, 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Survey response | Total |

| Ease of use of self-test kit: | |

| Very easy | 33 (58%) |

| Easy | 22 (39%) |

| Neutral | 2 (4%) |

| Hard | 0 (0%) |

| Very hard | 0 (0%) |

| Reported self-test result: | |

| Negative | 55 (96%) |

| Positive | 2 (4%)1 |

| Testing preference: | |

| Prefer self-test kit | 25 (44%) |

| Somewhat prefer self-test kit | 14 (25%) |

| Neutral | 7 (12%) |

| Somewhat prefer a clinic | 9 (16%) |

| Prefer a clinic | 2 (4%) |

Both respondents who reported a positive self-test result also reported seeking confirmatory testing or medical care.

Two-thirds of the participants (81/122) were confirmed to have received a self-test and were invited to complete a follow-up survey. None of the five vending machine PIN codes given out were used; therefore, survey responses specific to the vending machine delivery option are not included in the analyses.

Among 57 participants who completed the follow-up survey, 53 (93%) received a test by mail and 4 (7%) redeemed a voucher for a test. Table 1b shows 55 (96.5%) reported using the self-test was easy or very easy, and 39 (68.4%) would prefer self-testing among other testing choices in the future; 55 (96.5%) reported testing HIV negative, and two (3.5%) reported newly testing HIV positive. Both persons with positive test results reported seeking confirmatory testing or medical care. There was high satisfaction with both the mail and voucher delivery methods.

The differences in baseline characteristics between participants who completed the follow-up survey and those who did not were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The growth of information and communication technologies during the last decade has brought new opportunities and challenges in public health. Previous work has demonstrated the importance of using those technologies to reach MSM of color and other high-risk groups with HIV prevention and health promotion messages (Burrell et al., 2012; Holloway et al., 2014; Jaganath et al., 2012; D Levine, McCright, Dobkin, Woodruff, & Klausner, 2008; DK Levine, Scott, & Klausner, 2005; D Levine, Woodruff, Mocello, Lebrija, & Klausner, 2008; Martinez et al., 2014; McFarlane, Kachur, Klausner, Roland, & Cohen, 2005; Muessig et al., 2013; Young et al., 2013). Our study, which created a program centered on an emerging mobile networking technology, is a natural extension of those efforts.

Our findings suggest that an HIV self-testing program that links social network advertising to an online self-test request system was successful at reaching Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM in Los Angeles County. Our program yielded a new HIV positivity rate of 3.5%, performing better than routine HIV testing in clinics (0.8%) as well as newer methods such as HIV testing in bathhouses and sex clubs (3.0%), mobile HIV testing units (0.8%), and storefront HIV testing (1.1%) (Division of HIV and STD Programs, 2013). The rate found in our study is on par with that among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM integrated across multiple testing modalities (3.1%) (Division of HIV and STD Programs, 2013).

Consistent with other studies, we found Grindr™ to be an effective tool for the recruitment and engagement of a high-risk MSM population (Burrell et al., 2012; Landovitz et al., 2013; Martinez et al., 2014). Our geo-targeted advertising campaign required minimal technical expertise to launch, and resulted in 334 MSM interested in participating in a six-week period. Compared to national HIV surveillance data, the participants in our study had lower rates of testing for HIV in the past year (71.1% nationally vs. 61.5% in our study) and of ever testing (93.4% vs. 89.3%), suggesting that using Grindr™ is a potential way to reach a greater proportion of MSM who might benefit from more frequent testing (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

We found that the use of freely available web-based tools was sufficient to create a fully functional online self-test request system. Development of our study website through the free web hosting service Weebly required minimal coding knowledge, and website traffic and visitor information was easily tracked using Google Analytics. All communication with participants, including email and SMS, was performed using Google services. The online component of our program incurred little to no costs; the major costs to the program were incurred by cost of the self-test kits, the staff time required to manage the program, and the postage needed to fulfill mail delivery requests.

We found a high acceptability for in-home self-testing for HIV infection among high-risk Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino MSM, which is consistent with studies of testing preferences among MSM, as well as a high preference for USPS mail delivery (Raymond, Bingham, & McFarland, 2008; Sharma et al., 2014). Given that the mail delivery method was the only model that was purely web-based and did not require any in-person action from the participant, this finding is consistent with a recent study by Holloway et al., which found that young MSM prefer online and smartphone app-based programs to in-person interventions (Holloway et al., 2014). Furthermore, we found that Grindr™ users were comfortable with disclosing personal information (i.e., name, mailing addresses, email addresses, and telephone numbers) in exchange for a free HIV self-test, which may be attributable to the perception of anonymity associated with an online environment.

Our findings also suggest that distribution of self-tests, when linked to a follow-up survey, has the potential to identify new HIV cases with linkage to care and prevention services. We successfully used the follow-up survey to capture positive testers and their linkage-to-care activities after receiving their test result. Two respondents tested positive for HIV; both reported seeking confirmatory testing or medical care.

Limitations

Because the survey responses were self-reported, the survey data may be subject to under- or over-reporting. Additionally, there was no fail proof method to verify that survey responses were unique, and it is possible that some participants were able to submit multiple survey entries. Furthermore, because the vending machine was nonfunctional for the first three weeks of the advertisement campaign, that option was only available after the mail and voucher options had started. The limited availability of the vending machine delivery method may account for the lower number of requests. There was a relatively small sample size, which limits the generalizability of our results, and no information was collected on reasons why some Grindr™ users did not enroll in the study compared to those who did.

Next Steps

HIV self-testing promotion through smartphone social networking applications has a high potential to reach untested high-risk populations who will link to care if positive. Future studies should examine expanded advertisement periods, alternative smartphone social networking applications such as SCRUFF and Jack’d, and promotion and linkage to prevention services like Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Because of the high demand for the program (more than 50 test requests per week), evaluation is ongoing. Having established the potential of using social media technologies to promote HIV testing, we will evaluate linkage to care activities among those who test positive.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Keith Daniel for assistance establishing a redemption system at Walgreens.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment (CHIPTS) NIMH grant MH58107 and the UCLA Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) grant P30AI028697. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Brooks R, Etzel M, Hinojos E, Henry C, Perez M. Preventing HIV among Latino and African American gay and bisexual men in a context of HIV-related stigma, discrimination, and homophobia: perspectives of providers. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2005;(19):737–744. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell E, Pines H, Robbie E, Coleman L, Murphy R, Hess K, Gorbach P. Use of the location-based social networking application GRINDR as a recruitment tool in rectal microbicide development research. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1816–1820. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0277-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C. Use of a rapid HIV home test prevents HIV exposure in a high risk sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;(16):1753–1760. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Infection Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors among Men Who Have Sex With Men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 U.S. Cities, 2014. [Accessed May 1, 2016];HIV Surveillance Special Report 15. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/#panel2. Published January 2016.

- Division of HIV and STD Programs. County of Los Angeles Department of Public Health, HIV Testing Services Annual Report, January through December 2011. 2013 Dec;:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Division of HIV and STD Programs. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. [Accessed May 1, 2016];Annual HIV Surveillance Report. 2013 http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/wwwfiles/ph/hae/hiv/2013AnnualHIVSurveillanceReport.pdf. Published April 2014.

- Holloway I, Rice E, Gibbs J, Winetrobe H, Dunlap S, Rhoades H. Acceptability of smartphone application-based HIV prevention among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):285–296. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0671-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaganath D, Gill H, Cohen A, Young S. Harnessing Online Peer Education (HOPE): integrating C-POL and social media to train peer leaders in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2012;24(5):593–600. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausner J, Wolf W, Fischer-Ponce L, Zolt I, Katz M. Tracing a syphilis outbreak through cyberspace. JAMA. 2000;284(4):447–449. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landovitz R, Tseng C, Weissman M, Haymer M, Mendenhall B, Rogers K, Shoptaw S. Epidemiology, sexual risk behavior, and HIV prevention practices of men who have sex with men using GRINDR in Los Angeles, California. J Urban Health. 2013;90(4):729–739. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9766-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, McCright J, Dobkin L, Woodruff A, Klausner J. SEXINFO: a sexual health text messaging service for San Francisco youth. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):393–395. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, Scott K, Klausner J. Online syphilis testing--confidential and convenient. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(2):139–141. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000149783.67826.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, Woodruff A, Mocello A, Lebrija J, Klausner J. inSPOT: the first online STD partner notification system using electronic postcards. PLoS Med. 2008;5(10):e213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar D, Valleroy L, Secura G, Behel S, Bingham T, Celentano D Group, Y. M. s. S. S. Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young men who have sex with men: opportunities for advancing HIV prevention in the third decade of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;(38):603–614. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141481.48348.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A, Sayles J, Patel V, Remien R, Ortiz D, Szekeres G, Coates T. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;(22):S67. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlin R, Young S, Bristow C, Wilson G, Rodriguez J, Ortiz J, Klausner J. Piloting an HIV self-test kit voucher program to raise serostatus awareness of high-risk African Americans, Los Angeles. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O, Wu E, Shultz A, Capote J, López Rios J, Sandfort T, Rhodes S. Still a hard-to-reach population? Using social media to recruit Latino gay couples for an HIV intervention adaptation study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e113. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane M, Bull S, Reitmeijer C. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284(4):443–446. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane M, Kachur R, Klausner J, Roland E, Cohen M. Internet-based health promotion and disease control in the 8 cities: successes, barriers, and future plans. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(10 Suppl):S60–64. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000180464.77968.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett G, Malebranche D, Mason B, Spikes P. Focusing “down low”: bisexual black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;(97):52S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muessig K, Pike E, Fowler B, LeGrand S, Parsons J, Bull S, Hightow-Weidman L. Putting prevention in their pockets: developing mobile phone-based HIV interventions for black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2013;27(4):211–222. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J, Bodach S, Cutler B, Shepard C, Philippou C, Branson B. Acceptability of Home Self-Tests for HIV in New York City, 2006. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e46–e48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project. Smartphone Ownership 2013 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton S, Holtgrave D, Galletly C. Infections prevented by increasing HIV serostatus awareness in the United States, 2001 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(3):354–357. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d57e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Lin L, Group HIS. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond H, Bingham T, McFarland W. Locating unrecognized HIV infections among men who have sex with men: San Francisco and Los Angeles. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(5):408–419. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Stephenson R, White D, Sullivan P. Acceptability and intended usage preferences for six HIV testing options among internet-using men who have sex with men. Springerplus. 2014;(3):109. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S, Shoptaw S, Weiss R, Munjas B, Gorbach P. Predictors of unrecognized HIV infection among poor and ethnic men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;(15):643–649. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S, Zhao M, Tieu K, Kwok J, Gill H, Gill N. A social-media based HIV prevention intervention using peer leaders. J Consum Health Internet. 2013;17(4):353–361. doi: 10.1080/15398285.2013.833445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SD, Daniels J, Chiu CJ, Bolan RK, Flynn RP, Kwok J, Klausner JD. Acceptability of using electronic vending machines to deliver oral rapid HIV self-testing kits: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]