Abstract

The current longitudinal study examined how Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ (N = 204) reports of acculturative stress during late adolescence were associated with their educational attainment and engagement in risky behaviors in young adulthood, 4 years post-partum; we also examined whether this association was mediated by discrepancies between adolescents’ educational aspirations and expectations. Findings revealed that mothers’ greater reports of stress regarding English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate were associated with a larger gap between their aspirations and expectations. Mothers’ reports of greater stress from pressures against assimilation, however, were associated with a smaller gap between aspirations and expectations. As expected, a larger gap between aspirations and expectations was associated with lower educational attainment and increased engagement in risky behaviors. Finally, significant mediation emerged, suggesting that the influence of stress from English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate on young mothers’ educational attainment and engagement in risky behaviors was mediated through the aspiration–expectation gap. Findings are discussed with respect to understanding discrepancies between young mothers’ aspirations and expectations in the context of acculturative stress.

Keywords: Acculturative stress, Educational aspirations, Educational expectations

1. Risky behaviors and educational attainment among young Mexican-origin mothers: the role of acculturative stress and the educational aspiration–expectation gap

Latinos are the largest ethnic population in the United States (U.S.), and the Latino population is among the fastest growing ethnic groups in the nation (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Despite the growing presence of Latinos in U.S. schools, Mexican-origin youth experience the highest dropout rates of all racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. (23.2%), followed by American Indian/Alaska Native (17.6%) and Black (12.9%) youth (U.S. Department of Education, 2012), and consequently a lower likelihood of earning a bachelor’s degree, compared to their higher-performing non-Latino White and Asian immigrant counterparts (Fry, 2010). Further, Latino youth also have high rates of engagement in risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex, smoking, alcohol abuse, physical fighting) compared to non-Latino youth (Kann et al., 2014). In particular, Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, who have the highest birthrates in the U.S. among all racial/ethnic groups (National Vital Statistics Report, 2013), are at significant risk for experiencing educational underachievement (Motel & Patten, 2012) and engagement in risky behaviors (Assini-Meytin & Green, 2015; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2009) due, in part, to low income (Hoffman, 2006), social stratification in school systems (Lamb & Markussen, 2011), and high rates of school dropout (Rumberger, 2011). Given that these indices of adjustment have been linked to employment earnings, health behaviors, and offspring’s developmental outcomes (Borkowski, Whitman, & Farris, 2007), a comprehensive understanding of factors that inform young mothers’ educational attainment and engagement in risky behavior is warranted.

In the current study, we hypothesize that disparities in educational and behavioral adjustment among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers may be attributed to unique cultural stressors faced by Latino youth as a result of the pressures associated with the acculturation process (e.g., language difficulties, discrimination, differing cultural values; Rodriguez, Myers, Morris, & Cardoza, 2000). Prior work with Latino youth has found that acculturative stress, or stressors experienced by immigrant groups during the process of adapting to a dominant culture (Berry, 2006), are associated with poor school performance (Roche & Kuperminc, 2012) and engagement in risky behaviors (Forster, Grigsby, Soto, Schwartz, & Unger 2015; Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000). Despite the growing representation of Latino immigrants in the U.S. and teen mothers’ high risk for poor adjustment, limited work has examined the role of distinct aspects of acculturative stress (e.g., English/Spanish competency pressures, pressures to or against assimilation), as well as the process through which acculturative stress may inform educational and behavioral adjustment. The current study contributes to the scant literature underscoring the role of multidimensional aspects of acculturative stress on youths’ adjustment, particularly among at-risk underrepresented groups, such as Mexican-origin teen mothers.

Acculturative stress may ultimately contribute to young mothers’ educational and behavioral adjustment by impacting the formation of their self-concept, educational goals, and resultant behaviors via perceptions of limited resources (e.g., financial constraints; Lueck & Wilson, 2011). Prior work suggests that challenges associated with the stress of adaptation to cultural expectations may lower immigrant youths’ hopes or aspirations for future educational attainment (Plunkett & Bámaca-Gómez, 2003; Yowell, 2002). A concept closely related to educational aspirations is the concept of educational expectations (i.e., realistic self-estimates for educational attainment; Reynolds & Pemberton, 2001), which has been regarded as equally critical to achievement and developmental adjustment (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Research suggests that when youth aspire to achieve more than they actually expect to achieve (i.e., larger aspiration–expectation gap), they are more inclined toward disengagement from school and behavioral issues (Boxer, Goldstein, DeLorenzo, Savoy, & Mercado, 2011), compared to those with a smaller aspiration–expectation gap. This notion has been termed academic disidentification (Steele, 1997), and refers to the act of devaluing or psychologically disengaging (e.g., lowering aspirations, expectations) from schooling domains, leading to academic underachievement and delinquent behavior (Griffin, 2002). Academic disidentification has been recognized as a protective mechanism used by individuals during psychologically threatening situations (e.g., experiences with acculturative stress). Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, who experience social stigmas both as young mothers (SmithBattle, 1995) and as members of an ethnic minority group (Rodriguez et al., 2000), may be particularly vulnerable to academic disidentification. The discrepancy between aspirations and expectations may be a byproduct of internalized social disadvantages, such that young Mexican-origin mothers who experience the pressures of acculturative stress may have difficulty matching their aspired selves with their expected selves, which ultimately impedes their educational attainment and places them at risk for engagement in risky behaviors.

Researchers propose that gaps between ethnic minority youths’ educational aspirations and expectations may be attributed to incongruence between their ideological perceptions of the U.S. American Dream alongside greater barriers (e.g., child rearing responsibilities) to fulfilling those dreams (Yowell, 2002). Similarly, pressures associated with the assimilation process may elicit feelings of limited resources, which decrease young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational self-concept (e.g., internalized beliefs regarding academic capabilities), and consequently increase the gap between their educational aspirations and expectations. Limited work, however, has investigated the impact of specific cultural stressors on the gap between ethnic minority youths’ educational aspirations and expectations. This process may be particularly salient for Mexican-origin adolescent mothers in the years following their pregnancy and in young adulthood, a critical developmental period marking the beginning of social maturity and new opportunities for educational investment (i.e., obtaining higher education). Guided by possible selves (Oyserman & Fryberg, 2006) and acculturative stress perspectives (Berry, 2006), the current study examined the impact of young Mexican-origin mothers’ reports of acculturative stress in relation to discrepancies between their educational aspirations and expectations, and how these stressors and discrepancies informed their adjustment (i.e., educational attainment and risky behavior engagement) over time.

2. Acculturative stress and young Mexican-origin mothers’ adjustment

Acculturative stress can be understood as individuals’ responses to the pressures associated with events surrounding interactions between cultures throughout the process of acculturation (Berry, 2006). These stressors include feelings of being marginalized due to cultural differences (Mena, Padilla, & Maldonado, 1987), and may derive from both the dominant or heritage culture, and entail pressures to retain and/or reject aspects of the dominant and heritage culture (e.g., English/Spanish competency pressures, pressures to assimilate, pressures against assimilation; Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002). Within the literature on acculturation, individuals’ engagement in negotiations over assuming host-culture practices, values, and identifications and disregarding those from the heritage culture (i.e., the focus of the present study) are referred to as assimilation pressures (Berry, 2006; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez, & Wang, 2007). Empirical findings with Latino youth suggest that acculturative stress, in general, impacts youths’ educational adjustment (e.g., school performance; Roche & Kuperminc, 2012) and engagement in risky behavior (e.g., substance abuse; Gil et al., 2000). Relatively few studies, however, have examined how unique aspects of acculturative stress differentially impact Latino youths’ adjustment (Rodriguez et al., 2002).

In one cross-sectional study with Latino middle school students, Roche and Kuperminc (2012) found that discrimination stress (e.g., stress from perceived stereotypes against Latinos) impacted youths’ school performance through school belonging, such that when youth reported greater discrimination stress, they were also more likely to report lower school belonging, which in turn predicted youths’ lower grades. This association, however, was not found with immigration-related stress (e.g., stress associated with perceiving distance from the heritage country), suggesting that specific types of acculturative stress may differentially impact youths’ educational adjustment. Interestingly, similar distinctions have emerged in work with Mexican-origin adults (i.e., Rodriguez et al., 2002).

Similarly, studies of immigrant youth and young adults have documented links between acculturative stress and engagement in risky behaviors. In particular, prior findings indicate that greater experiences with acculturation related pressures (e.g., discrimination, social norms, language competencies) may be associated with higher levels of risky behavior engagement (e.g., alcohol and substance abuse, aggression, rule breaking) among immigrant minority adolescents and young adults (e.g., Latino, Asian; Forster et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2000; Kam, 2011; Thai, Connell, & Tebes, 2010). In a study with recently immigrated Hispanic youth, researchers found that higher levels of acculturation-related stress (e.g., embarrassment about having an accent or not speaking English well) were positively associated with deviant behaviors (i.e., aggression, rule breaking behavior; Forster et al., 2015). Scholars have offered that immigrant youth who encounter acculturative stressors from the heritage or host country may engage in risky behavior to challenge family authority and promote peer acceptance (Gil & Vega, 1996; Thai et al., 2010). Despite these findings, relatively limited work has examined the role of multidimensional aspects of acculturative stress on youths’ engagement in risky behavior, particularly among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers.

Multidimensional conceptualizations of acculturative stress take into account the pressures associated with the experiences of adopting and negotiating U.S. American and Latino lifestyles (Rodriguez et al., 2002). Acculturative stress may encompass tensions surrounding the maintenance of one’s heritage culture (i.e., enculturation) while adopting the practices of the new host culture (i.e., acculturation). The pressures associated with acculturative stress can be distinguished as enculturative and acculturative pressures. Enculturative pressures entail pressures to retain aspects of the heritage culture and pressures to reject aspects of the dominant culture (i.e., Spanish competency pressures, pressures against assimilation). Conversely, acculturative pressures refer to pressures to adapt to the practices and beliefs of the dominant culture (i.e., English competency pressures, pressures to assimilate).

Despite research findings suggesting that Latino youth indeed experience acculturative stress (Gonzales, Fabrett, & Knight, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Alfaro, 2009), and evidence supporting the direct link between acculturative stress and educational (Plunkett & Bámaca-Gómez, 2003; Roche & Kuperminc, 2012) and behavioral maladjustment (Forster et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2000; Kam, 2011; Thai et al., 2010), the mechanism through which specific dimensions of acculturative stress impact individuals’ adjustment is not well understood. Some research suggests that acculturative stress may prompt emerging adults’ maladjustment through increased hopelessness. In a longitudinal study with an ethnically diverse sample (i.e., Asian, White, Latino, Black) of emerging adults from a diverse public college, Polanco-Roman and Miranda (2013) found that acculturative stress positively predicted youths’ depression through hopelessness (e.g., expectations, loss of motivation, feelings about the future). Although hopelessness encompassed a broad array of negative sentiment among diverse college populations, findings indicated that one mechanism by which acculturative stress may have informed youths’ adjustment was via decreased expectations for a positive future. Considered in tandem with previous findings suggesting that challenges during the acculturation process may decrease minority youths’ educational aspirations, or beliefs about how far they will go in school (Yowell, 2002), it is possible that specific pressures associated with acculturative stress may uniquely inform young mothers’ educational and behavioral adjustment through the development of mismatched aspirations and expectations.

3. Mediating role of the aspiration–expectation gap

High educational aspirations and expectations have been linked to numerous positive outcomes, including greater academic motivation, higher levels of educational attainment, more prestigious occupational achievement, and lower engagement in risky behavior (e.g., delinquent involvement, substance abuse; Beal & Crockett, 2010; Mellow, 2008; Messersmith & Schulenberg, 2008; Oyserman & Fryberg, 2006). Research on youths’ educational aspirations and expectations suggests that when youths’ educational desires or aspirations are more closely matched to their educational expectations (i.e., smaller aspiration–expectation gap), youth are more likely to persist in completing their educational goals (Oyserman, Brickman, & Rhodes, 2007) and avoid engagement in risky behavior that would impede them from completing their goals (Boxer et al., 2011; Oyserman & Fryberg, 2006). A larger gap between youths’ aspirations and expectations, however, has been associated with lower subsequent educational attainment and greater engagement in risky behavior (Boxer et al., 2011).

Possible selves’ perspectives hold that individuals’ perceptions about their future selves, in part, dictate their present behavioral choices and decisions (Nurmi, 2004). These possible selves are manifestations of personalized representations of future selves that are informed by a combination of individuals’ desires and expectations for themselves in a future situation as well as by social processes (e.g., socioeconomic status; Erikson, 2007). A match between individuals’ aspirations and expectations reflect more salient possible selves, which may bridge cognitive self-representations (i.e., possible selves) with the motivation to actualize their possible selves. Accordingly, gaps between young mothers’ educational aspirations and expectations may make it difficult for them to feel motivated to engage in strategies necessary to fulfill their educational goals and expected behaviors (e.g., prioritize childrearing responsibilities over time spent with peers). Mexican-origin teen mothers may be particularly susceptible to experiencing gaps between their aspirations and expectations, given research suggesting that teen mothers are at risk for encountering additional barriers (e.g., necessity to work) and limited school resources (e.g., childcare centers) necessary to continue their education (Hoffman, 2006; Leadbeater & Way, 2001); this, in turn, may lower perceived realistic self-estimates, or educational expectations (Bravo, Toomey, Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Jahromi, in press; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002), as teen mothers enter young adulthood, and increase the gap between aspirations and expectations regarding educational attainment.

Given previous work identifying a larger gap between youths’ educational aspirations and expectations as problematic, researchers have highlighted the importance of understanding factors that inform this gap (Boxer et al., 2011; Kirk et al., 2012). This knowledge is particularly important for young Mexican-origin mothers, as prior research highlights Latino youths’ and teen mothers’ propensity toward educational underachievement (Pew Hispanic Center, 2008; Hoffman, 2006) and engagement in risky behaviors (e.g., smoking, substance abuse, delinquent behavior; Assini-Meytin & Green, 2015). Gaps between youths’ aspirations and expectations have been attributed to various disparities (e.g., poverty, low parental education; Perry, Przybysz, & Al-Sheikh, 2009), and are more common among ethnic minority youth (e.g., Latino, African American; Kirk et al., 2012; Messersmith & Schulenberg, 2008), particularly those who are teen mothers (Barr & Simons, 2012; Hellenga, Aber, & Rhodes, 2002). These disparities may be explained by the unique cultural stressors experienced by ethnic minority youth, such as those related to the acculturation process.

Although associations between specific indicators of acculturative stress and young Mexican-origin mothers’ aspiration–expectation gap have not been examined in prior research, language use (e.g., proficiency, brokering) has emerged as a significant predictor of Mexican-origin youths’ behavioral and emotional adjustment (Kam, 2011). Importantly, prior work with immigrant populations (i.e., Asian, Latino) suggests that language proficiency, from both the heritage and host country, is a strong indicator of acculturative stress and cultural adaptation (Lueck & Wilson, 2010; Lueck & Wilson, 2011). Scholars have offered that pressures stemming from language proficiencies may drive Latinos’ perceptions of their own social positions in the host country and prospectively guide social interactions (Lueck & Wilson, 2011). For instance, individuals with limited language proficiency in English, may experience pressures to speak English (i.e., acculturative pressures), and encounter distance between themselves and their English-speaking peers (e.g., classmates, teachers; Tabors, 1997), making it difficult to believe or expect they are capable of accomplishing their aspired selves with respect to education.

Likewise, Spanish competency pressures (i.e., enculturative pressures) may also negatively impact youths’ aspired or realistic educational goals for themselves, as prior research suggests that maintaining Spanish during the process of acculturation is important for promoting Latinos’ mental health (Kam, 2011; Zhang, Hong, Takeuchi, & Mossakowski, 2012). Researchers pose that maintaining Spanish language use may signify closer relationships and greater support from individuals’ families or cultural community members. Furthermore, some research indicates that failure to maintain Spanish language use may be associated with greater pressures to improve Spanish-speaking skills in an effort to maintain a heritage or Hispanic identity (Schwartz et al., 2007). Thus, young mothers’ experiences with Spanish competency pressures may reduce their perception of cultural resources, and lead to lower expectations for educational attainment.

Other acculturative stressors, such as the pressures to assimilate or pressures against assimilation may similarly decrease young mothers’ educational self-concept, as these pressures may underscore conflicting value systems (Mena et al., 1987). Conflicts among individuals’ value systems may generate feelings of disconnect from the mainstream or heritage culture, especially within a school or educational setting (Roche & Kuperminc, 2012), making it challenging for young Mexican-origin mothers to gain access to resources (e.g., tutoring, family support) that would enable them to achieve academically, and thus lowering their educational expectations for themselves. Similarly, a disconnect from U.S. American or Latino culture may lower incentives for young mothers to avoid engagement in risky behaviors, as these young mothers may disidentify with social norms and cultural expectancies for young mothers that prioritize familial responsibilities.

Acculturative stress may negatively impact young mothers’ educational self-concept by eliciting feelings of lower academic abilities, limited environmental support, lack of belongingness, and a lack of control, thus increasing the gap between their educational aspirations and expectations, and consequently negatively impacting their educational and behavioral adjustment. Consistent with possible selves perspectives (Cross & Markus, 1994), young mothers’ self-concept, informed by acculturative stress, may negatively impact their educational expectations (i.e., larger aspiration–expectation gap), as Latino youths’ and adolescent mothers’ motivation to achieve is derived from their self-concept (Erikson, 2007; Barr & Simons, 2012). Thus, there is conceptual work that supports the notion that each aspect of acculturative stress should positively predict a larger educational aspiration–expectation gap. To our knowledge, however, no studies have simultaneously examined multiple acculturative stressors as unique predictors of young Mexican-origin mothers’ academic and behavioral adjustment; the current study will provide new empirical evidence in this regard.

Using a longitudinal design, we hypothesized that higher levels of indicators of acculturative stress (i.e., Spanish/English competency pressures, pressure to/against assimilation) would be associated with a larger aspiration–expectation gap; a larger aspiration–expectation gap, in turn, was expected to be associated with greater engagement in risky behaviors and lower educational attainment. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the discrepancy between young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational aspirations and expectations (i.e., aspiration–expectation gap) during late adolescence would mediate the association between specific indicators of acculturative stress and their educational and behavioral adjustment during young adulthood.

4. Method

4.1. Participants

Data were from an ongoing longitudinal study of Mexican-origin teen mothers (N = 204), their infants, and their mother figures (Umaña-Taylor, Guimond, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2013). Pregnant adolescents initially participated in semi-structured and face-to-face interviews during their third trimester of pregnancy (Wave 1; W1) and every year thereafter for five years. Data used in the current study were from two years post-partum (Wave 3; W3) to four years post-partum (Wave 5; W5), as this is a critical developmental period marked by challenges related to balancing childrearing responsibilities and educational pursuits (Barr & Simons, 2012). Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Full sample (N =200)

|

U.S. born (n = 130)

|

Mexico born (n = 70)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | M (SD) | Range | % | M (SD) | Range | % | M (SD) | Range | |

| Nativity demographics (n = 200)a |

|||||||||

| W1 U.S. born | 65% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| W1 Mexico born | 35% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| W1 length of time in U.S. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7.8 (4.7) | 0–18 years |

| Educational demographics | |||||||||

| W1 (n = 200) | |||||||||

| W1 enrolled in school | 58% | – | – | 62% | – | – | 50% | – | – |

| W1 GED/high school | 5% | – | – | 4% | – | – | 7% | – | – |

| W1 dropout | 37% | – | – | 34% | – | – | 43% | – | – |

| W2 (n = 190) | |||||||||

| W2 enrolled in school | 40% | – | – | 44% | – | – | 34% | – | – |

| W2 GED/high school | 17% | – | – | 17% | – | – | 18% | – | – |

| W2 dropout | 43% | – | – | 39% | – | – | 48% | – | – |

| W3 (n = 170) | |||||||||

| W3 enrolled in school | 29% | – | – | 36% | – | – | 17% | – | – |

| W3 GED/high school | 29% | – | – | 30% | – | – | 26% | – | – |

| W3 dropout | 42% | – | – | 34% | – | – | 57% | – | – |

| W4 (n = 167) | |||||||||

| W4 enrolled in school | 21% | – | – | 27% | – | – | 10% | – | – |

| W4 GED/high school | 41% | – | – | 40% | – | – | 44% | – | – |

| W4 dropout | 38% | – | – | 33% | – | – | 46% | – | – |

| W5 (n = 169) | |||||||||

| W5 enrolled in school | 13% | – | – | 18% | – | – | 3% | – | – |

| W5 GED/high school | 46% | – | – | 46% | – | – | 44% | – | – |

| W5 dropout | 41% | – | – | 36% | – | – | 53% | – | – |

| W3 employment status (n = 170) | |||||||||

| Not working for pay | 53% | – | – | 52% | – | – | 59% | – | – |

| <40 hours per week | 30% | – | – | 34% | – | – | 21% | – | – |

| 40 hours or more per week | 17% | – | – | 14% | – | – | 20% | – | – |

| W3 household information | |||||||||

| Household income (n = 143) | – | $24,283 ($19,025) | $315–$122,000 | – | $27,480 ($20,677) | $315–$122,000 | – | $17,090 ($12,016) | $600–$48,000 |

| Numberof people in home (n = 170) | – | 5 (2.5) | 1–17 | – | 5 (2.5) | 1–13 | – | 5 (2.5) | 2–17 |

| Mother coresidency (n = 174) | 53% | – | – | 54% | – | – | 50% | – | – |

| Dating partner coresidency (n = 170) | 30% | – | – | 29% | – | – | 30% | – | – |

| Mother and dating partner coresidency (n = 170) | 11% | – | – | 11% | – | – | 10% | – | – |

Note: W1 = Wave 1, W3 = Wave 3, W4 = Wave 4, W5 = Wave 5.

Sample presented here reflects the omission of 4 outliers whose education expectations exceeded their aspirations.

4.2. Procedure

Pregnant adolescents were recruited from high schools, health centers, and community agencies in a large Southwestern metropolitan area. To participate in the study, participants had to be 15 to 18 years old, in their third-trimester of pregnancy, of Mexican descent, not legally married, and have a mother figure who was also willing to participate. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained for participants younger than 18 years, and informed consent was obtained for those who were 18 years and older, in compliance with the Arizona State University Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Of the 204 adolescents who participated at W1, 85% participated at W3, 84% participated at W4 (i.e., Wave 4), and 85% participated at W5. Attrition analyses (i.e., t-tests, chi-square tests) revealed that there were no significant differences between participants who completed all study waves, compared to those who did not, on demographic or key study variables (i.e., Spanish/English competency pressures, pressures to/against assimilation, aspiration–expectation gap, risky behaviors, educational attainment) assessed at W1.

Adolescents completed semi-structured and face-to-face interviews (averaging approximately 2.5 h in length), in which all questions were read aloud by an interviewer, when the adolescent mother was approximately 24-months postpartum (W3), 36-months postpartum (W4), and 48-months postpartum (W5). Participants received $35, $40, and $50 for participation at W3, W4, and W5, respectively. Interviews were conducted in the participants’ preferred language (i.e., English or Spanish), with 65% of young mothers completing their interviews in English at W3.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Demographic controls

Demographic controls included young mothers’ nativity, age, economic hardship, and school enrollment at W3. Young mothers’ nativity was coded as 0 (born in Mexico) or 1 (born in the U.S.), based on their reports at W1. School enrollment was coded as 0 (dropped out) or 1 (currently attending school). Young mothers’ economic hardship at W3 was assessed using a 20-item measure (Barrera, Caples, & Tein, 2001), which included four subscales to assess economic hardship: financial strain (2 items; e.g., “In the next three months, how often do you think that you or your family will experience bad times such as poor housing or not having enough food?” with endpoints of [1] almost never and [5] almost always); inability to make ends meet (3 items; e.g., “In the last three months, my/our expenses always exceed our income,” with endpoints of [1] strongly disagree and [5] strongly agree); not enough money for necessities (4 items; e.g., “We had enough money to afford the kind of car we needed,” with endpoints of [1] strongly disagree and [5] strongly agree); economic adjustments or cutbacks (9 items; e.g., “In the last 3 months, has your family had to change food shopping or eating habits a lot to save money?” with responses coded as either [1] yes or [2] no). Responses were weighted to create a composite score (see Barrera et al., 2001), with higher scores indicating greater economic hardship. Cronbach’s alpha, computed using the unweighted standardized economic hardship subscale scores, was .80.

4.3.2. Acculturative stress

Young mothers’ reports of acculturative stress were assessed at W3 using the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (Rodriguez et al., 2002). This measure is composed of 25 items capturing four types of acculturative stress: Spanish competency pressures (e.g., “I have a hard time understanding others when they speak Spanish”), English competency pressures (e.g., “It bothers me that I speak English with an accent”), Pressure to acculturate (e.g., “It bothers me when people pressure me to assimilate to the American ways of doing things”), and Pressure against acculturation (e.g., “People look down upon me if I practice American customs”). The current study uses the terminology Pressure to/against assimilation for the latter two scales, rather than Pressure to/against acculturation. This modification in terminology was made to coincide with the tradition of acculturation research in which assimilation pressures refer to negotiations over adopting host-culture practices, values, and identifications and discarding those from the heritage culture (Berry, 2006; Schwartz et al., 2007). Participants indicated whether or not an event had occurred in the past 3 months. If the event had not occurred, participants received a score of 0. If the event had occurred, participants reported how stressful the event was using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not at all stressful (1) to extremely stressful (5). Higher scores indicated higher levels of acculturative stress for each of the four dimensions. Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales were as follows: Spanish competency pressures (α = .92), English competency pressures (α = .92), pressure to assimilate (α = .83), and pressure against assimilation (α = .71). A confirmatory factor analysis was examined with four latent constructs (one for each subscale) and indicated acceptable model fit, χ2 (df = 262) = 533.913, p < .001; CFI = .90; RMSEA = 0.08 (90% C.I.: .07–.09); SRMR = .08. Furthermore, findings indicated that each item loaded significantly onto its respective acculturative stress subscale factor (all p values < .05).

4.3.3. Aspiration–expectation gap

Young mothers were asked about their educational aspirations at all waves with the following question: “How far would you like to go in school?” Similarly, expectations were assessed with the question: “How far do you really think you will go in school?” Responses were coded to reflect the number of years of schooling (e.g., 10 = 10th grade; 16 = bachelor’s degree; 20 = doctorate or professional degree). Using W4 data for these questions, a difference score was created to assess the gap between young mothers’ aspirations and expectations; specifically, mothers’ reports of educational expectations were subtracted from their aspirations (Range = 0–11; M = .70, SD = 1.61). Those whose expectations were greater than their aspirations (n = 4) were considered outliers and excluded from further analyses, as empirical work on aspiration–expectation discrepancies has generally found that aspirations (i.e., hopes for educational attainment) are greater than expectations (i.e., realistic self-estimates for educational attainment; Boxer et al., 2011). This resulted in an analytic sample of n = 200.

4.3.4. Educational attainment

Young mothers’ educational attainment was self-reported at W5 via one item: “How much schooling have you completed?” The same response scale that was used to code educational expectations, described above, was employed. The range for young mothers’ educational attainment at W5 was 7th grade to 2 years of postsecondary education (M = 11.29, SD = 1.51).

4.3.5. Risky behaviors

Young mothers’ engagement in risky behaviors was assessed at W4 and W5 using a 24-item measure (Eccles & Barber, 1990). Participants indicated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to more than 10 times (4), how many times they engaged in a risky behavior (e.g., done something you knew was dangerous just for the thrill of it; gotten drunk or high; stole something worth $50 or more; started a fight with someone) during the past year. This scale has demonstrated good reliability with Mexican American adolescents (α = .92; Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Crouter, 2006). Previous research with the current sample has demonstrated support for the reliability and validity of this measure with teen mothers (Toomey, Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2015). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas for young mothers were .90 at W4 and .90 at W5.

5. Results

5.1. Analytic strategy

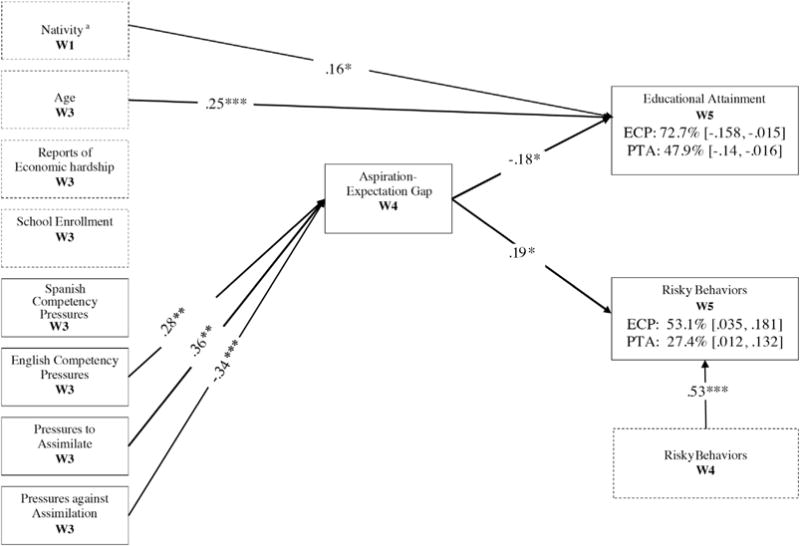

Path analysis within a structural equation modeling framework in Mplus version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) was used to examine how young mothers’ reports of acculturative stress at W3 (i.e., Spanish competency pressures, English competency pressures, pressure to assimilate, pressure against assimilation) informed the aspiration–expectation gap at W4 and, in turn, W5 educational attainment and engagement in risky behaviors among teen mothers (see Fig. 1). Because teen mothers’ educational expectations have been shown to decrease post-partum (Barr & Simons, 2012), hypotheses were tested two years post-partum, in an effort to examine associations among study variables after mothers had transitioned through their first year of parenting.

Fig. 1.

Model of predictors and outcomes related to the aspiration–expectation gap. Model fit indices: CFI = 0.99, χ2 (2) = 3.11, p = .21, RMSEA = .05 (.00–.16), SRMR = .02.

Note: Only significant paths are shown. Covariates are represented by dashed boxes. Bolded paths indicate significant mediation. Percentages signify the proportion mediated by the aspiration–expectation gap. 95% confidence interval for the mediated effect represented by brackets. W1 = Wave 1; W3 = Wave 3; W4 = Wave 4; W5 = Wave 5. a0 = Mexico-born, 1 = U.S.-born. *p < .05. **p < .01, ***p < .001. Sample presented here reflects the omission of 4 outliers whose education expectations exceeded their aspirations.

Several control variables were included in the model. Because prior work suggests that the effects of acculturative stress (Yowell, 2002) and the formation of educational goals (Oyserman & Fryberg, 2006) may differ based on youths’ country of origin, we controlled for nativity. Young mothers’ reports of economic hardship were included as a control, given that youth from economically disadvantaged backgrounds have demonstrated relatively larger gaps between their educational aspirations and expectations (Boxer et al., 2011). Next, given literature highlighting the link between teen mothers’ dropout status and educational aspirations and expectations (Rumberger, 2011), such that youth who dropout are more likely to lower expectations for future attainment, we controlled for young mothers’ school enrollment status. Additionally, we controlled for young mothers’ age, given that educational attainment has been positively associated with age and prior work has noted that discrepancies between aspirations and expectations may increase with age (Kirk et al., 2012). Lastly, we controlled for young mothers’ reports of prior engagement in risky behavior, assessed at W4, to provide a more rigorous test of our hypotheses.

All exogenous variables were allowed to covary (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). To account for missing data, we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML; Arbuckle, 1996), which uses all available information from observed data to provide likelihood estimates of missing data. The proportion of missing data ranged from 15% to 20% across all study variables. Good (acceptable) model fit was determined based on fit indices with a value of greater than or equal to 0.95 (greater than or equal to 0.90) for the comparative fit index (CFI), and less than or equal to 0.05 (.08) for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2016).

5.2. Descriptive results

All descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among study variables were conducted using data estimated via FIML; means and standard deviations for study variables were calculated in Mplus with uncentered variables (see Table 2). Examination of these descriptive statistics indicated that young mothers’ nativity status was positively associated with stress associated Spanish competency pressures, such that U.S.-born mothers reported higher stress associated with pressures to speak and understand Spanish compared to Mexico-born mothers. English competency pressures and pressure to assimilate were negatively associated with nativity status, indicating that Mexico-born mothers experienced higher levels of stress associated with pressures to assimilate and speak and understand English, compared to U.S.-born mothers. Stress associated with pressures to assimilate were negatively associated with school enrollment, such that mothers who reported greater stress resulting from pressures to assimilate were more likely to drop out of school. Stress associated with English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate were positively associated with the aspiration–expectation gap. Educational attainment was positively associated with stress related to Spanish competency pressures, and negatively associated with stress associated with English competency pressures, pressures to assimilate, and pressures against assimilation.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables (n = 200).

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.W1 nativitya | – | |||||||||||

| 2. W3 economic hardshipb | −.19** | – | ||||||||||

| 3. W3 age | .07 | −.07 | – | |||||||||

| 4. W3 school enrollmentc | .02 | −.01 | .03 | – | ||||||||

| 5. W3 Spanish competency pressures | .34*** | −.01 | −.03 | .10 | – | |||||||

| 6. W3 English competency pressures | −.27*** | .44*** | −.03 | −.09 | −.13* | – | ||||||

| 7. W3 pressures to assimilate | −.16* | .26*** | −.01 | −.18** | .03 | .53*** | – | |||||

| 8. W3 pressures against assimilation | .04 | .22*** | −.10 | −.01 | .29*** | .30*** | .59*** | – | ||||

| 9. W4 aspiration-expectation gapd | −.09 | .10 | −.04 | −.02 | −.07 | .37*** | .27*** | .03 | – | |||

| 10. W4 risky behaviors | .14* | .26*** | −.05 | −.10 | .16* | .07 | .10 | .19** | .10 | – | ||

| 11.W5 riskybehaviors | .10 | .23*** | .01 | −.02 | .17** | .04 | .19** | .21** | .20** | .58*** | – | |

| 12. W5 educational attainment | .24*** | −.16* | .29*** | .10 | .13* | −.24*** | −.26*** | −.21*** | −.23*** | −.08 | −.14* | – |

| Mean | .65 | −.02 | 18.92 | .40 | .77 | .43 | .75 | .46 | .70 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 11.29 |

| SD | .48 | 2.36 | 1.00 | .49 | .99 | .82 | .80 | .64 | 1.61 | .30 | .27 | 1.51 |

Note: Sample presented here reflects the omission of 4 outliers whose education expectations exceeded their aspirations.

W1 = Wave 1, W3 = Wave 3, W4 = Wave 4, W5 = Wave 5. Sample Items: Spanish competency pressures (e.g., “I have a hard time understanding others when they speak Spanish”); English competency pressures (e.g., “I have a hard time understanding others when they speak English”); pressure to assimilate (e.g., “People look down upon me if I practice Mexican/Latino customs”); pressure against assimilation (e.g., “People look down upon me if I practice American customs”).

0 = Mexico-born, 1 = U.S.-born.

Economic hardship was coded so that higher values indicate more economic hardship.

0 = Dropped out, 1 = Currently attending school.

The aspiration–expectation gap was computed by subtracting mothers’ educational expectations from their aspirations (Range = 0–11).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Regarding the manner in which acculturative stress subscales correlate with one another in the current sample, results are consistent with findings presented by Rodriguez et al. (2002) using the same measure. In both studies, correlations indicated that pressures to assimilate and pressures against assimilation (termed pressures to/against acculturation in Rodriguez et al., 2002) were positively and significantly correlated, suggesting that individuals with bicultural ties may experience similarly high levels of acculturative stress from both the heritage and host culture. Next, those participants who reported the greatest stress from pressures to become competent in the Spanish language also experienced greater pressures against assimilation, suggesting that those who are more assimilated experience stress regarding engagement with the culture of origin. Moreover, stress from English competency pressures were positively correlated with both pressures to and against assimilation, suggesting that less assimilated adolescents experienced simultaneous stress associated with pressures from mainstream U.S. America and from the heritage culture.

With respect to the gap between young mothers’ educational aspirations and expectations, findings indicated that a majority of mothers (n = 127) reported aspirations that matched their expectations, as indicated by a difference score of 0. Moreover, descriptive statistics indicated that the gap decreased over time as follows: 3rd trimester of pregnancy (M = 1.2, SD = 2.02, Range = 0–12), 1 year post-partum (M = .99, SD = 1.45, Range = 0–6), 2 years post-partum (M = .86, SD = 1.65, Range = 0–8), 3 years post-partum (M = .71, SD = 1.63, Range = 0–11), and 4 years post-partum (M = .62, SD = 1.34, Range = 0–7). This decrease in discrepancies over time is consistent with prior literature suggesting that educational expectations become adjusted over time to more closely resemble aspirations due to increased life experiences and perceptions of attainable goals (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002).

5.3. Test of the hypothesized model

Fit indices suggested good fit for the hypothesized model: χ2 (df = 2) = 3.11, p = .21; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = .05 (90% C.I.:.00–.16); SRMR = .02. With respect to controls, age (b = .25, p < .001, 95% CI: .02–.13) and nativity status (b = .16, p = .04, 95% CI: .01–.31) had a direct effect on young mothers’ educational attainment. Hypotheses regarding associations between indicators of acculturative stress and the aspiration–expectation gap were partially supported. As expected, there was a statistically significant effect of stressors associated with English competency pressures (b = .28, p = .003, 95% CI: .09–.46) and pressure to assimilate (b = .36, p = .001, 95% CI: .15–.56) on the aspiration–expectation gap, such that young mothers’ reports of higher stress were associated with a larger gap between aspirations and expectations. Young mothers’ reports of greater stress regarding pressures against assimilation (b = −.34, p < .001, 95% CI: .53–−.15), however, were associated with a smaller gap between aspirations and expectations. The relation between stress associated with Spanish competency pressures and the aspiration–expectation gap was not significant (b = .02, p = .81, 95% CI: −.02–.28).

As expected, the relation between the aspiration–expectation gap and educational attainment was statistically significant (b = −.18, p = .03, 95% CI: .06–.23), such that a larger gap between aspirations and expectations was associated with lower educational attainment, after accounting for indicators of acculturative stress, young mothers’ nativity, age, and economic hardship. Similarly, the relation between the aspiration–expectation gap and risky behaviors was statistically significant (b = .19, p = .01, 95% CI: .04–.35), such that a larger gap was associated with increases in engagement in risky behaviors, after accounting for acculturative stress, young mothers’ nativity, age, economic hardship, and the prior year’s reports of engagement in risk behaviors.

5.4. Test of mediation

Mediation was tested using the bias-corrected bootstrap method to compute confidence intervals for the mediated effects (Mackinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). The bias-corrected bootstrap method suggests that mediation is significant if the confidence interval does not contain zero. The current study used the standard of 2000 bootstrap samples, and mediation tests indicated that stress associated with English competency pressures (95% confidence interval for the mediated effect = −.16, −.02) and pressure to assimilate (95% confidence interval for the mediated effect = −.14, −.02) each indirectly predicted educational attainment via the aspiration–expectation gap. Stress associated with English competency pressures (95% confidence interval for the mediated effect = .035, .181) and pressure to assimilate (95% confidence interval for the mediated effect = .012, .132) also each indirectly predicted engagement in risky behaviors via the aspiration–expectation gap. With respect to the proportion of effect mediated for stress associated with English competency pressures, 72.7% of the total effect of English competency pressures on educational attainment was mediated through the aspiration–expectation gap, and 53.1% of the total effect of stress from English competency pressures on risky behaviors was mediated through the aspiration–expectation gap. For pressure to assimilate, the aspiration–expectation gap mediated 47.9% and 27.4% of the total effect of stress resulting from pressures to assimilate on educational attainment and risky behaviors, respectively. Finally, the adjusted direct effects on educational attainment and risky behaviors were not significant for stress resulting from English competency pressures (ĉ′ = −.02, p = .83, 95% CI: .00–.12; ĉ′ = −.17, p = .07, 95% CI: −.01–.11) or pressure to assimilate (ĉ = −.06, p = .59, 95% CI: −.14–.23; ĉ′ = .15, p = .14, 95% CI: −.12–.32). There was no significant mediation between stress related to pressures against assimilation and either outcome (i.e., educational attainment and risky behaviors) via the aspiration–expectation gap.

6. Discussion

Research with Latinos highlights the adverse role of acculturative stress (i.e., tensions that individuals from immigrant groups experience during the process of acculturating to a dominant culture; Berry, 2006) on educational and behavioral adjustment (Forster et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2000; Kam, 2011; Oyserman et al., 2007; Roche & Kuperminc, 2012). Limited work, however, has examined the mechanisms through which acculturative stress impacts adjustment among at-risk Latinos, such as Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Furthermore, relatively few studies have taken into account the multidimensional nature of acculturative stress on Latinos’ adjustment (Rodriguez et al., 2002).

Findings from the current study revealed that different aspects of acculturative stress uniquely impacted Mexican-origin mothers’ adjustment, and that the aspiration–expectation gap may be one mechanism through which acculturative stress shapes young mothers’ adjustment over time. Study findings advance prior research with regard to potential mechanisms by which culturally-related stress is linked with variability in adjustment. Future studies should consider the role of promotive mechanisms, such as coping strategies, as prior work has shown that active behavioral coping mediates the association between acculturative stress and adjustment (i.e., depressive symptomatology; Driscoll & Torres, 2013). These mechanisms are especially important to understand among young Mexican-origin mothers during the early years of parenting and young adulthood, as low educational attainment (Motel & Patten, 2012) and engagement in risky behavior (Assini-Meytin & Green, 2015; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2009) have been linked to negative outcomes for mothers themselves and their offspring (e.g., financial instability, poor parenting; Borkowski et al., 2007). Additionally, a greater understanding of this process may be useful in directing intervention efforts, as greater educational attainment and better behavioral adjustment may facilitate economic stability, social mobility, health-related behaviors, and the developmental outcomes of offspring (Fry, 2010; SmithBattle, 1995).

6.1. Acculturative stress and young Mexican-origin mothers’ aspiration–expectation gap

Importantly, although prior research suggests that teens who enter into early motherhood may be particularly susceptible to experiencing gaps between their educational aspirations and expectations, due to barriers associated with childrearing (e.g., financial and childcare responsibilities; Barr & Simons, 2012; Hoffman, 2006; Leadbeater & Way, 2001), findings from the current study indicated that, on average, the gap between young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational aspirations and expectations was relatively small. In fact, a majority (64%) of young mothers reported educational aspirations that were equivalent to their expectations for themselves, suggesting that study participants reported relatively balanced educational self-concepts regarding their potential for fulfilling their educational endeavors, three years post-partum. This finding may be due, in part, to the time period in which young mothers’ aspirations and expectations were assessed. As noted above, adolescents’ aspiration–expectation gap decreased over time, suggesting that in the years following the transition to motherhood, adolescents’ educational expectations may become more realistic and more closely resemble their aspirations, as these mothers have more experiences negotiating responsibilities as a parent and student. These experiences may help young mothers to focus on attainable educational goals (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002), and thus reduce discrepancies between aspirations and expectations.

Nevertheless, in examining how indicators of acculturative stress were linked to young mothers’ aspiration–expectation gap, we found partial support for our hypotheses, such that mothers were more likely to report a larger gap between their aspirations and expectations when they reported greater stress as a result of English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate. Findings coincide with previous work suggesting that youth who seek to integrate into the host society experience better psychological well-being (i.e., self-esteem), compared to those who prefer minimal involvement in the host culture (Berry & Sabatier, 2010, 2011). Young mothers who experience stress from pressures regarding English language proficiency and involvement in U.S. American culture may be less equipped to adjust in school, as these mothers may have fewer resources to negotiate their educational endeavors (e.g., low rapport with teachers, low self-esteem). Findings contribute to our understanding of how stress resulting from assimilation pressure can be detrimental to the well-being and academic achievement of at-risk ethnic minority groups.

In addition, study findings support notions from possible selves theory, suggesting that individuals are motivated to achieve based on how they perceive their potential and future selves (Nurmi, 2004; Oyserman et al., 2007). English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate may function similarly, in that they may be perceived as barriers that would keep young mothers from fulfilling their aspirations for educational attainment, and thus decrease mothers’ actual expectations for themselves. When young Mexican-origin mothers perceive greater stress resulting from English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate, this may reflect a disconnect with mainstream U.S. culture (Tabors, 1997), making it difficult to expect that they will complete the level of education to which they aspire. Furthermore, increased stress as a result of assimilation and English competency pressures may enhance discrepancies between Mexican-origin mothers’ aspirations and expectations due to perceptions of limited resources (e.g., peer, teacher, institutional support; Yowell, 2002). Findings underscore the need to consider acculturative stress as an important risk factor for groups who struggle with social stigma and devaluation (Berry & Sabatier, 2010, 2011; Rodriguez et al., 2002).

Contrary to our hypotheses, young mothers’ reports of higher levels of stress with regard to pressures against assimilation were associated with a smaller gap between their educational aspirations and expectations. This suggests that stress associated with assimilation pressures served a promotive function toward mothers’ educational self-concept, as a smaller gap between aspirations and expectations has been linked to the completion of educational goals (Oyserman et al., 2007) and positive behavioral adjustment (Boxer et al., 2011). It is possible that stress linked to pressures against assimilation indicate a greater adherence toward the heritage country, or Mexican practices and values. Because research has highlighted the role of education as imperative to life success among Mexican immigrants (Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 1995), young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational self-concept may be similarly positively influenced by pressures that reject the host country practices, and perhaps inadvertently emphasize those from the heritage country.

Interestingly, stress related to Spanish competency pressures did not emerge as a significant predictor of mothers’ aspiration–expectation gap. This null finding suggests that stress resulting from Spanish competency pressures may not function in the same way as stress related to assimilation pressures, with respect to adolescent mothers’ gap between their educational aspirations and expectations. This finding coincides with previous work that suggests that stress associated with pressures against assimilation and Spanish competency pressures, although highly and positively correlated, are distinguishable (Wang, Schwartz, & Zamboanga, 2010). It is possible that stress resulting from Spanish competency pressures may not pose an overt risk for young mothers’ educational self-concept as pressures to retain their heritage language (i.e., Spanish) may not pose a burden on their academic-related adjustment in an English speaking country such as the U.S. Instead, it is possible that Spanish competency pressures may be a relevant stressor for other factors related to the heritage culture (e.g., mental health, family or community support, closeness of relationships; Schwartz et al., 2007; Zhang, Hong, Takeuchi, & Mossakowski, 2012). It will be useful for future work to examine if this finding replicates with other samples.

6.2. The multiple functions of the aspiration–expectation gap

As expected, larger discrepancies between young mothers’ aspirations and expectations were associated with lower levels of educational attainment and greater reports of engagement in risky behaviors. These findings reflect prior work with non-parenting racially and ethnically diverse groups, suggesting that discrepancies between individuals’ aspired and expected levels of educational attainment pose a risk to their subsequent educational attainment and risky behavior engagement (Boxer et al., 2011). A larger aspiration–expectation gap may imply a discouraged academic self-concept, making it difficult to follow through on behaviors that would ensure completion of educational goals (e.g., avoidance of deviant peers and alcohol abuse; Gil et al., 2000). Similarly, a smaller aspiration–expectation gap, indicating that young mothers’ aspired selves are similar to their expected selves, with respect to future educational attainment, may indicate a greater educational self-concept, motivating mothers to engage in strategies that would fulfill their aspired and expected selves (e.g., taking advanced placement courses, attending school; Oyserman et al., 2007).

Because research indicates that young Mexican-origin mothers are at significant risk for educational underachievement (Pew Hispanic Center, 2008) and engagement in risky behavior (e.g., unprotected sex, substance abuse, delinquent behavior; Assini-Meytin & Green, 2015), factors that have been linked with a host of difficulties (e.g., low lifetime earnings, repeat pregnancy, incarnation, developmental delays and health risks for offspring), the current findings have important implications for intervention efforts focused on promoting adjustment for this at-risk understudied population. Specifically, it may be worthwhile to invest in programs focused on increasing young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational expectations, especially toward matching their aspirations during young adulthood, as research has shown that teen mothers typically continue educational pursuits throughout the early years of parenting (Barr & Simons, 2012; Borkowski et al., 2007; Hellenga et al., 2002).

The final goal of the current study was to examine the aspiration–expectation gap as a mediator of the associations between specific indicators of acculturative stress and later educational attainment and engagement in risky behaviors for young Mexican-origin mothers. The aspiration–expectation gap indeed significantly mediated associations between acculturative stress (i.e., English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate) and mothers’ adjustment (i.e., educational attainment and engagement in risky behaviors) two years later. Interestingly, components of acculturative stress were not directly associated with young mothers’ educational and behavioral adjustment, suggesting that the aspiration–expectation gap may be one mechanism through which components of acculturative stress impact young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational attainment and engagement in risky behavior. In line with prior findings highlighting the impact of perceived barriers on discrepancies between youths’ aspirations and expectations (Boxer et al., 2011), perceiving social barriers, such as pressures to assimilate and English competency pressures, may lead to lower educational attainment and increased engagement in risky behavior through mismatched desired and expected levels of educational achievement. This mismatch may demotivate youth from behaving in ways that would ensure the completion of their educational goals (Steele, 1997), such as avoiding engaging with deviant peers, substance abuse, and attending classes. Findings expand on prior work highlighting the direct negative impact of acculturative stress on Latino youths’ educational and behavioral adjustment (Plunkett & Bámaca-Gómez, 2003; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2009), and suggest the aspiration–expectation gap as a potential mechanism through which this process may occur. Further work will be necessary to identify potential protective factors that may buffer the link between acculturative stress and discrepancies between young Mexican-origin mothers’ aspirations and expectations for educational attainment (e.g., teacher or peer support).

Of note, although stress from assimilation pressures was negatively associated with the aspiration–expectation gap, significant mediation between this stressor and study outcomes did not emerge. It is possible that given the small sample size of the current study, there was insufficient power to detect significance. More work with larger samples is needed to further understand the potential protective function of enculturative stressors.

6.3. Limitations and future directions

Although the current study presents important new information regarding an understudied at-risk population, there are some limitations to consider. First, the exclusive use of self-reported, survey data could have introduced shared-reporter and method bias. Future studies should include information from additional reporters (e.g., parents, teachers, peers) to gain a better understanding of young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational and behavioral adjustment. Next, the aspiration–expectation gap was assessed by subtracting two single-item measures. It may be beneficial for future studies to include other indicators of the aspiration–expectation gap, such as strategies employed by youth in connection to their aspired and expected self-concepts (e.g., taking advanced placement courses, engagement in extracurricular activities; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Oyserman et al., 2007).

Regarding the generalizability of findings, although the current study aimed to understand the unique direct and indirect associations between indicators of acculturative stress and young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational and behavioral adjustment, findings may differ for other ethnic minority groups. Indeed, prior work suggests that individuals’ possible selves may vary as a function of their race or ethnicity due to cultural perceptions of expectations and stereotypes, especially among Mexican-origin youth, who are often underestimated for their academic potential (Kao, 2000). Future work should examine the impact of multidimensional indicators of acculturative stress on young adults’ adjustment with other immigrant populations to determine if similar patterns exist, given that Mexican-origin females are less likely to obtain an education compared to other subgroups (i.e., Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Central/South Americans; Frisbie, Forbes, & Hummer, 1998), more likely to engage in risky behaviors (Kann et al., 2014), and may face disparate treatment unique to their ethnic group. Furthermore, future work should account for motherhood at the empirical level by examining whether adolescent motherhood informs the educational aspiration–expectation gap of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. In particular, given that adolescent mothers face unique challenges during pregnancy, and particularly during the transition to motherhood (SmithBattle, 1995), it is possible that motherhood-related factors may make certain aspects of acculturative stress more influential for young mothers’ educational self-concept.

7. Conclusion

Despite the above limitations, the current study contributes to the growing body of literature highlighting the role of acculturative stress on ethnic minority youths’ functioning (Gonzales et al., 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Alfaro, 2009) with an at-risk understudied population. Findings provide an increased understanding of how specific indicators of acculturative stress may uniquely inform the gap between young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational aspirations and expectations, and how this gap, in turn, may inform their educational and behavioral adjustment. Because prior work suggests that gaps between aspirations and expectations have negative behavioral and educational consequences for ethnic minority youth (Boxer et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2000; Oyserman et al., 2007) and teen mothers (Barr & Simons, 2012), it is critical to identify risk, protective, and promotive factors.

The current study highlights the role of acculturative stressors as both risk and promotive factors for young Mexican-origin mothers’ educational self-concept. Specifically, stress related to English competency pressures and pressures to assimilate may have contributed to a negative educational self-concept and thus a larger aspiration–expectation gap; the discrepancy between aspirations and expectations may be a byproduct of internalized social disadvantages, such that when young Mexican-origin mothers experience stressors that may indicate a disconnection from mainstream society or feelings of incompetence (Yowell, 2002), they may have difficulty matching their aspired selves with their expected selves, which ultimately negatively impacts their adjustment during young adulthood. Stress resulting from pressures against assimilation, however, may signify a closer connection with Mexican culture, providing young adults with a sense of community support and an emphasis on education as a critical pathway toward success (Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 1995). These findings highlight the multidimensional role of acculturative stress on young Mexican-origin mothers’ adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant R01HD061376; Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Principal Investigator), the Department of Health and Human Services (Grant APRPA006011; Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Principal Investigator), the Fahs Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation of the New York Community Trust (PI: Umaña-Taylor), and the Cowden Fund and Challenged Child Project of the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. We thank the adolescents and female family members who participated in this study. We also thank Edna Alfaro, Mayra Bámaca, Emily Cansler, Chelsea Derlan, Lluliana Flores, Melinda Gonzales-Backen, Elizabeth Harvey, Melissa Herzog, Sarah Killoren, Ethelyn Lara, Esther Ontiveros, Jacque-line Pflieger, and the undergraduate research assistants of the Supporting Mexican-origin Adolescent Mothers and Infants project for their contributions to the larger study.

References

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Assini-Meytin LC, Green KM. Long-term consequences of adolescent parenthood among African-American urban youth: a propensity score matching approach. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr AB, Simons RL. College aspirations and expectations among new African-American mothers in late adolescence. Gender and Education. 2012;24:745–763. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2012.712097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Caples H, Tein JY. The psychological sense of economic hardship: measurement models, validity, and cross-ethnic equivalence for urban families. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:493–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1010328115110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal SJ, Crockett LJ. Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:258–265. doi: 10.1037/a0017416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Stress perspectives on acculturation. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Sabatier C. Variations in the assessment of acculturation attitudes: their relationships with psychological wellbeing. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35:658–669. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Sabatier C. Acculturation, discrimination, and adaptation among second generation immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2010;34:191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski JG, Whitman TL, Farris JR. Adolescent mothers and their children: risks, resilience, and development. In: Borkowski JG, Farris JR, Whitman TL, Carothers SS, Weed K, Keogh DA, editors. Risk and resilience: adolescent mothers and their children grow up. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Goldstein SE, DeLorenzo T, Savoy S, Mercado I. Educational aspiration–expectation discrepancies: relation to socioeconomic and academic risk-related factors. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo DY, Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, Jahromi LB. Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ educational expectations: predictors and outcomes associated with different growth trajectories. International Journal of Behavioral Development. doi: 10.1177/0165025415616199. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Markus H. Self-schemas, possible selves, and competent performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll MW, Torres L. Acculturative stress and Latino depression: the mediating role of behavioral and cognitive resources. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19:373–382. doi: 10.1037/a0032821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber B. Risky behavior measure. University of Michigan; 1990. Unpublished scale. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Wigfield A. Motivational beliefs, values and goals. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson MG. The meaning of the future: toward a more specific definition of possible selves. Review of General Psychology. 2007;11:348–358. [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Grigsby T, Soto DW, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB. The role of bicultural stress and perceived context of reception in the expression of aggression and rule breaking behaviors among recent-immigrant Hispanic youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30:1807–1827. doi: 10.1177/0886260514549052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbie WP, Forbes D, Hummer RA. Hispanic pregnancy outcomes: additional evidence. Social Science Quarterly. 1998;79:149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. Hispanics, high school dropouts and the GED. Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project. 2010 http://www.pewhispanic.org/2010/05/13/hispanics-high-school-dropouts-and-the-ged/

- Gil AG, Vega WA. Two different worlds: acculturation stress and adaptation among Cuban and Nicaraguan families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13 [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Fabrett FC, Knight GP. Acculturation, enculturation, and the psychosocial adaptation of Latino youth. In: Villarruel FA, Carlo G, Azmitia M, Grau J, Cabrera N, Chahin J, editors. Handbook of US Latino psychology. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BW. Academic disidentification, race, and high school dropouts. High School Journal. 2002;85:71–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hsj.2002.0008. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenga K, Aber MS, Rhodes JE. African American adolescent mothers’ vocational aspiration-expectation gap: individual, social, and environmental influences. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2002;26:200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman S. By the numbers: the public costs of teen childbearing. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kam JA. The effects of language brokering frequency and feelings on Mexican-heritage youth’s mental health and risky behaviors. Journal of Communication. 2011;61:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G. Group images and possible selves among adolescents: linking stereotypes to expectations by race and ethnicity. Sociological Forum. 2000;15:407–430. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk CM, Lewis RK, Scott A, Wren D, Nilsen C, Colvin DQ. Exploring the educational aspirations–expectations gap in eighth grade students: implications for educational interventions and school reform. Educational Studies. 2012;38:507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb S, Markussen E. School dropout and completion: an international perspective. In: Stephen Lamb ao, editor. School dropout and completion: international comparative studies in theory. Netherlands: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJR, Way N. Growing up fast: transitions to early adulthood of inner-city adolescent mothers. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lueck K, Wilson M. Acculturative stress in Latino immigrants: the impact of social, socio-psychological and migration-related factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35:186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lueck K, Wilson M. Acculturative stress in Asian immigrants: the impact of social and linguistic factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2010;34:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellow ZR. Gender variation in developmental trajectories of educational and occupational expectations and attainment from adolescence to adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1069–1080. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena FJ, Padilla AM, Maldonado M. Acculturative stress and specific coping strategies among immigrant and later generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Messersmith EE, Schulenberg JE. When can we expect the unexpected? Predicting educational attainment when it differs from previous expectations. Journal of Social Issues. 2008;64:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Motel S, Patten E. Statistical profile: Hispanics of Mexican origin in the United States, 2010. Pew Research Hispanic Center. 2012 http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/06/27/hispanics-of-mexican-origin-in-the-united-states-2010/

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus Version 6.0 [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Vital Statistics Report. Births: final data for 2012. Division of Vital Statistics. 2013;62:1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi JE. Socialization and self-development: channeling, selection, adjustment, and reflection. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: John Wiley; 2004. pp. 85–124. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Brickman D, Rhodes M. School success, possible selves and parent school-involvement. Family Relations. 2007;56:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Fryberg S. The possible selves of diverse adolescents: content and function across gender, race, and national origin. In: Dunkel C, Kerpelman J, editors. Possible selves: theory, research and applications. New York, NY: Nova; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Perry JC, Przybysz J, Al-Sheikh M. Reconsidering the aspiration-expectation gap and assumed gender differences among urban youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74:349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. Tabulations of the 2008 American Community Survey (ACS) Integrated Public Use Micro Sample (IPUMS) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett WS, Bámaca-Gómez YM. The relationship between parenting, acculturation, and adolescent academics in Mexican-origin immigrant families in Los Angeles. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Roman L, Miranda R. Culturally related stress, hopelessness, and vulnerability to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in emerging adulthood. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JR, Pemberton J. Rising college expectations among youth in the United States: a comparison of the 1979 and 1997 NLSY. The Journal of Human Resources. 2001;36:703–726. [Google Scholar]

- Roche C, Kuperminc GP. Acculturative stress and school belonging among Latino youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012;34:61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, Garcia-Hernandez L. Development of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory for adults of Mexican Origin. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Morris JK, Cardoza D. Latino college student adjustment: does an increased presence offset minority-status and acculturative stresses? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:1523–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW. Dropping out: why students drop out of high school and what can be done about it. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Rodriguez L, Wang SC. The structure of cultural identity in an ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2007;29:159–173. [Google Scholar]