Abstract

Background

Clinical trials testing pharmacogenomic-guided (PG-guided) warfarin dosing for patients with atrial fibrillation(AF) have demonstrated conflicting results. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are expensive and contraindicated for several conditions. A strategy optimizing anticoagulant selection remains an unmet clinical need.

Methods and Results

Characteristics from 14,206 patients with AF were integrated into a validated warfarin clinical trial simulation framework using iterative Bayesian network modeling and a pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic model. Individual dose response for patients was simulated for five warfarin protocols – a fixed-dose protocol, a clinically guided protocol and three increasingly complex PG-guided protocols. For each protocol a complexity score was calculated using the variables predicting warfarin dose and the number of predefined INR thresholds for each adjusted dose. Study outcomes included optimal time in therapeutic range (TTR) ≥65% and clinical events. A combination of age and genotype identified different optimal protocols for various subpopulations. A fixed-dose protocol provided well-controlled INR only in normal responders ≥65, while for normal responders <65 years old, a clinically guided protocol was necessary to achieve well-controlled INR. Sensitive responders ≥65 and <65 and highly sensitive responders ≥65 years old required PG-guided protocols to achieve well-controlled INR. However, highly sensitive responders <65 years old, did not achieve well-controlled INR and had higher associated clinical events rates than other subpopulations.

Conclusions

Under the assumptions of this simulation, patients with AF can be triaged to an optimal warfarin therapy protocol by age and genotype. Clinicians should consider alternative anticoagulation therapy for patients with suboptimal outcomes under any warfarin protocol.

Keywords: anticoagulation, warfarin, pharmacogenetics, comparative effectiveness, simulation

Journal Subject Terms: Atrial Fibrillation, Translational Studies, Genetics, Quality and Outcomes, Ischemic Stroke

INTRODUCTION

Warfarin remains the most commonly prescribed oral anticoagulant for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) despite increasing use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs).1–4 Well-controlled warfarin, as reflected by a minimum time in therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) range (TTR) between 65% and 75%, or NOACs offer optimal anticoagulation outcomes.5–8 Data from two clinical trials demonstrated that 1.58% of patients with well-controlled warfarin (TTR>75%) experienced a major bleeding event, while 3.85% of patients with poorly controlled warfarin (TTR<60%) experienced a major bleeding event.9–10 Compared to NOACs, warfarin offers a more affordable, accessible, and potentially superior option for patients with a history of medication nonadherence.11 However, significant challenges to optimal efficacy and safety outcomes persist with warfarin. Warfarin has a narrow therapeutic window and an up to a 20-fold inter-individual variation in therapeutic dose. As a result, the surrogate outcome most often used in clinical practice, TTR, is often lower than optimal range.7–8 Also, warfarin has been one of the most commonly implicated medications for adverse events leading to emergency department visits and hospital admissions.12 Despite these challenges, warfarin remains a widely used treatment option.

Efforts thus far to optimize therapy have resulted in more than 50 algorithm-guided warfarin therapy protocols of varying complexity. The most complex protocols require as many as 14 independent variables, including demographic, clinical, and genotypic characteristics and suggest up to 7 predefined INR thresholds to predict warfarin dose and manage dose titration (Supplemental material: Table 1A).13–14 Some evidence from clinical trials indicated that pharmacogenomic-guided (PG-guided) dosing algorithms more accurately predicted therapeutic dose, resulting in a revised warfarin label by US FDA (Figure 1).15–20 However, the majority of clinical trials offering algorithm-guided protocols were not powered to assess clinical events in diverse populations.21–24 Furthermore, despite algorithm-guided protocols showing modest increase in TTR from several clinical trials, this increase did not necessarily translate to significant reductions in clinical events.24 Data from recent major clinical trials such as COAG and EU-PACT produced conflicting conclusions regarding the superiority of the fixed-dose standard or clinically guided protocols versus PG-guided protocols to optimize warfarin therapy.23–24 Therefore, optimization of warfarin therapy through clinically guided or PG-guided protocols remains controversial, and continued efforts to optimize warfarin therapy in patients with AF remain warranted.

Figure 1.

FDA’s Warfarin Label: Expected Warfarin Maintenance Doses Based on Genotypes. Ranges are derived from multiple published clinical studies. VKORC1 –1639G>A (rs9923231) variant is used in this table. Other co-inherited VKORC1 variants may also be important determinants of warfarin dose. † Ranges are derived from multiple published clinical studies. VKORC1 –1639G>A (rs9923231) variant is used in this table. Other co-inherited VKORC1 variants may also be important determinants of warfarin dose.

In this study, our objective was to study warfarin therapy optimization with a surrogate end point of TTR, efficacy end point of ischemic stroke, and safety end point of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with newly diagnosed AF. We executed a prospective, five-arm simulated clinical trial incorporating fixed-dose control, clinically guided, and three PG-guided warfarin therapy protocols. To this end, we enhanced the clinical trial simulation framework previously developed and validated by our group, which allows simultaneous comparative effectiveness research by incorporating predicted clinical events, surrogate outcomes such as TTR, and a complexity score associated with each protocol.25 Our study population is derived from the Electronic Medical Records (EMRs) of patients diagnosed with AF and treated within a large hospital network in eastern Wisconsin and northern Illinois. Patient EMRs were then entered into a simulation platform that both simulates the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population and predicts the clinical outcomes from different warfarin therapy protocols. In light of recent PG-guided clinical trials lacking evaluation of both TTR and clinical events in the same study, using a clinical trial simulation framework provides modeled estimates of differences in clinical events between multiple warfarin therapy protocols given the assumptions made in our simulation platform. We hypothesized that more complex warfarin therapy protocols would demonstrate both improved surrogate safety and efficacy outcomes across the entire study population.

METHODS

Our enhanced clinical trial simulation framework consists of the following five scalable components:

Longitudinal EMRs of warfarin-receiving populations to train and validate a Bayesian network model (BNM), which is subsequently used to simulate statistically identical EMRs (thereafter “clinical avatars”).

An empirical and domain knowledge-based method to set study conditions, length of study, number of parallel clinical trials, protocols associated with each clinical trial arm, and the total number of clinical avatars.

A library of warfarin therapy protocols where each protocol comprises an initial, adjustment, and maintenance dosing algorithm.

An automated warfarin therapy simulator, based on a validated pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model, which generates predicted warfarin concentration and INR.26

A clinical outcome calculator that generates treatment outcome metrics (eg, TTR, therapeutic dose of warfarin, efficacy, and safety end points).

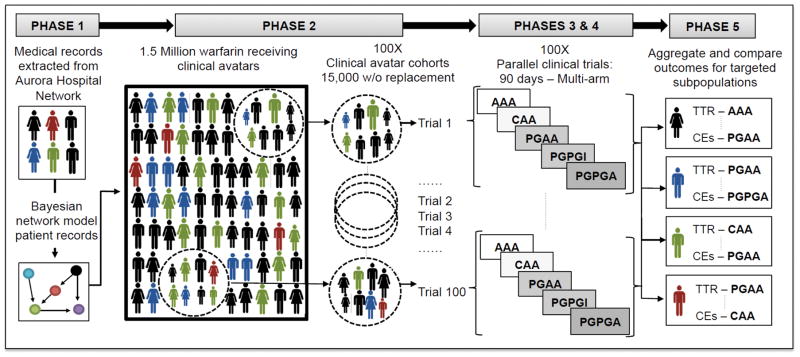

We conducted these five phases throughout the study (Figure 2). Further details of each phase, analytic methods, and study materials are provided in the supplemental material to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Figure 2.

Five-phase study methodology.

Simulated clinical trial arms: AAA, fixed-dose (control) protocol; CAA, clinically guided protocol; PGAA, PG-guided protocol; PGPGI, PG-guided protocol; PGPGA, PG-guided protocol; CEs, clinical events (ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage).

Study design

We designed a five-arm, 90-day clinical trial simulation to test the comparative effectiveness of five warfarin therapy protocols ranging from less to more complex (Table 1). Each of the five protocols are composed of three dosing algorithms that calculate initial warfarin dose, adjustment warfarin dose, and maintenance warfarin dose, which titrate warfarin dose based on INR thresholds. Protocols are described in full in the supplemental materials sections 2.1–2.3.

Table 1.

Dosing Protocols for the Study Arms

| Period | Initial (d) | Adjustment (d) | Maintenance (d) | Normalized Complexity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Arm | ||||

| Fixed-dose (Control) protocol AAA | Aurora (1–2) | Aurora (3–7) | Aurora (8–90) | 1.00 |

| Clinically guided protocol CAA | IWPC Clinical (1–2) | Aurora (3–7) | Aurora (8–90) | 1.38 |

| PG-guided protocol PGAA | IWPC PG (1–2) | Aurora (3–7) | Aurora (8–90) | 1.93 |

| PG-guided protocol PGPGI | Modified IWPC PG (1–3) | Lenzini PG (4–5) | Intermountain (6–90) | 2.50 |

| PG-guided protocol PGPGA | Modified IWPC PG (1–3) | Lenzini PG (4–5) | Aurora (6–90) | 2.56 |

All complexity scores are normalized against the least complex warfarin therapy protocol used in this study, the Aurora best-practice fixed-dose warfarin therapy protocol. D, days; Intermountain, Intermountain Healthcare Chronic Anticoagulation Clinic Protocol; IWPC, International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium.

Protocol Complexity

Current warfarin therapy protocols differ in the number of demographic, clinical, and genetic variables used to personalize warfarin dose and the number of INR-based thresholds used to adjust the dose. Protocol complexity has important implications for patient satisfaction, protocol adherence, cost-effectiveness and potentially clinical outcomes.27–30 We quantified the degree of complexity by counting the number of demographic, clinical, and genetic variables used to personalize warfarin dose and the number of INR-based thresholds used to adjust the dose. The sum of these two counts was aggregated into a “Complexity Score” for each protocol. The score was then normalized against the fixed-dose AAA control protocol (Table 2). Such a measure of complexity facilitates comparison of multiple warfarin therapy protocols and provides an additional metric to interpret parity in clinical outcomes.

Table 2.

Complexity Score

| Dosing Algorithm | Best Practice (Control) Protocol AAA | Clinical Protocol CAA | PG Protocol PGAA | PG Protocol PGPGI | PG Protocol PGPGA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment period | Var. | INR | Var. | INR | Var. | INR | Var. | INR | Var. | INR |

| Initial | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 19 | 2 | 19 | 2 |

| Adjustment | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 2 |

| Maintenance | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| Complexity Score | 16 | 22 | 31 | 40 | 41 | |||||

| Normalized Complexity Score | 1 (16/16) | 1.38 (22/16) | 1.93 (31/16) | 2.50 (40/16) | 2.56 (41/16) | |||||

INR, number of predefined INR-based thresholds for adjusting dose; Var, number of clinical, demographic, or genetic variables used to predict and adjust the warfarin dose.

Study population

We identified and extracted longitudinal EMRs of patients with AF who were taking warfarin at Aurora Health Care (Aurora) over the period of 2002 to 2012. Patient data was de-identified per IRB approval before distribution to the research team. Patient EMR data was then used in a BNM to generate 1,500,000 simulated clinical avatars. The number of clinical avatars was calculated by a power analysis, described in detail in the supplemental materials section 1.2. The 1,500,000 clinical avatars were randomly sampled and distributed over a total of 100 parallel trials. The required number of parallel trials was calculated by a separate power analysis, described in the supplemental materials section 1.2. Each parallel trial was composed of 15,000 clinical avatars, and the same clinical avatar population was tested under each of the five arms of the study. The details of the cohort identification process and data preprocessing are provided in the supplemental material sections 1.1–1.4.

Outcome calculation

The primary outcome metric was TTR with therapeutic INR defined as 2.0 to 3.0 over the first 90 days of simulated treatment, measured by Rosendaal linear interpolation.31 Well-controlled INR was defined as TTR≥65%. Additional thresholds of TTR≥70% and TTR≥75% are evaluated in the supplemental materials.

Secondary outcome metrics included the safety and efficacy events of intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic stroke. The number and incidence rate of intracranial hemorrhagic events were predicted for each subpopulation based on daily INR values of individual clinical avatars.32 We used a similar daily calculation to estimate the number and incidence rate of ischemic strokes.32 The number of events in each arm was rounded to the nearest integer while the incidence rates were reported per 1,000 clinical avatars. The details of event prediction are provided in the supplemental materials section 2.4. Both primary and secondary outcome metrics were then stratified according to the study populations’ clinical characteristics and warfarin responder status as defined by the FDA warfarin label based on the combined profile of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes (Figure 1).20

To facilitate interpretation and dissemination of the results, an interactive results visualization tool was developed in R and has been made publicly available online.33 Both 30-day and 90-day results are available through this tool. The user can interactively select subpopulations of interest for additional analysis of primary and secondary outcomes. The online interactive results visualization tool can be found at https://ari-cds-ar.shinyapps.io/circcvg_paper_app/

Statistical analysis

To validate the BNM against the validation subset of the Aurora EMR data, χ2 analyses were conducted on each discrete variable, and independent t-tests were used on continuous variables. The primary outcome metric of the simulated clinical trials was calculated by finding the mean TTR within a given population in each parallel clinical trial of 15,000 clinical avatars. We then averaged the mean across each arm of 100 parallel trials (ie, mean of means). Standard error of the mean (SEM) was similarly calculated for each parallel clinical trial, and then SEM was calculated for each arm. Results are expressed as mean of means for the primary outcome ± the arm’s SEM unless otherwise specified.

Secondary outcome metrics were reported by summing the number of predicted clinical events within a given population in each parallel clinical trial of 15,000 clinical avatars and then finding the average number of clinical events between 100 parallel trials (ie, mean of sums). All statistical analyses were conducted with R.33 Unless otherwise noted, statistical significance was set at P<.05. Two techniques were used to conduct hypothesis testing across all 100 parallel trials:

We determined the “power” of each comparison by calculating the number of parallel trials where a comparison was demonstrated to be significant divided by the total number of replications (in this case 100). All 100 parallel trials were conducted via a random selection of clinical avatars; therefore, we conducted a one-way, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) over five protocols where the null hypothesis was that all protocols would have the same outcome. This was repeated independently for each of the 100 parallel clinical trials.

We conducted ANOVA for the combined data for all 100 trials via the R package Companion to Applied Regression.34 We used Tukey’s test for pairwise comparison of protocols to measure combined data for all 100 trials. We compared the outcomes, both TTR and clinical event rates, across all five protocols in each subpopulation. A P-value of .05 or less was used as the level of significance for all statistical methods.

RESULTS

We identified Aurora patient EMRs indicating prescription anticoagulation agents, including warfarin, over a 10-year period. The longitudinal dataset included the EMRs of 157,450 patients who were treated with any of ten different anticoagulation agents. Following data cleaning and quality assurance, the resulting data included 14,206 unique patients with AF prescribed warfarin who were then used for BNM training and validation. Bayesian network modeling of the Aurora patient population resulted in a directed acyclic graph ([DAG] see supplemental material: Figure 1A) and associated conditional probability tables (CPTs). Univariate and bivariate variable analysis demonstrated no significant difference between the model and the validation data. As described by the power analysis (Supplemental materials section 1.2.), we estimated 15,000 clinical avatars were necessary for each of the 100 parallel clinical trials. Subsequently, we generated 1,500,000 clinical avatars from the trained and validated BNM.

The study population’s characteristics had no statistically significant differences (P<.05) between the Aurora warfarin population and the clinical avatar population for both continuous and discrete variables (Table 3).35 The clinical avatar populations had an average age of 67.2±14.47 with 53.10% female and 46.90% male. Racial characteristics included 95.22% white, 4.19% African-American and less than 1% Asian, American Indian/Alaskan, or Pacific Islander. Stratifying the avatar population according to responder status, based on combination of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 used on the FDA warfarin label (Figure 1), demonstrates 61% normal responders, 35% sensitive responders, and 4% highly sensitive responders.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Original Aurora AF Warfarin and Aurora Clinical Avatar Populations

| Characteristic | Aurora AF Warfarin Population (mean±SD) | Aurora Clinical Avatar Population (mean±SD) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, year, | 67.3±14.43 | 67.2±14.47 |

|

| ||

| Weight, lb, | 199.24±54.71 | 199.24±54.6 |

|

| ||

| Height, in, | 66.78±4.31 | 66.53±4.32 |

|

| ||

| Gender, % | ||

| Female | 53.14 | 53.10 |

| Male | 46.86 | 46.90 |

|

| ||

| Race, % | ||

| White | 95.18 | 95.22 |

| African-American | 4.25 | 4.19 |

| Asian | 0.39 | 0.40 |

| Am. Indian/Alaskan | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Pacific Islander | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Tobacco, % | ||

| No | 90.33 | 90.67 |

| Yes | 9.66 | 9.33 |

|

| ||

| Amiodarone, % | ||

| No | 88.45 | 88.49 |

| Yes | 11.54 | 11.51 |

|

| ||

| Fluvastatin, % | ||

| No | 99.97 | 99.98 |

| Yes | 0.03 | 0.02 |

|

| ||

| CYP2C9, % | ||

| *1/*1 | 65.77* | 67.39 |

| *1/*2 | 14.6* | 14.86 |

| *1/*3 | 9.11* | 9.25 |

| *2/*2 | 6.41* | 6.51 |

| *2/*3 | 1.93* | 1.97 |

| *3/*3 | 0* | 0 |

|

| ||

| VKORC1, % | ||

| G/G | 38.54* | 38.37 |

| G/A | 44.02* | 44.18 |

| A/A | 17.33* | 17.45 |

Aurora patient population’s genotypic characteristics were derived from published genotype distributions.35

Primary outcome metric

Across the whole population, the TTR of the control arm was 57.2%±0.17 (Table 4). Compared to the control arm, increasingly complex treatment protocols demonstrated significantly higher TTR (P<.05). Only the moderately complex protocol, PGAA, demonstrated well-controlled INR (TTR≥65%) with TTR of 77.4%±0.14. In addition, results by different TTR thresholds for well-controlled INR, 70% and 75%, are also provided in the supplemental material (Tables 1A and 2A).

Table 4.

90-day TTR Across Five Study Arms

| Protocol

|

AAA (Control) | CAA | PGAA | PGPGI | PGPGA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subpopulations | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Responder status | Age | N | TTR (SEM) | ||||

| Whole population | 15,000 | 57.2 (0.17) | 69.8‡ (0.14) | 77.4§ (0.14) | 63.0‡ (0.14) | 67.4‡ (0.10) | |

|

| |||||||

| Normal responder | ≥65 | 5328 | 81.6 (0.17) | 78.8 (0.17) | 83.7§ (0.17) | 68.5 (0.17) | 70.7 (0.10) |

|

| |||||||

| Normal responder | <65 | 3882 | 53.4 (0.22) | 80.0‡ (0.17) | 80.4§ (0.20) | 67.1‡ (0.20) | 71.3‡ (0.14) |

| Sensitive responder | ≥65 | 3023 | 50.2 (0.22) | 62.7‡ (0.24) | 74.3§ (0.22) | 58.9‡ (0.22) | 64§ (0.17) |

|

| |||||||

| Sensitive responder | <65 | 2211 | 25.9 (0.20) | 52.5‡ (0.24) | 65.8§ (0.22) | 54.7§ (0.22) | 62.5§ (0.20) |

| Highly sensitive responder | ≥65 | 345 | 16.9 (0.30) | 25.1‡ (0.37) | 66.7§ (0.40) | 39.8§ (0.39) | 48.9§ (0.35) |

|

| |||||||

| Highly sensitive responder | <65 | 253 | 12.9 (0.28) | 18.9‡ (0.35) | 54.6§ (0.46) | 36.1§ (0.44) | 47.4§ (0.39) |

Subpopulations grouped by age and genotype. We tested differences in TTR across all five protocols in each subpopulation and all are statistically significant (P<.05) via ANOVA on the combined data from 100 parallel clinical trials. N, number of clinical avatars; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Indicates outcomes superior to the control protocol, AAA.

Indicates outcomes superior to the clinical guided protocol, CAA.

Subpopulations defined by genotype, as defined by responder status (Figure 1), and age (<65 years old) demonstrated significantly different TTRs in each of the five arms (Table 4).

The largest subpopulation, normal responders, ≥65 years (35%), had significantly higher TTR in all protocols than in the whole population. All protocols achieved well-controlled INR, including the least complex control protocol with a TTR of 81.6%. In contrast, normal responders <65 years old (26%) did not achieve well-controlled INR in the control protocol with a TTR of 53.4%. However, the clinically guided CAA protocol as well as the PG-guided PGAA, PGPGI, and PGPGA protocols all demonstrated well-controlled INR. The CAA protocol was the least complex protocol of the three and produced a TTR of 80.0%.

A smaller subpopulation of sensitive responders, ≥65 years old (20%), required PG-guided dosing to achieve well-controlled INR. This population had TTR lower than the whole population in all protocols. Only the moderately complex PG-guided protocol, PGAA, had well-controlled INR with a TTR of 74.3%. Similarly, sensitive responders <65 years old (15%) and highly sensitive responders ≥65 years old (2%) achieved well-controlled INR only in the PGAA protocol with TTR of 65.8% and 66.7%, respectively, which was significantly higher than the control arm TTR. However, Highly sensitive responders <65 years old (2%) had very poor INR control in the control arm and clinically guided protocol with TTR of 12.9% and 18.9%, respectively. In this subpopulation, despite significantly improved TTR in the PG-guided protocols, the other complex protocols failed to reach TTR ≥65%.

Secondary outcome metrics

Comparing any personalized warfarin therapy protocol to the control protocol, there was a significant reduction in both the number of ischemic strokes and intracranial hemorrhagic events in the whole population and within some, but not all, subpopulations stratified by age and genotype. Increasing the complexity of warfarin therapy protocols had a greater impact in reducing the number of intracranial hemorrhages compared to the reduction in ischemic strokes (see supplemental material: Tables 3A and 4A).

The number of intracranial hemorrhagic events and the average incidence rate dropped most in PG-guided protocols compared to the control arm. PGPGA had the lowest number of intracranial hemorrhages with 78 and an incidence rate of 5.2 (P<.05) over 90 days. Ischemic stroke events were also lowest in the PG-guided protocols compared to the less complex clinically guided or control protocol. The number of stroke events fell to 26, for a rate of slightly less than 2 in both the PGPGI and PGPGA arms (Table 5).

Table 5.

Average Number and Incidence Rate of Clinical Events Across the Entire Study Population over the 100 Parallel Trials

| Protocol | AAA (Control) | CAA | PGAA | PGPGI | PGPGA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Number* | Rate† | Number* | Rate† | Number* | Rate† | Number* | Rate† | Number* | Rate† |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 104 | 6.9 | 87‡ | 5.8 | 80§ | 5.3 | 81§ | 5.4 | 78§ | 5.2 |

| Ischemic stroke | 33 | 2.2 | 31‡ | 2.1 | 29§ | 1.9 | 26§ | 1.7 | 26§ | 1.7 |

| Combined events | 137 | 9.1 | 118‡ | 7.9 | 109§ | 7.2 | 107§ | 7.1 | 104§ | 6.9 |

All comparisons in this table are statistically significant (P<.05) when tested across unrounded incidence rates of clinical events on the combined data. SEMs were not included since the numbers of events were rounded to the nearest integer.

Number of events: number of clinical events in the first 90 days.

Rate: incidence rate of the clinical events per 1,000 avatars rounded to the nearest tenth.

Indicates outcomes superior to the control protocol, AAA.

Indicates outcomes superior to the clinical guided protocol, CAA.

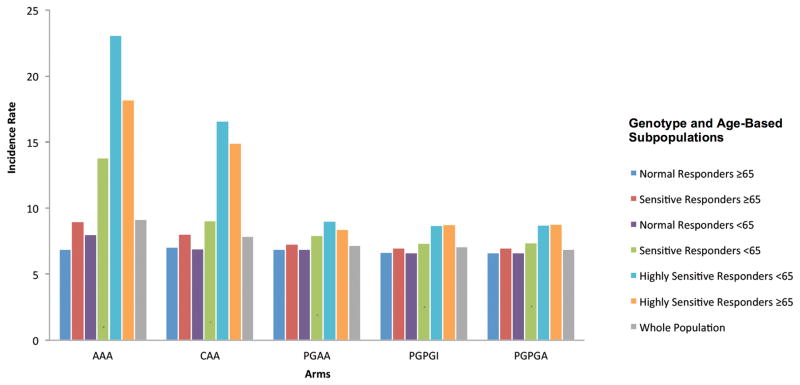

Subpopulations stratified by age and genotype demonstrated significantly different incidence rates of intracranial hemorrhages and ischemic strokes over 90 days. Normal responders, ≥65 years old, had a similar number of events and incidence of events in all protocols regardless of protocol complexity (Figure 3). Normal responders <65 years old saw a reduction in clinical events in more complex protocols compared to the control protocol. The most complex PG-guided protocols, PGPGI and PGPGA, saw the lowest combined number of ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage events (Table 5). However, this was only marginally improved compared to the clinically guided CAA protocol over 90 days (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Combined incidence rate of ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage events across subpopulations defined by age and genotype. Incidence rate defined as an event per 1,000 avatars over 90 days. The complexity of the warfarin therapy protocols increase from left (the least complex protocol AAA), to right (the most complex protocol PGPGA).

Similarly, sensitive responders ≥65 years old, also saw the greatest reduction in clinical events in the PG-guided protocols compared to the control protocol. Highly sensitive responders of any age, and sensitive responders <65 years old had the greatest reduction of combined intracranial hemorrhages and ischemic strokes in the PG-guided protocols (Figure 3). The greatest reduction in ischemic stroke was seen in the PGPGI and the PGPGA compared to the control arm. Highly sensitive responders <65 years old fell from a maximum of nine ischemic strokes per 1,000 clinical avatars in the control arm to two in the PGPGI arm and two in the PGPGA arm over 90 days (P<.05) (Supplemental material: Table 3A).

Expanded results can be viewed through an interactive online viewer at https://ari-cds-ar.shinyapps.io/circcvg_paper_app/

DISCUSSION

In this 90-day, five-arm simulated warfarin therapy clinical trial, clinically guided or PG-guided protocols significantly improved primary and secondary outcomes across the whole study population when compared to the least complex control protocol. Furthermore, subpopulations stratified by age and genotype demonstrated significant differences in outcome according to protocol complexity.

In other studies, both responder status and age have been independently shown to predict TTR and risk of clinical events.36–38 Based on simulation results, including both TTR and clinical events, matching subpopulations defined by genotype and age with the least complex warfarin therapy protocols could produce optimal outcomes. Providing patients and clinicians with the least complex warfarin therapy possible would improve the medical errors associated with medication administration and usage and decrease the practical challenges involved in implementing complex therapy protocols in every day clinical settings.27–30 Furthermore, providing patients with the least complex possible warfarin therapy, including once daily prescriptions and no cut pills can increase protocol adherence, increase TTR and improve patient satisfaction.28

Using a simulation approach to personalize anticoagulation therapy offers several advantages and similar techniques have been used previously to calculate the cost effectiveness of different anticoagulation therapies.39 The simulation platform used in this study provides possible outcomes, including a clinical event calculation that can be applied across multiple warfarin therapy protocols for small subpopulations at a fraction of the time and expense of large clinical trials. In addition, because this approach uses clinical avatars, results can be made publicly available while maintaining HIPAA compliance. Furthermore, using clinical avatars allows for the same avatar to be tested across multiple protocols mitigating the counterfactual problem of clinical trials in the setting of simulation. The results generated through this simulation approach can be used to refine individual protocols for specific subpopulations. The refined protocols can then be simultaneously evaluated across the entire population to determine the most advantageous clinical trial design.

Normal responders ≥65 years old, representing 35% of the total study population, had both well-controlled INR and low rates of clinical events in the least complex control arm (Table 6).

Table 6.

Optimal Warfarin Therapy Protocols by Age and Genotype for a Well-controlled INR with TTR Threshold of 65%

| Protocol (Complexity Score) | <65 Years Old | ≥65 Years Old | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Responder (26%) | Sensitive Responder (15%) | Highly Sensitive Responder (2%) | Normal Responder (35%) | Sensitive Responder(20%) | Highly Sensitive Responder (2%) | |

| AAA (1) | - | - | - | O-LC | - | - |

| CAA (1.38) | O-LC | - | - | O | - | - |

| PGAA (1.93) | O | O-LC | - | O | O-LC | O-LC |

| PGPGI (2.50) | O | - | - | O | - | - |

| PGPGA (2.56) | O | - | - | O | - | - |

| Recommendation for anticoagulant other than warfarin | - | - | √ | - | - | - |

The therapy protocols that would result in optimal outcomes are marked by “O”. The least complex protocols are marked by “O-LC”.

However, normal responders <65 years old, representing 26% of the study population, demonstrated well-controlled INR and low clinical event rates only under the clinically guided or PG-guided protocols. Optimizing for the least complex protocol would suggest that the clinically guided protocol is best for these patient populations. Similar to prior studies, our results show that younger age has been associated with lower TTR under some protocols.32 Our results suggest that the AAA, CAA, and PGAA protocols do not appropriately account for the increase in warfarin metabolism for younger patients with AF with respect to either initial dose or dose adjustment (days 3–7). The PGPGI and PGPGA protocols, which have more frequent dose adjustment (days 3–7), show similar TTR for patients of all ages. This would suggest younger patients with AF should have closer INR monitoring and dose adjustment, particularly in the first week of therapy after initiating warfarin.

Sensitive and highly sensitive responder patients, accounting for the remaining 39%, derived the greatest benefits from PG-guided warfarin therapy. Within the control arm, these patients demonstrated a significantly higher rate of clinical events compared to normal responders; consistent with a recently reported clinical trial.36 We observed no clinical benefit from increasing complexity beyond the moderately complex PG-guided protocol for these populations. This PG-guided protocol, with PG-guidance for the initial dose alone, demonstrated the highest TTR across the entire population and all subpopulations. Similarly, this arm also had significantly lower rates of ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhagic events compared to the clinically guided and control arms. The benefits of PG-guided warfarin therapy are consistent with several additional recent studies suggesting that PG-guided warfarin dosing is associated with fewer clinical events.21–23, 37 The most complex PG-guided protocols used in arms 4 and 5, which included PG-guidance for initial dose and adjustment period, Days 3 through 7, demonstrated significantly inferior TTR compared to either the least complex PG-guided arm or the clinically guided arm. These results are consistent with the outcomes from recent warfarin therapy clinical trials comparing PG-guided versus standard best practice and clinically guided dosing.23–24 For patients initiating warfarin therapy, it is important that providers administering warfarin have evidence to support the use of more or less complex warfarin therapy when appropriate.

Sensitive responders <65 years of age and highly sensitive responders ≥65 years old, 17% of the population, marginally achieved well-controlled INR only in the PGAA protocol according to a TTR threshold of 65%. This would suggest that either the PGAA protocol or NOACs might be the preferred anticoagulation therapy for these patients depending on patient and provider’s preference. A direct comparison between the PGAA protocol and NOACs would provide additional clarity on the optimal strategy. For highly sensitive responders <65 years old (2%) who did not achieve well-controlled INR and had higher associated clinical events rates compared to other subpopulations in any warfarin protocol, NOACs might be the only preferred anticoagulation therapy option.

Highly sensitive responders, in particular, are rare and account for less than 4% of our study population. But within our framework, they are large enough to conduct statistical analysis. Recent PG-guided dosing clinical trials did not report results for these small subpopulations and their rarity in the general population could account for the differing clinical trials’ results.23–24 Fluctuating the minimum threshold of well-controlled INR between 65% and 75% affects the suggested optimal anticoagulation therapy for ~39% of the study population, including sensitive and highly sensitive responders (Table 6, Supplemental material: Tables 1A and 2A). A direct comparative effectiveness study powered for appropriate subgroup analysis with these patients is necessary and appropriate to determine if NOACs are particularly beneficial for these patients.

These results suggest that age (< or ≥65 years) and combination of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genotype can be used to determine optimal anticoagulation therapy. Patients initiating warfarin therapy could be triaged to the optimal least complex warfarin therapy protocol, or potentially NOACs, using the combination of age and genotype. The possibility of identifying patients who would optimally benefit from more complex PG-guided dosing or NOAC therapy has important cost-saving and clinical outcome implications.

Limitations

This study is based on a clinical outcome calculation model using a combination of patient EMR data and subsequent mathematical modeling. As such, there are necessary simplifications within the model and it is potentially limited in its ability to account for all covariates and confounders of warfarin therapy. For example, outcomes for patients with certain rare CYP2C9 variants were excluded. These patients account for about 1.5% of the US warfarin receiving population and were not included in the PK/PD simulation, including *4 and *5 variants noted to be more prevalent in the African-American population. The simulated clinical trial framework was validated against results from the CoumaGen clinical trial and therefore does not predict how warfarin therapy is executed in daily clinical practice.25 Although INR prediction has been previously validated in a simulation setting, the clinical outcome calculation derived from daily INR values has not been validated in a simulation setting. Furthermore, clinical event prediction is predicated using daily INR values versus all potential variables related to clinical events in the real world. Therefore the distribution of predicted clinical events between protocols and subpopulations is more pertinent than the absolute rate. Minor improvements in clinical outcomes demonstrate statistical significance because of the large study population and the number of parallel simulated clinical trials. However, statistical significance in the setting of large simulation does not necessarily confer robust evaluation of the null hypothesis. Treatment effects determined to be statistically significant may be too small to confer clinical relevance because of the large study population and number of parallel trials. Simulation results should thus be interpreted with caution and emphasis placed on outcome distribution between subpopulations and arms.

Conclusions

In a five-arm, 90-day simulated clinical trial, more complex warfarin therapy protocols did not universally improve TTR or reduce clinical events. Subpopulations defined by age (<65 years old) and genotype information (combined variants of CYP2C9 and VKORC1) demonstrate significantly different outcomes from including clinical and genotype information in the warfarin therapy protocol. When considering warfarin therapy for newly diagnosed AF, triaging the patient by age and genotype information could optimize the choice of anticoagulation treatment. A prospective study investigating the surrogate outcome, TTR, as well as clinical events, could be considered to validate these results.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

The goal of Precision Medicine Initiative launched in 2015 was to transition medicine from a “one-size-fits-all-approach” to one that accounts for the individual differences in people’s genes, environments, and lifestyles. Despite these efforts, the clinical trial framework for translating scientific evidence to the bedside remains largely unchanged. In this article, we suggest a new approach to enhance clinical trial design utilizing electronic health records combined with computer simulation. This new method implies the creation of a “virtual sandbox” where clinicians and investigators can compare various clinical outcomes across diverse patient populations to support the most efficient and effective clinical trial design. This study applies the simulation approach to evaluate the thorny issue of anticoagulation therapy with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. The simulated clinical trial in this study demonstrates that just knowing the age and genotype of a patient optimizes selection of the appropriate anticoagulation regime and should be favored over a “one-size-fits-all-approach.” An additional advantage of simulation is that resultant data can be made public. We therefore introduce readers to the idea of “living-papers” with an embedded online tool that readers can interact with to navigate the study results by selecting subpopulations or dosing regimens of interest. Although simulation will not replace real world clinical trials in the foreseeable future, it could help design better clinical trials, bringing us faster towards the bold initiative of Precision Medicine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Maharaj Singh, principal biostatistician at Aurora Research Institute, for his scientific and statistical advice. We also thank Andrew Marek for assistance in identifying, collecting, and warehousing the EMR data used in this study. We would also like to thank Marcus Walz for his technical support and Sandra Kear for editing. Finally, we thank Dr. Michael Michalkiewicz for his significant efforts to approve and facilitate the use of Aurora’s EMR data for this study and for scientific advice.

SOURCES OF FUNDING: NIH Grant: 1R01LM011566-01

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: None

References

- 1.Pilote L, Eisenberg MJ, Essebag V, Tu JV, Humphries KH, Leung Yinko SS, et al. Temporal trends in medication use and outcomes in atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Sylwestrzak G, Barron J, Rosenberg A, White J, Whitney J, et al. Evaluation of practice patterns in the treatment of atrial fibrillation among the commercially insured. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1707–1713. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.922061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basaran O, Filiz Basaran N, Cekic EG, Altun I, Dogan V, Mert GO, et al. PRescriptiOn PattERns of Oral Anticoagulants in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation (PROPER study) Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2017;23:384–391. doi: 10.1177/1076029615614395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huisman MV, Rothman KJ, Paquette M, Teutsch C, Diener HC, Dubner SJ, et al. Antithrombotic Treatment Patterns in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: The GLORIA-AF Registry, Phase II. Am J Med. 2015;128:1306–1313. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trusler M. Well-managed warfarin is superior to NOACs. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:23–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Bachmann F, et al. Vitamin K antagonists in heart disease: current status and perspectives (Section III). Position paper of the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis--Task Force on Anticoagulants in Heart Disease. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:1087–1107. doi: 10.1160/TH13-06-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harper P, McMichael I, Griffiths D, Harper J, Hill C. The community pharmacy-based anticoagulation management service achieves a consistently high standard of anticoagulant care. N Z Med J. 2015;128:31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melamed OC, Horowitz G, Elhayany A, Vinker S. Quality of anticoagulation control among patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J of Manag Care. 2011;17:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson SB. Stroke prevention with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF III): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1691–1698. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akins PT, Feldman HA, Zoble RG, Newman D, Spitzer SG, Diener HC, et al. Secondary stroke prevention with ximelagatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: pooled analysis of SPORTIF III and V clinical trials. Stroke. 2007;38:874–880. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258004.64840.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer KA. Pros and cons of new oral anticoagulants. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:464–470. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, Gage BF, Kimmel SE, Lee MT, et al. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:753–764. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenzini P, Wadelius M, Kimmel S, Anderson JL, Jorgensen AL, Pirmohamed M, et al. Integration of genetic, clinical, and INR data to refine warfarin dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:572–578. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodin L, Verstuyft C, Tregouet DA, Robert A, Dubert L, Funck-Brentano C, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) and vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKORC1) genotypes as determinants of acenocoumarol sensitivity. Blood. 2005;106:135–140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geisen C, Watzka M, Sittinger K, Steffens M, Daugela L, Seifried E, et al. VKORC1 haplotypes and their impact on the inter-individual and inter-ethnical variability of oral anticoagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:773–779. doi: 10.1160/TH05-04-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sconce EA, Khan TI, Wynne HA, Avery P, Monkhouse L, King BP, et al. The impact of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic polymorphism and patient characteristics upon warfarin dose requirements: proposal for a new dosing regimen. Blood. 2005;106:2329–2333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadelius M, Pirmohamed M. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin: current status and future challenges. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:99–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y, Shennan M, Reynolds KK, Johnson NA, Herrnberger MR, Valdes R, Jr, et al. Estimation of warfarin maintenance dose based on VKORC1 (-1639 G>A) and CYP2C9 genotypes. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1199–1205. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coumadin[package insert] Bristol Myers Squibb; New York, NY: Sep, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson JL, Horne BD, Stevens SM, Grove AS, Barton S, Nicholas ZP, et al. Randomized trial of genotype-guided versus standard warfarin dosing in patients initiating oral anticoagulation. Circulation. 2007;116:2563–2570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JL, Horne BD, Stevens SM, Woller SC, Samuelson KM, Mansfield JW, et al. A randomized and clinical effectiveness trial comparing two pharmacogenetic algorithms and standard care for individualizing warfarin dosing (CoumaGen-II) Circulation. 2012;125:1997–2005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pirmohamed M, Burnside G, Eriksson N, Jorgensen AL, Toh CH, Nicholson T, et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2294–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimmel SE, French B, Kasner SE, Johnson JA, Anderson JL, Gage BF, et al. A pharmacogenetic versus a clinical algorithm for warfarin dosing. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2283–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fusaro VA, Patil P, Chi CL, Contant CF, Tonellato PJ. A systems approach to designing effective clinical trials using simulations. Circulation. 2013;127:517–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.123034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamberg AK, Dahl ML, Barban M, Scordo MG, Wadelius M, Pengo V, et al. A PK-PD model for predicting the impact of age, CYP2C9, and VKORC1 genotype on individualization of warfarin therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:529–538. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruess DG, O’Leary K, Platt AB, Kimmel SE. Improving patient adherence to warfarin therapy. JCOM. 2010;17:505–509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hixson-Wallace JA, Dotson JB, Blakey SA. Effect of regimen complexity on patient satisfaction and compliance with warfarin therapy. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2001;7:33–37. doi: 10.1177/107602960100700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muroi M, Shen JJ, Angosta A. Association of medication errors with drug classifications, clinical units, and consequence of errors: Are they related? Appl Nurs Res. 2017;33:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Metwali B, Mulla H. Personalised dosing of medicines for children. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;69:514–524. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amouyel P, Mismetti P, Langkilde LK, Jasso-Mosqueda G, Nelander K, Lamarque H. INR variability in atrial fibrillation: a risk model for cerebrovascular events. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.An {R} Companion to Applied Regression [computer program] Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott SA, Khasawneh R, Peter I, Kornreich R, Desnick RJ. Combined CYP2C9, VKORC1 and CYP4F2 frequencies among racial and ethnic groups. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:781–791. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mega JL, Walker JR, Ruff CT, Vandell AG, Nordio F, Deenadayalu N, Murphy SA, Lee J, Mercuri MF, Giugliano RP, Antman EM, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Genetics and the clinical response to warfarin and edoxaban: findings from the randomised, double-blind ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2280–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61994-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhoef TI, Ragia G, de Boer A, Barallon R, Kolovou G, Kolovou V, et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2304–2312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apostolakis S, Sullivan RM, Olshansky B, Lip GY. Factors affecting quality of anticoagulation control among patients with atrial fibrillation on warfarin: the SAMe-TT2R2 score. Chest. 2013;144:1555–1563. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pink J, Pirmohamed M, Lane S, Hughes DA. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin therapy vs. alternative anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;95:199–207. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.