Abstract

Although the percentage of crimes committed by females has increased over the last 20 years in the United States, most research focuses on crimes by males. This article describes an examination of the extent to which childhood maltreatment predicts violent and nonviolent offending in females and the role of psychiatric disorders. Using data from a prospective cohort design study, girls with substantiated cases of physical and sexual abuse and neglect were matched with nonmaltreated girls (controls) on the basis of age, race, and approximate family socioeconomic class, and followed into adulthood (N = 582). Information was obtained from official arrest records and participant responses to a standardized structured psychiatric interview. Women with a history of any childhood maltreatment, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect were at significantly increased risk for having an arrest for violence, compared to control women. Except for those with a history of physical abuse, abused and neglected women were also at increased risk for arrest for a nonviolent crime, compared to controls. In bivariate chi-square comparisons, the three groups of women (violent offenders, nonviolent offenders, and nonoffenders) differed significantly in the diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and dysthymia, but not major depressive disorder, and violent female offenders had significantly higher rates of these disorders compared to nonoffenders. However, with controls for age and race, PTSD was the only psychiatric disorder to distinguish women arrested for a violent crime compared to a nonviolent crime (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 6.32, confidence interval [95% CI] = 1.84–21.68, p < 0.01), and PTSD moderated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and violent offending (AOR = 5.55, 95% CI = 1.49–20.71): women with histories of childhood maltreatment were equally likely to have an arrest for violence, regardless of PTSD diagnosis, whereas having a diagnosis of PTSD increased the risk of violence for women without maltreatment histories. Together, these findings suggest two pathways to violent offending among females—one through childhood maltreatment and a second through PTSD. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: : female offenders, violence, childhood abuse and neglect, psychiatric disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder

Introduction

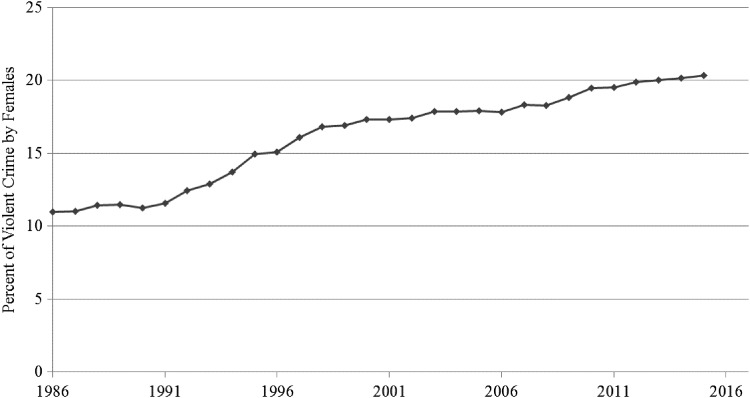

Most research on violent crime has focused on males. Although the number of violent crimes in the United States has been decreasing, the percentage of violent crimes committed by women has increased (FBI Criminal Justice Information Services Division 2015; see Fig. 1). Much has been written about female crime specifically (Belknap and Holsinger 2006; Burgess-Proctor 2006; Kruttschnitt 2016), and general theories of crime have been adapted to explain female-perpetrated crimes (Broidy and Agnew 1997; Koon-Magnin et al. 2016; Piquero and Sealock 2004). Nonetheless, better understanding of the causes and correlates of female offending, and specifically, violent female offending is needed.

FIG. 1.

Line graph showing the percentage of violent crime committed by females from 1986 to 2015 based on Uniform Crime Report Publications of FBI Crime Statistics 1995–2015.

In this article, we focus on the role of childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorders as potential risk factors for violence by women (e.g., Chen and Gueta 2015; Innocenti et al. 2014; Muller and Kempes 2016; Pollock et al. 2006; Salisbury and Van Voorhis 2009).

Self-reports from incarcerated women reveal a high prevalence of past trauma, with 47% of a sample of women in U.S. jails reporting childhood sexual abuse and 40% reporting childhood physical abuse (Lynch et al. 2012). Prospective longitudinal studies have also demonstrated a connection between childhood maltreatment and female crime (Maxfield and Widom 1996; Widom 1989a), and female violent crime, more specifically (Herrera and McCloskey 2003; Lansford et al. 2007). Some studies have drawn particular attention to the relationship between a history of sexual abuse and female violence (Herrera and McCloskey 2003; Siegel and Williams 2003).

Other literature has focused on the extent to which female violence is associated with psychiatric disorders, primarily posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, and personality disorders (e.g., Kendra et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2017). In their meta-analysis of the prevalence of mental disorders in nonviolent and violent prisoners in Western nations, Fazel and Danesh (2002) included nearly 3000 women and found that 12% met criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD), 4% for psychosis, and 42% for any personality disorder (21% with antisocial personality disorder). Female violent and nonviolent incarcerated offenders have also been reported to have a higher prevalence of alcohol and drug abuse compared to females in the general population (Brunelle et al. 2009; Dixon et al. 2004).

Although the existing body of research suggests that child maltreatment and psychopathology play a role in female violent offending, there are a number of limitations that detract from our ability to draw firm conclusions. First, the majority of studies have been cross-sectional, relying heavily on retrospective self-reports of childhood victimization (Browne et al. 1999; Harlow 1999; Lynch et al. 2012; McClellan et al. 1997; Pflugradt et al. 2017; Zlotnick 1997), which is potentially problematic because of problems with forgetting, reconstruction of memory, and inconsistencies in reports over time (Brewin et al. 1993; Henry et al. 1994; Offer et al. 2000; Schraedley et al. 2002). Second, many studies (e.g., Ogloff et al. 2012; Papalia et al. 2017; Siegel and Williams, 2003; Trabold et al. 2015) have focused on only one type of abuse (sexual), rather than multiple types. Third, many studies lack comparison or control groups, which are important to understand differences between offenders and nonoffenders (Arboleda-Florez et al. 1998; Walsh et al. 2002). Fourth, some studies have compared violent to nonviolent female offenders (e.g., Stephenson et al. 2014); however, violent and nonviolent offending have more often been studied separately (e.g., Varley Thornton et al. 2010).Finally, existing studies have focused on women in prison; the reliance on incarcerated samples may be problematic because some of the observed mental illness may be due to the experience of incarceration. To overcome some of these limitations, this study uses a prospective cohort design with documented cases of child maltreatment and matched control girls to investigate the extent to which childhood abuse and neglect predict violent offending in women and the extent to which psychiatric disorders play a role in violent and nonviolent offending.

Hypotheses

(1) Females with documented histories of child abuse and/or neglect will be more likely to have arrests and arrests for violent crimes, compared to matched controls.

(2) Female violent offenders will have higher rates of psychiatric disorders than female nonviolent offenders and both groups of female offenders (violent and nonviolent) will have higher rates of psychiatric disorders compared to female nonoffenders. In particular, violent female offenders will have higher rates of mood disorders (MDD and dysthymia), PTSD, and alcohol and drug abuse compared with nonviolent offenders.

(3) Childhood maltreatment will interact with these psychiatric disorders (particularly PTSD) to increase a woman's risk of violent offending.

Materials and Methods

Design and participants

Data were collected as part of a large prospective cohort design study in which abused and/or neglected children were matched with nonabused and non-neglected children and followed into adulthood (Widom 1989b). The original sample of abused and neglected children was made up of all substantiated cases of childhood physical and sexual abuse and neglect processed from 1967 to 1971 in the county juvenile (family) or adult criminal courts of a Midwestern metropolitan area. Cases of abuse and neglect were restricted to children 11 years of age or less at the time of the incident. Children without documented histories of childhood abuse and/or neglect (controls) were matched with the abuse/neglect group on age, sex, race/ethnicity, and approximate family social class. This matching was important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse and neglect and subsequent outcomes is confounded with or explained by social class differences (MacMillan et al. 2001; Widom 1989b).

The initial phase of the study compared the abused and/or neglected children to the matched comparison group (total N = 1575) on juvenile and adult criminal arrest records (Widom 1989a). A second phase involved locating and interviewing the abused and/or neglected and comparison groups during 1989–1995 (N = 1196). Although there was attrition associated with death, refusals, and the inability to locate individuals over the various waves of the study, the demographic composition of the sample has remained about the same.

This study includes 582 females with mean age 29.63 (range 18.95–40.71, SD = 3.86) at the time of the first interview in the years 1989–1995. About 59.5% of participants self-identified as White, non-Hispanic and 40.5% identified as Black, Hispanic, or Asian. Previous work has shown that this sample includes a heavy predominance of children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Widom 1989a). Overall, more than a third (35.57%) of these women met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III-Revised (DSM-III-R: American Psychiatric Association 1987) criteria for PTSD, 28.69% for MDD, 14.78% dysthymia, 39.18% alcohol abuse, and 26.29% drug abuse.

Procedures

Interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study and the inclusion of an abuse/neglect group. Participants were also blind to the purpose of the study and were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in that area during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for these procedures, and participants provided written, informed consent. For individuals with limited reading ability, the consent form was explained verbally.

Measures

Childhood maltreatment

Childhood physical and sexual abuse and neglect were assessed through review of official records processed during the years 1967 to 1971. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, and bone and skull fractures. Sexual abuse cases included fondling or touching, felony sexual assault, sodomy, incest, and rape. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents' deficiencies in child care were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time and represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children. Of the 582 women, 44.16% had documented cases of neglect, 8.08% of physical abuse, and 13.06% of sexual abuse. The total number of these specific types of abuse and neglect adds up to more than 388 because some participants experienced more than one type of abuse or neglect.

Offender status

Offender status is based on information from criminal arrest histories collected at multiple levels of law enforcement at three points in time (1986–1987, 1994, and 2013–2014). Juvenile and adult arrests for nonviolent and violent crimes were included through mean age 51.33 (SD = 3.56, range = 42–61) at the most recent criminal history search. Violent crimes include arrests for the following crimes and attempts: assault, battery, robbery, manslaughter, murder, rape, and burglary with injury. Participants were labeled violent offenders if they had a history of an arrest for any violent crime (N = 63). The nonviolent offender group (N = 149) consisted of individuals who had arrests for nontraffic and nonviolent offenses (e.g., theft, prostitution, and drugs). Nonoffenders (N = 370) had no documented arrests.

Psychiatric disorders

The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule–III (revised) (DIS-III-R: Robins et al. 1989), a structured interview, was used to determine psychiatric diagnoses based on the DSM-III-R criteria (American Psychiatric Association 1987). We report lifetime prevalence, that is, the proportion of the group who ever met the criteria for each disorder. Psychiatric disorders include MDD, dysthymia, alcohol and drug abuse and/or dependence, and PTSD. Diagnoses of MDD require the presence of five symptoms from nine categories, including depressed mood, diminished interest in activities, lost appetite, insomnia, psychomotor retardation, fatigue, worthlessness, diminished ability to concentrate, and thoughts of death. Dysthymia refers to a pattern of depressive symptoms that has persisted for most of the day, more days than not, for at least 2 years and includes difficulties in eating and sleeping, low self-esteem, fatigue, poor concentration, and hopelessness. Alcohol and drug abuse and/or dependence disorders were defined as the presence of three of nine symptoms, including taking large quantities of the substance, interference with functioning, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms. PTSD is characterized by a group of symptoms in response to a trauma that includes reexperiencing (e.g., intrusive thoughts, dreams, and flashbacks), avoidance of stimuli related to a traumatic event, changes in arousal and reactivity, and mood symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regressions were conducted with SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL) to assess differences in the likelihood of violent and nonviolent offending for the abused and neglected women and controls, and for specific types of abuse (physical and sexual) and neglect. Chi-square tests were performed to provide percentages of psychiatric diagnoses both for descriptive purposes and to compare groups without controlling for other factors. The Compare column proportions option, which computes pairwise comparisons of column proportions and indicates which pairs of columns (for a given row) in the cross-tabulation table are significantly different from one another, was used. Because our outcome variable was dichotomous, binary logistic regressions were performed to determine whether child maltreatment and psychiatric disorders predicted violent and nonviolent offending. We report adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with controls for age and race (White vs. non-White), to provide an estimate of the effect size (Hayes and Matthes 2009). Because we are using logistic regression, we report Nagelkerke's Pseudo R-square to indicate the extent of explained variance.

Results

Does child abuse and neglect predict violent and nonviolent offending?

Table 1 shows that women with documented histories of childhood maltreatment were at an increased risk of having an arrest for violent and nonviolent crimes, compared to matched control women. AORs ranged from 2.72 to 3.73 for a violent crime and 1.84 to 2.23 for a nonviolent crime. Each type of childhood maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect) significantly increased risk for an arrest for violence for these women, and all but physical abuse significantly increased risk for a nonviolent arrest. Overall, 33.43% of these women with documented histories of child abuse and neglect had an arrest for a nonviolent crime and 13.91% had an arrest for violence, compared to 22.92% and 6.56%, respectively, for the controls.

Table 1.

Predicting Violent and Nonviolent Offending among Females with Histories of Childhood Abuse and Neglect and Matched Controls

| Arrest for a violent crime | Arrest for a nonviolent crime | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N | N (%) | AOR | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 | N (%) | AOR | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 | |

| Control | 244 | 16 (6.56) | 56 (22.95) | ||||||

| Child abuse and neglect | 338 | 47 (13.91) | 3.00** | [1.61–5.57] | 0.12 | 113 (33.43) | 1.99*** | 1.35–2.92 | 0.04 |

| Physical abuse | 47 | 8 (17.02) | 3.73** | [1.41–9.84] | 0.07 | 15 (31.91) | 1.94 | 0.95–3.99 | 0.02 |

| Sexual abuse | 76 | 10 (13.16) | 2.72* | [1.12–6.62] | 0.08 | 24 (31.56) | 1.84* | 1.02–3.33 | 0.02 |

| Neglect | 257 | 35 (13.62) | 3.08** | [1.60–5.93] | 0.13 | 92 (35.80) | 2.23*** | 1.48–3.35 | 0.06 |

p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio with controls for age and race; CI, confidence interval; Pseudo R2, Nagelkerke pseudo R-square reflects the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model.

Lifetime psychiatric disorders and offending in maltreated females and controls

Table 2 shows the extent to which the three groups of women met the criteria for the psychiatric diagnoses examined in this study and presents the results of chi-square analyses. The three groups of women (violent offenders, nonviolent offenders, and nonoffenders) differed significantly in the extent of PTSD, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and dysthymia, but not MDD. Pairwise comparisons of column proportions revealed that violent offenders had significantly higher rates of PTSD and dysthymia compared to both nonviolent offenders and nonoffenders, and that offenders (violent and nonviolent) had significantly higher rates of alcohol and drug diagnoses than did nonoffenders, without controls for demographic characteristics.

Table 2.

Descriptive Bivariate Statistics on the Extent of DSM-III-R Lifetime Psychiatric Disorders in Violent and Nonviolent Female Offenders and Nonoffenders (in Percent)

| Psychiatric diagnosis | Violent offenders (N = 63) | Nonviolent offenders (N = 169) | Nonoffenders (N = 350) | Chi square |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 51.61a | 35.50b | 32.86b | 8.08* |

| Alcohol abuse and/or dependence | 50.79a | 47.93a | 32.86b | 14.87** |

| MDD | 39.68 | 26.63 | 27.71 | 4.24 |

| Drug abuse and/or dependence | 38.10a | 31.36a | 21.84b | 10.31** |

| Dysthymia | 25.40a | 13.61b | 13.43b | 6.33* |

Subscript letters represent pairwise comparisons of column proportions for a given row. When two groups have different letters (a, b), they are significantly different (p < 0.05) from one another on that characteristic.

p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III-Revised; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Table 3 presents the results of logistic regression analyses predicting offender type based on psychiatric disorder diagnoses, with controls for age and race. Violent female offenders differed from nonoffenders across all psychiatric disorders, whereas nonviolent offenders differed from nonoffenders only in terms of drug abuse/dependence diagnosis. Violent and nonviolent offenders differed only in the extent of PTSD diagnoses, and individuals with PTSD were approximately six times more likely to be arrested for a violent compared to a nonviolent crime.

Table 3.

Logistic Regressions Predicting Violent and Nonviolent Female Offending and Interaction of Childhood Abuse and Neglect and Psychiatric Diagnoses

| Violent vs. nonoffenders | Violent vs. nonviolent offenders | Nonviolent vs. nonoffenders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 | AOR | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 | AOR | 95% CI | Pseudo R2 | |

| CAN | 3.00** | [1.61–5.57] | 0.12 | 1.43 | [0.74–2.77] | 0.05 | 1.99*** | [1.35–2.92] | 0.04 |

| PTSD | 7.61*** | [2.45–23.62] | 0.17 | 6.32** | [1.84–21.68] | 0.11 | 1.32 | [0.67–2.62] | 0.05 |

| CAN × PTSD | 5.55* | [1.49–20.71] | 4.28* | [1.04–17.66] | 1.42 | [0.61–3.27] | |||

| Alcohol | 3.01* | [1.04–8.72] | 0.16 | 2.36 | [0.74–7.50] | 0.06 | 1.31 | [0.68–2.52] | 0.08 |

| CAN × Alcohol | 1.21 | [0.35–4.23] | 2.11 | [0.55–8.04] | 0.50 | [0.23–1.13] | |||

| MDD | 3.46* | [1.20–10.03] | 0.15 | 3.00 | [0.93–9.63] | 0.08 | 1.26 | [0.63–2.52] | 0.05 |

| CAN × MDD | 2.46 | [0.69–8.77] | 1.66 | [0.42–6.61] | 1.58 | [0.66–3.78] | |||

| Drug | 4.15* | [1.39–12.37] | 0.16 | 1.88 | [0.59–6.03] | 0.06 | 2.57** | [1.29–5.12] | 0.07 |

| CAN × Drug | 2.31 | [0.63–8.46] | 1.26 | [0.32–4.95] | 1.89 | [0.80–4.49] | |||

| DYS | 5.66** | [1.67–19.15] | 0.15 | 3.53 | [0.93–13.43] | 0.08 | 1.88 | [0.75–4.76] | 0.05 |

| CAN × DYS | 3.69 | [0.86–15.86] | 1.93 | [0.39–9.63] | 2.75 | [0.88–8.62] | |||

p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Alcohol, alcohol abuse and/or dependence disorder; CAN, childhood abuse and neglect; drug, drug abuse and/or dependence disorder; DYS, dysthymia; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Does childhood maltreatment interact with these psychiatric disorders (particularly PTSD) to increase a woman's risk of violent offending?

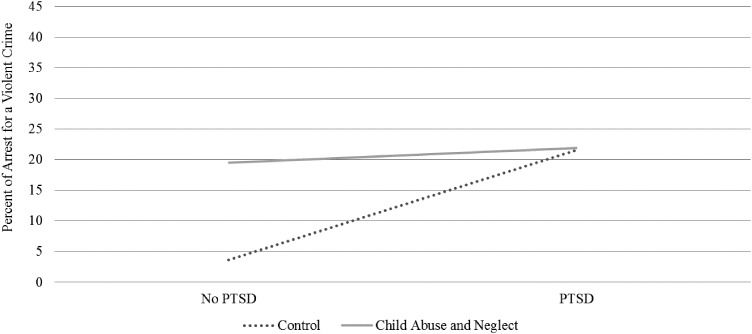

The final hypothesis was that childhood maltreatment would interact with these psychiatric disorders (particularly PTSD) to increase a woman's risk of violent offending. Table 3 shows that PTSD was the only psychiatric disorder that moderated risk for an arrest for violence. However, we did not find support for our hypothesis, but rather the results show the opposite. Figure 2 illustrates this interaction and shows that women with a history of childhood maltreatment were equally likely to become violent offenders, regardless of PTSD diagnosis [χ2(1, 224) = 0.19, p > 0.05]. However, for women with no documented history of childhood maltreatment, having a PTSD diagnosis significantly increased their risk for arrest for a violent crime compared to those without a PTSD diagnosis [χ2(1, 188) = 15.33, p < 0.001].

FIG. 2.

Significant interaction between childhood maltreatment and PTSD diagnosis predicting an arrest for a violent crime (compared to no arrest) (adjusted odds ratio = 5.55, 95% confidence interval = 1.49–20.71, p < 0.05). PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Women with a history of childhood maltreatment were equally likely to become violent offenders compared to nonviolent offenders, regardless of PTSD diagnosis [χ2(1, 158) = 0.61, p > 0.05]. However, for women with no documented history of childhood maltreatment, having a PTSD diagnosis significantly increased their risk for arrest for a violent crime compared to those without a PTSD diagnosis [χ2(1, 71) = 8.57, p < 0.01].

We conducted post hoc analyses to examine the temporal sequence between age of onset of PTSD diagnosis and age of first violent arrest. Thirty-two women in this sample met criteria for PTSD and had at least one violent arrest. Of those women, for 84.38%, the age of onset for PTSD was earlier than the age of first violent arrest, whereas for 15.63%, the age of first violent arrest was earlier than their age at PTSD diagnosis. For those women who had a PTSD diagnosis first, their average age of PTSD diagnosis was 18.07 (SD = 5.62, range = 9–28) and average age of first violent arrest was 31.21 (SD = 8.46, range 15–45). For those who had a violent arrest first, the average age of first violent arrest was 16.34 (range = 14–18.80, SD = 1.86) and their average age of PTSD diagnosis was 21.20 (range = 17–25, SD = 3.56).

Discussion

Using data from a prospective cohort design study, these results show that girls who have documented histories of child abuse and neglect are at a significantly increased risk for being arrested for violent and nonviolent offenses. At the same time, it is important to note that this risk is not deterministic, since almost half the women with a history of maltreatment did not have any arrest. Nonetheless, these findings should reinforce efforts to intervene early in the lives of abused and neglected girls to decrease their risk for future crime and violence.

Compared to national statistics using the same instrument (Robins and Regier 1991), the women in this sample in general had high rates of psychiatric disorders. This is not surprising given the extensive literature documenting the deleterious mental health consequences of child maltreatment (e.g., Gilbert et al. 2009), and that about half of the women in this sample have documented histories of child abuse and/or neglect. However, these results indicate that violent and nonviolent offenders have even higher rates than abused and neglected women without arrest histories.

While our results revealed high rates of psychiatric disorders in these female offenders (violent and nonviolent), PTSD was the only psychiatric diagnosis that distinguished between violent and nonviolent offending in these women. We also found that having a PTSD diagnosis moderated the relationship between child maltreatment and violent offending, suggesting an important role for PTSD in violent offending (Widom 2014). Women with histories of child abuse and neglect were about equally likely to have an arrest for violence, regardless of whether they had a diagnosis of PTSD or not. In contrast, women with no documented history of childhood maltreatment and no PTSD diagnosis were unlikely to be arrested for a violent crime, whereas these women (controls) who had PTSD were at a substantially increased risk and almost as likely to become violent as women with histories of childhood maltreatment.

These new findings suggest that there may be two paths to violence for women—the first as a consequence of child abuse and neglect and the second in conjunction with traumas associated with PTSD. Efforts to intervene in women with PTSD should recognize the potential for violence and provide resources for survivors of trauma to address symptoms before violence occurs. At the same time, it is noteworthy that 53% of the violent crimes were committed by women who did not have PTSD, suggesting that other factors play a role in violence by women.

Our finding that PTSD preceded the violent offending more often than following the violence is worthy of comment. One possible explanation is that women who develop PTSD may become more hypervigilant, and therefore, more likely to react physically in situations that they perceive to be unsafe. A second possibility is that these women may have been in abusive relationships, develop PTSD as a consequence (Widom 2014), and then physically attack their abuser. Future research should examine these possibilities and pathways to violent offending in females. However, these findings reinforce current efforts directed at women with PTSD and those in violent relationships to provide preventive interventions early on—before the violence occurs. Future research in this area should also be expanded to examine the relationships among race, ethnicity, childhood maltreatment, psychiatric disorders, and other potential predictors of violent female offending.

The nonviolent female offenders in this sample did not differ from nonoffenders in terms of PTSD, MDD, or dysthymia, although they were at a significantly increased risk for drug use and dependence diagnoses. Further research is necessary to understand the circumstances of the arrests for these nonviolent female offenders. For example, are they engaging in crimes to feed expensive drug habits? Or is it that their substance abuse problems are leading them to make poor choices in life? This study has begun to attempt to disentangle the roles of childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorders in understanding different types of offending among women, but raises many questions for scholars to pursue in the future.

Despite notable strengths of this study, some caveats should be noted. First, the data used in this study are based on diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders that were established in the late 1980s. Due to changes in the DSM since that time, this study may not have captured all of the PTSD in the sample. A second limitation is that it is unknown whether the control group may have also experienced child abuse or neglect that went unreported. The interaction of child abuse and neglect and PTSD predicting risk for violent offending may reflect a limitation of relying exclusively on official reports of child maltreatment. There is increasing evidence that self-reported victimization experiences have negative health and mental health consequences (e.g., Coles et al. 2015; Font and Maguire-Jack 2016). However, the fact that significant differences were found between the abused/neglected group and the controls on multiple measures suggests that these differences exist, even if conservatively examined in this sample. Third, this sample contains a heavy predominance of women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; so these results may not be generalizable to children whose abuse or neglect occurred in the context of more affluent families. While this study controlled for race, future research should look further at the relationship between race and ethnicity, childhood maltreatment, psychiatric disorders, and female offending, keeping in mind how differences in policing may lead to differences in arrest rates.

Conclusions

Both childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorders play a significant role in violent and nonviolent offending in females. Despite previous literature highlighting the role of childhood sexual abuse in female violence, these results indicate that other forms of childhood abuse (physical) and neglect place girls at risk for subsequent violent offending. These new findings also reveal the important role of PTSD in female violent offending and that PTSD appears to be a risk factor for female violence, rather than an outcome. With the increase in the percentage of violent crimes committed by females, future research focused on these and other factors related to female offending is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by grants from NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033, 89-IJ-CX-0007, and 2011-WG-BX-0013), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edition, revised). (American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC: ). [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda-Florez J, Holley H, Crisanti A. (1998). Understanding causal paths between mental illness and violence. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol. 33, S38–S46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J, Holsinger K. (2006). The gendered nature of risk factors for delinquency. Fem Criminol. 1, 48–71 [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH. (1993). Psychopathology and early experience: A reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychol Bull. 113, 82–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy L, Agnew R. (1997). Gender and crime: A general strain theory perspective. J Res Crime Delinq. 34, 275–306 [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Miller B, Maguin E. (1999). Prevalence and severity of lifetime physical and sexual victimization among incarcerated women. Int J Law Psychiatry. 22, 301–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle C, Douglas RL, Pihl RO, et al. (2009). Personality and substance use disorders in female offenders: A matched controlled study. Pers Indiv Differ. 46, 472–476 [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Proctor A. (2006). Intersections of race, class, gender, and crime: Future directions for feminist criminology. Fem Criminol. 1, 27–47 [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Gueta K. (2015) Child abuse, drug addiction, and mental health problems of incarcerated women in Israel. Int J Law Psychiatry. 39, 36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles J, Lee A, Taft A, et al. (2015). Childhood sexual abuse and its association with adult physical and mental health: Results from a national cohort of young Australian women. J Interpers Viol. 30, 1929–1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon A, Howie P, Starling J. (2004). Psychopathology in female juvenile offenders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 45, 1150–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Danesh J. (2002). Serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners: A systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet. 359, 545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FBI Criminal Justice Information Services Division. (2015). Crime in the United States 2013. Uniform Crime Reports. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2015/crime-in-the-u.s.-2015/tables/table-33 (accessed November10, 2017)

- Font SA, Maguire-Jack K. (2016). Pathways from childhood abuse and other adversities to adult health risks: The role of adult socioeconomic conditions. Child Abuse Negl. 51, 390–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garyfallos G, Adarnopoulou A, Karastergiou , et al. (1999). Personality disorders in dysthymia and major depression. Acta Psychiat Scand. 99, 332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, et al. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 373, 68–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow CW. (1999). Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers. (U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC: ) NCJ. 172879, 1–4 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav Res Methods. 41, 924–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. (1994). On the “remembrance of things past”: A longitudinal evaluation of the retrospective method. Psychol Assess. 6, 92–101 [Google Scholar]

- Herrera VM, McCloskey LA. (2003). Sexual abuse, family violence, and female delinquency; Findings from a longitudinal study. Violence Vict. 18, 319–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti A, Hassing LB, Lindqvist AS, et al. (2014). First report from the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register (SNFPR). Int J Law Psychiatry. 37, 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendra R, Bell KM, Guimond JM. (2012). The impact of child abuse history, PTSD symptoms, and anger arousal on dating violence perpetration among college women. J Fam Viol. 27, 165–175 [Google Scholar]

- Koon-Magnin S, Bowers D, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, et al. (2016). Social learning, self-control, gender, and variety of violent delinquency. Deviant Behav. 37, 824–836 [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C. (2016). The politics, and place, of gender in research on crime. Criminology. 54, 8–29 [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, et al. (2007). Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreat. 12, 233–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM, DeHart DD, Belknap J, et al. (2012). Women's Pathways to Jail: The Roles and Intersections of Serious Mental Illness & Trauma. (Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC: ). [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, et al. (2001). Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 158, 1878–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. (1996). The cycle of violence: Revisited 6 years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 150, 390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan DS, Farabee D, Crouch BM. (1997). Early victimization, drug use, and criminality a comparison of male and female prisoners. Crim Justice Behav. 24, 455–476 [Google Scholar]

- Muller E. Kempes M. (2016). Gender differences in a Dutch forensic sample of severe violent offenders. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 15, 164–173 [Google Scholar]

- Offer D, Kaiz M, Howard KI, et al. (2000) The altering of reported experiences. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 39, 735–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogloff JR, Cutajar MC, Mann E, et al. (2012). Child sexual abuse and subsequent offending and victimisation: A 45 year follow-up study. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, Issue 440 (June 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Papalia NL, Luebbers S, Ogloff JR, et al. (2017). Exploring the longitudinal offending pathways of child sexual abuse victims: A preliminary analysis using latent variable modeling. Child Abuse Negl. 66, 84–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugradt DM, Allen BP, Zintsmaster AJ. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences of violent female offenders: A comparison of homicide and sexual perpetrators. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 1–7. (online) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero NL, Sealock MD. (2004). Gender and general strain theory: A preliminary test of Broidy and Agnew's gender/GST hypotheses. Justice Q. 21, 125–158 [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JM, Mullings JL, Crouch BM. (2006). Violent women findings from the Texas Women Inmates study. J Interpers Violence. 21, 485–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, et al. (1989). National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III Revised (DIS-III-R). (Washington University, St. Louis, MO.) [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Regier DA, eds. (1991). Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. (Free Press, New York, NY: ) [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury EJ, Van Voorhis P. (2009). Gendered pathways: A quantitative investigation of women probationers' paths to incarceration. Crim Justice Behav. 36, 541–566 [Google Scholar]

- Schraedley PK, Turner RJ, Gotlib IH. (2002). Stability of retrospective reports in depression: Traumatic events, past depressive episodes, and parental psychopathology. J Health Soc Behav. 43, 307–316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JA, Williams LM. (2003). The relationship between child sexual abuse and female delinquency and crime: A prospective study. J Res Crime Delinq. 40, 71–94 [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson Z, Woodhams J, Cooke C. (2014). Sex differences in predictors of violent and non‐violent juvenile offending. Aggress Behav. 40, 165–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabold N, Swogger MT, Walsh Z, Cerulli C. (2015). Childhood sexual abuse and the perpetration of violence: The moderating role of gender. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 24, 381–399 [Google Scholar]

- Varley Thornton AJ, Graham-Kevan N, Archer J. (2010). Adaptive and maladaptive personality traits as predictors of violent and nonviolent offending behavior in men and women. Aggress Behav. 36, 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh E, Buchanan A, Fahy T. (2002). Violence and schizophrenia: Examining the evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 180, 490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li C, Zhu XM, et al. (2017). Association between schizophrenia and violence among Chinese female offenders. Sci Rep. 7, 818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. (1989a). Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 59, 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. (1989b). The cycle of violence. Science. 244, 160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. (2014). Varieties of violent behavior. Criminology.52, 313–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), PTSD comorbidity, and childhood abuse among incarcerated women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 185, 761–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]